Please cite as:

Oblak Črnič, Tanja & Koren Ošljak, Katja. (2024). “Digital Strategies of Political Parties in the 2024 European Elections: The Case of Slovenia.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0083

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON SLOVENIA

Abstract

This report offers a systematic analysis of Slovenian political parties in online campaigning during the 2024 EP elections. It draws on a dataset of political parties and their online representations, selected from official party websites and dominant social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram and TikTok, in May 2024. The results show that Slovenian parties’ communication during the 2024 EP campaign was quite self-referential, accompanied by images of the candidates, indicating a high degree of personalization of politics. Moreover, the results show the “non-European orientation” of the campaign, as domestic issues dominated the parties’ social media profiles and websites. Furthermore, the content analysis of the parties’ websites revealed five issues where some cross-party differences in attitudes were observed: 1) agreement in party attitudes towards the environment; 2) on Ukraine and Palestine, parties on the right took different positions; 3) the centre-left coalition supported the government’s domestic policy the most; 4) right-wing actors tended to frame migration and minority rights in a restrictive way; actors with a left-wing orientation took a more humanitarian approach; and 5) left-wing actors were most tolerant vis-à-vis gender and reproductive rights. The results, therefore, imply a clear distinction between Slovenian parties of the left and right during the 2024 EP campaign.

By Tanja Oblak Črnič* & Katja Koren Ošljak* (University of Ljubljana)

Introduction

Many studies over the last two decades have confirmed how the internet and social media have changed the conditions of political communication (Blumer and Kavanaugh 1999). Some argue that media changes are radically shaping the conditions of political communication (Chadwick, 2023; Kreiss, 2023). Chadwick (2023: 21) argues that a hybrid media system is a more fluid and contested space than previous mass media systems. These shifts are evident during election campaigns, which are characterized by computational politics (Tufekci, 2014).

The data collected during the formal campaign for the 2024 European elections describe the primary digital strategy of Slovenian political parties and a brief comparison of the selected strategies during the EP campaign. The question is, therefore, how candidates and their parties present themselves in these digital presentations, how they address their potential voters, what messages they use to occupy the digital channels they manage, and with what degree of communicative responsibility they engage with citizens.

First, we analysed their landing pages to identify ideological identifiers and several other issues that could indicate the national or European orientation of the parties. We then focused on identifying the main issues included in their campaign as potential indicators of a propensity towards populism and the attitudes of the observed parties towards selected public issues such as climate change, rights of the LGBTQ+ community, human rights of migrants and other minorities, national government policies, violence against women, abortion and reproductive rights, and gender and sexual identity. In addition to these “identity policy orientations”, we also looked at the extent to which each party focused on the wars in Ukraine and Palestine. The main findings are placed in the context of the critical role of social media in so-called data-driven campaigning (Chadwick and Stromer-Galley, 2016).

Research design, methods and sample

The analysis of the online presence of Slovenian political actors has a long history (see Oblak, 2003; Oblak and Željan, 2007; Oblak and Ošljak, 2013; Oblak, 2017). For this report, we have chosen a quantitative approach with mainly descriptive aims regarding the communicative characteristics of the selected political actors within a case study: the 2024 European elections. The data were collected using the content analysis method: an extended set of variables was constructed, in which we revised the instrument used in the Digital Citizenship project (see Oblak, 2016). The data, which was collected on the websites of political parties and social media profiles, allowed for the relatively easy identification of several pieces of information. The data collection was part of the assignments within the undergraduate course on Politics and Digital Culture at the University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Social Sciences.

We have analysed the websites of the six Slovenian parties that officially entered the 2024 European elections: three of them – Gibanje svoboda (GS), Levica (LP), and Socialni demokrati (SD) – belong to the ruling coalition government, while Nova slovenija (NS) and Slovenska demokratska stranka (SDS) were political parties in opposition. Thus, the majority of analysed parties were campaigning as Slovenian parliamentary parties. In addition, we analysed the online presence of Vesna–zelena stranka (green party), which competed as a nonparliamentary party. Regarding their associations with political groups in the European Parliament, 38% belong to the European People’s Party (EPP), 15% to the Socialists and Democrats (S&D), another 15% to the liberal Renew Europe and 15% to the Left.

Table 1: Results of the 2024 EP elections in Slovenia

| National political parties | Vote share (%) |

| [Right] SDS–Slovenska demokratska stranka | 30.59 |

| [Centre] Svoboda!–Gibanje svoboda (GS) | 22.11 |

| [Centre] Vesna–Vesna–zelena stranka (green party) | 10.53 |

| [Left] SD–Socialni demokrati | 7.76 |

| [Right] N.Si–Nova slovenija – Krščanski demokrati (NS) | 7.68 |

| SLS–Slovenska ljudska stranka | 7.21 |

| [Left] Levica–Stranka levica (LP) | 4.81 |

| Resni.ca–Državljansko gibanje Resni.ca | 3.97 |

| DeSUS–DD–Coalition DeSUS–DD (Demokratična stranka upokojencev Slovenije, Dobra država) | 2.22 |

| ZS–Zeleni slovenije | 1.61 |

| Druge stranke–Druge stranke | 1.52 |

| Total | 100 |

Political actors’ online presence during the EP election campaign

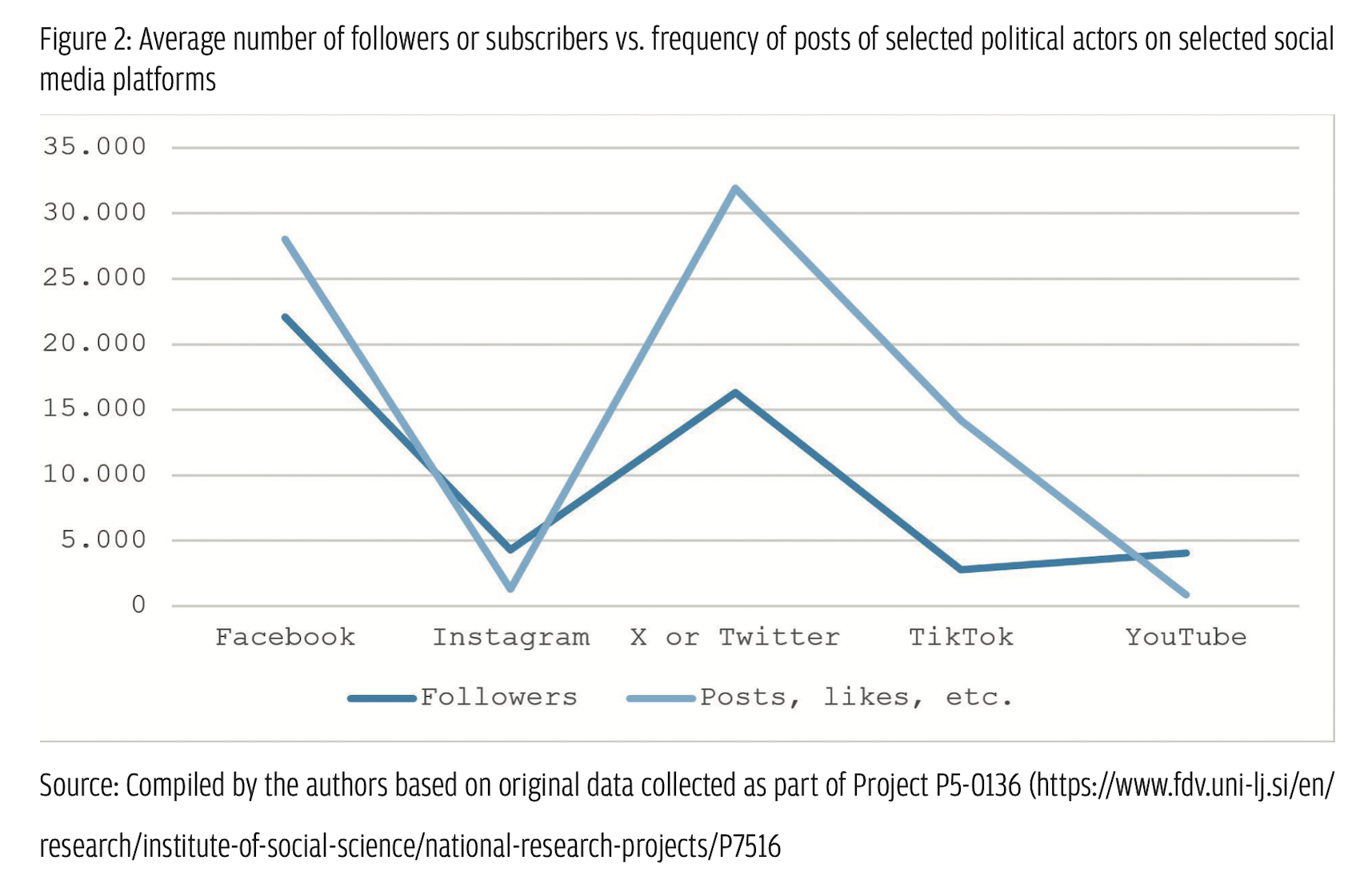

According to preliminary data, our analysis of the online presence of parliamentary parties and selected nonparliamentary candidates for the European elections (e.g., Vesna) shows that all actors were present on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube, while some of them also promoted themselves on X/Twitter and TikTok (see figure 1). However, their activity and visibility on these networks varied considerably. For example, on average, the number of followers or subscribers to the most present social media was highest on X, followed by Facebook and TikTok (see figure 2).

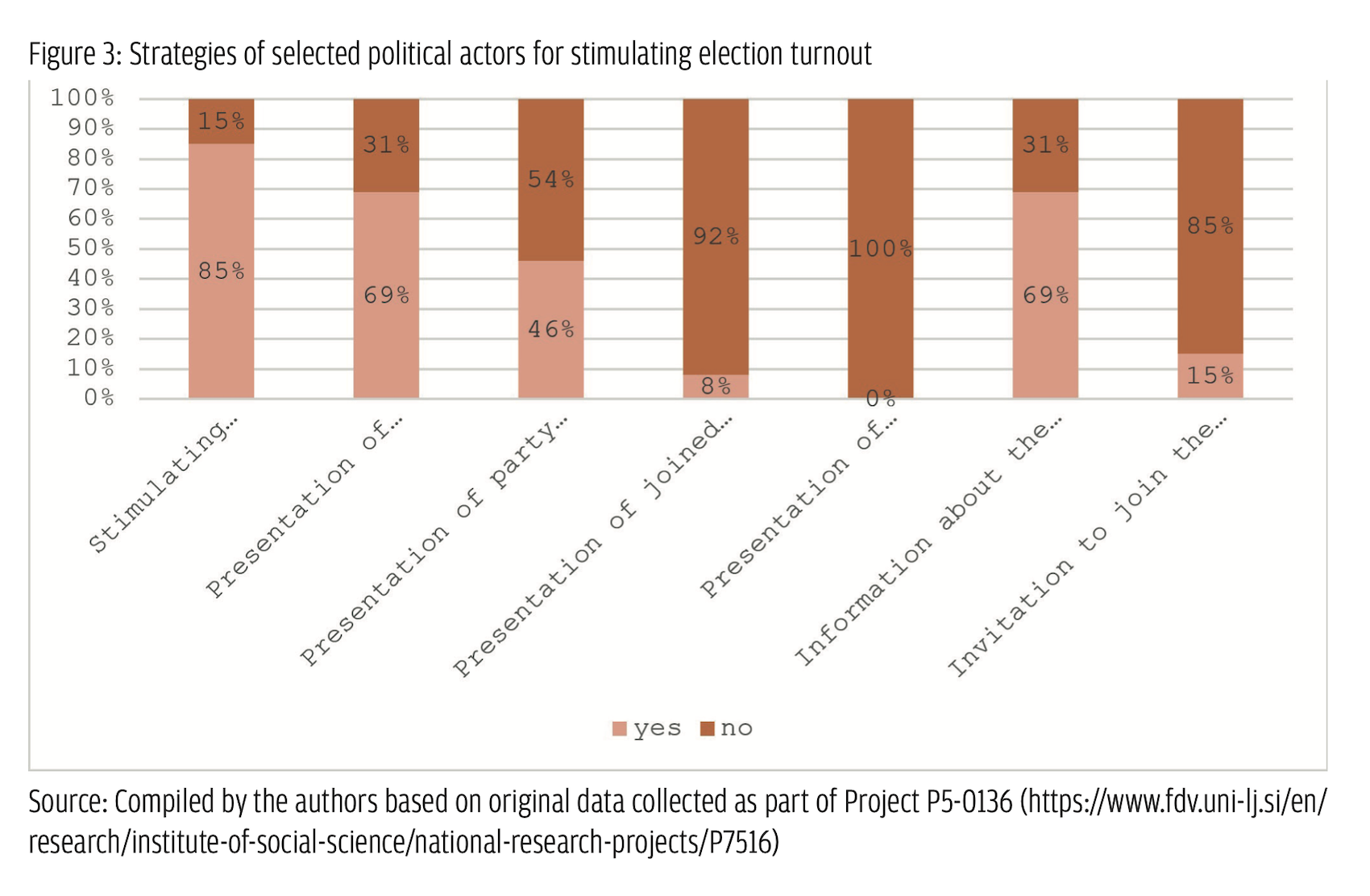

However, the online political landscape during the 2024 EP election campaign was more diverse in terms of the forms of participation on social media and the thematic focuses they gave their attention to. The data shows (see figure 3) that while direct invitations to vote dominated, immediately afterwards, the focus shifted to candidate presentations and information about their visits “on the ground”. This trend is a long-standing one in conventional digital campaigns, and it would be hard to call the 2024 campaign an outlier. It is also evident that Slovenian political parties were not very well placed in the European context, nor did they provide information on which EP group they belong to and with whom they are aligned.

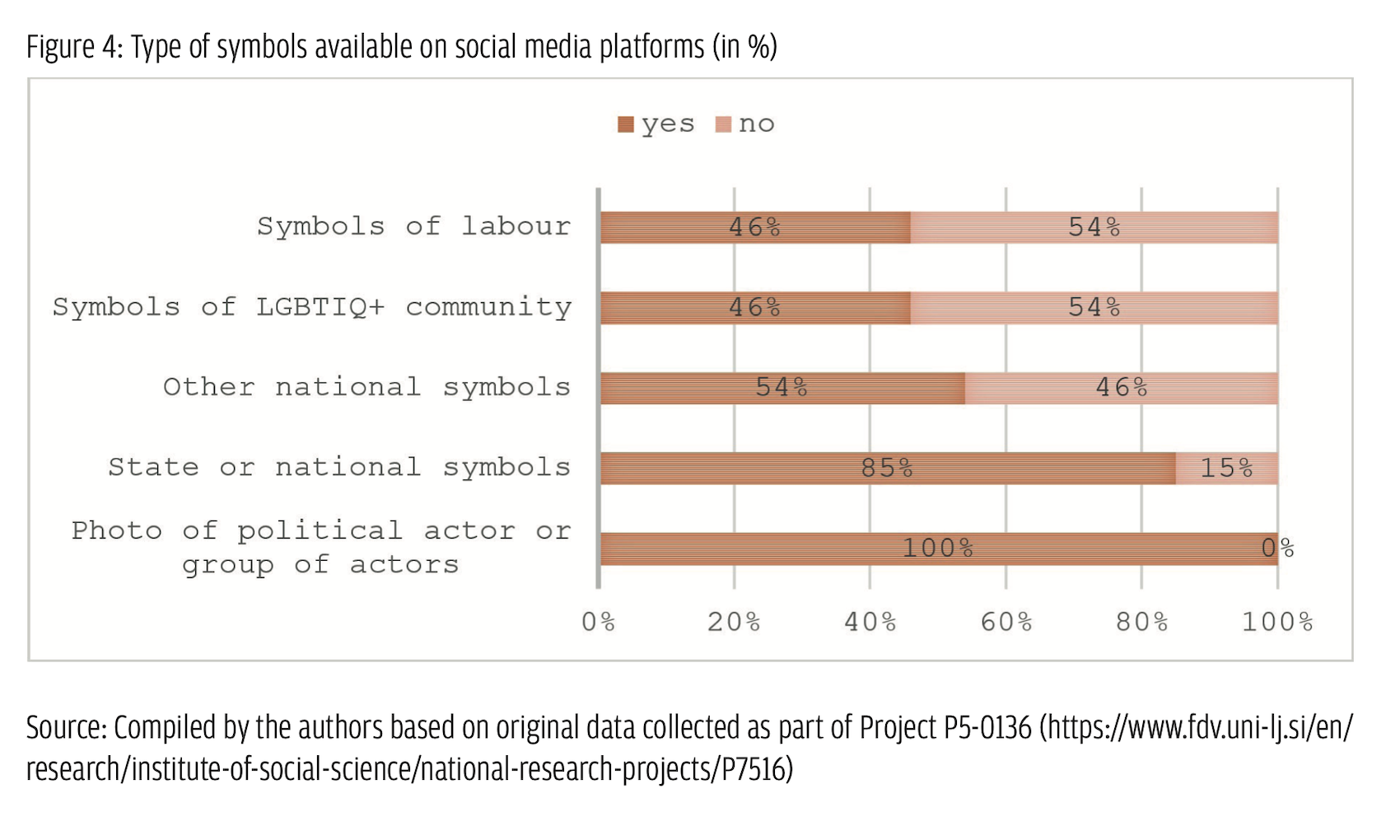

Such “self-referential coverage”, regularly accompanied by photos and videos of the candidates, is another familiar step towards a strong personalization of politics, which is at the same time distinctly local and pragmatic: rather than a concrete commitment to something, the focus is mainly on a specific political figure and his or her activities. As a result, we looked at what kind of symbols are most present in social media profiles, especially to see if there is a common logic in such election campaigns (see figure 4).

The main topics and political parties’ attitudes towards political issues

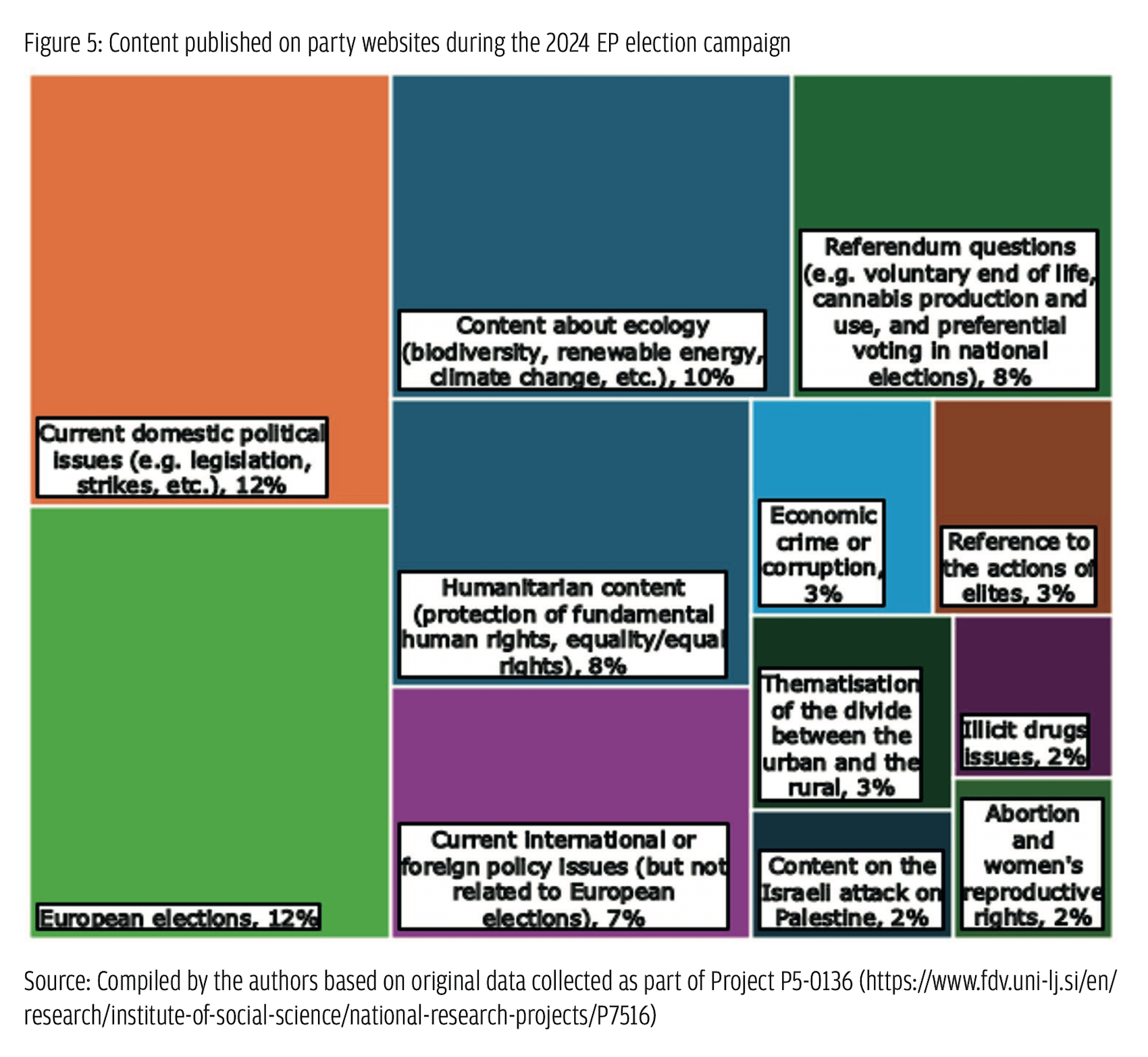

The data suggest that the “non-European orientation” of the campaign was at least partly reflected in attitudes to pressing issues: the parties’ social media profiles and websites were dominated by domestic issues, followed by ecology and climate change; there was also a strong presence of referendum issues and issues related to women’s reproductive rights (see figure 5).

In order to explore the attitudes of Slovenian political parties in their campaigns for the 2024 EP elections, the websites of the six political parties were also monitored. We were interested in whether and how they positioned themselves on the nine selected issues, which we used as indicators of potential biases. We also observed and coded cases where a particular issue was not present on the website.

In the analysis, the six campaigning parties were paired into three general categories of the political spectrum: 1) the right (Nova Slovenija and Slovenska demokratska stranka), 2) the centre (Gibanje Svoboda and Vesna–zelena stranka) and 3) the left (Levica and Socialni demokrati). In cases where the attitudes of two parties from the same part of the political spectrum were coded in different categories, both categories were marked (see table 2).

Table 2: Attitudes of Slovenian political parties towards the political issues

| 1) Ecology. When the topic of ecology or climate change appears on the website, how is it addressed? | ||||

| Parties | Denial | Neutral | Awareness | Not present |

| Right | + | + | ||

| Centre | + | |||

| Left | + | |||

| 2) Ukraine. When the topic of the war in Ukraine comes up on the website, how is it handled? | ||||

| Parties | Pro-Russia | Neutral | Pro-Ukraine | Not present |

| Right | + | + | ||

| Centre | + | + | ||

| Left | + | + | ||

| 3) Palestine. When the topic of Palestine appears on the website, how is it addressed? | ||||

| Parties | War, genocide | Neutral | Israeli defence | Not present |

| Right | + | |||

| Centre | + | + | ||

| Left | + | |||

| 4) Government. When the government of the Republic of Slovenia topic appears on the website, how is it treated? | ||||

| Parties | Critically | Neutral | Supportively | Not present |

| Right | + | |||

| Centre | + | + | ||

| Left | + | |||

| 5) Human rights. When the topic of human rights (i.e., minorities or migrants) is raised on the website, how is it addressed? | ||||

| Parties | Restrictive | Neutral | Supportive | Not present |

| Right | + | |||

| Centre | + | |||

| Left | + | + | ||

| 6) Abortion. When the topic of abortion rights or reproductive rights is raised on the website, how is it addressed? | ||||

| Parties | Against | Neutral | Pro | Not present |

| Right | + | |||

| Centre | + | |||

| Left | + | |||

| 7) Violence against women. When the topic of violence against women appears on the website, how is it addressed? | ||||

| Parties | Not a problem | Neutral | As a problem | Not present |

| Right | + | + | ||

| Centre | + | + | ||

| Left | + | |||

| 8) LGBTIQ+. When the topic of the LGBTIQ+ community appears on the website, how is it addressed? | ||||

| Parties | Restrictive | Neutral | Supportive | Not present |

| Right | + | + | ||

| Centre | + | |||

| Left | + | |||

| 9) Gender equality. When the topic of gender equality or gender identities is raised on the website, how is it addressed? | ||||

| Parties | Restrictive | Neutral | Supportive | Not present |

| Right | + | |||

| Centre | + | |||

| Left | + | |||

What can such results tell us about the parties’ attitudes to a selected set of public and political issues?

- Environmental issues: According to the results, political actors seemed to be most united in their attitudes towards environmental crises or ecological issues. However, one of the actors from the right differed significantly in this respect, expressing the irrelevance of environmental problems.

- War and conflict: Regarding the war in Ukraine, there is no dilemma that Slovenian political actors expressed pro-Ukrainian positions during the election campaign, or in this case, Russia was seen as the war aggressor. However, it is worth noting that the war in Ukraine was not an issue on 50% of the parties’ websites during the same period. Although Palestine is also an armed conflict, the results suggest a different picture: right-wing parties raised the issue of Israel’s right to self-defence. Left-wing parties, on the other hand, reported more on the war and genocide against the Palestinians.

- Domestic politics: Given the centre-left government coalition, the attitude of the political parties towards the government’s work is not surprising: the right-wing actors were critical, while the left and centre were supportive. The only exception was the Green Party Vesna, which is not part of the current coalition and did not comment on the government’s work on its website during this election campaign.

- Human rights and minorities: Human rights, especially in relation to minorities and migrants, were also a divisive issue for political parties during the European election campaign in Slovenia. Right-wing actors framed the issue of migration and minority rights in more restrictive terms, while centre-left and left-wing parties adopted a more humanitarian approach in their reports.

- Gender and reproductive rights: The issue of gender and women’s reproductive rights draws an even sharper line between the anti-abortion right and the rest: the political centre and the left defend women’s right to decide about their bodies. A different picture emerges in the case of violence against women, which is addressed as a problem by actors across the political spectrum: here, one centre-right and one right-wing actor did not address the issue on their websites during the 2024 election campaign. However, positions on gender justice and (non-binary) gender identities shifted this logic again: The websites of the right-wing political actors were similarly restrictive, while the left explicitly supported gender equality; the political parties of the centre seemed to avoid such issues on their websites during the EU election campaign.

Attitudes of young citizens towards the personalization of politics during the EP campaign

Based on the preliminary results of our datasets on the online presence of Slovenian political parties in the run-up to the 2024 European elections, we found a marked personalization of the campaign, where candidates’ personal profiles can have a significantly higher reach than parties’ profiles. We also found that parties often resort to populism, either based on the othering of minorities and foreigners and the division between ‘us and them’ or on the glorification of tolerance and inclusive discourse.

The analysis also shows a strong tendency for parties to use a more personalized campaign, where candidates’ personal profiles can have a much wider reach than party profiles. Furthermore, reflecting on the analyses from the perspective of the students who collected the data as part of the course, their reflections were quite common: they strongly agreed that political parties do not adequately address them in the campaign. For example, they noted that the parties mainly appealed to young people to participate in the elections, while at the same time, there were very few young people on the lists of candidates, who were also mostly placed at the back of the queue.

Students also criticized the patronage of political parties that do not communicate transparently during election campaigns. They added that their publications were not informative, their positions were not sufficiently argued, etc. Among the issues that were very important to young people but not well covered by the parties, students highlighted the war in Ukraine, the genocide in Palestine, human rights, migration and climate change.

(*) Tanja Oblak Črnič is professor of Communication Studies at the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana and a member of the research program Political Research (J5-036). Contact: tanja.oblak@fdv.uni-lj.si.

(**) Katja Koren Ošljak is an assistant and researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana. She is also finalizing her PhD in the reconceptualization of media education in the context of mediatized childhood. Contact: katja.osljak@fdv.uni-lj.si.

References

Blumler, J. G., & Kavanagh, D. (1999). The third age of political communication: Influences and features. Political Communication 16(3): 209–230, https://doi.org/10.1080/

105846099198596

Chadwick, A. (2013) The hybrid media system: Politics and power, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Chadwick, A. and Stromer-Galley, J. (2016) Digital media, power, and democracy in parties and election campaigns: Party decline or party renewal? International Journal of Press/Politics 21(3), pp. 283–294. DOI: 10.1177/1940161216646731

European Parliament (2024), Slovenia – Official results. Accessed 8 October 2024 from https://results.elections.europa.eu/sl/nacionalni-rezultati/slovenija/2024-2029/

Oblak Črnič, T. (2002) Dialogue and representation: Communication in the electronic public sphere. Javnost, 9(2): 7–22

Oblak Črnič, T. (2003) Boundaries of interactive public engagement: political institutions and citizens in new political platforms. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 8(3): 1–21. http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol8/issue3/oblak.html

Oblak Črnič, T. (2017). Neglected or just misunderstood?: The perception of youth and digital citizenship among Slovenian political parties. Teorija in praksa: revija za družbena vprašanja 54: 96–111

Oblak Črnič, T., & Koren Ošljak, K. (2013). Politically un-interactive web: Transformations of online politics in Slovenia. International Journal of Electronic Governance 6(1): 37–52.

Oblak Črnič, T., & Željan, K. (2007) Slovenian online campaigning during the 2004 European parliament election: Struggling between self-promotion and mobilisation. In: Kluver, R., Jankowski, N., Foot, K., and Schneider, S.M. (eds.), The Internet and national elections: A comparative study of web campaigning (pp. 60–76). London and New York: Routledge.

Tufekci, Z. (2014). Engineering the public: Big data, surveillance and computational politics. First Monday 9(7), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i7.4901

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON SLOVENIA