Highlighting Elon Musk’s dual role as a private tech mogul and a potential quasi-governmental leader under elected US President Donald Trump, Professor Anthony J. Nownes underscored the dangers of unregulated private power intersecting with public institutions. He emphasized that ceding excessive power to any private interest—whether in the tech industry or another sector—poses a significant threat to democracy. Illustrating this concern, Professor Nownes pointed to the proposed “Doge Department,” noting, “Unlike actual government departments with conflict-of-interest rules, such private entities lack safeguards, making them a potential avenue for unchecked influence over public resources.”

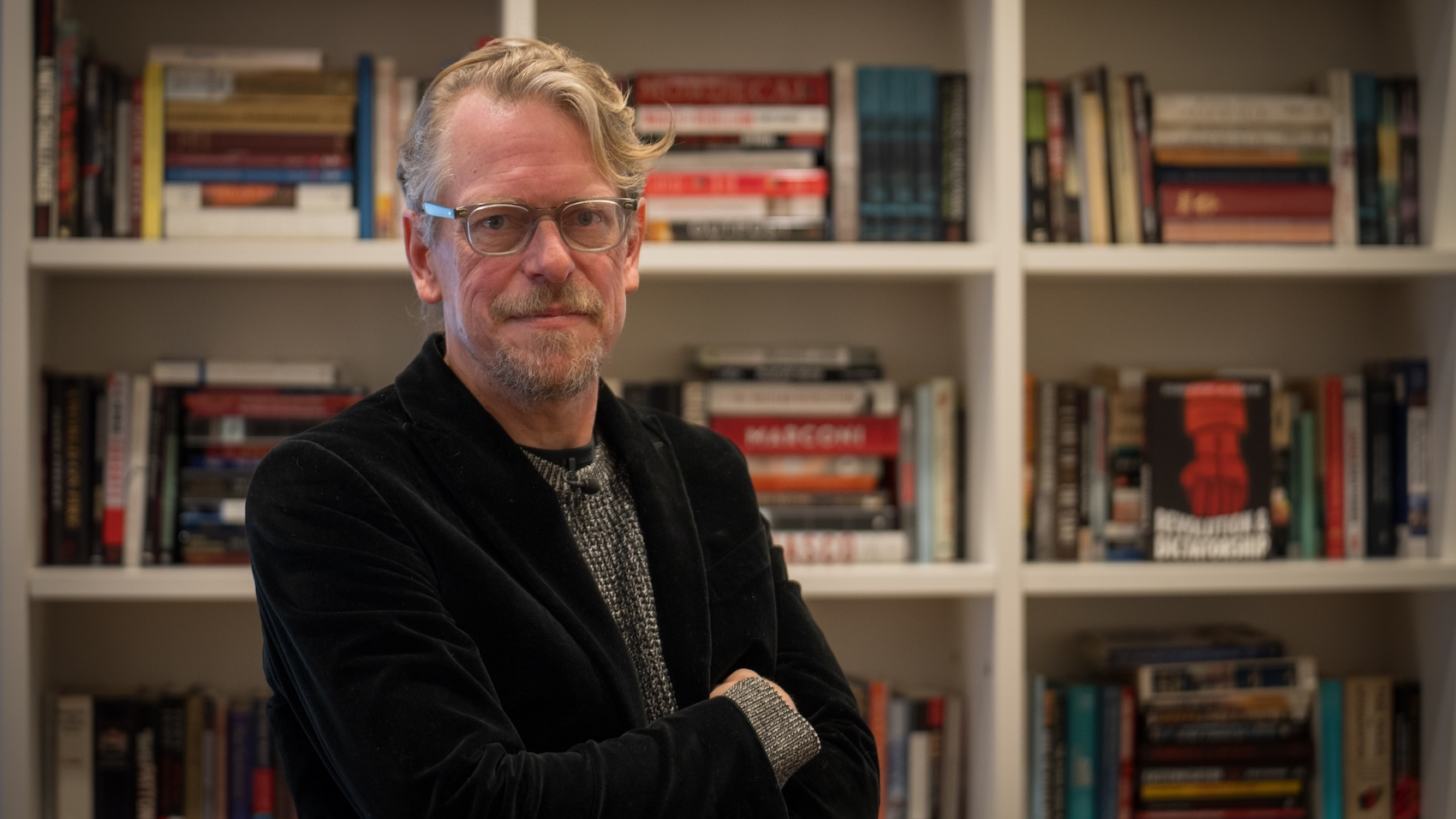

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

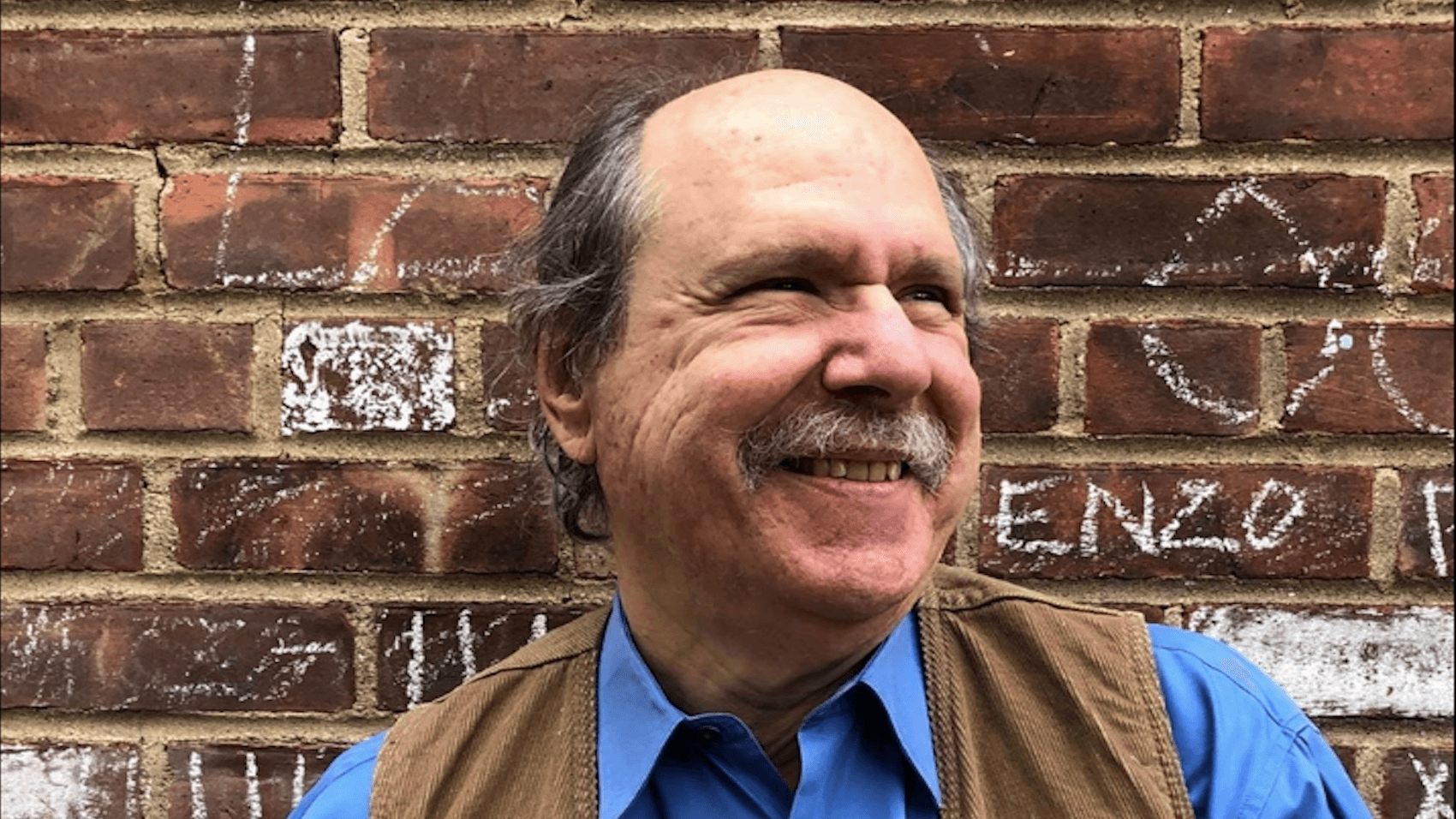

In an illuminating discussion with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Anthony J. Nownes, a political science expert from the University of Tennessee and co-author of the book titled The New Entrepreneurial Advocacy -Silicon Valley Elites in American Politics, offered his insights on the growing influence of tech elites and its implications for democracy. Centering on the theme of the delicate balance between private power and public accountability, Professor Nownes emphasized a pressing concern: “Ceding too much power to any private interest—whether the tech industry or any other sector—poses a threat to democracy.”

Highlighting Elon Musk’s dual role as a private tech mogul and a potential quasi-governmental leader under elected US President Donald Trump, Professor Nownes pointed out the dangers of unregulated private power intersecting with public institutions. He explained, for instance, the risks of the proposed “Doge Department” (or Department of Government Efficiency), stating that “unlike actual government departments with conflict-of-interest rules, such private entities lack safeguards, making them a potential avenue for unchecked influence over public resources.”

Turning to the broader historical context, Professor Nownes compared today’s tech moguls to past industrial giants. While corporate influence is not a new phenomenon, he argued that the tech industry’s vast resources and rapid innovation—outpacing government regulation—make its impact unique. Using examples like Microsoft protecting Ukraine from cyberattacks and SpaceX ensuring Ukrainian connectivity, Professor Nownes highlighted how tech companies wield unprecedented power over geopolitical and societal outcomes.

On the issue of lobbying and political advocacy, Professor Nownes delved into the disproportionate focus of Silicon Valley philanthropy on post-material causes, such as environmental conservation and DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion), rather than structural inequalities. He warned that this prioritization risks sidelining critical issues like income inequality and homelessness, leaving a vacuum often filled by populists like Donald Trump, who, while lacking substantive solutions, at least address these concerns rhetorically.

Professor Nownes also discussed the erosion of public trust in tech companies, exacerbated by scandals such as Cambridge Analytica. Referencing a Pew study that found 78% of Americans believe social media companies wield too much political power, he noted that despite this skepticism, tech giants have not yet faced significant political or economic repercussions. However, he foresees this changing, particularly as ethical considerations—such as the negative effects of social media on children—gain political traction.

Professor Nownes also addressed the future of American democracy under a second Trump administration. While cautiously optimistic about its survival, he acknowledged the erosion of democratic norms and the slow response of legal institutions to recent challenges. His reflections offer a sobering reminder of the delicate equilibrium between private power and public accountability, as well as the need for vigilance in preserving democratic principles in the face of rapid technological and political change.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Anthony J. Nownes with some edits.

Tech Titans Shape Public Discourse by Spotlighting Key Issues

Professor Nownes, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question. How do you view the growing influence of tech elites in shaping political agendas? Are they effectively becoming a new form of political aristocracy? How has the concentration of economic power among tech giants influenced the balance of political power in the United States? Could you discuss whether their dominance undermines or enhances democratic institutions?

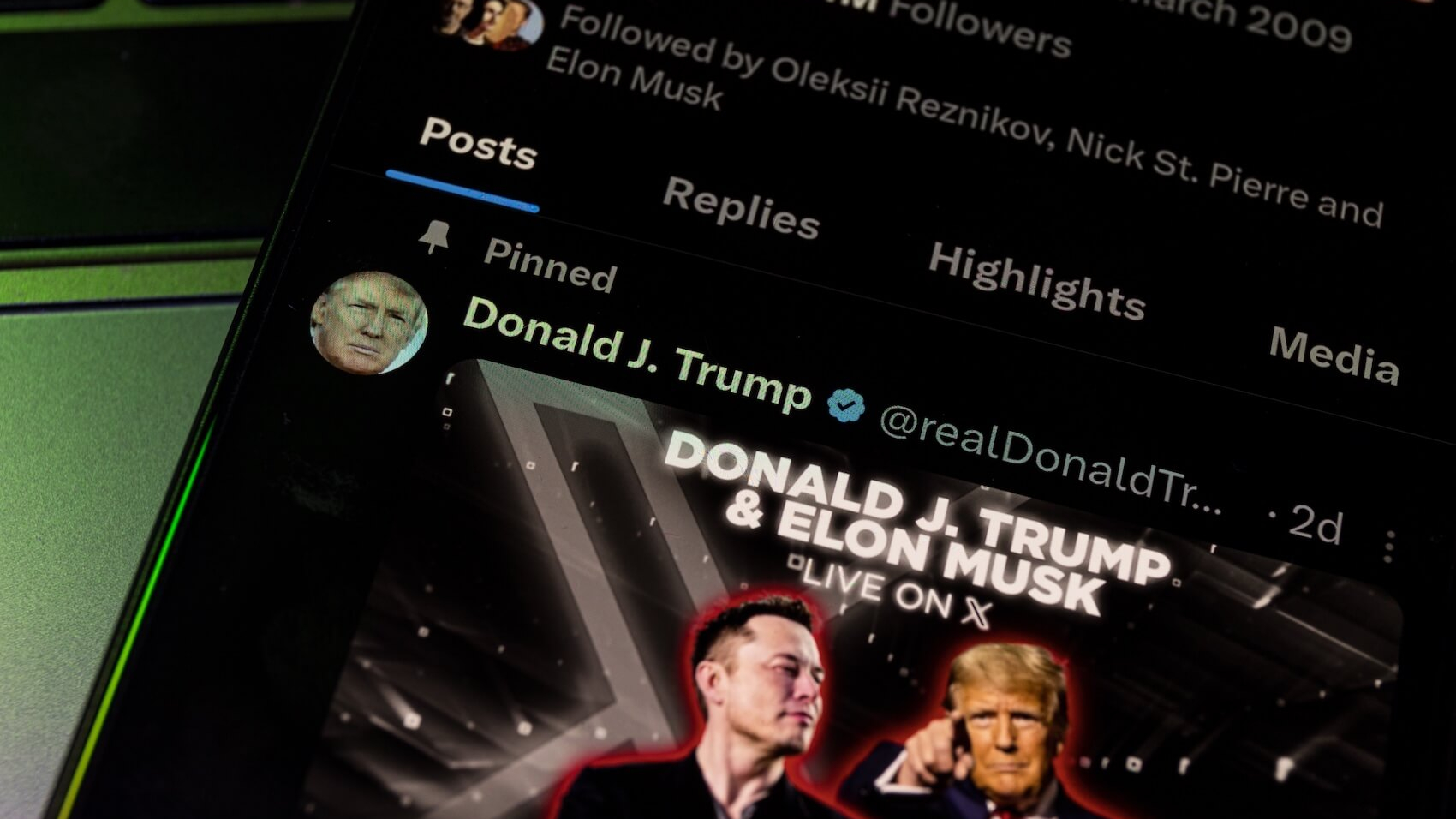

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: First of all, thank you for having me here today. I appreciate the opportunity. I’m glad you phrased the first part of your question the way you did, focusing on agendas rather than policy outcomes. This distinction is important. There’s no question that tech elites shape the political agenda. Let’s start with Elon Musk. He’s the wealthiest man on earth and commands significant media attention for almost anything he does. Beyond that, his direct involvement in media platforms like Twitter—now X—and others like Instagram amplifies his influence. His posts, or whatever they’re called now, and his public statements certainly affect which issues people think about.

This doesn’t necessarily mean people agree with him, but it does mean they see what he says and often recognize the issues he highlights as important. Elon Musk is not alone in this regard. Other tech elites—Mark Zuckerberg, Reid Hoffman, Tim Cook, and many others—also have massive social media followings. While they may not always achieve their desired policy outcomes, there’s no doubt that the issues they publicly engage with are those that garner significant public attention. In this way, they have considerable success in shaping the political agenda.

Now, regarding the second part of your question about the concentration of economic power, these are, of course, challenging questions to answer definitively. Speaking both as a scholar and a citizen, I would argue that whenever the government cedes too much power to private actors, it risks undermining democracy. The government should and must work with private actors—after all, in a capitalist system, the economy’s health depends largely on the private sector’s vitality. But the government has its own role here, and at least theoretically, that role is to look out for the rest of us. I believe that ceding too much power to any private interest—whether the tech industry or any other sector—poses a threat to democracy. To demonstrate this, let me highlight some of the perils of granting excessive power to private actors.

Take, for example, the so-called “Doge Department.” You may not be familiar with this, but it’s the quasi-governmental body Donald Trump has claimed he has already begun forming. Officially called the Department of Government Efficiency (I use air quotes because it’s not actually a government department), it’s essentially a quasi-governmental—or really, a non-governmental—organization. Trump has reportedly chosen Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy to head it, with the stated goal of making the government more efficient.

Real government institutions, agencies, and bureaucratic departments operate under strict rules and regulations. These rules dictate who they can hire, what sorts of behavior are and are not allowed in the workplace, the qualifications required for employment, and, crucially, who the department is accountable to.

Now, imagine this organization gets up and running. Suppose, within six months, Trump grants it actual power. There would be little to stop someone like Elon Musk from making decisions that, for example, ensure his companies receive lucrative government contracts while his competitors do not. Unlike actual government departments, which have conflict-of-interest rules and similar safeguards, a private, non-governmental organization like this lacks such mechanisms.

This is one of the clearest examples of what could go wrong when excessive power is given to private actors within a democratic system. It underscores the importance of maintaining strict oversight and clear boundaries between public institutions and private entities to preserve the integrity of democratic governance.

Power of Tech Giants Today Is Unprecedented Compared to Past Corporate Interests

Frederic Legrand.

Looking at the historical relationship between corporate power and politics, how does the role of hi-tech oligarchs compare to past industrial moguls in shaping American political landscapes? Is this a continuation of corporate influence, or does the unique nature of digital platforms present new challenges?

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: For the first part of your question, I’d like to preface my response by acknowledging that I’m not a historian, so I hesitate to draw extensive comparisons between current tech oligarchs and past industries in American politics. That said, it’s certainly not unprecedented for a powerful industry to wield significant influence over political outcomes in this country.

For instance, every school kid in the US learns about the robber barons of the Gilded Age. Additionally, the tobacco industry wielded extraordinary political power for decades, successfully staving off serious regulation of tobacco products. Throughout US history, doctors, the insurance industry, and other healthcare providers have collectively spent immense amounts of money lobbying against socialized medicine, with considerable success. So, corporate influence in politics is nothing new—it has been a feature of the American Republic from its very beginning.

However, I think it’s worth noting that the tech industry is different in several respects from previous industries that wielded political power. One key difference is the almost unfathomable resources these companies possess. As an industry and even at the individual company level, tech entities have significantly more wealth and resources than many nation-states. This is unprecedented.

Another difference is the rapid pace of innovation within the tech industry, which often outpaces the ability of governments and regulatory agencies to keep up. For example, SpaceX is currently more capable than the US government when it comes to space exploration. Similarly, Alphabet (Google) is far ahead of the US government—and likely any other government—in developing and deploying artificial intelligence. This gives tech companies tremendous influence over our lives, even if that influence is not overtly political.

I believe the rise of the tech industry introduces challenges that are different from those posed by previous corporate powers—some of which we may not even fully understand yet. For instance, consider the war in Ukraine. Tech companies are not directly involved in the conflict, yet they are significantly affecting events on the ground. Microsoft, for example, protects Ukraine from cyberattacks. SpaceX ensures that Ukrainians remain connected to the Internet. I recently read that Google has removed images of Ukraine from its open-source maps. These actions, while not traditionally political, have a profound impact on real-world political and international events. In this sense, the power of the tech industry over people’s lives is unprecedented compared to the influence wielded by previous corporate interests.

‘Leave Us Alone’ Ethos Shapes Platforms and Policies

How do hi-tech firms’ lobbying activities compare to other industries in terms of expenditure and focus? Specifically, what does the dominance of issues like taxes, intellectual property, and technology indicate about their priorities in shaping US policy? How does this concentrated influence by a few tech giants affect policymaking transparency and public interest considerations?

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: I certainly understand why both the media and ordinary people are focusing on tech lobbying and the political influence of big tech. However, I think it’s important to recognize that the tech industry is just one of many industries in this country that spend hundreds of millions of dollars every year attempting to influence policy and elections.

There are other perennial heavyweight industries that spend on a similar scale to the tech industry. For example, the pharmaceutical industry, the health insurance industry, securities and investment companies, and the oil and gas industry are all highly politically active and spend significant sums. In that sense, the tech industry is not fundamentally different from other high-profile, politically active industries.

As for your final question, I found it interesting the way you phrased it. I study what we call public interest groups or non-governmental organizations in this country, which are comprised of individual members. At this point, there simply aren’t many public interest groups—or what we might also call citizen groups—working on the opposite side of the issues that big tech is pushing.

In many other industries, there are countervailing groups. For instance, in the oil and gas industry, there are hundreds of environmental groups in the United States. While they don’t have the same resources as oil and gas companies, they’ve managed to achieve a number of political victories over the past several decades. Similarly, healthcare and pharmaceutical companies often contend with public interest groups—especially senior citizen organizations—that lobby against them on issues like the cost of prescription drugs and government programs. Currently, I don’t see many public interest groups or citizen groups actively working to counterbalance the power of big tech. This, I believe, is another way in which this corporate sector is somewhat unusual.

What role do tech oligarchs play in shaping public discourse, and how do their personal ideologies influence the policies and practices of their platforms? Are we witnessing a new form of political lobbying through algorithmic curation and platform management?

Professor Anthony Nownes: This question seems almost perfectly shaped to refer to Elon Musk. Certainly, his personal ideology seems to affect every aspect of his newest company, X. I think there’s an element of this influence among other tech moguls as well.

It’s a cliché, but I believe it’s accurate to say that many of these individuals, even those who have traditionally supported center-left or left causes and the Democratic Party, are at their core economic libertarians. They are libertarians on social issues as well, but their general ethos of “leave us alone and let us do what we want” seems to permeate how they run their companies. I’m particularly thinking here of platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and X. It doesn’t take much time spent on these platforms to realize that a fairly libertarian ethos influences what happens on them.

As for your second question, I’m not entirely sure I know enough about algorithms and platform management to say much definitively. However, I can say this: it seems to me that the conservative criticism these companies faced during the first Trump administration did affect some of their practices. For example, this criticism likely influenced content moderation policies, decisions to label certain material as misinformation or disinformation, and determinations about who to platform and who to de-platform. So, I do think there is some evidence that algorithmic curation and platform management are having political effects.

Social Media Companies Contribute Significantly to Misinformation Epidemic

Given the rise of misinformation and polarization on social media platforms, do you believe tech companies bear responsibility for mitigating these issues, or should this be addressed through government regulation? How do we balance such regulation with the principles of free speech?

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: I’m not sure this is exactly how the question was intended—but I’ll answer it this way regardless, more as a citizen than as a scholar. Social media companies absolutely bear some responsibility for the explosion of misinformation and disinformation in this country. Of course, they don’t see it that way, but I think the evidence is overwhelming that they have contributed significantly to the epidemic of misinformation and disinformation in the US and elsewhere.

No matter how one feels about government regulation, it seems to me that there’s really only one entity in this country large enough, powerful enough, and well-resourced enough to rein in these companies: the federal government. The EU, of course, also has the capacity to impose regulations. However, these companies have shown very little commitment to addressing misinformation and disinformation on their own, so I see the idea of self-regulation as a bit of a nonstarter.

As for the free speech aspect of the issue, I don’t think balancing regulation with free speech is particularly difficult. We already do it all the time in other domains—for example, with tobacco advertising. I think the free speech defense offered by social media companies to justify their conduct is, frankly, somewhat nonsensical. We regulate many things in society without infringing on people’s rights to express themselves or act within legal boundaries.

Do you think the political donations and lobbying efforts by Silicon Valley’s tech executives disproportionately sway policy outcomes? Are there examples where their influence has significantly impacted legislation or political campaigns? With federal campaign finance laws being described as “byzantine and ever-changing,” what challenges do these laws pose in regulating the contributions of tech leaders, and how can these challenges be addressed without infringing on free speech rights?

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: Before addressing this question directly, I want to point out something that may already be familiar to many of you: for those of us who study interest groups, corporate influence, or lobbying, determining influence is incredibly difficult. The primary reason is the old adage: correlation does not equal causation.

For example, in the US, we see the gun lobby making significant contributions to right-leaning politicians, who then work diligently to maintain access to firearms. However, this doesn’t necessarily prove influence because these politicians likely would have acted the same way without the gun lobby’s financial support. Indeed, that alignment is often why the gun lobby supports them in the first place. As a result, proving policy influence is challenging, and at best, we can make educated guesses based on available evidence.

That said, it’s clear to me that the tech industry, like many others, has been highly influential politically. One prominent example is the tech sector’s campaign to preserve Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. This legislation protects online platforms from being treated as publishers, granting them virtual legal immunity for content posted on their sites—a unique advantage in US law. Social media companies have invested significant time and resources at both the state and federal levels to ensure Section 230 remains intact.

Another notable example is Proposition 22 in California. Uber and Lyft spent substantial sums to secure their exemption from labor laws in one of the country’s most liberal states. Similarly, big tech firms, including Amazon, have successfully resisted legislation aimed at increasing transparency about how user data is utilized. On the individual level, tech leaders like Peter Thiel have played pivotal roles in the political ascendance of figures such as J.D. Vance.

As for the second part of your question about campaign finance laws, I think it’s essential for people to realize that campaign finance laws in this country, as they are currently configured, really can’t stop an individual or organization from pouring as much money as they want into our campaign finance system. Yes, there are regulations, and yes, these regulations can and do prevent the ultra-rich and well-resourced organizations from donating money directly to candidates for office. However, the way the laws are currently structured—and I don’t see this changing anytime soon—there is nothing the government or anyone else can do to stop a person or organization from spending unlimited sums of money to support candidates or parties they favor.

For example, Elon Musk reportedly contributed something between $200 and $300 million to help Trump get elected. He’s not allowed to give that money directly to Trump, as the amount he can donate directly to a candidate is severely limited. But he is allowed to give that money to a Super PAC. In this case, he contributed to his own Super PAC, “America PAC.” All he had to do was hire one or two competent lawyers to ensure they followed the letter of the law, and there was nothing to stop him from funneling unlimited sums of money into the election.

I see no evidence at all that either major political party has any appetite to change anything about the current system. As such, I view the question of regulating this kind of spending as rather moot. I do not see any significant reform in this area on the horizon.

Most People Are Getting All Their News from Podcasters

You discuss “super citizens” leveraging their wealth and public profiles to influence policy through media and social platforms. How do you see this form of direct advocacy evolving, especially with the growing influence of social media as an unmediated channel?

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: I’m not particularly skilled at predicting the future of politics, and I don’t feel I know enough about technology to provide a deeply insightful answer to this question. However, after reflecting on it, I can offer the following observation: One trend my co-author, Darren Halpin, and I have noted regarding the concept of “super citizens” is that an increasing number of people—particularly younger individuals, and especially younger men—are receiving all of their news, not just part of it, from individuals who are not traditionally part of the news industry. Figures like Joe Rogan and Theo Vaughn, for instance, are immensely popular podcasters who exemplify what we term prototypical super citizens. These individuals initially gained fame through non-political activities but now wield considerable political influence through their podcasts.

I think the extent to which people rely on these sources for news and information is somewhat underappreciated. As traditional or legacy media continues to decline in importance, and in some cases disappears altogether, I believe we’re going to see much more of this phenomenon. Unfortunately, as a result, disinformation and misinformation are likely to become even bigger problems moving forward.

Your book suggests that Silicon Valley philanthropy tends to favor postmaterial causes, such as environmental conservation and arts, over redistributive efforts that address economic inequality. What implications does this trend have for addressing structural inequalities in American society?

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: The first part of the question addresses disproportionate funding for certain issues. A good example here is education. Our research showed that Silicon Valley figures and their foundations have spent considerable amounts of money over the past couple of decades on what they call education reforms—initiatives such as charter schools, privatization, and voucher schemes. There’s substantial evidence that this advocacy, and in some cases direct funding, has influenced state policies and school districts across the United States. This demonstrates how Silicon Valley’s prioritization of certain issues over others can have significant impact, though it remains challenging to definitively prove causation.

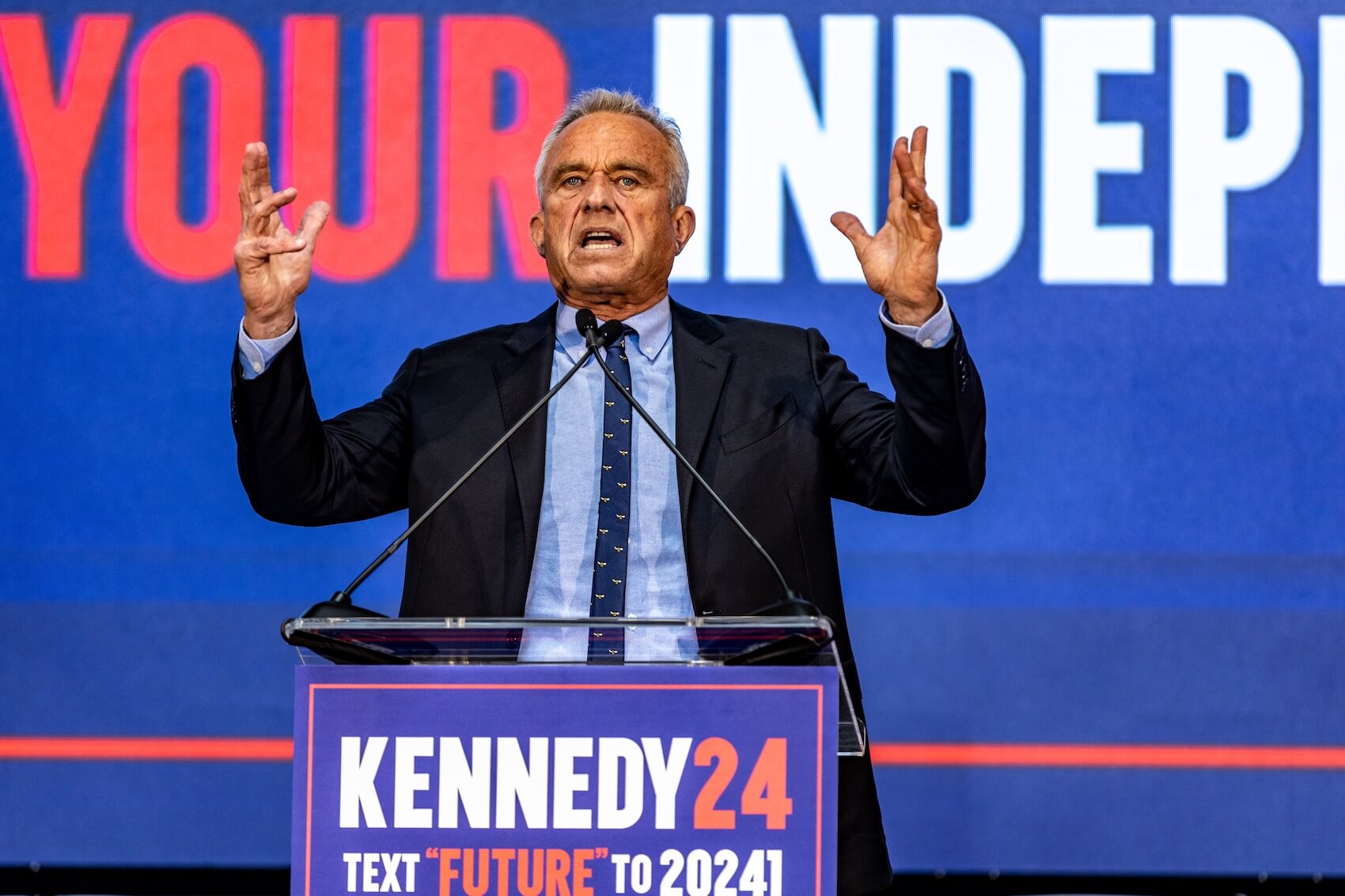

Regarding the disproportionate focus on post-material issues, the implications are far-reaching. This emphasis on post-material causes means that critical problems in the US, such as income inequality, homelessness, underemployment, poverty, and inadequate access to healthcare, are not prioritized in political discourse. To be a liberal in the 1930s meant focusing on the day-to-day economic interests of ordinary people. Today, however, left-leaning Silicon Valley elites often concentrate on issues like abortion, DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) programs, LGBTQ rights, and global warming. While these issues are undeniably important, this shift has left economic concerns largely to right-wing populists like Donald Trump.

Although Trump does not approach these issues with serious policy solutions, he, at least, acknowledges them, which resonates with voters. The center-left’s overwhelming focus on post-material issues has been disastrous for the working class and has, in part, enabled the rise of Trump and other MAGA Republicans.

Regarding current political tendencies, there’s no question that some high-profile tech figures—Elon Musk being a prime example—have aligned themselves with Trump and the right. Others, such as Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos, appear to have softened their rhetoric toward Trump, even if they may not have supported him outright. However, voting and campaign finance records suggest that Silicon Valley employees, including both rank-and-file workers and many executives, remain largely Democratic and liberal-leaning.

I think that some high-profile names have definitely turned toward Trump. However, I don’t believe they have changed that much. It’s politics that has changed significantly. For example, even though many Silicon Valley employees—particularly the rank-and-file employees—haven’t changed much in their political tendencies, they are certainly more silent than they were 8 or 10 years ago.

I think some of the rhetoric coming from the tech titans—the entrepreneurs, owners, and founders—stems from sheer pragmatism. They understand Trump as a political reality, and this time, they want to position themselves favorably. As for employees, they see how the world has changed and likely feel there’s little reason to engage in protests, as it probably wouldn’t make a significant difference. Additionally, such actions could potentially get them into trouble at work. So, that was a bit of a rambling answer, but that’s my perspective.

People Believe Social Media Companies Wield Too Much Political Power

Given the discussion on the erosion of public trust in tech firms due to scandals like Cambridge Analytica, what role do you think transparency and ethical considerations should play in maintaining the political capital of these companies?

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: I think it’s quite interesting. Given how much influence tech companies wield and how closely Donald Trump has aligned himself with Elon Musk, public opinion polls in this country clearly show that the vast majority of Americans are skeptical or even negative about tech companies. For example, in my lobbying class, I reference a Pew study from earlier this year that revealed 78% of Americans believe social media companies wield too much political power. To me, this is an astonishing figure.

Despite this widespread skepticism, these companies haven’t yet paid a significant political or economic price. However, I believe this may be starting to change, potentially influenced by recent political shifts among some tech leaders. What do I mean by this? Over the past couple of years, somewhat quietly, multiple states in the US have passed age verification laws for pornographic websites. While this development hasn’t garnered much media attention, I suspect social media companies are paying close attention. They may be wondering if similar regulations could soon target them, particularly given the growing discourse about the harmful effects of social media on children.

For instance, Jonathan Haidt’s highly successful book The Anxious Generation discusses these negative effects, particularly on children, and I think this conversation is beginning to permeate our political discourse. As a result, tech companies will likely need to start addressing the ethical considerations you mentioned. This growing dialogue and the precedent set by regulations on other industries might push tech companies to pay more attention to these issues in the near future.

And lastly, Professor Nownes, there are those pundits arguing that American democracy may not survive another Trump administration. How do you think American institutions will react to a second Trump administration?

Professor Anthony J. Nownes: Well, this is a tough question. For both professional and personal reasons, I’ll say this: Do I think American democracy will survive? Yes, I do. But what it will look like a few years from now? I honestly don’t know. I see some disturbing signs, particularly regarding democratic norms. Many of these norms have taken quite a hit over the last few years. The legal system, for example, has been quite slow in addressing certain actions, especially attempts by the president-elect to change the outcome of the last election. I think this remains an open question. I wish I had a more definitive answer, but at this point, I just don’t know.