In this in-depth interview for ECPS, Professor Tim Bale offers a sharp assessment of Reform UK’s rise and Nigel Farage’s polarizing leadership. Farage, he argues, is “a Marmite politician — people either love or hate him,” making him both Reform’s engine and its constraint. Professor Bale suggests that Farage exemplifies “a classic populist radical-right leader” who channels anti-elite sentiment, yet risks alienating voters beyond his base. He links Reform’s surge less to ideological realignment than to Conservative decay, marked by Brexit fragmentation, leadership churn, and “over-promis[ing] and under-deliver[ing] on migration.” While Reform may reshape the political terrain, Professor Bale warns its ceiling remains visible—especially if questions of competence, Russia, and generational change intensify. Reform’s future, he concludes, is possible, but far from inevitable.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

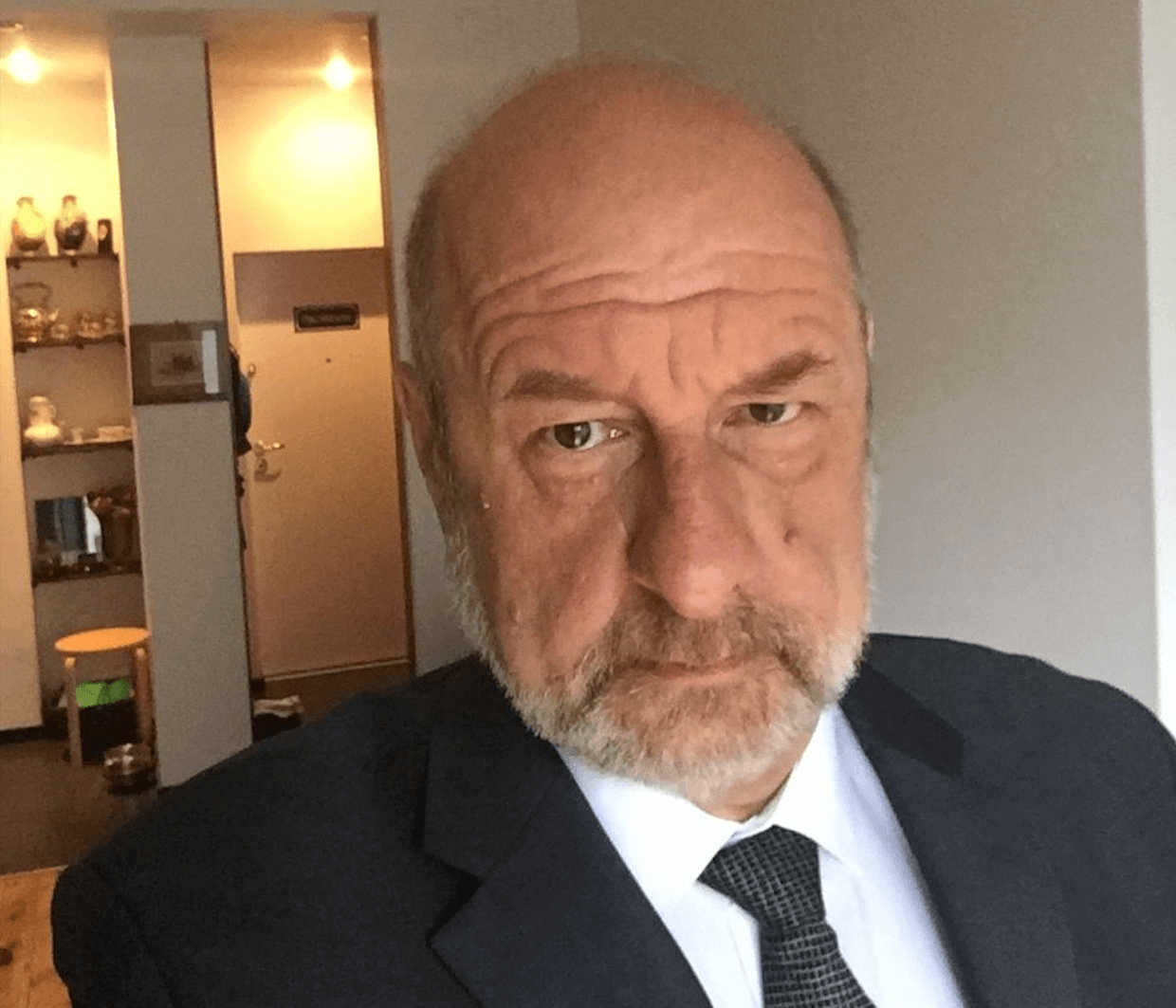

Giving an interview to the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Tim Bale—Professor of Politics in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary University of London—offers a wide-ranging analysis of Nigel Farage, Reform UK, and the structural realignments reshaping British party politics. His insights are grounded in decades of scholarship on party evolution, populist rhetoric, and leadership psychology, making his perspective essential for understanding the United Kingdom’s shifting electoral landscape.

Throughout the interview, Professor Bale situates Nigel Farage as both emblem and engine of Britain’s contemporary radical right. As he puts it, “Nigel Farage is, in many ways, a classic example of a populist radical-right leader,” one who mobilizes support through a moralized confrontation between “the people” and supposed elite betrayal. Yet Farage’s strength is also his constraint. Professor Bale memorably describes him as “a Marmite politician,” a figure voters “either love or hate,” noting that this polarization “probably places a limit on Reform’s appeal.” Farage, therefore, embodies both populist vitality and electoral risk—“the ideal leader” in the eyes of his base, yet “a figure of suspicion” for many beyond it.

This duality frames Professor Bale’s central contention: that Reform UK’s rise must be understood not only in ideological terms but as an artefact of Conservative decay. Years of intra-party conflict, Brexit-driven fragmentation, and “over-promis[ing] and under-deliver[ing] on migration” have opened political space for Farage’s insurgency. Yet Professor Bale cautions against assuming an irreversible realignment. The Conservative Party remains “rooted in the middle-class political culture of the UK,” with institutional depth and internal veto points that make any “reverse takeover” more difficult than populist narratives imply.

Focusing on the structural and sociological conditions that shape political possibility, Professor Bale further highlights a widening generational divide. While education and age have become stronger electoral predictors than class, cultural conflict alone cannot explain support for Reform. If public priorities shift back from national issues to personal ones—from immigration to “the cost of living, [and] the state of public services”—Reform’s momentum may plateau. Moreover, its perceived softness on Russia remains “an Achilles’ heel,” one that stalled its surge when public attention sharpened in 2024.

Across this interview, Professor Bale neither exaggerates inevitability nor discounts volatility. Instead, he offers a sober framework for evaluating whether Reform represents a durable transformation or a protest cycle with a ceiling. Britain, he suggests, now faces a future where polarization, demographic turnover, institutional vulnerability, and charismatic leadership converge—precariously. This conversation, therefore, is not only timely, but analytically consequential.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Tim Bale, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

Farage Is a Classic Populist Radical Right Leader

Professor Tim Bale, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: In your work with Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser on the mainstream right’s strategic squeeze between Inglehart’s “silent revolution” and Ignazi’s “silent counter-revolution,” how should we interpret the rise of Reform UK? To what extent does Nigel Farage embody a classic mobiliser of counter-revolutionary sentiment, and to what extent do the Conservative Party’s specific organizational, ideological, and reputational vulnerabilities make the UK an outlier in the broader pattern of West European party-system transformation?

Professor Tim Bale: I think you would have to say that Nigel Farage is, in many ways, a classic example of a populist radical-right leader. He constantly draws a distinction between the wisdom of “the people” and their alleged betrayal and condescension by elites. As for the Conservative Party, there has always been a strain of populism and nationalism—indeed, some would say jingoism—within its tradition. In recent years, particularly under Boris Johnson and during the Brexit campaign, this tendency has come to the surface. In that sense, the party has reached back into its more populist and nationalist heritage as a way of competing with Farage and the political space he has claimed.

The Tories Are Hard to Capture — But Not Impossible

Farage’s rhetoric about a prospective “reverse takeover” foregrounds questions of party permeability and factional capture. Drawing on your analyses of Conservative factionalism and recurrent leadership crises, what structural, ideological, and organizational conditions render the Conservative Party susceptible to colonization by a radical-right challenger? Conversely, what features of party culture, elite networks, or institutional veto points might inhibit such a takeover?

Professor Tim Bale: When you look at the Conservative Party, there are features that, while not necessarily inoculating it from the challenge Farage poses, do make such a takeover more difficult than some people imagine, in the sense that it is a party rooted in the middle-class political culture of the UK. It is a party that has existed for 200 years, and it has a strong sense of entitlement, as it were, and a strong belief that it is the natural party of government, and therefore will be able to resist, in some ways, any challenge from a newcomer.

Having said that, however, one feature of the Conservative Party that always has to be borne in mind is that it is very strongly a leadership-driven party, and that should a leader take over who is more receptive to the kinds of overtures that Nigel Farage and others are making, then it would be quite easy for that person to convert the party to taking a much more hospitable attitude to that development. So, on the one hand, the fact that the Conservative Party is old, has a brand, and has an infrastructure makes it quite difficult for somebody to take it over. On the other hand, it can be taken over quite easily from within, because it is so reliant on the leader to show it the way in terms of policy and organization.

Farage Is Reform’s Greatest Asset and Its Weakest Link

Your recent interview on Reform UK emphasizes Farage’s dual status as both the party’s central mobilizing force and its principal liability. How does this tension map onto broader theories of charismatic leadership, affective polarization, and “anti-system” appeal? In an increasingly fragmented multi-party context, does Farage’s polarizing image constrain the party’s governability narrative to the point of limiting its credible path to No. 10?

Professor Tim Bale: Nigel Farage is what we call, in England, a Marmite politician, which refers to a yeast-based spread that people put on their toast in the morning. People either love or hate that particular spread, and that’s very true of people’s attitudes to Nigel Farage. I think the fact that he is such a polarizing figure probably places a limit on Reform’s appeal. At the moment, it seems to be polling around 30% in the opinion polls, and I think that reflects the fact that he finds it difficult to appeal to voters who hate him, obviously, but also that ambivalent voters may be wary of the polarization he represents. So, I do think that is something of an obstacle to Farage’s progress. The anti-system appeal you mention is clearly attractive to some voters — people fed up with the two mainstream parties who want to smash the system. Anyone like Nigel Farage, who seems to offer a more radical alternative, is an appealing option for them. However, there is still a strong streak of small-c conservatism in the British electorate that would regard that as too radical, and that would like change — but not at the cost of dismantling a parliamentary, liberal, representative democracy that, in many ways, has served Britain well over the last couple of hundred years.

Reform’s Rise Is Built on Tory Collapse as Much as Ideology

Your research on Conservative leadership instability highlights the compounding effects of leader unpopularity, policy incoherence, and internal disunity on electoral performance. How much of Reform UK’s current momentum should be understood through the lens of “opportunity structures” created by Conservative decay, rather than any substantive ideological realignment toward radical-right policy demand?

Professor Tim Bale: As always, what we’re seeing is a combination of both. I mean, there is some genuine appeal of Reform UK’s policies and pitch to the electorate. But obviously, what has gone wrong with the Conservative Party has opened up avenues for Reform in a way that we haven’t seen before. In particular, the fact that the Conservative Party has really, since 2010, over-promised and under-delivered on migration has made it much easier for Farage to suggest that somehow it has failed voters and that it has not been able to, as it were, live up to their expectations.

Also, you would have to say that the way the Conservative Party has lost its organizational coherence, the way Brexit, for example, tore the party apart and made parliamentary discipline something of a fiction, hasn’t helped—nor has the party’s tendency to cycle through leaders so quickly. That has led to a feeling that the Conservative Party, oncea sort of solid, respectable governing party, has to some extent lost its way, even lost its mind, according to some voters. And I don’t think that has helped the Conservative Party, but I do think that’s helped Nigel Farage and Reform UK.

Many Tory MPs Would Be Comfortable in a PRR Party

In “Populism as an intra-party phenomenon,” you analyzed how Corbynism reconfigured Labour’s organizational dynamics and membership incentives. Do you observe analogous intra-party populist dynamics emerging within the Conservatives today—particularly in the struggle between traditional conservatives, post-liberal cultural conservatives, and those advocating rapprochement or fusion with Reform UK?

Professor Tim Bale: There are definitely, if not factions, then certainly groups within the Conservative Party who are battling it out for the party’s soul. You can see that there is very clearly a bunch of MPs who, if not wanting a merger with Reform UK, would actually be quite open to the idea of some kind of electoral pact with Farage’s party. I think that partly is instrumental opportunism on their part, in the sense that they think the Conservative Party is in trouble, and it needs an alliance of some kind with Reform UK to recover its fortunes.

But, there are MPs within the Conservative Party who, to be honest, would be quite comfortable belonging to a populist radical right party. They believe that Britain needs shaking up economically, and that the only way for that to happen is actually to get a greater level of support from the electorate, based on cultural concerns—concerns around immigration, woke issues, and green policies. That’s the only way of getting the kind of government that they want to actually dismantle some of the welfare state and some of the regulation that they think is holding Britain back. So, you have a strange situation in the Conservative Party where there are many advocates of a much more neoliberal conservatism who are prepared to adopt a more authoritarian stance on cultural concerns in order to get into government and implement the kinds of economic policies that they think are absolutely vital.

The Tories Are Now Moving on Migration in Farage’s Direction

Your comparative work on UKIP/Brexit Party and Australia’s One Nation highlights how radical-right “outsiders” can generate policy payoffs without executive power by reshaping the strategic environment of mainstream parties. How is Reform UK already influencing Conservative rhetoric, agenda-setting, and internal factional alignments—especially on immigration, welfare, and ECHR withdrawal?

Professor Tim Bale: You put your finger on a phenomenon that occurs throughout the world, and we’ve seen it all over Western Europe, when parties with little hope of actually governing—and certainly of joining a coalition—are capable of, as it were, moving the center of gravity in a system towards the populist radical right. When you look at the Conservative Party’s policy-making since 2024, and even actually before that, in response to the threat that Nigel Farage’s various parties—be it UKIP, be it the Brexit Party, be it Reform UK—you can clearly see that the Conservative Party has moved very much in his direction.

So, on migration, we now have a Conservative Party that has suggested—though there is some debate over whether it was intended seriously—withdrawing the indefinite right to remain granted to some non-citizens, and even opening up the possibility of them eventually being encouraged or indeed deported. That kind of mass-deportation approach is something previous Conservative governments would never have considered, and it reflects a direct response to some of Nigel Farage’s arguments.

Welfare is more complex. Farage is very aware that many of his supporters rely on the welfare state, and certainly on the National Health Service, so the Conservative Party must be cautious not to move too far toward his ambivalence on those issues. Instead, it tends to fall back on its more familiar low-tax, low-spend reputation.

On migration, that is the obvious one, where we’ve seen the Conservative Party move, just as we’ve seen parties, whether they be Christian Democrat or Conservatives across the continent, move very much towards a rather more kind of radical policy. You’d also have to look at environmental politics here, and it’s very clear that over the last few years, a Conservative Party that actually pioneered the move towards net zero—when Theresa May was Conservative Party Premier—is now really talking about winding back that commitment. I think, again, that is in response to Nigel Farage and Reform, and their promotion of the fossil fuel industry and its arguments.

Local Failures Might Not Dent Reform as Much as Opponents Hope

Reports of dysfunction in Reform-run local authorities raise questions about statecraft and institutional capacity. Given your longstanding argument that perceived competence ultimately constrains populist breakthroughs in Britain, do you anticipate that these governance shortcomings will erode Reform’s credibility? Or, alternatively, might anti-establishment narratives inoculate the party from such accountability?

Professor Tim Bale: That is a great question. We have seen Reform take over local authorities since spring of this year, and many of those councils have made rather a mess of things. They’ve fallen out with each other, they’ve found it much harder to make savings than they originally suggested, and in fact, they’re going to have to raise taxes rather than reduce them for local people. While the problems in those local authorities actually gain quite a lot of amused coverage in the media, I’m not sure how much the electorate in general pay attention to them if they’re not happening in their particular part of the country.

You raise a very good question here about the extent to which, if you criticize Reform UK, you actually strengthen, in some ways, the support for it among its die-hard advocates and voters. So, one would like to think that the example of local councils actually gives people pause for thought about whether it would be a good idea to elect Reform to the government of the country as a whole. But I rather doubt that it will have as big an impact as some of Reform’s opponents hope.

Hardline Accommodation Risks Alienating Supporters While Boosting the Radical Right

Your scholarship has shown that center-right parties often pre-empt or accommodate radical-right positions under competitive pressure. Should we expect Labour or the Conservatives to adapt their stances on immigration, welfare conditionality, or international legal obligations in response to Reform’s pressure? What do cross-national patterns suggest about the risks and limits of such accommodation?

Professor Tim Bale: We are already seeing in the UK the Labour government take a much harder line on migration than many of its supporters would like. It’s clear that that is a response by the government to losing votes to Reform. Current polling suggests that around 10% of people who voted for Labour in 2024 are now intending to vote for Reform, and Labour is desperate to get some of those people back, and by pursuing a more authoritarian stance on migration, they hope to do that.

You also point, however, to the fact that this has gone on all over the European continent. We’ve seen center-left parties as well as center-right parties pursuing a harder line on migration, and Denmark is often the country pointed to in this respect, perhaps as a successful example. But when we look across the continent as a whole, we don’t find that it is a particularly useful response for center-left parties to take. It ends up doing two things: first, alienating many of their more obvious supporters—in other words, people who have more liberal or left-wing values; and second, it tends to prove counterproductive or futile, in the sense that all it does is raise the salience of issues like migration in the minds of most voters, causing elections to be fought and debate to be conducted on terrain that actually favors populist radical right parties.

So, I personally wouldn’t advocate that as a response by the center-left, but it’s one that is still often mooted and taken by center-left parties, unfortunately.

Farage’s Sympathy for Putin Is an Achilles’ Heel

Your work on leadership perception underscores how trait attributions shape political choice. How electorally damaging is the perception that Reform UK is “soft on Russia,” particularly given polling indicating its unusually high association with pro-Russia sentiment? Does this reputational liability limit its potential to broaden its coalition beyond anti-establishment voters?

Professor Tim Bale: Reform’s support, Reform’s support, and certainly Farage’s apparent sympathy for Putin’s justification of the invasion of Ukraine, is something of an Achilles’ heel for him. To be clear, Farage has been careful not to appear as a superfan of Vladimir Putin, but he has repeatedly suggested that Russia’s invasion has been influenced by NATO “poking the Russian bear” and extending its influence into Ukraine in ways that allegedly threatened Moscow.

Polling from the 2024 election shows that the moment public attention focused on Farage’s more accommodating stance toward Putin and Russia, Reform’s upward trajectory stalled. This position is deeply unpopular in Britain, and it is something Farage will have to address seriously, especially ahead of the next election. After all, the country will be choosing a government and prime minister in a highly unstable geopolitical moment, and Russia is viewed by the overwhelming majority of Britons as the aggressor.

So, I think it is a limit to his appeal unless he begins to resile from it. At the moment, however, it doesn’t look as if he wants to do that. I should add a caveat here: when we look at other populist radical-right parties, and indeed more extreme variants of the radical right in Europe, there does not appear to be anything like the same level of enthusiasm for Russia and for Putin within Reform as we see in some of their continental counterparts.

Reform Voters Favor Leaders with ‘Dark Triad’ Traits

Your “What Britons Want in a Political Leader” study reveals stark divergences between the traits valued by Reform/Conservative members and those preferred by the broader electorate. What does this asymmetry imply about Reform’s sociological and psychological ceiling of support, and what does it reveal about the electorate segments most susceptible to Farage’s appeal?

Professor Tim Bale: What we find in our research is that supporters—and certainly members of Reform—have much more positive views about leaders who exhibit what psychologists would call dark triad qualities. In other words, those are Machiavellianism, for example, psychopathy, for example. That is a marked contrast with the supporters of other parties, although slightly less so with supporters of the Conservative Party, who are rather more like Reform.

I think this comes down, once again, to Nigel Farage’s appeal. For his supporters, he is, in some ways, the ideal leader: he exhibits the kind of ruthless and sometimes manipulative, clever qualities that they so admire. But those very same qualities are actually quite off-putting to a large segment of the British electorate. So once again, if we’re talking about limits to Nigel Farage’s appeal, the kind of leadership qualities that he has—the leadership that he demonstrates—make him intensely popular with his own supporters, because they are psychologically predisposed to like that kind of leadership. Whereas for many in the electorate, they make him a figure of suspicion rather than someone they would like to see leading the country.

The Greens, Not Corbyn, Pose the Greater Danger to Labour

Reform appears to be peeling off older, culturally conservative, economically insecure voters, while recently founded socialist Your Party seems poised to attract younger, urban, progressive activists disillusioned with Labour. How vulnerable is Labour to a “two-front erosion,” and do Starmer’s strategic concessions on immigration and public order risk replicating the center-left dilemmas seen elsewhere in Europe?

Professor Tim Bale: You’ve seen recently Your Party try to get its act together. This is the party being set up by, among others, Jeremy Corbyn, who used to be the very left-wing leader of the Labour Party, and Zara Sultana, an ex-Labour MP. There is an extent to which this does threaten Labour’s hegemony on the left. There are many left-wing voters who are very disappointed with the Labour government, not least on its attitude to migration, but also on its attitude to tax and spend.

What I would say, however, is that I’m not sure Your Party is actually the biggest threat to Labour on that front. I think what we’ve seen recently is that the difficulties that Your Party have had in actually getting its act together, as I said before, mean that the Green Party has seized the moment. It’s elected a new so-called eco-populist leader, Zach Polanski, who appears to be saying and doing the kinds of things that people disillusioned with Labour would actually like—so, for example, wealth taxes, and a much more aggressive attitude to Nigel Farage and Reform UK.

So, if there is a kind of two-front war being fought by Labour—Reform on the one hand, and then a left-wing party on the other—it’s probably not Your Party; it’s probably the Greens that are the biggest threat on its left flank.

First-Past-the-Post May Save Labour

Drawing on your prior analyses of organizational dysfunction within left-of-center parties, how serious a threat is Your Party’s emergence—given its early factional disputes and resource constraints—to Labour’s ability to consolidate progressive voters? Might it institutionalize a structural cleavage on the British left akin to Podemos–PSOE or Mélenchon–Socialist Party dynamics?

Professor Tim Bale: There is a risk. There We talked about some of the problems that Your Party have had. There is a risk that if they can actually surmount some of the early difficulties that they have, then we do see a party on the left—whether it be Your Party or the Greens—actually draining support from Labour. Current opinion polling does suggest that around 10–15% of former Labour voters have drifted off and might drift off in that direction.

However, there’s always the constraining factor of our electoral system. It is always going to be possible for Labour, successfully or unsuccessfully, to argue that under a first-past-the-post system a vote for either the Greens or Your Party is a wasted vote, particularly if they are able to conjure up the possibility of a Reform government under Nigel Farage, which may frighten sufficient numbers of people who might otherwise be tempted to use their vote expressively and to vote for Your Party or the Greens. They may wonder whether that is a good idea and, actually, in the end, come back home to the Labour Party. Probably that is the Labour Party’s strategy at the moment.

Conservatives Misread 2019 as Permanent Shift, Ignoring Voters’ Economic Priorities

In “Hopes Will Be Dashed,” you argued that Brexit negotiating strategies were deeply shaped by a pervasive “Merkel myth.” Do you see contemporary Conservative or Reform elites relying on analogous political myths—such as a presumed majority demand for “uniting the right,” a belief in the inevitability of populist realignment, or a misreading of public appetite for hard-liner sovereignty politics?

Professor Tim Bale: That is a great question. I think one of the problems that the Conservative Party in particular had was a misreading of the 2019 election result as proof of what they called the realignment. In other words, the sense that working-class voters in this country had moved very much to the right on social questions, on cultural questions, and therefore there was some kind of permanent change of which the Conservative Party would be the beneficiary—when in fact that election was, in some ways, a rather more contingent affair, influenced very much by Brexit, influenced very much by the personality of Jeremy Corbyn, and indeed, Boris Johnson.

That myth—the idea that somehow there has been this incredibly profound change, and that cultural politics is now the dominant factor in elections—is still something that the Conservative Party holds onto, much to its detriment. It’s very interesting when you look at the leadership election in the Conservative Party following the 2024 general election. All the talk was about the Conservatives’ failure on migration, rather than the Conservatives’ failure to provide the country with adequate economic growth and adequate public services.

So, there is a kind of fixation on cultural politics and on this so-called realignment that the Conservative Party still has, which makes it actually quite difficult for it to realize that there is more to life than migration and woke, and indeed net-zero—that, in fact, the British public are not that different in the sense that they still want a government that hopefully provides them with peace, prosperity, and public services that actually work.

Britain Is Slowly Becoming More Liberal

You have frequently noted the role of media ecosystems in amplifying or constraining radical-right actors. To what extent is Reform’s surge a product of media-driven agenda-setting, and to what extent does it reflect deeper structural and sociological realignments within British politics? How should we disentangle these forces analytically?

Professor Tim Bale: That is a great question, but it’s also a very complicated one. Having shed doubt on this idea of a realignment, it is definitely the case that class features much less as a driver of people’s voting in this country, and that, in fact, education and age, to some extent, now seem to be the best predictors of which way people are going to vote. I do think cultural questions have come up in the mix, but I would want to say that the economy—while it’s not the only thing, the only game in town—is still actually very important as a driver of the way that people vote.

If you step back and look at cultural change in this country, clearly there are many voters who are uncomfortable with that, but they tend to be in older generations and, of course, will eventually disappear from the electorate. Now, that’s not to say that the center-left will somehow come into a kind of inevitable inheritance, because younger voters are rather more liberal and more tolerant in their attitudes. But it is to say that the center-right has to be very careful that it doesn’t end up on the wrong side of history, to coin a cliché, and fails to recognize that, for all the turmoil going on in British politics, underneath that, voters are becoming rather more liberal, more tolerant, and—despite media-driven polarization—more comfortable with a multicultural, multi-ethnic Britain.

So how long politics and political parties can thrive by exploiting differences, concerns, and anxieties is an open question.

If Living Costs Top Immigration, Reform Could Stall

And finally, you have cautioned that a Reform-led government is “not inevitable.” What empirical indicators—electoral, organizational, reputational, or demographic—would persuade you that (a) Reform UK is on a trajectory toward executive power, or (b) its rise represents a cyclical protest mobilization likely to dissipate before the next general election?

Professor Tim Bale: You have to look at support for Nigel Farage in particular, and the extent to which people think he will or won’t make a good Prime Minister. In the end, people know that they are voting not just in protest against something but are actually having to elect a government that’s going to make some very important decisions, and Nigel Farage is so central to Reform’s appeal that what people think of him is extremely important.

You also have to look at the extent—and obviously this, to some extent, involves prediction as to which issues are going to be most important for people at the next election. At the moment, immigration seems to be top of the list, but it’s only top of the list when you ask people what is the most important problem facing the country. When you ask people what’s the most important problem facing you and your family, immigration drops down the list, and the cost of living, the state of public services, comes right up.

So, I would probably look at the extent to which that is changing. If people think that migration is making a difference to them and their family, then perhaps that bodes well for Reform. But if the current disjunction between what people think is important to the country and what people think is important to them and their families continues, Reform is less likely to gain in strength.

Then, you’d have to take account of the kind of geopolitical situation, given we’ve already talked about Russia being something of an Achilles’ heel for Reform UK. If you were to see any extension of Russia’s aggression in Europe, then that would make it very difficult for Reform UK to make a convincing case for government.

I’d also look at what’s happening to the Conservative Party to bring it full circle. If the Conservative Party continues to stay in the doldrums—in other words, if it can’t recover itself and it can’t get anywhere near 25–30% of the vote—then there are many people who would normally vote Conservative who might be prepared to vote Reform, and that would give Reform a chance of government.

One final thing to throw into the mix is that our electoral system is not really very well suited to the party system that we now have. We now have a five-party—maybe six, seven, eight-party—system in this country, operating alongside an electoral system that is suited only to two parties, which means that it could be possible that a party on just under 30% of the vote could get a majority in Parliament next time around, and that would be a very unstable situation for the UK.