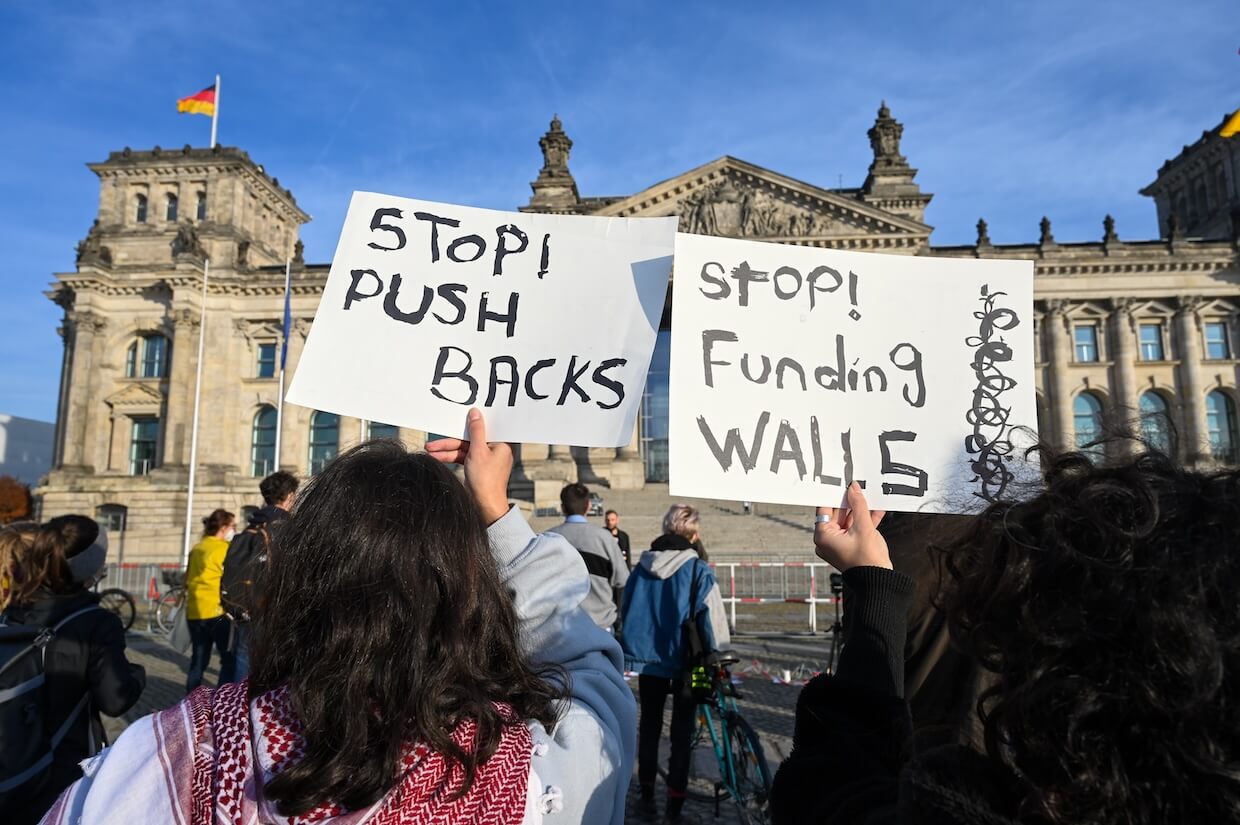

The EU’s human rights commitments are weakening as populist movements push restrictive migration policies, warns Dr. Ellen Desmet, Associate Professor of Migration Law at Ghent University. She describes a growing disregard for human rights, stating, “We are witnessing blatant human rights violations that are only increasing.” A 2024 report documented over 120,000 pushbacks at EU borders, violating non-refoulement by forcibly returning asylum seekers without assessing their protection needs. “Some EU countries have even legalized these pushbacks,” Desmet cautions, while the European Commission hesitates to act. She also points to far-right rhetoric shaping restrictive policies, with mainstream parties following suit. Meanwhile, according to Dr. Desmet, Belgium’s new government threatens judicial independence and tightens asylum rules, further escalating human rights concerns.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

The European Union’s commitment to human rights and asylum protections is under increasing strain as populist movements push for restrictive migration policies. Dr. Ellen Desmet, an Associate Professor of Migration Law at Ghent University, highlights this deterioration in a compelling interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). She provides an evidence-based assessment of how EU member states are violating fundamental principles of international refugee law, including the principle of non-refoulement.

According to Dr. Desmet, while "lip service is still paid to human rights on paper, in practice, we are witnessing blatant human rights violations that are only increasing." She points to a 2024 report by a Belgian coalition of NGOs, which documented over 120,000 pushbacks at EU external borders. These pushbacks, often occurring in Greece and other key entry points, involve forcibly returning people without assessing their need for protection—a direct violation of non-refoulement, which prohibits states from deporting individuals to places where they risk torture, persecution, or threats to their life and dignity. Disturbingly, some EU states have even enacted laws to legalize these pushbacks, while institutions like the European Commission remain reluctant to take action against these clear breaches of international law.

Beyond border policies, Dr. Desmet emphasizes a broader deterioration in the rights of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. She warns that European states are increasingly treating migrants as security threats, with a growing trend of externalizing migration policies—a tactic designed to shift asylum responsibilities away from the EU. This is particularly evident in Belgium’s recent policy shifts, where the new coalition government has adopted a more restrictive approach. "We see worrying developments from a rule-of-law perspective," she explains, referring to how judicial rulings on asylum reception have been ignored and how judicial independence is now under threat.

Dr. Desmet also discusses how far-right movements and mainstream political parties alike are fueling anti-migration policies by framing migration as a "crisis." This has led to ‘a race to the bottom’, where governments are tightening asylum laws to outmaneuver populist opponents. Policies once considered extreme are now becoming mainstream, further undermining human rights and democratic principles.

In this interview, Dr. Ellen Desmet provides a critical analysis of how legal frameworks, political rhetoric, and migration policies intersect, shedding light on one of Europe’s most pressing human rights challenges.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Dr. Ellen Desmet with some edits.

A Decline in the Rights of Migrants, Asylum Seekers, and Refugees Across Europe

Professor Desmet, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: There is a great deal of information, speculation, and conspiracy theories surrounding migration in Europe. Could you provide an evidence-based overview of the current migration landscape, particularly regarding refugees and asylum seekers from a human rights perspective?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: That’s a very broad question to start with. On the one hand, what we see, and what we also learn from sociological research, is that the flows or the number of people forcibly fleeing their country fluctuate, driven by wars, conflicts, and other factors. On the other hand, if you look at the current migration landscape from a human rights perspective, we see a deterioration in the rights of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees, who are increasingly being treated as suspects. There is also a growing tendency towards the externalization of migration policies, where European countries seek to prevent migrants and refugees from even reaching EU borders. This is because, once they arrive at EU borders, EU Member States become responsible for assessing their applications for international protection. To avoid this responsibility, efforts are made to externalize asylum procedures.

This trend is evidenced by agreements signed with various countries, such as Mauritania, among others. Additionally, last year, the New Pact on Migration and Asylum was adopted, introducing ten new legislative instruments that are currently in the process of being implemented. Member States are required to enforce these measures by the summer of 2026.

However, even within these legislative instruments—intended to create a more common European asylum system—we observe a reduction in the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. There is now greater emphasis on the duty of cooperation for asylum seekers. For example, if they come from a country with a low recognition rate, they will be automatically placed in a border procedure. This raises concerns, including questions about access to legal assistance.

Overall, at the EU level, both in legislation and implementation, as well as at the national level within Member States, we see a decline in respect for the human rights of migrants—not only in legal frameworks but also in policies and enforcement.

What role does the framing of migration as a ‘crisis’ play in fueling racist narratives in Belgium and across Europe?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: Previous research and arguments from other colleagues suggest that when migration is framed as a key issue in elections, and its salience increases, as we see now across Europe, it benefits populist anti-immigration parties. By making immigration a central political theme, it actually leads to anti-immigration parties gaining more votes.

Another consequence of this framing and the problematization of migration as a crisis is that it influences mainstream political parties to adopt or co-opt anti-immigration legislative and policy proposals from the extreme right. As a result, policies that diminish the human rights of migrants are increasingly being incorporated and implemented by so-called mainstream political parties.

Restrictive Migration Policies and Far-Right Rhetoric Reinforce Each Other

In recent years, European countries and the EU have undergone significant shifts in their refugee and asylum policies, from Merkel’s Willkommenskultur to increasing restrictions under more recent governments. How do you see these policy changes influencing public discourse and the political success of far-right parties like Vlaams Belang in Belgium and AfD in Germany?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: I think it’s somewhat of an interaction. On the one hand, these policy changes stem from shifts in political discourse. On the other hand, these policy changes may further fuel the political success of far-right parties, especially because the policy proposals of these parties are increasingly being adopted and implemented by mainstream political parties.

How has the rise of right-wing populism in Europe, particularly in Belgium, shaped national policies on migration and asylum seekers?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: Vlaams Belang, the far-right populist party, previously had what they called the "70 Points Plan." Now, we have a new federal government with a new coalition agreement being presented. In the coalition agreement, many of these proposals have already shifted towards restrictive measures, such as investing in the externalization of migration and halting resettlement until the reception crisis is resolved.

We also see worrying developments from a rule-of-law perspective. Under the previous government, many judicial rulings related to the reception crisis were simply ignored by the executive branch. For example, there were there were thousands of judgments requiring the government to provide material reception conditions for asylum seekers, yet these were disregarded.

Now, in the current coalition agreement, there are even more concerning proposals. One example is that the Council for Alien Law Litigation, which is the appeal tribunal for asylum and migration cases in Belgium, would see a change in how its judges are appointed. Instead of being nominated for life, as is standard to ensure judicial independence, the proposal suggests a renewable five-year term, which could put judicial independence under pressure.

So, my interpretation is that the rise of right-wing populism has contributed to more restrictive migration policies, as reflected in the current government agreements in Belgium.

EU Countries Undermine Non-Refoulement with Indiscriminate Pushbacks

The EU member states have legal obligations under international refugee law but rising populist sentiments and electoral pressures often push governments to tighten migration policies. How do you see this tension evolving, and what role can legal scholars and human rights advocates play in ensuring the protection of asylum seekers?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: I think we are witnessing a race to the bottom among EU Member States, where countries, following the example of Denmark and the Netherlands, and now Belgium, are striving to implement the strictest asylum and migration policies ever, as they have announced.

Here, I believe it is important to make a distinction. On the one hand, some rules can be tightened within legal boundaries. For example, under EU law, the Family Reunification Directive currently provides some legal flexibility, allowing for certain restrictions while remaining within the framework of EU law and human rights. This is explicitly mentioned in Belgium’s new government agreement, where it is stated that authorities will explore how far they can go in making migration, family reunification, and asylum rules as restrictive as possible within the limits allowed by existing legal frameworks.

On the other hand, while lip service is still paid to human rights on paper, in practice, we are witnessing blatant human rights violations that are only increasing. A recent report issued by the Belgian coalition of NGOs, in collaboration with nine other organizations, documented over 120,000 pushbacks at the EU’s external borders in 2024. These pushbacks involve people being forcibly returned without individual assessment of their need for protection, which is a clear violation of the principle of non-refoulement—the rule that prohibits sending people back to a place where they risk torture, persecution, or threats to their life and dignity.

These pushbacks are occurring at external borders such as Greece, and some countries have even enacted laws to legalize them. However, the European Commission and other institutions remain reluctant to act against these clear violations of international law.

As legal scholars and human rights advocates, our role is to inform the public about the current state of the law, highlighting where legal flexibility exists within the system, but also calling out policies that clearly violate the rule of law and fundamental human rights. For instance, the recent proposals concerning the Council for Alien Law Litigation, where judicial appointments would become temporary rather than lifetime positions, pose a serious threat to judicial independence. It is essential to emphasize these issues and raise awareness about the legal safeguards that should be in place.

By sharing knowledge about the rule of law, explaining what is happening, and informing people about the legal protections that should be upheld, we must do our part to contribute to the protection of asylum seekers and the integrity of legal systems.

Human Rights Obligations Are Being Set Aside for Political Convenience

In what ways have European states, in particular Belgium, balanced human rights obligations towards migrants with increasing domestic political pressure from populist movements?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: I think that today we see that human rights obligations tend to be ignored. As I previously mentioned regarding the reception crisis, which has lasted for two and a half years in Belgium, single adult men are being forced to sleep on the streets, even after being recognized as refugees. Due to Belgium’s ongoing housing crisis, many people do not have access to decent accommodation.

Previously, I believe it would have been unacceptable and concerning from a rule of law perspective for even one court ruling to be ignored. However, today, human rights obligations related to the provision of reception seem to be set aside under the argument that it is not feasible practically or politically. Sometimes, these obligations are not fulfilled out of fear that doing so might benefit populist movements. I believe that the balance between upholding human rights and responding to political pressures needs to be reaffirmed.

Your research discusses civil society’s role in resisting restrictive migration policies. How effective has civil society been in countering populist-driven migration policies in Belgium?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: I think the assessment is mixed. Under various previous governments, particularly during the 2014–2019 legislative period, when the Secretary of State for Asylum and Migration was controlled by the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), there was very little space for civil society to be consulted before legislative proposals were introduced. Many laws were passed without meaningful negotiation or consultation, and a significant number of these legislative proposals raised concerns from a human rights, migrant, and refugee rights perspective.

When the concerns of civil society organizations are not taken into account before the adoption of legislation, their only remaining option is to challenge these laws through legal appeals, such as filing cases with the Council of State or the Constitutional Court. Over the past years, civil society actors in Belgium have been vocal and active in bringing contested aspects of new migration and refugee policies before these higher courts. However, this judicial approach requires substantial human and financial resources, placing significant pressure on civil society organizations, as they must engage in lengthy legal battles to challenge problematic legislation.

As for the courts’ responses, the reactions have been mixed. In some cases, higher courts, including the Council of State and the Constitutional Court, have intervened to halt the most extreme or concerning policies. For example, during the 2014–2019 coalition, a quota was imposed on the number of asylum applications that could be submitted per day in Belgium. The Council of State overturned this measure, ruling that it clearly violated higher legal obligations. However, on other issues, the courts have taken a more minimalist approach, refraining from stronger interpretations of human rights protections. I think civil society organizations have been active in bringing cases to court to challenge new legislation. The courts have overturned some measures, but definitely not all.

The Global Compact for Migration Sparked Controversy but Had Little Legal Impact

How have international legal frameworks, such as the Global Compact for Migration, influenced migration policies in countries with strong far-right movements?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: I think it’s interesting to see how, seven years ago, all the talk was about the Global Compact for Migration, which in Belgium even led to the fall of the government when the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) left the coalition government over the Marrakesh Pact, as it was called. The concern at the time was that it would create new obligations for member states, despite the fact that the Global Compact for Migration explicitly stated that it was merely a restatement of existing obligations, was non-binding, and did not introduce any new legal commitments. The fact that a populist party left the federal government over a non-binding political instrument was a unique event in Belgium’s constitutional history, highlighting once again the political sensitivity of migration issues.

As for the actual impact, despite the initial controversy, the practical influence of the Global Compact for Migration has been quite limited. A first analysis of judgments before the Council for Alien Law Litigation, conducted a few years ago, showed no significant legal or judicial impact of the Global Compact for Migration in the Council’s case law.

So, while its adoption sparked significant debate and skepticism among anti-migration and populist parties, in practice, the Global Compact for Migration, as a non-binding political instrument, has not had a strong legal impact on national policies. Instead, I believe that the New Pact on Asylum and Migration from the European Union is likely to have a greater effect, as it consists of binding regulations that EU Member States are legally required to comply with and implement.

Given the growing influence of far-right politics across Europe, do you believe the EU and big players in EU politics can sustain a balanced asylum system that upholds human rights while addressing public concerns? What policy changes would you recommend creating a more sustainable and inclusive approach to migration and integration?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: That’s a very big question, but it’s not hard to answer. I think a lot of public concerns are not based on empirical knowledge of how migration actually works, including the fact that a certain level of migration is necessary for society. I believe it is also a matter of political will and political courage to recognize that migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers are human beings who are entitled to the same human rights as everyone else. It is in the best interest of society to facilitate family reunification, rather than making it overly restrictive, because such restrictions negatively impact the integration trajectories of refugees.

We recently completed a four-year research project on the integration trajectories of refugee families in Flanders and Belgium. Our policy recommendations emphasize the need for greater alignment and interaction between different policy domains, such as access to employment, education, and social services. Currently, too much emphasis is placed on Dutch language proficiency, which may actually hinder a smoother integration process.

Another issue lies in Belgium’s complex federal structure, where there is a disconnect between different levels of governance. For instance, at the federal level, the government is responsible for the reception of asylum seekers, but once refugees are recognized, access to housing falls under Flemish jurisdiction. This creates a gap, as no single government agency is explicitly responsible for ensuring that refugees obtain decent accommodation.

Additionally, there is a trend toward restricting social rights for refugees and migrants, which arguably hinders successful integration into society. In the federal government agreement, we often see contradictory approaches—on the one hand, migration policies focus on restricting family reunification, making it difficult for individuals to live with their families. On the other hand, in other policy areas, the government emphasizes the family as the cornerstone of society. These inconsistencies should be addressed by developing a more unified and coherent approach to migration and integration policies.

Belgium’s New Migration Policies Threaten Judicial Independence and Human Rights

How do you assess the new Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever’s government policies and proposals on immigration from a human rights perspective?

Dr. Ellen Desmet: I already touched upon some of the more concerning proposals. From a rule of law perspective, the measures concerning the Council for Alien Law Litigation are particularly troubling. Recently, some colleagues in human rights, constitutional law, and migration issued an opinion piece challenging these measures, as they risk undermining the independence and impartiality of the Council.

Beyond this, judicial independence is being threatened in other areas as well. The Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, which is currently an independent institution, is also at risk. The government agreement explicitly states that more people should receive subsidiary protection instead of refugee status, and there are plans to merge the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons with the Immigration Office into one large migration service. This proposal is problematic because, in Belgium, applications for international protection have traditionally been assessed independently by the Commissioner General, rather than by an Immigration Department, which falls under the direct authority of the Secretary of State or the Minister for Migration and Asylum. This independence is now being jeopardized through institutional restructuring and direct policy influence, which raises serious concerns.

Furthermore, Belgium appears to be following Germany’s approach by granting more subsidiary protection while simultaneously restricting family reunification rights for those under this status. Currently, EU law (the Family Reunification Directive) grants more favorable rights to refugees than to those with subsidiary protection. The Belgian government intends to increase subsidiary protection numbers while extending the waiting period and tightening family reunification rules for this group, effectively limiting their rights.

Additionally, another worrying development is the government’s decision to halt resettlement programs as long as the reception crisis persists. Resettlement is the only safe and legal pathway for asylum seekers to enter Belgium and putting it on hold further restricts access to protection.

Other proposals include increasing the duty of cooperation for asylum seekers, which could involve automatic monitoring of their social media accounts, such as Facebook. These measures, along with other restrictive policies, raise serious human rights and rule of law concerns. Overall, the new coalition government’s agreement places significant pressure on the rights of migrants and asylum seekers, making their situation increasingly precarious.