In this interview for the ECPS, Dr. Damon Linker delivers a stark assessment of Trumpism’s place in the global surge of right-wing populism. Dr. Linker argues that Donald Trump is “the worst possible example of a right-wing populist,” not only for his ideological extremism but for a uniquely volatile mix of narcissism, vindictiveness, and disregard for constitutional limits. Central to his warning is Trump’s assault on what he calls the democratic “middle layer”—the professional civil servants who “act as a layer of defense” against executive tyranny. By “uniting the bottom and the top to crush that middle layer,” Dr. Linker contends, Trumpism pushes the United States toward an authoritarian model unprecedented in its modern political history.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In this wide-ranging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Damon Linker—Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania, Senior Fellow in the Open Society Project at the Niskanen Center, columnist, and author of The Theocons and The Religious Test—offers one of the clearest and most sobering analyses of Trumpism’s evolving place within the global wave of right-wing populism. Across the conversation, Dr. Linker advances a central contention: Donald Trump is “the worst possible example of a right-wing populist,” not only because of ideological extremism but because of a personally distinctive mix of narcissism, vindictiveness, and strategic opportunism that intensifies the authoritarian tendencies inherent in contemporary populist governance.

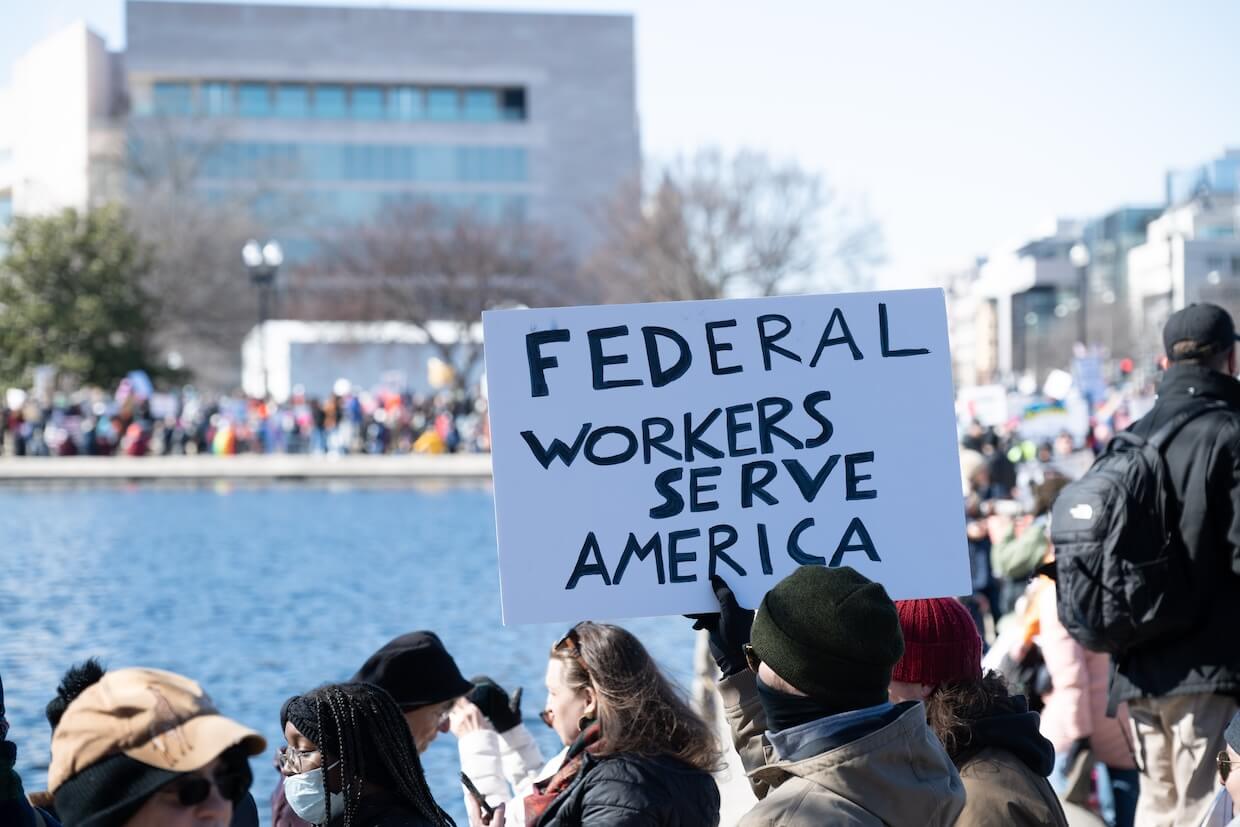

A recurring theme in the interview—and the one that speaks most directly to the headline—is Dr. Linker’s argument that Trumpism seeks to eliminate what he calls the “middle layer” of democratic states. In his formulation, liberal democracies depend on “informed, intelligent, educated… people in that middle layer of the state” who carry out laws, uphold norms, and prevent the executive from “acting like a tyrant.” Trump, by contrast, “tries to unite the bottom and the top in an effort to crush that middle layer—leaving only ‘the people’ and the strongman running the country.” This dynamic, Dr. Linker warns, places the United States closer to the logic of authoritarian rule than at any point in the modern era.

The interview situates Trumpism within both historical cycles and global patterns. Dr. Linker argues that the Republican Party is returning to an older “rejectionist” impulse rooted in its reaction to the New Deal. Yet Trump’s version is more expansive and more radical, because what the right now seeks to overturn is far larger: the post-war regulatory, administrative, and cultural state. At the same time, Dr. Linker stresses that while Trumpism shares features with “authoritarian populism” abroad, Trump himself stands out for being “personally irresponsible… rage-fueled… corrupt… [and] willing to use state power… to hurt his enemies and help his friends.”

The interview also maps the institutional consequences of this project. Dr. Linker shows how Trumpism simultaneously directs bottom-up grievance and top-down coercion to pressure universities, law firms, media, bureaucratic agencies, and cultural institutions. Some actors, he notes, resist, while others “capitulate” under threat of political or financial retaliation. The overall pattern reveals an increasingly fragmented institutional landscape marked by selective vulnerability rather than systemic resilience.

Finally, Dr. Linker reflects on the future of American party politics. If Democrats cannot adapt—by embracing a modestly populist reformism and distancing themselves from the “old, discredited establishment”—they risk long-term marginalization. Yet he remains cautiously optimistic: “As long as we have free and fair elections… my very strong suspicion is [the Democrats] will win again. We just have to be a little patient about it.”

This interview thus offers a penetrating, historically informed account of Trumpism as both a symptom and accelerant of democratic decay in the US—and a warning about what may come next.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Dr. Damon Linker, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

Why Trumpism Isn’t New—But More Dangerous

Dr. Damon Linker, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: You argue that Trumpism expresses a “reactive rejectionism” deeply rooted in the American right’s political DNA. To what extent do you see this as a cyclical return of buried ideological impulses versus a structural transformation of the Republican coalition in the 21st century?

Dr. Damon Linker: Well, I’ve tended to side with the idea that it is something cyclical. The Republican Party responded to the New Deal in the 1930s—Franklin Roosevelt’s vast expansion of the size and scope of the federal government in response to the Great Depression. The party reacted by rejecting that expansion entirely in the name of what we call in the United States, using the French expression, laissez-faire: the notion that the government should not play a significant role in organizing and regulating our political and economic lives, and that if it gets out of the way, the economy will grow and we will see all kinds of positive developments—economically, culturally, and politically. Because the liberal left was working to expand the scope of government, the Republicans developed a program of resistance and rejection.

This remained the party’s dominant position until 1952, when Senator Robert Taft ran for president on that platform. But in the end, the party narrowly chose a different candidate that year—Dwight D. Eisenhower, the former general who helped win the European theater in World War II. He went on to serve eight years as president and adopted a more moderate position, one that enabled the consolidation of the New Deal and continued the Cold War that had been initiated by Democrats and liberals before him.

That moment marked the emergence of a more moderate, mainstream version of the Republican Party, which remained influential on and off until the immediate aftermath of George W. Bush’s presidency. I think Donald Trump represents a return to this older rejectionist form of the Republican Party—although now it rejects much more, because government and the left-liberal agenda have expanded dramatically since the 1930s. So there is much more to contest and attempt to reverse, and I think the impulse to do so helps explain some of the radicalism we’ve seen, especially from this second Trump administration over the past year.

After the Cold War: No Brake on Radicalization

In your framing, the Cold War consensus temporarily disciplined the American right toward moderation. Without an equivalent external threat today, what kinds of internal political or social incentives—if any—could exert a similar moderating force?

Dr. Damon Linker: I’m honestly not sure. My argument is that it’s a bit mysterious what such a force could be. I didn’t go into this in the New York Times essay you’re referring to, but I’m even a little at a loss about whether an external challenge—if it happened today—would have the same effect. Suppose China made an aggressive move against Taiwan and we suddenly became much more concerned about an assertive China in geopolitics. I’m not convinced the Republican Party would respond in a moderating way. At this point, it is so wedded to a kind of Trump-oriented aggressiveness and defensiveness, and to a somewhat conspiratorial and paranoid mindset, that it might meet such a challenge by becoming even more radical about the threat posed by it.

So I’m not sure. I suppose I could say that if Trump ends up being an unsuccessful president—his approval rating is already sinking quite low, and if it drops even lower than it did in his first presidency from 2016 or 2017 to early 2021—and then a Republican successor goes on to lose in 2028, there would be a very lively and rhetorically violent fight among Republicans about where to go next. Out of that struggle, and out of a desperation to win again, it’s possible the party could move even further in an extreme right-wing direction, or it could try to combine some Trump positions—maybe anti-immigration convictions—with a more moderate tone and attitude on other issues.

I’ve long thought that if the Republican Party combined an anti-immigration stance with genuine support for healthcare reform that enabled more people to have access to affordable care, that would be a very potent and powerful combination. But the party has long paired certain cultural right-wing positions with a real hostility to taxes and regulations—a strongly pro-business point of view. And that combination limits its total electoral appeal, so I think they would have to adjust that somewhat.

Populism from Below, Authoritarianism from Above

Many scholars describe democratic backsliding as driven by institutional capture from above and mass polarization from below. How do you interpret the interaction between Trump’s top-down attacks on institutions and the bottom-up radicalization of the Republican base?

Dr. Damon Linker: I affirm the view that combines them both. Trumpism—understood as the American form of right-wing populism we see across much of the world today—brings together exactly these two dynamics. What we have in the United States, as in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and South Asia, where potent right-populist parties and leaders have emerged, is often this same combination: grassroots, everyday voters who are deeply angry with and distrustful of the elite establishment that runs the institutions of public life, and a populist leader who comes along and seeks to champion that discontent and suspicion.

That leader—whether Trump, Erdoğan, Modi, Orban, or others—wins power and then uses the office as a kind of wrecking ball to destroy, radically reform, or undermine the elite system governing the country. We’ve seen this clearly in Trump’s approach during his second term over the past year, as he has sought to channel the desires of everyday voters by dismantling large parts of what we call the administrative state—the career bureaucratic civil servants who run the government across administrations, regardless of whether the president is a Democrat or a Republican.

Trump has tried to fire these people, push them out, or exert total control over them, insisting they conform to his vision of how to run the country “in the name of the people”—the people he claims stand with him against the elites. One way to visualize this is to imagine the base of voters at the bottom, the strongman leader at the top, and the professional civil service in the middle. What Trump tries to do is unite the bottom and the top in an effort to crush that middle layer—leaving only “the people” and the strongman running the country.

And that is very dangerous, because it resembles a dictatorship or authoritarian system far more than a liberal democratic one. In a democracy, you specifically want informed, intelligent, educated people in that middle layer of the state, running things day to day in a responsible way and serving as a buffer—a layer of defense for the rule of law and constitutional norms that prevents the person at the top from behaving like a tyrant. Trump, like many strongmen, is trying to remove that crucial middle layer.

Trumpism Beyond Trump

You describe Trumpism as a long-term phenomenon, not merely a personalistic moment. What, in your view, are the essential ideological and sociological components of Trumpism that will endure after Trump himself exits the stage?

Dr. Damon Linker: The things that I think are likely to fade a little bit are the extreme examples of Trump’s corruption. I do think that corruption is going to increase in the government—probably with both parties but especially among Republicans—simply because Trump has shown that you can be corrupt and get away with it. Now, Trump, as a long-term corrupt figure in our economy and politics—someone who’s a developer and has worked historically in New York City, where the building trades developers are quite corrupt, and he’s been doing it for his entire career of about a half century—I think he’s a kind of outlier, very extremely corrupt, and he’s been very eager in this second administration to do anything he can to enrich himself, his business, his family, and friends.

So, we’ll see some of that, but I think it probably won’t continue at quite the level we’ve seen with Trump. What will continue is the dynamic I’ve already been talking about: seeking to empower the executive branch of our politics by justifying its power in terms of defending “the people.” This kind of populist account of power suggests that it’s acceptable for the leader of the government to act in very extreme ways that seem to transgress the rule of law because it is supposedly done in the name of defending what the people say they want.

In substantive policy terms, the Republican Party will remain very hostile to immigration. It’s also going to be much more skeptical of free trade agreements than it used to be. That doesn’t mean the chaotic imposition of tariffs that Trump has attempted—tariffs he is already backing away from a little because they are hurting our economy so severely. But there is room for a more responsible form of protectionism in our political economy, one that doesn’t offshore supply chains with quite the enthusiasm we’ve seen over the last two or three decades since the 1990s, here and around the world. That trend will continue.

I also think there will be a continued tendency to combine a pro-business economic policy with social conservatism—a long-standing Republican mix since Ronald Reagan. And it will be carried out with more extremism, as Trump has done: very forcefully using the power of the state to combat examples of cultural leftism in the country—in universities, in the corporate sector—while rewarding corporations or businesses that are either explicitly anti-left-wing or simply unpolitical and willing to play ball with, or do business with, the president.

Those businesses will be rewarded with approvals for mergers, a more favorable regulatory environment, and similar benefits, whereas those that continue to push what we call wokeness—a kind of cultural left position—will face a more severe regulatory environment, more meddling, and a generally more difficult time from any Republican president who happens to win the office.

The War on the Administrative State

Your essay in the New York Times highlights the role of the administrative state as a primary target of rejectionist conservatism. Is this assault driven more by ideological hostility to bureaucracy or by a desire to dismantle professional constraints on executive power?

Dr. Damon Linker: I would say both. There is an ideological opposition to the administrative state that has been developed by certain think tanks in the United States,

probably most prominently the Claremont Institute in the suburbs of Los Angeles. Over the last few decades, they have developed a pretty elaborate ideological critique— a critique of and attack on the administrative state—claiming that it is an undemocratic imposition on the Constitution, that the Constitution doesn’t even conceive of. It doesn’t make any provision for it, and so in that respect, it’s wholly illegitimate and should be dismantled.

But at the same time, there is a sense that the administrative state slows down and hinders the will of the president, unless it can be seized by the president and used as a kind of hammer or some other tool to advance his agenda. So what you get on the right these days in this country is this severe critique of how the administrative state has existed and functioned until now, combined with a very confused proposal about what to do about it in the future. Some people say it should simply be gotten rid of—get rid of the administrative state—which, frankly, is very unrealistic. Every modern nation has what we call an administrative state: career civil servants who make the government function and allow it to do what we ask of it, which is regulate our lives, keep us safe, make sure drugs are safe, make sure airplanes don’t fall out of the sky, make sure our cars don’t blow up when they get in a car accident—these kinds of things.

But some on the right are smarter in saying that what we actually need to do is make sure the administrative state doesn’t only help left-wing politicians when they’re in power. Their critique is that when there’s a Democrat as president, the administrative state helps them fulfill their agenda. When there’s a Republican, they do the opposite and drag their feet. They don’t do what the Republican president asks because they don’t agree with it, since

most of the people who work as career civil servants tend to be Democrats. So they come up with excuses not to fulfill the Republican agenda.

So, these people on the right say what we need to do is not get rid of the administrative state; we need to take control of it—fire the left-wing people who work in it and appoint right-wing people who will both advance our agenda when we’re in charge and, secondly, do the opposite to the left when the Democrats return to power. In other words, if the Democrat wants to do a certain thing, these new right-wing civil servants will drag their feet and not implement the proposals. This is a recipe for very wild, big swings from president to president. One advantage of an administrative state—or a career civil service— is that it creates a kind of stability across administrations. Whether you have a Republican president, a Democratic president, a Republican again, a Democrat again, the government as a whole moves a little to one side or the other, but remains anchored in the middle, never veering too far in one direction or the other.

But if all the career civil servants get fired when there’s a new party in charge of the presidency and are replaced with ideologues who agree, you’re going to get something much more volatile, where the whole government shifts 180 degrees in direction. That is a recipe for chaos and a real lack of stability in our system, I fear.

Samuel Francis’s Roadmap to the New Right

Samuel Francis and the “Middle American radicals” have gained renewed attention in analyses of the new right. How central is Francis’s worldview to understanding the intellectual architecture of contemporary Trumpism?

Dr. Damon Linker: The way I usually read prominent intellectuals of the past is a little subtle. You’re talking about a guy named Samuel Francis who died in 2005. He wrote some important essays around 1991–1992 in which he—in retrospect—proposed something that looks a lot like Trumpism. Basically, he articulated a kind of right-populist and right-wing nationalist program, arguing that Republicans needed to begin allying with middle American, middle-class workers against left-leaning bureaucrats and cultural institutions—the elite institutions of American culture. So, as I was saying earlier, you have the bottom and then the populist at the top on the right going to war against the people in the middle—the bureaucrats, the civil servants, and the leaders of universities, the corporate sector, the arts, and cultural institutions. That sounds a lot like a roadmap for Trumpism.

Where I want to hesitate a little bit is that I’m not making the claim that Sam Francis directly caused Trumpism or directly influenced it that much. I think it’s more that he saw a possibility for the right after the Cold War, and he turned out to be correct, although it took a few decades for the Republicans to find a champion in Donald Trump who could actually enact this style of politics and succeed with it politically. Pat Buchanan attempted it with Sam Francis’s influence in 1992, when he challenged George H.W. Bush’s re-election campaign.

He didn’t do that well, although he did get 38% of the vote in the New Hampshire primary that year, which damaged George H.W. Bush. It’s one reason he lost the presidency to Bill Clinton that year. But Pat Buchanan wasn’t able to turn it into that successful of a program to actually win the primaries and take over the Republican Party then. But Donald Trump has succeeded in enacting something like Sam Francis’s ideas, and that is something we need to recognize.

Who Stands Up to Trump—and Who Capitulates?

The Republican Party’s anti-institutionalism now encompasses the judiciary, intelligence services, universities, and media. Which institutional arenas, in your view, remain most resilient—and which are most vulnerable—to coordinated illiberal pressure?

Dr. Damon Linker: I don’t know if I can say that there are any sectors as a whole that can remain resilient. Obviously, the Democratic Party is going to be independent of this and resilient. But beyond that, what you see instead is that within certain segments of the culture, the country, and the economy, certain firms, law firms, and universities are doing better at resisting than others. Some law firms have capitulated to Trump and reached deals with him. Others have said they will not reach deals, and so far it’s not entirely clear—to me at least—

that they’re being punished very severely, so maybe that resistance will continue and even expand.

Similarly with universities: some have capitulated very quickly to Trump in return for having their funding restarted, because Trump cut off a lot of funding for grants in the sciences and medicine. Large, well-endowed universities with prominent medical schools have been particularly vulnerable, like my own University of Pennsylvania, because the Trump administration has been able to shut off grants to these schools, which then gives the president leverage to try to extract concessions from them. But some universities, like Harvard, have tried to fight back, and there are others as well. They will probably continue trying and, hopefully, ride out the rest of the term. There are only three years to go in the second Trump administration. We’ll see. If somehow J.D. Vance becomes president after Trump, or if Trump dies or is incapacitated and Vance takes over during this term and then runs for re-election in 2028 and wins, in those longer-term scenarios it will obviously be harder for these institutions to keep resisting.

But for the moment, again, I wouldn’t say it’s any entire sector. It’s more selective—

people and institutions within many different sectors that are trying to stand up to him, at least a little bit.

Rebuilding the Center-Left for a New Era

You have written extensively on the erosion of the political center. What might a plausible reconstruction of a centrist or “middleground” politics look like in a post-Trump environment, and what forces—if any—could bring it into being?

Dr. Damon Linker: That’s a hard question. I don’t have a great answer for it, because I don’t, frankly, know. My instincts tell me that the road back to power for a kind of center-left coalition has to involve more populism as well. The center-left cannot remain parties of the old, discredited establishment that the right-populist parties have been so successful in targeting. There is obviously a lot of organic irritation and anger with those institutions of the establishment. In order to get a little of that populist energy for themselves, the center-left can’t just say, “Vote for us, and we’ll keep everything the way it’s been for the last

30 to 40 years,” because there aren’t enough people who want to keep things as they’ve been for the last 30 or 40 years. So, if you cede that populist critique and don’t adopt it for yourself, you’re giving ammunition to the populist right to keep winning.

So, the center-left has to acknowledge that this anger against the establishments of our liberal democratic systems is legitimate, that these institutions and the people who run them have made mistakes, they’ve gotten things wrong, and they need to not only acknowledge these errors but come up with proposals to make it better—to fix them, to reform pretty dramatically the way our systems work. Make them more nimble, less bogged down in bureaucracy and red tape, as we put it in one of our favorite metaphors here. And again, try to steal some of that populist energy for the center-left, to, in effect, say: “Yes, I hear you. You’re not happy with the present. Neither are we. We want the government—we want these institutions—to work better for your sake, for all of our sakes.

Trust me, put me into power, and we will make things better. We will make the government run more efficiently and make your lives improve. What we don’t want is those irresponsible people on the other side of the spectrum who really have no positive program at all—they just want to wreck everything. While that might be tempting because you’re angry, the end result is going to be that our lives will get worse, and the government will become even more inefficient, even more incapable of fixing things.”

That’s something like a message that could resonate, but of course you need charismatic, very effective politicians to actually say that in a way that gets people excited. That probably means people who are not the same people who are currently running the show, who clearly are not very compelling to a lot of voters these days.

The Most Extreme Variant of Populism

Trumpism increasingly blends populist grievance with state-driven coercion, such as mass deportation plans and politicized bureaucratic purges. Does this represent a uniquely American synthesis, or does it echo the global pattern of “authoritarian populism” seen elsewhere?

Dr. Damon Linker: In general, it’s continuous with what we’re seeing in other countries. There’s a range. Trump is particularly personally irresponsible and incapable of truly grasping policy details. So, like Meloni in Italy, for example, is a right-wing populist, but her governance has been relatively moderate. If other countries in Europe elected right-populist parties and they governed like Meloni has been governing in Italy, I wouldn’t be that worried about it. I would figure the old neoliberal center-right is now gone—it’s extinct—and instead we have a populist right in countries around the world. I don’t really agree with a lot of those things, but it’s okay; it’s an alternative to the center-left, and that’s now what the alternative ideological configuration is going to look like going forward. We can work with that.

Trump is distinct because he’s so personally narcissistic, so rage-fueled. He hates his enemies. He’s willing to use state power and transgress norms and the rule of law in order to hurt his enemies and help his friends. He’s so corrupt. In all of these ways, he’s sort of the worst possible example of a right-wing populist. So it’s mainly these personal things about him that make him uniquely bad.

So the big question for me is if a J.D. Vance ends up taking over after Trump and winning—how does he govern? How is he different from Trump? Is he more thoughtful, or is he actually worse because he holds the same views but is competent and able to aggressively prosecute their agenda in a way that Trump can’t quite pull off? Because, for example, Trump thinks it makes sense to impose enormous tariffs on every country in the world overnight, as he did last April. I don’t think Vance would ever have done anything that stupid and reckless. If that’s true, then Vance wouldn’t have become as unpopular as Trump has become. So that’s one question that I wonder and worry about.

A Stress Test for the American Party System

And lastly, Dr. Linker, if Trumpism remains ascendant even after scandals, governance failures, and electoral defeats, what does this suggest about the adaptive capacity—or decay—of the American party system?

Dr. Damon Linker: It means that the Democratic Party is in trouble. Now, it’s not in trouble in the way the Republican Party was in the 1930s, when Franklin Roosevelt won re-election in 1936 with 60.8% of the vote, and Democrats controlled the US Senate with 75 seats out of 96, and the House of Representatives—if I recall correctly—334 to 88. Absolutely lopsided margins in favor of the Democrats, where the Republicans almost looked like they were going out of business.

The Democrats today can still come close to winning. It’s very, very narrow in Congress right now—only 3 or 4 seats separate the two parties—so that means the Democrats can almost win, and they could win again. They could win in the midterm elections next year; they could win the presidency in 2028. If they lose in these elections again, that would mean that they’re in trouble. But they probably are not going to lose in a landslide that signals they have to fundamentally change. It would mean they have to adjust their message in ways like I’ve been advocating in some of the earlier things I said.

So, as long as we have free and fair elections—even if the populist-right Republican Party is winning these elections—we still have the possibility of the Democrats winning at some point in the future, and my very strong suspicion is they will win again. We just have to be a little patient about it.