Please cite as:

ECPS Staff. (2025). “ECPS Conference 2025 / Panel 6 — The ‘People’ in Search of Democracy.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). July 9, 2025. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00110

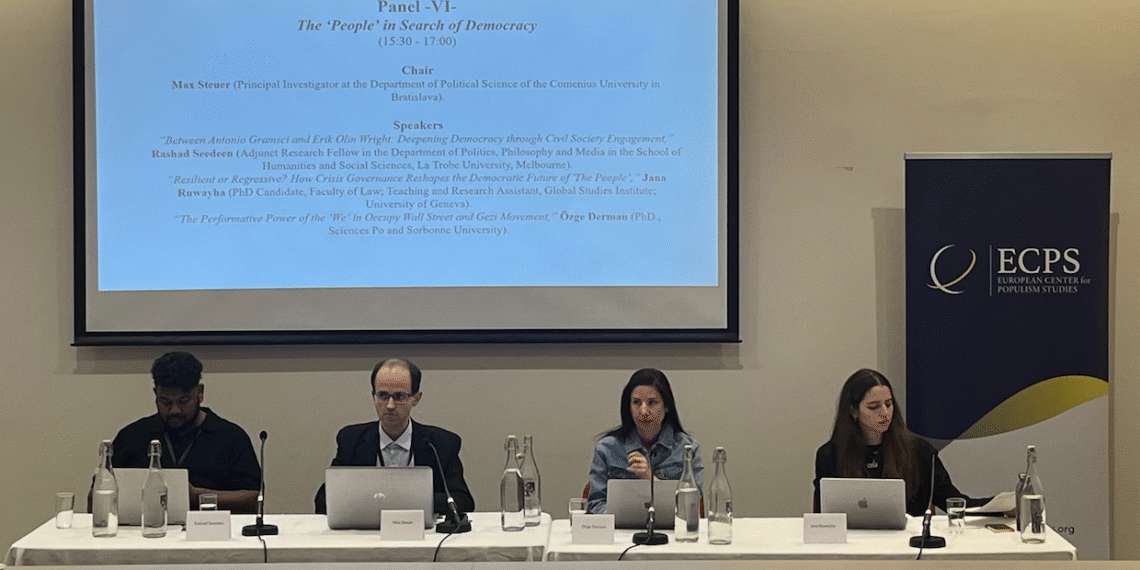

As part of the ECPS Conference 2025 titled “‘We, the People’ and the Future of Democracy: Interdisciplinary Approaches,” held at St Cross College, University of Oxford from July 1–3, Panel VI—“The ‘People’ in Search of Democracy”—brought urgent focus to the evolving meaning of democratic agency. Chaired by Dr. Max Steuer (Comenius University, Bratislava), the session opened with a reflection on whether democracy and “the people” can be conceptually disentangled. Rashad Seedeen examined how Gramsci’s war of position and Wright’s real utopias intersect in Indigenous civil society initiatives. Jana Ruwayha analyzed how prolonged emergencies blur legal norms, threatening democratic accountability. Özge Derman showcased how the “we” is performatively constructed in Occupy Wall Street and the Gezi movement. Together, the panel offered sharp insights into the plural and contested meanings of “the people” in contemporary democratic struggles.

Reported by ECPS Staff

The 6th panel, titled “The ‘People’ in Search of Democracy,” served as a dynamic and intellectually rich segment of the ECPS Conference 2025, held at the University of Oxford. It brought together three distinct, interdisciplinary perspectives on how democratic agency, civil resistance, and institutional transformation are being reshaped by contemporary crises, social movements, and emergent political subjectivities. The panel addressed some of the most urgent and foundational questions animating the future of democratic life: Who are ‘the people’? What modes of collective action best articulate democratic claims? And how do crisis, governance, and performance intersect in today’s contested political landscapes?

In his opening remarks as chair of the panel, Dr. Max Steuer—Principal Investigator at the Department of Political Science at Comenius University in Bratislava and affiliated with Jindal Global Law School—offered a thoughtful framing of the session in light of the ECPS Conference theme, “We, the People” and the Future of Democracy: Interdisciplinary Approaches (St Cross College, Oxford University, July 1–3, 2025). Reflecting on the panel’s title, he raised the provocative question of whether democracy and “the people” can—or should—be conceptually disentangled. Can there be democracy without “the people”? Steuer suggested that this line of inquiry opens new possibilities in democratic theory, particularly in relation to posthumanist and planetary frameworks that look beyond the human subject as the core agent of democratic life. At the same time, he pointed to the resilience and agency of “the people” in resisting authoritarianism—a theme that would recur throughout the panel presentations.

The panel unfolded with three carefully crafted presentations: Rashad Seedeen explored how Antonio Gramsci’s concept of war of position and Erik Olin Wright’s real utopias framework converge to reimagine democracy through grassroots civil society initiatives. Jana Ruwayha examined the normalization of emergency governance and its transformative—sometimes regressive—effects on liberal democratic orders, using the lens of legal theory and complex adaptive systems. Finally, Özge Derman illuminated the role of performative collectivity in Occupy Wall Street and the Gezi Movement, showing how “the people” emerged not through institutional structures, but through embodied acts of protest, silence, and solidarity.

Together, these interventions illustrated the multiple ways in which “the people” are both agents and constructs in the ongoing redefinition of democratic life. Dr. Steuer’s facilitation guided the panel toward an inclusive and critical conversation, allowing for reflections that transcended disciplinary silos while remaining grounded in rigorous analysis.

Rashad Seedeen: Between Antonio Gramsci and Erik Olin Wright: Deepening Democracy through Civil Society Engagement

Delivered during Panel 6 of the ECPS Conference 2025, Rashad Seedeen’s presentation offered a compelling theoretical and empirical examination of civil society as a site for deepening democratic practice. Seedeen, Adjunct Research Fellow at La Trobe University, Melbourne, proposed an analytical synthesis of Antonio Gramsci’s theory of “war of position” and Erik Olin Wright’s “real utopias” framework, arguing that democratic transformation is most viable when it combines radical institutional experimentation with strategic ideological contestation.

Framed against the backdrop of growing far-right populism and the erosion of democratic norms, Seedeen began by grounding his work in respect for Indigenous sovereignty, acknowledging the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people and emphasizing that the research was developed in solidarity with their ongoing struggles. From this ethical foundation, Seedeen outlined the stakes: democracy is increasingly under assault, particularly in contexts where marginalized communities face heightened vulnerability. The response, he asserted, must involve more than liberal proceduralism—it must entail active efforts to reconstruct power relations through civil society engagement.

Drawing on Wright’s “real utopias” project, Seedeen highlighted the normative and functional principles that underpin such emancipatory designs: equality, democracy, sustainability, desirability, viability, and achievability. A real utopia, he explained, is not a utopian fantasy but a transformative institutional form that is both visionary and grounded. However, Seedeen noted a critical limitation in Wright’s approach: a lack of attention to antagonistic social forces and historical-political context. This omission, he argued, leaves real utopias vulnerable to ideological sabotage and institutional capture.

To address this shortcoming, Seedeen turned to Antonio Gramsci, whose concept of “war of position” offered a strategic complement to Wright’s institutional vision. Gramsci, steeped in historicism, theorized the war of position as a slow, strategic contest for ideological hegemony within civil society. For Seedeen, this Gramscian heuristic provides the necessary lens to account for counter-hegemonic resistance and the need to construct “an intellectual and moral bloc” that can sustain democratic innovation against reactionary backlash. Gramsci’s emphasis on mutual education, inclusivity, and grassroots leadership further resonates with democratic aspirations of real utopias.

The analytical model Seedeen proposed—an integration of Wright’s normative-functional metrics and Gramsci’s strategic-historic lens—was then applied to a case study from Seedeen’s home country: the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria (Australia). This Indigenous-led body was established to negotiate a treaty process with the Victorian government and exemplifies what Seedeen termed “associative democracy.” Structurally, the Assembly includes elected and traditional-owner representatives, supports youth and elder voices, and uses culturally grounded deliberative mechanisms such as yarning circles and community gatherings. Moreover, it asserts Indigenous data sovereignty by maintaining a separate electoral roll and governing structures.

Central to this initiative is the Yoorrook Justice Commission, a truth-telling process that collected over 10,000 documents and testimony from 9,000 Indigenous participants, with recommendations for restitution and self-determination. Seedeen demonstrated how the Assembly and Yoorrook fulfill Wright’s principles: they aim for equality through inclusive representation; foster democratic participation through grassroots engagement; and contribute to sustainability via institutional recognition and government support. Yet challenges remain: non-traditional Indigenous residents of Victoria are excluded from representation, leading to internal critique, and as the Assembly grows, it risks bureaucratization and diminished transparency.

Gramsci’s war of position, Seedeen argued, is vital to the Assembly’s resilience. He compared two contrasting examples of Indigenous political engagement to underline this point. The failed 2023 Australian Indigenous Voice referendum, despite initial majority support, was defeated after a coordinated disinformation campaign by conservative elites. Lacking a robust counter-hegemonic intellectual bloc and suffering from strategic ambiguity and internal divisions, the “Yes” campaign faltered. In contrast, the Māori resistance to New Zealand’s Treaty Principles Bill in 2024 provided a vivid illustration of successful war of position. Māori leaders, supported by civil society and mainstream politicians, launched a multi-layered, culturally resonant protest campaign—culminating in a nationwide Hīkoi (march) and parliamentary haka that galvanized public opposition and ultimately defeated the bill.

Seedeen’s comparative analysis reinforced Gramsci’s insight: the battle for democratic reform is won not only in institutional design but also in the ideological trenches of civil society. The Māori example demonstrated the power of a coherent moral-intellectual bloc mobilized through historical consciousness, cultural symbolism, and participatory solidarity.

In concluding, Seedeen contended that treaty processes and democratic experiments like the First Peoples’ Assembly should not be viewed as endpoints but as evolving processes of radical democratic deepening. The marriage of Gramscian historicism with Wrightian pragmatism provides an essential framework for theorizing—and realizing—sustainable democratic alternatives in the face of entrenched power and populist reaction. His presentation exemplified the spirit of ECPS Conference 2025: interdisciplinary, critical, and committed to the defense and expansion of democracy through innovative, context-sensitive scholarship.

Jana Ruwayha: Resilient or Regressive? How Crisis Governance Reshapes the Democratic Future of ‘The People’

In her incisive presentation, Jana Ruwayha, a PhD candidate at the University of Geneva’s Faculty of Law and a teaching and research assistant at the Global Studies Institute, interrogated the growing normalization of emergency powers in liberal democracies and its implications for the democratic role of “the people.” Through a combination of legal analysis and Complex Adaptive Systems Theory (CAST)—a framework more commonly used in the sciences—Ruwayha provided an interdisciplinary lens to assess how governance during crises may either deepen resilience or accelerate democratic regression.

Ruwayha began by challenging the “classical emergency paradigm,” which traditionally views emergencies as temporary, exceptional, and proportional deviations from normal legal order, with the ultimate aim of returning to a pre-crisis status quo. Historically, such frameworks were rooted in legal constructs like the Roman dictatorship (limited to six months) or post–World War II constitutional safeguards in Europe designed to prevent authoritarian overreach. Emergencies were viewed as akin to a light switch: clearly demarcated, temporally bound, and reversible.

However, Ruwayha argued that this binary view is increasingly obsolete. The crises of our time—whether the COVID-19 pandemic, the global war on terror, or the Russian invasion of Ukraine—are interconnected, prolonged, and overlapping. They do not “switch off,” but instead operate on a dimmer switch of intensities, gradually embedding emergency logics into ordinary governance. This metaphor, borrowed from legal scholar Stephanie Boucher, illustrates how democratic erosion becomes incremental and opaque, making it harder for citizens to discern when normal governance ends and emergency rule begins.

To map these shifts, Ruwayha applied CAST to legal systems, conceptualizing them as nonlinear, dynamic, and interconnected networks. This approach illuminated several crucial insights. First, crises introduce “trigger mechanisms”—acute shocks such as terrorist attacks or pandemics—that legitimize sweeping emergency measures. Second, they foster “feedback loops”: public fear and insecurity generated during crises often bolster support for policies that further concentrate power and suppress dissent. Third, prolonged crises may reach “bifurcation points,” forcing democratic systems to choose between adaptation and backsliding. When states normalize exceptional measures and extend them into regular law, they risk entering a condition of “hysteresis”—a point of no return.

Ruwayha substantiated her argument with contemporary examples. In the United States, emergency surveillance powers introduced via the Patriot Act after 9/11 remain largely intact more than two decades later. In France, counterterrorism measures enacted after the 2015 Paris attacks—originally designed to combat jihadist threats—have since been repurposed to target environmental activists and migrants. Similarly, COVID-era public health laws in various countries have institutionalized digital surveillance, mobility restrictions, and data collection—many of which persist despite the waning of the pandemic.

This contamination of ordinary law, Ruwayha warned, undermines foundational democratic principles such as transparency, accountability, and proportionality. It also erodes the legal architecture designed to protect civil liberties, and fosters executive overreach at the expense of parliamentary or judicial scrutiny. At the discursive level, governments increasingly rely on crisis rhetoric—characterizing challenges as existential threats and invoking metaphors of war (e.g., “war on terror,” “battle against the virus”)—which not only legitimizes exceptionalism but also fuels populist narratives that portray “the people” as besieged by external or internal enemies.

Here, Ruwayha highlighted the paradox at the heart of emergency governance: while it is often justified in the name of protecting “the people,” it simultaneously sidelines them from meaningful participation in shaping policy. “The people” become passive subjects to be secured, rather than active democratic agents.

Against this bleak backdrop, Ruwayha turned to the notion of resilience—not as a return to pre-crisis normalcy, but as the ability of democratic systems to adapt, endure, and regenerate without abandoning core values. She outlined three pillars of resilient legal systems: Robustness – the capacity to withstand disruptions while upholding democratic norms. Adaptability – the flexibility to recalibrate laws and institutions in response to evolving threats. Recovery potential – the ability to regain full democratic functionality post-crisis without suffering permanent distortion.

Resilient governance, Ruwayha contended, requires more than legal insulation; it demands participatory structures that preserve the voice of the people during and after crises. This involves strengthening democratic feedback mechanisms, embedding civil society oversight, and ensuring constitutional safeguards that are not easily overridden by executive discretion. Drawing connections to other presentations in the panel, she emphasized that inclusive, grassroots engagement—such as citizen assemblies or bottom-up accountability initiatives—are indispensable to counter the instrumentalization of crises by populist actors.

In conclusion, Ruwayha’s presentation made a forceful case for rethinking the democratic implications of long-term emergency governance. She urged scholars and practitioners to abandon the myth of the “short-term exception” and recognize that today’s emergencies are shaping a new legal equilibrium. Whether this equilibrium is resilient or regressive, she argued, will depend on how institutions are reconfigured and whether “the people” are empowered as central actors in crisis governance. Her framework—combining legal theory with systems thinking—offered a powerful interdisciplinary contribution to understanding how democracy can be defended, not only through law, but through collective vigilance and participatory renewal.

Özge Derman: The Performative Power of the ‘We’ in Occupy Wall Street and Gezi Movement

In her richly interdisciplinary and empirically grounded presentation, Özge Derman (PhD, Sciences Po and Sorbonne University) explored how the collective “we” is visually, bodily, and discursively constructed through performative acts of togetherness in post-2010 protest movements—namely, Occupy Wall Street (New York, 2011) and the Gezi Park protests (Istanbul, 2013). Drawing on fieldwork, interviews, archival material, and theories from political philosophy and performance studies, Dr. Derman made a compelling case for understanding social movements not merely through ideological content or institutional outcomes, but through their embodied and creative enactments of solidarity and dissent.

Dr. Derman began by situating her work within a broader theoretical framework, particularly the political philosophy of Hannah Arendt and Judith Butler. As Arendt reminds us in The Human Condition, power arises when people act in concert in public space. Yet this power is inherently ephemeral, lasting only as long as people continue to appear, speak, and act together. Building on this, Butler emphasizes the performative nature of political assembly—the way bodies materialize dissent and generate public space through their presence, speech, and action. Dr. Derman took these insights further to argue that the “we” of democratic resistance is not a fixed or homogenous identity, but a precarious, plural, and performatively constituted subjectivity.

To investigate this dynamic, Dr. Derman employed a qualitative methodology involving semi-structured interviews with activists, participant observation, and analysis of both traditional and digital archives. She framed her inquiry around how the “we” emerges not from shared ideology, but from acts of co-presence, speech, and performance that reconfigure urban space and challenge hegemonic narratives.

In Occupy Wall Street, Dr. Derman observed how protestors reclaimed Zuccotti Park in the heart of New York’s financial district, creating an experimental space of non-hierarchical, direct democracy. General Assemblies were held daily, enabling collective decision-making through consensus rather than majoritarian voting. Importantly, the protestors adopted creative tools to circumvent legal restrictions—most notably, the “human microphone” (a call-and-repeat communication method) and hand signals, both of which emphasized listening, repetition, and embodied consensus. These practices disrupted conventional oratory and leadership models, fostering what activists called “leaderlessness” or “leaderfulness”—forms of horizontal organization where every voice, especially those traditionally marginalized, could be heard.

Dr. Derman highlighted how the slogan “We are the 99%” encapsulated this collective subjectivity. Far from a rigid class category, the phrase acted as a discursive and visual representation of solidarity, uniting debt-ridden students, unemployed workers, and housing activists under a shared opposition to the global financial elite. The slogan’s visual dissemination—in banners, digital media, street art, and performative projections (such as the iconic “bat signal” on the Verizon building)—allowed the “we” to materialize across physical and digital platforms.

In Istanbul’s Gezi movement, similar performative articulations of the “we” took root. Here, too, urban space—Gezi Park and Taksim Square—was transformed through encampments, assemblies, and artistic interventions. One of the most emblematic performative acts was that of the “Standing Man” (Duran Adam), a silent dancer who stood immobile for eight hours to protest police brutality. His non-verbal act of resistance quickly became contagious, replicated by individuals across Turkey and online. Dr. Derman described this as a moment where a single body became a performative catalyst, activating a dispersed and resilient collective “we”—a political choreography of stillness that reclaimed public space through vulnerability and silence.

Notably, Dr. Derman emphasized that these performative enactments were not free of conflict or contradiction. In both Occupy and Gezi, internal tensions emerged—from disagreements over the role of drumming collectives in Zuccotti Park, which disrupted deliberations, to ideological schisms within Gezi between secularists, feminists, Kurds, and Islamists. Yet these tensions, rather than undermining the movements, served to reveal the heterogeneity of democratic action. Drawing on Jacques Rancière, Dr. Derman suggested that these “conflictual disruptions” were themselves forms of politics—moments where the established order is contested and new forms of inclusion imagined.

Dr. Derman further examined how symbols and slogans became sites of performative identification. In Occupy, the blog “We Are the 99 Percent” allowed individuals to narrate their struggles, visually linking diverse lives into a common narrative of injustice. In Gezi, the figure of the “Çapulcu” (roughly translated as “looter”)—a term initially used by then-Prime Minister Erdoğan to delegitimize protestors—was ironically reclaimed by activists as a badge of resistance. T-shirts, graffiti, memes, and even Noam Chomsky’s public declaration (“I am a Çapulcu”) reinforced the idea of a collective identity forged through performance and creativity.

Despite the ephemeral nature of both movements, Dr. Derman argued that their performative legacies endure. The aesthetic and discursive repertoires developed in Occupy and Gezi continue to inspire new generations of protest, offering alternatives to top-down politics through acts of improvisation, embodiment, and mutual recognition. These movements did not produce traditional party structures or electoral victories, but they redefined political space, rendering visible new forms of democratic agency.

In her conclusion, Dr. Derman returned to Arendt’s formulation that power arises when people “are with others,” not necessarily for or against them. In both Occupy and Gezi, the “we” was not a predetermined category but a performative constellation—a fleeting yet potent political form. Through creative enactments of togetherness, protestors generated a space where direct democracy, dissent, and solidarity could be experimented with in real time.

Ultimately, Dr. Derman’s presentation offered a nuanced, affective, and visually rich account of how democratic subjects emerge in protest. By tracing the embodied practices, affective resonances, and symbolic innovations of two landmark movements, she illuminated the transformative power of performative “we-ness.”

Conclusion

Panel VI, “The ‘People’ in Search of Democracy,” concluded with an enriched understanding of how democratic agency is redefined in contemporary contexts of crisis, social resistance, and performative politics. From the outset, Chair Dr. Max Steuer framed the discussion with a provocative question: can democracy exist without “the people”? This critical inquiry anchored a session that interrogated democracy not as a fixed institutional arrangement, but as a dynamic field of struggle, rearticulation, and reimagination.

Through Rashad Seedeen’s synthesis of Gramsci and Wright, the panel explored how democratic deepening must be anchored in civil society’s ideological and institutional labor, especially when practiced from within historically marginalized communities. Jana Ruwayha’s legal-systems approach revealed the creeping normalization of emergency governance and the risks it poses to democratic resilience. Özge Derman’s analysis of the Occupy and Gezi movements showed how democratic subjectivities form not only through formal structures but through aesthetic, embodied acts of collective presence and dissent.

Taken together, the panel demonstrated that “the people” are not a singular, stable identity but an ever-contested construct—sometimes excluded, sometimes mobilized, always central to the democratic imagination. Whether through grassroots utopias, legal resilience, or performative solidarity, the search for democracy is ongoing, multifaceted, and urgent. Panel VI offered a compelling, interdisciplinary contribution to the ECPS Conference 2025, reminding us that democracy’s future lies in rethinking who “the people” are—and who they might yet become.

Note: To experience the panel’s dynamic and thought-provoking Q&A session, we encourage you to watch the full video recording above.