Professor Sandra Ricart delivered a timely and insightful lecture on the intersection of climate change, agriculture, and populism in Europe. She explored how structural and demographic challenges, including a declining farming population and economic precarity, have fueled widespread farmer protests across the continent. Prof. Ricart emphasized how these grievances, while rooted in genuine hardship, have increasingly been exploited by far-right populist movements eager to position themselves as defenders of rural interests against European institutions. Her analysis highlighted the pressures created by climate change, policy reforms, and global market dynamics, and she called for more inclusive, responsive, and sustainable agricultural policies. Prof. Ricart’s lecture provided participants with a critical understanding of rural Europe’s evolving political and environmental landscape.

Reported by ECPS Staff

The ECPS Academy Summer School 2025, held online from July 7–11, 2025, brought together scholars and participants under the theme “Populism and Climate Change: Understanding What Is at Stake and Crafting Policy Suggestions for Stakeholders.” On Tuesday, July 8, 2025, the third lecture of the program featured Professor Sandra Ricart, who delivered an insightful presentation titled “Climate Change, Food, Farmers, and Populism.”

The session was moderated by Dr. Vlad Surdea-Hernea, postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Forest, Environmental and Natural Resource Policy at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna. Dr. Surdea-Hernea’s research on the intersection of populism, climate, and democracy provided a fitting context for introducing Professor Ricart’s work.

Prof. Sandra Ricart is a Professor at the Environmental Intelligence for Global Change Lab within the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering at the Politecnico di Milano, Italy. A geographer by training, she holds a PhD in Geography – Experimental Sciences and Sustainability from the University of Girona (2014) and has held research positions in Spain, Italy, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the United States. Her research focuses on climate change narratives, farmers’ perceptions, adaptive capacity, and participatory environmental governance. She is also Assistant Editor for the International Journal of Water Resources Development and PLOS One, and serves as an expert evaluator for the European Commission.

At the outset of her lecture, Prof. Ricart emphasized that her presentation was grounded in a collective, collaborative research tradition—a reflection of shared knowledge developed through interdisciplinary and cross-national scholarly networks. Acknowledging the diversity of her audience’s expertise, she framed her lecture as both a conceptual overview and an empirical analysis, blending theory with practical illustrations drawn from recent European developments.

Her talk was organized around several key themes: an overview of the structural and demographic features of European agriculture, public and farmer perceptions of climate change and agricultural policy, the socioeconomic challenges farmers face, and the role of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) as Europe’s primary agricultural governance framework. She explained how these structural factors intersect with climate change impacts, shaping both agricultural livelihoods and political discourses.

A central theme of Prof. Ricart’s lecture was how recent farmer protests across Europe reflect not only deep-seated socioeconomic grievances but also how these grievances have been increasingly co-opted by far-right populist movements. She raised the critical question of whether this emerging nexus between agricultural discontent and populism represents a transient political episode or the early stages of a deeper realignment in European rural politics.

Throughout the session, Prof. Ricart’s analysis provided participants with a nuanced, multi-scalar understanding of how climate change, policy pressures, and populist narratives are converging on European farming communities, offering a timely foundation for further reflection and debate on rural Europe’s evolving political landscape.

Structural and Demographic Features of European Agriculture

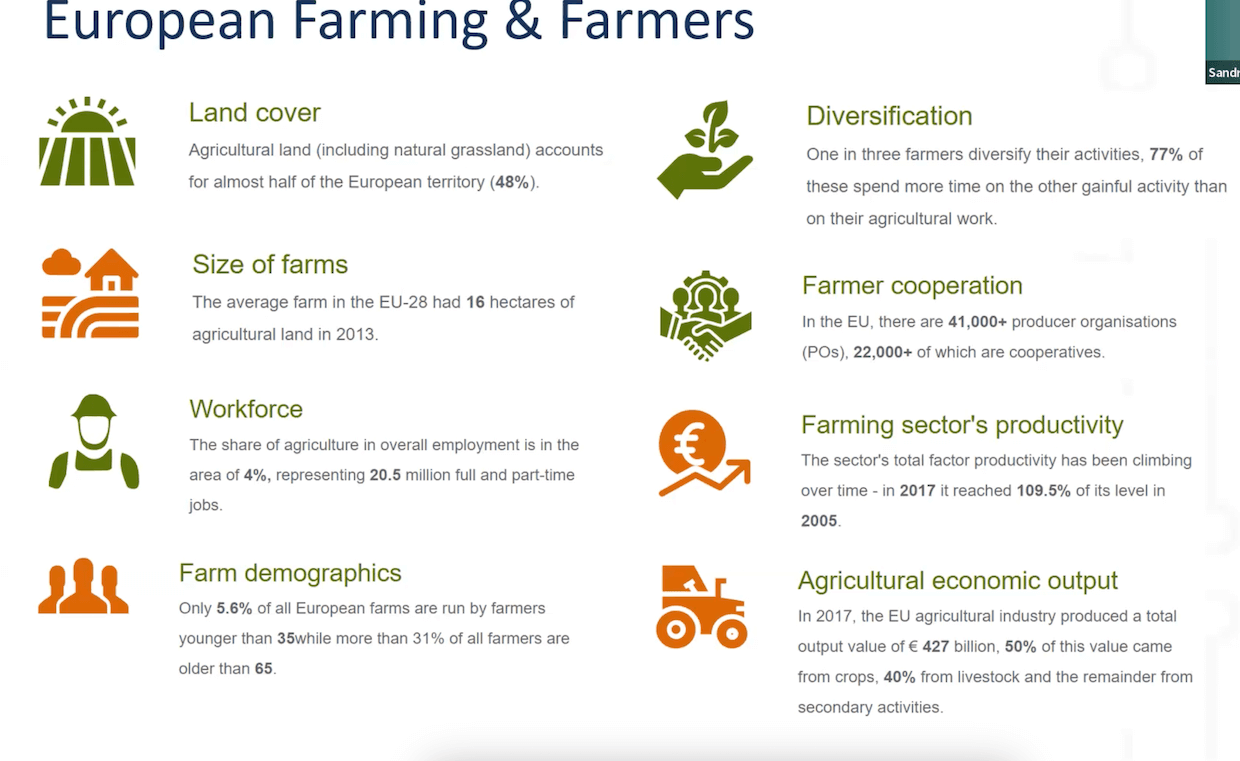

In this section of her lecture, Prof. Sandra Ricart provided a thorough examination of the structural and demographic characteristics of European agriculture, establishing a foundation for understanding the current crisis in the farming sector and its relationship with populist politics. She began by presenting an overarching picture of European agriculture today, emphasizing that while European farms continue to supply the essential public good of food production, their demographic base is in decline. One of the key concerns, Prof. Ricart explained, is the significant reduction in the number of young people entering the farming profession—a worrying trend that raises doubts about the future viability of agriculture across the continent.

This demographic challenge is not only contributing to the fragility of the sector but has also become a recurring theme in farmer protests and critiques of policy frameworks like the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Prof. Ricart highlighted that farming is no longer as attractive as other sectors to younger generations, who are drawn instead to professions perceived as more innovative or economically viable. The absence of generational renewal within farming communities threatens to exacerbate the structural weaknesses of European agriculture, an issue that populist movements have readily exploited.

Turning to structural characteristics, Prof. Ricart observed a striking duality in European agriculture: on the one hand, very small farms, and on the other, large-scale agribusinesses. This dual structure shapes debates around policy and representation. Small farmers, who often feel excluded from decision-making processes and inadequately represented in policy outcomes, have become increasingly vocal in their grievances—grievances that, as Dr. Ricart noted, form fertile ground for far-right political movements seeking to mobilize rural discontent.

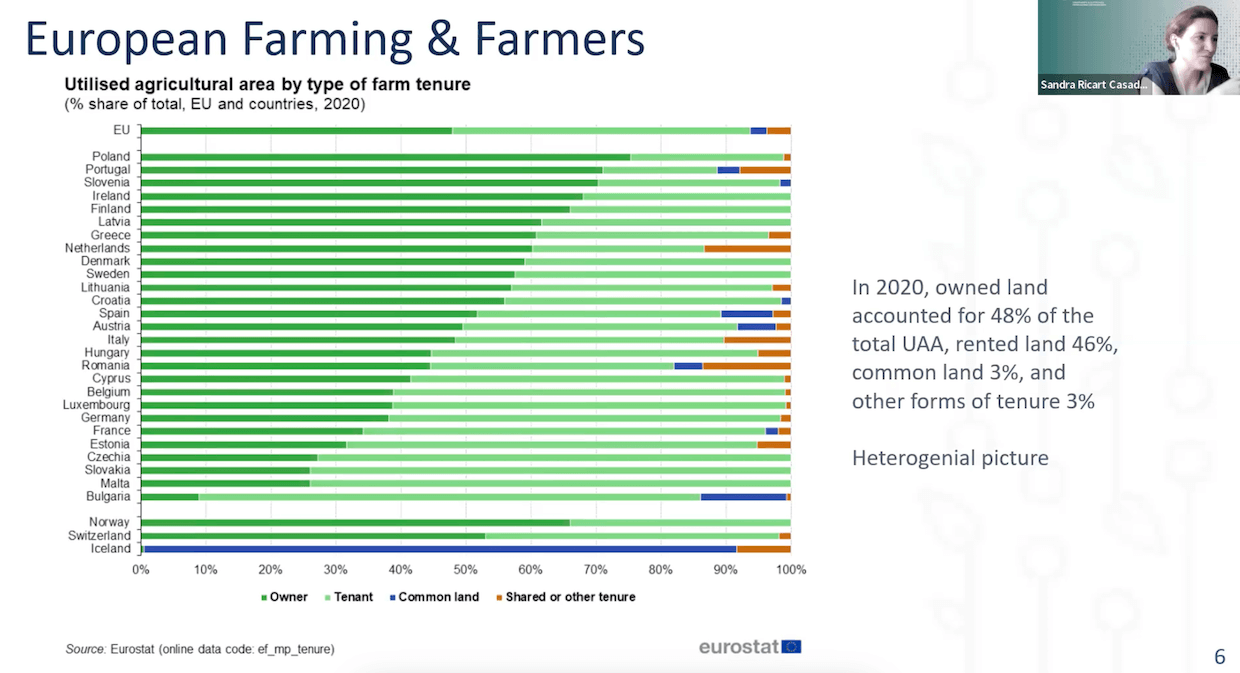

Land ownership patterns further complicate this picture. Prof. Ricart emphasized that ownership versus tenancy is a critical determinant of farmers’ capacity to plan for the future and adapt to challenges such as climate change. Farmers who own their land generally have more autonomy to invest in sustainable practices or infrastructure, while tenant farmers must navigate complex relationships with landlords, making long-term planning and adaptation more difficult. Access to land, and the sense of security it brings, is thus a central theme in both farmer protests and wider rural political discourse.

Geographically, Prof. Ricart provided a comparative overview of farming’s importance across European countries, noting that countries such as France, Spain, Italy, Germany, and Poland dominate agricultural production. Unsurprisingly, it is in these countries that farmers’ protests have been most intense and visible. However, she also noted that smaller agricultural producers such as Belgium have played outsized roles in protest dynamics, in part because of their political significance as hosts of EU institutions—a symbolically powerful site for expressing Europe-wide grievances.

Prof. Ricart drew attention to the uneven distribution of farming activity in both crop production and livestock rearing, noting that this structural diversity partly explains national differences in protest intensity and focus. For instance, she pointed out that livestock farming has been particularly vulnerable to recent regulatory pressures concerning animal welfare, further fueling discontent in sectors already under demographic and economic strain.

Another central theme in Prof. Ricart’s analysis was the economic precariousness of the farming sector. While agricultural productivity in some areas remains high, farm incomes across the EU have stagnated or declined over the past 15 years, despite increasing demands on farmers to comply with new environmental, health, and quality standards. This trend, she argued, is pushing many farmers toward poverty and fueling the perception that the sector is in structural crisis. Dr. Ricart noted that this growing economic pressure is also a focal point for populist messaging, with far-right parties seeking to position themselves as champions of “forgotten” rural communities whose economic contributions are undervalued and whose livelihoods are threatened.

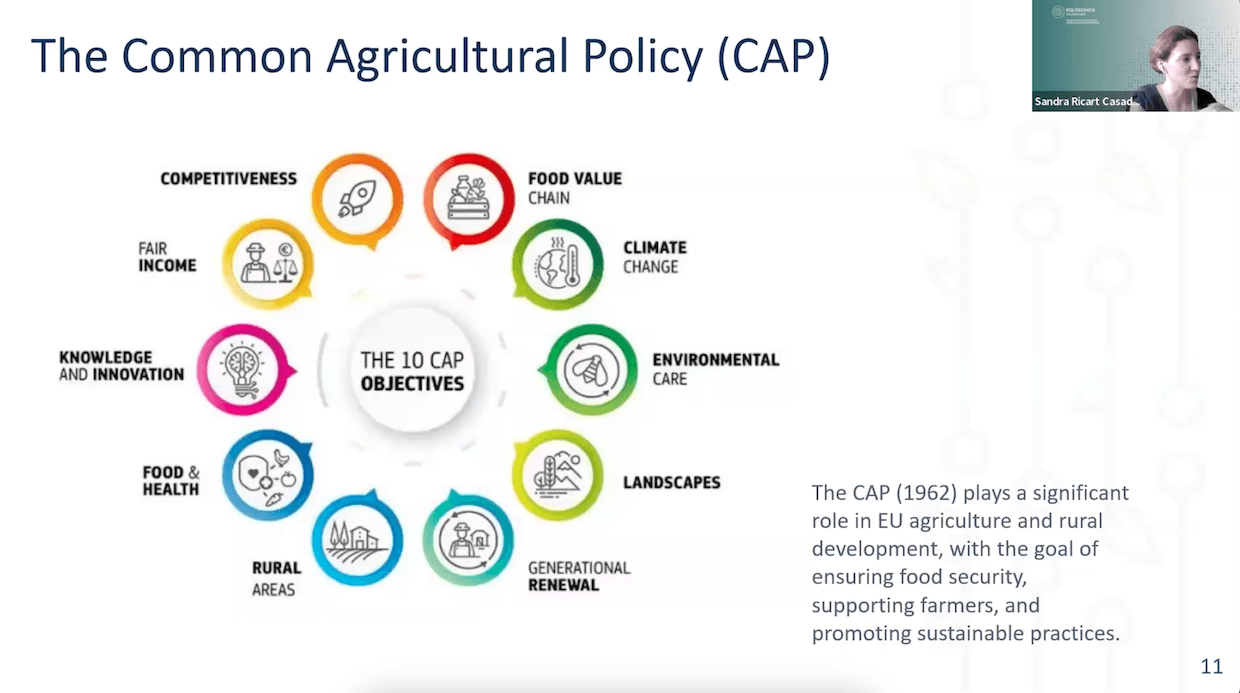

Prof. Ricart then turned to a discussion of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) itself, providing participants with a succinct history of this keystone of European agricultural governance. The CAP, she noted, is over sixty years old and reflects an evolving set of priorities, including ensuring fair incomes for farmers, guaranteeing food quality and security, and increasingly, delivering environmental public goods such as biodiversity protection and landscape conservation. Yet, despite this broadening policy remit, she emphasized that much of the farming community continues to view the CAP as insufficiently responsive to their day-to-day struggles and future uncertainties.

She detailed how the CAP operates through three principal instruments: direct payments to farmers, market regulation mechanisms to stabilize prices and ensure quality standards, and rural development measures aimed at supporting sustainable and resilient agricultural practices. While these instruments theoretically provide a safety net for farmers and a policy framework to navigate market volatility and environmental pressures, Prof. Ricart noted that many farmers feel excluded from the design of these instruments and find them too bureaucratic or insufficiently tailored to their realities.

Finally, Prof. Ricart encouraged participants to reflect on the broader societal role of agriculture. Beyond producing food, she argued, farmers maintain landscapes, provide ecosystem services, and sustain rural ways of life that are part of Europe’s cultural heritage. Yet these broader contributions, while rhetorically valued, are not always matched by policy support or financial compensation.

In sum, this section of Prof. Ricart’s lecture painted a complex portrait of European agriculture as a sector at once economically vital, socially significant, and deeply troubled. Demographic decline, structural dualities, insecure land tenure, uneven income trends, and rising regulatory demands all combine to create a sense of existential threat among farmers—a sentiment that far-right and populist movements have been quick to harness. Prof. Ricart’s analysis offered participants a critical foundation for understanding how these material and structural conditions form the backdrop against which agricultural grievances are expressed and politicized in contemporary Europe.

Climate Change Impacts and Farmer Perceptions

After discussing the demographic and structural features of the agricultural sector, Prof. Ricart shifted focus to how climate-related concerns, perceptions of fairness, and economic pressures are shaping farmer reactions across Europe—culminating in recent protests and increasing alignment with far-right narratives.

Prof. Ricart began by highlighting key findings from the latest Eurobarometer survey, which collects European citizens’ perceptions of agriculture and the CAP. She emphasized that across Europe, there is broad recognition among the public that farmers play a vital role in providing a common good: safe, reliable, and sustainable food production. Yet this recognition comes with expectations. Citizens increasingly call for farming that is not just productive but also healthy, safe, and environmentally sustainable. Prof. Ricart explained how this demand for responsibility intersects with the pressures farmers face today. While the farming sector remains foundational for European societies, farmers increasingly feel they are being asked to meet high standards without receiving sufficient support or understanding from policymakers and consumers.

This dynamic, Prof. Ricart noted, feeds directly into the tensions underlying farmer protests and far-right mobilization. The narrative of an “us versus them” divide—between farmers and urban consumers, between national farming sectors and EU-level regulators—has become central to both farmer grievances and far-right political messaging. Farmers are not only demanding fairer prices or simpler regulations; they are questioning the fairness of a system that expects sustainability but struggles to compensate the costs associated with these demands.

One critical source of tension has been the perceived destabilization of agricultural markets due to imports from outside the European Union. Prof. Ricart observed that many European farmers feel exposed to unfair competition from imports that may not meet the EU’s rigorous environmental, safety, or labor standards. Coupled with broader concerns over food security and living standards, these anxieties have animated recent protests and provided fertile ground for far-right groups eager to position themselves as defenders of national farming communities.

Prof. Ricart then introduced the European Green Deal (EGD) as a policy framework that, while ambitious, has intensified these debates. The Green Deal, launched in 2020, aims to make Europe climate-neutral by 2050, setting interim targets for 2030. Its requirements have direct implications for agriculture, from reducing pesticide and fertilizer use to expanding organic farming and ensuring sustainability throughout supply chains. Prof. Ricart acknowledged the policy’s laudable goals but underscored the dilemma it creates for farmers: many feel that the timeframes imposed are too short, the costs too high, and the support mechanisms insufficient.

For example, Prof. Ricart pointed out that transitioning to organic farming entails fundamental changes to farm structures and practices, requiring new equipment, training, and often a reorientation of entire business models. Likewise, reducing pesticide and fertilizer use demands investment in new technologies or methods, which smaller farms especially may struggle to afford. These requirements arrive amid other pressures such as fluctuating commodity prices, demographic decline within the farming population, and challenges related to land tenure, which collectively threaten the long-term viability of small and medium-scale farms.

The core of Prof. Ricart’s analysis centered on how climate change itself magnifies these difficulties. Drawing on survey data from research directly engaging with farmers, she illustrated how climate impacts—such as rising temperatures, more frequent and severe droughts, heatwaves, and increasingly erratic rainfall—are already deeply felt by farmers across Europe. These environmental stresses compound the pressures from policy reforms, making adaptation both urgent and costly.

Notably, farmers’ perceptions of climate change reflect a mix of acknowledgment and anxiety. Most farmers accept that climate change is happening and that it is affecting their livelihoods. However, their capacity to respond is constrained by the intersection of environmental change with market conditions, regulatory burdens, and infrastructural limitations. This complexity explains why climate-related grievances have become entangled with broader frustrations about agricultural policy and governance.

In concluding this section, Prof. Ricart emphasized that climate change acts as an overarching factor, reshaping every challenge farmers face and intensifying old grievances while generating new ones. While environmental sustainability is an essential goal, the pathways toward that goal must recognize the diversity and vulnerability of agricultural systems across Europe. For many farmers, the question is not whether to pursue sustainability but how to do so while maintaining livelihoods and ensuring intergenerational continuity in farming communities.

Prof. Ricart made clear that understanding farmer protests and far-right populist responses requires attention to this nexus of environmental pressures, policy demands, and lived economic realities. Climate change is not an abstract concern for European farmers; it is a daily challenge that intersects with perceptions of fairness, justice, and recognition—making it a central terrain on which political struggles over the future of European agriculture will continue to unfold.

Examining the Widespread Farmers’ Protests

Prof. Ricart also examined how the farmer protests that erupted across Europe in late 2023 and early 2024 reflected a deeper and widespread crisis in agricultural policy and governance. These protests, Prof. Ricart noted, were not isolated or confined to any single country or grievance; rather, they represented a growing pan-European tendency where farmers across national contexts expressed similar frustrations and demands. The protests became an important transnational phenomenon, with farmers mobilizing around shared grievances and converging symbolically in Belgium, home to European Union institutions, to amplify their voices at the continental level.

Prof. Ricart highlighted three core drivers motivating the protests: falling food prices, increasingly stringent environmental regulations, and a growing perception that European agricultural policy was failing to address national specificities. Low food prices, often a result of global market pressures and import competition, squeezed farm incomes, exacerbating rural economic insecurity. Simultaneously, farmers faced new and challenging environmental regulations associated with the EGD and climate action objectives. These regulations demanded significant changes in production methods, often imposing costs that smaller farmers in particular struggled to meet.

The third factor, Prof. Ricart emphasized, was a nationalist framing of grievances that far-right populist movements readily exploited. By portraying European Union policy as a detached elite imposition and emphasizing the loss of national sovereignty, populist actors framed the discontent in binary terms: a struggle between "us," the farmers and citizens, and "them," the distant European policymakers and foreign competitors. The far right’s message was that only national governments—not European-level institutions—could defend farmers’ interests, a rhetoric that found resonance among frustrated agricultural communities.

Prof. Ricart also pointed to widespread farmer criticism of the CAP, which has been revised repeatedly since its inception in 1962. Many protesters argued that successive CAP reforms had failed to resolve longstanding issues while introducing additional bureaucratic burdens. Farmers felt caught between contradictory pressures: on one hand, to modernize and adapt to environmental goals; on the other, to survive in a competitive market that undermined their income and livelihoods.

In countries like France, where agriculture has historically been a politically privileged sector, Prof. Ricart noted that many farmers nevertheless felt marginalized at the European level. This perceived disconnect between national pride in agriculture and EU-wide agricultural governance became a further source of frustration and mobilization. The protests, Prof. Ricart concluded, reflected not just sectoral discontent but broader tensions between rural communities and European integration, exacerbated by the politics of populism.

Farmers’ Protests and the Rise of Far-Right Populist Actors Across Europe

In her lecture, Prof. Ricart also explored how recent farmers’ protests across Europe intersect with the rise of far-right populist actors, revealing complex political dynamics. Prof. Ricart underscored that while farmers’ grievances are rooted in real economic, environmental, and policy challenges, the far right has increasingly sought to instrumentalize these frustrations to expand its influence.

She began by highlighting how the farmers’ protests that erupted across the continent in late 2023 and early 2024 were not isolated events, but part of a transnational pattern. Farmers in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and other countries took to the streets, expressing concerns over falling food prices, rising costs, burdensome environmental regulations, and trade competition. While these protests expressed legitimate anxieties about livelihoods and rural futures, Prof. Ricart pointed out that they have become fertile ground for far-right populist narratives.

One key theme Prof. Ricart identified was the way far-right actors strategically differentiated between national and supranational representations of farmers. In France, for instance, far-right politicians emphasized that while the French state historically recognized and honored its farmers, European-level governance failed to acknowledge their unique role and plight. This narrative enabled far-right movements to portray themselves as defenders of national agricultural traditions against what they framed as an out-of-touch European elite.

Prof. Ricart emphasized that this trend was not confined to France. In Germany, while farmers’ unions and associations initially led protests with non-partisan messages, far-right parties quickly appropriated these discourses, tailoring them to appeal to rural voters. These actors often moved faster than traditional political parties, repackaging farmers’ demands into simplified, emotive slogans, aimed at mobilizing disaffected segments of the rural population.

In Italy, Prof. Ricart observed similar patterns, citing protest slogans such as “We are farmers, not slaves” as emblematic of the populist rhetoric. Such messages resonated with farmers’ sense of marginalization, but also opened the door for far-right narratives that positioned themselves as authentic champions of “the people” against technocratic elites. Across these contexts, Prof. Ricart noted how the far right’s involvement blurred the boundaries between farmers’ legitimate protests and politicized mobilizations aimed at electoral gain.

A notable point in Prof. Ricart’s analysis was how far-right actors framed these protests as the “beginning” of a broader rural revolt. Farmers’ actions were reinterpreted as symbolic of a wider societal struggle, fueling a narrative of grievance that transcended agricultural policy and encompassed broader themes of national sovereignty, identity, and distrust of transnational governance structures. Prof. Ricart emphasized that this framing intensified the division between “us” (the nation’s people) and “them” (European bureaucrats and elites), reinforcing nationalist populist logics.

Prof. Ricart also addressed how environmental and climate change policies—particularly those associated with the EGD—became a focal point for far-right mobilization. She explained that climate-related regulations, such as pesticide and fertilizer restrictions or the promotion of organic farming, were recast by populist actors as evidence of elite detachment from the material realities of rural life. In this context, far-right rhetoric constructed a powerful image of embattled farmers struggling to comply with costly, unrealistic demands imposed from Brussels, appealing to a broad coalition of discontented rural and peri-urban voters.

Further, Prof. Ricart noted that the far right’s engagement with farmers’ protests coincided with the European Parliament elections, a crucial opportunity for these actors to expand their electoral base. By framing themselves as responsive to farmers’ frustrations—while traditional parties appeared slow or ambivalent—the far right strengthened its foothold in rural regions. In countries such as France, Italy, and parts of Eastern Europe, this alignment translated into electoral gains and a consolidation of populist influence over rural political discourse.

Toward the conclusion of this section, Prof. Ricart reflected on the broader implications of this intersection between protest and populism. She warned that while far-right parties appropriated farmers’ grievances to gain visibility and votes, their actual policy platforms offered few substantive solutions to address the underlying economic and environmental challenges facing agriculture. In contrast, she emphasized that farmers themselves were primarily concerned with ensuring the sustainability of their livelihoods and agricultural traditions, rather than endorsing a particular ideological agenda.

Ultimately, Prof. Ricart argued that this dynamic illustrates how populist politics can exploit genuine socio-economic discontent while offering simplistic narratives that obscure the structural complexities of agricultural transformation in an era of climate crisis and globalized markets. As farmers continue to grapple with these pressures, the interplay between their protests and far-right populist strategies will remain a critical area for further analysis and political reflection.

Conclusion

Prof. Sandra Ricart offered participants of the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025, a nuanced analysis of the evolving relationship between climate change, agriculture, and populist politics in Europe. Her presentation revealed that European farming communities today face a convergence of pressures: demographic decline, economic precarity, regulatory demands, and intensifying climate-related challenges. These stresses have not only shaped farmer perceptions and protests but have also provided fertile ground for far-right populist actors who seek to frame rural discontent in nationalist and anti-European terms.

Prof. Ricart emphasized that while farmers’ grievances are real and rooted in structural inequalities and policy shortcomings, the appropriation of these grievances by far-right movements raises important questions about the politicization of rural discontent. She underscored that populist narratives tend to simplify complex agricultural challenges, presenting an "us versus them" logic that pits national farmers and citizens against distant European elites and external competitors, while offering few substantive solutions for the sector’s long-term sustainability.

At the same time, Prof. Ricart acknowledged the legitimacy of farmers’ frustrations, particularly their concerns over falling incomes, generational decline, and a perceived disconnect between European policy frameworks and the lived realities of rural communities. Her analysis called for a more inclusive and responsive agricultural policy that better reflects farmers’ needs, supports adaptation to climate change, and ensures economic viability while promoting environmental sustainability.

Ultimately, Prof. Ricart concluded that the future of European agriculture will depend on addressing these multifaceted challenges without allowing populist actors to monopolize the narrative. Her lecture encouraged participants to think critically about how governance frameworks, political discourse, and climate adaptation strategies must evolve in tandem to protect both Europe’s rural communities and the democratic structures that underpin them.