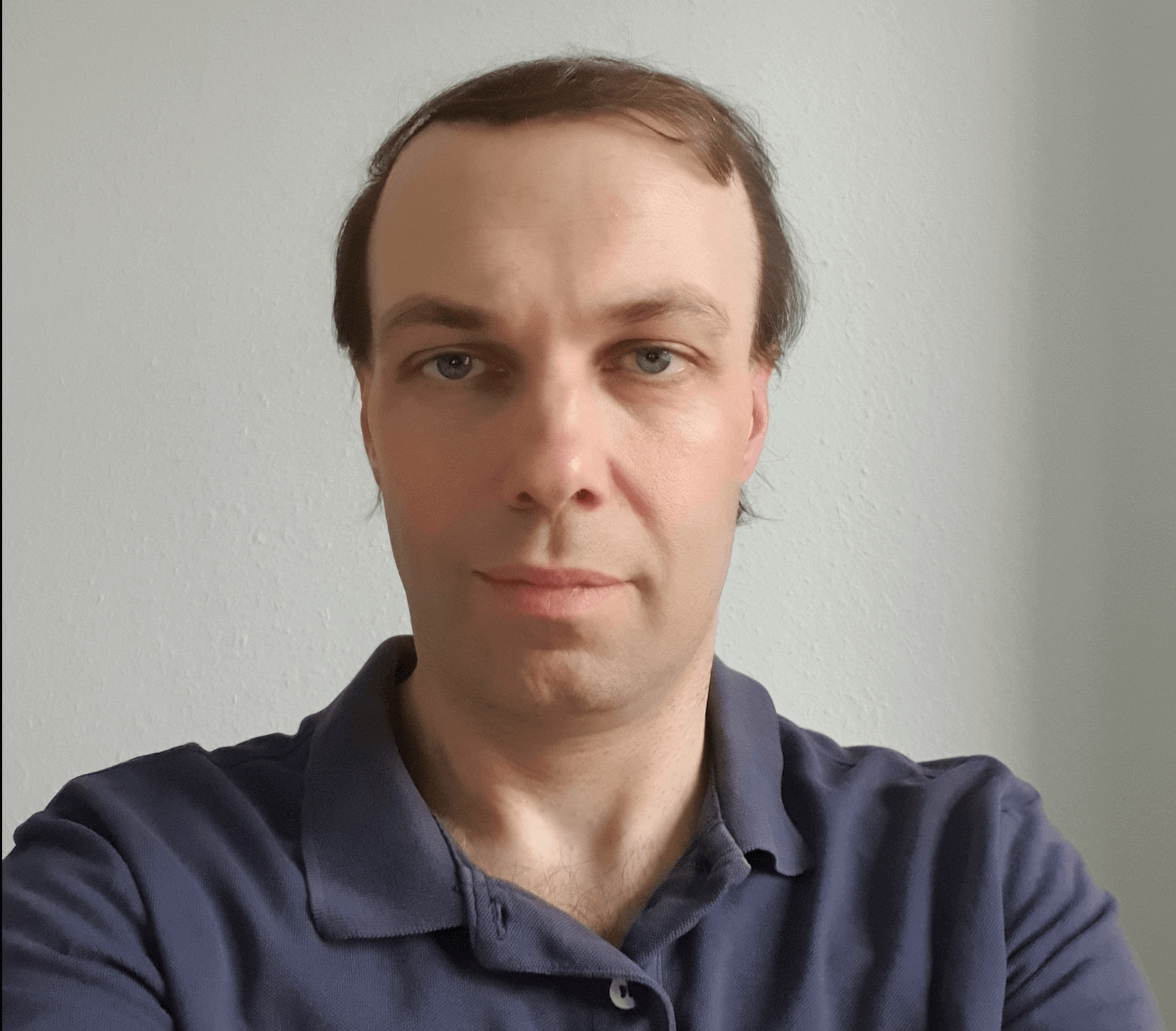

Professor David Aprasidze: In Georgia, the Georgian Dream party exemplifies a technocratic form of populism, treating state governance like corporate management. Founder Bidzina Ivanishvili, a former businessman, brings a non-ideological, efficiency-focused approach, applying principles from his business career to politics. He appoints key officials as “managers” to carry out strategic directives, allowing him to remain distanced while exercising control. This model emphasizes expertise and governance over ideology, with Ivanishvili viewing the state as if it were one of his companies.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In a revealing interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. David Aprasidze, political science professor at Ilia State University in Tbilisi, sheds light on how Bidzina Ivanishvili, the founder of Georgian Dream, has transformed Georgian governance through a “technocratic populism” model. According to Professor Aprasidze, Ivanishvili “treats the state almost as if it were a business,” blending his extensive business experience with politics to establish a unique governance style that sets Georgian Dream apart from other political movements. Ivanishvili, who made his fortune in Russia in the 1990s, sees himself as a “highly successful businessman” who can replicate that success in governing Georgia.

Professor Aprasidze further highlights how this approach has affected democratic institutions in Georgia, where the judiciary and parliament operate less as independent bodies and more as extensions of Ivanishvili’s centralized authority. This concentration of power, Aprasidze suggests, marks a significant step back for democracy in Georgia and reveals broader trends of democratic backsliding that align with the recent autocratic shift in Georgian Dream’s populist narrative.

Interestingly, Professor Aprasidze points to Georgian Dream’s evolving relationship with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz Party. Initially, Georgian Dream was aligned with the European Socialists, positioning itself on the center-left, but “especially after the war in Ukraine,” Professor Aprasidze notes, the party quickly pivoted to the far right, embracing nationalist and traditionalist rhetoric. Professor Aprasidze observes that Orbán has become a “close ally and influential mentor to Georgian Dream,” offering a populist playbook that guides their current approach.

Reflecting on the EU’s recent stance, Professor Aprasidze underscores the European Commission’s demands for reform before recommending membership talks with Georgia. Yet he remains skeptical, stating that he and “many observers of Georgia” believe it’s unlikely the current administration will undertake the necessary democratic reforms. With a mixture of caution and insight, Professor Aprasidze’s analysis provides a critical lens on Georgia’s political transformation and its implications for both democratic integrity and EU integration.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor David Aprasidze with some edits.

Georgian Case Illustrates How Populism Can Evolve

David, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question. How and under what circumstances does technocratic populism emerge in hybrid regimes? What are its principal characteristics, and what strategies do technocratic populists use to stay in power and govern? What is its difference from conventional populist parties?

Professor David Aprasidze: The Georgian case illustrates how populism can evolve—its color, content, and format can all shift. I believe we could indeed call the initial period of the Georgian Dream a form of technocratic populism. Now, returning to your questions: What are the main features of this type of populism?

A key feature is that those in power, or those aiming to assume power, possess a specific skill or expertise that sets them apart from others. They are, in effect, free from any rigid ideological stance and do not claim to adhere to one. Instead, they emphasize their ability to govern effectively and improve the lives of ordinary citizens. In Georgia, and particularly with the Georgian Dream, this technocratic approach to populism is reflected in their comparison of state governance to corporate governance, treating the state almost as if it were a business model. One of the most influential people in Georgia today, and the founding father of the Georgian Dream, exemplifies this approach. He comes from a business background, having built his fortune in Russia in the 1990s, and sees himself as a highly successful businessman. By bringing his business experience into politics, he positioned himself as someone who could replicate his business success in governing the country. He claimed that the principles he used to run a business would similarly apply to running the country, treating it as if it were one of his companies.

If we combine these features, first, they possess technical expertise. Second, they do not have or embody a strong ideological basis. Third, they bring business experience and apply similar principles to politics. This forms the foundation.

In Georgia, this approach was implemented by Bidzina Ivanishvili, who selected his followers—party members and especially those in government—as he would select managers in his own company. Acting as a stakeholder, he owns the “business” but hires managers to run it on his behalf. He is not involved in every routine decision; instead, his operatives carry out his strategic directives. Thus, the Prime Minister, Ministers, Speaker of the Parliament, and Chairman of the party function as his managers, each responsible for a specific area he has entrusted to them. Naturally, he can replace them based on their performance. If he’s dissatisfied, he can easily remove them and appoint new managers. This, in essence, was how Georgia was governed until 2022.

Technocratic Populism Poses a Serious Threat to Democratic Principles

How has the technocratic populism influenced the balance of power and the role of democratic institutions like the parliament and judiciary in Georgia?

Professor David Aprasidze: That’s a very good question, as technocratic populism has effectively subjugated these institutions. If we accept that this model describes how Georgia was governed, then all authorities—all institutions—become part of a unified mechanism. In this framework, the judiciary functions somewhat like the legal department of a business, while the parliament serves as a procedural body where policies are developed and drafted. Ultimately, however, these institutions do not balance or oversee one another, as the parliament is supposed to do with the executive. Instead, they operate as interconnected components of a single system—as administrative divisions within what resembles a corporate structure.

This approach is, of course, very harmful to democracy because it undermines key institutions. As you mentioned, both the judiciary and parliament are affected: the parliament loses its authority and prerogative to oversee and check the government, or the executive. The judiciary, similarly, becomes merely a registry, simply implementing decisions handed down from the top rather than making independent judgments. Like other forms of populism, this model is detrimental to democracy—though it employs a different method and approach. Ultimately, it poses a serious threat to democratic principles.

What role does the Georgian Dream’s strategy of managing political opposition through loyalty-based appointments and selective prosecution play in shaping an increasingly autocratic governance model in Georgia?

Professor David Aprasidze: Observing how the Georgian Dream developed over time, starting with their rise to power in 2012, we see that it was a weak coalition. Unlike traditional coalitions in European countries or elsewhere, the Georgian Dream wasn’t a coalition in the conventional sense. Instead, it was a unified front that included various opposition parties on a single list, aiming to challenge the previous government. In 2012, rather than competing individually in elections and forming alliances based on outcomes, these opposition parties came together before the elections. This unity created a diverse front in the initial period, with different politicians in Ivanishvili’s government and Parliament, providing a facade of democracy and contestation.

Starting with the second term in 2016, the Georgian Dream began to remove former allies. Some were co-opted, while others were pushed toward the opposition and marginalized. From 2016 through 2020, during this second period of Georgian Dream’s rule, they gradually co-opted or marginalized various politicians. In this process, they used all necessary means to compromise these individuals—whether through the judiciary, the media, or by corrupting them to the extent that they lost legitimacy to function as an opposition or challenge the ruling party.

They employed a range of methods, including controlled media and propaganda against these politicians, as well as selectively applied judicial actions. Those who remained loyal or stayed silent faced no legal challenges, while individuals who dared to criticize or act as opposition saw law enforcement agencies and the judiciary weaponized against them. Through these threats and by shaping public opinion, the Georgian Dream approached the opposition in a calculated manner, gradually silencing a significant portion of it. By the 2020 elections, the opposition was fractured, divided, and in many cases, effectively silenced.

Georgian Population Remains Strongly Pro-European

To what extent do pro-Russian influences within the Georgian Dream party align with or diverge from the public’s pro-European aspirations, and how might this tension impact Georgia’s trajectory toward EU integration?

Professor David Aprasidze: This is a very good question. We could also reframe it slightly and ask, “Is Georgian Dream pro-Russian or not?” But there is no simple answer. I would say that, as with many populist parties across Europe, there is indeed a certain ideological alignment or shared understanding between Russia and this type of populist party, as they promote similar ideas. They both tend to undermine liberal democracy and the Western-style democracy we associate with Western Europe and other parts of the world. In that sense, they may appear to be natural allies.

However, this isn’t always the case. I wouldn’t argue that Georgian Dream is explicitly pro-Russian; rather, it is primarily pro-Georgian Dream. They seize every opportunity to strengthen their hold on power. Until 2020, 2022, or even the onset of the war in Ukraine, Georgian Dream attempted to maintain a pro-Western facade while operating autocratically behind the scenes. As a result, there was no clear stance. Many voices criticized Georgian Dream, claiming the party’s policies or rhetoric were pro-Russian, but it was challenging to make a definitive judgment on this.

Following the war in Ukraine and Georgia’s attainment of EU candidate status with a formal path to membership, Georgian Dream realized that this status would bring pressure to implement deep and far-reaching reforms—reforms they were unwilling to pursue. As a result, they gradually distanced themselves from the EU’s requirements. Step by step, they began shifting toward an anti-Western, anti-European stance, effectively distancing themselves from the Western sphere. Simultaneously, they increasingly adopted rhetoric similar to that currently used by Russia. Since 2020, and especially after the 2024 elections, this alignment of Georgian Dream with Russian policies has become more visible and noticeable than ever before.

As for the Georgian population, it remains strongly pro-European, as confirmed by public opinion polls and surveys. However, the recent election had contested outcomes, both domestically and internationally. I personally believe it was rigged, with Georgian Dream employing various methods to falsify the results. Still, it is now challenging to gauge the true public opinion.

We may learn more in the weeks and months ahead, depending on whether public protests emerge. If many people take to the streets to oppose Georgian Dream’s autocratization efforts, it would confirm that the Georgian population remains Western-leaning, while Georgian Dream acts in opposition to this will, effectively “capturing” the state. However, if there isn’t significant public protest or resistance, we may need to reassess our understanding of public opinion on this issue. Hopefully, this won’t be the case.

Elections in Georgia Mark a Clear Negative Trend

Given the Georgian Dream party’s recent policies that some compared to Russian-style “foreign influence” laws, how do you see these laws affecting civil society and independent media in Georgia, and are they part of a larger autocratic trend?

Professor David Aprasidze: Absolutely. I am quite certain that this is part of a larger autocratic trend, unfortunately. We saw signs of this when the law was introduced in the spring, just a few months before the elections, and have since witnessed further deterioration. Although there were critical voices and warning signs that the elections would deal another blow to democracy, it is now clear that this decline has continued following the adoption of this law.

The elections demonstrated a decline in the quality of democracy in Georgia, marking a clear negative trend. Will this go further and have a tangible impact on civil society and the media? That remains to be seen. However, if the current trend persists, we can expect Georgian media and civil society to face increased pressure in the coming days and weeks.

Firstly, we see a clear trend of deterioration. Secondly, with the law’s provisions soon to be implemented, if these are fully enforced by the relevant authorities, they will certainly shrink the space for civil society, limit access to independent funding, and may soon lead to a significant reduction in the number of independent media outlets and non-governmental organizations.

The European Commission has stated that it cannot recommend EU membership talks unless Georgia changes course. What specific changes do you believe the Georgian government would need to make to regain the EU’s confidence, and how likely are such reforms under the current/new administration?

Professor David Aprasidze: Unfortunately, I, along with many observers of Georgia, believe that under the current government or administration, it is very hard to imagine a restart of relations with the EU.

When the European Commission issued the requirements—known as the “9 steps”—for Georgia to progress toward membership, they were very specific about opening negotiations. The most important of these 9 points was free and fair elections, with an expectation for Georgia to conduct elections that are free, fair, and competitive. Now, we see those leading countries in the European Union, except Hungary (due to similarities in populist governance between Georgia and Hungary), have condemned the way the elections were organized and held in Georgia. They demand that the Georgian government fully investigate all the irregularities observed both on election day and beforehand.

However, we do not see any signs that the Georgian authorities are prepared to meet this requirement. Therefore, I do not expect that Georgian authorities will be ready to meet the other 8 requirements set by the European Commission. While Georgian authorities officially continue to argue that Georgia is still on the path to integration, the reality and evidence are quite limited. Thus, I do not expect, unless there is a comprehensive change in administration or policy, that these authorities are prepared to make the necessary changes.

Georgian Dream’s Shift to Far-Right Rhetoric Derails Path to EU Integration

How do recent allegations of electoral fraud and interference reflect broader trends of democratic backsliding in Georgia, and what role does populism play in reinforcing this shift?

Professor David Aprasidze: Well, absolutely. We have already talked about the irregularities during elections, and this is an unfortunate confirmation, a proof that Georgia is backsliding on its path of democratization. Actually, Georgia has never been a fully functioning, consolidated democracy. It was moving along a difficult path toward democratization, but now we are undermining all the achievements we have made along the way. Therefore, these elections were a very strong and significant step backward.

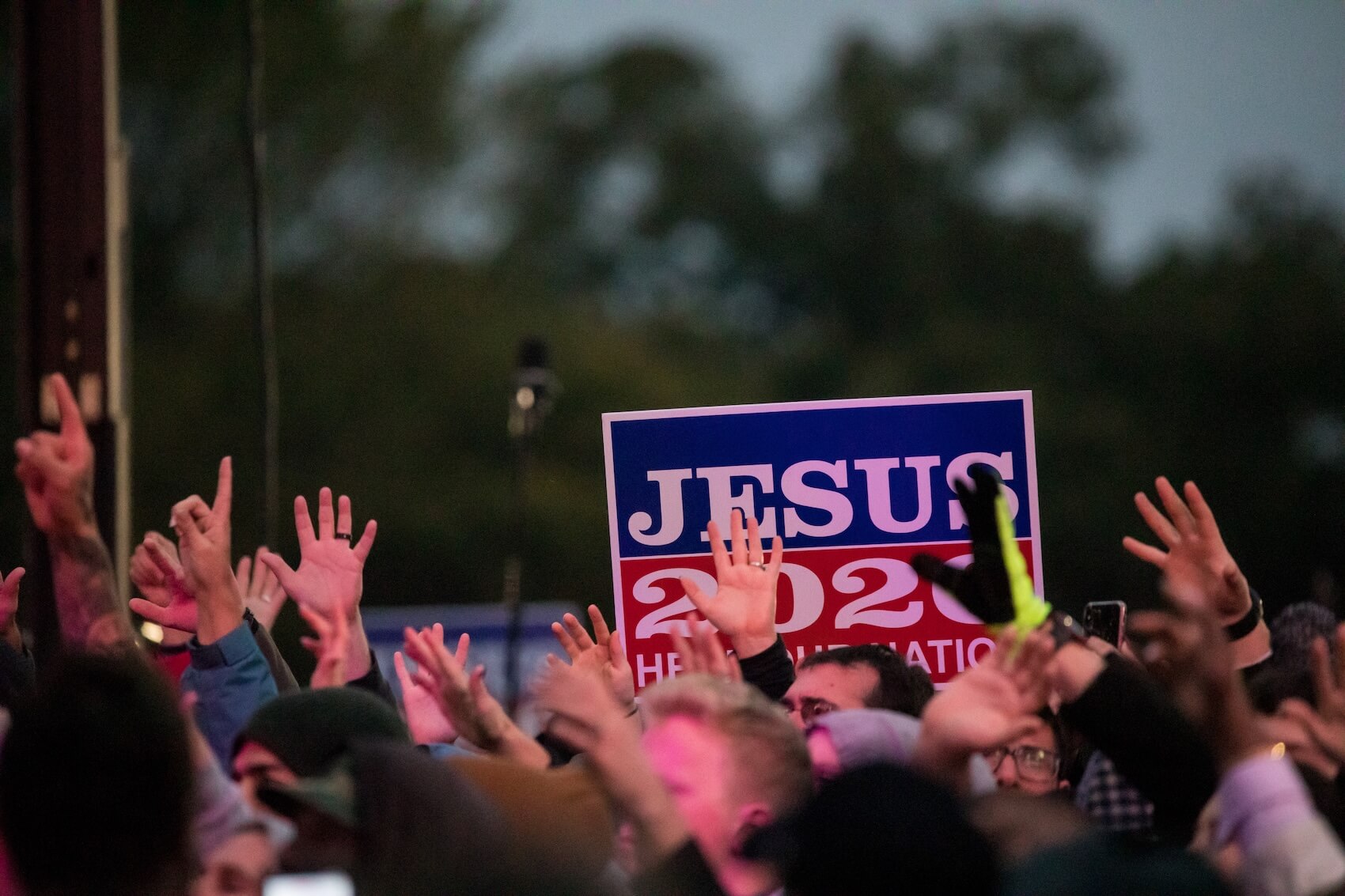

Populism—we initially discussed technocratic populism, right? Until around 2022, Georgian Dream exemplified this type of populism, emphasizing expertise and claiming to run the country like a successful business. However, since 2022, especially during the election campaign, we have seen a complete reshaping of this populist narrative. It has shifted toward a far-right, extreme position rooted in traditional values. While I have nothing against family values, this far-right approach frames family and religion in an anti-minority, anti-liberal context, openly attacking liberal values, including the protection of individual and minority rights. This shift from a purely technocratic populism to a far-right, anti-Western, anti-liberal rhetoric has become an important ingredient of Georgian Dream’s electoral campaign. This departure is why Georgian Dream has moved the country so far from its European integration trajectory, and it’s why I believe it’s simply impossible to restart the relationship between Georgia and the European Union under the current administration.

Hungary’s Populist Playbook Guides Georgian Dream’s Strategy

And lastly, David, Hungarian Prime Minister and the term president of European Union Victor Orbán visited Tbilisi and congratulated the leaders of Georgian Dream for their success while other EU’s leading officials criticized the election process. What sort of relationship does Georgian Dream have with Victor Orbán’s Fidesz Party in particular and with other far-right, populist parties in Europe?

Professor David Aprasidze: When Georgian Dream first embarked on its European trajectory, it joined the European Socialists as an observing member, initially positioning itself on the center-left of the ideological spectrum. However, especially after the war in Ukraine—partly due to geopolitical factors but, I believe, primarily due to domestic political motives and a desire to consolidate power—they quickly shifted toward the far right.

They aligned with and engaged in an exchange of ideas with Hungary’s Fidesz Party, and with Viktor Orbán in particular. Numerous mutual meetings took place; the Georgian Prime Minister met with Hungarian leaders multiple times, and Orbán visited Georgia. These exchanges occurred at various levels—parliamentary and party—making Hungary and its leadership Georgian Dream’s most reliable, if not only, partners in Europe.

Interestingly, if we trace the transformation of Fidesz and the evolution of Orbán himself—from the start of his political career to his current stance—it serves as a model for Georgian Dream. To answer your question directly, Orbán is a close ally and influential mentor to Georgian Dream. The Hungarian model of populist transformation, led by Fidesz, provides Georgian Dream with a playbook on how to proceed.