In his lecture at the ECPS Summer School 2025, Professor John M. Meyer offered a compelling exploration of the relationship between populism and climate politics. He critiqued authoritarian populism as a threat to equitable climate action while also questioning mainstream climate governance’s elitist, technocratic tendencies. Rather than viewing populism solely as an obstacle, Professor Meyer argued that climate justice movements themselves embody a form of inclusive, democratic populism—centered on equity, participation, and solidarity. Drawing on examples from grassroots activism and Naomi Klein’s concept of “eco-populism,” Professor Meyer proposed that climate action must address material injustices and engage people where they are. His lecture encouraged participants to rethink populism as a political form that, when inclusive and justice-oriented, can help build legitimate, durable, and democratic climate solutions.

Reported by ECPS Staff

Climate change intersects with numerous issues, transforming it into more than just an environmental challenge; it has developed into a complex and multifaceted political issue with socio-economic and cultural dimensions. This intersection makes it an appealing topic for populist politicians to exploit in polarizing societies. With the global rise of populist politics, climate change has increasingly become part of populist discourse—whether as a scapegoat for economic grievances, a symbol of globalist overreach, or an arena for nationalist contestation.

Populist politics present additional barriers to equitable climate solutions, often framing global climate initiatives as elitist or detrimental to local autonomy. As a result, populism in recent years has profoundly impacted climate policy worldwide, encompassing a wide spectrum—from the climate skepticism and deregulation of leaders like Donald Trump to the often ambiguous and contradictory stances of left-wing populist movements.

We are convinced that this pressing issue not only requires an in-depth understanding but also demands our combined effort to seek innovative and just solutions. Against this backdrop, the ECPS Academy Summer School on “Populism and Climate Change: Understanding What Is at Stake and Crafting Policy Suggestions for Stakeholders,” held online from 7 to 11 July 2025, aims to critically examine these themes. The program sought to foster a deeper understanding of the tension between economic, political, and environmental interests in populist ideologies, with a particular emphasis on the key conclusions from the Baku Conference on climate justice and populism (2024), which foregrounded the impact of authoritarian and populist politics in shaping global climate governance.

In this context, the second lecture of the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025, titled “Climate Justice and Populism,”represented a major conceptual pivot. It was masterfully moderated by Dr. Manuela Caiani, Associate Professor of Political Science at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Italy, whose own scholarship on right- and left-wing populism, new authoritarianism in Europe, and the politics of emotions provided an ideal framing. Dr. Caiani’s introduction emphasized how populism, climate justice, and ecological transition intersect in her ongoing research projects. She underscored that these issues occupy overlapping analytical terrains and encouraged participants to re-examine prevailing assumptions about the relationship between populism and environmental politics.

The lecture was delivered by Dr. John M. Meyer, Professor in the Departments of Politics and Environmental Studies at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt. Professor Meyer’s work as a political theorist seeks to illuminate how social and political values and institutions shape—and are shaped by—our relationship to the environment. His scholarship includes influential contributions such as Engaging the Everyday: Environmental Social Criticism and the Resonance Dilemma (MIT Press, 2015) and The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Political Theory (Oxford University Press, 2016), both regarded as foundational texts in environmental political theory.

Between 2020 and 2024, Professor Meyer served as editor-in-chief of the prestigious journal Environmental Politics, where he promoted interdisciplinary dialogue on environmental governance, justice, and democracy. In this lecture, Professor Meyer foregrounded theoretical and normative questions over empirical case studies, inviting participants to rethink fundamental assumptions about populism, climate change narratives, and policy frameworks. His intervention challenged the view that populism is inherently an obstacle to climate action, instead offering a nuanced analysis of how climate justice movements themselves may embody a form of progressive, democratic populism.

This lecture not only set an intellectual benchmark for the ECPS Summer School but also provided a critical lens through which to engage with the central themes of populism and climate governance for the remainder of the program.

Structure of the Lecture

Professor Meyer organized his presentation into three interrelated thematic strands:

- Authoritarian Populism as a Threat to Climate Justice

- Mainstream Climate Action as Anti‑Populist

- Climate Justice as a Manifestation of Inclusive Populism

These three themes, Professor Meyer argued, should be understood sequentially and relationally, with each offering a reframing of the politics of climate change in contemporary democracies.

Authoritarian Populism as a Threat

In the opening analytical section of his lecture, Professor Meyer turned his attention to what he termed authoritarian populism as a threat to climate policy and action. Speaking from a conceptual standpoint, Professor Meyer carefully clarified that while he sought to illuminate the ways in which authoritarian populism undermines climate governance, he did not intend to suggest that populism itself is the core problem. Rather, he argued, authoritarian populism should be understood as a significant manifestation of a broader political challenge to climate justice, while populism as a mode of politics might also contain emancipatory potential.

Professor Meyer outlined key characteristics of this authoritarian populist threat, situating it primarily among right-wing and, in some cases, explicitly fascistic parties and leaders. These actors, he observed, routinely frame climate policy as an elite-driven and globalist project, leveraging this framing to claim that they are defending “the people” against perceived external impositions. Yet, Professor Meyer noted that the conception of “the people” advanced by authoritarian populists is deeply homogenizing—constructed in a way that deliberately excludes as many as it purports to represent, marginalizing pluralism and dissent.

An important distinction Professor Meyer drew was between authoritarian populists’ selective embrace of environmental concerns: many such actors profess to defend local or national environments—protecting land, waterways, or rural communities within their conception of the “homeland”—while simultaneously attacking global climate change mitigation efforts. This selective environmentalism serves to bolster nationalist narratives while rejecting multilateral climate agreements and policies.

Professor Meyer further emphasized that authoritarian populist parties and movements often deny or express skepticism about the very existence, causes, or urgency of climate change. This skepticism politicizes climate change itself, framing it as a contested, ideologically loaded topic rather than a shared global challenge grounded in scientific consensus.

While acknowledging these dangers, Professor Meyer stressed that authoritarian populism’s climate denialism and obstructionism should be understood in context—not as an indictment of all populist politics, but as one specific configuration that climate justice advocates must confront. This framing set the stage for his subsequent analysis of mainstream climate policy and the potential for democratic populist alternatives.

Mainstream Climate Action as Anti‑Populist

In this significant portion of his lecture, Professor Meyer offered a penetrating critique of what he characterized as the mainstream climate action framework, which he argued functions as a form of anti-populism. Beginning with an overview of the institutional landscape—anchored by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its annual Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings— Professor Meyer drew attention to the global policy architecture and its regional manifestations, notably the European Green Deal and the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Professor Meyer suggested that this mainstream approach, despite institutional diversity, shares a common political imaginary steeped in technocratic elitism. It is dominated by establishment actors—mainstream parties, legacy media, global NGOs—who are routinely cast as “elites” in populist discourse. He suggested that this framework is shaped by a nostalgic vision of politics, one that emphasizes civility, pluralism, respect for scientific expertise, and globalist ethics, typified by UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ oft-cited appeal that “we are all in this together.” While these values have guided international climate discourse, Professor Meyer argued that they also drive a political culture that instinctively rejects populist critiques as dangerous politicization.

This elitist imaginary, Professor Meyer contended, is reflected in the dominant policy instruments. For over three decades, mainstream climate policy has revolved around carbon pricing mechanisms, including cap-and-trade schemes and carbon taxes. More recently, policies such as the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the European Green Deal have moved toward industrial policy approaches centered on state incentives and partnerships with private industries to foster green innovation. Yet Professor Meyer highlighted a key limitation: the political invisibility of these policies. The IRA, for instance, delivered substantial subsidies and jobs to economically disadvantaged, Republican-leaning regions in the US, yet beneficiaries were largely unaware of the policy’s role due to its technocratic and opaque design. This invisibility, Professor Meyer suggested, made these reforms politically vulnerable to rollback efforts such as Donald Trump’s successful campaign to dismantle key elements of the IRA.

Turning to the discursive landscape, Professor Meyer cited recent commentary—including from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change—which emphasized that mainstream actors must reclaim climate debate from “campaigners” and instead promote pragmatic, outcome-driven solutions. Tony Blair’s framing, Professor Meyer noted, epitomizes an explicit anti-populist stance, doubling down on elite-driven governance while treating public skepticism and populist critique as obstacles to be neutralized rather than symptoms to be understood. Similarly, scholars like Eduardo Campanella and Robert Lawrence, while encouraging better climate storytelling, advocated narratives rooted in entrepreneurial genius and open trade—further exemplifying the technocratic ethos of the mainstream.

Professor Meyer argued that this anti-populist orientation constitutes a political trap. Rather than defusing populist critique, it reinforces the binary at the heart of populist discourse: a moral division between elites and “the people.” By implicitly casting technocratic expertise as virtuous and popular sentiment as irrational, mainstream climate governance aligns itself with elite politics and alienates the very publics whose support it requires. Citing Jonathan White’s distinction between a politics of necessity and a politics of volition, Professor Meyer noted that mainstream discourse tends to present climate action as an imperative dictated by science—a domain where policy options are viewed as objectively correct and public deliberation as an impediment.

However, this technocratic framing, Professor Meyer observed, fails on two critical fronts. First, it overlooks the deep injustices inherent in both the causes and impacts of climate change. Marginalized and impoverished communities—whether in the Global South or within advanced economies—bear the brunt of climate harms despite having contributed the least to global emissions. Second, mainstream climate policy often exacerbates these injustices, imposing disproportionate burdens on precisely those least equipped to bear them while offering inadequate mechanisms for redress or participation.

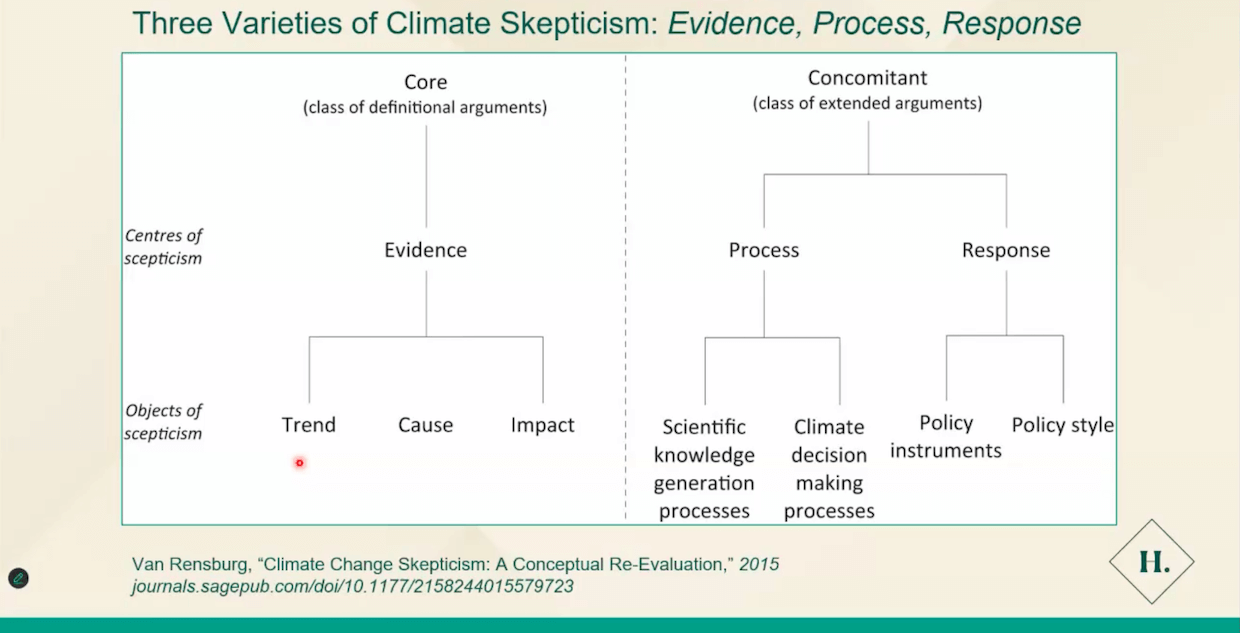

Professor Meyer further noted that this anti-populist imaginary tends to misconstrue populism itself as inherently exclusionary, skeptical of climate science, and therefore an existential threat to climate action. While authoritarian populists often engage in climate denialism and evidence skepticism—ranging from rejection of warming trends to downplaying human causation and impacts— Professor Meyer emphasized that skepticism can take other forms as well. Drawing on von Rensburg’s typology, he distinguished between evidence skepticism and process skepticism. Notably, while many climate justice movements accept the scientific consensus on climate change, they remain deeply critical of the processes by which climate knowledge is produced, who gets included or excluded in decision-making, and the equity of proposed policy responses.

Professor Meyer observed that some right-wing populist movements in Europe and North America have increasingly adopted critiques of climate policy process and response—not to advance climate justice but as part of their broader assault on liberal governance. This convergence of critique from vastly different ideological poles underscores the complexity of the political terrain.

Ultimately, Professor Meyer’s analysis warned that mainstream climate policy’s anti-populist reflex may undermine its own legitimacy by failing to engage with these deeper political, social, and ethical concerns. Instead of depoliticizing climate action, Professor Meyer suggested that a more inclusive, participatory approach attentive to justice and popular grievances is essential for achieving both legitimacy and effectiveness in climate governance.

Climate Justice as Inclusive Populism

In the final—and most innovative—section of his lecture, Professor Meyer turned his attention to a theme that he framed as pivotal to rethinking climate politics: climate justice as a manifestation of populism. This focus represented both a conceptual intervention and an effort to challenge dominant narratives that either marginalize or misunderstand climate justice movements. Professor Meyer argued that climate justice movements represent an alternative, democratic populism. If populism is understood simply as a political form that pits “the people” against “the elites,” then climate justice activists, indigenous movements, and youth-led campaigns embody a progressive populism rooted in solidarity, justice, and inclusivity.

Professor Meyer began by clarifying a key distinction: climate justice movements should not be conflated with climate policy writ large, nor should they be treated as an add-on or afterthought to conventional policy mechanisms. He warned that policymakers often make the mistake of assuming that technocratic tools—such as carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems—can be implemented first, and then some portion of the resulting revenues can be redistributed to marginalized communities to compensate for inequitable impacts. This “compensatory” logic, Professor Meyer emphasized, misreads what climate justice movements themselves seek to achieve. Rather than viewing justice as a supplemental objective, climate justice movements embed questions of equity, inclusion, and systemic critique at the very core of their agenda.

Professor Meyer identified five defining features of climate justice movements that, in his view, mark them as distinctively populist. First was their inclusive conception of “the people.” Unlike the exclusionary and homogenizing populist rhetoric characteristic of many authoritarian right-wing movements, climate justice movements articulate a broad, pluralistic vision of “the people.” This vision centers on those most directly affected by environmental harms: marginalized communities in both the Global South and Global North, Indigenous populations, youth activists, and other groups on the frontline of ecological disruption. Drawing on examples such as the Climate Justice Now coalition in Brazil—organizing a “People’s Summit” ahead of COP30—Professor Meyer illustrated how this inclusive populist imaginary juxtaposes “the people” against polluters, corporations, and political elites.

A second core feature is the rejection of “false solutions.” Professor Meyer noted that climate justice activists frequently deploy this language to critique policies that may appear progressive but fail to address root causes or distribute benefits equitably. He referenced prominent critiques from activist networks and figures like Greta Thunberg, whose characterization of empty climate promises as mere “blah blah blah” captured the impatience of youth-led movements with elite foot-dragging and performative commitments.

The third characteristic Professor Meyer discussed was a distinctive understanding of expertise. Climate justice movements elevate Indigenous, local, and community-based knowledge systems, particularly in the realm of climate adaptation. Professor Meyer stressed that this should not be misunderstood as a wholesale rejection of scientific knowledge but rather as a critique of how dominant climate science and policymaking processes have historically marginalized or ignored situated expertise. By foregrounding these alternative epistemologies, climate justice actors contest the monopoly of elites over what counts as legitimate knowledge and authority.

The fourth feature is a commitment to meeting people “where they are,” recognizing and engaging with their immediate material conditions and everyday struggles. Rather than demanding that communities subordinate their pressing concerns to abstract climate imperatives, climate justice movements insist that effective and just climate action must be grounded in, and responsive to, those lived realities.

Finally, Professor Meyer highlighted the movements’ investment in building cooperative and institutional structures that can sustain long-term commitments to justice and equity. This organizational orientation reflects an ambition to institutionalize solidarity and embed democratic accountability into the very fabric of climate governance.

Throughout this section of his lecture, Professor Meyer implicitly challenged prevailing academic frameworks that define populism narrowly as a phenomenon of electoral politics or demagoguery. Referencing scholars such as Nadia Urbinati, who tend to disregard social movements as “not unusual” and therefore outside the purview of populism studies, Professor Meyer argued that climate justice movements reveal a more complex, inclusive, and potentially emancipatory form of populist politics—one that foregrounds horizontal solidarity, material justice, and epistemic pluralism. In sum, Professor Meyer’s analysis offered a powerful reconceptualization of climate justice not as a peripheral adjunct to mainstream climate action but as an alternative paradigm rooted in participatory populism, critical of elite-driven processes, and attentive to social and environmental equity at every level.

‘Fascist Flip’ in Post‑Disaster Communities

In the final section of his lecture, Professor John Meyer turned to what he identified as a crucial focus of climate justice movements: engaging people where they are now and constructing durable, cooperative structures to sustain solidarity over time. To illustrate this principle, Professor Meyer invoked the recent work of Naomi Klein, highlighting her concept of eco-populism as an alternative political approach capable of countering the dynamics that foster exclusion and reactionary backlash.

Professor Meyer drew on Klein’s 2025 lecture titled “Fascism or Eco-Populism: Our Stark Choice,” in which she revisited the tragic aftermath of the 2018 Camp Fire—the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history. The fire had devastated the town of Paradise, destroying more than 18,000 structures and leaving over 30,000 people homeless. Many of these displaced residents sought refuge in nearby Chico, California—a city of approximately 100,000 people—which initially greeted them with warmth and compassion. Early on, Klein reported, there was a collective spirit of welcome, described by some as a “blanket of love and comfort” extended to these climate refugees.

But as Professor Meyer recounted, Chico’s initial solidarity eroded over time. The city’s limited housing stock, strained schools, and overwhelmed social services could not sustainably absorb such a sudden population increase. This material strain gave way to a political backlash: new conservative officials were elected, and crackdowns on homelessness followed. What was especially notable, Professor Meyer emphasized, was that these refugees were neither immigrants from distant countries nor culturally alien populations—they were displaced residents from a neighboring town. Their rejection underscored how even solidarity rooted in geographic proximity can fracture under economic and infrastructural pressure.

Klein, Professor Meyer noted, described this shift as a “fascist flip”—the transformation from empathy to hostility when societies fail to build the material and institutional foundations necessary to sustain care over time. According to Klein, only eco-populism can counteract this dynamic: a politics rooted in universalism, material equity, and the creation of cooperative structures that ensure no group is scapegoated or left behind.

Professor Meyer highlighted Klein’s praise for figures like Zohran Mamdani, a New York City politician who exemplifies this approach. Mamdani, representing a racially diverse and economically marginalized community where many residents paradoxically supported Donald Trump, did not dismiss or condescend to his constituents. Instead, he listened to their material grievances—stories about broken elevators in public housing and perceived inequalities in the treatment of immigrants. Rather than responding by retreating from migrant solidarity, Mamdani concluded that the left must “raise the floor” for everyone, fighting for universal access to housing, transportation, food, and healthcare.

This vision of eco-populism, Professor Meyer observed, embodies a politics of meeting people where they are—politically, economically, and emotionally. It does not ask individuals to overcome their immediate material insecurities in the name of an abstract climate imperative. Instead, it insists that justice-oriented climate action must address those insecurities as an integral part of building an equitable and sustainable future.

For Professor Meyer, this example crystallized the core lesson: without institutions and structures that can translate compassion into durable material support, solidarity remains fleeting. But with such structures, there exists the possibility—though never the guarantee—of sustaining care, fostering democratic participation, and bridging divides that reactionary forces seek to widen.

Professor Meyer closed this section by emphasizing that climate justice as populism offers an alternative political logic to both authoritarian populism and elite technocracy. It politicizes climate action not through denialism or obstruction, but by challenging whose knowledge counts, whose voices are heard, and whose needs are prioritized. It calls for participatory, bottom-up governance that reinforces solidarity and delivers concrete improvements to people’s everyday lives.

Ultimately, Professor Meyer’s analysis invited his audience to rethink not only climate policy but also their understanding of populism itself. In this reimagining, populism need not be defined solely by exclusion, demagoguery, or authoritarianism. Instead, climate justice movements reveal the potential of an inclusive, egalitarian, and democratic populism—one rooted in solidarity, dignity, and sustainability. As Professor Meyer concluded, this vision does not offer easy guarantees but opens up crucial possibilities for the future of both democracy and the planet.

Conclusion: Toward Eco‑Democratic Renewal

Professor Meyer’s lecture, “Climate Justice and Populism,” delivered as part of the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025, provided a profound conceptual intervention into the nexus between populism and climate politics. By critically interrogating both the exclusionary tendencies of authoritarian populism and the elitist reflexes of mainstream climate governance, Professor Meyer advanced a compelling alternative: understanding climate justice movements as a form of inclusive, democratic populism.

Professor Meyer’s analysis cautioned against simplistic binaries that frame populism as inherently antagonistic to climate action or that valorize technocratic expertise while marginalizing public concerns. He argued that mainstream climate policies, deeply shaped by anti-populist sensibilities, often fail to address the disproportionate burdens faced by marginalized communities. Their tendency to depoliticize climate action by presenting it as a matter of technical necessity, grounded solely in scientific expertise, not only alienates segments of the public but also risks exacerbating the very injustices that climate policies should redress.

In contrast, Professor Meyer’s portrayal of climate justice movements illuminated their emancipatory potential. These movements do not treat justice as an afterthought or compensatory gesture but embed demands for equity, solidarity, and participatory governance at the heart of climate politics. Their inclusive notion of “the people,” attention to material conditions, valorization of indigenous and local knowledge, and critique of “false solutions” all point toward a populism that is pluralist, democratic, and responsive.

Importantly, Professor Meyer’s lecture underscored that climate justice as populism offers a path forward: one that politicizes climate policy not to obstruct but to democratize it, ensuring that climate action is socially just, politically legitimate, and broadly supported. As climate change intensifies and populist pressures grow, this reframing may prove indispensable—not only for advancing climate goals but also for renewing democratic life itself.