Turkey

The Republic of Turkey’s quest to modernize sowed the seeds of populism. For decades, the ruling Kemalists tried to assimilate the country into the ideal laicist, Sunni Muslim, and ethnically Turkish citizen; in the process, they vilified non-Muslims, non-Sunnis, non-Turks, non-laicists, and Islamists. Against this background, the AKP constructed itself as the only true representative of the victimised Sunni Muslim people and framed the Kemalists as “the evil elite.” The AKP’s rise and growing authoritarianism has led these fissures to fracture, reshaping the dynamics of Turkish populism. The AKP is constantly evolving; lately, it has been using Islamism and “external threats” to assume more control. The AKP retains some features of Kemalist “otherization” in the context of non-Sunni, non-Turk, and secular communities. The political opposition has also used populism to counter the AKP.

The modern-day Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923. The country has its roots in pre-antiquity and traces back to one of the oldest human settlements in the world. The Greek, Byzantian, and Ottoman Empires have been major cultural influencers (Gorke, 2014). For centuries the region was ruled by the Byzantine (Orthodox Christianity) and Ottoman (Sunni Islam) Empires. During their reign, the Ottomans were of major symbolic importance to Muslims across the world. While religion played a huge role in the Empire, Ottoman society was highly diverse; it attracted and hosted various faiths and ethnicities.

After the Ottomans were defeated in the First World War (WWI), huge portions of the empire were dismantled. The Empire’s institutional deterioration predated the Great War’s events. Its final incapacitation paved the way for a military-led Turkish War of Independence that expelled several occupying forces, established a provisional government, abolished the Ottoman Caliphate, and negotiated the future of the country under the Treaty of Lausanne (Turnaoğlu, 2017).

Mustafa Kemal – or Atatürk (Father Turk) – the founding leader of Turkey, aimed to modernize the country. Kemalist principles envisioned a “modern” country rooted in Republicanism, Populism, Nationalism, Laicism, Statism, and Reformism (Karabelias, 2009). Under Kemalism, several ethno-lingual-religious identities were squashed or Turkified: for example, Kurds and Alevis. Traditionally, the quest to secularize and Turkify was driven by insecurities. Kemalists yearned to be a part of Western civilisation. This led the state to forfeit its position in the Muslim (Sunni) world and pursue “modernism” (Saral, 2017). This policy caused huge ethno-religious rifts.

The citizens of Turkey have, for decades, been tossed into various “camps.” Initially, the “people” were the Kemalists. The group was built on Turk ethnicity and secularism and was used to generate a strong nationalist ethos (Berkes 1964). This ideology’s “other” were religious conservatives and those who did not assimilate into Turkish identity due to ethnic and linguistic distinctions (Yilmaz, 2021). Though Kemalists were able to displace a 600-year-old Empire thanks to the shock of World War I, uprooting the religious sentiments and ethno-lingual plurality of Anatolia was a Sisyphean quest for the Kemalists (Karabelias, 2009).

After significant decades of turmoil, Turkey’s economic indicators improved significantly in the early 2000s, under the stewardship of the Justice and Development Party (AKP). Neo-liberal reforms and welfare-oriented policies have led this growth. Income inequality remains a pressing issue. The last few years have seen a rise in unemployment coupled with the devaluation of the Turkish Lira (World Bank, 2020).

At present, majoritarian Islamist populism has become the new voice of “the people.” The formerly oppressed, rural and conservative populace now views the Kemalists as the “evil elite.” They are viewed as corrupt puppets of Western powers who have betrayed their Ottoman heritage. The “pious, pure people” are now taking back control of their country (Aytaç & Elçi, 2019; Karabelias, 2009). The vilification of non-Muslims and non-Turk ethnicities is a core part of Islamist populism in Turkey.

This Islamic populism has deep roots in Turkey. Its earliest manifestation emerged when the Democrat Party (DP) came to power in Turkey’s first free and fair elections, in 1950. The DP’s populist right-wing agenda was in direct opposition to the Kemalist Republican People’s Party (CHP). The DP was banned in Turkey following the first military coup d’état in the Republican era, in 1960 (Aytaç and Elçi, 2019).

Through the latter half of the 20th century, right-wing Islamist populist parties surfaced only to be crushed by the Kemalist military through either direct interventions or judicial means. Charges of violating the secular constitution were often the reasons cited for these crackdowns.

The cyclical ban and resurfacing of populist Islamist parties continued until 2001, when the AKP emerged as a continuation of the banned Virtue Party (Fazilet Partisi – FP). The AKP distinguished itself as a centre-right party. Its predecessors, including the Welfare Party (Refah Partisi – RP), National Salvation Party (Milli Selamet Partisi – MSP), and the National Order Party (Milli Nizam Partisi – MNP), followed the far-right Islamist Millî Görüş (National View) political narrative. This centre-right position gave the AKP legitimacy as a “Muslim Democratic” party (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018).

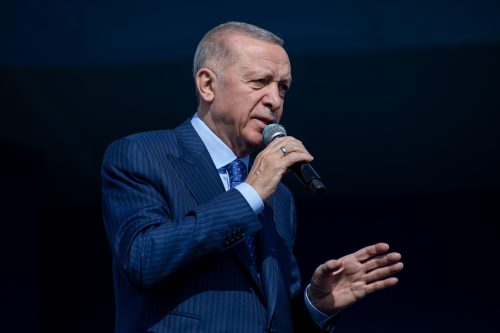

Its leaders, such as Recep Tayyip Erdogan, display populist hallmarks such as the use of crude language, a confrontational style, and working-class backgrounds to identify with “the people.” Reform was at the heart of the AKP’s early election pledges. It promised welfare policies and liberalization. Its ambitions were to integrate Turkey with the European Union (EU) and get rid of the Kemalist military tutelage (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018).

The party came to power in 2002; since then, Erdogan has led the party through many changes. The AKP started off with the mission of joining the EU. As a result, a huge number of economic and social reforms were realized. Thus, the party’s first decade was marked by economic progress and hope that relations between Turkey’s various communities might be improved. For instance, the AKP promised to return confiscated religious properties or pay reparations to non-Muslim groups. It opened a dialogue with Armenians, offering a joint investigation into the Armenian genocide. The party signed a ceasefire agreement with Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). At the same time, it improved the average citizen’s access to public facilities (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018).

With these changes underway, the AKP increasingly positioned itself against the Kemalist strongholds in the military and judiciary. In 2010, a referendum was held following the controversial Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials, which exposed alleged treason by military officials. The 2010 referendum paved the way for more political control over the judiciary (Yilmaz, Barton & Barry, 2017; Şahin & Hayirali, 2010).

By its third term in power, the AKP turned harder into populism (Yilmaz, Caman, & Bashirov, 2020). As Turkey’s EU prospects dimmed, the economy began to struggle. Domestic terrorism surged. These events led to increasing public unrest, such as the 2013 Gezi Park protests. protests Finally, the failed coup attempt, on July 15, 2016, led the AKP and Erdogan to move the country definitively towards authoritarianism justified by populism (Yilmaz, Barton & Barry, 2017).

Post-2013, anti-elite or anti-Kemalist rhetoric did not suffice. Islamism was introduced as a key pillar of the AKP’s populism (Yilmaz and Bashirov, 2018). The party has increasingly invoked nostalgic associations with the Ottomans. The AKP’s nationalism is now rooted in right-wing Islam and Ottoman nostalgia (Yilmaz, 2018). The reconversion of Hagia Sophia and the Church of the Holy Saviour, Chora, to mosques are examples of Islamist populism’s clear manifestations. The Erdogan regime has also used the Diyanet (the Directorate of Religious Affairs) to spread its populist religious narrative. Under these circumstances, non-Sunnis and non-Muslims have been otherized. The AKP has also used both soft and hard power to influence “brother” Muslim countries, in an effort to build support for Turkey (Serhan, 2020; Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018).

Under its grand narrative, the AKP has increasingly invoked threats from “outside powers” and “traitors from within” as excuses to jail thousands of dissenting voices. Following the 2016 coup attempt, those targeted include members of the Gulen Movement, critical academics, and journalists (Yilmaz, 2018).

In addition to the use of populist narratives, the party has employed clientelism, neo-patrimonialism, coercion, and intimidation as means of consolidating power. The constitutional changes by the AKP – through referendums in 2010 and 2017 – allow the President to handpick the highest-ranking state officials, from judiciary members to university rectors (Serhan, 2020; Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018).

AKP leadership has increasingly concentrated around the personality cult of their populist leader, Erdogan. This populist rhetoric revolves around building a “New Turkey” (Yilmaz, Caman and Bashirov, 2020). This new regime vows not to repeat the mistakes of the past (such as giving up on its Ottoman heritage). The victimised and grieving “Black Turks” – or common people (Sunni Muslim conservatives) – are now the rightful and only loyal citizens. The AKP is “struggling” to regain their “glorious” position in the country and in the world. Opposition towards the AKP is equated to inciting terrorism. According to the current regime, the pro-Kurdish or pre-Western opposition wish to “harm” Turkey and hinder its path to “greatness.”

Decades of Kemalism followed by the AKP’s reckless change in Turkey’s narrative have led to polarization, division, and emotional fault-lines in Turkish society. To counter the AKP’s populism, the same strategy is being used by the opposition. It should be noted that opposition to AKP is not an easy task. The party tends to absorb populist opposition into itself. For example, the People’s Voice Party, (HAS Party) was an infant right-wing party which was absorbed by the AKP. The direct intervention of Erdogan gave the former party’s leader, Numan Kurtulmus, a key position in the AKP (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018). While the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) is an ultra-nationalist, right-wing populist party, it has also used Islamism to find conservative voters not captured by the AKP. In 2015, the AKP co-opted the MHP, too, by drumming up fears about the pro-Kurdish HDP. In 2018, the AKP formed a formal alliance called the People’s Alliance (Cumhur Ittifaki) (Yilmaz, Shipoli and Demir, 2021). Right-wing efforts to counter the AKP have mostly been swallowed up by it.

The Kemalist CHP has also used populism to counter Erdoganism. Led by Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the party has remained true to its Kemalist nationalist ideals. While Kilicdaroglu brings a leftist touch to the party, at its core, the party is still Kemalist. The CHP now uses populist leftist rhetoric in light of the AKP’s coercive policies and increasingly failing economic measures (Gulmez, 2013). However, it remains far from being a fully functional opposition. The CHP mostly remains silent against the AKP. It has neither pointed out election fraud nor has it been directly critical of the AKP’s ultra-nationalist, Islamist narrative has so divided the country (Yilmaz, Caman, & Bashirov, 2020). Ironically, in a pragmatic move, the CHP has not shied away from cooperating with other Islamist parties in a bid to synergise populist anti-establishment and anti-Erdogan sentiments (Tekdemir, 2018).

The İYİ Party, another Kemalist party, has also followed the CHP’s pattern. For example, it fails to lend support to the targeted Kurdish community; nor has it pointed out the massive human rights abuses of the AKP-led regime. Thus, the National Alliance is a populist opposition rooted in Kemalist principles as opposed to the Islamist ideations of Erdoganism, rather than a genuine political opposition (Yilmaz, Caman, & Bashirov, 2020).

Following the Gezi Park protests in 2013, the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) emerged as the legitimate left-leaning opposition in Turkey. The HDP in its own way uses a different form of populism. While the HDP has its roots in humanism, the political climate has forced it to define itself as “the people.” The HDP’s people are those who seek a pluralistic society. It aims to bring Muslims, Alevis, LGBTQ, and non-Muslims together to build a liberal democratic society. It does not otherize the Kemalists and Erdoganists. Its populism is “anti-elite” and “anti-fascist” (Tekdemir, 2018). The HDP’s “outsider” status as a new party, as well as its pro-Kurdish stance, has made it a popular choice for those who did not find these elements in conventional populist parties. Viewing it as a threat, the AKP has weeded out locally elected mayors from the HDP and key party leadership have been labelled “terrorists”; many of them have been imprisoned. Their pro-Kurdish stance has been used to legitimize coercive powers to limit the party’s functioning (Elci, 2019).

Populism has become mainstream in Turkish politics. The AKP has used it to amass power and control the political narrative. However, as recent research (Yilmaz, Caman, & Bashirov, 2020) shows, many aspects of the Turkish version of populism – such as ethnic nationalism, the intense triggering of emotions for political mobilisation, sacralising the state and its leaders, ontological insecurity, an inferiority complex vis-à-vis the West, a politics of fear and victimhood, clientelism, and nostalgia for Turkey’s “great” past – are also shared by other political parties such as the CHP, MHP, and IYI.

By Ihsan Yilmaz

February 18, 2021

References

— (2020). “The World Bank in Turkey.” World Bank. Oct. 15, 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/turkey/overview (accessed January 11, 2020).

Aytaç, Erdem, S. and Elçi, Ezgi. (2019). “Populism in Turkey.” Populism Around the World. http://home.ku.edu.tr/~saytac/uploads/Aytac_Elci_Populism_in_Turkey_2018.pdf (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Berkes, N. (1964). The development of secularism in Turkey. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press.

Elçi, Ezgi. (2019). “The Rise of Populism in Turkey: A Content Analysis.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. August 26, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2019.1656875 (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Gorke, Susanne. (2014). “A Handbook of Ancient Anatolia.” The Classical Review. 64(1), 179-81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43301840 (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Gülmez, S.B. (2013). “The EU Policy of the Republican People’s Party under Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu: A new wine in an old wine cellar.” Turkish Studies. 14(2), 311–28. doi:10.1080/14683849.2013.802924 (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Karabelıas, Gerassımos. (2009). “The Military Institution, Atatürk’s Principles, and Turkey’s Sisyphean Quest for Democracy.” Middle Eastern Studies. 45(1), no. 1, pp. 57–69. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40262642 (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Saral, Melek. (2017). Turkey’s ‘Self’ and ‘Other’ Definitions in the Course of the EU Accession Process. Amsterdam University Press. 2017. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1zxskmw (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Serhan, Yasmeen. (2020). “The End of the Secular Republic.” The Atlantic. Aug. 13, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/08/modi-erdogan-religious-nationalism/615052/ (accessed on January 8, 2021).

Şahin, Omer and Hayirli, Dilek. (2010). “What will the Sept. 12 referendum bring?” Today’s Zaman. Aug. 8, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20121010013031/http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/news-218436-what-will-the-sept-12-referendum-bring.html (accessed on January 5, 2021).

Tekdemir, Omer. (2018). “Turkey’s three-dimensional populism, three leaders and three blocs.” Open Democracy. June 18, 2018. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/turkey-s-three-dimensional-populism-three-leaders-and-three-blocs/ (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Turnaoğlu, Banu. (2017). The Formation of Turkish Republicanism. Princeton University Press. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1q1xsr7 (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Yilmaz Ihsan (2018). “Islamic Populism and Creating Desirable Citizens in Erdogan’s New Turkey.” Mediterranean Quarterly. 29 (4), 52–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10474552-7345451 (accessed on January 12, 2021).

Yilmaz, Ihsan. (2021). Creating the Desired Citizen: Ideology, State and Islam in Turkey. Cambridge University Press.

Yilmaz, Ihsan; Barton, Greg & Barry, James. (2017). “The Decline and Resurgence of Turkish Islamism: The Story of Tayyip Erdoğan’s AKP.” Journal of Citizenship and Globalisation Studies. 1(1): 48–62.

Yilmaz, Ihsan & Bashirov, Galib. (2018). “AKP after 15 Years: Emergence of Erdoğanism in Turkey.” Third World Quarterly. 39(9): 1812-1830.

Yilmaz, Ihsan; Caman, Mehmet Efe & Bashirov, Galib. (2020). “How an Islamist party managed to legitimate its authoritarianization in the eyes of the secularist opposition: the case of Turkey.” Democratization. 27(2), 265-282. DOI: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1679772

Yilmaz, İhsan; Shipoli, Erdoan & Demir, Mustafa. (2021). “Authoritarian Resilience through Securitisation: An Islamist Populist Party’s Co-optation of a Secularist Far-Right Party.” Democratization. DOI: 10.1080/13510347.2021.1891412