Giving an interview to the ECPS, Professor Francisco Rodríguez argues that today “Venezuela is no longer about Venezuela; it is about demonstrating power.” He reassesses Chavismo’s constitutional refoundation, noting that “not even the most hardline opponents of Chavismo question the Constitution today,” while stressing that redistribution collapsed when oil rents vanished: “The model of oil-rent redistribution simply does not work if there are no rents to distribute.” Professor Rodríguez highlights the durability of moral antagonism—“us versus them”—and shows how social policy can operate as rule: “We bring you food; we take care of your family’s needs.” Crucially, he links the post-Maduro landscape to Delcy Rodríguez’s room for maneuver, arguing that if she can claim Washington is no longer backing the opposition, she can frame Maduro’s seizure as “a strategic victory.” Yet he warns that US demands for “power-sharing with the opposition” would be “deeply problematic for Chavismo.” He concludes that Trump’s approach is transactional: “not demanding political reform… [but] asking Venezuela to sell oil.”

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

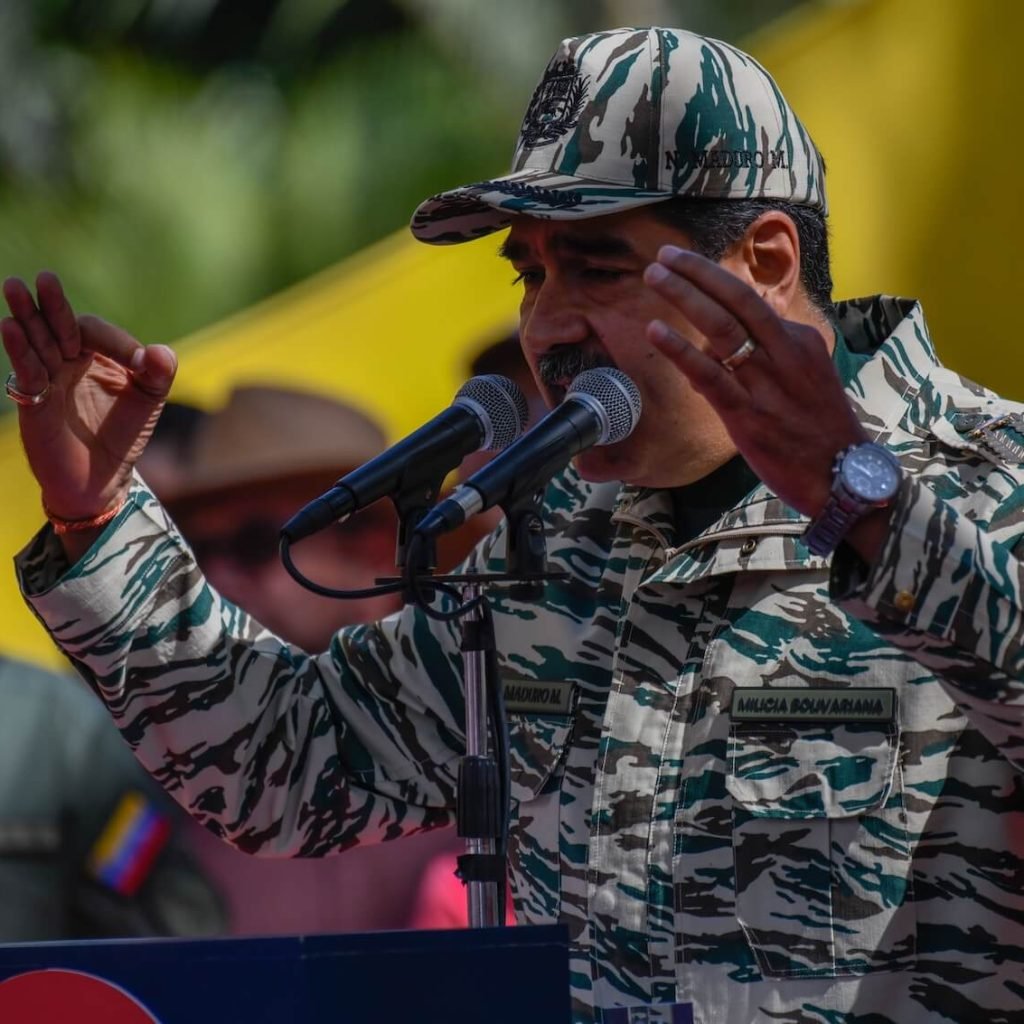

Giving an interview to the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Francisco Rodríguez—Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and Faculty Affiliate at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies—offers a comprehensive analysis of Venezuela’s post-Maduro political trajectory. Situating the case at the intersection of populist state resilience, authoritarian adaptation, and shifting US power strategies, Professor Rodríguez advances a stark diagnosis: “Venezuela is no longer about Venezuela; it is about demonstrating power.” In his account, the country has become a geopolitical signal—a site through which coercive capacity, transactional hegemony, and the limits of democratic opposition are being tested.

Professor Rodríguez begins by reassessing the foundational pillars of the Chávez-era project—constitutional refoundation, oil-rent redistribution, and the moralization of politics—arguing that these were not merely leader-centered strategies but elements of a durable populist state architecture capable of surviving leadership decapitation. While personally critical of the 1999 Constitution, he notes that “not even the most hardline opponents of Chavismo question the Constitution today,” underscoring how deeply constitutional refoundation has been absorbed into Venezuela’s political ethos. Even critics, he observes, now invoke the Constitution “as a model that the Maduro government is failing to uphold.”

On political economy, Professor Rodríguez emphasizes that populist redistribution depends on material abundance. “The model of oil-rent redistribution simply does not work if there are no rents to distribute,” he argues, pointing to a 93 percent collapse in oil revenues between 2012 and 2020. This collapse, compounded by US sanctions, forced the regime toward pragmatic—and even neoliberal—adjustments, not as a matter of ideological conversion but constraint. As Professor Rodríguez puts it, the economy remained closed “not because the government didn’t want it open, but because the United States government didn’t allow it.”

A central theme throughout the interview is the durability of moralized politics. Chavismo’s framing of politics as an existential struggle between “the people” and apátridas (stateless persons in Spanish/Portuguese, S.C) continues to structure both regime and opposition behavior. Professor Rodríguez cautions that this antagonistic grammar cannot be easily abandoned, particularly because “the opposition has also embraced a moralized framework, albeit from the opposite angle.” This mutual entrenchment helps explain why moments that might have enabled institutional cohabitation—most notably the opposition’s 2015 parliamentary victory—instead produced escalation and breakdown.

Within this transformed landscape, Professor Rodríguez devotes particular attention to Delcy Rodríguez’s room for maneuver. He argues that her political viability now hinges on whether she can credibly claim that Washington is no longer backing the opposition. Under those conditions, Maduro’s seizure can be reframed as “a strategic victory,” preserving Chavismo’s narrative of confrontation. At the same time, Professor Rodríguez warns that any US demand for “power-sharing with the opposition” would be “deeply problematic for Chavismo,” requiring a fundamental rewriting of its moral and institutional grammar.

The interview culminates in Professor Rodríguez’s assessment of US intervention under Donald Trump. Contrary to expectations, Trump did not demand democratization or power transfer, but oil. “What Trump is effectively doing now is not demanding political reform,” Professor Rodríguez explains; “he is asking Venezuela to sell oil to the United States.” This approach reflects a broader logic of informal empire: “It is more efficient to rule through domestic elites who follow US directives than to administer the country directly.” In this sense, Venezuela becomes less a national case than a global message—one that signals the new rules of transactional power, and the risks they pose for democratic oppositions worldwide.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Francisco Rodríguez, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

Between ‘Us Versus Them’ and External Power: Chavismo After Maduro

Professor Francisco Rodríguez, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start with the first question: With Nicolás Maduro removed yet the Chavista state apparatus largely intact, how should we reinterpret the foundational choices of the Chávez era—constitutional refoundation, oil-rent redistribution, and the moralization of politics—as elements of a populist state project capable of surviving leadership decapitation?

Professor Francisco Rodríguez: First of all, thank you very much for having me, and thank you for the opportunity to have a conversation about Venezuela and its populist model and evolution. Let me start by addressing the three aspects you mention. One of them is the Constitution. To a certain extent, constitutional refoundation is something Chavismo achieved quite remarkably, and it has become deeply ingrained in the Venezuelan ethos. The evidence for this is that there is very little, if any, discussion among Venezuela’s political actors about the need to change the Constitution. This is not to say that I think the current Constitution is good. On the contrary, I am quite critical of the way it expands executive power, and I believe that reform in this area will be necessary. But the reality is that not even the most hardline opponents of Chavismo question the Constitution today. In fact, they often invoke it as a model that the Maduro government is failing to uphold.

Turning to the other two points you raised—moralization of politics and oil rents—I think what we have seen over the past few years, roughly over the past decade, is that the model of oil-rent redistribution simply does not work if there are no rents to distribute. In Venezuela, those rents effectively disappeared. Oil revenues declined by 93 percent between 2012 and 2020. They have recovered somewhat since then, but they remain around 75 percent lower than their peak in 2012. As a result, the government has far fewer resources to redistribute, and, to some extent, it has already been forced to move toward a neoliberal policy paradigm. The main reason it has not gone further in that direction is that the economy has been under sanctions, which has prevented the implementation of some basic elements of the neoliberal model, such as opening the economy to foreign investment. This closure was not due to a lack of willingness on the government’s part, but rather because the United States government did not allow it.

Moralized Politics, External Pressure, and Strategic Uncertainty

This brings us to the third point: the demoralization of politics. This is something Chavismo will have to grapple with and much depends on how the current intervention evolves. Chavismo’s narrative has long been one of moralization—of us versus them—casting its opponents as apátridas, people without a sense of the fatherland. This narrative was effective over the past decade, during a period of open confrontation with the United States. But what has happened now is that the US has prevailed, in the sense that it has imposed its power on Venezuela and compelled Venezuelan authorities to react according to its dictates. Venezuelan authorities are therefore no longer acting autonomously. How do they sustain this narrative under these conditions? In the two weeks since Maduro’s seizure, they have been playing a dual game: complying with US demands while simultaneously maintaining the narrative that Maduro has been kidnapped and must be returned. In this way, they can still preserve the idea of confrontation.

The problem—and we will probably return to this later—is that this confrontation has its own dynamics. It is not something Chavismo can easily abandon, because the opposition has also embraced a moralized framework, albeit from the opposite angle: an “us versus them” discourse that pits the good against the bad, or decent society against a corrupt criminal mafia. This is not a narrative that can be changed at will. Yet if, for example, as a White House spokesperson suggested —and as President Trump has hinted—a White House visit by Delcy Rodríguez is being contemplated, it will become very difficult to sustain that confrontational narrative.

This leads to the final question: is there a way for Chavismo to continue evolving, and what will its core narrative be? Is this a strategic retreat—a case of “we have to do this to defend the project”? Or does it mean abandoning some of the project’s foundational tenets altogether?

It Is Too Early to Tell Whether Adaptation Will Become Strategy

In your work, you highlight how Chavismo constructed politics as a moral antagonism between “the people” and existential enemies. After Maduro’s seizure, does this moralized populist logic appear less as a contingent discursive strategy and more as a durable institutional grammar that shaped courts, security forces, and rent allocation?

Professor Francisco Rodríguez: I am tempted to respond as Zhou Enlai is said to have responded to a question about the French Revolution: it is too early to tell. It later emerged that the question was lost in translation and was actually about the May ’68 revolts, but the answer certainly applies here as well. What we are seeing now is very short-term adaptation to external circumstances, which, depending on how events unfold, may later be interpreted as strategic. Let me illustrate this with the example of Chávez after the 2002 coup.

After returning to power following the 2002 coup, Chávez adopted a very conciliatory tone. He even asked for forgiveness for his previous attitude, acknowledging that he should not have fired the PDVSA (Venezuela’s state oil company) managers in the manner he did—an episode widely perceived as humiliating, or at least framed that way by Chávez himself. Crucially, at that moment he also acceded to the main demand of economic elites: changing the economic cabinet. He brought in a group of pragmatists to run the economy, and they remained in place for about a year. One year later, however, Jorge Giordani—Chávez’s chief architect and ideologue—was back in charge of economic policy.

Some interpret this episode as Chávez merely playing along, and there is certainly some truth to that. But there is also another dimension, linked to the enduring dynamics of confrontation. That economic cabinet survived through the general strike and the oil strike against Chávez and was only replaced once Chávez concluded that he was back in confrontation mode—that the opposition was again trying to overthrow him—and that he therefore needed a command economy capable of asserting control over oil resources. This entailed abandoning efforts to accommodate the private sector. If we look back at that moment, Chávez imposed exchange controls in January 2003 during the oil strike, but crucially, he did not lift them once the strike ended. In effect, he shifted from a strategy of trying to bring the private sector into a governing coalition and broadening his base of support to one centered on confrontation: controlling oil rents and disciplining the private sector through control of those rents and access to foreign exchange.

Trump Is Not Demanding Reform—He Is Asking for Oil

One of the key uncertainties today is how the United States will proceed. US policy will shape many of the constraints facing Venezuela. If the US were to station warships off Venezuela’s coast and dictate terms, Venezuela would have little room to maneuver. But this is a somewhat unusual version of coercion coming from the Trump administration. President Trump’s first administration was the one that stopped buying oil from Venezuela. What Trump is effectively doing now is not demanding political reform, elections, or the transfer of power to María Corina Machado. Instead, he is asking Venezuela to sell oil to the United States—something Venezuelan authorities had long been asking Trump to permit. This is not a demand that makes the Delcy Rodríguez regime uncomfortable.

To the extent that Venezuelan authorities can establish a working relationship with the Trump administration, and as long as Washington maintains this stance, the moral and institutional grammar you describe is likely to persist. This episode can easily be framed as yet another chapter in the “us versus them” struggle. It is important to recall that Chavismo’s confrontation has never primarily been with the United States, but rather with the domestic opposition and economic elites. If Delcy Rodríguez can credibly claim that Venezuela has won US support and that Washington is no longer backing the opposition, she can present this as a strategic victory. She does not need to deny that Maduro’s capture was problematic; she only needs to frame it as having defeated the opposition on that front.

Under those conditions, the discourse of confrontation would be preserved and would continue to be embedded in Venezuelan institutions. The real difficulty would arise if the US were to change course and demand power-sharing with the opposition. That scenario would be deeply problematic for Chavismo. While it might still be manageable, it would be extraordinarily difficult to justify to supporters. It would be just as challenging for Delcy Rodríguez as for María Corina Machado to explain why they should cooperate, why they should sit at the same table. Such a shift would require a profound rewriting of the moral narrative and the institutional grammar that accompanies it, because any genuine power-sharing arrangement would have to extend into the institutions themselves. That would represent a fundamentally different political game from the one Chavismo has played over the past quarter century.

The Difference Between Chávez and Maduro Is Abundance, Not Personality

From a populism studies perspective; to what extent did Chavismo succeed in transforming a charismatic, plebiscitary project into a post-charismatic regime—one in which moral legitimacy, clientelism, and coercion became routinized within the state itself?

Professor Francisco Rodríguez: That’s a great question. It is tempting to focus on the contrasting personalities of Chávez and Maduro, but I would place much greater emphasis on material and economic constraints. Chávez governed during an era of abundance. When he came to power, Venezuelan oil was selling for about $9 a barrel; by the time he died, it was selling for more than $100.

Those rents later collapsed for two main reasons. The first was the sharp decline in oil prices between 2014 and 2016. The second was the political crisis triggered by that collapse, which led, among other things, to US economic sanctions. This raises an unavoidable counterfactual question—one that is necessarily subjective: how would Chávez have reacted to the complete erosion of rents? Would he have behaved differently from Maduro? My view is that he probably would not have.

Had Chávez found himself unable to win elections and facing both a hostile domestic opposition and a US government effectively seeking his removal, I believe he would have become just as repressive as Maduro. There is little in Chávez’s governing style to suggest otherwise. We need only recall the period leading up to the 2004 recall referendum, when Chávez used the Maisanta list to regulate access to public employment in a highly clientelist manner—shoring up support before the vote and intimidating not so much committed opposition voters as potentially neutral citizens and public employees who might have contemplated opposing him. In that sense, similar dynamics would likely have prevailed under Chávez.

That said, as an economist, I am not best equipped—nor is my discipline particularly well suited—to analyze questions of popular or leader charisma. What I can say is that Chávez’s association with a period of prosperity, driven by oil rents and reflected in improvements in living conditions and social indicators through expansive social spending, would likely have made the ensuing crisis resemble Cuba’s “Special Period.” The enduring memory of better times, and of restored dignity and living standards for many of the poor, might have been sufficient to sustain Chávez’s support—something Maduro has been unable to claim.

Chavismo Was Surprised by the Scale of Its Own Electoral Defeat

This contrast is still evident in public opinion today: Chávez remains widely popular, while Maduro does not. As a result, Maduro has relied far more heavily on coercion and institutional control, a tendency that reached an extreme in the 2024 elections, when the government concluded that it had no option but to brazenly steal the vote. Ironically, the fact that Maduro resorted to fraud suggests that he believed victory was still possible. This episode marked a moment when Chavismo was genuinely surprised by the depth of its loss of popular support.

It is important to stress, however, that this surprise did not stem from ignorance of opinion polls or a failure to monitor public sentiment. Careful readings of polling data suggested the election would be relatively close. Nor was it due to an inability to track electoral performance in real time; the government possesses a fairly robust system for doing so, which led it to believe it had mobilized roughly five million votes—enough to make the contest tight even under the opposition’s most favorable assumptions.

What Chavismo was not prepared for was the possibility that, of those five million mobilized voters, around one million would ultimately vote not for Maduro but for Edmundo González. In that moment, the very structures the regime had built revealed their limits. Returning to your question, this suggests that mechanisms of coercion were not fully routinized. They had been routinized for a long period during which they functioned effectively, as evidenced in 2021, when the opposition participated in elections, European Union observers were present, and the government swept the regional contests. At that time, the clientelist model worked.

By 2024, however, something had shifted. That structural break is precisely what the model—one that had kept Maduro in power for twelve years—is now struggling to confront.

CLAPs, Causality, and the Mechanics of Populist Rule

Given that Chávez-era distributive systems continue to function after Maduro’s removal, how should we reassess social policy not merely as welfare provision but as a populist technology of rule—and what does your work on targeted benefits tell us about how redistribution becomes a mechanism of political loyalty under authoritarian populism?

Professor Francisco Rodríguez: I think it is important for me to explain briefly what my work does and what it does not do. This relates, in part, to the broader conversation between economics and the social sciences and to what economists typically try to accomplish. We generally aim to identify causal effects. In my World Development paper on how clientelism works, I use a natural experiment—the repetition of elections in the Venezuelan state of Barinas—to evaluate how social transfers respond to elections. More specifically, I examine the effect of electoral competitiveness on social transfers.

To do so, I use the government’s food package distribution system—the Local Committees for Supply and Production (CLAPs). What I find is quite interesting. When this natural experiment is used to identify causal effects, the results show that, as a consequence of the election, social benefits were targeted more toward median voters—those located in the middle of the political spectrum. This has important implications for the standard narrative on populism. Much of the literature assumes that government supporters are more likely to receive social benefits. That is true as a correlation, as a descriptive statistic, and that point is undeniable. But descriptive statistics are not the same as causal effects. This pattern may exist because the government is actively targeting its followers, but it may also exist because supporters are more likely to self-select into these programs.

It is easy to find anecdotal evidence of opposition supporters saying, “I’m not going to take a food package from the government; I’m not going to give them my information, because that allows them to control me. I don’t like that food; I think it’s poor-quality or even dangerous.” This behavior must be disentangled from other causal factors, such as income differences. Pro-opposition supporters tend to have higher incomes and can therefore more easily opt out of these programs. That disentangling is precisely what the causal experiment helps to achieve.

Between Welfare and Control

So, it is one thing to say that the government uses these programs electorally to target median voters, which is what my paper demonstrates. But it is also important to recognize that, descriptively, government supporters still tend to be the main beneficiaries of these programs. Another key finding in the data is that when people are asked, “Why are you getting CLAP boxes?” or “Why are you not getting CLAP boxes?”, the overwhelming majority respond, “I’m getting them because I registered,” or “I’m not getting them because I didn’t register.” Very few respondents—less than 10 percent—say, “I’m getting them because I support the government,” or “because I have friends in the government,” or “I’m not getting them because I’m not on the government’s side.”

This means that the system is politically targeted, but not necessarily in the way it is often assumed. As a result, voters’ reactions to it are also quite different from what is commonly presumed. In many respects, it appears as the state doing what it is expected to do: delivering food to people and to families. In another paper that I am about to publish in a collection with the Inter-American Development Bank, we estimate the calorie effect of the CLAP program and find it to be substantial—around 500 calories per person. In the context of a massive economic collapse, that can make the difference between famine and the avoidance of famine.

What we are seeing, then, diverges in important ways from standard assumptions. There are, of course, other mechanisms of control. The Carnet de la Patria, for example, operates much more in the classic quid pro quo clientelist manner: if you support me, you receive a monetary transfer. The government uses cash in this way, and it is often considered legitimate for it to do so. As Maduro once explicitly stated during a campaign speech, “This is dando y dando—you give, I give.” He was referring not to CLAP boxes, but to cash transfer programs.

How Everyday Welfare Became a Source of Regime Resilience

At the same time, there is another set of programs that is essentially universalistic. Even if these programs can be politically targeted for strategic reasons, they are universalistic in the sense that everyone is presumed to have access to them, and in practice, those who want access can obtain it. This closely resembles how the Misiones functioned under Chávez, or programs such as Misión Mercal. No one was asked for a government ID card or a Socialist Party card to buy subsidized food at Mercal supermarkets. You simply went in. Yet when you entered the store, saw the staff, and examined the packaging, it was clear that there was political messaging. The implicit message was that the government was doing good things for you. In this sense, it is comparable to Donald Trump signing COVID relief checks and sending them out as personal checks.

My view, then, is that when we try to understand why Chavismo’s popularity—and even Maduro’s support—has remained at around 30 percent, which appears to be roughly what he obtained in the election, we need to ask why, in the context of such a severe economic crisis, it did not fall to 10 percent. In Peru, for example, presidents often have single-digit approval ratings. Why did this not happen in Venezuela? Why was the revolution, in that sense, so resilient? The answer lies in its continued ability to build sources of legitimation, largely by conveying the idea that the state is being administered for you and on your behalf. Even amid economic crisis, the message remains: we are doing our job; we bring you food; we take care of your family’s needs.

When the Model Didn’t Change—but the Conditions Did

The persistence of Chavista governance raises questions about personalism. In retrospect, where do you see the key discontinuities between Chávez and Maduro—particularly regarding elite cohesion, coercive capacity, and the role of elections as rituals of legitimation rather than mechanisms of accountability?

Professor Francisco Rodríguez: Here again, I would return to the counterfactual I mentioned earlier: how different is what we are seeing now from what we might have seen under Chávez had he faced an economic crisis similar to the one Maduro confronted? My view is that the differences are not as pronounced as they are often assumed to be. I do not see major discontinuities in the political model itself, or even in the modes of governance. Many of the apparent discontinuities are better explained by external factors—most notably the collapse of oil revenues and the imposition of economic sanctions, both of which emerged from a particular evolution of the political conflict. That evolution did not stem from the imposition of a fundamentally different governing model, but rather from a deeper issue: the absence of compromise as a viable option within the political culture.

If there is a moment that can be identified as truly decisive—and again, this is not because Maduro is fundamentally different from Chávez—it is the opposition’s victory of a supermajority in the 2015 parliamentary elections, a result that Chavismo initially accepted. The government did not annul or steal the elections and formally recognized the outcome. It did, however, challenge the election of several legislators from the state of Amazonas, a move that ultimately deprived the opposition of its supermajority. That supermajority would have enabled the opposition to initiate proceedings against the Supreme Court or convene a constituent assembly. In that sense, it was a kind of nuclear option, and Chavismo neutralized it by invalidating those legislative seats, while still allowing the opposition to retain a simple majority.

In almost any political system, one would then expect negotiations over cohabitation to follow. Typically, a government in that position would approach the legislature and say, “Let’s work this out. Let’s find a way to govern together. What do you want, and what do we want?” But no such effort was made—by either side. There are, after all, different ways of operating within a political system. One is through negotiation; another is through economic incentives or coercion, which governments routinely employ. Minority parties are bought off; opposition blocs are peeled apart. The government controls the state apparatus and oil rents and can easily approach opposition legislators individually or target small centrist parties, offering ministerial posts or control over specific policy areas—housing, the environment, minority rights. These are standard political tools.

Moral Antagonism and the Breakdown of Political Compromise

In this case, the government had two basic options. It could have sat down with the opposition coalition to negotiate a coexistence arrangement that would allow governance and the passage of legislation. Alternatively, it could have pursued a piecemeal strategy, fragmenting the opposition to construct a working majority. Maduro did neither, and the opposition likewise refused to engage in such processes.

This is where I would locate the core problem. I would hesitate to call it a discontinuity in the political model itself, but it was certainly a discontinuity in outcomes. The system was simply not designed to operate under a constitutional arrangement that required cohabitation. And this is not unique to Chavismo. It reflects a deeper feature of Venezuelan political history. During the democratic period that began in 1958, parliamentary and presidential elections were held simultaneously, ensuring that presidents almost always governed with a compliant Congress. The lone exception was in 1993, when Rafael Caldera won the presidency with only a plurality, leaving his party without congressional control and forcing some form of accommodation.

The belief that governments do not need to negotiate with the opposition is deeply ingrained in Venezuelan political culture. That is where the system—on both sides—ultimately breaks down. And it breaks down, once again, because of the politics of moral antagonism we discussed earlier. How can you justify governing alongside an actor you have portrayed as an existential enemy, as the embodiment of unpatriotic or immoral behavior? You cannot. Neither side could.

This dynamic was evident on the opposition side as well. When Henry Ramos Allup assumed the presidency of the National Assembly, he announced that the opposition would seek a constitutional route to remove Maduro from office within six months. In effect, he was openly advocating regime change. Both sides were locked into this confrontational mode, and their inability to move beyond it precipitated the escalation of the political conflict—ultimately leading to the adoption of scorched-earth strategies that inflicted severe damage on the economy.

From Democratic Opposition to Zero-Sum Politics

And finally, Professor Rodríguez, drawing on your New York Times analysis of Machado’s hardliner identity—including the symbolic handing over of her Nobel Peace Prize medal to President Trump—what does this episode reveal about the risks of moral absolutism, charismatic personalization, and alignment with coercive external power in populist contexts? More broadly, what does the Venezuelan case tell us about Trump’s transactional approach to authoritarian regimes and the dangers it poses for democratic oppositions elsewhere?

Professor Francisco Rodríguez: It is a very revealing episode because it encapsulates a central dilemma in opposition politics. Moderates within the opposition struggle to mobilize voters around their projects and are highly vulnerable to being denounced as collaborationists or as having been co-opted by the government. As a result, moderate opposition figures tend to reach a political dead end. Once they attempt to articulate an alternative based on compromise, they quickly lose momentum.

Returning to my earlier point about confrontation as part of the modus vivendi, the issue is not that no one has questioned this logic. Rather, within the opposition, those who have challenged it have not been electorally successful. This is evident in the case of Henri Falcón, who failed as a candidate in 2018 despite Maduro being as unpopular then as he was in 2024, according to opinion surveys. The same dynamic is visible with Henrique Capriles, who was once a highly popular opposition leader but lost significant support after adopting a more moderate stance. It is also evident in the case of Manuel Rosales, the governor of Zulia, who emerged as a plausible replacement after Machado was disqualified. Rosales had credibility as someone who had reclaimed Zulia from Chavismo and governed from the opposition without framing politics as a zero-sum struggle. Yet he was ultimately sidelined, largely because Machado’s supporters undermined him on the grounds that they reject any form of collaboration.

It is also important to recall that Machado herself was a vocal critic of Juan Guaidó, whom she regarded as too conciliatory toward Maduro. Her main criticism was that, as president of the 2015 National Assembly and interim president, he failed to invoke constitutional powers to formally call for foreign military intervention—effectively inviting external troops into the country. She criticized him forcefully for this. Looking further back, Machado was present at the swearing-in of Pedro Carmona as de facto president following the 2002 coup against Chávez. This is not mentioned simply to question her democratic credentials—though it is often raised in that context—but to underscore the narrative that underpins her political stance: the belief that Chavismo was never democratically legitimate. In her view, Venezuela was already a dictatorship in 2002, and a coup against that dictatorship was therefore justified.

Crisis, Charisma, and the Appeal of No Compromise

This narrative resonates strongly in a country that has experienced the largest economic contraction ever recorded in peacetime, where roughly a quarter of the population has emigrated, poverty rates have exceeded 90 percent, malnutrition—virtually nonexistent in the mid-2010s—has risen to more than 25 percent, and the government has grown increasingly authoritarian. In such conditions, it is understandable that voters are drawn to a leader who argues that Maduro remains in power because previous challengers were not forceful or resolute enough. This is how Machado constructs her political persona: as the uncompromising figure, the leader unwilling to strike a deal with Chavismo, the one who promises not coexistence but defeat. Her slogan, hasta el final—“to the end”—signals a final confrontation in which victory is assured.

This narrative mobilized voters on two levels. Traditional opposition supporters embraced it enthusiastically, given their deep hostility toward Chavismo. At the same time, more centrist voters—some of whom had previously supported Chavismo—were also drawn to her. In many respects, Machado embodied characteristics associated with Chávez himself: a young, decisive, energetic leader offering a dramatic rupture. The promise she made closely resembled the promise Chávez made in 1999. This helps explain why roughly a third of the Venezuelan electorate reports supporting María Corina Machado while simultaneously viewing Chávez as a good president.

That support, however, did not entail a transformation of her underlying narrative or that of her core constituency. Instead, it reinforced a political posture fundamentally incompatible with governing alongside Chavismo. This is where the Trump administration’s intervention becomes especially revealing. The decision was to remove Maduro—to decapitate the regime—without fully dismantling it. Comprehensive regime change would have required military occupation, significant loss of US personnel, and a long-term commitment unlikely to be sustained by public opinion. As Iraq and Afghanistan demonstrated, the costs of occupation often exceed those of initial military victory.

Instead, the United States adopted an approach reminiscent of earlier interventions, such as in Cuba and the Philippines after the Spanish-American War or in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Nicaragua in the early twentieth century. The logic is straightforward: military leverage and conditionality remain in place, while local actors govern. It is more efficient to rule through domestic elites who follow US directives than to administer the country directly.

Why Machado Didn’t Fit the New Power Strategy

This framework also helps explain how Trump has framed his relationship with Machado. The implicit message is that she is admirable—even symbolic, as evidenced by the Nobel Peace Prize medal—but politically impractical. Incorporating her into governance would disrupt the broader strategy. After Maduro’s removal, Venezuela ceased to be primarily about Venezuela; it became a demonstration of power. The operation showcased the US capacity to remove a foreign leader with extraordinary efficiency, without the loss of American lives, and to detain him in the United States. Many observers, myself included, believe this likely involved internal collaboration, making it resemble a palace coup under the cover of military intervention. For Trump, however, the narrative is unambiguous: this is what American power looks like.

This is where Trump’s arrangement with Delcy Rodríguez acquires broader significance. The message is simple: compliance is rewarded. Speaking recently in Davos, Trump claimed—characteristically exaggerating—that Venezuela would earn more in the next six months than it had in the previous twenty years. That assertion is plainly false, given that those twenty years include the Chávez-era oil boom. But the rhetoric is less important than the underlying signal: the new Venezuelan authorities are doing what Washington demands, and they are being rewarded for it.

Trump delivered this message before an audience of European leaders, implicitly asking them which path they wished to follow—whether in relation to Venezuela, Greenland, or other geopolitical issues. Cooperation would bring benefits; resistance would invite hostility. This logic extends beyond Europe to the Middle East, including Gaza, and to Latin America more broadly. It reflects an effort to reassert US dominance in what Trump conceives as the Western Hemisphere, consistent with a revived Monroe Doctrine logic.

What emerges from this approach is an attempt to construct a functional protectorate—economically, and perhaps politically. Yet a protectorate, by definition, lacks full sovereignty. Under such conditions, the meaning of democracy becomes ambiguous. The likely outcome is an authoritarian system, potentially evolving into a form of competitive authoritarianism. Even if Venezuelan oil revenues were to increase by only a fraction of Trump’s exaggerated claims, the resulting economic growth—on the order of 20 to 25 percent annually for several years—would make such a regime politically viable.

Just as Maduro’s popularity collapsed with the economy, Delcy Rodríguez could gain substantial legitimacy if she presided over sustained economic expansion. That is the bargain Trump is offering—not out of benevolence, but because he wants Venezuela to serve as a showcase: a revitalized economy demonstrating the rewards of alignment with US hegemony. Ultimately, that is the message Trump seeks to send to democratic oppositions and authoritarian regimes alike: these are the new rules, and this is what you get when you play along.