The fourth lecture of the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025 featured Professor Daniel Fiorino, a leading expert on environmental policy at American University. Professor Fiorino examined how right-wing populism—characterized by distrust of expertise, nationalism, and hostility to multilateralism—combined with entrenched fossil fuel interests to undermine climate mitigation efforts in the United States during the Trump administration. He highlighted the geographic and partisan divides that shape US climate politics and explained how Republican dominance in fossil fuel-dependent states reinforces skepticism toward climate action. Professor Fiorino’s lecture underscored the vulnerability of US climate policy to political polarization and partisan shifts, warning that right-wing populism poses an enduring challenge not only to American climate governance but to global efforts to address the climate crisis.

Reported by ECPS Staff

The fourth lecture of the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025, held online under the theme “Populism and Climate Change: Understanding What Is at Stake and Crafting Policy Suggestions for Stakeholders” (July 7–11, 2025), featured Professor Daniel Fiorino, one of the United States’ most respected scholars on environmental and energy policy. His lecture, titled “Ideology Meets Interest Group Politics: The Trump Administration and Climate Mitigation,” explored how right-wing populism and entrenched fossil fuel interests intersect to shape and undermine climate policy in the United States—a subject deeply relevant not only for US politics but for global climate governance more broadly.

Professor Fiorino is currently based at American University’s School of Public Affairs in Washington, DC, where he serves as the founding director of the Center for Environmental Policy. Prior to his academic appointment in 2009, he had a distinguished career at the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), where he worked in policy development and environmental governance. Professor Fiorino’s work is both theoretically rigorous and policy-relevant, addressing some of the most pressing governance challenges posed by the climate crisis.

His published books include Can Democracy Handle Climate Change? (Polity Press, 2018), which examines the compatibility of democratic systems with effective climate action; A Good Life on a Finite Earth: The Political Economy of Green Growth (Oxford, 2018), which explores pathways toward sustainable prosperity; and The Clean Energy Transition: Policies and Procedures for a Zero-Carbon World (Polity, 2022). Professor Fiorino is also currently writing a book on the evolution of the EPA, further cementing his authority on American environmental policy.

In this lecture, Professor Fiorino provided participants with a critical framework for understanding how the Trump administration became emblematic of the global rise of right-wing populism and its impact on climate policy. He contextualized his analysis by drawing attention to the defining characteristics of right-wing populism—namely, distrust of scientific expertise, skepticism of multilateralism, and nationalist economic priorities—and how these traits directly contradict the requirements for effective climate mitigation, which depends on science, international cooperation, and long-term policy consistency.

Through this lens, Professor Fiorino examined how the Republican Party’s longstanding relationship with the fossil fuel industry became fully aligned with right-wing populist ideology during the Trump years. His lecture traced not only the Trump administration’s concrete policy reversals—such as rolling back EPA regulations and undermining international climate agreements—but also the broader cultural and institutional dynamics that entrench resistance to climate action in the US.

Professor Fiorino’s contribution offered participants a nuanced and empirically grounded insight into one of the most acute cases of populism’s challenge to climate governance today, setting the stage for a wider discussion on how democratic societies can respond to these intersecting threats.

Trust in Government and Political Polarization

In his lecture, Professor Fiorino offered an incisive introduction to the political landscape surrounding climate change in the United States, situating it within broader international patterns. Professor Fiorino framed his presentation with a candid declaration of his own critical stance toward Donald Trump, whose administration he described as emblematic of right-wing populist dynamics globally.

Professor Fiorino began by outlining the structure of his talk, which sought to explain how ideology and interest group politics intersect in the US context, particularly around climate mitigation policy. He distinguished between left-wing populism—which tends to emphasize protection of vulnerable groups and acknowledges climate threats—and right-wing populism, which he characterized as deeply skeptical of climate science and resistant to mitigation policies.

A core theme of Professor Fiorino’s lecture was the alignment of the Republican Party with the interests of the fossil fuel industry. He argued that while this alignment has long defined Republican political economy, it is now reinforced by a populist ideology marked by distrust of expertise, nationalism, and hostility to multilateralism. This convergence of interests and ideology, Fiorino suggested, has resulted in a Republican Party that is uniquely resistant to climate action among conservative parties worldwide.

To illustrate this context, Professor Fiorino presented data on declining trust in government, highlighting that confidence in the US federal government fell from over 50% in the early 1970s—when foundational environmental laws were enacted—to approximately 20% today. This erosion of trust reflects a broader trend in Western democracies but is especially acute in the United States.

Professor Fiorino underscored that climate change has become a highly polarized political issue, with public concern split sharply along partisan lines. He noted that while general surveys might suggest widespread concern about climate change among Americans, this concern is overwhelmingly concentrated among Democrats and those who lean Democratic. By contrast, Republican voters and leaders exhibit skepticism toward climate policy and its scientific foundations. He illustrated this divide with historical data showing that partisan gaps on climate issues, which stood at approximately 36% around 2009–2010, had widened to over 50% in recent years.

Professor Fiorino traced this widening divide back to the 1990s and highlighted that, unlike their conservative counterparts in many other countries who acknowledge the necessity of climate action, Republican leaders in the US have cultivated or tolerated a strong climate denial movement. He emphasized that even when some Republican figures concede that human activity contributes to climate change, they often reject mitigation efforts as too costly or harmful to other national interests.

Professor Fiorino’s analysis portrayed a political environment in which climate and environmental issues have become deeply entangled in cultural and partisan identity. He argued that this entrenched polarization represents a significant barrier to effective climate policy, reflecting not just interest group influence but a broader ideological shift that has positioned climate skepticism as a core feature of right-wing populism in the United States.

Geography, Economy, and Political Alignment

Moreover, during his lecture, Professor Fiorino examined the intricate relationship between US geography, economic structure, and political alignment, especially as it pertains to climate politics. He traced a geographic realignment of American political parties over recent decades, emphasizing how the Northeast and West Coast have become reliably Democratic, while much of the South—including states that were part of the Confederacy—along with the rural Midwest and interior West, have become Republican strongholds. This realignment has contributed to the sharp partisan polarization around issues such as climate policy.

Professor Fiorino noted that this polarization has coincided with a growing identification of the Republican Party with specific economic sectors, particularly mining, energy, and farming. Drawing on the work of political scientist David Carroll, Professor Fiorino highlighted that by 2015, Republican representation of these sectors had markedly increased, deepening party-aligned divisions around resource development and climate mitigation. While elite polarization on climate issues began first among policymakers, Professor Fiorino explained that these divisions quickly diffused to the broader electorate, making attitudes toward climate action increasingly partisan.

A key insight from Professor Fiorino’s analysis concerned the connection between a state’s economic dependence on fossil fuels and its political attitudes toward climate mitigation. Though definitive causal studies remain limited, Professor Fiorino observed a clear pattern: states with economies heavily reliant on oil, gas, or coal—such as Texas, Oklahoma, West Virginia, Louisiana, Wyoming, and Alaska—have tended to lean strongly Republican and exhibit skepticism or hostility toward climate mitigation policies. Even among the top nine mining-intensive state economies identified in a Brookings Institution study, most are Republican-dominated and resistant to aggressive climate action.

Exceptions to this pattern, such as New Mexico and Colorado, underscore the complexity of regional politics. New Mexico’s large Native American and Latino populations, Professor Fiorino noted, contribute to its Democratic leanings despite its extractive economy. Overall, Professor Fiorino concluded that states’ economic dependence on fossil fuels is a powerful predictor of their political alignment and climate policy stance, reinforcing the geographic and partisan divides shaping US climate politics today.

Interest Groups and the Ideological Foundations of Right-Wing Populism

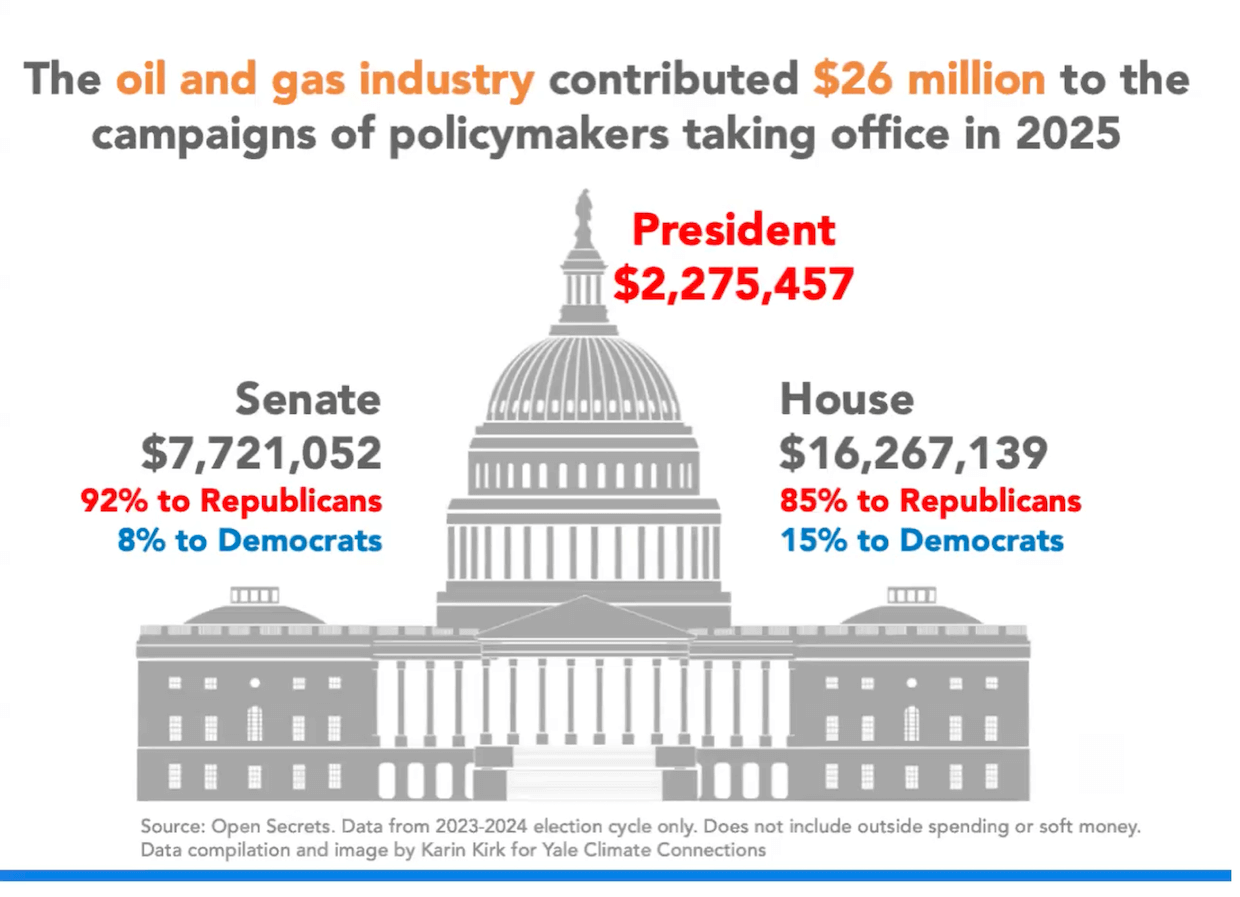

In his lecture, Professor Daniel Fiorino also examined how the intersection of interest group politics and right-wing populist ideology has shaped US climate policy, particularly during the Trump administration. Professor Fiorino began by noting that while scholars often overemphasize the role of campaign contributions in presidential politics, campaign finance remains a revealing indicator of partisan alliances. He pointed to data showing that during recent election cycles, approximately 92% of oil and gas industry contributions to US Senate campaigns and 85% to House campaigns went to Republican candidates, underscoring the fossil fuel sector’s deep alignment with the Republican Party.

Professor Fiorino then turned to the ideological features of right-wing populism and their relevance for climate politics. Drawing on his involvement in a special issue of Environmental Politics (2021–22), he identified three defining characteristics of right-wing populist movements: hostility toward elites and experts, skepticism of multilateral institutions, and a strong nationalist orientation emphasizing reliance on domestic resources. He explained that these attributes directly clash with the core requirements of effective climate action, which depend on scientific expertise and international cooperation to address a global challenge.

Professor Fiorino observed that the Trump administration embodied these populist traits, with President Trump declaring an “energy emergency” on his first day in office and promoting an aggressive policy of oil, gas, and coal development. Despite the irony that renewable resources such as wind and solar are also domestic, this nationalist framing ignored those alternatives in favor of traditional fossil fuels.

This ideological posture aligned seamlessly with the Republican Party’s long-standing alliance with the fossil fuel industry—a relationship further strengthened by geographic realities. Professor Fiorino explained that Republican political dominance is concentrated in states where fossil fuel extraction is economically significant, such as West Virginia and Wyoming (coal) and Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Alaska (oil and gas). These states have consistently resisted climate mitigation policies, reflecting both economic interests and the populist-nationalist narratives advanced by Republican leaders.

Finally, Professor Fiorino highlighted a key legal development shaping the regulatory framework for climate policy: the 2007 Supreme Court ruling in Massachusetts v. EPA, which established that greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide could be regulated under the Clean Air Act if found to endanger public health and welfare. Professor Fiorino warned that one priority of the Trump administration was reconsidering this “endangerment finding,” thereby undermining the scientific and legal basis for federal climate regulation—a testament to how deeply right-wing populist ideology and fossil fuel interests converged during this period.

The Trump Administration’s Climate Policy Record and Future Prospects

Professor Fiorino provided a critical overview of the Trump administration’s climate policy record, emphasizing its ideological and institutional efforts to roll back climate mitigation initiatives. Professor Fiorino began by highlighting the significance of the “endangerment finding”—a scientific determination under the US Clean Air Act that greenhouse gases pose a threat to public health and welfare. While the first Trump administration did not formally challenge this finding, Professor Fiorino noted that there is growing discussion within conservative circles about overturning it, a development that would severely undermine the federal government’s authority to regulate carbon emissions.

Professor Fiorino also discussed the social cost of carbon, a metric developed through interagency collaboration to quantify the economic harm of each additional ton of carbon dioxide emitted. Under Trump, this metric was effectively discarded: the interagency working group responsible for calculating it was disbanded, and agencies were directed to ignore it in decision-making processes. This represented a major departure from the approach of prior administrations, which had used the social cost of carbon as a benchmark for evaluating the benefits of climate regulations.

Another key policy reversal under Trump targeted the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which Professor Fiorino described as being under unprecedented assault, even more so than during the Reagan era. The Trump administration reconstituted the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, weakening the role of scientific expertise in policy evaluation, and sought to dismantle many components of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), despite the fact that more than 80% of the IRA’s benefits flowed to congressional districts represented by Republicans.

Professor Fiorino framed these developments within a broader pattern of policy oscillation, where President Obama had advanced climate action to the extent possible, only to see these efforts reversed by Trump, with Biden again reinstating them—illustrating a deeper challenge for US climate policy: the lack of consistency and durability.

Looking ahead, Professor Fiorino offered a sober assessment of prospects. He emphasized that while Donald Trump may eventually exit the political stage, the populist, anti-elite, and anti-science sentiments he amplified remain deeply embedded among American voters. This division is exacerbated by the United States’ closely balanced partisan coalitions and severe polarization, making sustained climate action difficult.

Professor Fiorino also noted that state-level policies matter but reflect this national divide: progressive states like California and New York continue to advance mitigation efforts, while roughly half of US states remain disengaged or actively opposed. He concluded by identifying the rise of right-wing populism as one of the principal threats to global climate action, warning that climate disruption itself could fuel political instability, including immigration pressures and social unrest, further complicating the path toward coherent climate governance.

Conclusion

Professor Daniel Fiorino’s lecture at the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025 offered participants an incisive and comprehensive analysis of the intersections between populist ideology, interest group politics, and climate policy in the United States. His examination of the Trump administration revealed how right-wing populism—characterized by distrust of expertise, nationalist rhetoric, and hostility toward multilateral governance—has compounded the Republican Party’s long-standing alignment with fossil fuel interests to obstruct meaningful climate action.

Professor Fiorino’s lecture illuminated the structural and ideological forces that have rendered climate change one of the most polarized issues in contemporary American politics. By contextualizing partisan divides within broader geographic and economic patterns—highlighting how fossil fuel-dependent states have become Republican strongholds skeptical of climate mitigation—he underscored that resistance to climate policy is not simply a matter of individual attitudes but is deeply embedded in economic structures and political identities.

A key takeaway from Professor Fiorino’s analysis is the vulnerability of US climate policy to abrupt reversals driven by partisan shifts. His account of the Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle environmental regulations, challenge the scientific basis for climate action, and undermine institutions such as the EPA illustrated the fragility of policy gains in the face of ideological polarization and institutional instability. Even major legislative initiatives like the Inflation Reduction Act, Professor Fiorino warned, remain at risk due to the cyclical nature of US partisan politics.

Looking forward, Professor Fiorino’s concluding reflections pointed to enduring challenges: while Donald Trump himself may eventually leave the political stage, the populist sentiments he amplified—skepticism of expertise, resentment of elites, and climate denial—remain entrenched among significant segments of the US electorate. This dynamic, coupled with a deeply divided federal landscape and uneven state-level engagement, poses significant obstacles to sustained and effective climate mitigation efforts.

In closing, Professor Fiorino emphasized that the rise of right-wing populism constitutes not only a domestic American challenge but also a global threat to coherent climate governance. His lecture provided participants with a sobering but necessary understanding of these intersecting forces, encouraging critical reflection on how democratic societies might navigate these headwinds to craft resilient and effective climate policy.