France

Populism is by no means a new phenomenon in France; rather it is almost as old as the fifth republic itself. However, post-2010 has seen a rise in populism thanks to the European debt crisis, waves of immigration, and the terror attacks of 2015 and 2016. As a savvy populist who attentively touches sore spots, Marine Le Pen capitalizes on immediate issues and concerns in the country, such as immigration, the EU, and terrorism, while avoiding fruitless debates such as same-sex marriage and abortion. Feeding on the widespread angst about the so-called dissolution of French identity and the French way-of-life, the National Rally today offers a France that is out of the Schengen area and that completely ends immigration, whether legal or not.

Located in Western Europe, France is a unitary semi-presidential republic and one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council as well as a key member in the European Union and NATO. With the Revolution of 1789, France emerged as a hotbed of nationalism and democratic ideals that generated a powerful populist current as anti-elite sentiments played a key role in mobilizing common people against the monarchy. Since the revolution, the territories which today fall within the borders of modern France have experienced ten different governmental systems, including the renowned Napoleonic empire and the five hectic periods of republican governments. Under the fifth and the current Republic, established by Charles de Gaulle in 1958, France ended its colonization of Algeria, which led to a deep-seated resentment among the evacuated settlers and nationalists and continues to nurture fascist elements in French politics.

Given its long experience of republican governments, populism is by no means a new phenomenon in France. The current form of populism dates to the mid-1950s, when an anti-tax and anti-modernization organization, the Poujadist Movement, managed to send a total of 52 deputies to the National Assembly after gathering some 11 percent of the vote in the 1956 elections (Riding, 2003). Though not well-organized (the Movement quickly fell apart in 1958), the Poujadists helped their leader, Pierre Poujade, to put his stamp on history as the “grandfather of populism” in France (Connolly, 2016). During the 1960s, right-wing populism began to assert greater influence in the country with occasional outbursts in relation to the war in Algeria. In the 1965 presidential election, ex-Poujadist and far-right politician Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour received 5.2 percent of the vote; his campaign slogan was “militant of all the nationalist parties whichever they may be” (Shields, 2007).

Established in 1972, the National Front (FN – now the National Rally, RN) has turned into France’s leading populist party by taking a clamorous anti-liberal stance and advancing radical right ideas. The then-party leader, Jean-Marie Le Pen, a French nationalist and a former supporter of the fascist Vichy regime which collaborated with Nazi Germany during World War II, capitalized on the frustration over de Gaulle’s decision to withdraw from Algeria. Since making its first serious debut in mayoral elections in Paris and Dreux in the early 1980s, the RN has developed into a catch-all party for French populists and far-right ideologues and a role model for other populist organizations around the world. In the 1986 French legislative elections, the party managed to garner almost 10 percent of the vote and 35 seats, while in the 1995 presidential election, Jean-Marie Le Pen, won over 15 percent of the vote. By the late 1990s, it became clear that the RN was a significant force in French politics. In 2002, Le Pen unexpectedly appeared in the second round of the presidential election.

The RN has been ascendant in the post-2010 period as France grappled with the European debt crisis, waves of immigration, and the terror attacks of 2015 and 2016. As a classic far-right populist party with a special emphasis on French nationalism, anti-immigrant and anti-Islam sentiments and an extreme opposition to France’s membership in the European Union, the Eurozone, and NATO, the party has nearly won national elections (Davies, 2012).

The RN is widely associated with Jean-Marie Le Pen and his daughter, Marine Le Pen, who has served as the party’s leader since 2011. The heavy and pricy burden of populism has therefore been carried by this father-daughter duo’s charismatic leadership. Both have proved willing to bypass democratic institutions and attack the free press – and have suggested they would become autocrats if the circumstances allowed. Throughout his career as the leader of his party, Father Le Pen often made the headlines with his hate speech against Jews, Muslims, and many other minority groups. In 2016, he was convicted by a French court for stating that “the gas chambers used to kill Jews in the Holocaust were only detail of history” (Chrisafis, 2016).

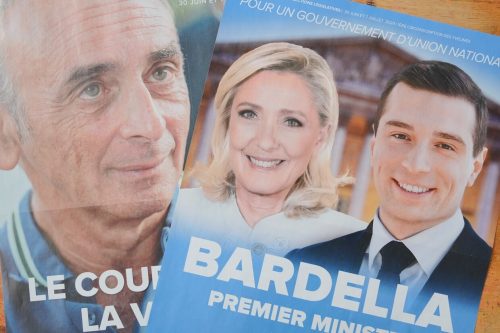

The sensational career of “Devil of the Republic” came to a dramatic end when Marine Le Pen assumed the party’s leadership from her father in January 2011 (NEWS.com.au, 2011). In that year’s election, daughter Le Pen managed to secure third place in the presidential election with 17.90% of the vote. In 2017, she advanced to the second and final round of voting in the presidential election. Although Emmanuel Macron of En Marche won by a decisive margin, Le Pen received approximately 34% of the vote, a clear sign that the populist backlash in Europe is real and pervasive. Throughout her election campaign, she employed a purely populist strategy, such as pushing against immigrants, globalization, Islam, and the European Union, while her rival advocated for further integration with Europe, more globalization, and pluralist society. In the run-up to the 2017 election, US President Donald Trump expressed his support for Le Pen in an interview with the Associated Press, saying that he believed she was the “strongest on borders, and she’s the strongest on what’s been going on in France” (Quigley, 2017).

In 2018, members of the then National Front voted to change the party’s name to the “National Rally” in an attempt to appeal to a broader range of voters and to hide the party’s past association with antisemitism. However, the RN’s position on other key issues has not changed at all: Le Pen wants to take France out of the Schengen area, deport irregular immigrants, and completely end immigration, whether legal or not. Feeding on the widespread angst about the so-called dissolution of French identity and the French way-of-life, she has vowed to end the “mad, uncontrolled situation” by mobilizing thousands to protect the country’s borders from a flux of refugees: “Mass immigration is not an opportunity for France, it’s a tragedy. […] With me, there wouldn’t have been the migrant terrorists of the Bataclan and the Stade de France” (Dearden, 2017). Le Pen also believes that France is under an imminent threat from economic globalization and Islamic fundamentalism (Nossiter, 2017). If someday elected, she promises to strip dual-citizen Muslims of French nationality and deport all that are found unfit. However, it should be noted that the RN does not have a monopoly on Islamophobia; rather it is a phenomenon that unites many French political figures, from far left to far right.

Often translated as “Unsubmissive France,” La France Insoumise (LFI) is another populist party that is worth noting. Founded in early 2016 by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, LFI is largely inspired by Spain’s Podemos and the USA’s Democratic Socialists, led by Bernie Sanders. The party is a left-wing anti-establishment party that has built a discourse around “the people against the oligarchy.” The party’s leader surprised in the 2017 presidential election by receiving almost 20 percent of the first-round votes. In the same year, LFI secured 17 seats in the 2017 legislative election, enough to form a group in the National Assembly. As of 2020, however, many argue that the party is increasingly losing its appeal as its base shrinks to that of a traditional far-left party (Banbara, 2019).

In terms of civil liberties, France is a free country. French people enjoy a vibrant democratic system with regular and competitive multiparty elections, while a fair record of civil liberties and political rights is retained. There are currently six (6) populist political parties in France, led by the National Rally.[1] With its unique combination of nationalism, opposition to immigration (especially from Muslim countries), and strong anti-establishment sentiments, the RN’s fame has gone beyond national boundaries. The party today enjoys very close ties with many like-minded political actors around the world, such as the Austrian Freedom Party, the UK Independence Party, the Sweden Democrats, the Belgian Flanders, Germany’s Citizens in Rage, the Slovak National Party, and the Tea Party movement in the United States.

Needless to say, the liberal centrist Macron’s victory in the 2017 presidential elections did not end the hopes of France’s right-wing populists; rather, it strengthened their resolve to achieve more in the near future. Indeed, the RN made its debut in the 2019 European Parliament by winning some 23 percent of the national vote. The reason behind this success was that as a savvy populist, Le Pen continues to press all the “right” buttons, focusing on controversial issues such as immigration, the EU, and terrorism, while avoiding fruitless, potentially hazardous debates such as same-sex marriage and abortion.

The National Rally’s anti-establishment features also increasingly appeal to working-class voters in the country’s industrial north, which has suffered from the recent economic downturn and the decline of traditional industries. Arguments that predict the dissolution of far-right populism in France are therefore doubtful. Although it is still a long way off, Ms. Le Pen’s desire to be “Madame Présidente,” is not just a fanciful dream, as it was for father Le Pen. Such a right-wing populist presidency and Frexit may come as a package deal, which the European project would certainly not survive.

June 15, 2020

References

— (2015). “National Front leader Marine Le Pen tipped for French Presidential run following terror attacks,” NEWS.com.au, January 23, 2015. https://www.news.com.au/finance/work/leaders/national-front-leader-marine-le-pen-tipped-for-french-presidential-run-following-terror-attacks/news-story/e772a1f86fa2e8e322bfa25ebe9c0fdc

Banbara, Lenny. (2019). “Comment la France insoumise est devenue un parti de gauche contestataire,” Le Vent se Lève, September 25, 2019. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/09/france-insoumise-lfi-jean-luc-melenchon-macron

Chrisafis, Angelique. (2016). “Jean-Marie Le Pen fined again for dismissing Holocaust as detail,” The Guardian, April 6, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/06/jean-marie-le-pen-fined-again-dismissing-holocaust-detail

Connolly, Kevin. (2016). “Grandfather of populism Poujade who shook France and the world,” BBC News. December 22, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-38370962

Davies, Peter. (2012). The National Front in France: Ideology, Discourse and Power. Routledge.

Dearden, Lizzie. (2017). “French elections: Marine Le Pen vows to suspend immigration to protect France,” Independent, April 18, 2017. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/french-elections-latest-marine-le-pen-immigration-suspend-protect-france-borders-front-national-fn-a7689326.html

Nossiter, Adam. (2017). “Marine Le Pen Echoes Trump’s Bleak Populism in French Campaign Kickoff,” The New York Times, February 5, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/05/world/europe/marine-le-pen-trump-populism-france-election.html

Riding, Alan. (2003). “Pierre Poujade Dies at 82; Rallied France’s Rightists,” New York Times. August 9, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/29/world/pierre-poujade-dies-at-82-rallied-france-s-rightists.html

Quigley, Aidan. (2017). “Trump expresses support for Le Pen,” Politico, May 21, 2017. https://www.politico.eu/article/trump-expresses-support-for-french-candidate-le-pen/

Shields, James. (2007). “The Extreme Right in France: From Pétain to Le Pen,” Routledge: 126-28.

[1] These are: The National Rally (Rassemblement national); Unsubmissive France (La France insoumise); The French Communist Party (Parti communiste français); France Arise (Debout la France); The National Republican Movement (Mouvement National Républicain); The Movement for France (Mouvement pour la France).