Underscoring that Austria represents a unique case where neoliberalism has been driven by far-right politics—a phenomenon not commonly seen in other European contexts—Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider reflects on the FPÖ’s historical trajectory. She explains how the party, initially founded by former National Socialists, positioned itself as a pro-business, liberal alternative to the dominant Socialist and Conservative parties. This liberal economic stance was integrated into government policies when the FPÖ gained power, particularly during its coalition government in the early 2000s, introducing neoliberal measures such as deregulation and market liberalization. “What we’ve seen in Austria,” Professor Ausserladscheider notes, “is an unprecedented case of a far-right populist party significantly influencing economic policymaking.”

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

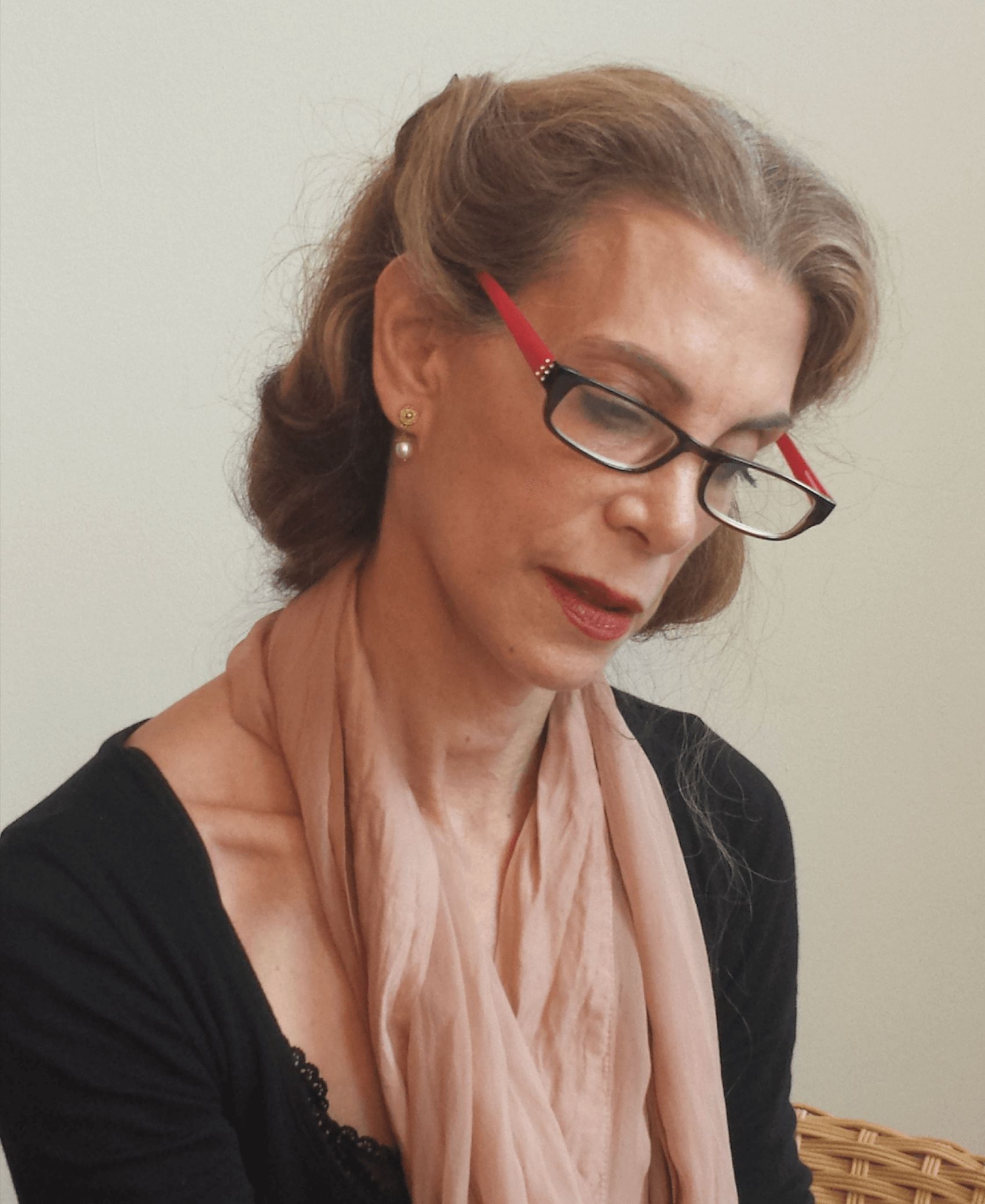

In an engaging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Valentina Ausserladscheider, Assistant Professor at the Department of Economic Sociology, University of Vienna, delves into the complex dynamics of far-right populism and neoliberalism in Austria. She underscores that Austria represents a unique case where neoliberalism has been driven by far-right politics, a phenomenon not commonly seen in other European contexts.

Reflecting on the historical trajectory of the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), Professor Ausserladscheider explains how the party, initially founded by former National Socialists, positioned itself as a pro-business, liberal alternative to the dominant Socialist and Conservative parties. This liberal economic stance was carried into government policies when the FPÖ entered power, especially during its coalition government in the early 2000s, introducing neoliberal policies such as deregulation and market liberalization. “What we’ve seen in Austria,” she notes, “is an unprecedented case of a far-right populist party significantly influencing economic policymaking.”

The professor also addresses the normalization of far-right parties across Europe, emphasizing the shift in the political spectrum, where far-right positions have become increasingly mainstream. She points to recent electoral successes of the FPÖ, mirroring trends seen in Italy, France, and the Netherlands, which indicate a broader European shift that raises concerns about the effectiveness of measures like the cordon sanitaire. “The FPÖ has long been a role model for other far-right populist movements, influencing the political landscape far beyond Austria,” Professor Ausserladscheider states.

Professor Ausserladscheider also highlights the strategic use of economic nationalism and socioeconomic insecurities by far-right parties, which integrates cultural and economic factors to mobilize support effectively. She warns of the dangers of these developments, noting that while far-right populism often challenges liberal democratic values, it simultaneously adopts neoliberal policies, creating what she terms “exclusionary neoliberalism.” This duality, as she explains, is both a tool for political mobilization and a mechanism for reshaping the economic landscape.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider with some edits.

Rise in FPÖ Votes Most Evident in ‘Left-Behind’ Areas

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider, thank you so much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: What role do economic inequality and social marginalization play in the appeal of populist and far-right movements in Austria, and how have these factors been exploited by political parties like the FPÖ?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: I think socioeconomic insecurities and inequalities play a huge role in any kind of party competition and electoral turnout. And, of course, this is also the case for the FPÖ in Austria. Rather than calling it economic inequality and social marginalization, I would frame it under the term socioeconomic insecurities because, very often, it’s a complex set of intertwining factors. Some of these factors might be related to a generally unstable economic situation, which leads to increased perceived insecurities among voters. This means they might be more easily targeted by the FPÖ’s mobilization efforts.

Geography is actually a very good indicator for this. In the recent Austrian elections, we observed a significant gap between people who voted in rural areas versus those who voted in urban places. As some new political science studies suggest, there are “left-behind” places that experience various issues, such as inequality, marginalization, or infrastructural poverty. It’s precisely in these areas that you see a rise in FPÖ votes.

What the FPÖ does is target these specific areas strategically. For example, you’ll see significantly more campaign posters in these areas than in some districts in Vienna because they see a greater chance of mobilizing these electorates. This strategy works well in their favor, and they often suggest that all of these insecurities and economic dissatisfactions are the fault of the centrist parties, political elites, and, very often, migrants. In the FPÖ’s case, this is their key mobilization strategy. The targeting and strategic mobilization are very effective for them, unfortunately.

Connections Between Populism and Business Elites

What is the relationship between populism and business elites in the context of the global rise of populist parties and actors? How do you perceive the relationship between populism and business elites in Austria? Has the rise of populist parties influenced the strategies and behaviors of Austrian businesses?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: The link between populism and business is an important one, and I think we see this particularly well in the US, especially with the way Trump is supported by various business elites. The most recent example is Elon Musk’s very open support for the Trump campaign. We see this kind of support across the board, but I don’t think it’s a straightforward phenomenon. It’s not simply that all businesses are pro-populism. In fact, it’s much more complicated. Some businesses are actively opposed to the far-right and explicitly express that stance.

Here, we observe a clear rift, particularly among businesses interested in international and transnational trade. They are concerned that if far-right populist leaders like Donald Trump come into power and implement trade tariffs, it could create significant problems for their businesses.

In the specific case of Austria, we have seen in the past that there are links between business and the FPÖ. However, as I mentioned, it’s not as pronounced or tangible as in the American context, which is a representative example. But these links do exist. One of the best examples is the recent announcement that Barbara Kolm will be in Parliament for the FPÖ. Barbara Kolm is the leader of the Hayek Institute in Vienna and was previously the president of several important economic organizations in Austria. As such, she is an important figure within the business network. So yes, there are connections.

In your analysis, you mention that right-wing populism can lead to policy decisions that both challenge and benefit business interests. Could you elaborate on how this duality has manifested in Austrian politics, particularly in relation to the FPÖ?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: I think we can go back roughly 20 years, to the second time the FPÖ was in power, from 2000 until 2006. Within that coalition with the Conservatives, the FPÖ implemented many business-friendly regulations and also deregulated some sectors, which were beneficial for businesses. This instance shows a significant internationalization of some market sectors within Austria, partially due to Austria’s entry into the European Union in the late nineties, becoming a member of the common market. However, the FPÖ also pushed for business-friendly policies during this period.

At the same time, when the FPÖ entered the government, it was still a novelty to have far-right populists in power, which is, unfortunately, no longer the case today. This novelty led many European member states to impose barriers on trade cooperation with Austria because they found it unacceptable to engage in bilateral or multilateral agreements with a country led by a far-right populist government.

So, the impact can go both ways. However, times have changed, and we have seen a significant mainstreaming and normalization of far-right actors in power. Therefore, I no longer expect this duality to be as pronounced as it was at the beginning of the 2000s.

Neoliberalism as a Far-Right Project in Austria

How and to what extent does far-right populism impact the nation-specific implementation of neoliberal policymaking? What role do far-right populists play in economic policy change? On this topic what does Austrian experience (FPÖ) tell us?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: I think there are several facets to this, making it quite a complex phenomenon. In economic sociology and political economy, we discuss institutional change—how institutions change, and specifically, how institutions like the state change. The state is a key institution in any political economy. As soon as new governing parties implement different economic policies, you will ultimately see economic policy change. This is not specific to any particular party; it’s inherent to the structure of our liberal democracy.

However, what we have not quite understood until recently, or what has been overlooked, is the power of parties and political forces perceived to be at the margins of the political spectrum—those at the edges. This is no longer entirely true, as we are now witnessing a significant mainstreaming and shift in the political spectrum’s center, which I am happy to discuss further later on.

When the FPÖ came to power in Austria, we saw an unprecedented case of a far-right populist party significantly influencing economic policymaking in a European country. I describe this as neoliberalization. In the early 2000s, partly due to Austria’s entry into the European Union but also because of the FPÖ’s leadership in government, particularly in the Finance Ministry, we saw immense deregulation and the neoliberalization of markets driven by the FPÖ. Until that point, we only understood neoliberalization as a force coming from the center-right rather than the far-right. Austria presents an exceptional case where neoliberalism was a project of far-right politics.

Given your focus on the supply-side of political strategies, how do you see far-right parties in Austria using economic nationalist discourse to frame their policies and mobilize voter support differently than other European countries?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: The way I describe economic nationalism is as a combination of cultural and economic factors that are often tied to economic policies presented as being in the national interest or aligned with national identities. Since nationalism is nation-specific, I would expect that economic nationalism in Italy, for example, would look different from economic nationalism in Austria. It doesn’t necessarily have to be different; similar policies can be described as being in the national interest of any country.

However, because of the national specificity within economic nationalism, it differs in the sense that Austria’s economic nationalism will have its unique characteristics. This is related to what we call methodological nationalism. Of course, we also observe similarities across different cases, such as the resurgence of policy instruments like trade tariffs—long thought to be obsolete in our globalized economy—that are now being implemented again. So, while economic nationalism doesn’t have to differ drastically between nations, discursively, it is distinct as it appeals to the unique national characteristics of each country.

How do you analyze the link between the rise of far-right parties and economic nationalism beyond economic insecurity and cultural backlash?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: One key development, particularly after the great financial crisis of 2008, is that many political economies, especially in cases like Austria, have used economic nationalism as a means to, in a way, rescue neoliberalism. Shortly after the crisis, many countries implemented Keynesian-style demand-side economics, indicating a strong return to demand-side strategies to support economic recovery.

In far-right populist terms, these strategies have often been framed as, or have taken the form of, economic nationalism. Thus, economic nationalism can also be seen as a tool for neoliberal policymaking to maintain stability and persist, even in times of crisis.

Links Between Socioeconomic Insecurities and Cultural Backlash

You argue that the existing literature often separates cultural and economic explanations for far-right support. What methodological approaches would you recommend to better capture the interconnectedness of these factors in studying far-right populism?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: I think one approach is to examine the supply side of political strategies. If you listen to far-right populists and read their programs, you can clearly see that their cultural backlash arguments—such as claims of losing national identity, displacing traditional norms and values, or losing the Austrian way of life—are often tied to economic visions. For example, anti-immigration slogans are frequently justified through economic concerns like resource scarcity or the potential loss of jobs for Austrians. These discursive and rhetorical constructs effectively integrate cultural and economic values as part of their mobilization discourse.

On the other hand, examining the demand side through public opinion studies, such as surveys and electoral polls, can also be insightful. Researchers in this area have shown links between socioeconomic insecurities and sentiments that may relate to cultural backlash. For instance, Noam Gidron and Peter Hall´s study on the politics of social status highlight the economic-cultural linkages in voters’ opinions. These connections become clearer when viewed in relation to one another. However, many supply-side studies still tend to separate these factors. I believe that demonstrating their interconnection can reveal these concurrent effects more effectively.

In your newly published book ‘Far right populism and the making of exclusionary neoliberal state,’ you basically argue that neoliberalism appeared first as a project of the far right. We study populism as the embodiment of illiberal values which at the first glance seems to be contradictory with your assessment. Can you explain how neoliberalism has been a product of far-right populism?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: Neoliberalism has indeed been a product of far-right populism, at least in the case of Austria, although this may not be true across the board. In Austria, you can see quite clearly that after the Second World War, the FPÖ was founded by former National Socialists, who mobilized as a liberal counterweight to the two other core parties at the time: the Conservatives, who were focused on conserving the status quo, and the Socialists, who represented the workers’ interests. The FPÖ sought to provide this liberal counterweight and promoted pro-business policies that the Conservatives were not advocating for. They also supported European integration, which was a novel position in the Austrian political spectrum at that time.

When neoliberalism began to rise in the 1980s, particularly in the US and the UK, it was actually the FPÖ in Austria that adopted these ideas and brought them into government in 1983. For a brief period in that year, they were the junior coalition partner to the Socialists, who had lost their majority after 12 years in power due to the economic impact of the oil crisis. This opened the door for the FPÖ to introduce neoliberal ideas into Austrian politics.

In contrast, in the UK, it was Margaret Thatcher, a Conservative, who championed neoliberalism, and in the US, it was Ronald Reagan, a Republican. So, while these classic conservative forces brought neoliberalism to power in other countries, in Austria, it was the FPÖ.

I think this is the story of Austria that they have adopted these ideas. Yes, it might seem contradictory in the sense that we describe far-right populists as illiberal when they actually promote neoliberal policies. However, when we refer to these forces as illiberal, we mean that they pose a threat to liberal democracy, which is, of course, true. There is evidence of them implementing policies that clearly contradict the foundations of liberal democracies.

What I think we’ve overlooked, though, is that this also includes an economic ideology, and that ideology can indeed be neoliberal. Some authors describe this as “authoritarian neoliberalism,” while I use the term “exclusionary neoliberalism.” You see this specific strain of exclusion when neoliberalism is promoted by far-right populists.

What is the significance of FPÖ’s victory in the parliamentary elections in terms of far-right parties both in Austria and Europe? Do you think ‘cordonne sanitaire’ still holds?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: I think it’s a very important development. For a long time, especially since the 1980s and 1990s, the FPÖ has been a role model for far-right parties across Europe. The leader of the Austrian Freedom Party at the time, Jörg Haider, who took leadership in 1986 and led the FPÖ to significant electoral success in the 1990s, was instrumental in this. We even talked about the “Haiderization” of Europe—a concept referring to this new brand of populism that was adopted by other populist parties beyond Austria.

In many ways, the Austrian Freedom Party has been, and continues to be, a model for far-right populism across Europe. Austria’s recent electoral success mirrors what we’ve seen in Italy, the Netherlands, France, and increasingly in regional elections in Germany. This indicates a broader shift occurring in Europe, which is particularly concerning, especially considering efforts to block these parties have not been very effective.

The Far-Right Becoming Normalized and Mainstream

European Union’s reaction to FPÖ’s victory in 1999 and 2024 are quite different. This time around EU has not reacted to the victory of FPÖ in alarmist terms. Do you think far-right parties have been mainstreamed in Europe in the last couple of years?

Professor Valentina Ausserladscheider: Yes, massively. We’ve seen several things happening simultaneously. To talk about the socioeconomic context, ever since the great financial crisis of 2008, there has been a lot of economic instability across various countries. That instability was further exacerbated by several events, particularly in 2014-2015 when there was a significant influx of migrants, which far-right parties used as a mobilizing tool. Then we had the pandemic, inflation, and now a slight recession. This context has created fertile ground for far-right populists to mobilize.

At the same time, there has been a shift in party competition, with more and more conservative politicians seeking to attract far-right voters. They tried to win votes on far-right issues, but the problem with that strategy is that people tend to choose the original. If voters want a nationalist, exclusionary party, they are likely to go for the FPÖ, AfD, Marine Le Pen, and others like them. This shift in party competition has effectively moved the entire political spectrum to the right, even leading centrist parties to try and mobilize on similar issues, such as immigration, though often unsuccessfully.

This rightward shift in the entire political spectrum has made the far-right appear less extreme. We have seen a huge normalization of far-right powers in government, starting with Austria as a role model, as I mentioned earlier, and then spreading to other countries. We saw Brexit, influenced heavily by Nigel Farage and UKIP; Trump’s presidency in the US; Giorgia Meloni governing in Italy; and three separate instances of the FPÖ governing in Austria.

As a result, the far-right now seems more normalized and mainstream, particularly as countries like Austria are still considered liberal democracies. If we can conceive of a far-right populist government operating within a liberal democracy, it contributes to the perception that these movements are more normal and mainstream.