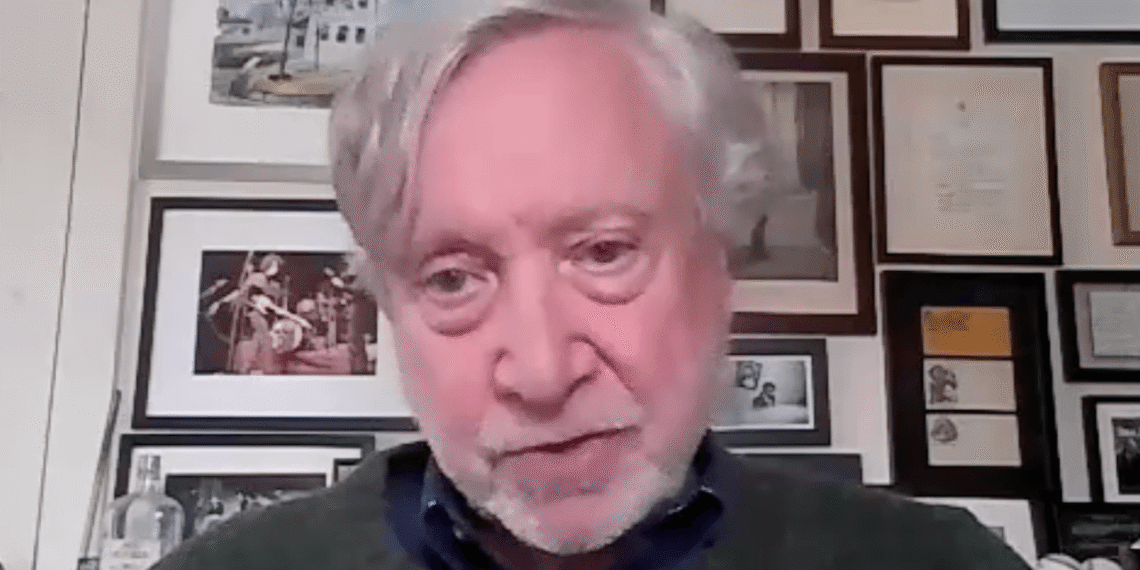

In an in-depth and sobering interview with the ECPS, Princeton historian Professor Sean Wilentz warns that the United States has moved “beyond a constitutional crisis” into a state of “constitutional failure.” He argues that the Supreme Court’s presidential immunity ruling has “turned the presidency into a potential hotbed of criminality,” effectively dismantling the rule of law. “We’re no longer living in a truly democratic regime,” he cautions. Linking America’s democratic decline to a “highly coordinated global problem emanating from Moscow,” Professor Wilentz calls for a “democracy international” to counter what he terms a “tyranny international.” Despite his grim assessment, he expresses cautious faith that “most Americans will vindicate America itself” before it is too late.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In a sobering and wide-ranging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Sean Wilentz, one of America’s most prominent historians and the George Henry Davis 1886 Professor of American History at Princeton University, delivers a stark assessment of the United States’ political trajectory under Donald Trump’s renewed presidency. “We’re no longer living in a truly democratic regime,” he warns, adding that “we’re no longer living under the rule of law, that’s for sure.”

Tracing the roots of this democratic unraveling, Professor Wilentz argues that the United States has moved beyond a constitutional crisis into what he calls “constitutional failure.” In his words, “The Constitution has failed to withstand the attacks upon it that are undermining certain basic American values and basic American rights.” At the center of this failure, he identifies the Supreme Court’s presidential immunity ruling—an “extraordinary” and “completely invented”doctrine that grants the president near-total impunity for acts committed in office. The decision, he contends, “fundamentally changed the character of the federal government,” turning the presidency “into a potential hotbed of criminality.”

For Professor Wilentz, this crisis is not merely legal or institutional but global in scope. He situates America’s democratic backsliding within a “highly coordinated global problem” emanating from Moscow. “You lift the lid and you see Putin’s influence everywhere—whether it’s Marine Le Pen or others, there he is. And certainly in the case of Trump… there are strong intimations that this is what’s happening.” He describes this network as a “tyranny international”—a transnational front of illiberal collaboration linking figures like Vladimir Putin, Viktor Orbán, and Donald Trump. To counter it, Professor Wilentz calls for a “democracy international” built on solidarity among democratic societies: “We can no longer afford to be divided… We have to think of this as something like an NGO, perhaps—a movement, an expression of something we’ve never needed before, but now, we truly do.”

Throughout the interview, Professor Wilentz situates Trumpism within a long American tradition of minority rule and reactionary politics, connecting today’s populist-authoritarian coalition to the legacies of Reconstruction’s overthrow and the racialized backlash against the Voting Rights Act. Yet, he also stresses the unprecedented nature of the current moment: “What we’re seeing today is unparalleled in American history… the authoritarians, the reactionaries, have actually taken power and are holding it.”

Still, despite his grim diagnosis, Professor Wilentz insists on retaining a measure of faith in the endurance of democratic habits. “It’s an enormous test,” he concedes, “but I still believe most Americans will vindicate America itself.”

This interview stands as one of the most forceful scholarly warnings yet about the erosion of democracy in the United States—and the urgent need for a coordinated, global democratic response.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Sean Wilentz, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

What We’re Seeing Today Is Unparalleled in American History

Professor Sean Wilentz, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let’s start right away with the first question: As a historian of American democracy who has closely tracked the Trump presidency, how do you assess the current political moment in the United States—particularly the resurgence of Trumpism in 2025—within a broader global pattern of populist and authoritarian movements? What parallels or divergences do you observe between the American case and the democratic backsliding seen elsewhere?

Professor Sean Wilentz: That’s a very good question. First of all, as an American historian, as well as an American, what we’re seeing today is unparalleled in American history. There’s been nothing like it. The closest comparison you could make is the Confederate secession over slavery that led to the Civil War—which is not, of course, a happy example or a happy parallel. But it’s also different, because here you don’t see a secession; you see the authoritarians, the reactionaries, actually taking power and holding it. They don’t have to secede to get it.

And yes, it’s frightening. There are certain direct connections to what’s going on in Europe. Some of the people who have been most instrumental in pushing the authoritarian aspect of this have had very close connections with Viktor Orbán in Hungary—actually spending time in Budapest learning how to transform a country into a kind of authoritarian regime, much like what we’re seeing Trump try to do here, and in many ways succeeding.

What strikes me most is how rapidly this has all occurred. It’s true that Trump had his first administration, which was then interrupted by the Biden interregnum. Nevertheless, since January (2025), it’s been stunning how quickly he has gone about dismantling basic American institutions and the rule of law—with the aid of the Supreme Court of the United States as well.

I can’t think of anything comparable, apart from the generalized populist wave you mentioned—a kind of revolutionary current running through the West. It’s present in every country to some degree. Nevertheless, the United States is different, and it’s happening here with remarkable speed. Because of America’s unique place in the world, that makes it all the more frightening for everyone else.

Trump Has Brought Violence to the Very Center of His Political Machinery

In your recent comments, you warned that Trump and his circle act as though “provoking and inflicting violence” are integral to their politics. How do you interpret this in light of your historical understanding of political violence as a state and populist strategy in the US?

Professor Sean Wilentz: I mean violence has always been at the forefront of American life and American politics. The best example I can think of is what happened in the 19th century, when the Union had won the Civil War and slavery was abolished. There were efforts to adjust the political system—particularly in the South—to the reality of freedom for the formerly enslaved. A period called Reconstruction was entered into, which was a kind of revolution in American democracy, expanding its possibilities to include people who had been enslaved.

That effort was undone. It was overthrown, and it was overthrown violently by groups—you may know some of the names. The Ku Klux Klan is the most famous of them—but they used violence strategically, in concert with political leaders. It wasn’t just the hoi polloi out there burning crosses and attacking people. It was very much coordinated with political elites. Violence was at the forefront of it, and without it, the effort to destroy Reconstruction would not have succeeded.

Now, we’re not seeing the same kind of systematic violence, but there’s a great deal of it—and it’s mostly being deployed by the government itself. It’s the unleashing of agencies like ICE—the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency—which has been rounding up people on the streets. It’s the presence of national troops, the National Guard, in American cities, which in itself is an act of violence just to have them there. It creates the atmosphere, the feel, of martial law—and that is what the administration is trying to encourage or build up.

So yes, violence is very much present. The climate of opinion is completely permeated by this atmosphere of violence and potential violence, almost all of it coming from the government itself. There was the assassination of Charlie Kirk, which was a very strange episode—because who knows exactly who did it. It doesn’t seem to have been particularly politically motivated, but that, of course, becomes a means for the administration to turn him into a martyr right away—a martyr for their own cause—and to use that as a pretext to further suppress, or threaten to suppress, the opposition in all kinds of ways. So that’s violence of a different kind, but it nevertheless lies at the heart of what’s going on right now. They’ve brought it to the very center of their political machinery.

The Court’s Immunity Ruling Paved the Way for Authoritarian Rule

Your essay “The ‘Dred Scott’ of Our Time” draws parallels between the current Supreme Court’s presidential immunity decision and the 1857 Dred Scott case. Could you expand on how this analogy helps us understand the Court’s transformation of constitutional meaning in the Trump era?

Professor Sean Wilentz: Just to fill in, the Dred Scott decision of 1857 was a very important one in American history—perhaps the most important until now, or at least the most notorious. The then–Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Roger Taney, wrote a decision in which he basically said that the government could do nothing to prevent the spread of slavery into the territories of the United States, that slaves were property according to the Constitution, and then went on to declare that Black people had no rights which white people were bound to respect.

It was a notorious decision because it was—ironically—based on the method we now associate with so-called originalism: going back to the framers of the Constitution, interpreting what they said and meant, and then coming up with your own, essentially distorted, idea of their intentions. That was certainly the case with Roger Taney, and it played a fundamental role in hastening the coming of the American Civil War.

So that’s why it was so notorious. Now, what we see in the current Court is somewhat different. It’s interesting—they claim to be originalists, much as Roger Taney was an originalist, which is a kind of bogus judicial theory. But what they have done is to give the president absolute immunity from criminal action for anything he does in office, so long as he can describe it as an official act.

That, in many ways, is a more dangerous decision than Dred Scott, because it grants the president extraordinary power to do all the kinds of things that Trump is doing now. The decision was just as threadbare, just as weak, just as poorly reasoned as Taney’s ruling. But unlike Taney’s decision, it simply invented things—there is no constitutional basis whatsoever for that immunity ruling.

They simply asserted the need for presidential authority and did so in such a sweeping way that it has paved the way for what we’re seeing now. I liken the two because both were dramatic decisions that changed the character of the political situation—decisions that, in the first case, led to Civil War, and in the second, I hope will not, but that have nonetheless had a comparably destabilizing effect.

Both are, to put it plainly, intellectually barren and corrupt—beneath contempt, really—for anyone who studies these matters seriously as a question of law. And the fact that the Supreme Court has gotten away with this is another example of what we’re up against, because it’s not simply coming from the White House—it’s also coming from the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, from a supine Congress and a complicit Supreme Court.

What We’re Seeing Is Not a Crisis but a Constitutional Collapse

You have described the immunity rulings and the Supreme Court’s handling of the Fourteenth Amendment as “a historic abdication,” arguing in “The Constitution Turned Upside Down” and “A Historic Abdication” that the Court has effectively inverted the amendment’s logic. Do you believe this moment represents a constitutional breaking point—or a severe but reversible deviation—and what does this inversion reveal about the evolving relationship between federalism, judicial power, and democratic accountability?

Professor Sean Wilentz: I’m a historian and I don’t want to predict, but there’s no question that this is a fundamental break with what constitutional precedent has been. And it’s kind of draped around a particular theory, which is not originalism, which was there before, but this idea of the unitary executive. The unitary executive is another kind of right-wing, fake philosophical or judicial principle, which says that basically the president can do whatever he wants in administering the executive branch, including interfering with agencies that have been established by Congress, not by the executive, to administer the laws that Congress has passed and the president has signed.

This is, again, another break from what has been present in the United States for centuries. This is something completely novel, and it’s something extremely destructive. So, to that extent that originalism helped bring us some of the more cockeyed decisions that we’ve seen over the last 20 years even—this theory now has thrown the Constitution up for grabs as to what the Constitution actually means. It no longer has the stability that it had before. Things are very unstable with this Court.

There was another point that I wanted to make regarding the Fourteenth Amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment is a crucial document in American history. It was one of the Reconstruction Amendments—I was earlier talking about the Reconstruction period in American history—that involved the passage of three basic amendments: the abolition of slavery under the Thirteenth Amendment, the guarantee of equal protection under the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment, and then the guarantee of suffrage rights in the Fifteenth Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment came up for discussion when the state of Colorado wanted to keep Trump off the ticket in 2024 because he had engaged in insurrection on January 6th. In the aftermath of the Civil War, in the Fourteenth Amendment, there’s a section that said quite explicitly that anyone who had engaged in an insurrection against the government of the United States should be ineligible for any future office, both state and federal.

It couldn’t have been plainer, couldn’t have been clearer. And the fact that Trump had engaged in the insurrection meant that states control election laws—this gets back to the federalism issue. The states control who gets to be on the ballot in their particular state and who doesn’t. It’s not a national decision. Colorado perfectly had the right to do so. The Colorado courts, the Supreme Court, decided that Trump had engaged in insurrection and therefore he was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court Has Dismantled the Foundation of American Citizenship

What the Supreme Court did was basically gut the Fourteenth Amendment. It came up with this completely—I won’t go into details; it’ll bore your listeners—but a bogus explanation for why the plain language of the Fourteenth Amendment should not be adhered to, and basically let Trump stay on the ballot. It then went even further in basically saying that in order to have anything like this happen, Congress would have to pass a law to enact the amendment into effect. Because Congress had not done so, therefore the amendment was not in effect.

This is an extremely dangerous way of looking at these important amendments, because by that logic, slavery has never actually been abolished in the United States, because Congress never passed a law to enact the Thirteenth Amendment. Now, that’s an extreme way of looking at it, but we’re in extreme times. Let me make that clear to everyone. I don’t think that slavery is about to be brought back to the United States, but nevertheless, the logic of their decision was one where that would have been possible.

So the Constitution—and especially those amendments, the Fourteenth Amendment in particular, which was kind of the linchpin of what one historian has called the “Second Founding”, the post-slavery founding—involved not just the rights of the freed former slaves being protected and expanded, but, more generally, rights being extended to the American people as a whole, because the revolution that got rid of slavery was revolutionizing the entire idea of American citizenship.

Which brings me to my final point, which is that another feature of the Fourteenth Amendment was what we call birthright citizenship, which stated that anyone who was born in the United States is automatically a citizen of the United States. This was a way to protect the rights of the former slaves, to be sure, but it also—and this was explicitly stated by the people who framed this amendment at the time—meant that anyone from around the world, in this asylum of freedom that the United States is supposed to be, who is born here, is actually a citizen here.

The Supreme Court is on the brink of getting rid of that—of nullifying it, or severely modifying it—to say that if you’re here illegally, or you don’t have the proper papers, therefore you’re not a citizen. This is a complete gutting of what the Fourteenth Amendment was all about.

So, in these ways, yes, it’s a constitutional crisis—but it’s beyond a constitutional crisis. We’re now in a case of constitutional failure. The Constitution has failed to withstand the attacks upon it that are undermining certain basic American values and basic American rights.

The Supreme Court Has Turned the Presidency into a Hotbed of Criminality

In your writings on “The Immunity Con,” you suggest that legal arguments for presidential immunity constitute a deliberate distortion of constitutional tradition. How do you assess the intellectual and political origins of this distortion?

Professor Sean Wilentz: Ideological zealotry and a kind of—I don’t want to say corruption in the sense of people being bought off or something—but a kind of intellectual corruption, aimed at creating a different kind of political order. These are the hard-line conservatives on the Court—Justices Thomas and Alito, and to a certain extent, Justice Gorsuch. They hold a very radical view of what the United States ought to look like—a radical, reactionary view—and they are imposing it. They have enough support from the rest of the Court—Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh—to prevail. This is something they believe reflects the framers’ intent, but it is, in fact, a fundamental departure from it.

The immunity decision, as I said, is not based on any constitutional principle whatsoever. It’s completely made up—out of thin air—and it has fundamentally changed the character of the federal government. If you have a three-branch government that’s supposed to be based on checks and balances—in other words, the president is not all-powerful; his powers can be checked by Congress and by the Supreme Court, and vice versa—it’s a system very delicately designed to prevent the kind of tyranny and demagoguery we’re seeing now, to ensure that no one can be all-powerful.

They have found a way because they have a supine Congress—a Congress that will never defy the maximum leader, Trump—and a Supreme Court that’s going along with it for its own reasons. So we end up with something like the immunity decision, which gives the president, as I said, virtually complete power—to the extent that, as came up in opening arguments in the case, if the president deemed it an official action to assassinate one of his political rivals, he could not be prosecuted for that crime. That’s extraordinary by any stretch of the imagination in a Western democracy—that you can literally murder your political opponents because you consider it an official act. That’s giving away the ballgame. We’re no longer living in a truly democratic regime. We’re no longer living under the rule of law, that’s for sure. And that’s the power the immunity decision gave to the president.

So, quite apart from even the checks and balances, just in terms of the basic ideas of the rule of law, it’s turned the presidency into a potential hotbed of criminality. And depending on who is in the White House, we’re seeing right now how criminality, if given a chance, can metastasize like a cancer.

The Cultural Roots of Trumpism Run Deep

Do you see Trump’s authoritarian populism as primarily a legal-constitutional threat, or as a deeper sociopolitical phenomenon anchored in culture, identity, and media ecosystems?

Professor Sean Wilentz: It’s both. But the cultural underpinnings of this have been around for a very long time. This is part of the broad sweep of American history—forever, really, but certainly since the 1960s. What some of us think of as the advances of the 1960s was a sort of second Reconstruction, if you will, which sought to undo what had gone wrong the first time around and give Blacks in particular—but not just African Americans—equal rights. This is a reaction against that. And it has to do most fundamentally with the issue of voting—trying to repeal the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was a great breakthrough, really an extension of the 15th Amendment, to guarantee Black rights. So the sweep was always there. Those cultural and political aspects have been present for a long time. What’s happened now, though, is that what the Trump people—and the people behind Trump—have done is tap into those resentments, seize power with them, and turn it into a constitutional issue.

Now they’re trying to undermine the Constitution. Before, you had plenty of politicians in the Republican Party in particular—the Democrats had other problems—but the Republican Party especially was tapping into these resentments, which showed up in all kinds of ways: in religious politics, in deregulation politics, in attempts to combine what was a traditional conservative agenda—basically pro-business, low taxes, deregulation, breaking down the New Deal, which was our sort of weak version of social democracy—trying to get rid of that. But now it’s become much more radicalized.

Under Trump, that tapping in is the same; it’s just been heightened because Trump is a demagogue unlike anything we’ve ever had before. We had George Wallace from Alabama, a segregationist racist who ran for president and tapped into similar sentiments, but he didn’t succeed. We’ve had difficult presidents, like Richard Nixon, for example, but even Nixon, for all his excesses, still understood the constitutional order in a very different way than Trump does. Trump has no use for the constitutional order at all. What we’ve seen—just to answer your question again—is that these cultural and social forces essential to Trumpism, though present all along, have now been turned into a true constitutional crisis unlike anything we’ve ever seen.

Minority Rule Is Now the GOP’s Central Strategy

In “The Tyranny of the Minority, from Calhoun to Trump,” you trace a lineage of minority rule in American history. How does Trumpism fit within this long tradition of counter-majoritarian politics, from John C. Calhoun’s antebellum theory to the modern GOP?

Professor Sean Wilentz: The modern GOP has been—this is part of what I was saying earlier about the reaction against the Second Reconstruction. The modern Republican Party managed, under Ronald Reagan, to do an extraordinary thing: to create a national majority that swept to power twice in crushing elections in 1980 and 1984. They believed that they had created a political coalition that would last forever and could never be undone. But it did get undone, and as a result, the Republicans launched a process whereby they realized they were not going to be the majority, so they were going to have to do what they could to install minority rule. In other words, a minority was going to have to rule the country—and how do you go about doing that? In all sorts of ways, even before the current Trump regime, the Republicans had been doing their best to make sure that the minority would rule.

They did so in all kinds of ways, but the most fundamental one was to suppress the vote—by getting rid of the provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and using whatever powers were available to them to redistrict. In the United States, each state gets to draw its own districts—its congressional as well as state legislative districts. And these days, with computers, you can draw those lines very precisely, so that even though a majority might, in fact, be against you, you can draw the lines of the congressional districts and so forth to keep the overall minority in power, having an overwhelming majority of congressional representation. It’s less the case with the presidency, because the presidency is elected in a very different way, but there are ways to suppress the vote there as well. For example, requiring voters to provide all sorts of documentation that they are citizens—something that was never necessary before. Ordinarily, in the United States, you sign up to register to vote, and you get to vote. Now, you’re expected to show all kinds of documents that most students, younger people, minorities, and less well-off people—many of whom are Hispanic and Black—don’t have. They don’t have passports, for example. They don’t have the kinds of documents that are now required in order to vote. These laws have been brought in to make it much more difficult for people to vote, so that, quite apart from redistricting, it’s suppressing democracy. It’s anti-democratic.

These are things that the Republicans have been doing for some time. It’s just that now, under Trump, they’ve been magnified and made even more obvious. In the old days, conservatives running for office would never say they were trying to suppress the vote. Trump is absolutely unashamed about it. He says, “We don’t like Democrats. We think Democrats are communists. We think Democrats are not loyal citizens, and we are against them.” And so they’re not going to make any bones about what they’re doing.

The Normalization of Martial Law Threatens the 2026 Elections

What’s truly alarming in the wake of what’s happened recently—we have an election coming up in 2026, what we call our midterm elections: not a presidential election, but the entire House of Representatives and one-third of the Senate, the upper house, are up for re-election. In anticipation of that, there’s been all kinds of wild gerrymandering going on—redrawing of districts to boost the Republican vote. But once you start sending the National Guard into American cities under completely phony pretexts—that crime has gotten out of hand, or that there’s some great mob action going on—it’s all lies. But once you’ve sent troops into American cities, you’re normalizing, in effect, martial law—or the precursor to martial law.

When you think about the fact that an election is coming down the pike in just about a year’s time, you worry about whether this normalization of a military presence in cities is going to be used to try to suppress the vote. Either through the presence of the National Guard in cities—and these are Democratic cities, with large Black populations and liberal white populations—or through the presence of federal or National Guard troops with guns and all of that, as well as ICE, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which is rounding up and pulling Hispanic people off the streets and terrorizing them. And you can imagine what they could do in terms of intimidating people from going to the polls. So this goes beyond the more traditional voter suppression that we’ve been used to for a long time and have tried our best to fight.

This now becomes a military or violent situation—suppressing the vote in a way that’s not unlike what I was talking about earlier with Reconstruction and the use of violence then. The Ku Klux Klan, those hooded vigilantes, were most effective in trying to suppress the vote. They didn’t want newly freed Blacks to vote, and so they would intimidate them in all kinds of ways. That’s voter suppression in the late 1860s and early 1870s. Now we’re seeing it in a different form in 2025. And if Trump goes through with what I fear he’ll go through with, then we will not have an honest election in 2026. One thing about Trump is—almost psychological—you can always assume that whatever he is doing, he’s going to accuse you of doing. So if he’s accusing you of rigging elections, you can be sure that he’s trying to rig an election. If he’s accusing you of voter suppression, you can be sure that he’s intending voter suppression. This is not just a psychological tic; this is, in fact, how he operates in many ways. He does something and then accuses you of having done it. Which makes me all the more nervous. So, these are not happy times. These are gloomy times, for the most part. I don’t want to sound as if we’re hopeless—not at all. Trump is a very unpopular president.

The Republican Party is not very popular. We’re in the middle of a government shutdown now, basically over healthcare, where the Republicans won’t budge on making major cuts to American healthcare provisions. And most Americans are blaming the administration and the Republicans in Congress for that shutdown, which is affecting people—and will affect them more and more. Those are public opinion polls; that’s not power, but it’s an indication of just how unpopular he is.

If Goebbels Had Fox News, He’d Have Been the Happiest Man Alive

Now, we all know there have been plenty of unpopular regimes that have been very powerful and have done world-historic damage to Europe in particular—but not just to Europe. And you don’t have to have the majority behind you in order to rule. That is quite true. The United States, however, unlike many of the democracies in Europe—if you go back to the 1930s, say, the Weimar Republic was a very new thing, and democracy was not very well rooted—we do have a 250-year history behind us, and these are institutions that he has shown to be much more vulnerable than people thought they were. But there are still—I don’t want to cite de Tocqueville all the time—but we have “habits of the heart,” as he put it. There are ways in which Americans have certain assumptions about what democracy is and ought to be that I still don’t think have been completely wiped out.

It is true, I’m somewhat amazed, for example, to watch Trump tear down part of the White House—a great symbol to Americans of democracy—and do so arrogantly, installing a kind of dictator chic with this gigantic new ballroom he’s building and all the rest of it. It’s an assault on the American Republic, on the aesthetic of the American Republic, on a building we think of as belonging to the people, not to him. To be doing that in symbolic ways is a wrenching experience. However, there’s no crowd outside, no demonstrations. We have these “No Kings” demonstrations every once in a while, but that’s about it. There’s an eerie kind of acceptance of what’s going on, which is also historically reminiscent of things that have happened elsewhere—where either people just don’t believe what they’re watching, what’s before their very eyes, or they don’t see it.

They also lack historical understanding. In Europe, you have a much clearer sense of history than we do. Americans are always living in the present, and social media doesn’t help in that respect. So we don’t have an instinctual reaction to all of this. But still, nevertheless, I think that when push comes to shove, I hope and expect that the American people will vindicate America itself. And that things have not become so distorted—either by propaganda media, Goebbels-like media. If Goebbels had Fox News, he would have been the happiest man in the world. There’s nothing better than that—television, social media. Can you imagine if he had more than radio, which the Nazis used so effectively in the 1930s? Imagine what they’d have now.

This is all a gigantic obstacle. Nevertheless, I still have the feeling that most Americans are not going to fall for this stuff when push finally comes to shove. How it’s going to be expressed politically is another issue, and that gets into the Democratic Party and other questions, but I’m still kind of hopeful.

We’re No Longer in Normal Politics—That Illusion Must Be Broken

You’ve written that the events of January 6, 2021, were not aberrations but logical outcomes of institutional structures favoring minority rule. How can historians help the public understand that such crises are systemic rather than episodic?

Professor Sean Wilentz: With January 6th, that was a break in many ways, because what you saw was systemic, but it was more the result of the Trump phenomenon—of Trump’s hold over this very violent and very angry segment of the population that has no respect whatsoever for constitutional norms. So I think of January 6th as having echoes in American history, but it was a defiance of everything we’ve thought of. I mean, what president has ever tried to reclaim power after losing an election? Some may have extended their terms or contested results through legal means every once in a while, but one of the aspects of the genius of American politics has always been that there is opposition, but it’s a loyal opposition—that you’re loyal to the Constitution.

Even if you are disappointed in your own political efforts, you nevertheless respect the Constitution, and your loyalty remains there. You give way with the expectation that, down the line, you’ll be able to defeat your opponent and take power back. That’s not what’s going on here. The insurrection in 2021 was an indication of how different this was from anything we’ve seen before. So, for a historian, it’s more a question of marking the difference than looking for some sort of similarity or institutional basis for what’s going on here. There is no institution. The norms are broken at every step. The courts were actually completely against what Trump was trying to do, which was to steal an election. Again, it goes back to this: he accuses you of stealing an election because he’s stealing an election.

Yes, it’s different. But the aftermath of that is extraordinary. Now that he has power, now that he took that power, he has pardoned them all. And the court has upheld all of those pardons—an extraordinary use of pardon power, again a perversion of what the framers had in mind. So here’s really the point. I think that there are many Americans—I don’t know if it’s most Americans anymore—but many still think that we’re in normal politics, in normal times. That this is a Republican president who is perhaps a little unorthodox, a little extreme, perhaps, but nevertheless just a normal politician, a normal party. That is a great demobilizing illusion that has to be broken.

By pointing out what January 6th was all about, we can try to break that illusion—to show that, in fact, these people are basically, some of them at any rate—and they’ve actually announced as much—out to overthrow the United States government, period. And that’s what they’re doing, bit by bit, in fits and starts. They’re keeping the Constitution—or their own idea of it—although a Constitution with an immunity decision behind the president is no longer the Constitution we knew. It’s just not. People have to understand that. And to say it the way I just said it, even now, alarms a lot of people—even those who are already alarmed—but to hear that the stakes are that high makes people think I’m kind of nutty or extreme in my own view. I don’t believe I am, at least as far as intentions are concerned.

I do think there are people in the Trump camp who want to overthrow the government. They won’t call it that. They may have Leninist or Bolshevik techniques, where the end justifies the means, but no one’s going to call themselves Vladimir Lenin—they’re going to call themselves George Washington. But they’re going to overthrow the government in the name of the government. That’s really the key to this kind of authoritarian move: you’re not doing it to destroy anything, but to vindicate what you claim the government actually means. Yet, in doing so, you completely abolish the government as it existed previously.

Trump’s Populism Is a Tool of Oligarchy, Not a Voice of ‘the People’

As you note, Trump’s movement invokes populism yet depends on entrenched minority power. How do you reconcile this paradox—of populism serving oligarchic and exclusionary ends?

Professor Sean Wilentz: It’s exclusionary of certain people, to be sure. It’s classic in terms of authoritarian regimes: you have a despised other, as it were. In this case, it’s the immigrants, particularly Hispanic immigrants. So you focus a lot of popular rage on that group. Now, that group’s very large. But populism here is not about all of the people; it’s about some of the people—and some of the people having advantages over, or directing their anger and rage at, another part of the people. That’s what modern populism is about. It’s not very different from what we might have talked about in the 19th century.

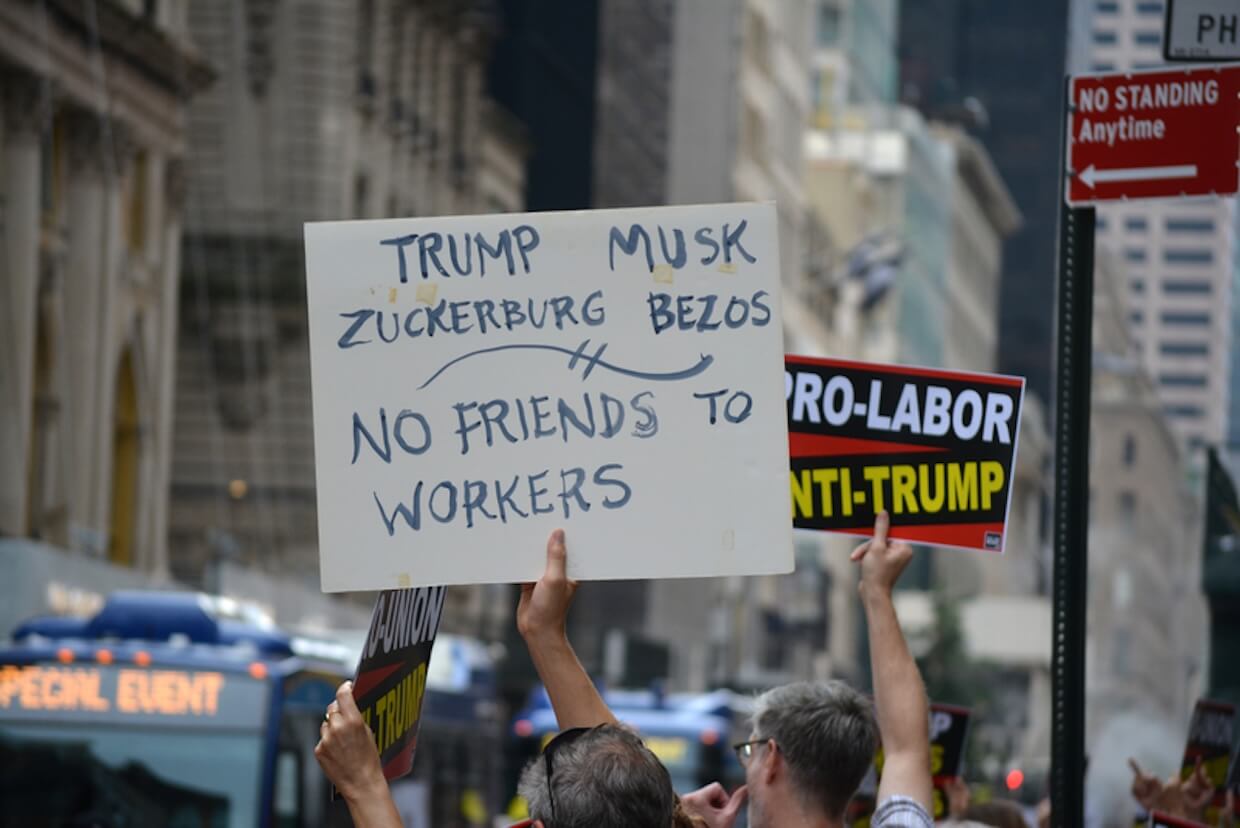

But there’s also the alliance—this is classic—using populist methods to stir up discontent and anger, some of it quite understandable, even justified. People are not doing so well in many parts of the country. History has not been on their side economically in many parts of the country, and that breeds all kinds of resentments and anger, and that’s perfectly understandable. But the question is, in what direction do you take that? And it’s been exploited. In a more normal situation, it was exploited by certain corporate elites. You see them all the time—the Koch brothers, for example, that deregulation family. Conservative, right-wing businessmen with enormous resources use this populist rhetoric to enrich themselves greatly. That’s an old pattern—the elite use of populist rhetoric to give themselves more power than ever—and that’s what we’re seeing, that’s what we have seen.

The danger, though, is when you have a political manifestation that is not simply interested in increasing inequality, which is a very real problem, but in doing so in a way that will not only entrench an oligarchy—which is what we’re seeing—but also destroy American democracy full bore. And that’s what we’re seeing now. It’s the same kind of alliance. Look at all the people supporting Trump. Someone told me that Kamala Harris expressed surprise that the titans of American industry would throw in with Trump. I’m not surprised at all.

If you look at the people helping to support, for example, the rebuilding of the White House—Amazon, and you go down the list—it’s just one large corporation after another. They now see in Trump the future for themselves. They may, behind the scenes, be saying, “Oh, this man’s a little bit too much, I’m not really for him.” Nevertheless, they’re going to go along with him because they think their interests are going to be better served. That’s what gets very, very dangerous—when that kind of populist movement of the corporate elite, the very rich, powerful private institutions, taps into what you think of as the demos, the people, in order to destroy democracy. That’s what we’re seeing. I’ve never seen that before.

We Need a ‘Democracy International’ to Counter the ‘Tyranny International’

And finally, Professor Wilentz, as a historian of American democracy, do you believe the American experiment still possesses its self-corrective capacities—or have structural inequities and partisan realignments permanently undermined them?

Professor Sean Wilentz: That’s a good question. I wish I knew the answer. I said before that I have faith, but we might call it a faith-based initiative in some ways. It’s not quite religious, but it’s certainly more spiritual than institutional. Still, it’s not just that. I think the institutions have shown themselves to be far more vulnerable than we ever expected or could have imagined—not just in terms of domestic affairs, but in foreign policy as well. The speed with which the U.S., for example, dismantled the Agency for International Development—the USAID—which did extraordinary work around the world, was shocking. It was destroyed in the twinkling of an eye. So we realize not only that they are more powerful, but that we are more vulnerable as democrats, with a small “d.”

As a historian, I must say this moment reveals vulnerabilities we’ve never seen before in American history. There have been moments—you have to go back, actually, to the 1790s, when the country was just getting started—when there was a question about whether militaristic or reactionary forces would end up controlling the government. But they were beaten back then. It’s interesting—one of the laws that Trump has invoked is among the last of the great repressive laws from 1798, a period Thomas Jefferson called the “Reign of Witches.” The fact that Trump has had to reach that far back is telling. So there have been precedents, but nothing on this scale.

It’s an enormous test. I hate to sound inconclusive—I wish I had a firmer sense of things—but as a historian, I can only say that what we’re facing is something we’ve never seen before. My great hope, actually, is not only with the American people but also with Europe. We’re going to have to find a way to establish a democracy international, it seems to me. The communists had their international—we need one of our own, a democratic international—built on much closer coordination between you in Brussels, in Paris, throughout Europe, and us here. Because this is an international, even global, problem.

It’s a highly coordinated global problem, and much of it emanates from Moscow. You lift the lid and you see Putin’s influence everywhere—whether it’s Marine Le Pen or others, there he is. And certainly in the case of Trump, while one can’t know for sure, there are strong intimations that this is what’s happening. That’s a kind of tyranny international. We need to establish a democracy international to counter it. It’s something we all ought to be thinking about much more seriously, because there is strength in numbers. We have to coordinate our activities. We can no longer afford to be divided. We can no longer rely solely on our governments. We have to think of this as something like an NGO, perhaps—a movement, an expression of something we’ve never needed before, but now, we truly do.