In his lecture at the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025, Professor Robert Huber examined how populist parties across Europe construct climate skepticism, emphasizing that populism’s “thin-centered ideology” (as defined by Cas Mudde) pits “the pure people” against “corrupt elites.” This framing makes climate science and policy institutions prime targets for populist critique. Professor Huber’s expert survey of 31 European countries showed a clear trend: the more populist a party, the more skeptical it is of climate policy and climate science, regardless of its left- or right-wing orientation. He cautioned participants to disentangle populism from related ideologies like nationalism or authoritarianism, underscoring that populism’s challenge to climate politics is complex, context-dependent, and shaped by deeper struggles over legitimacy, authority, and representation.

Reported by ECPS Staff

The ninth lecture of the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025, titled “Populism and Climate Change: Understanding What Is at Stake and Crafting Policy Suggestions for Stakeholders,” was held online from July 7 to 11, 2025. On Friday, July 11, Professor Robert Huber delivered his lecture on “Populist Narratives on Sustainability, Energy Resources and Climate Change,” offering participants a rigorous exploration of the complex intersections between populist politics and climate discourse.

The Summer School convened scholars, students, and practitioners from around the world to engage in critical discussions about how populism shapes—and is shaped by—the politics of climate change. It provided a unique interdisciplinary forum to analyze these global dynamics and to develop policy-relevant insights for stakeholders navigating the overlapping crises of climate and democracy.

The session was moderated by Dr. Susana Batel, Assistant Researcher and Invited Lecturer at the University Institute of Lisbon’s Center for Psychological Research and Social Intervention. Dr. Batel’s own research focuses on the green transition and its relationship to socio-environmental justice, exploring how climate and energy policies may reproduce or challenge entrenched social inequalities. More recently, she has turned her attention to the relationship between green transition efforts and far-right populism, particularly in Portugal. In her introduction, Dr. Batel underscored the relevance of Professor Huber’s expertise for these pressing questions, noting that his work has become central to ongoing debates on how populist actors respond to climate policies and narratives.

Dr. Robert Huber is Professor of Political Science Methods at the University of Salzburg. His research expertise lies at the intersection of populism, political methodology, and climate politics, and he has become a leading figure in the emerging field studying how populist parties and leaders engage with environmental and energy issues. As Dr. Batel observed in her remarks, Professor Huber has helped illuminate how populist actors contest not only the facts of climate change but also the legitimacy of the processes through which climate policy is made and implemented.

In his lecture, Professor Huber tackled the core question of why populists, both on the right and left, have often adopted a skeptical or adversarial stance toward climate action. He emphasized the importance of distinguishing populism from adjacent ideological forces such as nationalism, authoritarianism, or economic liberalism, arguing that only careful conceptual and empirical work can reveal the mechanisms through which populism interacts with climate skepticism. His lecture offered participants a comprehensive framework to understand the diversity of populist climate narratives, setting the stage for deeper discussion and analysis of this timely and globally significant phenomenon.

Why Populists Target Climate Issues

In his lecture, Professor Huber provided a rigorous and insightful analysis of why populist actors engage with climate issues, highlighting the complexity and nuance often overlooked in popular discussions. Professor Huber opened his talk by reflecting on the emerging nature of this research agenda, noting, “When I started studying populism and climate change back in 2016, there was not much on that—very little research and few opportunities to think about how these two pressing societal issues intersect.”His remarks underscored both the novelty of the topic and the importance of its exploration.

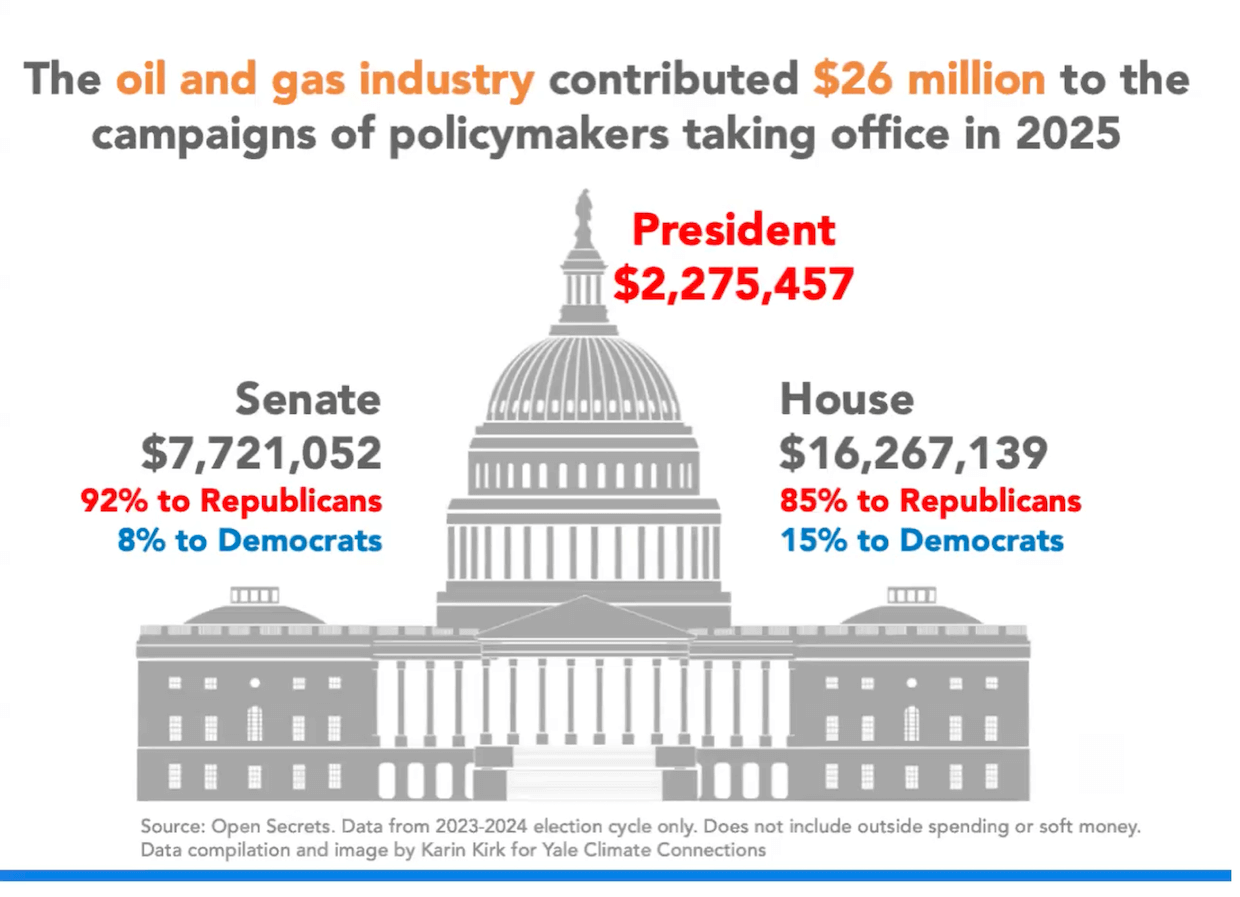

Professor Huber’s central inquiry revolved around understanding the mechanisms through which populist parties and leaders construct skepticism toward climate action. He acknowledged that figures such as Donald Trump inevitably dominate discussions of climate populism, citing one of Trump’s early tweets: “NBC News just called it the great freeze – coldest weather in years. Is our country still spending money on the GLOBAL WARMING HOAX?” While this is a classic example of conflating weather with climate, Professor Huber emphasized that such rhetoric also reflects broader concerns about public spending and government priorities.

To illustrate variation within populist climate skepticism, Professor Huber turned to European populists, including Thierry Baudet, the leader of the Dutch radical-right party Forum for Democracy. Baudet framed climate action as futile and wasteful, complaining that billions were being spent “just to decrease global warming by 0.007 degrees,” which he characterized as “madness.” Similarly, Marcel de Graaff, formerly a member of the European Parliament, attacked EU climate policy as deceitful, claiming that elites benefited financially from “green lies.” Professor Huber observed that while all three cases reflect skepticism toward climate action, they differ in emphasis—Trump’s framing centered on economic competitiveness, Baudet on policy effectiveness, and de Graaff on political betrayal.

These examples led Professor Huber to ask the central question driving his lecture: “Why is it that populist politicians are so often skeptical about climate change?” He insisted that an analytical approach is required to move beyond anecdote and description, seeking instead to understand underlying patterns and causal mechanisms.

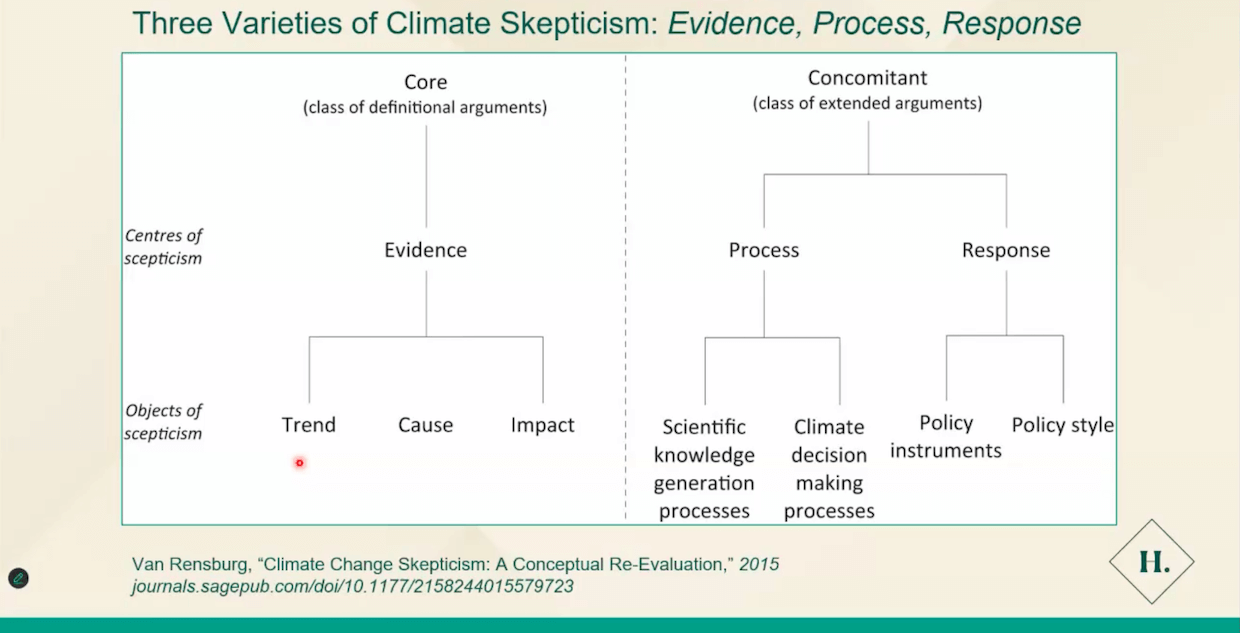

Professor Huber introduced the audience to Van Rensburg’s (2015) typology of climate skepticism, which distinguishes between skepticism about the evidence (whether climate change is real and human-caused), the process (whether decision-making and knowledge-production are legitimate), and the response (whether proposed policies are desirable). While populists may sometimes question the reality of climate change itself, Professor Huber suggested that their skepticism more often targets the process and response dimensions—expressing distrust toward scientific expertise, democratic legitimacy, and the distributive impacts of climate policy.

A particularly vivid example of this process skepticism emerged from the “Yellow Vests” protests in France, where demonstrators opposed carbon taxes not only for their economic burden but also because they perceived climate policy as undemocratic and detached from ordinary people’s needs. Professor Huber noted how one protester’s sign declared: “I want my democracy now,” reflecting the sentiment that climate decisions are made by remote technocratic elites without sufficient public input. As Professor Huber remarked, “For some people, climate policy really feels out of touch with their everyday needs.”

Professor Huber emphasized that much of this skepticism appears on the political right but cautioned against equating populism with right-wing ideology. “It may just be that they are right-wing,” he observed, highlighting that climate skepticism among populists could stem from other ideological commitments—such as nationalism, conservatism, or libertarianism—that overlap but are analytically distinct from populism itself.

Nonetheless, Professor Huber acknowledged that left-wing populism can also intersect with climate discourse in distinct ways. He pointed to emerging instances of “green populism” on the left, where actors such as Jean-Luc Mélenchon or Podemos in Spain critique climate policies for failing to address social inequalities or for being captured by corporate interests. Professor Huber explained, “Recent examples suggest that left-wing populists may foster a pro-climate populism that emphasizes social justice and corporate accountability.”

Huber structured his presentation around three guiding questions:

- What features of climate change and climate politics make them attractive targets for populist narratives?

- Are populists systematically different from non-populists in their climate attitudes?

- What recurring patterns can we identify in the narratives that populists employ when discussing climate issues?

He emphasized that populist climate skepticism should be understood as multifaceted and context-dependent. In Western Europe, outright denial of climate science (so-called “trend skepticism”) is rare; more commonly, populists challenge the legitimacy of scientific expertise, international institutions, and the distributive fairness of climate policies. Professor Huber summarized this dynamic: “What we often see is that populists are not necessarily denying climate change itself—they are contesting who makes the decisions and who pays the price.”

However, Professor Huber urged his audience to avoid conflating populism with far-right ideology and to disentangle populism’s distinctive contributions to climate skepticism from other ideological factors. He called for systematic, empirically grounded research that recognizes the diversity of populist climate narratives while remaining attentive to their common thread: a distrust of elites and a framing of climate policy as a battleground between “the pure people” and “corrupt elites.”

Theoretical Explanations for the Populism–Climate Link

Then, Professor Huber delved into the theoretical underpinnings that help explain why populist actors so often engage in climate skepticism. He posed a central question: “What is it essentially about populism that links it to climate change?” His objective was not only to describe the phenomenon but also to dissect its causal mechanisms, emphasizing the need to distinguish populism from overlapping ideologies like nationalism or authoritarianism.

Professor Huber began by outlining three principal ways of conceptualizing populism, noting that each offers different implications for understanding populist positions on climate change.

The first perspective defines populism as a political strategy. Drawing on the work of Kurt Weyland, Professor Huber explained that this approach sees populism as a mode of leadership in which a charismatic leader builds “direct, unmediated, uninstitutionalized support from large numbers of unorganized masses.” This definition, more prevalent in Latin America, highlights the personalistic and anti-institutional nature of populist movements. However, as Professor Huber observed, “this kind of definition doesn’t contain much information about how populist leaders should think about climate change,” suggesting that skepticism in this context may arise from opportunistic attempts to mobilize supporters rather than a core ideological stance.

The second conceptualization frames populism as a political style, a view associated with scholars such as Benjamin Moffitt. Here, populism is performative: it relies on provocation, transgression, and signaling difference from mainstream elites. Populists may adopt a combative tone or deliberately violate elite norms as a way of connecting with “the people.” According to Professor Huber, this style is often visible in populist climate rhetoric, where actors deny climate science not necessarily because they disbelieve it, but as a way of “demonstrating that one is different… to distance themselves from the mainstream elite.” He offered the example of Boris Johnson’s disheveled appearance as a performative signal of outsider status, adding that similar tactics are evident when populists question the legitimacy or value of climate action.

The third and most analytically productive definition, according to Professor Huber, treats populism as an ideology or a thin-centered set of ideas that divides society into two antagonistic groups: the pure people and the corrupt elites. This binary worldview, he noted, is key to understanding the climate-populism link. Populists “excel at framing politics as a struggle between good and evil,” and thus are predisposed to portray climate elites—whether scientists, international organizations, or bureaucrats—as self-serving actors imposing policies that harm ordinary citizens. As Professor Huber explained, “It’s here where we can most clearly see how populism might shape climate skepticism: elites are seen as either failing to implement climate action or doing so at the expense of the people.”

However, Professor Huber emphasized that many factors commonly associated with populism are distinct causal forces that must not be conflated with populism itself. “We often fall into the trap of saying populism and meaning the far right,” he warned, underscoring the importance of disentangling populism from other ideological dimensions such as authoritarianism, nationalism, or economic left-right positions. For example, he noted that nationalist skepticism toward international climate agreements arises not from populist anti-elitism but from a preference for national sovereignty. Similarly, authoritarian discomfort with lifestyle changes required by climate action (e.g., promoting veganism) stems from a rigid adherence to tradition, not necessarily from populist ideology.

Professor Huber also observed that left-wing populists might oppose climate policy from a different ideological position: they may view climate measures as economically regressive or damaging to the working class. Thus, left-wing and right-wing populist critiques of climate policy differ in content but share a populist framing that pits “the people” against elites.

Moreover, Professor Huber called for analytic precision in research on populism and climate politics: “We need to disentangle what is populism and what are other things that are related to populism but are not necessarily the same thing.” His careful mapping of different conceptualizations and mechanisms underscored the value of distinguishing populism from adjacent ideologies when explaining its impact on climate discourse—a message of particular relevance for scholars seeking to understand the heterogeneity of populist climate narratives.

Empirical Evidence: The Expert Survey

During his lecture, Professor Huber also presented original empirical findings from an expert survey he conducted with two colleagues across 31 European countries. The survey, fielded in 2023, sought to provide systematic insights into how populism relates to political parties’ climate positions, shifting the discussion from anecdotal observations to measurable patterns.

Professor Huber began by stressing the survey’s scope and methodology. He explained that experts—primarily political science scholars—were asked to rate the degree of populism and the climate positions of parties in their own countries. The goal was to move beyond speeches and manifestos to capture a broader and more nuanced reputational assessment of where parties stand. “This is not an absolute measure of where parties stand, but rather what experts think where this party stands,” he clarified, noting that reputational measures offer insight into parties’ perceived orientations while acknowledging their limitations in detecting recent or subtle shifts.

Populism in the survey was operationalized through a widely used definition: attitudes towards elites, attitudes towards “the people,” and belief in a unified popular will. For climate positions, the survey asked about two dimensions: (1) the extent to which parties prioritized long-term climate gains over short-term socioeconomic costs, and (2) whether parties supported a stronger role for climate science in policymaking. These two questions, he explained, were designed to tap into different aspects of skepticism: what he termed “response skepticism” (about policies) and “process skepticism”(about science and institutions).

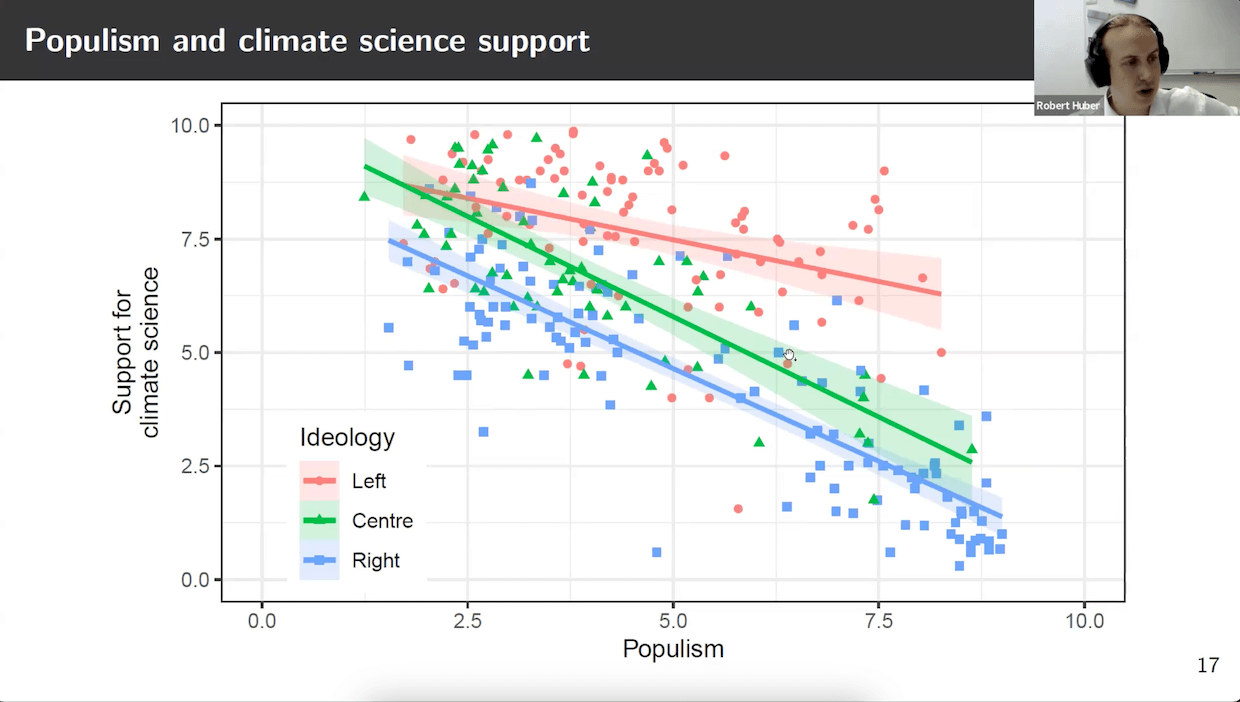

Professor Huber then turned to the findings. Presenting a scatterplot, he pointed out that “the more populist parties get, the more climate-skeptic they get in terms of not supporting climate policy.” A clear downward-sloping trend line indicated a negative relationship between degree of populism and support for climate action. This pattern was echoed when looking at parties’ support for the role of climate science: populist parties tended to express greater skepticism about scientific expertise, too.

However, a more granular analysis yielded even more striking insights. When Professor Huber divided parties into three ideological families—left, center, and right—he found that in all groups, increased populism correlated with greater climate skepticism. “What I find quite stunning,” he remarked, “and what runs a bit against this narrative of left-wing populist parties being a force for climate action, is that in all three groups we see a negative slope.” In other words, while right-wing populist parties were the most skeptical overall, even left-wing populists displayed less enthusiasm for climate action than their non-populist counterparts on the left.

This nuanced finding complicates common assumptions that left-populists are natural allies of ambitious climate policy. Professor Huber acknowledged that this pattern might partly reflect comparisons between left-populist parties and strongly pro-climate Green parties, but insisted it was a meaningful result nonetheless: “On average, left-wing populist parties are not that much more progressive when it comes to climate action than conservative or centrist parties that are not populist.”

Turning to right-wing populist parties, Professor Huber observed that these were the most skeptical of climate policy and science, but emphasized that this reflected their right-wing ideological orientation as much as their populism. “That’s not the effect of populism—that’s the effect of left-right orientation,” he cautioned, reiterating a key theme of his lecture: the need to disentangle populism from adjacent ideological factors such as authoritarianism, nationalism, or economic liberalism.

Professor Huber also reflected on the broader literature, acknowledging a “Western Europe focus” in both his own data and much existing research. He pointed out that this geographic concentration raises questions about generalizability, noting, for example, that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi represents a case that does not fit typical European populist patterns.

To illustrate how populist narratives manifest in practice, Professor Huber concluded by revisiting some familiar and varied examples. Tweets by Donald Trump highlighted skepticism framed around economic competitiveness and confusion between weather and climate. French Yellow Vest protesters exemplified resistance to climate policies perceived as unfair to working-class citizens, captured in the now-famous phrase “end of the world vs. end of the month.” Meanwhile, left-wing populists like Bernie Sanders and Spain’s Podemos criticized elites for blocking strong climate action—what Professor Huber termed “pro-climate populist frames.” However, he cautioned that such pro-climate populism remains relatively rare empirically. “Empirically, as the expert survey data shows, we don’t see this that often—it seems to be more isolated,” he concluded.

Professor Huber’s closing reflections emphasized the complexity of the populism-climate relationship. Populism’s “thin-centered” nature allows it to take multiple forms—right, left, pro-climate, or anti-climate—depending on context and adjacent ideologies. The task for scholars, he urged, is to avoid simplistic conflations and instead carefully disentangle the multiple drivers behind populist parties’ climate positions: “There is a lot of variation, and we need to systematically analyze this and disentangle the different underlying reasons for these narratives and frames.”

Conclusion

Professor Robert Huber’s lecture offered participants of the ECPS Academy Summer School 2025 a deeply analytical and empirically grounded understanding of the complex relationship between populism and climate politics. His key contribution was to disentangle populism from adjacent ideologies—such as nationalism, authoritarianism, and economic left-right positioning—insisting on analytical precision when examining why populist actors often exhibit climate skepticism.

Importantly, drawing on the work of Cas Mudde, Professor Huber distinguished populism as a “thin-centered ideology” that frames politics as a moral struggle between the “pure people” and “corrupt elites,” providing fertile ground for contesting the legitimacy of climate science, policy processes, and institutions. Populism’s anti-elitist orientation predisposes it to target those perceived as technocratic or detached from “the people,” such as climate scientists, international organizations, and bureaucratic policymakers. However, as Professor Huber emphasized, this predisposition manifests differently depending on ideological context: while right-wing populists typically reject climate action as a threat to national sovereignty, tradition, or economic competitiveness, left-wing populists may frame climate policy as failing to address social justice concerns or as captured by corporate elites.

Professor Huber’s empirical findings, drawn from an original expert survey spanning 31 European countries, provided systematic evidence that higher degrees of populism correlate with greater climate skepticism across left, center, and right ideological groups—a pattern that challenges assumptions that left-wing populism is inherently pro-climate. His analysis revealed that while right-wing populist parties are the most climate-skeptic overall, even left-wing populists tend to express less support for climate policy and climate science than their non-populist counterparts.

Professor Huber’s closing call for researchers to avoid simplistic conflations and instead carefully disentangle the multiple drivers of populist climate narratives underscored a central lesson for Summer School participants: populism’s engagement with climate change is multifaceted, context-dependent, and inseparable from broader struggles over democracy, legitimacy, and trust in expertise.