While the global community often articulates refugee detention as a banner of humanitarian concern, escalating evidence from Libya and North African regions reveals a deeper systemic failure where stateless refugees and other displaced persons are being subjected to medical procedures and organ removal through coercion masked as border security and health screening. Across these detention zones, a shadow economy thrives thereby transforming stateless refugees into targets of extrajudicial biomedical intervention. This article uncovers the alarming rise of coerced organ extraction and exploitative medical practices presented as humanitarian care, introducing the concept biomedical sovereignty to expose the violent necropolitics at play. To build upon forensic data, survivor testimonies, and policy analysis, the following article calls for an urgent re-evaluation of international ethical obligations toward radically marginalized populations.

By Umavi Pagoda*

A 19-year-old Eritrean refugee is relocated from a detention center near Tripoli for what officials call a routine medical check-up. His departure marked the start of an absence that would never find closure as he became another unreturned face in a system that forgets too quickly. The following day, his belongings are returned to the dormitory with no explanation. His name is erased from records. His body is never found.

This incident is a fragment of a broader systematic pattern, one propagated across detention zones with troubling consistency in North Africa, where refugees are processed not only as asylum-seekers but as medical targets. While corridors of power continue to argue over the ethics and logistics of migration quotas and border security, a quieter atrocity is unfolding where the systematic medical exploitation of stateless persons, often unfolding into coerced organ removal. Within the ward where law disguises violence as care, silence kills quieter than bullets, outruns justice, and erases crimes before they are named. In extraction zones, silence enforced policy by design, not by accident.

Militias, Traffickers, and Medical Collusion

Since the fall of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, Libya represents a textbook case of post-revolutionary power vacuum, dominated by militia entrenchment, coercion by proxy, and smuggling networks. Moreover, in the absence of central governance, detention centers have evolved into profit-generating hubs for human trafficking, including a disturbing development: organ trade.

Strategic assessments by the Inter-Agency Coordination Group against Trafficking in Persons (ICAT) outline that trafficking in persons for the purpose of organ removal is recognized under the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol (Palermo Protocol) as a serious but hidden form of exploitation. Furthermore law-enforcement analysis by INTERPOL (2021) lays bare how criminal networks present in North and West Africa, which includes actors with medical links target vulnerable migrants and displaced populations for organ removal. Moreover, media investigation have further illustrated these risks, with platforms such as The Guardian (2024) bear witness to testimonies of migrants who were coerced into organ sales exposing the collusion between traffickers and medical staff.

Migrants and the displaced from sub-Saharan Africa, Syria, Bangladesh, and the Horn of Africa are frequently subjected to captivity under force along main transit routes through Agadez in Niger and eastern Sudan, with Libya positioned as Europe’s de facto checkpoint. In addition, these detention centers are often routinely run by militias and other non-state actors in alliance with traffickers and smugglers, under credible allegations of organ-trafficking risks and unease over possible complicity of medical personnel. Without independent oversight or any mechanism for accountability, these facilities—designed for secrecy—function as black boxes

From Rumor to Routine: Coerced Organ Removal Across Migration Routes

What was once a rumor is now routinized —measured in spreadsheets, hidden in budgets, and carved into bodies. In recent years, humanitarian workers and forensic specialists have uncovered disturbing patterns of disappearances and allegations of coerced medical procedures—making clear that the undocumented body, once erased by the state, is reintroduced into systems of value as currency, commodity, and collateral. Illicit transplant surgeries have been documented in multiple countries through police operations and court cases, even as UNODC’s Assessment Toolkit (2015) characterizes trafficking for organ removal as a hidden, under-reported crime whose true scale remains unknown.

From capitals to courtroom, global monitors have begun documenting the horror. The July 2024 IMO-UNHCR Mixed Migration Centre Report interviewed migrants, revealing patterns of detainees taken for blood testing and disappearing shortly afterward. Survivors report post-procedural states marked by disorientation, physical pain, and memory loss—reflecting a troubling loss of bodily agency under conditions where medical procedures are imposed rather than chosen.

In July 2023, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) warned of deepening shadows over Libya, where layers of entrenched crimes have become almost invisible to international oversight: human trafficking, arbitrary detention, enforced disappearances, and the systematic torture of migrants and refugees—many lacking recognized nationality and thus classified as stateless under international law (OHCHR, 2023).

Statelessness strips individuals of legal protection, leaving them defenseless against exploitation, including illicit organ removal. This risk is echoed in multiple reports, including a study led by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and the Mixed Migration Center (July 2024), which documents the experiences of refugees and migrants—many likely stateless—describing non-consensual organ removal along migration routes to the Mediterranean (Reuters, 2024). Witness journalism documents the experiences of 43 individuals from Sudan, South Sudan, and Eritrea—many of whom are absent from any civil registry—who sold a kidney under coercion, underscoring how displacement and the absence of state protection leave individuals acutely vulnerable to the most extreme forms of trafficking (The Guardian, 2024).

Borders Beneath the Skin

In the shadows of ports, prisons, and refugee camps, the passport has been reduced to flesh, and the border is inscribed in blood. The trail starts in Tripoli, where the Mixed Migration Centre’s Everyone’s Prey briefing (July 2019) reports patterns of kidnapping and extortion of migrants in Libya’s detention industry. Moreover structural analysis such as the OSCE study on trafficking for organ removal coupled with the ICAT policy brief highlight how displacement and detention centers formulate systematic flaws that can be preyed upon by trafficking networks.

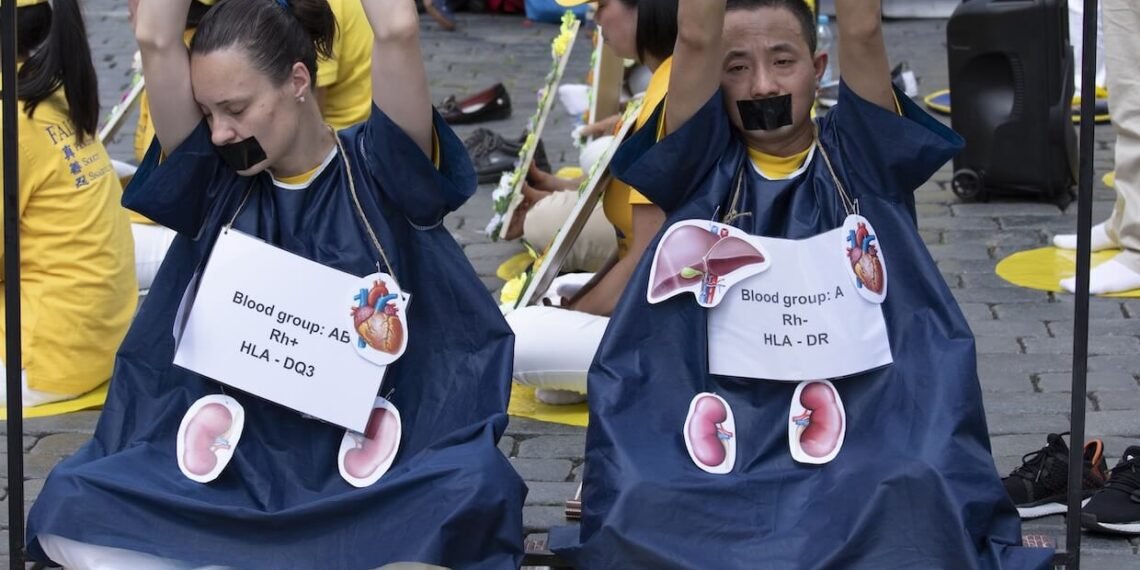

Law-enforcement alarm remains unambiguous in INTERPOL’s 2021 assessment which documents that organized crime groups based in North and West Africa prey on migrants and other displaced persons for coerced organ removal often shadowed by medical collusion. The UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons (2022) observes that such trafficking persists in shadows, though it remains rare when in comparison to sexual or labor exploitations. Diesel generators hum into the darkness, fueling flickering lights over neglected wounds. The hum echoes east, into Xinjiang’s Dabancheng complex. Moreover, survivors bore witness before the Uyghur Tribunal revealing that they were subjected to blood draws, tissue typing, and ultrasound scans stripped of consent. In forensic retrospect, these procedures suggest a system where the border no longer ends at territory but continues beneath the skin.

This brutality is mirrored in the testimonies of countless individuals whose voices bleed through silence. On August 10, 2024, The Diplomat reported the public testimony of Cheng Pei Ming, described as the first known survivor of forced organ harvesting in China to speak openly. Cheng remains a crucial witness to an ongoing, state-directed system of coerced organ extraction — a campaign that the independent China Tribunal (2019) concluded was organized and carried out by the Chinese Communist Party, beyond reasonable doubt.

However, Beijing rejects any acknowledgement of state-directed coerced organ harvesting, particularly when involving prisoners of conscience. The official position maintains a stance of denial, asserting that the practice of using organs from executed prisoners was halted in 2015.

Bodies as Evidence: Testimonies of Coerced Organ Harvesting and the Global Shadow Trade

Policy is prose, while the body is evidence. Cheng’s testimony stands as a singular, rare first-person account. He recounts: “They said that I had to undergo an operation, but I firmly refused. They held me down and gave me an injection, and I quickly lost consciousness. When I woke up, I was still in the hospital and felt terrible pain in my side.” Refusal. Confinement. Injection. Blackout. Waking up shackled, with an IV taped to his foot, a drainage tube in his chest, oxygen tubes in his nose, and a thirty-five-centimeter incision. “There was a tube with bloody liquid coming from under the bandaging that was on my side,” he adds, as documented in the ETAC media release.

Additionally, The Diplomat reports that Xinjiang authorities plan to establish six new organ transplant centers despite the region’s strikingly low official voluntary donation rate — a figure widely disputed by human rights organizations.

While the East provides a witness, the South offers a case file. Described by authorities as Egypt’s largest organ-trafficking case to date, the December 2016 raids targeted 10 medical centers, resulting in 37 convictions in 2018. Among those arrested were several medical professionals, and authorities reported the recovery of millions in assets.

Victims, including Sudanese asylum seekers, recounted waking from anesthesia to find fresh surgical dressings, visible scars, and the absence of a kidney. Within North and West Africa, INTERPOL (2021) assessment states that organized crime groups frequently prey on migrants and refugees, often under the guise of “altruistic donations” and frequently shadowed by medical-sector complicity.

Additionally, some clinics are reported to perform both legal and illegal procedures simultaneously. However, weak reporting mechanisms and fragmented medical registries allow the illicit trade to thrive in the shadows.

Across borders, the UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons (2022) records that trafficking for organ removal remains a statistical rarity in detected cases and is chronically under-reported. Furthermore, the only treaty directly addressing organ trafficking, the Council of Europe Convention against Trafficking in Human Organs (CETS No. 216), continues to struggle with limited ratification.

In a parallel theatre, in the Sinai, Eritrean captives have been kidnapped and tortured for ransom. In some cases, they were killed when payments failed; several testimonies also allege organ removal—a practice all too familiar—although rights reporting primarily emphasizes the ransom-torture economy. Yet the trail does not end in Sinai.

In April 2025, the trail led to Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, where the body of 19-year-old Beatrice Warguru Mwangi was returned to Kenya. What was returned was missing a stomach, eyes, and reproductive organs; her neck was almost severed. “How is this my daughter? Her body was empty. No stomach inside. Her breasts were cut …,” her mother testified to Migrants-Rights.org. The post-mortem examination in Nairobi further documented signs of strangulation, dehydration, and prolonged starvation. Despite petitions, the case remains unanswered—with no formal inquiry, no published findings, and no transparent remedial steps. One body speaking for many, her body stands as a summons to states to intervene.

Surgical Sovereignty and Stateless Bodies

This cross-national pattern highlights how, in detention and transit zones, where oversight falters and legal authority is often liminal, protection gaps open like unhealed wounds. The absence of identification papers renders human beings harder to see and easier to exploit. These are not isolated anomalies; rather, they expose a deeper implementation gap: the 1954 Convention and the Palermo Protocol—while widely ratified—remain unevenly enforced in practice, repeatedly failing at the stage of implementation. As a result, data remain under-reported, justice remains selective, and access to remedies often depends on documentation and financial means.

At the core of this atrocity lies a collapse of medical integrity—a reversal of the healer’s oath. Clinical spaces become theatres of harm, with ethics dissolved into silence. The obligation remains clear: voluntary, informed consent and the absence of financial gain are fundamental norms, and physicians must not participate in abuse, including in detention settings.

Yet, in documented cases, detainees have repeatedly been subjected to medical procedures without consent and denied proper care—from coercive interventions behind the closed gates of Libyan detention centers to intrusive medical testing in Xinjiang—while criminal networks exploit these systemic gaps. In such contexts, human bodies are treated as inventory rather than as patients.

This dynamic aligns with the concept of surgical sovereignty—the ability of non-state and state-adjacent actors to exert coercive control and extract biological value from stateless and displaced persons.

The concept of surgical sovereignty refers to the ability to use medical infrastructure by non-state actors to exert coercive control and exploit the biological value of stateless persons — those “not considered as nationals by any State under the operation of its law,” as defined in the 1954 Convention Art.1 (1). In these spaces, procedures continue to occur without voluntary, informed consent or credible oversight, reversing medicine’s role from care to control. The framework aligns with biopolitics but specifically isolates the role of medical systems. Moreover, the Palermo Protocol defines trafficking to include exploitation for the removal of organs, even as its implementation remains weak.

In February 2025, authorities in southeast Libya uncovered two migrant mass graves, freed 76 captives, and made three arrests linked to suspected trafficking sites. The following month, Sudanese refugees reported accounts of starvation, rape, slavery — and, in some testimonies, organ harvesting — along migration routes to the north. From a forensic perspective, such conditions cannot sustain lawful surgery: there is no anesthesia, no sterile field, and no consent, as required under the WHO Guiding Principles. Moreover under international law, such death and disappearances demand the recognition of right to life and a duty to reinvestigate as outlined in International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 6 and the Human Rights Committee’s General Comment No. 36. An individual’s right to health requires consent, documentation and oversight under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Article 12 and CESR General Comment No.14. Failure to keep records or examine remains may be treated as violations.

Although abuses remain widespread and often under-investigated, the law frequently erodes into silence. This is compounded by the absence of an effective accountability mechanism to enforce WHO health standards in conflict settings and detention sites. Current mandates also struggle to reach non-state actors who control many of these camps. As of 2025, the international response has been both limited and late.

Cut in Silence: The Cost of Global Inaction

This silence echoes earlier failures and undermines the very foundations of the post-war settlement the world claims to uphold. The 1947 Nuremberg Code declared voluntary, informed consent to be non-negotiable — even in times of conflict. Yet in modern-day Libya, while the principle is acknowledged in theory, it remains absent in practice.

What fails in implementation locally is often underwritten by decisions made in Europe. Amnesty International’s Europe’s Gatekeeper (2015) reported that EU funding and equipment to Libya’s coastguard and detention systems have given cover to abuses against migrants: arbitrary detention, torture, extortion. Moreover, UN reporting and rights groups have revealed a grim pattern: people returned to Libya vanish into detention centers or unregistered sites. Many then become effectively untraceable. Furthermore, The Global Protection Cluster cautions that Libya’s legal ambiguity between migrants, asylum seekers, refugees, and trafficking survivors becomes a structural barrier to protection and remedies. Médecins Sans Frontières has reported overcrowding and the lack of adequate care: conditions that are irreconcilable with the very principles of medical care and a blatant disregard for the laws of human dignity.

Yet beneath the reports and the evidence, a deeper question is left unanswered. What happens to the body unclaimed by nation, unnamed by law, unacknowledged by history? What happens to a life that holds no legal weight, does its loss echo anywhere? In these spaces, the lack of prosecution remains as the infrastructure of impunity.

Breaking the Silence on Hidden Atrocities

This article does not claim to resolve the failures of states. However, it demands that the silence surrounding medical atrocities be dismantled. As the world increasingly governs bodies before protecting them, a pressing question persists: how long until the promise of healing conceals the reality of extraction?

When the refugee body is no longer seen as a body in need but one that is policed, processed, and politicised, the surgeon’s scalpel — once an instrument of care — becomes a tool of control. These atrocities are not merely the actions of complicit individuals; they are the outcome of systemic structures that strip the stateless and the dispossessed of their humanity.

Once, the international community drew a line after gas seared lungs. Today, the responsibility falls on governments, international bodies, and all who claim moral authority to draw a new line — for those cut in silence — and to outlaw surgical violence against the voiceless. If we remember only the suffering but not the perpetrators, we bury the crime beside the victim.

Will those who once enforced accountability now hold states, militias, and complicit actors responsible for the scalpel used without consent — or will silence remain the price of statelessness? If the world outlawed gas, will it also outlaw surgical violence, or will the voiceless continue to pay the cost of inaction?

(*) Umavi Pagoda is a UK-based A-level student studying Politics, Chemistry, Biology, and Physics, with a focus on the intersection of medical ethics, human rights, and international law. Their work in international debate and policy stimulation has been recognized at multiple high-level Model United Nations conferences Worldwide. Email: pagodaumavi41@gmail.com

One Response

Excellent evidence based Analysis of a international organ extraction crime syndicate drawing attention of global community leaders