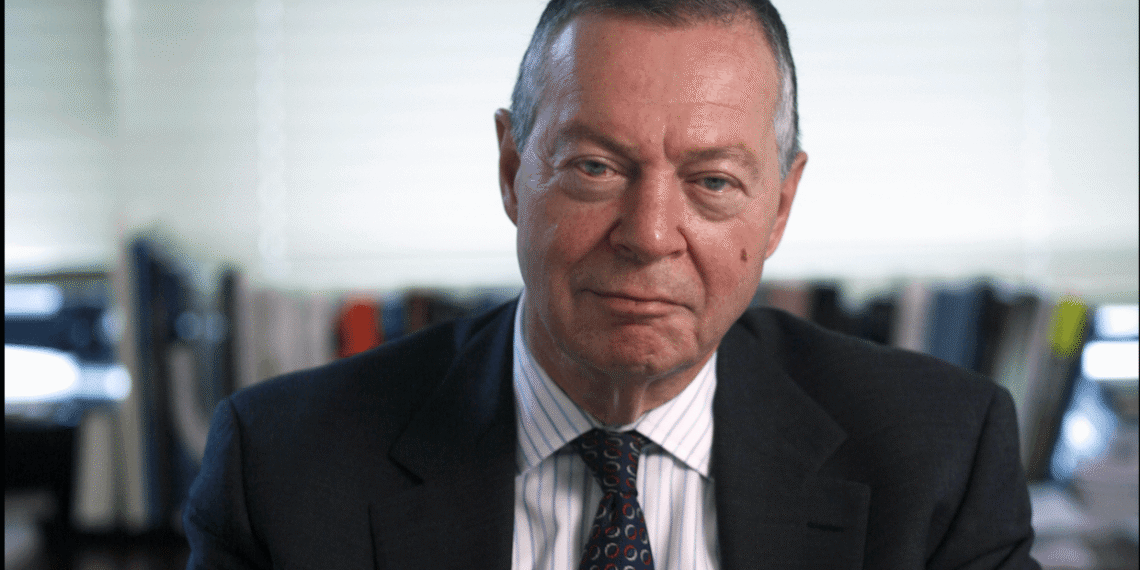

In an exclusive interview with the ECPS, Aryeh Neier — founding Executive Director of Human Rights Watch and former President of the Open Society Foundations — delivers a powerful assessment of Gaza, free speech, and international accountability. Neier argues that criticism of Israeli policies must not be conflated with antisemitism, stressing that “even antisemitism constitutes protected speech.” He further asserts that “Israel is engaged in genocide,” citing systematic obstruction of humanitarian aid and disproportionate force in Gaza. While the ICC remains “the only viable path” for justice, he warns that political barriers persist. From US policy dynamics to global human rights challenges, Neier offers rare insights into one of today’s most divisive debates.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

Giving an interview to the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), iconic human rights defender Aryeh Neier — former Executive Director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), founding Executive Director of Human Rights Watch (HRW), and former President of the Open Society Foundations — reflects on Israel’s war in Gaza, free speech controversies, and the challenges of international accountability. With a career spanning more than six decades and seven honorary degrees, Neier brings unmatched authority to one of today’s most polarizing debates.

At the heart of the conversation lies his assertion that criticism of Israeli policies must not be conflated with antisemitism. “Differentiating antisemitism from anti-Israel speech is something that the Trump administration has failed to do,” Neier argues, highlighting how US political discourse has blurred the lines between prejudice and legitimate dissent. He warns against undermining free expression on American campuses: “Even antisemitism constitutes protected speech,” he insists, while adding that universities must balance academic freedoms with preventing disruption to institutional activities.

Turning to Gaza, Neier presents a grave legal assessment: “Israel is engaged in genocide,” he says, grounding his conclusion in the 1948 Genocide Convention. He points to two central factors: Israel’s sustained obstruction of humanitarian aid and the use of disproportionate force. “Starvation, as a method of warfare, is forbidden under the First Protocol of the Geneva Conventions,” he stresses, adding that the denial of food, water, and medical supplies, combined with the use of 900-kilogram bombs in densely populated areas, “seems to me to amount to the crime of genocide.”

Aryeh Neier also emphasizes the limitations of international mechanisms. While the International Criminal Court (ICC) remains the most viable forum for prosecutions, enforcement will require political shifts. Drawing parallels to the former Yugoslavia, he notes, “Slobodan Milosevic never imagined he would face trial, yet years later he was sent to The Hague.”

On US policy, Neier identifies Evangelical Christian groups, not AIPAC, as a dominant influence shaping Washington’s stance toward Israel, complicating responses to international legal rulings. He also warns of growing generational divides within US politics, with younger voters increasingly critical of Israeli policies — a factor he believes may eventually reshape policy debates.

This interview offers a profound exploration of the intersection between human rights, international law, free speech, and accountability. From Gaza to US campuses, Neier challenges political distortions and underscores the urgency of protecting both humanitarian principles and civil liberties in an age of polarization.

Here is the transcript of our interview with human rights champion Aryeh Neier, lightly edited for clarity and readability.

Why Gaza Meets the Genocide Threshold

Mr. Aryeh Neier, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: As one of the most influential human rights defenders in modern history, you have stated that you are persuaded Israel is “engaged in genocide” in Gaza. How do you define genocide in this context under international law, and how do Netanyahu’s increasingly populist and authoritarian coalition policies — particularly regarding humanitarian aid, military conduct, and civilian protections — factor into your conclusion that the legal threshold has been crossed?

Aryeh Neier: As far as the legal definition of genocide is concerned, it is the 1948 Genocide Convention that defines the crime under international law. The crime consists of destroying a national, racial, ethnic, or religious group, in whole or in part. This destruction can occur through direct killing or by creating conditions of life intended to bring about the death of such a group, in whole or in part. The attempt to commit genocide is also a crime under international law, just as the actual commission of genocide is. Regarding those who organize the effort, I’m less focused on the coalitions they may form. To me, the guilty parties are those who possess both the authority and the intent — and intent is the crucial factor under international law in defining the crime of genocide.

You have linked your conclusion primarily to Israel’s sustained obstruction of humanitarian aid. From a legal perspective, do you interpret starvation as a method of warfare here as evidence of specific genocidal intent to destroy a population, in whole or in part? To what extent does Netanyahu’s populist-nationalist rhetoric and reliance on far-right coalition partners signal deliberate policy intent rather than reckless disregard?

Aryeh Neier: Again, I’m not concerned with the coalition that may be supporting Netanyahu. The issue is whether they exercise the authority that makes them guilty participants in the crime of genocide. Starvation, as a method of warfare, is forbidden under the First Protocol of the Geneva Conventions. It is absolutely prohibited, and those who act with intent to cause starvation should be considered to have participated in the commission of genocide.

Although I focus heavily on the denial of humanitarian assistance — including food, water, and medical supplies — to the population of Gaza, I would also include, as part of the crime of genocide, the use of disproportionate force by the Israeli government. For example, the Israeli government used 900-kilogram bombs in its attacks on Gaza, particularly in the early months. Bombs of that size can kill people within 200 meters and are utterly inappropriate for use in a densely populated area like Gaza.

While such weapons might have legitimate uses in warfare — for example, destroying a naval base or a military factory producing large amounts of armor — their use in crowded urban areas inevitably means that a very large number of civilians will be killed, and that is what happened in Gaza. Therefore, the combination of the way these attacks were carried out and the denial of humanitarian assistance, including food, water, and medical supplies, seems to me to amount to the crime of genocide.

From Blockades to Bombing Patterns

Based on your experience at Human Rights Watch and the Open Society Foundations, which forms of evidence are most critical for establishing war crimes liability in Gaza — convoy interdictions, caloric deprivation, bombing patterns, or policy directives?

Aryeh Neier: All of the above are factors that can be considered as evidence. If there were to be a criminal trial in the International Criminal Court (ICC), there would need to be clear evidence showing what the defendants actually did. There would have to be witnesses who could testify to their actions, as well as an examination of any available documents, along with testimony from observers who were present. The Israeli government has done as much as it could to limit the possibility of such testimony by preventing international journalists and human rights groups from entering Gaza. Therefore, the witnesses would most likely have to be people from Gaza who experienced these crimes, along with some Israelis who are knowledgeable about the practices and could testify before the ICC.

Given the populist pressures within Netanyahu’s coalition, which levels of command responsibility appear most salient — cabinet-level policy decisions, directives from the defense establishment, or field-level operational orders? How should investigators document the causal link between strategic blockade policies, child malnutrition, and elevated civilian mortality?

Aryeh Neier: I don’t think one can specify in advance how a prosecution would proceed. It would be up to the prosecutors to determine what evidence they are able to obtain. If they can secure military directives, they would use those. But if they are not able to access such directives, testimony from individuals who were present when decisions were made would become important. If that is also unavailable, they would need to examine patterns of action by those who committed the crimes. They would look at actions taken, for example, to destroy farms and greenhouses in Gaza, which provided some of the food. They would examine those who obstructed trucks attempting to deliver assistance and review the orders that limited the number of trucks entering Gaza. All of these would be factors. It’s impossible to specify in advance what evidence the prosecutors would rely upon.

ICC Remains the Only Path for Gaza War Crimes Accountability

You once critiqued the UN Human Rights Council’s bloc politics and selective scrutiny. How should advocates leverage UN mechanisms on Gaza while mitigating the reputational drag of perceived selectivity and ensuring even-handed standards?

Aryeh Neier: The UN Human Rights Council is a political body. The various governments that serve on the Council at any given moment have their own political interests. They often form blocs, and, to some extent, those blocs protect the countries that are members of them. So, if one is dealing, for example, with crimes committed in Sudan, there may be African countries that have alliances with Sudan or obtain oil from it, and those countries may be protective of the Sudanese government. Similarly, when addressing Russia’s crimes in Ukraine, there may be countries from the former Soviet Union that still maintain alliances with Russia and would shield it from scrutiny. It is, therefore, impossible to rely on the UN Human Rights Council as a fully neutral body capable of making impartial decisions on crucial human rights matters. One tries, as much as possible, to mitigate that factor, but it cannot be entirely eliminated.

Having been a key advocate for the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Rwanda (ICTR), how do you compare the feasibility of creating a similar ad hoc tribunal for Gaza versus relying on the International Criminal Court (ICC)? What lessons from Bosnia and Rwanda are relevant here, and which pitfalls should be avoided?

Aryeh Neier: The reason it was possible to create the tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda is that the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council all accepted the establishment of those bodies. None of them exercised their veto power to block their creation. Unfortunately, if there were an attempt to create an ad hoc tribunal along the lines of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia or the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the United States would almost certainly exercise its veto to prevent the formation of such a body. Therefore, I don’t think we can expect that there will ever be a special tribunal for Gaza. I believe the International Criminal Court, which is not subject to such veto power, remains the only possibility for criminal prosecution for the crimes committed in Gaza.

European Courts May Pursue Cases Against Israeli Officials

If Israel were to initiate domestic investigations into alleged violations, how should the ICC evaluate their credibility under complementarity rules? In the absence of genuine proceedings, should European states more aggressively invoke universal jurisdiction to pursue accountability?

Aryeh Neier: One could evaluate whether Israel is acting in good faith in prosecutions in the same way one evaluates any other situation in which there could be prosecutions. That is, is there a genuine investigative process, and does the investigative process actually lead to indictments? If Israel were to claim that it is engaged in an investigation and its performance does not inspire credibility, then I think the International Criminal Court should proceed on the basis that Israel is not doing what it should, and therefore only the International Criminal Court is capable of bringing such a prosecution.

I think it’s entirely possible that some European countries will, at some point, exercise universal jurisdiction with respect to crimes committed in Gaza. It is likely that Israelis will travel to various European countries. The countries that have condemned the crimes taking place in Gaza may become aware that someone who was a military figure is traveling within their borders, and in those circumstances, one could imagine that universal jurisdiction would take place.

There have been, for example, a number of prosecutions in European countries of Syrian officials who traveled in different European countries — in Switzerland, for example — and Switzerland used universal jurisdiction to bring such persons to trial. I don’t imagine this would involve the highest-level Israeli officials, the people who have the most significant responsibility for the crimes committed in Gaza. But I think it could well happen that there will be such cases, and we won’t know until it actually happens whether there will be such trials.

There are a couple of organizations. There’s an organization based in Switzerland, for example, called Trial, which specifically looks for such cases and tries to ensure prosecutions take place. I don’t know whether they’re looking at any cases right now; they might be, they might not be. I think most of the Israeli officials who have a high level of responsibility for the crimes in Gaza are avoiding travel to European countries.

Future Political Shifts Could Open Door to Prosecutions

You have noted that both the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the ICC lack direct enforcement powers and rely on state cooperation. What realistic regional or transnational coalitions, in your view, could translate court rulings into tangible protection or material relief for civilians in Gaza?

Aryeh Neier: I’m not sure that an international coalition could achieve that. I think the critical step is to try to bring a case before the International Criminal Court. The ICC has jurisdiction over individuals, not countries. And if, at some stage, it was possible to bring top officials responsible for the crimes in Gaza before the ICC, that would be the way to secure some form of accountability.

When the wars in the former Yugoslavia took place, the officials responsible for major crimes never imagined they would face the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Yet, eventually, Slobodan Milosevic was sent to the court by other officials in Serbia, and Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic were ultimately captured and brought before the tribunal.

It took many years. It may also take many years in the case of Gaza. But it cannot be ruled out. It is possible that, over time, there could be political change in Israel and that future leaders might seek to ensure some form of accountability. One cannot predict how this will develop.

According to numerous expert assessments, the US administration may be violating both domestic and international law by supplying arms to Israel despite documented restrictions on humanitarian aid to Gaza. Based on your experience with US accountability mechanisms, do you believe American officials could face future legal challenges under the Arms Export Control Act or under aiding-and-abetting doctrines in international law?

Aryeh Neier: I think I would give the same answer to the question of whether Israeli officials might, at some stage, face accountability and eventually be held responsible. One cannot predict how matters will develop politically in the United States. It is unlikely that the Trump administration would pursue the prosecution of those who may be complicit in the genocide taking place in Gaza. However, one cannot know who the officials will be in the United States 10, 15, or 20 years from now, and it is possible that, at some stage in the future, there might be a willingness to prosecute American officials. I would not say it is likely, but it’s possible.

Evangelical Influence Shapes US Policy Toward Israel

You have emphasized that Evangelical Christian groups, rather than AIPAC, exert disproportionate influence on US policy toward Israel. How does this ideological alignment affect Washington’s responses to ICJ and ICC proceedings?

Aryeh Neier: Certain evangelical groups in the United States have managed to incorporate Israel and its prospects into their theology. These groups are particularly strong in the southern states, creating a powerful political bloc that is immensely supportive of Israel. A prominent figure within that bloc is Mike Huckabee, a former governor of Arkansas, whom the Trump administration has designated as its ambassador to Israel. Placing someone like that in such a key diplomatic position highlights both the strength of this bloc within the United States and the political difficulty of overcoming its influence.

You had warned that President Biden risks losing young voters over his handling of Gaza. To what extent do you see US domestic politics colliding with international humanitarian law — and could electoral considerations meaningfully shift US policy?

Aryeh Neier: There has been a generational division in the United States. Among other things, older members of the Jewish community have tended to be very supportive of Israel, whereas many younger Jews, particularly those attending universities, are often highly critical of the Israeli government’s policies. I believe this divide extends beyond the Jewish population to the broader American public. The generational gap is quite wide, but how it will ultimately play out is uncertain. It may become a significant factor in shaping US policy in the years to come, or it may not.

Refusing to Buy Israeli Weapons May Pressure Policy Change

In your work on sanctions and human rights, you have argued that targeted measures can drive behavioral change. In Gaza, which tools — such as asset freezes, travel bans, or conditionality on arms transfers — would be most effective in influencing policy without exacerbating civilian suffering? Looking at past cases such as Myanmar and South Africa, sanctions’ effectiveness often depends on timing and international coordination. What benchmarks should be used to assess whether external pressure is genuinely shaping Israel’s policy on humanitarian access?

Aryeh Neier: It’s very difficult to answer that question. I would not have imagined, before the sanctions were placed on South Africa, what would be most effective. But I think that, in the case of South Africa, for example, the international sports ban had a significant effect. South Africans, like the people of many countries, were very supportive of their athletes and eager to see them succeed in international competitions. When South African athletes were excluded from such events, it had a considerable impact. Economic sanctions also had a significant effect.

My guess is that, in the Israeli situation, the most significant kinds of sanctions would be those that impose limits on military support for Israel. Israel is itself a significant manufacturer of arms, and much of its international revenue comes from arms sales to various countries. So, I think that if sanctions were imposed, there should be two kinds: one, a sanction on the delivery of weapons to Israel, and the other, a sanction on the purchase of Israeli weapons.

I once spoke to an Israeli official about limiting the sale of certain weapons to other countries that were engaged at that time in very serious human rights abuses. He explained that, for Israel’s arms manufacturing to produce the weapons Israel believes it needs, the country must achieve economies of scale by manufacturing far more weapons than it actually requires for its own purposes. Therefore, it has to sell those weapons to other countries. Selling weapons internationally, he said, was crucial for Israel’s own military needs.

My guess is that this is probably still the case. Therefore, if sanctions involved refusing to purchase Israeli weapons, that might be as effective as refusing to sell certain weapons to Israel.

Anti-Israel Speech Shouldn’t Be Confused with Antisemitism

As someone who defended free speech in the Skokie case, how do you distinguish between antisemitism and legitimate criticism of Israeli state policies — especially in today’s polarized academic, civic, and political environments?

Aryeh Neier: Differentiating antisemitism from anti-Israel speech is something that the Trump administration has failed to do. It has attacked many universities in the United States, accusing them of allowing antisemitism to flourish on their campuses. Very often, however, the protests that have taken place on American campuses are directed against Israeli practices rather than being antisemitic in character. From a free speech standpoint, my view is that even antisemitism constitutes protected speech.

It isn’t the case, however, that many universities in the United States are public institutions where the First Amendment’s free speech guarantees apply. Many of the universities accused of allowing antisemitism on their campuses are private universities, like Harvard University and Columbia University, and they are not required to adhere to First Amendment protections. Nevertheless, in general, they do try to protect freedom of speech.

I believe they can and should protect freedom of speech, even for antisemites, but they should not allow such individuals to disrupt university activities, such as classes, graduations, or other events. So, one needs to look at each of those situations and see whether the university has acted appropriately. But the Trump administration, by confusing antisemitism and anti-Israel positions, has made the whole situation a mess.

Truth Commissions Won’t Deliver Justice in Gaza

And lastly, looking ahead, what model of transitional justice would best address violations committed by all parties — a hybrid court, ICC-led prosecutions, or a regional truth and reconciliation commission with prosecutorial powers? How can victim-centered justice remain central in the face of deep political deadlock?

Aryeh Neier: I think the only possibility of accountability is prosecutions before the International Criminal Court. I don’t imagine that there would be a Truth and Reconciliation Commission that could function effectively because it would have to involve both the Israelis and the Palestinians, and it’s very difficult to imagine that they would collaborate on a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Moreover, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission would not itself have prosecutorial powers. In the case of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, there was legislation which provided that those who did not disclose their crimes and acknowledge their crimes still could be prosecuted. But the prosecution was separate from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission itself, and in practice, not that many persons who had committed crimes during the apartheid regime were actually prosecuted in South Africa, even when they refused to acknowledge and disclose the crimes that they committed.

So, I’m not at all inclined to think that a Truth and Reconciliation Commission could play a useful role in the situation of Gaza. I think, as difficult as it may be, one should try to see to it that the International Criminal Court is able to function with respect to the crimes committed in Gaza.