In this in-depth ECPS interview, Professor António Costa Pinto—one of Europe’s leading scholars of authoritarianism—offers a historically grounded analysis of Chega’s meteoric rise and André Ventura’s advance to the second round of Portugal’s 2026 presidential election. Far from an electoral accident, Professor Costa Pinto situates Chega’s breakthrough within long-standing structural conditions, recurrent political crises, and the fragmentation of the center-right. He traces how Ventura mobilizes authoritarian legacies of “law and order,” welfare chauvinism, and anti-elite resentment without openly rehabilitating Salazarism. Immigration, demographic change, and plebiscitary populism emerge as key drivers of Chega’s success. Crucially, Professor Costa Pinto argues that Orbán’s Hungary—not Trump or Bolsonaro—serves as Ventura’s primary model, raising urgent questions about democratic resilience in Portugal as uncertainty on the right deepens.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

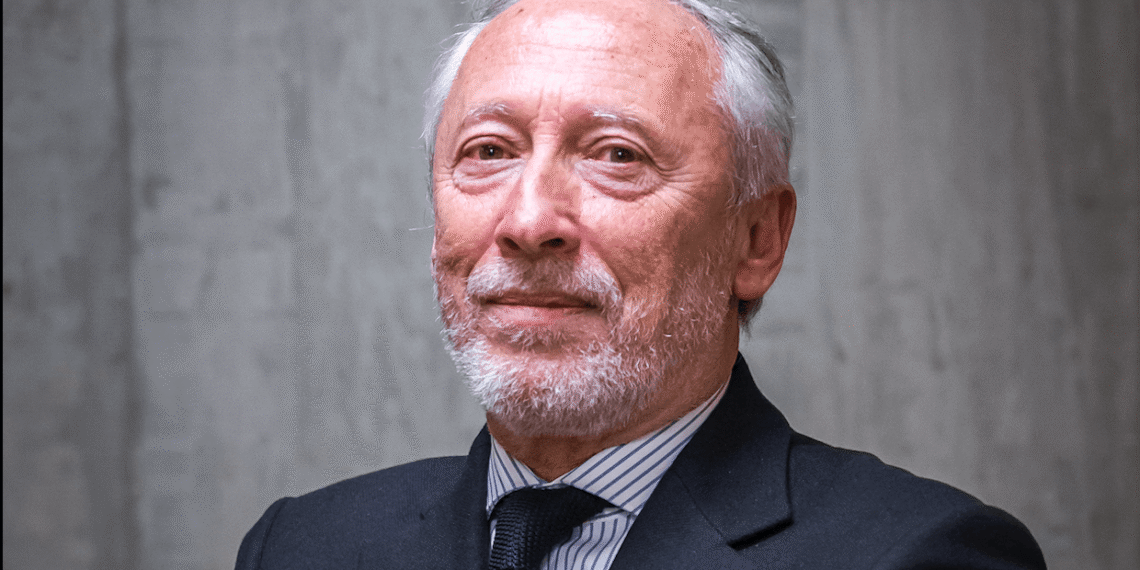

In this in-depth interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor António Costa Pinto—Research Professor (ret.) at the Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, and a leading authority on authoritarianism and the radical right—offers a historically grounded analysis of the unprecedented rise of Chega and its leader, André Ventura. The discussion is anchored in a critical political moment: Ventura’s advance to the second round of the 2026 presidential election, which Professor Costa Pinto describes as neither a mere accident nor a sudden rupture, but the product of deeper transformations within Portuguese democracy.

As Professor Costa Pinto explains, Chega’s breakthrough cannot be understood as an isolated electoral shock. “The Chega Party and André Ventura have, in a way, a short history in Portuguese democracy,” he notes, “but over the last four years, the party has gone from one MP and 1.5 percent to 23 percent.” This rapid ascent, he argues, reflects the convergence of long-standing structural conditions—most notably the persistence of conservative authoritarian values in Portuguese society—with a series of destabilizing political crises that created what he calls “populist junctures.”

A central theme of the interview is the fragmentation of the center-right, which Professor Costa Pinto identifies as a key enabling factor. Portugal now has “three parties representing the right in Parliament,” and Chega’s strategy is explicitly hegemonic: to replace the traditional center-right as the dominant force. Ventura, Professor Costa Pinto observes, has succeeded because “he was able to mobilize his electorate,” even as his capacity to expand it in a runoff remains uncertain.

The interview also situates Chega within Portugal’s authoritarian legacies without reducing it to a simple revival of Salazarism. While Chega does not openly rehabilitate the Estado Novo (the corporatist Portuguese state installed in 1933), Professor Costa Pinto notes that it selectively draws on the past, particularly through “law and order” and moral authority. “Salazar is presented as the example of a non-corrupt dictator,” Professor Costa Pinto explains, adding that Chega appropriates “the idea of a conservative regime in which law and order prevailed,”while avoiding deeper identification with an unpopular dictatorship.

Immigration emerges as the party’s most powerful mobilizing issue. According to Professor Costa Pinto, “the central card that Chega has been playing over the last four years—and one that is closely associated with its electoral success—is immigration.” He links this to recent demographic shifts, especially increased migration from South Asia, and to growing anxieties among working-class voters. These dynamics underpin Chega’s welfare chauvinism, which combines statist social policies with exclusionary nationalism.

Crucially, Professor Costa Pinto frames Ventura within a transnational authoritarian constellation. “In a way, Orbán is the model for Ventura,” he states plainly. “The type of regime that Ventura would seek to consolidate in Portugal… is precisely the kind of competitive authoritarian regime that Orbán has managed to establish in Hungary.” While Trumpist styles and Bolsonaro’s experience in Brazil matter symbolically, Professor Costa Pinto stresses that Ventura adapts these influences pragmatically to Portuguese political culture.

Ultimately, the interview raises pressing questions about democratic resilience. While Professor Costa Pinto believes that Ventura is unlikely to win the presidency, he cautions that “the game is not over” on the right. Portugal, he concludes, faces a period of sustained uncertainty—one in which democratic institutions remain intact, but increasingly contested.

Here is the edited version of our interview with Professor António Costa Pinto, revised slightly to improve clarity and flow.

A Historic Runoff and a Fractured Right

Professor António Costa Pinto, thank you so much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: André Ventura’s advance to the second round of the 2026 presidential election marks a historic breakthrough for the Portuguese far right. From a longue durée perspective, how should we interpret this moment: as an electoral shock, or as the culmination of structural shifts long underway within Portuguese democracy?

Professor António Costa Pinto: Let me tell you two things. First, the Chega Party and André Ventura have, in a way, a short history in Portuguese democracy. Over the last four years, the party has gone from one MP and 1.5 percent in legislative elections to 23 percent. The reason why André Ventura will be present in the second round of the presidential elections is therefore more complicated. The Portuguese center-right and right are going through a rather curious period of party fragmentation. We now have three parties representing the right in Parliament: the center-right that is in power, a liberal right with 7.5 percent, and the Chega Party with 23 percent.

The question surrounding this presidential election is, in a way, simple. There was an independent candidate who was expected to be the winner a year ago. Admiral Henrique Gouveia e Melo was a sort of hero of the response to the pandemic a couple of years ago. In this sense, the presidential election is unusual in terms of the number of candidates, with four candidates competing on the right-wing side of the political spectrum.

The reason why Ventura is in the second round is straightforward. The main reason is that he was able to mobilize his electorate. The more difficult challenge for Ventura lies in the second round: whether he will be able to expand his electorate, because, in theory, he is going to lose.

Why the Far Right Arrived Late in Portugal

Portugal was long considered an outlier in Southern Europe for its resistance to far-right populism. In your view, what factors delayed the emergence of a party like Chega, and what has changed—politically, socially, or culturally—to make its rise now possible?

Professor António Costa Pinto: There are structural factors and conjunctural factors. The structural factor is, first of all, that since the 1980s we have known already quite clearly from surveys that around 80 percent of Portuguese society has expressed conservative authoritarian values. That was very clear. The main problem, of course, was the opportunity to express these values in electoral and political terms. Until very recently, the two main parties, especially on the right-wing side of the political spectrum—and particularly the main center-right party—had the capacity, in a way, to frame and absorb this electorate to their right.

What happened in the meantime? There were two general elements. The first was what we could call a populist juncture. A couple of years ago, a Socialist prime minister, António Costa—who now holds a position in the European Union institutions—faced, while in office, an accusation from the court system. Not exactly for corruption but associated with corruption. His response was basically to resign. The president then decided to call early elections. This was the first populist juncture responsible for the initial breakthrough of the Portuguese radical right in Parliament. Over the last four years, there have been three early elections, all associated with this kind of populist juncture.

The most recent one, seven months ago, was also the result of a problem involving a conflict of interests, in which a center-right prime minister was accused in Parliament of maintaining a small family business that was incompatible with the role of prime minister. So, Portugal has experienced several electoral populist junctures over the past four years, and these conjunctural elements have driven the growth of the Chega Party during this period.

We therefore have structural dimensions, of course, but above all, we have conjunctural dynamics that explain this development. There is also a central element in this process: the leader of the Chega Party. He is a very charismatic figure, extremely well known in the media. He began as a football commentator in the press, closely connected to popular segments of Portuguese public opinion. He then emerged as a party leader, and we must admit that, for the first time in Portugal, a right-wing political entrepreneur managed to establish direct contact with potential voters of a radical right party—and he succeeded in doing so.

Old Repertoires, New Populism?

Drawing on your work on the “Estado Novo,” to what extent does Chega represent a reactivation of authoritarian political repertoires—such as moralism, punitive order, and anti-pluralism—rather than a novel populist phenomenon detached from Salazarist legacies?

Professor António Costa Pinto: When we look at populist radical right-wing parties in Europe, discussing their origins can become a political trap. Why? Because the trajectories are highly diverse. We know, for instance, that the Swedish populist party emerged from a very small neo-Nazi group; Fratelli d’Italia in Italy also originated in a marginal neo-fascist party; while in Spain, Vox comes from the center-right.

In the Portuguese case, the Chega Party has a very small core of leaders—essentially one figure—who comes from the political culture of the Portuguese extreme right of the past. However, the majority of its leadership, including André Ventura, comes from the main center-right party, as is also the case in Spain. Ventura himself ran for a municipal position many years ago through the Social Democratic Party, Portugal’s main center-right party, mobilizing a Roma-chauvinistic discourse. He contested a former communist municipality and played on anti-Roma sentiment in very populous suburbs of Lisbon, and this strategy proved effective. That was the starting point of his political career.

When it comes to the past, two elements are particularly important in the radical right’s mobilization of authoritarian legacies. These are not directly tied to Salazarism, but rather to a more homogeneous conception of the nation-state: the glorification of Portugal’s past, the narrative of the “Discoveries,” the Portuguese Empire, and, in many cases, the mobilization of veterans of the colonial wars. Portugal experienced a deeply traumatic decolonization, and this remains the central historical reference in how Chega engages with the past—especially the colonial wars in Africa, in Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau.

At the same time, and this is especially interesting, Chega represents a break with the political culture of the conservative right. Traditionally, the conservative right promoted a loose or “tropical” notion of empire, arguing that the Portuguese Empire was not racist and was, overall, a positive historical experience. Chega breaks with this tradition. Its chauvinistic, anti-immigration discourse—targeting African, Brazilian, and Asian immigration—marks a clear rupture with the conservative right’s legacy in Portugal.

What emerges, then, is a new-old conception of national identity. Chega occasionally invokes Salazar, but above all it mobilizes the past through the theme of corruption: fifty years of corruption, fifty years of an oligarchic political class—coinciding, symbolically, with the fifty years of democracy Portugal celebrated last year. Salazar himself poses a problem as a reference, as he is associated with repression and with a period that remains unpopular in Portugal, except in one key dimension: law and order.

These, ultimately, are the two elements Chega draws most clearly from the authoritarian past: the myth of a glorious colonial empire and, above all, the appeal to law and order.

Presidentialization and the Rise of Plebiscitary Populism

While Chega does not explicitly rehabilitate Salazar, do you see elements of what you have described as Salazarism’s “politics of order” and depoliticization resurfacing in Ventura’s discourse, particularly his emphasis on discipline, punishment, and national moral renewal?

Professor António Costa Pinto: As I mentioned earlier, Chega draws on Salazar primarily through two elements. First, Salazar is portrayed as an example of a non-corrupt dictator. Second, Salazarism is evoked as a conservative regime in which law and order prevailed. These are essentially the two aspects Chega appropriates from the Salazarist past. However, as I also noted, most of the references to authoritarian legacies are linked less to Salazar himself than to the former greatness of the Portuguese colonial empire in Africa.

In your comparative work on charisma and authoritarian leadership, you note that charisma need not be revolutionary or mass-mobilizing. How would you characterize Ventura’s leadership style: as plebiscitary populism, mediated celebrity politics, or a new post-charismatic form of personalization?

Professor António Costa Pinto: Ventura clearly belongs to the plebiscitary, authoritarian populist parties in Europe. By this I mean that the main elements of political mobilization of the Portuguese radical right revolve around law and order, the idea of corruption associated with the oligarchic political class that has dominated Portuguese democracy since its transition, and a set of conservative values typically linked to this form of plebiscitary authoritarian democracy—such as proposals for the sterilization of pedophiles, or even the reintroduction of the death penalty in Portugal.

These are dimensions tied to this broader political vision, and a significant segment of Portuguese society does support such ideas. As a result, this is not primarily about the functioning of parliamentary institutions, but rather about a plebiscitary, referendum-style conception of political power.

This is also how Ventura behaves in the current presidential elections. He seeks, in a sense, to use the powers of the presidency to advance many of these political proposals, through a form of presidentialization within Portugal’s semi-presidential system.

Electoral Strategies of Chega Is Cannibalizing the Right

Salazarism relied on corporatist and technocratic governance rather than mass populist mobilization. Does Chega’s rise suggest a transition from elite-managed authoritarianism to popular authoritarianism, or are we witnessing a hybrid form adapted to democratic institutions?

Professor António Costa Pinto: As with many other radical right-wing parties in Europe, Chega operates within democratic institutions. It is primarily an electoral party. There are very small segments—one could describe them as a residual effect—of neo-fascist and extreme right-wing groups, but these remain marginal. For the most part, Chega plays the electoral card.

In fact, in the current presidential election and campaign, an important dynamic concerns the right-wing side of the political spectrum in Portugal. Ventura and Chega are present, but Ventura is the only right-wing candidate to advance to the second round. His strategy is to combine two approaches: on the one hand, mobilizing the radical right and, at times, even the extreme right; on the other, presenting more conservative and moderate political proposals. The objective is straightforward: to become the main party representing the right-wing side of the political spectrum in Portugal and to cannibalize the conservative right-wing electorate.

The cards have been played, but the outcome remains highly uncertain. We will see what happens in these presidential elections, even if Ventura does not ultimately win.

Selective Moralism in Portugal’s Populist Right

Your research highlights the role of political Catholicism in shaping authoritarian moral frameworks. To what extent does Chega’s moralized discourse on family, crime, and social order echo these traditions, even in a formally secular and pluralist society?

Professor António Costa Pinto: Chega has clear, or very conservative, values associated with religion—not only with the Roman Catholic Church. We should also not underestimate the role of small evangelical groups, particularly among certain popular segments of Portuguese society. Undoubtedly, Chega has adopted pro-life positions, anti-abortion values, and other conservative stances. At the same time, however, Chega is a populist party. For that reason, it does not consistently play the anti-abortion card. Why? Because its leaders look at opinion surveys and recognize that the majority of Portuguese society supports the legalization of abortion, as is currently the case in Portugal.

What we see, then, is a core of conservative values, but above all a strong emphasis on anti-corruption rhetoric, hostility toward the political class, and the idea that Portuguese society is being held back by centrist, non-reformist center-right and center-left governments. So yes, conservative values matter for Chega, but the party does not emphasize all of them when it realizes that they do not translate into electoral gains.

There is, however, one aspect I would like to stress: As in many other European democracies, Chega is a typical social welfare–chauvinistic party. It does not embrace ultra-liberalism, unlike some other right-wing populist figures outside Europe, such as Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil or Javier Milei in Latin America. Instead, Chega clearly plays the card of a welfare state “for the Portuguese,” combined with anti-immigrant narratives that accuse immigrants of exploiting the welfare state and the national health system. At the same time, it advances a vision of social policy that is explicitly not anti-statist.

From Emigration Country to Immigration Backlash

Ventura’s campaign placed immigration at the center of political conflict, despite Portugal’s relatively recent experience as a destination country. How do you explain the salience of immigration in a context historically defined by emigration rather than immigration?

Professor António Costa Pinto: The central card that Chega has been playing over the last four years—and one that is closely associated with its electoral success—is immigration. Portugal was long accustomed to immigration from Portuguese-speaking African countries and to some extent from Brazil. However, over the past five years—a very recent development—there has been a sharp increase in immigration from Asia, which is new in the Portuguese context. Migrants from Nepal, Bangladesh, and Pakistan are now highly visible across different segments of Portuguese society and the economy, from delivery services and other forms of urban transport in major cities to the agro-export sector in the south of the country. In that sector alone, around 70 percent of the labor force now comes from Asian countries such as Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Similar patterns are visible in tourism as well.

This shift is driven, of course, by economic needs. Portugal is one of the most rapidly aging societies in Europe, and demographic aging is a central structural feature of the Portuguese economy and society. Immigrants already play a crucial role in sustaining pensions, social benefits, and key sectors of the labor market.

However, the social reaction to this new wave of immigration—particularly among lower-middle-class and working-class segments of Portuguese society—is perhaps the most important explanation for Chega’s electoral success. At the same time, as Chega has come to dominate the political agenda on immigration, the center-right government, feeling electorally threatened, has responded by negotiating with the radical right and adopting new restrictive policies on immigration, access to Portuguese nationality, and related issues.

The Crisis of the Traditional Right in Portugal

The PSD’s historically weak performance and its refusal to endorse a runoff candidate point to a crisis of the traditional right. How important is center-right fragmentation in enabling Chega’s claim to leadership of the “non-socialist space”?

Professor António Costa Pinto: Undoubtedly, Chega is cannibalizing segments of the center-right, much more so than voters on the left or the radical left. At the same time, Chega is now present in many areas of Portuguese society—particularly in the South—that were electorally communist in the past. However, this is less significant today, given that the Portuguese Communist Party now represents around 2 percent of the vote.

What is more important is that Chega has increased its vote share in many areas, especially in the south and in the outskirts of Lisbon, which previously voted for the Communists and the Socialist Party. Today, however, Chega has become a national party with a very homogeneous electorate. As a result, it is primarily cannibalizing votes from the right.

The only real challenge to Chega, aside from the center-right, comes from a small right-wing liberal party that appeals mainly to younger and more educated voters. Chega, by contrast, is clearly dominant on the right-wing side of the political spectrum among segments of Portuguese society with less than secondary education. For this reason, any further electoral growth for Chega can only come from right-wing voters.

In the last legislative elections, the Social Democratic Party (PSD), the main center-right party, did increase its vote share. It is now in power with a minority government that is forced to negotiate much of its legislation with the radical right. Labor reform is a clear example: the only viable negotiating partner is the radical right, since the center-left has already decided to vote against it.

So yes, the challenge posed by the radical right is very significant, and the game is far from over. While the cards have been played, there remains considerable fluidity and uncertainty on the right-wing side of the political spectrum. On the left, by contrast, the Socialist Party lost the election and many voters, but it has nonetheless survived as the main force of the center-left.

From Trump to Orbán: How Transnational Models Shape Portugal’s Radical Right

Observers have described Ventura’s rise as part of the “Trumpification” of the right. To what extent do transnational populist styles, media strategies, and narratives of cultural grievance matter more today than domestic historical legacies?

Professor António Costa Pinto: Domestic legacies are important, but undoubtedly Chega and Ventura are, first of all, integrated into the radical right political family in the European Parliament. There is a strong sense of identification with Giorgio Meloni, and also with Vox in Spain.

Above all—and this is very important—even when it is not openly emphasized, there is a strong sense of identification with Orbán. In a way, Orbán is the model for Ventura. The type of regime that Ventura would seek to consolidate in Portugal, if he were to win elections and gain access to power, is precisely the kind of competitive authoritarian regime that Orbán has managed to establish in Hungary.

In the Portuguese case, and in Portuguese political culture more broadly, we should not forget Portugal’s strong links with Brazil. Chega was a strong supporter of the Bolsonaro experience in Brazil, firmly anti-Lula and anti-left, and this reflects deeper cultural and political connections between Portugal and Brazil.

More recently, however, Trump’s challenge to NATO and episodes such as the “Greenland affair” have made Ventura more cautious. He is aware that, within Portuguese public opinion, Trump’s positions on NATO and the European Union are problematic. This matters because the Portuguese electorate is generally optimistic about the European Union and not receptive to such positions, so Ventura avoids adopting them openly.

So, as in many other radical right-wing populist experiences in Europe, there is a core of values associated with right-wing authoritarianism, but there is also a popular strategy that plays the cards that are popular and avoids those that are unpopular.

Uncertainty on the Right and the Future of Portuguese Democracy

And finally, Professor Pinto, from the perspective of democratic theory and historical comparison, does the 2026 election represent a critical juncture for Portuguese democracy—or does Portugal still possess institutional and cultural buffers capable of containing far-right populism in the long run?

Professor António Costa Pinto: That is a very interesting question, and it is not easy to answer. For the first time, this presidential election has prompted a clear stance among many figures on the right, including several politicians from the center-right, in support of the moderate candidate of the left. This is the first time such a development has occurred in Portugal. Why? Because in the last legislative elections, seven months ago, the Social Democratic Party completely abandoned any strategy of maintaining red lines against the radical right and entered into negotiations with it.

For the second round of the presidential election, both the prime minister and the main leader of the conservative party supporting the government chose not to take public positions. However, they gave instructions to most local leaders—mayors and other municipal figures—to support the center-left candidate. This was also a very pragmatic decision.

They know that, as president, the center-left candidate would respect democratic norms and the formal and informal rules governing relations between the president and the government. We should not forget that Portugal is a semi-presidential democracy. They also know very clearly that if, by any chance, the radical right was to win the election and Ventura became president—which is not going to happen—it could lead to a presidentialization of the system and favor his party in terms of cabinet influence.

In that sense, Portuguese democracy could be subverted not only through legislative elections but also through presidential ones, if Ventura were to gain presidential power—and that is not going to happen.

Overall, Portuguese democracy will continue to face a degree of uncertainty, particularly on the right-wing side of the political spectrum, where the game is not over. At this stage, we do not know which party will ultimately become the dominant force on the center-right. Will Portugal move toward an Italian-style scenario, in which the radical right dominates and the center-right becomes a junior partner? Or will it continue, as it does today, with a minority center-right government supported by a liberal democratic party such as Iniciativa Liberal? With Chega holding 23 percent of the vote, the future of the right-wing political landscape in Portugal remains highly uncertain.