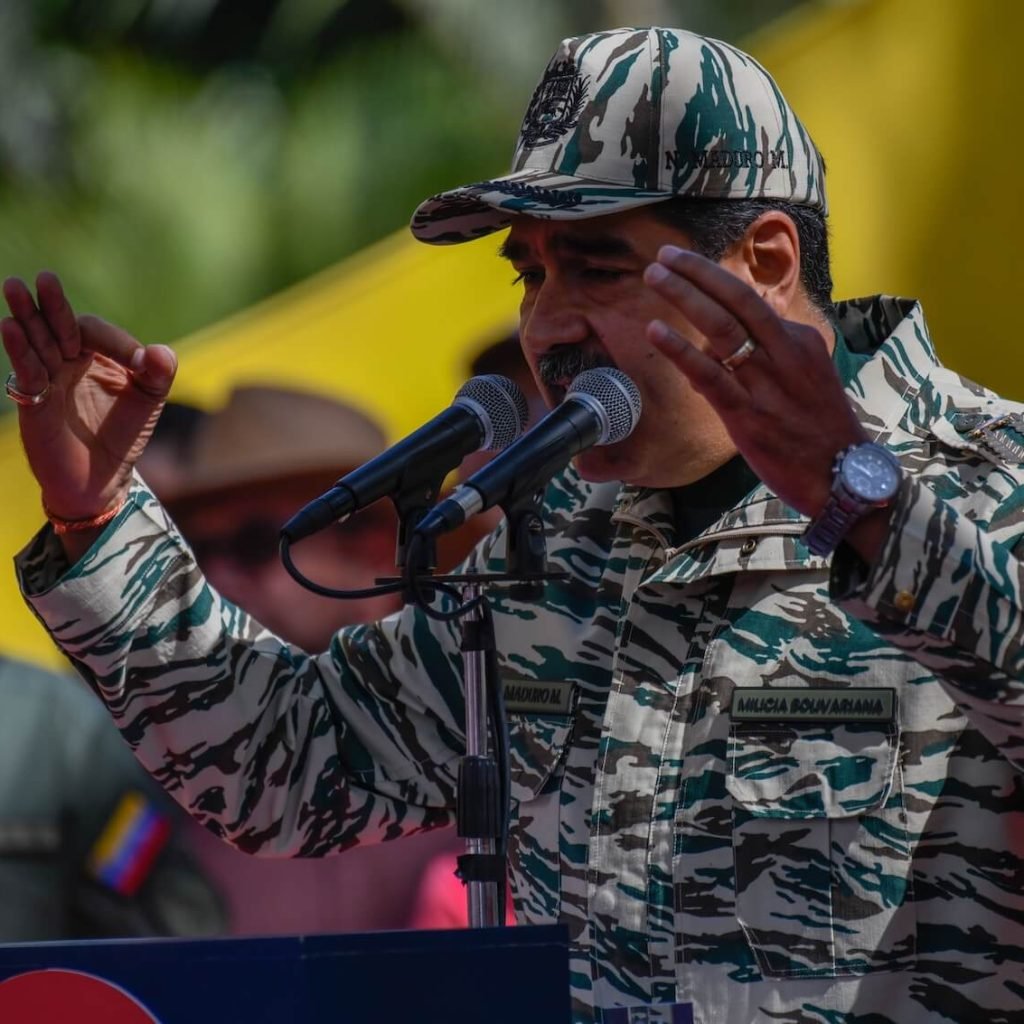

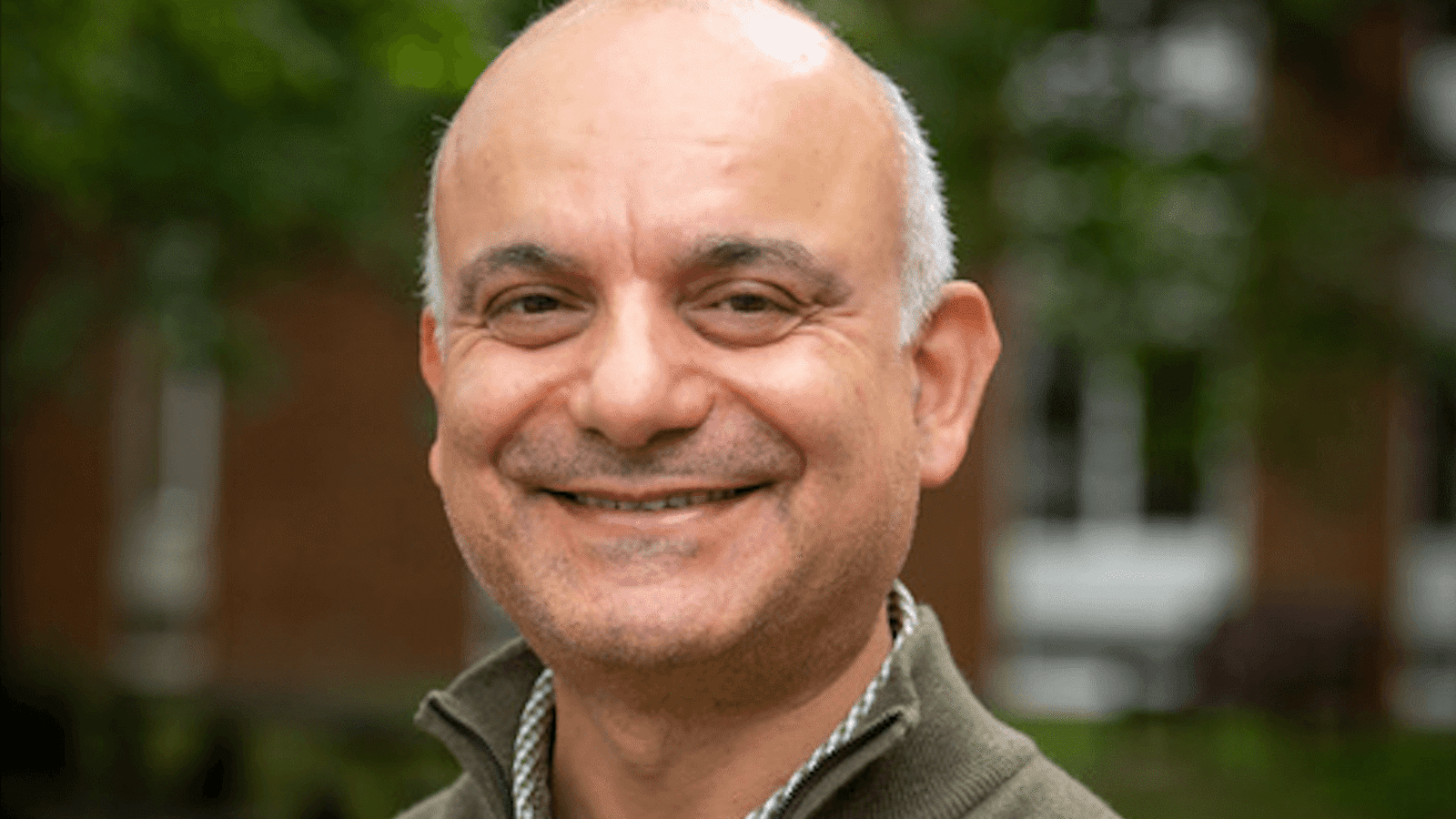

Professor Benjamin Carter Hett, a leading historian of Nazi Germany at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY, joins ECPS to reflect on the promises—and pitfalls—of historical analogy in an age of democratic stress. Grounded in his research on Weimar collapse and authoritarian mobilization, Professor Hett argues that humiliation remains a key driver of populist politics, pointing to Trump’s insistence, “I am your retribution,” as a revealing signal of grievance politics. He also draws sharp structural parallels between Nazi attacks on “the system” and contemporary slogans such as “the swamp,” which work to delegitimize democracy from within. Yet Professor Hett resists false equivalence: Trump, he emphasizes, is “vastly less astute and vastly less ruthless than Hitler,” and lacks “any compelling ideological vision,” remaining “totally improvisatory.” The interview probes elite accommodation, “reality deficits,” and backlash dynamics.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In an era increasingly shaped by populist insurgencies, democratic erosion, and polarized historical analogies, few scholars are better positioned to assess the uses—and abuses—of the past than Professor Benjamin Carter Hett. A leading historian of Nazi Germany at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY, Professor Hett has devoted his career to analyzing how democratic systems collapse from within. In this wide-ranging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), he reflects on the dynamics of authoritarian mobilization, the politics of grievance, and the limits of historical comparison—culminating in his striking assessment that “Trump is, of course, vastly less astute and vastly less ruthless than Hitler.”

Professor Hett’s analysis begins not with institutions but with emotions. Drawing on his research into the Nazi rise to power, he argues that humiliation—rather than ideology alone—often supplies the combustible fuel of authoritarian movements. A “core explanation” for Nazism’s ascent, he explains, was a widespread perception among supporters that they had been “humiliated by domestic elites” and by the settlement of World War I. He sees echoes of this dynamic today: “Substantial segments of the electorate in the United States and in European countries appear to be experiencing a sense of humiliation reminiscent of that felt by many Germans in the interwar period.” Trump’s campaign rhetoric, especially the promise “I am your retribution,” exemplifies how perceived loss of status can be politically weaponized.

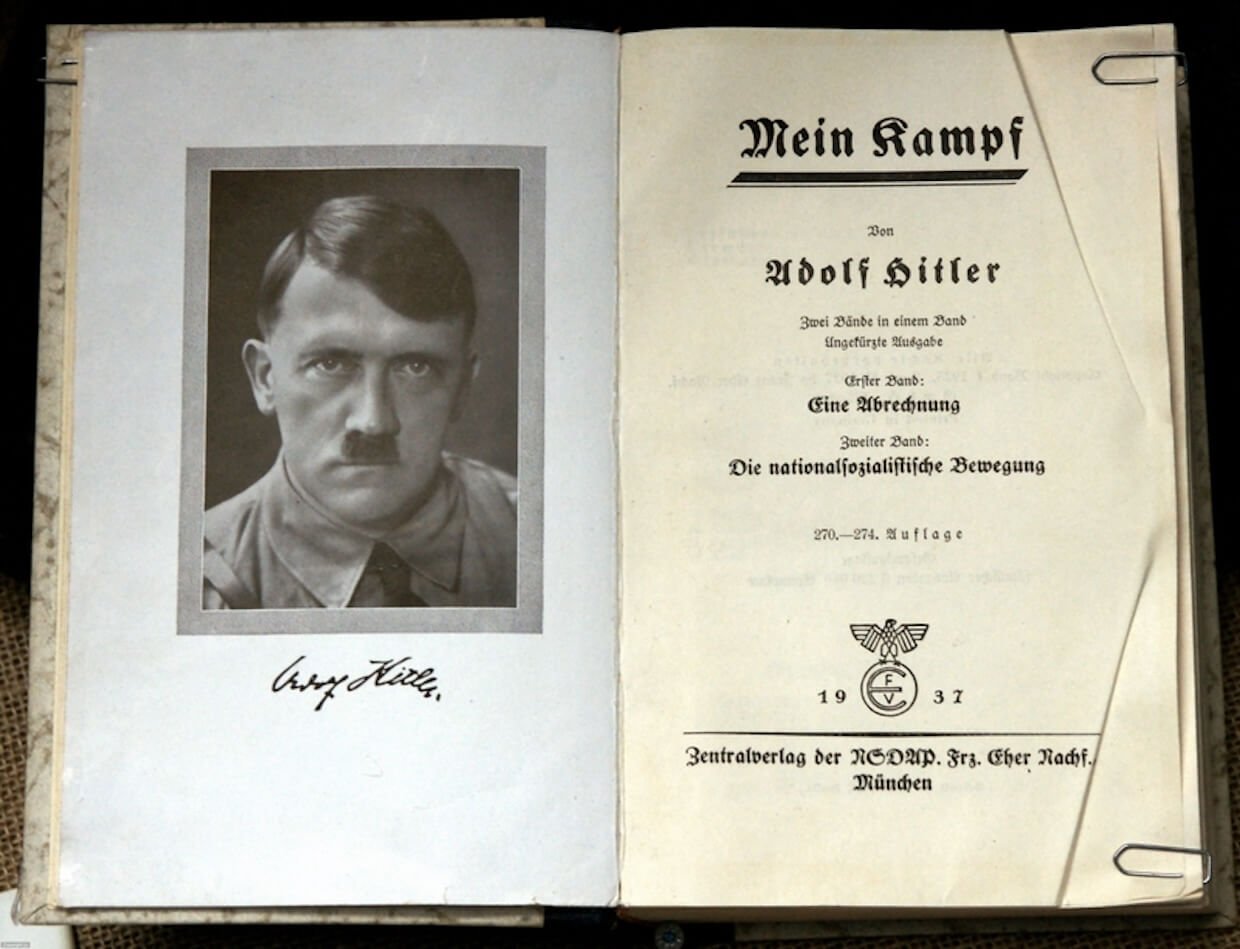

Yet the interview’s central theme—highlighted by its title—is not crude equivalence but analytical differentiation. Professor Hett repeatedly underscores that, despite structural parallels, Trump lacks the strategic capacity and ideological coherence that made Hitler historically transformative. Whereas Nazism fused charismatic authority with a totalizing worldview—what Nazis called “the Idea”—Trumpism appears improvisational, transactional, and deeply personalist. This distinction, Professor Hett suggests, limits its authoritarian potential. Trump, he argues, possesses “no compelling ideological vision behind him” and is “totally improvisatory,” driven more by a desire for adulation and material reward than by a programmatic project of domination.

The interview also revisits Professor Hett’s influential argument that democratic breakdown can stem from “hollow victory” as well as defeat. Despite America’s triumph in the Cold War, many citizens experienced globalization, automation, and rising inequality as loss rather than success, producing resentment analogous to the disillusionment that followed World War I. Such grievances, once reframed as cultural humiliation rather than economic hardship, become fertile ground for populist mobilization.

Equally significant is Professor Hett’s discussion of elite miscalculation. Just as conservative elites in Weimar believed they could harness Hitler’s popularity, many contemporary political and economic actors initially treated Trump as a manageable aberration. History, he warns, shows how such bargains can backfire—even when the leader in question is less capable than his predecessors.

Ultimately, Professor Hett’s cautiously optimistic conclusion is that the very differences highlighted in the title—Trump’s relative lack of ruthlessness, ideological depth, and strategic discipline—may also constitute democracy’s resilience. Historical patterns may rhyme, he suggests, but they do not mechanically repeat.

Here is the edited version of our interview with Professor Benjamin Carter Hett, revised slightly to improve clarity and flow.

Humiliation as the Hidden Engine of Authoritarian Politics

Professor Benjamin Carter Hett, thank you so much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: In “The Power of Grievance,” you frame humiliation as the animating force behind authoritarian mobilization. How does this concept refine—or challenge—more institutional explanations of democratic breakdown in The Death of Democracy, particularly in the US case where institutions remain formally intact?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: Let me begin by saying that I am primarily a historian and a scholar of 20th-century Germany, particularly of the rise of the Nazis. From extensive research on the Nazis’ ascent in Germany during the 1920s and 1930s—I’ve written three books on the subject, among other works—I came to the conclusion that a core explanation for their rise was a widespread sense of humiliation among their constituency: humiliation at the hands of domestic elites, humiliation imposed by the victorious Allies of World War I, and so on.

Given what I do for a living, and the times we are living in, I am often asked about parallels between that historical episode and contemporary developments. The more I examined current events and read widely on American and European politics today, the more I felt that the explanation for much of what is happening now is broadly similar. Substantial segments of the electorate in the United States and in European countries appear to be experiencing a sense of humiliation reminiscent of that felt by many Germans in the interwar period.

As for how this perspective modifies the outlook: there are, of course, countless possible explanations for the rise of authoritarianism. Some are economic-structural, others political, social-psychological, or cultural—suggesting that certain societies may be predisposed to particular forms of authoritarian politics. Nothing in scholarship is ever absolute, and elements of all these factors are likely present in any given case where authoritarianism gains electoral traction.

But, for what it is worth, I am persuaded that if you return to what politicians are actually saying to people—and examine the resulting voting behavior in context—you repeatedly encounter the theme of humiliation. There are many examples we could discuss, but one is particularly telling: the fact that Trump campaigned so heavily on the claim, “I am your retribution.” What do his voters need retribution for? It suggests that they feel they have experienced a significant degree of humiliation in recent years or decades. I think there are many other such examples, but that one captures the point quite clearly.

From ‘The System’ to ‘The Swamp’: Recycling Anti-Democratic Rhetoric

You show how Nazi contempt for “the system” delegitimized Weimar democracy from within. To what extent do contemporary slogans such as “the swamp” or “deep state” perform a structurally similar function in Trumpism, even without an explicitly revolutionary ideology?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: That’s a great point, and you’re quite right, too, about the lack of an explicitly revolutionary ideology. But when Trump talks about draining the swamp and campaigns on that, it is doing exactly—indeed 100% of what Nazi rhetoric in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s did.

Just to give you an example, the Nazis always talked about “the system,” a kind of capital-S System. “The System” was their code word for Weimar democracy, which they worked very hard to paint as corrupt and weak, in very much the sort of Trump-like “swamp” rhetoric they used. Nazi propaganda would, for instance, always highlight what they saw as corruption by the democratic parties, especially by the Social Democrats, the dominant democratic party at that time. They would emphasize corruption, weakness, dysfunction, and the incompetence of democracy, always using corruption as a wedge to say: look how this system is paying off fat cats and criminals; look how this system stands behind war profiteers and gangsters. This is a fundamentally illegitimate system; therefore, you should turn to us, because we represent, in their words, cleanliness and decency.

And Trump makes exactly the same argument. Despite the—to put it mildly—rather glaring corruption of his administration, which probably even outdoes the Nazis in corruption (and the Nazis were plenty corrupt), the rhetoric is just that: rhetoric that conceals, in both cases, a much more profound kind of corruption.

Why Cold War Triumph Did Not Prevent Democratic Discontent

You emphasize that authoritarian grievance can emerge not only from defeat but also from “hollow victory.” How analytically useful is this idea for understanding American populism, given that the US emerged as the undisputed Cold War victor?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: One thing I think is a bit of a puzzle is why the United States could have achieved, in a sense, a kind of unmitigated triumph at the end of the Cold War, and yet have pretty quickly, in historical time after the end of the Cold War, fallen prey to a movement like Trump’s—a demagogic campaign of resentment that seems to speak to people who feel they are losing from the system. So, for a historian like me, the question arises: this actually looks rather like the 1920s, an increasingly dark time that followed a seemingly spectacular democratic triumph. So, what is it about that?

If you look a little more closely, you find that, for many Americans, the end of the Cold War did not deliver anything that looked like a victory. This is largely due to economic orthodoxy and, to some extent, technological change, which have taken hold since the end of the Cold War. The two things combined—the move to greater globalization, which for many Americans meant offshoring jobs and/or losing domestic jobs in competition with foreign manufacturers—and, coupled with that, technological change, including increasing automation of the workplace. God only knows what AI is going to do to all of us, but there has been a narrative of technological change replacing jobs for some decades now.

What this has done is essentially deprive the vast majority of Americans of real economic gains over a period of the last 50 years. I think it has become acute since the 1990s, but it has been going on since the 1970s. There is quite clear data on this, and it is breathtaking that, for 99% of Americans, there has been no real gain in income or net worth since the 1970s, whereas the top 1% has achieved spectacular gains in income over the same period. And this is a result of politics. It is not anything inevitable in the economic order; it is a result of political decisions that have been made. Although many people who vote for Trump do not really know or understand this, they experience its effects, and that creates a kind of justifiable anger.

But the subtle point—and this is one of the arguments of my piece—is that it then becomes, politically, not exactly a literal economic grievance, because it gets transmuted into something else. What people receive is the message: my country, my society, does not care about me. My society does not pay attention to me; it neglects my interests. There is an elite interest that is taking precedence. That mood has increasingly taken hold in America since the 1990s, at a time when we should have been basking in democratic triumph, but it has not worked that way.

Much as—and here there is a very close parallel again—at the end of World War I, similar things happened. Following a democratic victory, various kinds of economic crises beset the Western democracies. To give an illustrative quote, I remember reading something a British veteran of World War I said, I think sometime in the 1920s: “We were promised homes for heroes at the end of World War I.” This was an election promise by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George in 1918, when he proposed a massive housing program for returning veterans. “So, we were promised homes for heroes. Well, actually, it took a hero to live in it. I would never fight for my country again.” That speaks exactly to the kind of anger—what I call a hollow victory—that Americans have experienced in large numbers since the end of the Cold War.

Hostility to Globalization, Alliance with Wealth

Your work highlights how fascist movements selectively appropriated anti-capitalist and socialist rhetoric. How should scholars interpret Trumpism’s simultaneous hostility to globalization and embrace of oligarchic capitalism without collapsing the analogy into false equivalence?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: In the historical case of fascism in the 1920s and 1930s, the scholar who has put this most clearly and effectively is the great Robert Paxton, who has a terrific book called The Anatomy of Fascism. What Professor Paxton says, quite astutely, is that fascist movements historically moved into the political space where there was room for them, making whatever alliances worked to move them forward at that moment. In the earlier days—you see this with Mussolini in the very early phase of Italian fascism, and with Hitler a few years later—the available space was one of resentment, especially among working- or lower-middle-class people, about the nature of the economic order, with many feeling they were being shafted by a certain kind of capitalism.

So, the Nazis rhetorically moved into that space and positioned themselves as anti-capitalists, some more sincerely than others. There were, weirdly enough—you may have heard the term—we sometimes speak of “left-wing Nazis,” those who took anti-capitalism and anti-elitism more seriously. Hitler was not one of those people; he was what we call a right-wing Nazi. But he was willing to let the left-wing Nazis rhetorically have some leash, as it was politically useful. And then, of course, famously later, he had them all murdered in 1934, which shows what he really thought of that.

Trump is doing something similar without quite realizing it. What is interesting about Trump is that he is so extraordinarily stupid and tactically inept that he does these things on a very obvious level. He is tactically astute enough, usually, to figure out what he can say that will be electorally successful, but he is in no way a strategic thinker capable of putting it into any coherent package. So, with Trump you get, day by day, whatever has just passed through his mind. Especially when he was campaigning, particularly in 2016, you heard not only anti-globalization but quite directly anti-capitalist rhetoric from him.

But, of course Trump is also extremely corrupt, so once in power he wants to find ways for people to give him money. In practice, he cozies up to tech moguls and others; for example, Jeff Bezos giving $40 million for that awful movie about Melania, or Trump receiving a $400 million jet from Qatar. It is sort of mind-blowing.

Trump is both so corrupt and so devoid of tactical sense—and, I guess, of any sense of tact or taste—that he simply does all these things out in the open. So, you see it extremely clearly with Trump. You can see similar patterns with Hitler and Mussolini, though they were astute enough to slightly conceal the extent of their hypocrisy about anti-capitalism. With Trump, what you see is what you get, and what you get is what you see. It is all out there. But the basic tactical and rhetorical pattern is very much the same.

The Illusion of Control: When Elites Enable Authoritarianism

In Weimar Germany, conservative elites believed they could control Hitler. Do you see comparable patterns among US political, judicial, or economic elites who initially treated Trump as a manageable aberration rather than a systemic threat?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: Yes, very much. Perhaps a bit less now than some years ago. This was particularly an issue in Trump’s first term in office. Back then, I wrote a book called The Death of Democracy, which is actually an account of the Nazis’ rise to power. One of the main themes in that book is that there was a sort of Faustian bargain between what you might call the establishment elites in Weimar Germany—particularly business elites and military elites—who did not like Hitler, did not like his party, and did not respect it, but couldn’t help noticing that Hitler got votes. Especially by 1932, he was getting about a third of the votes, and his party was by far the biggest in terms of electoral support. So, these elites were astute enough to think this was maybe something they could use.

They could make a deal with him, arrange for his electoral constituency to come in behind them, and that would advance their agenda—an agenda of deregulation and anti-union approaches for business, and an agenda of an arms buildup for the armed forces. Notoriously—probably no one needs me to tell them this—that deal didn’t work out very well, because many of these elite gentlemen profoundly underestimated Hitler. They underestimated his cunning and his ruthlessness. It took arguably not much more than about four weeks for them to be captured by him in power and then pushed aside from all influence.

When I wrote my book—it came out in 2018—although I never mention Trump or current politics anywhere in it, there is meant to be a rather loud subtext, and I’m pretty sure no one who has read the book has missed it. It is about parallels, and the parallel I thought was strongest and most telling was exactly this kind of elite accommodation of a dangerous and potentially authoritarian political movement that they believed would advance their own agenda and that they could control. I had a feeling the same thing would happen—that Trump would overwhelm them. Trump is, of course, vastly less astute and vastly less ruthless than Hitler. But much of the same thing has, in fact, happened. He has basically destroyed the Republican Party as an actual conservative party. There are virtually no moderate Republicans left anymore, certainly at the congressional level.

It has become very much his party, because those elites, in fact, failed to control him. They have failed to control him even more, certainly in his second term. He has done things that most elites don’t want, like tariffs and many other policies. No one is happy about his threats to Greenland; no conventional conservative is happy about his downgrading of America’s alliances or trade interests, but they simply can’t control him anymore.

I do think at least they are starting to become aware of it. There is less self-delusion among American elites now about what Trump is. It’s kind of too late. If we are going to stop this guy from doing more damage, it is not going to be the business elites who do it. We’ve seen in Minneapolis who is going to do it, but that is another question.

From the Big Lie to Algorithmic Disinformation

You describe the Weimar Republic as suffering from a fatal “reality deficit.” How does this concept translate into an era of algorithmic misinformation, partisan epistemologies, and the collapse of shared factual baselines?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: It’s a great question. One of the things that I say a lot—and I don’t know if anyone ever agrees with me, and it’s fine if no one does—but as a historian, I tend to think there is actually never anything really new. The environment we live in of social media– and internet-driven disinformation is not incredibly new. You don’t need the internet for that. As Exhibit A for my contention, I would point to the Weimar Republic, which had a very vigorous media environment.

You see different figures, and it depends how you count them, but there were something like 40 or 50 daily papers in Berlin in the 1920s, covering the whole political spectrum—from communist to Nazi and everything in between. There was also pioneering radio, films—there were many ways for information to circulate. Posters were a very big deal. In my book The Death of Democracy, I discuss how the Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels placed enormous emphasis on posters, saying, “Our election campaign is going to be all about posters.” So, there were all these ways to disseminate information.

And just because something appears in a newspaper does not mean it is not disinformation, and there was plenty of that in Weimar. A prime example is what was called, even then, the Big Lie: the idea that Germany did not really lose World War I—that Germany was on the verge of victory when cowardly, treasonous politicians, liberals, and socialists betrayed the country by surrendering to the Allies. This narrative originated with military leaders such as Field Marshal Hindenburg and General Ludendorff and was then eagerly adopted by figures like Hitler.

There are striking parallels here to Trump’s narrative about the 2020 election, claiming he did not really lose but was betrayed by a democratic establishment. That narrative has been widely circulated, and many Republicans and people on the American right believe it. It has effectively become a loyalty test: if you are to play any role in Trump’s party or administration, you must affirm that he actually won the 2020 election.

Similarly, perhaps half of Germans in the 1920s and 1930s believed that Germany had been on the verge of winning World War I—which is nonsense to exactly the same extent that it is nonsense to claim Trump won the 2020 election. Germany was, in fact, being militarily crushed when the armistice was signed in 1918.

So that Big Lie spread extremely effectively using the media technologies of the time. If the internet had existed then, it is hard to imagine it being more effective than what already existed in propagating that narrative. There is obviously an advantage today in the speed with which electronic communication spreads, but I do not think it represents a profound, fundamental difference from the past.

I do think America today is also a country suffering from a massive reality deficit, much as Weimar did in the 1920s, and for many of the same reasons: dishonest politicians exploiting the media available to them. In that sense, it is very much the same.

Personalist Power Without a Guiding Doctrine

Hitler combined charismatic authority with a coherent—if grotesque—ideological worldview. Trumpism appears far more improvisational and transactional. Does this weaken the authoritarian analogy, or does it suggest a more flexible and therefore resilient form of personalist rule?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: Probably both, but I’m one of those people who, on these issues, is more of a glass-half-full than a glass-half-empty type. I am, for a number of reasons, fairly optimistic about the longer-term prospects of American democracy. I think we will get through Trump and continue operating as a democracy. One reason for that is exactly your point: It weakens Trump’s ability to be an effective authoritarian that he has no compelling ideological vision behind him. He is, as you put it, exactly right—totally improvisatory.

Part of what made Hitler successful—certainly with his base, his core followers who became the spine of his regime—was his ability to convince them that he was the spokesperson for a powerful idea. The Nazis talked about “the Idea” all the time, a kind of capital-I, the Idea. They internalized it deeply, and that motivated a great deal of their conduct. There is nothing remotely comparable with Trump.

As a matter of fact, the distinguished historian Timothy Snyder wrote a piece sometime last fall that I thought was spot on. He made this point, noting that one of the differences between Trump and Hitler is that Hitler had a sweeping, deeply embedded, fairly all-encompassing ideological worldview. That, in a sense, not only attracted followers but also gave a blueprint for his actions and pushed him toward what he ultimately did.

Trump has nothing remotely like that. Trump basically—among his many attributes is a shockingly profound inferiority complex—just wants to be flattered all the time. He wants to ride around in Air Force One, and he wants people to give him money. It does not go much farther than that. Honestly, for Trump, that is it. Hitler—though I do not think anyone would suggest I am advocating for him—did have a sweeping ideological vision that he worked very hard to fulfill. Trump does not. As I said, Trump wants to ride around on Air Force One, be told he is wonderful, and be given money. Ultimately, that is not something you can really package as a compelling ideology for which people would be willing to die.

Authoritarian Impulses Confront Constitutional Constraints

Drawing on your research into emergency decrees and legal normalization under Nazism, how should we interpret contemporary efforts to weaponize prosecutions, executive orders, or “law-and-order” rhetoric in ostensibly constitutional systems?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: That has definitely been a feature of Trump’s second term. This kind of comes back to what he said about how he would be retribution for his followers. I think what he really means is that he will be retribution for himself. So, we have obviously seen targeted prosecutions of people that Trump feels have insulted him or hurt him in some way.

There is a weak parallel here to Hitler, in the sense that in the famous event of the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, when, as I mentioned earlier, Hitler had a number of people who could be seen as left-wing Nazis murdered, he also, on the same occasion, had murdered a number of people against whom he had some particular kind of grudge, going back in some cases a decade or more. He had been holding these grudges for a while. Trump is like that, except here is where we get to the difference, which is really important.

We still, basically, in America, have a democracy. We still basically have a legal system, although Trump is trying to erode it and is eroding it to an extent, but it is still basically functioning. So, he has to try to prosecute these people through the legal system, and we have seen that it does not work very well, because the legal system basically takes his efforts to corrupt it and spits them out. There have been any number of such cases. He keeps bringing, or getting his Justice Department to bring, charges against people like the former FBI Director Comey or the New York State Attorney General Letitia James. Grand juries that need to approve an indictment will not approve them, or judges will throw them out. Just yesterday, a judge threw out a case against Senator Mark Kelly, who is in a legal battle with the Defense Secretary, Hegseth, for things that he said in a video. Again, the justice system is basically rejecting these efforts. If Trump were more Hitlerian, if he were more ruthless, he would find ways to get these people anyway, but he is not doing that.

The system is, in a sense, holding against his efforts to abuse it. So, I think, so far, so good on that. I mean, what he is doing is horrific. His Attorney General, Pam Bondi, is the most corrupt and probably most incompetent Attorney General the United States has ever had, and she just does whatever he wants her to do. But it is failing. Something we need to keep in mind about Trump is that he does any number of awful things, but most of the awful things he does fail, and they fail because they run up against something in American society that resists them, as in this case with the justice system.

Public Resistance and the Constraints on Authoritarian Consolidation

Weimar politics were marked by overt paramilitary violence, whereas contemporary American politics often operates through a mix of performative menace and state-sanctioned coercion, including the expanded mobilization of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the deployment of the National Guard in ways critics describe as intimidating or terrorizing civilian populations. In your view, how much actual violence—or credible threat of violence exercised through formal state institutions—is necessary for authoritarian consolidation in a mature media democracy?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: The answer is lots. And here again, I’m sort of a glass-half-full guy. Let me say that there is no one in this country who is more angry than I am about ICE, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, basically a police agency, or the somewhat similar organization Customs and Border Patrol, which also has police officers of a sort that have been on the ground, notably in the last month or so in Minneapolis. There is no one who abhors that more than I do or is more angry about the violence, including the murders they have perpetrated, or the myriad abuses of the Constitution—breaking into homes without a warrant, breaking into cars without a warrant. ICE is basically a criminal organization. That said, I am actually working on writing something right now about this.

The parallel to the violence of the historical fascist era basically fails simply on scale alone. The numbers would go something like this—I have just been looking this up. There are right now about 22,000 ICE agents in the United States. We could compare ICE and the kind of violence it creates and its style—being in military-style uniforms, patrolling the streets, marauding, conducting violence rather randomly against people. That all looks quite a bit like what the Nazi stormtroopers, the famous Brownshirts, were doing in 1933 and 1934.

Except that in 1933 and 1934 there were between 3 and 4 million young men in the Brownshirts in a country that at that time had about 66 million people. If you multiplied that out to be proportional to the American population now, you would have somewhere between 16 to 21 million uniformed paramilitary people roaming the streets of the United States. What we have is 22,000. So, we need to keep in mind the actually quite mind-blowing scale of the violence that the Nazi regime in 1933 and 1934 was meting out to its own people through these stormtroopers and through agencies like the secret police, the Gestapo. In comparison to what we have in the United States now, as terrible as the violence in, for instance, Minneapolis and the murders there have been, the scale is minuscule compared to what the Nazis did. I think we need to keep that in mind.

It would probably take Nazi-scale mobilization and violence for the Trump administration to get itself into the league of being a real dictatorship, and that is just not going to happen. The other thing I want to say quickly is that, as a very close student of what happened in Germany in 1933 and 1934, I can say there was nothing remotely like the mobilization of ordinary people in Minneapolis to create networks to push back against ICE. It has been remarkable how we have been reading and seeing about this in the last month or two—the way these spontaneous networks have gotten organized, where people communicate via cell phones or whatever, and as soon as ICE agents go anywhere, people notify that neighborhood, follow and track them, film them, and put videos on social media.

All of this has hindered ICE in doing what it wants to do, but it has also shredded its public reputation. Americans now are overwhelmingly—polls show roughly two-thirds—against what ICE is doing, and as that has happened, it has also shredded Trump’s approval rating, which is now at pretty much record lows for any president. The only competition Trump has right now for a low approval rating among other presidents is himself in his first term. So, the spectacle of what ICE is doing is really not selling with Americans, and they are pushing back commendably, in ways that one did not see in Germany in 1933 and 1934. All of those differences are quite important.

Can Democratic Pushback Contain Authoritarian Populism?

Drawing on your work on Weimar Germany and the dynamics of authoritarian mobilization, how resilient do you judge Trumpism and a Trump-led administration to be in the face of potential democratizing backlash—whether through electoral defeat, judicial resistance, elite defection, or mass civic mobilization? More specifically, do historical analogies suggest that such backlash tends to constrain authoritarian projects, or can it paradoxically strengthen them by reinforcing grievance narratives and siege mentalities?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: That’s an interesting question. As I said before, I am fairly optimistic that we’re going to get through Trump. And in 2028, we’ll have a better president, and we’ll be more or less okay as a country. I don’t want to minimize the people who are really suffering the brunt of this, especially people in immigrant communities or communities of color. There is damage being done to people that is not fixable, but American democracy is going to get through this.

I have also said, pretty much since the beginning of this second Trump term, that although I cannot quite foresee the shape it will take, I do not think we’re going to get through this without a crisis of some kind. The crisis would take the form of Trump doing something—whether it is ordering soldiers onto the streets of American cities, resulting in large-scale violence (this has already happened to an extent), or trying to interfere with a free election. There is, of course, a lot of talk now about ways in which Trump is working to steal the 2026 midterms that we should be having in November. There may well be some crisis around those elections.

My hunch is that when that crisis comes, Trump’s side will lose. If, for instance, he tried to do something to subvert the elections, there would be riots in the streets to such an extent that he would have to back down—which, by the way, he usually does. Notice that on many of the worst things Trump does, he often ends up backing down. This has been true of the Greenland situation. Just yesterday, they announced they are pulling ICE out of Minneapolis. We’ll see if they actually do, but they have announced that. They have quietly pulled National Guard soldiers out of cities they had deployed them to, like Los Angeles and Chicago. They do not really admit they are doing that, but they have, in fact, done it.

Trump is a classic bully who is also weak, and when he meets pushback, he tends to retreat. So, if he tried, or when he tries, to do something questionable about the midterms this November, there will be pushback, and he will be forced off what he is trying to do.

To the other part of your question, Trumpism was not invented yesterday. This is a long current in American history. The ingredients that go into Trump and his constituency have manifested throughout American history. They appeared in the form of the Klan in the 1870s and again revived in the 1920s. They showed up in the form of Jim Crow in the South. They appeared in the form of McCarthyism in the early 1950s. This complex of nativism, racism, hostility to individual rights, and, to some extent, hostility to democracy has always been there in America. It is always going to be there. There will be a core of Trump supporters who will never abandon what they see him standing for. They may reach a point where they abandon him personally, perhaps—especially if there are further revelations from Epstein—but they will not abandon that package of ideas.

There will always be, whatever it may be, 20% or 30% of the American electorate attached to these ideas. My hope is that we can move toward a politics that contains it, so that we can still function as a liberal democracy where rights are protected, minorities feel safe, and we work with our allies. My hope is that we can contain it. I am somewhat optimistic that we can.

Telling Difficult Truths in a Polarized Age

And finally, Professor Hett, given your dual role as historian and public intellectual, how do you navigate the tension between scholarly restraint and moral urgency when historical patterns begin to rhyme in politically dangerous ways?

Professor Benjamin C. Hett: That’s a great question. I do wrestle with that a lot, to be quite honest. Sometimes I feel there are things I could say as a public-facing activist that I don’t really believe as a scholar, so I always feel that tension. I have been quite active in the last year or two. I was active in the election campaign last year with a group called Democracy First, which recruited a bunch of people like me—basically historians, political scientists, journalists, and so on—to speak about some of these issues and parallels at meetings and rallies, especially in swing states. So, I’ve been quite out there saying this stuff.

In a certain sense, to achieve the political effect I want—to rally people to democracy—I might be tempted to play up the threat more. I mean, I could say, oh, Trump’s super scary, he’s winning and so on, which I actually don’t believe. So, I try to be honest about that. I’ll give you another example of a tricky issue I navigate. I was actually just talking to some of my students about this the other day.

There are people on the right in America—Dinesh D’Souza is a prominent one—who argue that Nazism was a movement of the political left, not the right. People like D’Souza do this because they want to use that claim to discredit the political left in the present. They basically say, you liberals call Trump a Nazi, but actually you are the Nazis, and the Nazis were liberals and socialists like you, so you are the ones who bear this bad legacy.

Saying the Nazis were on the left is, in some basic way, wrong. In their time, the Nazis were seen as being on the far right by everyone in the political community. That’s why they found coalition partners on the right, why business and military elites were interested in working with them, and why the German Reich president, von Hindenburg, was willing to bring Hitler into government. They were seen as being on the right. However, it is also not entirely untrue that they drew some elements from the left. If you read the Nazis’ 25-point political program from 1920, there are many ideas that are quite congruent with a kind of social-welfare liberalism, if not something further left—profit sharing in big corporations, better health insurance programs, better educational opportunities for children from poorer backgrounds, old-age pensions, and so forth. There is a social-welfare element there.

And if you look at the name of the party—the full name was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party—if you took the “national” off and had a party called the Socialist German Workers’ Party, you would conclude that it was clearly a party of the left, probably a Marxist party. Once you add “national,” it becomes more complicated—complicated rather than coherently a party of the right. So, I feel, as a historian, that I need to acknowledge that complexity, even though I regret that this may give some oxygen to bad-faith actors like Dinesh D’Souza, who will say, “See? Even Hett says the Nazis were on the left.” That is the kind of thing I feel I am always navigating.

US President Donald Trump held a campaign rally at PPG Paints Arena in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on November 4, 2024. Photo: Chip Somodevilla.[/caption]

US President Donald Trump held a campaign rally at PPG Paints Arena in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on November 4, 2024. Photo: Chip Somodevilla.[/caption]