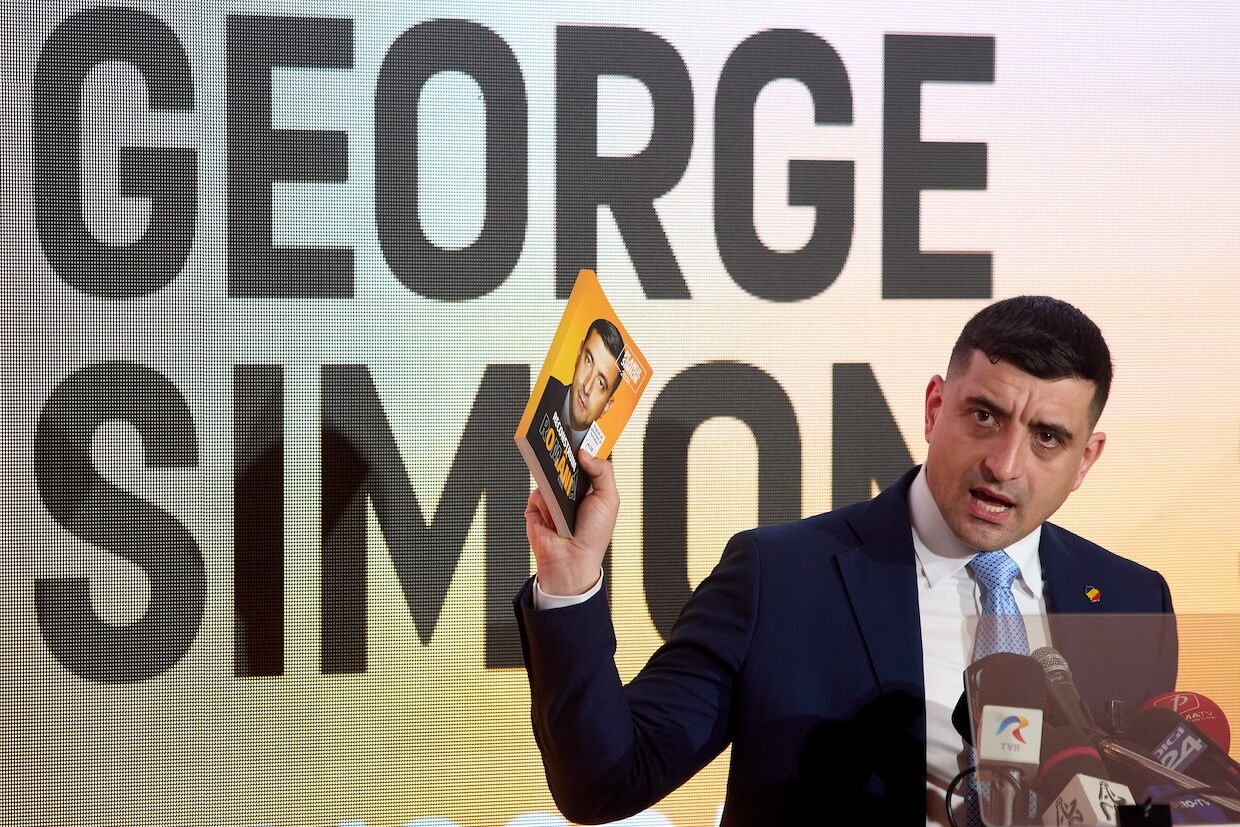

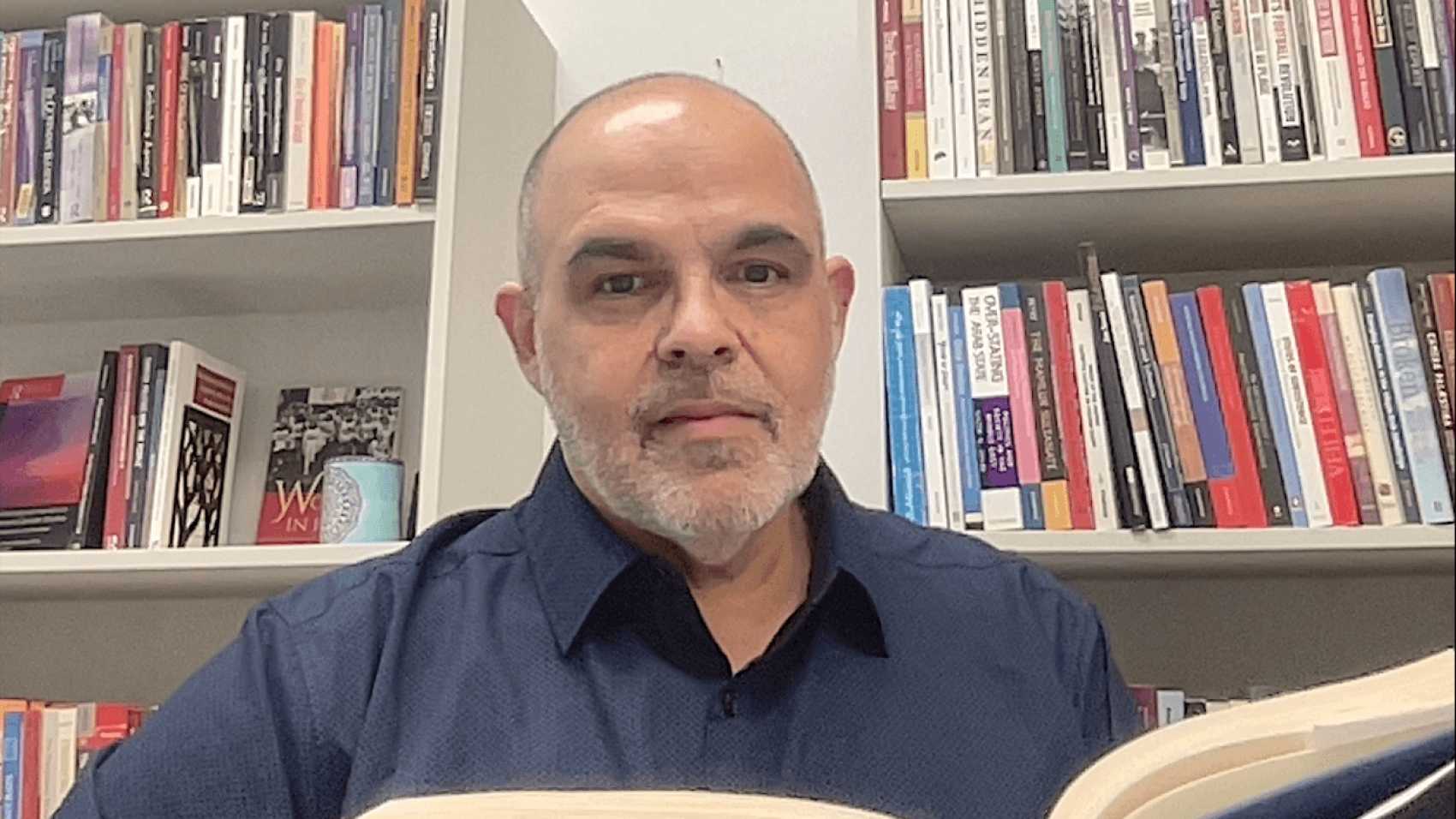

In this thought-provoking conversation, Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio—Gosling-Lim Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Michigan—discusses the resilience and transformation of populism in the Philippines. He explores how symbolic narratives of “pro-people, anti-elite” sentiment continue to drive support for dynastic figures like the Dutertes, despite mounting legal scrutiny. From social media toxicity to youth electoral shifts, Dr. Ragragio argues that populism is “here to stay,” shaped by local patronage networks and reinforced by mediatized political performance. He also highlights the importance of civic education and independent journalism as counterforces. This is a timely, incisive analysis of a political culture in flux.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In this wide-ranging and incisive interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio—Gosling-Lim Postdoctoral Fellow in Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Michigan—offers a sobering yet nuanced analysis of the enduring logic of populism in Philippine politics. With a research focus on media, democracy, and political communication in Southeast Asia, Dr. Ragragio traces how populist discourse and dynastic power have remained mutually reinforcing features of the Filipino political landscape.

“Populism in the Philippines is here to stay,” he affirms, stressing that whether “right-wing, illiberal, or left-wing-oriented,” such formations continue to thrive due to “an enduring clamor for pro-people, anti-elite sentiments” across both national and local arenas. This durability, Dr. Ragragio argues, is not merely rhetorical but structural, anchored in long-standing regional patronage networks and a media ecosystem conducive to symbolic politics.

Reflecting on the Duterte family’s electoral resurgence amid legal controversies—including former President Rodrigo Duterte’s detention at the ICC and Vice President Sara Duterte’s looming impeachment—Dr. Ragragio interprets this revival not simply as continuity, but as a strategic “recalibration of expressions of support” rooted in the “symbolic resilience” of populist narratives. Despite mounting legal and institutional scrutiny, he observes that “support can be sustained, especially at the local level,” even as national opposition gains ground.

Equally compelling is his analysis of political journalism as a contested discursive terrain. “Political journalism has long been a battleground,” Dr. Ragragio notes, shaped by both populist co-optation and democratic resistance. He commends outlets like Rappler and regional campus journalists for expanding critical coverage during the midterm elections, while also warning of the toxic political performance encouraged by algorithmic propaganda on platforms like Facebook.

Crucially, Dr. Ragragio identifies media literacy, civic education, and institutional accountability as key interventions in combating “authoritarian masculinity and political exceptionalism.” Yet he remains realistic about the persistence of dynastic dominance, noting that “a third of the Senate is composed of familial pairs.”

Ultimately, his insights reveal a landscape in flux—where democratic recalibration and populist entrenchment coexist in uneasy tension, and where the future of Philippine democracy hinges on how these competing narratives are mediated, institutionalized, and resisted from below.

Here is the lightly edited transcript of the interview with Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio.

From Continuity to Calibration: The Evolving Symbolism of Duterte’s Populist Appeal

Professor Ragragio, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: In the light of Rodrigo Duterte’s International Criminal Court (ICC) detention and Sara Duterte’s impeachment trial, how do you interpret the Duterte family’s electoral resurgence as a recalibration of populist performativity rather than a simple continuation of its earlier iteration?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: Thanks very much to the ECPS for this kind invitation. So, your first question really is a hard question already. Just to be clear for your audience—I’m not a political scientist, and I’m not a legal expert. My area really is in media and democracy. I’m particularly focused on news media and independent journalism in the Philippines, and I’m trying to expand that to Southeast Asian countries as well. But I’m very much interested in media populism, and I think this is one of the main thrusts of the ECPS.

Maybe before I go into details, I think it would help if I provide some very brief background about the Philippine midterm elections. We have just recently concluded the midterm elections in the Philippines. Normally, the midterm elections are less enticing compared to the national ones. Why? Because they are usually a referendum or a test of the trust or approval ratings of the current president or the current administration as a whole.

This midterm election that we just had is relatively more colorful—and perhaps some would say more historic—compared to past election cycles because the strong support for the current administration did not stand still. So, I think my key takeaway for this election is that, at least if we look at the national results of the Senate race, the midterm election results are somewhat bad for President Bongbong Marcos. But at the same time, they are also not so good for Vice President Sara Duterte, who is currently—and will eventually be—facing an impeachment trial at the Senate. So, that’s my main takeaway.

Regarding your question, there is obviously a resurgence of support for the Dutertes. If we look at both the national and the regional/local levels, you can see some clear indications that there is indeed a resurgence of support for former President Rodrigo Duterte, who is currently detained at The Hague at the International Criminal Court (ICC) for charges of crimes against humanity, and also for the political clan of the Dutertes in general.

The former President Duterte won the majority race very easily, and his children have also won virtually all key positions in the city of Davao. So, if the question is: Is there a resurgence? The short answer is yes. Is there a recalibration of expressions of support for the Dutertes? There were clear recalibrations—but there are also some emerging, more complicated, mixed expressions of support for the Dutertes.

Populism After Accountability

Does the Duterte camp’s sustained support reflect what you have elsewhere called the “symbolic resilience” of populist narratives, particularly in contexts where legal accountability coexists with popular legitimacy?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: It appears they can. It appears they can sustain this support from the city, from the regional publics, regional voters. But also, there are clear indications that this public support can be cut down— can be trimmed down.

Again, if we look at the national Senate race in the previous midterm elections, there is no clear and concise support going to the Dutertes, because this midterm election also opened opportunities for non-Dutertes—or anti-Dutertes rather—for supporters of the Liberal opposition, for example, which paved the way for the former Senators Aquino and Pangilinan to win this election cycle. So, yes, the support can be sustained, especially at the local level. But at the national or even regional levels, there might be some strong opposition—and consistent opposition as well—to the Dutertes.

To what extent does the Duterte revival indicate the adaptive strength of populist movements to institutional rupture and legal contestation? Can this be read as a post-accountability phase in Philippine populism?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: Oh, definitely. The resurgence, for example, of so-called young or youth voters—while we don’t yet have concrete data—appears to reflect a consensus among many observers that the youth vote delivered not for the Dutertes or the Marcoses, but rather for independent candidates who articulated strong platforms on governance issues such as agriculture, local livelihood, and basic education. So yes, the short answer to your question is also yes.

The resurgence, for example, of so-called young or youth voters—many of them, well, we have no concrete data yet, but it appears that many observers share a consensus that the young votes, or the youth vote rather, delivered not only for the Dutertes nor the Marcoses, but more on candidates—independent candidates—that spoke well of important platforms of governance, for example, agriculture, local livelihood, basic education, and so on. So yes, the short answer to your question is yes, as well.

Elite Rule in Anti-Elite Clothing

Considering the dynastic entrenchment of both the Dutertes and the Marcoses, how does Philippine populism mediate between elite familial power and its rhetorical positioning as anti-elite, anti-establishment politics?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: I’m not an expert in that field—I know there are scholars and political scientists who specialize in familial and patronage politics. But what I can say in response to your question is that anti-establishment expressions remain very much predominant—not only at the national level, but arguably even more so at the local and regional levels. For example, in races for the House of Representatives—what we call the “lower House of Congress”—and in contests for governorships, anti-elite and anti-establishment sentiments are widespread. And, not surprisingly, it’s often the same members of entrenched political families who deploy these very narratives. So yes, it’s a bit toxic, in a sense, to see how anti-elitism and anti-elite rhetoric continue to operate within regional and local elections.

How does the personalization of governance, exemplified by Sara Duterte’s political rhetoric and Rodrigo Duterte’s mayoral campaign from detention, reinforce the mythos of populist indispensability in Philippine political culture?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: I think the indispensability aspect of your question relates to the durable brand of politics—and populism in particular—in its right-wing or authoritarian form, which I would emphasize more. There is a clear sense of durability because, in the first place, the Dutertes have held political power in the city of Davao for over two decades. This style—especially its mediated, authoritarian populist expression—has significantly contributed to their continued dominance. And, as you mentioned earlier, several institutional aspects and barriers also reinforce their hold on power. Political patronage is one such mechanism. Moreover, the collaboration between and among political clans in local politics has been instrumental in sustaining this durable brand of governance in Davao.

The Marcos-Duterte Rift and the Strategic Deployment of Populist Performance

Is the current Marcos-Duterte schism a rupture within populist logic itself—or does it signal a competition over the same populist register of “strongman sovereignty” and “political vengeance”?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: I wouldn’t really call it a schism or a rupture in the context of populist politics because, first of all, it’s somewhat challenging to identify President Marcos as a populist. Of course, he has some expressions that could resonate or qualify as populist—such as being pro-people. But compared to the brand of populism espoused by former President Rodrigo Duterte, this isn’t really a schism between populist politics; it’s more about politics at large. For example, both President Marcos and Vice President Sara Duterte ran on a so-called platform of unity during the 2022 national elections. However, it only took them about a year—or even less—to realize that there was no unity at all in the brand of politics they had tried to project. So, while populism may not be at the forefront of the schism or rupture between the Marcoses and the Dutertes, if we define populism as an expression of how you resonate with the people—many segments of the public—this is where you can see the potential for both the use and misuse of populist politics.

In your analyses of editorial framing and mediatized nationalism, how has the news media contributed to either normalizing or contesting the discursive legitimacy of the Duterte camp’s post-presidency populism?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: Yeah, it’s a mixed bag. I haven’t yet expanded my study of editorials, but what I can say in relation to the recent midterm election cycle is that some independent news media outlets have done a commendable job of reporting. For example, if you look at the reporting by Rappler—an online news media platform—they expanded their coverage from the national level to include regional and local contexts. Covering regional and local elections has consistently been a challenge not only for national media outlets but even for local ones, largely due to a lack of sufficient manpower to cover election races in the provinces. But this time around, it’s commendable to see how media outlets collaborated with campus journalists—regional campus journalists in particular—who covered important local elections in their respective areas.

Toxic Platforms and Battleground Newsrooms

How would you assess the role of algorithmic propaganda networks, particularly on platforms like Facebook, in sustaining the Duterte narrative as a populist moral crusade amid institutional delegitimization?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: I haven’t looked systematically yet at the social media aspect of this midterm election. But I would surmise—based on my very cursory reading of Facebook pages or posts by politicians—that social media platforms, especially Facebook in the Philippines, represent one of the most toxic political environments you can think of. What I mean is that this is where you often see politicians, both national and local, trying to craft or reinforce certain images that will resonate with their target publics.

For example, what makes this environment particularly toxic is that you might see a senatorial candidate who would rather dance and capitalize on his showbiz celebrity charisma on stage than discuss his platform of governance. This is one aspect of what makes social media campaigning more problematic.

Of course, I do not deny that social media platforms can also serve as important avenues for grievances and for the expression of credible sentiments—especially among young voters—who may use these channels to voice their discontent against the administration or any politician, for that matter.

Has political journalism in the Philippines evolved into a form of discursive battleground, where journalists are not just observers but are increasingly cast as either custodians or co-conspirators within populist frameworks?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: I think political journalism in the country has been in that state for a long time. A quick backgrounder: Philippine journalism in general—the journalism environment—is regarded as one of the freest, if not the freest, practices of independent journalism in the region. Of course, there are many important and historical experiences by Filipino journalists that have shaped who they are and what they practice today.

So going back to your question, yes, political journalism has long been a discursive battleground for the expression of a variety of political sentiments. You have journalists who may support certain kinds of populist sentiments expressed by the Dutertes, but at the same time, you have journalists who are openly critical of the authoritarian populist sentiments of the leader. And then, of course, you also have some journalists—even some news media outlets—who are not so keen on expressing their political stance. Perhaps they prefer to observe, say, objectivity or nonpartisanship in the way they conduct their journalistic practices.

Courts, Congress, and the Contest for Accountability in a Populist Legal Order

Drawing from your work on media law and the judiciary, how do you evaluate the potential of institutions like the Senate and the Supreme Court to act as bulwarks against populist legalism—or are they being absorbed into its logics?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: I’d like to believe that—or at least have confidence in—institutions of checks and balances. For example, based on my work on the Supreme Court and press freedom in the country, I think there are avenues and strong potential for the Supreme Court to police and regulate extreme incivility coming from politicians and even from government officials.

In the case of the news media, as I mentioned earlier, there is also the potential for journalism—especially independent journalism—to express discontent and actively challenge illiberal politics and authoritarian populist sentiments. But I would go even further and consider the potential of other institutions. For instance, the role of the academia, of universities, and even credible polling or survey firms. These are critical institutions—critical organizations—that can contribute to building a more diverse and more democratic environment.

Is Sara Duterte’s impeachment trial a moment of institutional accountability or a spectacle of juridico-political theater shaped by dynastic rivalry? Given your analysis of the politicization of libel law, to what extent are legal instruments still being weaponized to manufacture legitimacy in the Duterte-Marcos power struggle?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: I think there are two main questions there. One has to do with the impeachment trial of the current Vice President. This is definitely an expression of accountability. One thing we need to look at is the upcoming impeachment trial at the Senate, which is scheduled for sometime in July—likely the last week. This will be broadcast live, making the proceedings publicly accessible. What this means is that public sentiment will figure significantly in the way the senators—the sitting senator-jurors—decide on the trial.

That’s one aspect. The other concerns the institutions. I understand there are related libel cases—not only against the Marcoses and the Dutertes, but also involving other politicians. That is something we need to keep a close eye on. Fortunately, there have been recent trends and initiatives by the Supreme Court to take more seriously the question: How exactly do we treat libel? And is there room for the decriminalization of libel as a criminal offense? Because in the Philippines, libel is a criminal offense. I believe we are one of the few countries—if not the only one—left in the world that still treats libel as a criminal offense. So that’s another important development to watch.

Democratic Pluralism from Below?

With the electoral success of figures outside the dynastic duopoly, such as Bam Aquino and Francis Pangilinan, do you perceive a nascent re-articulation of democratic pluralism—perhaps even a counter-populist discourse—emerging from below?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: I’d like to believe that way. I’d like to think that there is really great potential for the Liberal opposition to challenge the toxic brand of authoritarian populism. But at the same time, there are some unfortunate realities. For example, if you look at the upcoming composition of the Senate—we have 24 senators—and a third of them, so we’re talking about eight members, are related to one another. We have four pairs of senators who are siblings. This is really a kind of toxic politics that we need to be critical about. So your question about political dynasty, I hope, is one thing that can be tackled seriously by the resurging Liberal opposition in this election cycle.

What civic, educational, or legal interventions do you view as most urgent to disrupt the entrenched narrative of authoritarian masculinity and political exceptionalism in Philippine populist politics?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: That’s an important question, because we have a lot of discussion in the Philippines—and even in Southeast Asia—on how to combat mis- and disinformation. So, I think that is critical to both political education and even civic education. How, or to what extent, can media literacy develop our astute understanding of what a credible political brand or what a credible political, electoral campaigning slogan really matters.

Populism Is Here to Stay in the Philippines

Finally, in your view, does the 2025 midterm outcome represent a deepening of the populist-authoritarian paradigm—or does it contain seeds of democratic recalibration amidst an increasingly mediatized and dynastically polarized landscape?

Dr. Jefferson Lyndon D. Ragragio: Well, the short answer is yes to both your questions. First, I think populism is here to stay. I understand there’s a lot of scholarly and public discussion about what populism really is. In many European and American contexts, we tend to distinguish between right-wing populism, left-wing populism, or illiberal populism. In the Philippines, although those categories are present, I think we also see historically and politically distinct forms of populism that deserve more focused attention.

That said, to answer your question—populism in the Philippines is here to stay. Whether we are dealing with right-wing, illiberal, or left-wing-oriented forms, populism persists because there is an enduring clamor for pro-people, anti-elite sentiments that resonate strongly within both national and local political landscapes.