In an in-depth interview with the ECPS, Professor Sarah de Lange of Leiden University cautions that “D66’s victory in Dutch elections cannot be presented as a victory over populism.” While the liberal centrist D66 led by Rob Jetten revitalized the political center, Professor de Lange stresses that “the total size of the radical right-wing bloc has not diminished—it’s just more fragmented.” She argues that Dutch politics is shaped less by populism than by nativism, which has “seeped so much into the mainstream.” Despite the PVV’s exclusion from government, Professor de Lange warns that illiberalism remains a significant threat, while the defense of liberal democracy has only recently become “more salient for mainstream parties and more visible to citizens.”

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

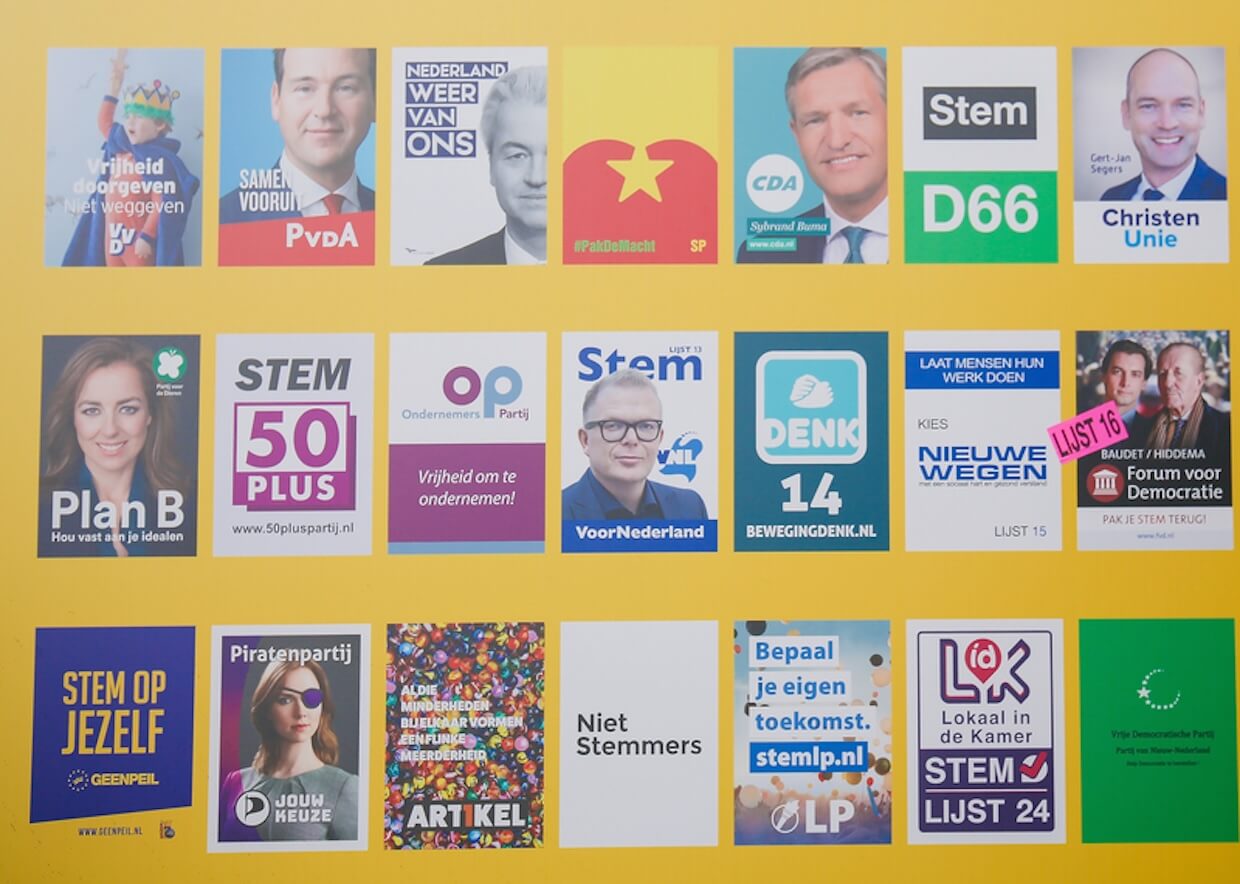

In a wide-ranging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Sarah de Lange, Professor of Dutch Politics at Leiden University’s Institute for Political Science, offers a sharp and nuanced interpretation of the 2024 Dutch elections, warning that “D66’s victory in Dutch elections cannot be presented as a victory over populism.” While the liberal centrist D66 emerged as the largest party, Professor de Lange argues that this outcome reflects both a revival of the political center and the continuing normalization of populist discourse within Dutch democracy.

According to Professor de Lange, the election results underscore a complex duality: “We can conclude that both things are happening at the same time.” Although centrist and Christian Democratic parties gained ground, the radical right bloc remains as strong as before—only more fragmented. This persistence, she notes, illustrates not the decline of populism but its adaptation: “The total size of the radical right-wing bloc has not diminished; it’s as strong as it was in the 2023 elections—it’s just more fragmented.”

Professor de Lange cautions against the view that the PVV’s losses signal a populist retreat. Instead, she interprets them through “traditional political science theories about governing and negative incumbency effects.” Geert Wilders’ participation in government, she explains, produced electoral backlash, but his influence on mainstream parties remains unmistakable—particularly regarding migration and national identity, now central themes even for the conservative-liberal VVD. “The VVD moved so close to the PVV in the campaign that it even supported some proposals by the radical right that had anti-constitutional implications,” she observes, underlining how populist narratives have reshaped the Dutch mainstream.

What truly defines this political transformation, Professor de Lange insists, is not merely populism but nativism. “It is this nativism that has seeped so much into the mainstream, rather than the populism,” she explains, pointing to the xenophobic nationalism that has become a structural feature of Dutch political discourse.

Reflecting on the broader European context, Professor de Lange rejects the notion that populism has been “domesticated.” Despite Wilders’ exclusion from coalition talks, she warns that illiberalism remains deeply entrenched. “There is still clearly a threat of illiberalism,” she notes, citing violent demonstrations and political intimidation during the campaign. Yet, she also detects a countermovement: “Defending liberal democracy and the rule of law has become more salient for mainstream parties… making citizens more aware of how vulnerable liberal democracy actually is.”

Ultimately, Professor de Lange’s analysis situates the Dutch case within the wider European struggle between liberal resilience and populist endurance, emphasizing that the current equilibrium represents neither populism’s decline nor liberalism’s triumph—but rather, a tense coexistence shaping the future of democratic politics in Europe.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Sarah de Lange, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

The Radical Right-Wing Bloc Has Not Diminished—Only Fragmented

Professor Sarah de Lange, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: The October 29 Dutch elections resulted in a striking balance between D66’s liberal centrism and Wilders’ populist radical right. From a comparative perspective, how should we interpret this outcome—does it mark a recalibration of Dutch democracy or the normalization of populism within it?

Professor Sarah de Lange: I think we can conclude that both things are happening at the same time. On the one hand, we’ve seen in the Dutch elections a revival of the center. Not only has the social-liberal D66 gained a lot of seats, but so have the Christian Democrats, and the two parties will be needed for any coalition government that will be formed. At the same time, we also see that Geert Wilders’ PVV has lost seats due to its government participation, but it has lost those seats to other radical right-wing populist competitors, namely JA21 and Thierry Baudet’s Forum for Democracy. So, the total size of the radical right-wing bloc has not diminished; it’s as strong as it was in the 2023 elections—just more fragmented.

Do you view the PVV’s losses as evidence of a populist retreat, or rather as a transformation of its discourse into the mainstream—particularly given the centrist parties’ increasing emphasis on migration and national identity?

Professor Sarah de Lange: The loss of the PVV should really be seen from the perspective of traditional political science theories about governing and negative incumbency effects. Geert Wilders’ PVV governed together with three other parties in the cabinet, and all four parties have lost to some extent in these elections. The loss of the PVV was significant, but perhaps not as large as one would expect for a party that participated in government. There’s a saying in politics that “the breaker pays,” and in this case, Geert Wilders did indeed pay—he did lose voters—but most of those he lost were voters who had joined his party only in 2023, when the VVD opened the door to the PVV.

Many previous non-voters turned out to support the PVV, given that there was finally a chance that the party would govern. So, it’s the newest voters of the PVV who have left again. But interestingly, although some of them came from the mainstream in 2023, few have returned to the mainstream in these elections. Some have—for example, to the conservative-liberal VVD—but in relatively small numbers, which explains why the radical right populist bloc is as strong as it was in 2023.

There’s also a second way in which Geert Wilders’ PVV has had a significant impact on these elections. All mainstream parties, and especially the conservative-liberal VVD, have taken up migration as the core theme of their campaigns and have advocated for a clear reduction in immigration, meaning stricter immigration regulations.

That has especially been the case for the conservative-liberal VVD of former Prime Minister Mark Rutte, now NATO Secretary General. The party moved so close to the PVV during the campaign that it even supported some proposals by the radical right with anti-constitutional implications. For example, Forum for Democracy, a smaller radical right-wing populist party, proposed during the campaign in Parliament that there should be a motion to designate Antifa as a terrorist organization—very much inspired, of course, by Donald Trump’s proposal to do the same. Even though Dutch legislation is very clear on this point—namely that it is up to the judiciary to designate organizations as terrorist organizations and not to Parliament—the conservative-liberal VVD nevertheless supported this proposal.

So, in that way too, the influence of radical right-wing populist parties in the Netherlands remains significant. What I’ve seen in much of the international press is that the victory of D66 has been presented as a victory over populism, but I certainly do not think it should be interpreted that way.

Nativism, Not Populism, Defines the Radical Right in the Netherlands

To what extent does the Dutch experience illustrate the idea of a “stabilized populism,” where populist rhetoric persists even as its organizational strength fluctuates?

Professor Sarah de Lange: It’s a clear case where we see a potential for the populist radical right that cannot be easily accommodated by the mainstream parties, in the sense that it’s very difficult for mainstream parties to win back voters who, at some point, have turned to the radical right. But I would also highlight that we tend to discuss this very much in terms of populism, while what has really been key to the transformation of Dutch politics—more than populism—is nativism.

What truly defines Geert Wilders’ political platform, as well as those of other radical right parties in the Netherlands, is their nativism, their xenophobic nationalism, and their othering of groups perceived as non-native—which, in the Dutch context, for the PVV, refers mostly to Muslims but more broadly includes anyone with a migration background, even extending to the third generation now living in the Netherlands.

It is this nativism that has seeped so deeply into the mainstream, rather than the populism. In fact, in this particular campaign, populism was not as pronounced in some of the radical right parties. Take, for example, JA21, which picked up a significant number of former PVV voters and could be involved in the coalition negotiations. The party remained clearly nativist in the campaign but was far less outspokenly populist, as a way to be more acceptable as a coalition partner—a serious partner—to mainstream parties.

Populism in Europe Has Not Been Domesticated or Contained

Looking beyond the Netherlands, what do these results reveal about the broader European and global trajectory of populism? Are we witnessing its institutional domestication or the emergence of a new post-populist equilibrium?

Professor Sarah de Lange: What we’re seeing is not its domestication. What was also very clear, already from the start of the campaign, was that Geert Wilders would not be acceptable as a coalition partner to mainstream parties for the next government. Some Dutch mainstream parties have said they don’t want to work with him on principle, because his program contains proposals that are not in line with freedom of religion and that conflict with the rule of law.

Other parties don’t want to work with him again because they don’t find him a trustworthy coalition partner, as he has now toppled two Dutch governments—the last one from which he withdrew, as well as the minority government that ruled the Netherlands from 2010 to 2012 with PVV support. It was therefore very clear to him that he would not be included in the government coalition again, and he immediately reverted to his strong populist and nativist rhetoric. Any moderation that existed during the coalition government—and there was very little of it—disappeared as soon as the coalition collapsed. So, certainly no domestication.

I also don’t necessarily think that we’re in a post-populist age. As I indicated, the radical right in the Netherlands remains as strong as ever, and what was particularly notable in the first survey data from the election is that the group of voters considering support for one of the radical right parties in the Netherlands has actually grown. The potential for the radical right to expand even further in future elections is therefore certainly there.

Wilders’ Personal Control Over the PVV Is Both His Strength and His Weakness

Building on your research on party agency and leadership, how do you assess the contrasting political performances of Rob Jetten and Geert Wilders—one mobilizing optimism and inclusivity, the other polarization and grievance?

Professor Sarah de Lange: These are two very different parties, of course, in terms of ideology but also in terms of party organization, and this is a very important part of the story for the Netherlands—one that sets it apart from other countries in Western Europe when it comes to the radical right.

Geert Wilders’ PVV joined the government in 2024, having had no significant experience with governing at the local or regional level. Why is that the case? For two reasons. First of all, Geert Wilders’ party does not have a traditional membership base. It is organized exclusively around the figure of Geert Wilders, who runs the party himself. It doesn’t have a membership base or a cadre. Even the representatives in the national parliament are not members of the party.

This means, first, that it is very difficult for him to participate in many municipal elections. He only participates in a select number of municipal elections, so there is very little opportunity for him to gain experience there. Secondly, it also means that people within the party have no executive experience—no experience with heavy management functions, etc.—and that there is no support staff within the party to assist those who need to take up government responsibility.

It was very evident in the cabinet that the PVV ministers, in particular, performed quite poorly on average. They didn’t know what their role was as ministers or junior ministers, how to deal with the bureaucracy, or how to bring legislation to a successful conclusion—meaning legislation that would be accepted by parliamentary parties and would actually be feasible, without including any anti-constitutional elements. So overall, quite poor performance.

That contributed to the early collapse of the government, because Geert Wilders saw that voters noticed this, and it is plausible that he withdrew from the government to avoid further electoral losses that might occur if voters became even more aware of how weak his pool of ministers was.

This really sets the Netherlands apart from other countries where the radical right can actually govern quite successfully because they have a trained cadre and local or regional experience. In that respect, if we compare the Netherlands to Italy, it is a completely different case.

Jetten’s Positive Campaign Reclaimed Hope and Unity

Jetten’s campaign drew on emotionally resonant, populist-style messaging—“het kan wél” (“yes, we can”)—without embracing populist antagonism. Does this signal that centrist liberalism is learning to compete in the emotional arena that populists once dominated?

Professor Sarah de Lange: Yes, this is a very interesting development that we’ve seen. D66 ran a campaign that was very positive in tone, speaking of hope and unity, and even went so far as to reclaim the Dutch flag as a symbol—quite surprising for a party that, in its stances, is extremely cosmopolitan and progressive, very pro-European Union, for example.

It seems that this approach worked, as it drew voters from other left-wing, progressive, and centrist parties. One explanation for this is that research shows having a genuinely positive atmosphere around a party can be beneficial in electoral campaigns.

Has Wilders’ long-standing personalistic leadership become both a strategic advantage and a constraint—particularly in terms of coalition-building and sustaining voter trust?

Professor Sarah de Lange: Yes, as I already explained, it’s certainly a disadvantage in one sense, as it makes it very difficult for the party to be ready for government—to have qualified and experienced people who can take up ministerial and junior ministerial positions. However, at the same time, it also offers him an advantage, in that he has full control over his members of parliament. So even though his parliamentary group grew significantly, since he controls which parliamentarians can speak to the media and on what topics, and in which debates they participate and in which they don’t, his parliamentary group didn’t experience any major scandals despite this massive growth in its size. Of course, one important element made this possible: Geert Wilders was not an acceptable prime minister to the parties with which his PVV governed, and he was therefore forced to stay in parliament as leader of the parliamentary group. Had that not been the case, it would have been much more difficult for him to control his members of parliament.

Current Exclusion of Wilders Is Pragmatic, not a Principled Cordon Sanitaire

In “New Alliances,” you analyze why mainstream parties sometimes collaborate with the populist radical right. Given the refusal of other parties to govern with Wilders, do current coalition negotiations represent a reinvigorated ‘cordon sanitaire’ or a temporary tactical alignment?

Professor Sarah de Lange: This is a very good question, because my research in the past showed that once radical right parties are large enough to help mainstream right parties achieve a majority, those mainstream parties are often inclined to govern with them, even if they might have said in advance that they were not interested or thought the radical right was too extreme to govern with.

What we’re seeing now in some countries—and that’s not only in the Netherlands but also, for example, in Austria—is that, on the basis of previous coalition experiences with the radical right, the picture has become more complex. There are a number of mainstream right parties that have had such bad experiences governing with the radical right that they are no longer willing to do so.

However, I think this is very different from a cordon sanitaire, because a cordon sanitaire is motivated by a principled rejection of the radical right on the basis of its stances—because the manifestos of the radical right contain nativism and proposals that are anti-constitutional or in conflict with the rule of law. What we see here, in both the Austrian and Dutch cases, is that the reluctance is based more on the fact that previous experiences have shown that radical right parties are unreliable partners. And of course, that is a more pragmatic argument, which can also be abandoned—for example, if the radical right gets a new leader who is believed to be more trustworthy, or if the mainstream right changes leadership and feels differently about cooperating with the radical right.

So, in that sense, we should really keep these pragmatic reasons separate from the more principled exclusion represented by a cordon sanitaire.

Exclusion Strengthens Wilders’ Anti-Elite Narrative Among Supporters

What are the long-term risks and benefits of excluding the PVV from coalition governance? Could such exclusion paradoxically reinforce its anti-establishment narrative, as observed in other European contexts?

Professor Sarah de Lange: This is a very valid question. Of course, the advantage is that there will be no negotiations about plans that are anti-constitutional. If we look at the previous cabinet, of which the PVV was part, that cabinet tried to declare an asylum crisis in order to introduce emergency legislation that would partially circumvent Parliament. That would have been a clear sign of democratic backsliding if it had happened. Luckily, some of the government parties changed their minds at the last minute, and it never came to fruition—but the idea was clearly on the table. Without the radical right in government, there is, of course, far less likelihood of these kinds of plans being implemented.

The downside, however, is equally clear. Excluding the PVV makes the rhetoric of the radical right more believable—namely, the idea that there is an elite governing the country that is out of touch with what citizens want because it excludes the radical right, which also represents a part of the population. In the Netherlands, this risk is particularly real, because the only four-party coalition capable of securing a majority would be a very broad ideological alliance, ranging from the Green Labour Party to the social-liberal D66, the Christian Democratic CDA, and the conservative-liberal VVD. Such a coalition, both on socio-economic issues and on matters like immigration, would have very different positions and would need to compromise extensively—only reinforcing the PVV’s narrative that it alone stands outside an isolated political elite.

The Netherlands Could Learn from Scandinavia’s Clear Left–Right Blocs

How might a centrist, multi-party coalition led by D66 influence the structure of competition in Dutch politics? Could it serve as a model for containing populist disruption in fragmented systems elsewhere?

Professor Sarah de Lange: I don’t think it’s a model to be emulated; it’s a model that exists only because the Dutch parliament is so fragmented. The largest parties are very small— even D66, which became the largest party in the elections, holds less than 20% of the votes and seats. The same applies to the other parties likely to join the coalition, each of which has around 15% of the vote. This makes the structure of the Dutch party system highly untenable in the long term, as it requires four- or five-party coalitions, which would have been necessary even if the PVV had not been excluded. Such coalitions are very likely to be unstable, leading to short-lived governments and limited policy output.

So, I think it’s actually the other way around. Looking across Western Europe, the Netherlands could benefit greatly from having a structure more like a Scandinavian party system, with a clear left-wing and right-wing bloc, rather than the highly fragmented system it currently has to manage.

Weak Party–Society Links Drive Extreme Electoral Volatility

Your work on party–civil society linkages shows that strong organizational ties stabilize voter support. Does D66’s success suggest that centrist parties can rebuild civic connections that were eroded by decades of depoliticization? Conversely, how does the PVV sustain long-term voter loyalty despite its limited organizational infrastructure and weak civic embedding?

Professor Sarah de Lange: Let’s start by observing that in the Netherlands, political parties generally have weak linkages to civil society organizations, and this partly explains why Dutch elections are so extremely volatile—they are among the most volatile in Europe.

What’s interesting is that the two largest parties in the elections, D66 and the PVV, are both known for lacking many of these traditional ties. This indicates that while they may be very successful in a given election, they could just as easily lose that support again. This applies especially to D66, which has always been a party marked by very high highs but also very deep lows. It has an extremely volatile electorate that also considers many other left- and right-wing progressive parties at election time.

The PVV is slightly different. It has no ties to civil society organizations at all, yet it has a remarkably loyal electorate that remains faithful to the party for several reasons. First, PVV voters genuinely believe that Wilders is the only person who can change immigration policy in the way they want. Election surveys show that 90% of PVV voters view immigration as the biggest social challenge the Netherlands faces, and they see Geert Wilders as the most competent and trustworthy politician to act on that issue. Second, these voters tend to have relatively high levels of political distrust, which makes them unlikely to return from the PVV to mainstream parties.

PVV Support Is Strongest Outside the Cosmopolitan Randstad Region

How much of the PVV’s enduring appeal still stems from regional and class-based resentment, and how much from broader cultural anxieties related to immigration and demographic change?

Professor Sarah de Lange: I think both are connected. We see that Geert Wilders’ PVV is more successful outside the big cosmopolitan cities in the Randstad—the central area enclosed by major cities such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Utrecht. The PVV performs better beyond that region. This is partly due to a sense of regional resentment—the perception that people in areas where the PVV is strong are not being taken seriously by the political, economic, and cultural center of the Netherlands; that they are not adequately represented; and that there is little respect for their norms, values, and traditions.

These feelings are also partly rooted in real developments in these regions, such as economic decline, the out-migration of young citizens, and the erosion of public and private services. So, even though there may not be many migrants in these areas, these socio-economic developments feed into anti-immigrant sentiment—not least because Wilders consistently draws links between immigration and other social problems.

Jetten to Become the Netherlands’ First Openly Gay Prime Minister

In your co-edited volume “Gender and Populist Radical-Right Politics,” you highlight the gendered dimensions of populist leadership. How do you interpret the symbolic contrast between Wilders’ assertive, masculine populism and Jetten’s inclusive liberal masculinity?

Professor Sarah de Lange: That’s a very interesting question, because the Netherlands will, with Rob Jetten, have its first openly gay prime minister, who is about to marry his male partner. He has always been very open about this, and it was an important element in the campaign, where he frequently spoke about his upcoming wedding. This stands in stark contrast to the traditional masculinity promoted by Wilders, and even more so by Forum for Democracy’s Thierry Baudet.

Interestingly, in terms of voter base, we see that the PVV—now that it has become such a large party—is actually quite representative of the Dutch population as a whole, including in terms of gender. We don’t see a strong gender gap among its voters, unlike with the more extreme Forum for Democracy led by Baudet. It therefore seems that female voters are not put off by Wilders’ masculine leadership style, nor by a party program that is not particularly outspoken on gender issues.

LGBTQ Acceptance Is Central to the Dutch National Self-Image

Does the normalization of openly gay political leadership in the Netherlands challenge the gendered and heteronormative foundations of populist radical-right discourse, or does it reflect a uniquely Dutch liberal exceptionalism?

Professor Sarah de Lange: This is quite an interesting question. During the campaign, it was clear that Geert Wilders could not realistically attack Jetten on the basis of his sexuality or the fact that he is marrying his male partner. This is because a core part of the Dutch national self-image is its perceived tolerance toward the LGBTQ community.

That does not mean, however, that PVV supporters share this perspective. They have very mixed attitudes when it comes to LGBTQ issues. Of course, since same-sex marriage has been legal for a long time, there is little resistance to it. But when questions turn to more contemporary sexuality issues—such as trans rights or stances on non-binarity—you can see that these voters tend to hold a very heteronormative outlook.

Radical Right Strength Shows Illiberalism Remains a Persistent Threat

And finally, Professor de Lange, does the Dutch election signal that liberal democracies are learning to integrate populist affect without embracing its illiberal impulses—or are we entering a phase of hybrid politics where the emotional grammar of populism becomes a permanent feature of democratic life?

Professor Sarah de Lange: The elections show that, because the radical right remains so strong, illiberalism is still present—and it was very visible in the campaign as well. There were incidents involving extreme-right demonstrations that turned violent, and numerous cases where politicians were threatened by political opponents or ordinary citizens with different political opinions. So, in that sense, there is still clearly a threat of illiberalism.

At the same time, this particular campaign also demonstrated that defending liberalism—or liberal democracy, and the rule of law has become more salient for mainstream parties, especially among more progressive forces. The issue is now more openly discussed, making citizens more aware of how vulnerable liberal democracy actually is, and that it is something that must be safeguarded rather than taken for granted.