Dr. Heidi Hart’s lecture illuminated the provocative intersection of art, activism, and climate trauma. Through an interdisciplinary lens, she explored why climate activists increasingly target iconic artworks in museums as sites of performative protest, interpreting these acts not as mere vandalism but as symbolic disruptions challenging elitist cultural values amid ecological crisis. Drawing on frameworks from populism studies, art history, and affect theory, Dr. Hart examined how these interventions reflect a passionate response to climate grief and injustice. Her analysis underscored the importance of understanding such protests within broader debates on decolonization, posthumanism, and collective responsibility, encouraging participants to view artistic destruction as both a critique of cultural complacency and a call for ecological transformation.

Reported by ECPS Staff

On the third day of the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025—titled “Populism and Climate Change: Understanding What Is at Stake and Crafting Policy Suggestions for Stakeholders”—took place online from July 7–11, 2025, participants were treated to a rich and thought-provoking lecture by Dr. Heidi Hart, who offered an interdisciplinary perspective on a particularly provocative theme: the intersection of art vandalism, populist performance, and climate trauma.

Dr. Hart is an arts scholar, curator, and practitioner with a deep commitment to exploring the affective dimensions of ecological crisis through cultural forms. She is based between Copenhagen and North Carolina and holds a Ph.D. in German Studies from Duke University (2016). Her scholarly trajectory spans environmental humanities, climate grief, sound and music in ecological narratives, and the artistic aesthetics of destruction. Among her major works is the recently published monograph Climate Thanatology, which examines artistic engagements with death, loss, and creative transformation in the shadow of climate collapse. Her current research project, Instruments of Repair—supported by the Craftford Foundation—extends this inquiry into the ecological afterlives of musical instruments, analyzing how materials and sound objects decay, renew, and reenter cycles of natural transformation.

Framing the Inquiry

In her lecture, titled “Art Attacks: Museum Vandalism as a Populist Response to Climate Trauma?” Dr. Hart asked two provocative and interrelated questions: Can climate-motivated attacks on cultural heritage be understood as populist interventions? And are such acts animated by collective trauma in response to escalating ecological collapse?

Drawing on her intellectual background in German studies and arts-based environmental research, Dr. Hart invited participants to think critically about what lies behind these acts of museum vandalism—actions that, at first glance, may seem merely destructive but are laden with symbolism and ambiguity. In doing so, she framed her lecture around key themes that set the tone for further discussion: populism, affect, trauma, artistic disruption, and cultural elitism. Through this framing, she encouraged participants to interrogate how contemporary protest blurs boundaries between art and activism, and how cultural heritage itself becomes a site where competing visions of justice, grief, and ecological survival play out.

Dr. Hart began by situating her own intellectual journey—from early research on music as resistance during the Nazi era, where she explored how art could disrupt authoritarian propaganda’s narcotic appeal, to her current focus on the affective and symbolic power of art in the context of environmental crises. This personal trajectory underscored a continuity in her work: a persistent interrogation of how artistic practices can interrupt complacency, provoke reflection, and mobilize engagement.

In today’s context, she argued, museum vandalism by climate activists invites interpretation beyond its surface-level appearance as mere destruction. While many view these actions as disruptive irritations—summarized in a tongue-in-cheek remark she recalled from a recent Oxford symposium, “Everyone hates climate activists”—Dr. Hart challenged participants to probe more deeply: why and how are these interventions disruptive, and could they be productive in drawing attention to the climate emergency?

She acknowledged that her presentation, though informed by her expertise in sound and music, would focus more on visual art, reflecting the prominence of museum spaces as recent sites of climate protest. The lecture’s key themes—populism, trauma, and the aesthetics of disruption—were introduced as analytical frames through which to interrogate these acts of vandalism. Dr. Hart signaled that she would offer preliminary thoughts while leaving ample space for dialogue, emphasizing that these questions remain open and contested.

By foregrounding her inquiry in this way, Dr. Hart set the stage for a rich exploration of not only whether climate activist vandalism constitutes a populist response but also how it may serve as an expression of collective climate grief and a critique of cultural elitism. This framing invited participants to think critically about the ambiguous and provocative role of art in times of ecological crisis and political polarization.

Museum Vandalism as Performative Protest

In her lecture, Dr. Hart has drew attentions to a striking phenomenon that has emerged in recent years: the vandalism of iconic artworks by climate activist groups. Framing these incidents as potential cases of “performative protest,” Dr. Hart explored not only their aesthetic shock value but their underlying motivations and rhetorical strategies, situating these acts within broader cultural and political debates.

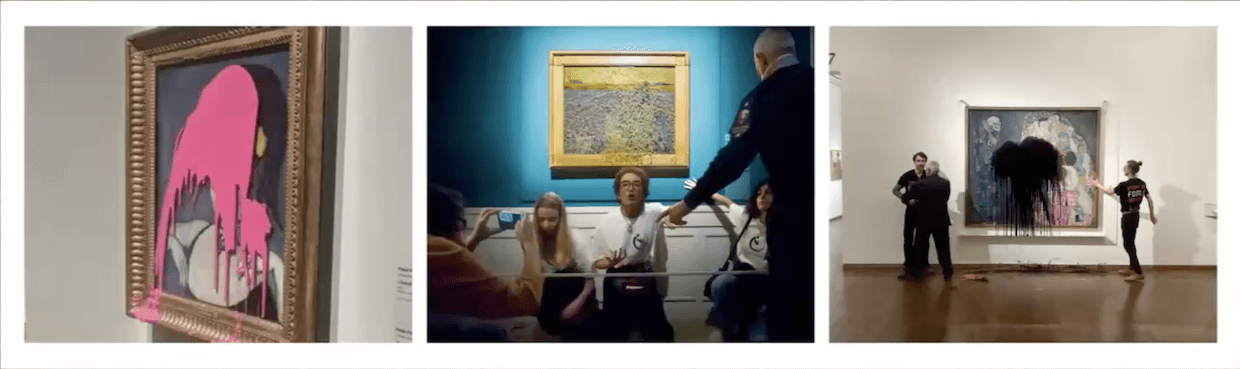

She began by providing concrete examples of such actions. In 2022, museum vandalism became a prominent feature of climate activism, with protesters targeting cultural masterpieces in acts carefully calibrated for visibility. Dr. Hart discussed a recent attack in Montreal, where pink paint was thrown at Picasso’s Le Tête. Other high-profile incidents included activists hurling pea soup at Van Gogh’s The Sower in Rome, and black paint splashed on Gustav Klimt’s Death and Life in Vienna. These actions, though dramatic, typically did not cause irreversible damage. As Dr. Hart noted, most of these targeted paintings were protected by glass or varnish, meaning the interventions were more symbolic than materially destructive.

Yet, the symbolism itself was deeply provocative. The activists’ chosen targets were canonical works—artworks regarded as cultural treasures—imbued with historical and aesthetic value. The protests’ visual violence demanded attention but also raised questions about the meaning of “treasuring” art in an age of ecological collapse. Dr. Hart highlighted the activists’ rhetorical position: Why admire art while the planet burns? For these groups, art becomes a symbol of elitism and privilege, and their interventions serve to challenge that perceived complacency.

Who perpetrates these actions? Dr. Hart shared that the vast majority—about 95%—are carried out by organized groups, typically operating within their own countries and avoiding long-distance air travel for environmental reasons. Three major groups—Ultima Generazione in Italy and the Vatican, Just Stop Oil in the UK, and Letzte Generation in Germany—account for over half of such incidents globally. These groups share coordination mechanisms, including networks like “A22,” and their communications reflect a shared sense of existential urgency. As their manifesto proclaims: “The old world is dying. We are in the last hour. What we do now decides the fate of this world and the next.”

Dr. Hart unpacked the dramatic language used by these groups, noting how their invocation of being the “last generation” implies both despair and futurity. On one hand, their rhetoric signals apocalyptic loss—both ecological and cultural—while on the other it invokes protection of generations yet to come. Their critique extends beyond climate change itself to the cultural frameworks that structure inaction: museums and artworks become proxies for a broader critique of elite indifference to planetary crisis.

The lecture also probed the deeper ideological terrain of these protests, linking them to contemporary struggles over rights discourse. Dr. Hart reflected on how activist groups claim an “inalienable right” to protest through disruptive means—a phrase that resonates with the language of populism on both the left and right. In today’s polarized context, she observed, concepts like “freedom” and “rights” are highly contingent, shifting according to political alignment. Where once calls for “freedom” in the US were often heard from right-wing movements opposing government regulation, the post-2024 political landscape has seen left-leaning groups appropriating the same rhetoric to resist new authoritarian currents.

Thus, these acts of museum vandalism reflect not only artistic disruption but also a contest over language itself—over what rights mean, who can claim them, and in what contexts. Dr. Hart emphasized that the activist invocation of freedom and rights is part of a wider populist dynamic that questions authority and elite cultural spaces, even as it seeks to defend collective planetary futures.

Dr. Hart’s exploration of climate activist vandalism revealed these actions as complex, ambiguous performances: visually disruptive yet materially restrained, symbolically powerful yet ideologically contested. By probing their underlying motivations, rhetorical strategies, and populist dimensions, she invited participants to view these protests not simply as acts of destruction but as calls for attention to deeper crises of climate, culture, and democracy itself.

Populist Dynamics and Iconoclash

In her lecture, Dr. Hart also offered an expansive reflection on the relationship between contemporary climate activism, populist dynamics, and artistic practice, emphasizing how recent acts of vandalism against artworks in museums embody complex cultural and ideological tensions. Dr. Hart examined why some climate activists engage in such performative protests, throwing substances on masterpieces as a way to challenge the cultural hierarchies that museums symbolize.

She framed this as a populist gesture, drawing on arguments in the Encyclopedia of New Populism (2024), which describe left-oriented populist activists viewing museum art as symbolic of elitism. These artworks, attributed with immense monetary and cultural value, are seen to set apart a privileged cultural elite (“them”) from the general public (“us”). For these activists, museums become metaphoric “ivory towers,” and vandalism functions as a provocative performance rather than a reactionary outburst. In this framing, the splashing of paint or soup on a painting is not mere destruction, but a deliberate disruption aimed at exposing what they perceive as misplaced societal priorities in a time of environmental crisis.

Dr. Hart then broadened this inquiry by situating these acts within an evolving discourse in the art world itself. Museums today are increasingly sites of reflection on their own complicity in colonial histories, leading to active debates about “decolonizing the museum.” Many institutions are critically reassessing their collections—particularly artifacts acquired during imperial periods—and grappling with ethical questions of provenance and restitution.

Closely linked to these debates is the burgeoning discourse of posthumanism, another current Dr. Hart identified as central to understanding the contemporary art world. Posthumanism, she explained, takes two key forms: one engages with technological transformation, contemplating the future of humanity in an age of AI and bodily augmentation; the other de-centers humans as the central agents in history and culture, emphasizing human entanglement with non-human animals, ecosystems, and material forces. This second strand, Dr. Hart noted, deeply informs the proliferation of artworks today that abandon traditional materials like oil paint and canvas in favor of organic or ephemeral substances—horsehair, moss, soil, cultivated bacteria—all signaling a shift away from an anthropocentric worldview.

In this context, Dr. Hart suggested that climate activist vandalism tends not to target contemporary works that already embrace this ecological sensitivity. Instead, activists have focused on older, canonical works of art that are emblematic of human exceptionalism and Western aesthetic traditions. Their interventions thus function as a critique of a cultural legacy that they see as complicit in ecological extraction and exploitation.

Returning to the theme of populism, Dr. Hart introduced the work of political theorist Chantal Mouffe, whose book Toward a Green Democratic Revolution: Left Populism and the Power of Affects argues that left populism is a vital mode for mobilizing collective political will in the face of ecological collapse. For Mouffe, affective energy—passion, anger, grief—must be harnessed not just as protest but also channeled into institutional processes like voting and policymaking. Dr. Hart affirmed that Mouffe’s ideas offer a strong theoretical justification for interpreting climate activist actions as populist interventions aimed at reconfiguring democratic priorities around ecological survival.

However, Dr. Hart was careful to draw an important distinction between left populist climate activism and right-wing eco-fascism. Though both can appear populist in form, their ideological contents diverge dramatically. Eco-fascism, she observed, is often animated by a Malthusian impulse to restrict human populations, frequently tied to racialized or exclusionary worldviews—a “protection of the earth” that serves a narrowly defined community, often coded as white. In contrast, left populist climate activism typically expresses solidarity with all humans and non-humans alike, animated by a vision of ecological justice that centers collective responsibility and inclusivity.

An instructive example here is the “seven-generation principle,” drawn from Indigenous philosophies, which advises that every decision be made with consideration for its impact on seven generations to come. Dr. Hart explained that this principle encapsulates a form of temporality and collectivity that stands in stark opposition to the extractive logic of neoliberal capitalism. Where eco-fascists would advocate reducing populations to “protect” the earth, left populists call for an expanded, solidaristic ecology that embraces future human and non-human lives alike.

Dr. Hart then turned to the language of passion and affect in this context. While critics often dismiss passion as unstructured and chaotic, Mouffe and others argue that passion is essential for building a political project powerful enough to challenge entrenched structures of extraction and domination. Activism in museums, from this perspective, should not be seen as mindless vandalism but as part of a broader affective politics—a politics that seeks to reorient collective attention from cultural elitism to planetary emergency.

Dr. Hart continued her lecture by introducing the provocative concept of iconoclash, coined by French philosopher Bruno Latour. Distinct from “iconoclasm,” which implies a clear intent to destroy sacred images, iconoclash suggests a productive ambiguity: an act that simultaneously destroys and provokes reflection. When activists splash paint on canonical artworks, they may not seek to obliterate their cultural value outright but to force a public reconsideration of what those values signify at this moment of ecological precarity.

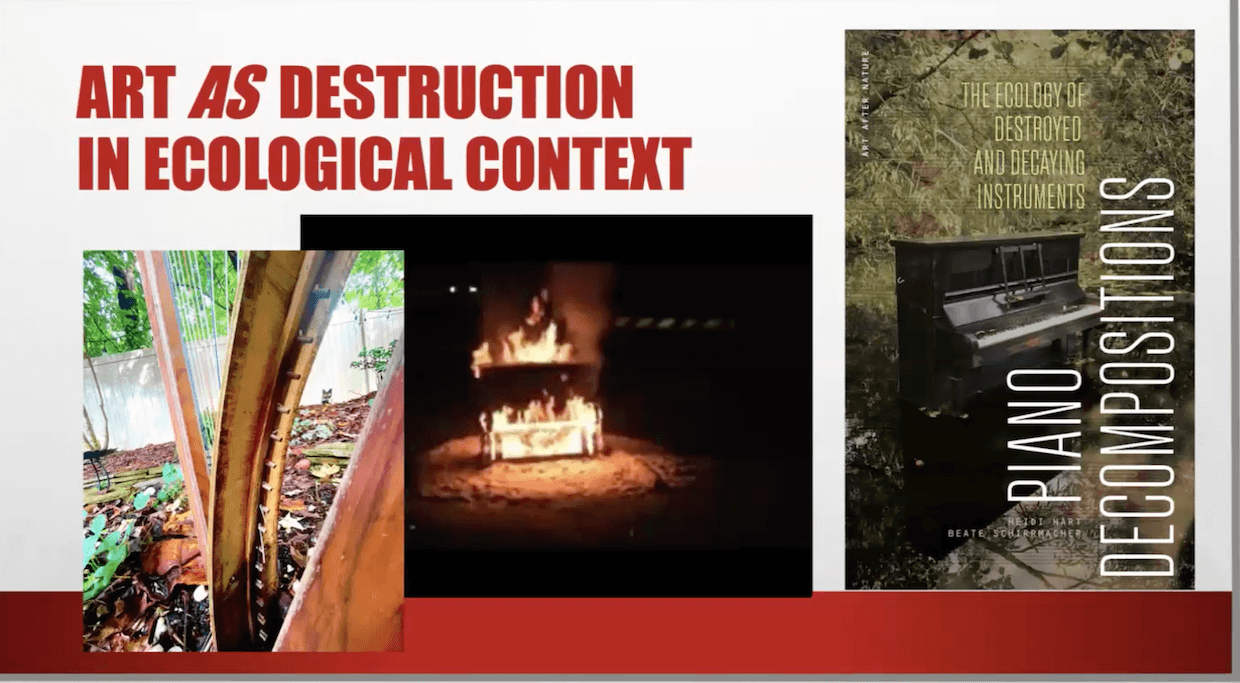

This framing resonates with Dr. Hart’s own scholarly and artistic work. She shared insights from her forthcoming book Piano Decompositions: The Ecology of Destroyed and Decaying Instruments, co-authored with Beata Schirrmacher, which explores how broken or abandoned instruments—burning pianos, rotting harps—become ecological sites in their own right. A decaying harp in her own backyard, she explained, has become home to spiders and plants, its strings transformed into webs, its wooden frame absorbing rain and wind. Such work re-embeds cultural artifacts into natural cycles of decay and regeneration, proposing destruction itself as a mode of ecological engagement.

In this light, Dr. Hart suggested, climate activist attacks on canonical artworks might also be understood not simply as negations but as attempts to transform how society values cultural and material artifacts—raising questions about what should be preserved, what should be mourned, and what should be allowed to return to the earth.

Trauma, Affect, and Eco-Populism

Moreover, Dr. Hart addressed the psychological and emotional dimensions underlying acts of climate activism that target cultural institutions, focusing on the role of trauma and affect. She posed a central question: Are these destructive actions simply about drawing attention to the climate crisis, or do they emerge from an emotional intensity—what Chantal Mouffe describes as a passion driven by collective hurt and grief over ecological loss?

Dr. Hart cited Catherine Stiles’s work on destruction art as a useful lens, noting that such artistic interventions can be seen as a visual expression of the trauma of survival itself. According to Stiles, destruction art embodies the precarious condition of human survival in the 20th and 21st centuries, echoing broader existential anxieties that are increasingly acute amid escalating climate disruptions.

Dr. Hart also referenced Ian Kaplan’s Climate Trauma, a study exploring dystopian narratives across film and fiction, as further evidence of how popular culture processes this collective sense of impending ecological catastrophe. She observed that dystopian imaginaries reflect an implicit recognition that the world as we know it has already ended—a powerful backdrop for understanding the emotional logic of activist vandalism.

Drawing connections to current events, Dr. Hart emphasized that even those not directly affected by disasters like recent floods in Texas experience a form of mediated trauma through relentless news coverage. This ambient, cumulative distress, particularly among younger generations contemplating their futures, helps explain why destructive activism may increasingly be motivated not only by strategic intent but also by genuine emotional exhaustion and eco-anxiety.

In concluding her lecture, Dr. Heidi Hart offered a compelling reflection on the potential of artistic ambiguity and creative narratives to engage with ecological crisis in ways that transcend binary thinking. She highlighted the Icelandic film Woman at War (2013) as an exemplar of this approach, noting how its protagonist—a passionate eco-warrior—embodies a complex duality: she actively sabotages industrial infrastructure in Iceland while also serving as a beloved choir director in Reykjavík, deeply invested in her community and the arts.

Dr. Hart described how the film explores the interplay between destruction and creativity, emphasizing the ambiguity at its core. Throughout the film, a roving ensemble of musicians appears in unexpected settings—on hillsides, in the protagonist’s apartment, at an airport runway—blurring the lines between reality and imagination, and inviting viewers to question the role of art and music during times of crisis. This device creates a distancing effect that allows for reflection on art’s relevance when ecological and social structures are under threat. She also pointed out how the film weaves in another narrative thread: the protagonist’s pending adoption of a child from Ukraine, adding further layers of ethical complexity around responsibility, personal obligations, and global injustice.

Dr. Hart praised the film’s ability to offer hope without sacrificing complexity or humor. She encouraged participants to consider creative, less binary ways of thinking about activism, destruction, and repair, and left them with key questions: Can we understand these acts as a form of left-wing populism? Are they rooted in trauma? And can artful destruction productively draw attention to planetary crisis?

Conclusion

Dr. Heidi Hart’s lecture for the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025 offered participants a rich and provocative framework for understanding contemporary climate activism’s engagement with art, populism, and trauma. By tracing the phenomenon of museum vandalism through multiple analytical lenses—political, cultural, and affective—she challenged easy dismissals of such acts as mere nihilism or spectacle. Instead, she invited participants to interpret these performative protests as complex interventions that reflect an urgent critique of cultural elitism, a contest over the meaning of “rights” and “freedom,” and a passionate response to collective eco-anxiety.

Throughout her talk, Dr. Hart emphasized the importance of nuance and ambiguity. She invoked Bruno Latour’s concept of “iconoclash” to describe how these interventions simultaneously destroy and provoke reflection, suggesting that climate activist vandalism compels society to reconsider what it treasures, preserves, or lets decay. Drawing on her own research on the ecology of destroyed instruments, she extended this theme to propose that destruction itself can become a creative act—reembedding human culture within natural cycles of decay and renewal.

In concluding, Dr. Hart highlighted the Icelandic film Woman at War as a hopeful model for thinking beyond binaries of destruction versus creativity, or human versus nature. She encouraged participants to explore how affective politics, populist passion, and artistic ambiguity might offer new modes of engaging with ecological crisis.