In this timely and thought-provoking interview, Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi explores how authoritarianism has become “the new normal” in the Middle East amid a global retreat from democratic norms. Speaking to the ECPS, Dr. Al-Marashi analyzes the region’s complex landscape shaped by imperial legacies, resource politics, and shifting global alliances. He highlights how populist rhetoric, digital platforms, and transactional diplomacy—especially under Trump-era politics—are empowering authoritarian leaders and weakening democratic institutions. While civil society faces mounting repression, Dr. Al-Marashi suggests that digital activism and “artivism” may offer spaces of survival and resistance. This interview provides essential insight into how populism and authoritarianism intersect in the Middle East—and what that means for the future of governance in the region.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In an era marked by the erosion of liberal democratic norms and the global resurgence of authoritarian tendencies, Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi—Associate Professor at Department of History, California State University, San Marcos—offers a timely and incisive analysis of the Middle East’s evolving political landscape. In an in-depth interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Al-Marashi argues that “authoritarianism has become normalized—it’s now the prevailing norm,” particularly in a world increasingly shaped by populist and transactional leadership.

Drawing from historical legacies and contemporary global shifts, Dr. Al-Marashi underscores how imperial interference and resource wealth have long laid the groundwork for authoritarian populism in the region. “Hydrocarbons enable political elites to generate revenue without relying on taxation,” he explains, allowing regimes to distribute wealth in ways that bypass democratic accountability and reinforce autocratic control. He connects this dynamic to broader regional patterns, noting that even militant groups such as ISIS have employed populist strategies by attempting to dismantle colonial-era borders and mobilize transnational support.

Dr. Al-Marashi highlights the impact of shifting global power dynamics, particularly the rise of multipolarity and the influence of Trumpism, in undermining democratic aspirations. With the US retreating from its rhetorical commitment to democracy, populist-authoritarian leaders find renewed legitimacy. “If the US is adopting these behaviors,” he argues, “this is the new norm—this is the future.” This sets a precedent for regimes that increasingly embrace personalistic and sultanistic rule, with little concern for liberal democratic values.

Transactional diplomacy, particularly under Trump, has also reshaped regional alliances. Dr. Al-Marashi notes that such diplomacy empowers authoritarian actors like Netanyahu, while simultaneously emboldening sectarian militias and weakening traditional state structures. “It’s a double-edged sword—quite literally,” he remarks, especially when it comes to balancing regional power plays and proxy conflicts in places like Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

While the picture appears bleak, Dr. Al-Marashi also points to the resilience of digital resistance. He suggests that civil society and democratizing efforts may survive—if not flourish—through digital activism and what he terms “artivism.” In a region where the state has often failed to provide basic services, digital spaces may serve as the last frontier for democratic imagination and mobilization.

This interview captures the complexity of a region grappling with entrenched authoritarianism amid a globally permissive environment—and offers critical insights into how populist movements and power politics intersect in the 21st century Middle East.

Here is the lightly edited transcript of the interview with Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi.

Imperial Legacies and Oil Wealth Laid the Foundation for Authoritarian Populism in the Middle East

Professor Ibrahim Al-Marashi, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: What historical and socio-political conditions in Iraq and the broader Middle East have laid the groundwork for the rise of populist authoritarianism in the region?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: The obvious factors are imperial interference and hydrocarbons—oil and gas. The involvement of foreign powers, whether Britain or the US, consistently provides a convenient enemy to rally against. Meanwhile, hydrocarbons enable political elites to generate revenue without relying on taxation. This, in turn, enhances populism, as the revenues can be distributed directly through large-scale projects that bolster support for figures like Saddam Hussein—or any other authoritarian leader—not only in Iraq but across the region.

How have legacies of colonialism, militarization, and post-conflict governance contributed to the entrenchment of populist and authoritarian leadership styles in the Middle East?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: In the case of Iraq, the British were always a convenient target to rally against. In other states ruled by France, for example, populations could similarly rally against the legacy of the colonial power. Even if you look at ISIS as a kind of populist and terrorist group, its goal of dismantling borders was an attempt to mobilize the masses—not just in the Middle East, but across the entire Muslim world. Saddam Hussein framed the invasion of Kuwait as an effort to erase borders established by British colonialism, making it a similarly convenient rallying point. And then, let’s not forget the United States. In the case of the Houthis, for instance, their appeal extends not only beyond Yemen but throughout the region, as they are perceived as one of the last groups seeking agency in a region largely shaped by US control. This is the legacy: there are concrete historical borders that have divided communities, but there is also, in the collective imagination, a persistent target around which to rally.

Authoritarianism Has Become the New Norm—This Is the Future

From a populism perspective, how are shifting global power dynamics — especially the rise of multipolarity and the return of a nationalist, transactional Trump administration — shaping authoritarian resilience and weakening democratic aspirations in the Middle East? In what ways might these trends bolster authoritarian populist movements across the region?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: Authoritarianism has become normalized—it’s now the prevailing norm. Even though the US has often behaved in authoritarian ways, it at least used to pay lip service to the promotion of democratic governance around the world. I think that facade has now been abandoned. As a result, populist leaders can more or less say, “Look, if the US is adopting these behaviors, this is the new norm—this is the future.”

Even in the case of Russia, there appears to be, at the very least, a personalistic rapprochement—a relationship based more on the closeness of individual leaders than shared values. The emerging regime type in this multipolar world is personalistic—what you might call sultanistic—drawing on the term “Sultan,” as used by the academic Houchang Chehabi.

If that’s the case, then there is no longer a democratic model to aspire to. This increasingly looks like the wave of the future—the future of governance.

How has the populist rhetoric of the Trump administrations—particularly their framing of “radical Islam” and their regional double standards—impacted the legitimacy of state institutions and non-state actors in Iraq and the broader Middle East?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: In this case, there are two dynamics at play. This ties back to your earlier question about transactional foreign policy. If Trump makes a deal with Iran over its nuclear program—well, the Iraqi Shia militias are essentially mass mobilization forces for the Shia population, and much of that mobilization is supported by Iran. If Iran enters negotiations with the US, it would have less incentive to continue backing those militias. That’s one example involving non-state actors.

Then there’s the other paradox: an escalation of the war against the Houthis in Yemen. Iran might choose to rein them in, but if not, the Houthis may continue attacking Red Sea shipping as a consequence of these ongoing tensions. This illustrates how transactionalism, populism, and non-state actors intersect in the region.

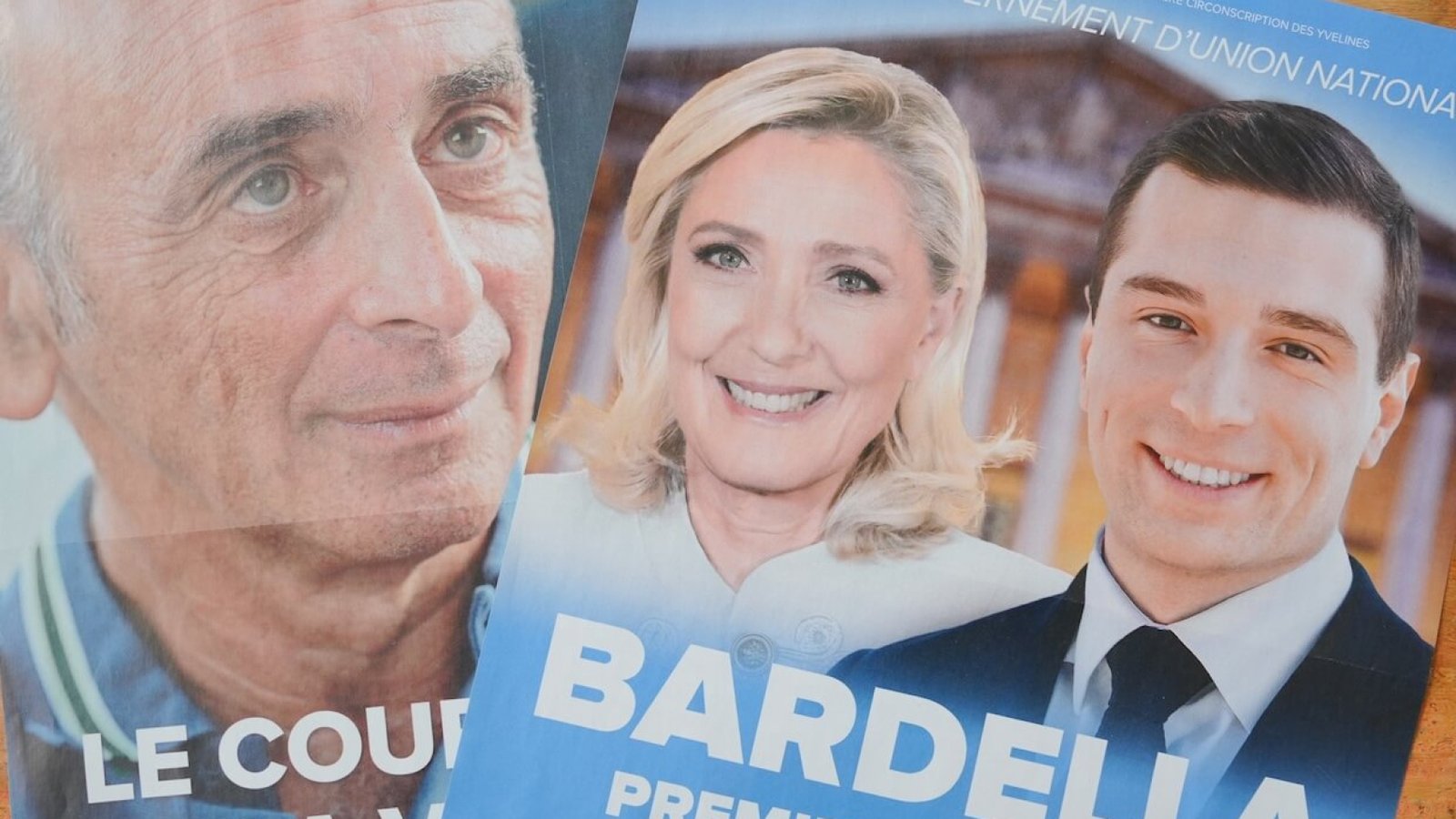

Transactional Diplomacy Fuels Sectarian Populism

Photo: Ibrahim Khader / Pacific Press.

Could the Trump administration’s emphasis on transactional diplomacy further embolden sectarian and ethnic populism in conflict zones like Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and how?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: Not okay—on two levels. Transactional diplomacy with Netanyahu might embolden him to act unilaterally in Syria and Lebanon, and perhaps even as far as Yemen. Israel’s actions in these areas could fuel sectarianism in several ways: it could lead to a resurgence of Hezbollah in Lebanon, embolden the Houthis, and prompt Israel to use the Syrian Druze minority as a proxy. That’s one pathway through which sectarianism might be intensified.

Israel might also be emboldened to target Iraq’s Shia militias, which are part of the so-called “axis of resistance.”

On the other hand, if this transactional diplomacy were to result in a grand bargain with Iran, those same actors might be reined in.

So it’s a double-edged sword—quite literally—in terms of how this foreign policy could shape the region.

In your view, how does the militarization of politics via militias such as The Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) reflect populist strategies of political mobilization in the Middle East, especially in terms of bypassing traditional democratic institutions and appealing to ‘the people’?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: The PMU is really a broad body of militias. A good number of them first emerged to resist the US occupation of Iraq. Initially, I don’t think it was about bypassing democratic institutions. Many were mobilized because Ayatollah Sistani was able to rally the masses in response to the ISIS threat.

The way they later contributed to undermining institutions in Iraq was by becoming a parallel force to the Iraqi military, and eventually by playing a role against the protests that called for better governance and technocratic rule.

So it’s complicated. The Popular Mobilization Units emerged in response to the occupation, later served as Iranian proxies, then fought against ISIS, and eventually remained as a force that prevented the Iraqi military from maintaining a monopoly on violence—borrowing from Max Weber’s concept.

Again, we’re at an inflection point. I think it all hinges on a potential deal with Iran: whether these militias will be reined in and subsumed into the army or the security sector, or whether they will continue to act as spoilers to Iraq’s post-conflict governance structure.

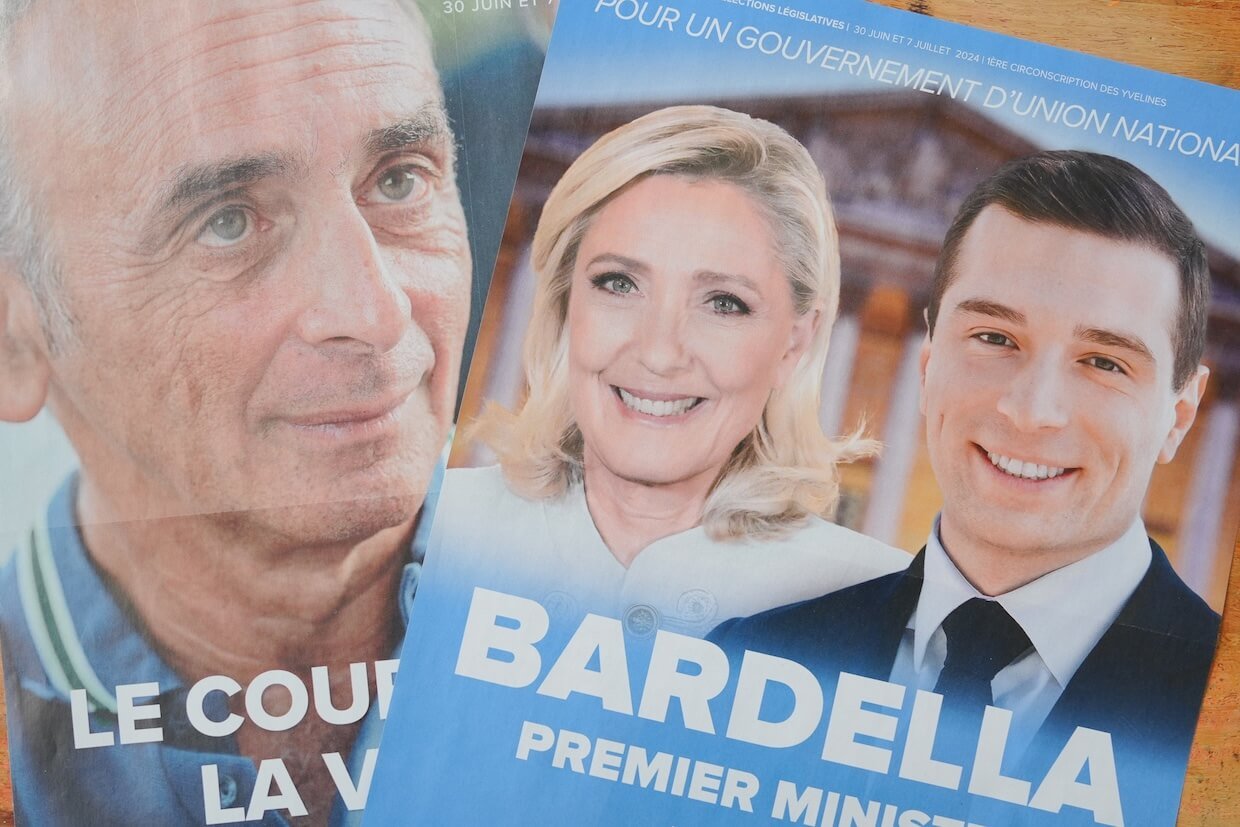

When the State Fails, Militias Become the Security Provider

Photo: Nabil Kassir.

Considering your work on COVID-19 and militia reinvention, how do crises (like pandemics or conflicts) serve as opportunities for populist-authoritarian actors in the Middle East to entrench power under the guise of serving ‘the people’—and how might this intensify under a second Trump presidency?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: Take the case of the pandemic—and I’ll give you an example closer to home, where I am in San Diego. When COVID hit Mexico, you had drug cartels, like those formerly under Guzmán (El Chapo), distributing medical kits—such as masks and water—to people affected by COVID-19. In other words, when the Mexican security sector failed and the health sector also failed, these non-state actors filled the void. They became both the security and health sectors.

That’s exactly what happened with COVID-19 in the Middle East—in places like Lebanon, Yemen, and Iraq. It was the Houthis, Hezbollah, and the Shia militias that were disinfecting public spaces, distributing masks, and so on. What these places have in common is the collapse of the security sector. As Max Weber said, when the state no longer holds a legitimate monopoly on violence, non-state actors step in and become both the security and health providers.

This is ultimately an indictment of the weak health sectors in those societies. But the weak health sector is a reflection of a weak security sector—you don’t have an army capable of enforcing the state’s monopoly on violence. When the state is unable to provide basic services—what we call biopower, the ability to keep the population alive—you get necropolitics instead. That’s when the state is too weak to deliver health services, and violent non-state actors—cartels or militias—step in to fill the void.

How do Middle Eastern regimes employ especially Islamist populist rhetoric domestically to justify authoritarian practices, especially in an international environment increasingly tolerant of illiberal governance?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: Islamist rhetoric is by definition an attempt to mobilize the masses through faith. When governance fails, you turn to divine governance to justify authority and appeal to the imagination. That’s how I would see it. It’s similar to using anti-colonial rhetoric—it’s more or less an appeal to the masses. When the public has very little faith in the structures that govern them, this is where Islamist rhetoric steps in to fill the gap.

Every Power Is Backing Proxies—Democracy Is No Longer the Goal

What role do you foresee for regional actors (such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey) playing in either reinforcing authoritarianism or providing openings for democratic movements under these new global conditions?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: You know, in that regional mix, I would also add Israel—and this is a post-October 7th development. I’ll tell you why. In 2011, during the Arab Spring, for the first time in the region’s history, the US more or less refrained from intervening in the fate of regimes. It allowed the regime of Hosni Mubarak, a longtime ally, to fall. In that vacuum, Saudi Arabia and Iran engaged in a regional cold war, with Turkey also entering the mix. It became, in effect, a three-way conflict.

What followed was a regional cold war accompanied by counter-revolutionary dynamics. One of those counter-revolutionary tendencies eventually prevailed. Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia each chose sides—supporting different counter-revolutionary or revisionist forces. These rivalries played out through proxy conflicts.

Now, after October 7th, Israel has entered the fray.

So the region today looks very different from the era of Arab Spring optimism. Every major power is backing proxies to serve its own interests. And this is especially evident in Syria.

If you want to understand how four actors are shaping Syria’s future: Turkey is deeply invested in the current Syrian government; Israel is working to expand its presence; Saudi Arabia is wiping away Syria’s debts; and Iran is trying to preserve the influence it has lost. None of these four powers are interested in a transition to democratic governance in Syria. All are focused on maintaining their respective spheres of influence. In that sense, each is likely to reinforce autocratic tendencies. They are more inclined to back warlords as proxies than to support any meaningful democratic transition.

Given the historical reliance of Middle Eastern authoritarian regimes on external patrons, how might a US foreign policy under Trump 2.0 reshape alliances, especially with regimes facing internal legitimacy crises?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: I think the best case in point is how close the Trump administration was to Saudi Arabia. So it might try, in a second term, a strategy of offshore balancing—essentially carving out spheres of influence in a multipolar system and telling Saudi Arabia: “We’re not really concerned about your human rights issues, but you maintain order in the Gulf.”

The US would provide as many weapons as needed, and of course, Trump would say, “You have to pay for them,” to boost his standing domestically. But the message would be: it’s your job to be the policeman in the Gulf. That’s what I mean by offshore balancing.

The same approach would likely apply to Israel. That doesn’t bode well for the future of Palestinian governance, and Saudi Arabia would have little incentive to address human rights issues—as long as it continues to receive a blank check from Washington.

Authoritarianism Is Not Just Tolerated—The Masses Are Seen to Want It

Could the erosion of liberal democratic norms in the West, accelerated by populist leaders like Trump, provide ideological “cover” for Middle Eastern populist-authoritarian leaders? How?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: Absolutely—especially now that the US doesn’t even go through the motions of paying lip service to human rights.

From the perspective of international relations theory—specifically constructivism—a new norm has been constructed: not only can authoritarian governance be tolerated, but the masses actually want it. It’s no accident that the masses elected someone like Trump. Or, to go further, take the case of El Salvador—you have another kind of authoritarian-populist leader who is more or less aligned with the Trump administration’s approach.

And I think that’s become a model for the rest of the world. Regimes can now say: not only does the US want strongman leadership, but you—the people—want it too. Because a strong hand gets things done.

In what ways might regional populist movements exploit global discourses of “national sovereignty” and “anti-globalism,” championed by Trumpism, to consolidate authoritarian rule?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: When you talk about discourses and global dynamics, there’s an important element here called digital populism. All of this is enabled because politics now also occurs on a digital plane. More or less, digital platforms have become a way for authoritarian regimes to bypass traditional media structures and appeal directly to the masses—especially in cases where traditional media has not yet been fully co-opted by authoritarian leaders. So, to answer your question, digital populism is the key. It’s the mechanism through which these discourses become normalized and reach mass audiences.

Exclusion, Not Sectarianism, Is the Real Threat

Given the weakening of traditional international pressure for democratization, do you foresee populist movements in the Middle East mutating toward more overt forms of sectarianism, ethno-nationalism, or exclusionary politics?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: I would say more toward exclusionary politics. And here’s why: if we look at this in terms of ethno-sectarianism, I wonder if the region has been exhausted by those challenges. Let me explain what I mean. At one point, the so-called “axis of resistance” included Persian Twelver Shia Iran; Arab Twelver Shia militias in Iraq; an Arab Alawite regime in Syria; Arab Twelver Shia Hezbollah; Zaydi Shia Houthis in Yemen; and Arab Sunni Islamist groups like Islamic Jihad and Hamas. Of course, that axis of resistance has been dealt a very heavy blow in recent years. But the fact that such an ideologically diverse coalition could form makes me question whether the ethno-sectarian frame has been over-fetishized. There are other, more complex realities on the ground.

I think ethnic and sectarian identities are securitized—that is, they are instrumentalized when convenient for those in power, and then abandoned when such divisions no longer serve political interests. So, if that’s the case, I see the trajectory more in terms of exclusionary politics. Populism becomes a mask to mobilize the masses—but always at the expense of issue-based politics and inclusive governance. Those who are excluded often include civil society actors, journalists, and ethnic minorities, for example.

In a context where Western powers show declining interest in promoting democracy abroad, is there still space for bottom-up democratization efforts in the Middle East, or are we entering a phase of entrenched authoritarianism?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive. We are indeed facing entrenched authoritarianism, but I would also say—thinking back to digital populism—that if authoritarianism is being entrenched through digital means, then perhaps bottom-up approaches can also survive through digital spaces.

I’m thinking, for example, of the digital hacktivist collective Anonymous. During the Arab Spring, when various regimes tried to crush protests, Anonymous hacked into state systems in support of the protesters. That’s just one example.

Because, of course, ideas can’t be killed, right? And the one sphere that hasn’t been fully subsumed by the state is still the digital realm. I think that’s where these democratic ideas and efforts can continue to exist.

Does that necessarily translate into on-the-ground resistance? That has yet to be seen. But at this particular inflection point, I believe that’s where the ideas will, at the very least, find refuge.

If Silence Is Spreading in the US, Imagine How Much Worse It Is in the Middle East

And finally, Professor Al-Marashi, considering the weakening of global democratic norms, how can civil society actors in the Middle East adapt their strategies for resistance and survival amid a more authoritarian-friendly international environment?

Dr. Ibrahim Al-Marashi: Again, I refer to my previous answer. I think, at the end of the day, these groups might survive digitally. They’ll be able to organize online. But to be honest, if you look at how the region has been transformed since 2011, it does not look good. So many of these actors are barely surviving.

At the end of the day, the ideas might persist—through digital activism, through art, through artivism.

But I’m speaking from the US, where even here, the ability to speak openly—on campuses, for example—is being threatened. If I can sense a wave of silence coming here, I can only imagine how much worse it must be in the Middle East.