Please cite as:

Bolin, Niklas. (2024). “A Speed Bump in the Road or the Start of an Uphill Journey? The Sweden Democrats and the 2024 European Parliament Election Setback.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024.https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0085

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON SWEDEN

Abstract

Leading up to the 2024 European Parliament election, much attention was given to the anticipated gains of populist parties across Europe. While some populist parties made significant advances, the overall outcome was more moderate than expected. Sweden deviated from this general trend, witnessing gains for left-wing parties and a surprising setback for the populist radical right. The 2024 elections marked a historic decline for the Sweden Democrats, the first instance since their formation in 1988 that they regressed in comparison to previous national and European Parliament elections. This decline is particularly notable following their strong performance in the 2022 national elections, where they became Sweden’s second-largest party. This article examines these developments, drawing on existing research, media reports and exit polls, with a focus on the Sweden Democrats’ campaign strategies, election results and voter behaviour. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications of these election outcomes for both Swedish domestic politics and the broader European political landscape.

Keywords: radical right; populism; Sweden Democrats; European Union; elections, voting behaviour

By Niklas Bolin* (Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden)

Introduction

The expectations for the European Parliament elections among parties to the right of the mainstream right were certainly high. Media forecasts were clear, proclaiming that ‘a populist wave surges’ (Vinocur, 2024) and ‘a far-right takeover of Europe is underway’ (Vohra, 2024). The question was not whether the disparate group of far-right parties would gain influence but how significant that influence would be. However, while the results must be seen as a success for these parties, it is probably more accurate to describe it as moderate rather than a landslide victory. While some parties – for example, the French National Rally, the Brothers of Italy and the Alternative for Germany – made significant gains, the development was more modest elsewhere.

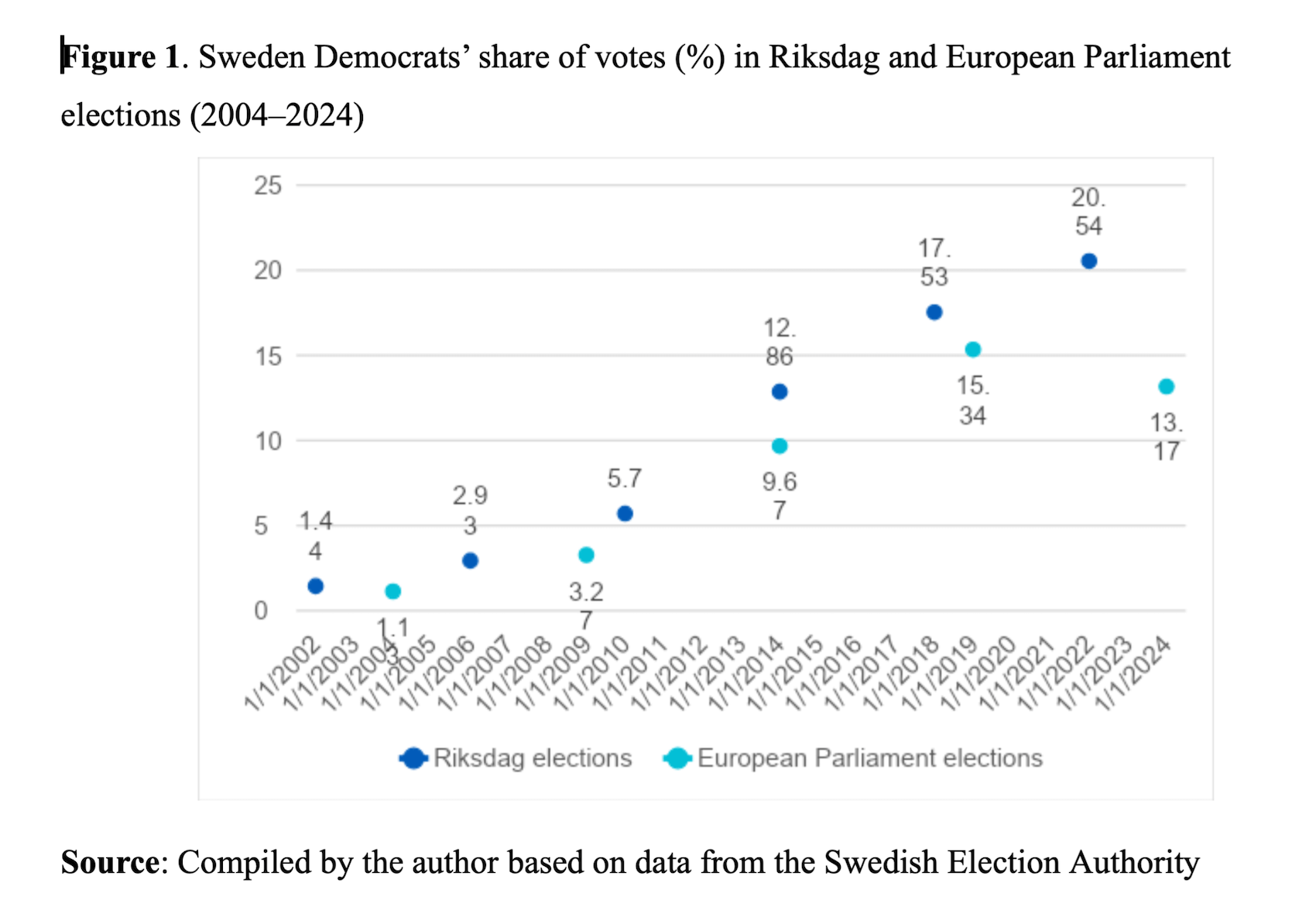

Sweden was one country bucking the trend. Parties on the left made gains while parties on the right generally fared somewhat worse. Most surprisingly, it was a defeat for the populist radical right. The 2024 European Parliament election will go down in history as the first election ever where the Sweden Democrats regressed compared to the previous election. Until this point, the party was unique in the sense that in all national elections – both to the national and the European Parliament – since its formation in 1988, it had advanced compared to the previous election. The decline is even more remarkable given that the general expectation was for the party to continue its trend of success. Instead of repeating the achievement from the national parliamentary election in 2022, when it attracted more than 20% of the votes and became Sweden’s second-largest party for the first time, the party experienced a shock. On election night, it became clear that they were not only far behind the result of the 2022 national parliamentary election but also lost ground compared to the previous 2019 European election. Rather than continuing its surge, the party only managed to secure 13% of the votes, making them merely Sweden’s fourth-largest party.

Against this background, this chapter addresses party-political populism in Sweden in connection with the 2024 European Parliament election. Specifically, it describes and analyses the populist radical right Sweden Democrats, with a focus on the campaign, the results and voting behaviour. The article is based on previous research, media reports and exit polls.

Populist parties in Sweden

In a European comparison, the successes of party-political populism came late to Sweden. Except for the brief presence of New Democracy in the Swedish Parliament (the Riksdag) from 1991 to 1994, populist representation was absent until 2010, when the Sweden Democrats were first elected to the Riksdag.

Since then, the Sweden Democrats have monopolized the position of the populist party in Sweden. Although it has occasionally been claimed that the socialist Left Party is populist, a consensus has emerged that the Sweden Democrats is the only Swedish party that unequivocally meets the criteria (Meijers & Zaslove, 2021; Rooduijn et al., 2023). Some believed the newly launched People’s List could become a new populist challenger. The movement, which adamantly rejected the designation of being a party, was founded just over a month prior to the election by a former Social Democratic MP known for winning a reality TV show and a sitting MEP from the Christian Democrats who had been removed from the party’s list. With decent name recognition, the People’s List initially received significant media attention. Interest quickly waned, and with only 0.6% of the votes, the People’s List is destined to become a small footnote in Swedish party history. The initiators announced shortly after the election that they would not continue their involvement with the movement (Rogvall & Nordenskiöld, 2024).

As the only relevant populist party, this article thus focuses on the Sweden Democrats. The party was founded by outright racist groups with neo-Nazi links (Larsson & Ekman, 2001). Because of this history, the party was completely shut out from co-operation with other parties on the national stage for many years due to a cordon sanitaire. This began to change before the 2018 election and, more explicitly, before the 2022 parliamentary election, when three of the centre-right parties expressed a more open stance towards the Sweden Democrats (Bolin et al., 2023). Despite an election outcome in 2022 where these parties lost ground, they managed, with the support of the Sweden Democrats, to regain control of the government after eight years of Social Democratic-led rule. With 20.5% of the votes as the country’s now second-largest party, the Sweden Democrats’ support was crucial for the new government. The party was also rewarded through a far-reaching co-operation agreement. Many observers suggested that the Sweden Democrats had significant influence over the agreement (Aylott & Bolin, 2023). The 2024 European Parliament election was thus the first election in which the Sweden Democrats participated while having formal influence over the government, serving as a potential test of how voters viewed the party’s collaboration with former adversaries from the establishment.

The party’s political profile and priorities resemble those of other parties in the populist radical right family (e.g., Jungar & Jupskås, 2014). Its main priorities have been a restrictive immigration policy and a tough stance on crime. Regarding the EU, the party long favoured exiting the EU. However, following the aftermath of Brexit and a surge in pro-EU attitudes among the electorate, the party moderated its criticism. Prior to the 2019 European Parliament election, the party dropped its demand for a referendum on EU withdrawal (Bolin, 2023a). Despite abandoning its hard Eurosceptic position, it remains the most EU-sceptical party in Sweden, possibly alongside the Left Party.

A key issue, similar to those faced by comparable parties in other EU countries, is the party’s stance on Russia. Despite having taken a stance against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, other parties in Sweden have accused the Sweden Democrats of having an ambiguous attitude towards the Russian regime. Such attacks have not prevented the party from adopting, in turn, a critical stance towards several other similar parties, primarily within the Identity and Democracy (ID) group, precisely because they have shown a more openly friendly attitude towards the Putin regime (Bolin, 2023b).

The party succeeded in entering the European Parliament for the first time in 2014. One of the most decisive issues for the party has been how the Swedish public perceives its actions at the European level. This concern is particularly evident in the party’s group affiliation in the European Parliament, as there are fears of being tainted domestically by association with other populist radical right parties with extreme pasts and reputations (McDonnell & Werner, 2018). After the 2014 election, the Sweden Democrats applied for membership in the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR) but were not accepted. Instead, it was admitted into the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD), which actively recruited MEPs from elsewhere after the Danish People’s Party left to join the more mainstream ECR (Bolin, 2015). However, a few years later, resistance to the Sweden Democrats decreased somewhat, leading the party to join its Nordic neighbours, the Danish People’s Party and the Finns Party, in the ECR just one year before the 2019 election (Johansson et al., 2024). Despite the Danish People’s Party leaving the group to join ID a few years later, the Sweden Democrats remained in the ECR for the remainder of the parliamentary term.

The election campaign

Over time, the Sweden Democrats have built up a highly effective communications department that has successfully attracted media and public attention. The communication has often been controversial. In a TV advertisement ahead of the 2010 election, for example, the party illustrated the need for economic prioritization by showing a group of niqab-clad women with strollers racing against an elderly woman with a walker to reach the benefit payment first (Bolin et al., 2022). And in 2020, when party leader Jimmie Åkesson travelled to the border between Turkey and Greece, he distributed flyers with the text ‘Sweden is full’ (Fridolfsson & Elander, 2021).

The campaign strategy in the 2024 European Parliament election initially followed previous patterns. A year before the election, the party leadership proposed a ‘referendum lock’, a law stipulating that all major transfers of power and demands for larger payments to the EU must first be approved in a referendum (Åkesson & Weimers, 2024). This move was seen by many as a way to assert the party’s position as the most EU-sceptical. The campaign continued to be characterized by opposition to further transfers of power to the EU. However, the main focus was consistently related to immigration, often with connections to crime. The party invested heavily in the slogan ‘My Europe builds walls’, a paraphrase of the former Social Democratic Prime Minister Stefan Löfven’s statement during the 2015 refugee crisis that ‘My Europe does not build walls.’ The message appeared on the party’s campaign posters and YouTube channel, where it was accompanied by various dramatic videos showing people with seemingly foreign backgrounds engaging in violent protests or otherwise behaving in a disturbing manner. The message was clear: immigration creates problems, so Sweden and Europe need to close their borders.

The campaign initially had the intended effect of creating media attention around the party. The election campaign soon took a new turn when, about a month before the election, it was revealed that the party’s communications department hosted a so-called troll factory, where anonymous social media accounts spread disinformation and derogatory portrayals of other politicians. The revelation was condemned unanimously by all other parties, including those in the government that the Sweden Democrats were co-operating with. The party responded with a strong counterattack through a five-minute ‘speech to the nation’ on YouTube, where Åkesson claimed that the reporting and the following reactions were ‘a massive domestic influence operation by the collective left–liberal establishment’ (Sverigedemokraterna, 2024). Given the Sweden Democrats’ conventional approach of handling troublesome revelations by downplaying or ignoring the accusations, many were surprised by Åkesson’s strong counterattack. After the election, reports also emerged of rare internal criticism regarding how the party leadership handled the situation. It is plausible that the party’s handling of the crisis also contributed to some voters refraining from voting for the party.

Possibly facilitated by the party’s increased confidence after being given formal influence for the first time, there were also tendencies to express certain controversial positions more openly than before. The party was, for example, once again criticized for its stance on Russia. This recurring discussion was reignited after Åkesson stated that there is an upper limit to how much support Sweden should give to Ukraine (Carlsson, 2024) and, perhaps even more so, after the party’s top candidate, Charlie Weimers, suggested that their own party group, ECR, should be open to co-operating with parties in the ID group, whose stance on Russia has been characterized as relatively friendly (Nordenskiöld, 2024).

Åkesson also received criticism when, just days before the election, he claimed in an opinion piece that multiculturalism had led to a population replacement in Sweden (Åkesson, 2024). A reference akin to the well-known ‘Great Replacement’ theory within right-wing extremist and conspiratorial circles (Mudde, 2019), despite Åkesson himself having distanced himself from the concept just a year before the election.

The ‘demand side’ of populism

Unlike many other populist radical right parties, the Sweden Democrats failed to make gains in the 2024 European Parliament elections. As illustrated in Figure 1, this is an exceptional occurrence since the party had never previously lost ground compared to a preceding national election. Despite securing 13.2% of the votes and retaining its three MEPs, the party experienced a decline of just over 2 percentage points compared to the 2019 election. The contrast with the 2022 national parliamentary election, the Riksdag, underscores the magnitude of this setback.

The Sweden Democrats usually perform worse in the European Parliament elections than in the Riksdag elections. But even taking this into account, the result must be seen as a disappointment, especially since pre-election polls indicated a clear success for the party. Before the election, the question was whether the Sweden Democrats would succeed in becoming the country’s second-largest party. The images broadcast from the party’s election night event, when the exit poll results indicated that they had not only failed to surpass the Moderates but had also been overtaken by the Green Party, were almost of a party in shock.

Turning to the question of who voted for the party based on the exit poll (SVT, 2024), no major surprises emerge. The sociodemographic patterns from previous elections reappear. While 18% of men voted for the Sweden Democrats, only 9% of women did so—at the voter level, the Sweden Democrats are as many other similar parties still männerparteien (Harteveld et al., 2015). Age-wise, there is no clear profile even though the party performs relatively well among the youngest voters (18–21 years old), much like in the parliamentary election of 2022. The party is overrepresented among the unemployed (20%) and those receiving sickness or disability benefits (24%). The party’s voters are also relatively strong among those with the lowest education levels. Additionally, the party is underrepresented among voters who grew up outside Sweden. The relatively low voter turnout of 53.4%, a decrease of nearly 2 percentage points since 2019, and the fact that the party is overrepresented in some of the groups that typically vote to a lesser extent provide some indication of why the Sweden Democrats did not perform as well as it did in the 2022 parliamentary election.

Additional clues are given if we focus on voter mobilization and issue prioritization. It appears that the Sweden Democrats failed to mobilize their supporters to the polls. The party stands out from the others in that it had the highest proportion of voters (59 % compared to the average of 38%) who had decided which party to vote for before the start of the election campaign. Consequently, the party performed the worst relatively in mobilizing voters in the week leading up to the election (23% compared to the average of 40%). The impression that the party failed to convince its supporters to turn out is strengthened by the fact that the proportion of voters who actually voted for the party was similar to those who said they would vote for the party if there were a parliamentary election today, while other opinion polls on voting intentions for the Riksdag, both shortly before and shortly after the election, showed significantly higher support for the party. So rather than switching to other parties, some Sweden Democrats sympathizers chose to abstain from voting.

The fact that the party supports the incumbent government might partially explain the problem of mobilizing voters. However, the aforementioned troll factory scandal is likely a more plausible partial explanation for why some voters chose to stay home. Even more likely, it was an agenda effect. While crime prevention, one of the party’s more important issues, was just as important to voters in 2024 as it was in the 2019 European election, the party’s main issue, ‘refugees/immigration’, was less significant than it had been in both the previous European election and the Riksdag election of 2022. In the exit poll, it was only ranked 11 out of 17 when voters were asked about the importance they attributed to different issues in their choice of party. Only 36% of voters indicated that this issue was of very great importance, which can be compared to 67% for ‘peace in Europe’, 60% for ‘democracy in the EU’, and 53% for ‘climate’, issues not highly prioritized by the Sweden Democrats.

Similarly, the issue of ‘national independence’, closely related to the Sweden Democrats’ message of resistance to transferring more power to Brussels, decreased somewhat compared to the 2019 election and ranked low on voters’ priority list. At the same time, the party’s positioning as the most EU-sceptical seems to resonate with voters. Among respondents who want Sweden to leave the EU, a significant 54% voted for the Sweden Democrats, compared to 11% for the Left Party, the second Eurosceptic party. The survey also confirms that the European Parliament election is primarily a domestic issue for Sweden Democrats voters. 59% of the party’s voters stated that the Sweden Democrats’ efforts in Swedish politics were very important in their choice of party. The corresponding figure for other parties varied between 19 and 46%.

Implications for the future

The 2024 EP election was a serious blow to the self-image of the Sweden Democrats as the eternal election winners. The result was surprising. However, there is no overwhelming evidence that this is the beginning of the end. Rather, it is reasonable to consider the vote decline as an indication that the party will now face ups and downs like most other parties. Moreover, in many respects, the election took place during a perfect storm that resulted in the party’s underperformance. The political agenda was dominated by issues not prioritized by the Sweden Democrats. The troll factory revelations also overshadowed the campaign and, perhaps even more importantly, how the party mishandled this crisis. In addition, and most likely due to this mishandling, many potential voters opted for abstention.

For the Sweden Democrats, European elections are still second-order elections. What happens in European Parliament elections and in Brussels is important primarily insofar as it has repercussions on their reputation at home. Despite harsh condemnations from the Swedish government parties following the troll factory revelations, they seemed equally inclined to move on. After all, the government parties are entirely dependent on the support of the Sweden Democrats for their continued survival. Despite the electoral defeat in the European Parliament election, it is important to note that the party still holds three seats in the EP. Most likely, these will be used strategically to join the group that offers the best leverage for their domestic agenda. The party will continue to maintain its position as the most EU-sceptical party in Sweden and express opposition to further transfers of power and money to the EU. At least for now, the most reasonable interpretation of the party’s election results seems to be more of a temporary speed bump in the road rather than the start of an uphill journey.

(*) Niklas Bolin is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden. His main research interests include parties and elections, with a specific focus on party organization, leadership, intra-party democracy, youth wings and radical right parties. He has published in high-ranking international journals, including the Journal of Common Market Studies, Party Politics and West European Politics. E-mail: niklas.bolin@miun.se

References

Åkesson, J. (2024, 3 June). Man kan hävda att det pågår ett folkutbyte. Expressen. https://www.expressen.se/debatt/man-kan-havda-att-det-pagar-ett-folkutbyte/

Åkesson, J., & Weimers, C. (2024, 15 May). Hög tid för en ny svensk EU-strategi. Svenska Dagbladet,https://www.svd.se/a/veb1QB/sd-hog-tid-for-en-ny-svensk-eu-strategi

Aylott, N., & Bolin, N. (2023). A New Right: The Swedish Parliamentary Election of September 2022 West European Politics, 46(5), 1049-1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2156199

Bolin, N. (2015). A Loyal Rookie? The Sweden Democrats’ First Year in the European Parliament. The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 11(2), 59-77.

Bolin, N. (2023a). Continued Absence: A Case Study of EU Salience in the Swedish Parliamentary Election of 2022. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(S1), 102-114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13529

Bolin, N. (2023b). The repercussions of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the populist Radical Right in Sweden. In G. Ivaldi & E. Zankina (Eds.), The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-wing Populism in Europe (pp. 303-313). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0031

Bolin, N., Dahlberg, S., & Blombäck, S. (2023). The stigmatisation effect of the radical right on voters’ assessment of political proposals. West European Politics, 46(1), 100-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.2019977

Bolin, N., Grusell, M., & Nord, L. (2022). Politik är att vinna. De svenska partiernas valkampanjer. Timbro förlag.

Carlsson, A. (2024, 28 April). Åkesson: “Finns en övre gräns för Ukrainastöd”. Göteborgs-Posten. https://www.gp.se/politik/akesson-finns-en-ovre-grans-for-ukrainastod.355a90bd-2c27-47af-9133-754ada2af39a

Fridolfsson, C., & Elander, I. (2021). Between Securitization and Counter-Securitization: Church of Sweden Opposing the Turn of Swedish Government Migration Policy. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 22(1), 40-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2021.1877671

Harteveld, E., Van Der Brug, W., Dahlberg, S., & Kokkonen, A. (2015). The gender gap in populist radical-right voting: examining the demand side in Western and Eastern Europe. Patterns of Prejudice, 49(1-2), 103-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2015.1024399

Johansson, K. M., Jungar, A.-C., & Jupskås, A. R. (2024). The transnational dimension of the Nordic populist radical right. In A.-C. Jungar (Ed.), The Nordic Populist Radical Right. Voters, Ideology, and Political Interactions. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429199936

Jungar, A.-C., & Jupskås, A. R. (2014). Populist Radical Right Parties in the Nordic Region: A New and Distinct Party Family? Scandinavian Political Studies, 37(3), 215-238. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12024

Larsson, S., & Ekman, M. (2001). Sverigedemokraterna. Den nationella rörelsen. Ordfront.

McDonnell, D., & Werner, A. (2018). Respectable radicals: why some radical right parties in the European Parliament forsake policy congruence. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(5), 747-763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1298659

Meijers, M. J., & Zaslove, A. (2021). Measuring Populism in Political Parties: Appraisal of a New Approach. Comparative Political Studies, 54(2), 372-407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020938081

Mudde, C. (2019). The far right today. Polity Press.

Nordenskiöld, T. (2024, May 31). SD redo för samarbete med ryssvänliga partier. Expressen.

Rogvall, F., & Nordenskiöld, T. (2024, 27 June). Jan Emanuel lägger ner Folklistan – har sökt medlemskap i Socialdemokraterna. Expressen. https://www.expressen.se/nyheter/sverige/jan-emanuel-har-sokt-om-medlemskap-i-s-igen/

Rooduijn, M., Pirro, A. L. P., Halikiopoulou, D., Froio, C., Van Kessel, S., De Lange, S. L., Mudde, C., & Taggart, P. (2023). The PopuList: A Database of Populist, Far-Left, and Far-Right Parties Using Expert-Informed Qualitative Comparative Classification (EiQCC). British Journal of Political Science, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000431

Sverigedemokraterna. (2024). Jimmie Åkessons tal till nationen. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mfQnKHlvEzE

SVT. (2024). SVT:s vallokalsundersökning EUP-valet 2024. https://omoss.svt.se/download/18.273015e218fe7d3833535561/1718110247331/ValuResultat_EUval_2024.pdf

Vinocur, N. (2024, June 6). As Europe votes, a populist wave surges. Politico Europe,https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-election-vote-populist-wave-alternative-for-germany-national-rally/

Vohra, A. (2024, March 13). A Far-Right Takeover of Europe Is Underway. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/03/13/eu-parliament-elections-populism-far-right/