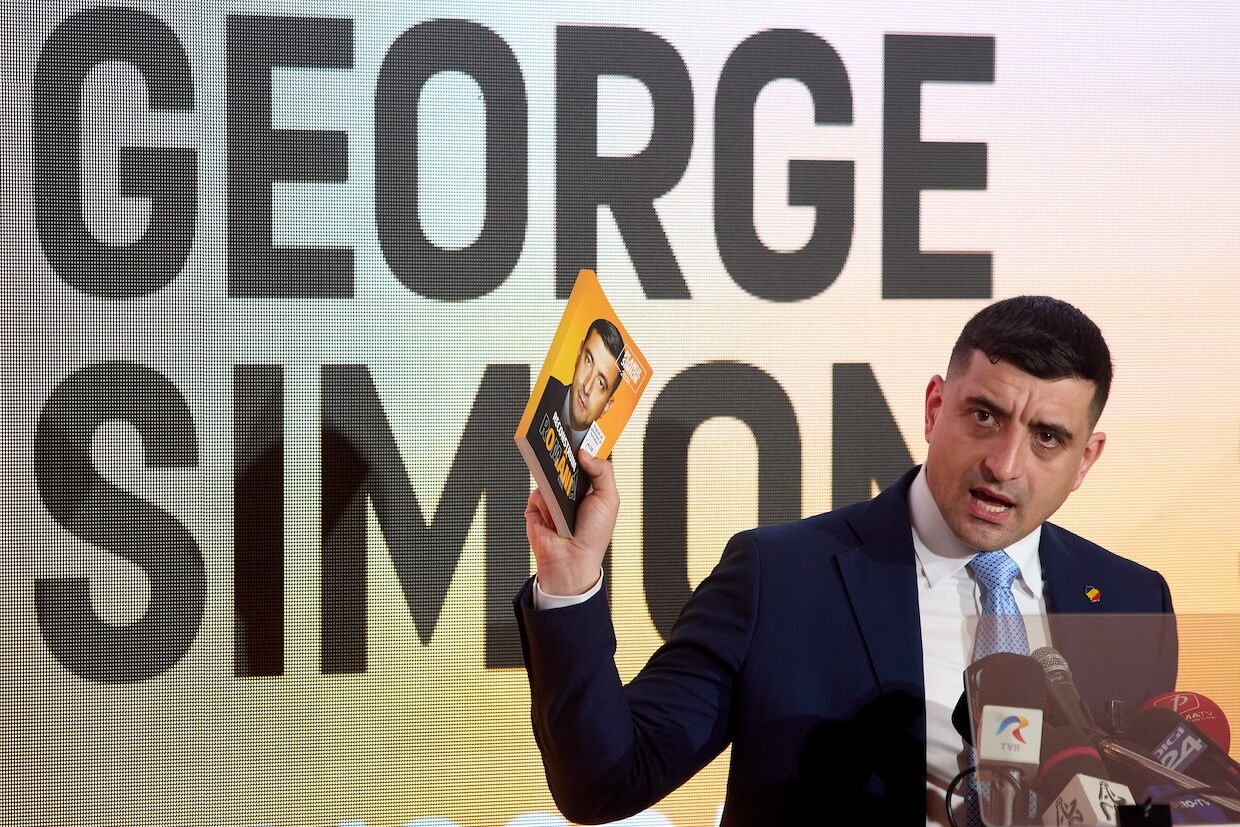

In an in-depth interview with the ECPS, Dr. Claudiu Tufiş, explains how far-right candidate George Simion’s success in the first round of Romania’s presidential elections on Sunday was driven by widespread voter anger and disappointment following the annulment of the original vote. “Voters were deeply disappointed by the cancellation of the elections,” he notes, “and many reacted with anger, leading to a noticeable erosion of trust in the electoral process.” With no credible democratic opposition and growing anti-establishment sentiment, Simion was able to capitalize on public frustration. Dr. Tufiş’s analysis sheds critical light on the structural and emotional undercurrents reshaping Romanian politics.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In the wake of Romania’s highly polarized first round of presidential elections on Sunday, Dr. Claudiu Tufiş, Associate Professor of Political Science at the Faculty of Political Science at the University of Bucharest, provides a deeply analytical account of the socio-political dynamics that have propelled far-right candidate George Simion to the forefront of the political stage. Speaking with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Tufiş underscores a central factor behind Simion’s electoral surge: widespread public anger and disillusionment following the annulment of the 2024 presidential vote.

“When it comes to Simion’s results, they might seem like a surprise, but they really shouldn’t,” Dr. Tufiş observes. “If you look at the share of votes received by sovereigntists or extremists—however one chooses to label them—in the annulled first round of the November presidential elections, Simion and Georgescu together garnered over 30%.” In his view, the subsequent backlash—intensified by the disqualification of Călin Georgescu—created a perfect storm of grievance-driven mobilization: “Romanian voters were deeply disappointed by the cancellation of the elections, and many reacted with anger, leading to a noticeable erosion of trust in the electoral process.”

Simion’s first-round performance, securing 41% of the vote, represents more than a statistical anomaly. As Dr. Tufiş explains, “Basically, they had almost six months—from November until now—to coalesce more and more around the idea that somebody should pay for that decision to cancel the elections, and Simion was at the center of this movement.” The professor emphasizes that Simion’s rise is not merely an ideological success, but rather the product of a profound anti-establishment sentiment amid institutional instability.

Throughout the conversation, Dr. Tufiş unpacks the deeper structural factors shaping this moment: the erosion of confidence in Romania’s mainstream parties, the political mishandling of crises like the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war, and the failure of democratic opposition forces to present a credible alternative. The result, he warns, is “not really a surprise”—but rather the culmination of years of frustration, disillusionment, and unaddressed socio-economic inequality.

This interview offers a timely and urgent insight into how electoral grievance, institutional decay, and populist strategy have converged to reshape Romanian politics. As Romania prepares for the second round of voting on May 18, Dr. Tufiş’s reflections provide a sobering lens on what is at stake—for democracy, for the region, and for Europe at large.

Here is the lightly edited transcript of the interview with Dr. Claudiu Tufiş.

Simion Became the Focal Point for Voters Who Felt Betrayed by the Election Annulment

Professor Tufiş, thank you so very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: What is your assessment of the first round of presidential elections in Romania, as the candidate of the far right, George Simion, got almost 40% of the vote? What is your prediction about the second round of the elections that will be held on May 18?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: Yes, George Simion won probably more than most people were expecting. In the first round, he managed to gather the support of 41% of voters, and in second place, we have a candidate from what’s considered to be a pro-European position—an independent, Nicușor Dan, who is the mayor of Bucharest.

When it comes to Simion’s results, they might seem like a surprise, but they really shouldn’t. If you look at the percentage of votes that the sovereigntists, the extremists—however you want to call them—received during the November first round of the presidential elections, the ones that were cancelled, Simion and Georgescu together got more than 30% of the vote. So it’s not unexpected. Voters in Romania were really disappointed with the decision to cancel the elections, and they got really angry. They lost trust in the electoral process to some extent. And basically, they had almost six months—from November until now—to coalesce more and more around the idea that somebody should pay for that decision to cancel the elections, and Simion was at the center of this movement. He was the one who captured the votes of all the disappointed voters in Romania. So from that perspective, an increase from 30-something percent to 41% over five months with people really disappointed about the decision—it’s not really a surprise.

As for what will happen two weeks from now, that is a little bit more difficult to predict. Of course, Simion has the first chance. He only needs 9–10% more than what he already gathered in the first round, and that is relatively easy to collect. The problem is that both candidates in the second round—Simion and Nicușor Dan—have already started negotiating with all political parties. Just last evening (Monday), the governing coalition broke up. The Prime Minister decided to resign. The leadership of the Social Democratic Party is also resigning. So everything is in flux right now. The Liberals decided on Monday that they will support Nicușor Dan in the second round of elections. The Social Democrats said they are not going to support either of the two candidates—they’re leaving it up to voters to decide.

But these are just public statements made by political parties. Behind closed doors, from what I hear, there are very heated debates and negotiations as parties try to figure out what the next majority will look like after the elections. So right now, we are in a period of flux, and even if I were a betting man, I couldn’t say for sure which of the two candidates is going to win. The only thing I know for certain is that George Simion currently has the advantage. It’s a lot easier for him to get to 51% compared to Nicușor Dan.

Voters Turned to AUR After a Decade of Disillusionment and Crisis Mismanagement

As you noted in your studies, Romania was once a partial exception to the populist wave. What underlying shifts—political, social, or institutional—do you believe have led to the resurgence and normalization of far-right populism?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: I think there are several elements here. But probably the most important one we should focus on is the fact that, for quite some time, we’ve had only the Social Democrats or the Liberals in power in Romania. These two political parties, ever since 2012, have governed either together or alone. To some, that might seem like a lack of alternation in power, a lack of refreshment in the political scene, and the result has been increasing public disappointment with these two main political forces.

Usually, when people are unhappy with the incumbents, they turn to the opposition. The problem with the 2024 elections in Romania was that we didn’t really have a strong democratic opposition party. If you set aside the governing parties—the Liberals and the Social Democrats—the remaining parties in Parliament were the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), led by George Simion, the party representing the Hungarian minority, and the Save Romania Union (USR), which was originally led by Nicuşor Dan. But Nicuşor Dan had to leave the party because he could no longer identify with its direction.

Theoretically, the democratic opposition should have been the USR. But the party disappointed its voters. Instead of growing after its 2016 breakthrough, when it got about 10%, it became consumed with internal power struggles. That led to a lot of voter disappointment. As a result, by 2024, many discontented voters were left with only one viable option—AUR—as the repository of their frustration.

There’s also a second element: the Social Democrat–Liberal coalition governed through two major crises. Both were global or regional in scope but had a serious impact on Romania. I’m talking about the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

The pandemic, of course, brought lockdowns—not as strict as Italy’s, but not as lenient as Sweden’s either. What caused significant discontent was the push for vaccination. While vaccination wasn’t mandatory, it was heavily promoted by the government. Romania has a significant portion of the population that is skeptical about vaccines. In fact, Romania now has the highest number of children suffering from preventable childhood diseases due to low vaccination rates.

George Simion’s party saw this as an opportunity. They were the only political party that capitalized on that sentiment and used it to gather support. That was the first crisis. The second, of course, is Russia’s war on Ukraine, right on our border, with the influx of Ukrainian refugees and all the accompanying pressures.

So, we’ve seen the two main governing parties being eroded simply by being in power for a long time, a process worsened by the two crises. Meanwhile, there was no strong democratic alternative. In the end, people chose what was available: AUR and newcomers like Călin Georgescu—parties that sought to capitalize on AUR’s image and appeal to voters with similar messages.

How Culture Wars Replaced Old Divides in Romanian Far-Right Discourse

How do you interpret the redefinition of exclusionary discourse in Romanian far-right politics—from ethnic targeting to cultural and religious narratives? What explains this evolution in ideological framing?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: Romania had significant problems early in its transition with ethnic minorities—mainly with the Hungarian and Roma communities. Over time, however, we’ve managed to address those tensions to some extent. Today, there is relative peace between Romanian and Hungarian segments of the population. Occasionally, political parties try to reignite this conflict, but it generally doesn’t resonate—people no longer see it as a valid issue.

As for the Roma population, there are still negative perceptions among the broader Romanian public. But many Roma have migrated to other EU countries, so there’s less pressure now to activate that conflict politically.

The shift from ethnic or religious exclusion to identity- or culture-based narratives is, I think, partly due to a kind of mimicry of Western—mainly American—society. Issues like “woke culture” or “cancel culture” have been heavily criticized in other parts of the world, and these narratives have found fertile ground in Romania.

Romania remains a deeply traditional society, where there are widely accepted beliefs about fixed gender roles and a general resistance to discussions of gender equality or LGBTQ+ rights. This creates an environment where traditional misogyny and intolerance toward difference can be easily mobilized by political actors to boost support.

That’s why, for example, Romania attempted a referendum to redefine the family in the Constitution. It failed due to low turnout, but it reflected a broader regional trend in Eastern Europe—over the past decade—of pushing back against what are perceived as “new ideologies.”

And of course, there is a second element here: these ideologies and values are perceived as being imposed by the European Union and viewed as incompatible with Romanian traditions— with who Romanians are. As a result, these cultural conflicts have also fueled a broader pushback against the EU.

Simion Rides the Wave of Anti-Establishment Sentiment, Not Ideology

What do you see as the main drivers behind George Simion’s current popularity, particularly among younger voters and segments of the diaspora? To what extent is his appeal rooted in ideology versus anti-establishment sentiment?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: I would say that almost all of his appeal comes from anti-establishment sentiment and has little to do with ideology. George Simion has, at times, taken strong anti-European Union positions, but over time he realized that this message doesn’t resonate well with the Romanian public, so he has moderated his stance over the last two or three years. If you talk to regular voters in Romania, most of them will tell you what I mentioned earlier—they are sick and tired of seeing the same people governing the country for more than a decade.

This is evident in the candidates selected by the mainstream political parties for the presidency in both the annulled November elections and now—they are the same figures who’ve been at the center of power for the past 10 to 15 years, and people are simply unhappy with their performance. This time around, they want a change that is completely separate from the mainstream parties. That’s why voters seeking real change have turned to George Simion and his party.

Even Nicușor Dan, though he’s the Mayor of Bucharest and running as an independent, benefits from this desire for change. He was the founder of the Save Romania Union (USR), but he’s no longer a member, and USR is now a minor party. So Dan, too, is seen as detached from the traditional parties, though he appeals to a different voter base.

On Tuesday, some exit polls showed that Simion’s voters are generally less educated—he has a significant lead among those with only a high school diploma. By contrast, Nicușor Dan is mostly supported by voters with higher education—college degrees and above. So there’s a strong correlation between education level and candidate preference. And since education is often associated with income and wealth, the division essentially reflects a broader socioeconomic cleavage.

It’s a conflict between those who have benefited from Romania’s economic development over the past 10 to 20 years and those who have not. Romania has done well in terms of macroeconomic indicators, but the resulting wealth has not been evenly distributed. That inequality is being felt more acutely now.

So, in the second round of the presidential elections two weeks from now, we’ll see two candidates—both representing a break from the mainstream parties. George Simion represents change for those who feel left behind, while Nicușor Dan represents change for the educated, urban middle class that has benefited most from Romania’s recent growth.

Voters Wanted to Punish Those Who Canceled the Elections

The annulment of the 2024 presidential election and the disqualification of Călin Georgescu triggered strong domestic and international reactions, feeding into populist narratives of elite conspiracy and Western interference. How has this grievance-driven discourse shaped AUR’s electoral mobilization, and to what extent has public backlash against the court’s decision contributed to George Simion’s rise in popularity?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: It’s pretty much the same distribution of support for the two candidates as the one I’ve just mentioned. Both supporters of George Simion and of Nicușor Dan were unhappy with the decision to cancel the elections. Again, we’re looking at two groups in society: on one hand, the less educated and economically disadvantaged, who were angry because the annulment took away their candidate; and on the other hand, the more educated and financially secure, who were upset not necessarily because Călin Georgescu was barred, but because the annulment ran against democratic principles. So while the reasons differ, both groups share discontent with the court’s decision and want to punish those responsible.

This sentiment has played a significant role in mobilizing voters, particularly against the Social Democrats and the Liberals, who are widely seen as the ones responsible for canceling the elections and undermining the integrity of the electoral process. And it’s not just the annulment in December—these parties began interfering with the electoral system as early as June, when they decided to hold the local and European Parliament elections simultaneously. As a result, public debate focused solely on local issues, with little to no discussion about Romania’s role in the EU or what Romanian MEPs could accomplish in Brussels.

Later came the decision to ban Diana Șoșoacă from running in the election, which many also interpreted as a move by the governing parties to rig the process in their favor and secure an easy path to the second round. When voters perceive those in power as manipulating electoral rules to their own advantage, they’re going to respond by punishing them at the ballot box.

For Those Who Study Politics, the Election Results Weren’t a Surprise

The surge in support for far-right candidates like Georgescu and Simion—especially in light of their previous low polling—has been described as ‘shocking’. Do you agree with this characterization, or were there early indicators that mainstream analysis missed?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: I wouldn’t necessarily say it was shocking. I mean, it was probably shocking for people who don’t pay close attention to the political system and political actors. But for those of us who study politics, it wasn’t much of a surprise. Călin Georgescu may have appeared as a surprise to most voters, but if you look at his background, you’ll see that since the mid-1990s he was close to the center of political power. He worked at important ministries, and throughout the 2000s he was often discussed as a potential prime minister. Not more than four or five years ago—in 2020, during the last round of parliamentary elections—AUR actually proposed Călin Georgescu as prime minister during their consultations with the president.

Georgescu managed to construct the image of a new political actor largely because he held many of his positions abroad and wasn’t very visible in domestic politics. But in reality, he was not new to the political scene. The same goes for Simion. He’s not new either—he’s been active in Romanian politics and civil society since around 2010. So both are seasoned political actors who have spent years building their public presence—through activism, civic engagement, and later, political organization.

They built their support bases by channeling the discontent of voters fed up with the political establishment. In Romania, from 2012 to 2015, there was a notable shift in public political attitudes, marked by a significant wave of protests following various poor decisions and crises. That moment gave rise to movements like the Union Save Romania Party (USR) in 2015—emerging from the technocratic government—and eventually AUR as well. These two parties essentially originate from civil society and were created as vehicles to push people’s demands into the political sphere. Because as civic organizations, there’s a limit to what can be achieved. What we’re seeing now is the culmination of about a decade of organizing, during which these movements developed into serious political forces.

Romania Is Backsliding—Not Drastically, but Persistently

In the light of recent political events—including the annulled 2024 vote and US criticism of Romania’s handling of Georgescu’s candidacy—do you believe Romanian democracy is entering a phase of greater polarization or institutional erosion?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: This is really just the latest example of Romania backsliding a bit. There are two elements I would discuss here.

The first is polarization within the population. This has been present in Romanian society for quite some time. Since the beginning of the post-communist regime, we’ve had significant cleavages dividing the population. Initially, it was the communist versus anti-communist cleavage, which later transformed into a divide between supporters and opponents of the Social Democrats. In recent years, this has evolved further, but at its core, it reflects a broader tendency in Romania to avoid negotiation and compromise.

This is largely a product of the past 10 to 15 years, during which politics in Romania has been treated as a zero-sum game. Politicians refused to engage in dialogue, and people followed their lead. If political leaders are constantly in conflict and unwilling to talk, we can’t expect their supporters to behave any differently. So polarization has been very high for quite some time now—and it’s a serious issue. As a society, we need to be able to sit at the same table and ask: What do we want for the next five or ten years? How do we envision Romania’s future?

The second element is institutional. Romania has been slow to implement democracy. It progressed up to a certain point, and then politicians began tampering with democratic processes. They pitted branches of government against one another. Under Băsescu’s presidency, for instance, the parliament was regularly attacked and de-legitimized. At times, the judiciary was also pressured, with politicians attempting to assert control. Over the last decade, Romania has started to decline—not dramatically like Poland under PiS or Hungary under Viktor Orbán, but after a long period of stagnation, we’ve seen a gradual backslide in specific areas of democracy.

This democratic erosion has also been aided by low levels of civic engagement. Romanians don’t have a strong history of participation in politics or civil society. Compared to neighboring countries, we show lower levels of civic activism, and this has played a role. If politicians don’t feel public pressure—if no one is calling them out for failing to meet their responsibilities—they quickly realize they can act without consequences. It’s only when something particularly egregious or morally offensive happens that the public reacts and protests.

You may recall several major protests in Bucharest and other large cities, but when it comes to the day-to-day work of building institutions or holding parties accountable, that kind of sustained civic involvement is less common. Unfortunately, we’re still learning.

AUR’s Strategy Blends Traditionalism with Tactical Euroscepticism

AUR’s ideological framing includes Orthodox values, anti-globalism, and an ambiguous stance toward NATO. How does this fit into the broader regional trend of radical-right parties navigating between nationalism and global alignments like MAGA or Kremlin narratives?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: George Simion has been accused multiple times of being controlled by the Russians, though I’m not sure that accusation is substantiated—I haven’t seen any significant evidence linking him directly to Russia.

As for the other elements, AUR—the Alliance for the Union of Romanians—bases its ideological framing on several key pillars, which they present as central to Romanian identity. These are: the Orthodox Christian religion; the traditional family; Romanian cultural traditions; and the Romanian nation itself. These four values form the ideological foundation of the party.

Naturally, all four of these pillars align with a traditionalist worldview. AUR uses them to construct narratives that oppose what they see as external threats—particularly from the European Union. The EU isn’t framed explicitly as an enemy, but rather as a force that undermines these core values. For instance, AUR argues that the EU lacks true religious conviction and therefore poses a threat to the church. On the issue of family, they interpret any discussion around gender ideology or LGBTQ rights as a direct attack. Their vision of the family is strictly heterosexual and reproductive—only a man and a woman with children qualify as a legitimate family.

Tradition is the third pillar, and again, anything coming from the EU is painted as being out of step with or even hostile to Romanian cultural traditions. In this way, AUR initially positioned itself in stark opposition to the EU. However, they gradually realized that most Romanians still support EU membership. Many citizens view it as a net positive, citing benefits such as economic development, the ability to travel and work abroad, and enjoying the same rights as people in Germany, France, and Italy. Eventually, AUR understood this and began to tone down its anti-EU rhetoric. However, they continue to promote messages centered on identity and values, which they still use to their political advantage.

Simion Lacks the Team to Secure Romania’s Strategic Commitments

Given Romania’s strategic role in NATO, its support for Ukraine, and its position within the EU, what might a George Simion presidency mean for the country’s foreign policy orientation and regional stability? Could his leadership signal a shift away from Romania’s pro-Western trajectory, potentially making it a more disruptive force within transatlantic alliances?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: It’s certainly the worst outcome—having Simion as president—if we are thinking about Romania’s role externally. Looking at the geostrategic position of Romania, it’s part of the eastern border of NATO, part of the eastern border of the European Union. We already have Ukraine being destabilized, and Slovakia and Serbia—close neighbors or just the next country over—presenting challenges.

There is a growing sense that countries in the region are not advancing as they should, and if Simion were to become president, I fear Romania will start moving in that direction as well. This is probably the most worrying consequence of Simion winning the presidency: that he would destabilize Romania.

Part of the potential destabilization comes from the fact that, although Simion is very popular—as we’ve seen in the vote count—he doesn’t have a strong team around him. Everything we know about George Simion comes from himself or maybe one or two others. We don’t know who his advisers are on foreign affairs, economics, or military issues. There doesn’t seem to be a substantial, competent team behind him who could assume office and fulfill Romania’s responsibilities as a NATO member. From that perspective, it is worrying, and I would say the eastern flank of NATO would be destabilized.

There are, of course, a number of possible solutions to this. Romania should probably seek a stronger alliance with Turkey. Unfortunately, at this moment, we don’t have particularly strong relations—just standard diplomatic ties. Given Turkey’s regional power, I would say this is one area where Romania should look for support in building alliances. Poland is another strong regional actor that Romania should align with more closely.

But again, these are probably not the kinds of decisions George Simion would make as president. We’ll see how it goes. Regardless of whether Simion or Nicușor Dan becomes president, there is an upcoming summit in just over a month. That will be the first significant international meeting for the new president, and it will likely reveal more about the foreign policy direction Romania will take.

Trump Isn’t Backing Anyone—We’re on Our Own

Professor Tufiș, finally, how much do you think US President Trump’s policies have affected elections in Romania?

Dr. Claudiu Tufiş: I lived for six years in the United States—I consider it a second home. However, the current administration is difficult for me to understand. I don’t fully grasp why Trump is making some of the decisions he’s made. So I don’t see, or understand, what his current vision for Romania is. Let’s put it that way.

Of course, there have been some signals from the US administration. There have been high-profile visits to Romania, and some of these figures have met with George Simion. It seems like George Simion might be supported by the American administration.

But I’m not sure if that’s actually the case. Given Trump’s outspokenness, if he truly supported George Simion, he would have absolutely no trouble saying it publicly—and so far, he hasn’t. What the American administration has done is criticize the Romanian Constitutional Court’s decision to annul the elections. But again, we’ve just seen a couple of days ago that they also criticized Germany’s decision to label AfD as an extremist organization.

This administration plays very loosely with words, and they don’t follow the traditional diplomatic customs of avoiding interference in other countries’ domestic politics. So I think it’s more about the Trump administration promoting a different kind of democracy than about offering support for a specific candidate in Romania.

They do have troops and military bases in Romania, and there has been significant cooperation—especially military cooperation—both within NATO and bilaterally. But I don’t think Trump currently supports any particular Romanian candidate. So I don’t expect any such endorsement in the next two weeks. We’re on our own. We have to decide for ourselves who we’re going to vote for.