Please cite as:

Marcos-Marne, Hugo. (2024). “Euroscepticism and Populism on Europhilic Soil: The 2024 European Parliament Elections in Spain.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0084

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON SPAIN

Abstract

This chapter deals with the association between radicalism, populism and Euroscepticism in the context of the 2024 European elections. It first examines the electoral platforms of leading political parties and shows that Eurosceptic ideas, while not highly prevalent, are more common among forces of the radical right. It also suggests that, as second-order theories expect, national issues dominated the electoral campaign for the European Parliament (EP) in Spain. Second, public opinion data is used to describe the general state of attitudes towards the EU and their association with voting for different political parties. The main results from this section are evidence that voters of radical-right parties are more critical of the EU. They also underline a potential reconfiguration of the radical-right space that now includes Vox and a new anti-establishment, outsider formation, The Party is Over (Se Acabó La Fiesta, SALF).

Keywords: Euroscepticism; populism; radical-right; ideology; Spain

By Hugo Marcos-Marne* (Department of Political Science and Public Administration, University of Salamanca, Spain)

Introduction

The 2024 European Parliament (EP) elections in Spain took place against a backdrop of political polarization and instability. The general elections in July 2023 resulted in a fragmented parliament, requiring the candidate from the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE), Pedro Sánchez, to secure the support of eight different parties and coalitions to be re-elected prime minister. The coalition supporting Sánchez, which included peripheral nationalist parties heavily criticized by right-wing forces, only intensified the existing trends of polarization (Parker, 2022). Political discussions often included accusations of lawfare, insults, and questioning of the government’s legitimacy to a scale not seen before (Jones, 2024). It is no surprise that more than 75% of the population defined the political situation as ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’, according to data gathered in June 2024 by the Spanish Centre of Sociological Research (CIS) (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 2024c).

The number and relevance of ongoing national-level political issues often sidelined European ones during the 2024 campaign. Topics recurrently discussed included the amnesty law applied to events referring to the independentist movement in Catalonia between 2012 and 2023, alleged corruption scandals around Sánchez and the PSOE, and international issues not directly related to the European Union (EU), such as Spain’s recognition of the Palestinian State and a diplomatic incident with the Argentinian president Javier Milei. Analysts widely agreed that the electoral campaign was framed as a referendum against Sánchez by the right-wing Partido Popular (PP) and far-right Vox (Kennedy & Cutts, 2024). Still, European issues appeared during the campaign, and special attention was given to the potential success of the radical right and its influence on EP alliances. Relevant in this regard was the emergence of a new anti-establishment, outsider formation in Spain, The Party is Over (Se Acabó La Fiesta, SALF), led by the former political adviser and alt-right influencer Luís Pérez (known as Alvise Pérez). The Spanish party system, once depicted as immune to the radical right (Alonso & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2015), included two genuinely radical-right contenders for the EP elections in 2024.

Building upon this background, this chapter focuses on the association between Euroscepticism, radicalism and populism before and during the European elections campaign in Spain. For that, it uses secondary sources and public opinion data from the CIS (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 2024b; 2024c). The main results suggest that Euroscepticism was comparatively low in Spain both on the demand and supply side, although it was stronger among radical-right parties and their supporters (see Llamazares & Gramacho, 2007). They also evidence a potential re-composition of the radical-right space with the competition between Vox and SALF, the latter with a more heterogenous voter profile regarding self-positioning on the left–right scale and an even stronger impugning discourse towards mainstream politics.

Euroscepticism and populism in Spain

Spain is depicted as a Europhilic country. Citizens and parties had always had positive perceptions of the EU until 2008 (Powell, 2003; Real-Dato & Sojka, 2020; Vázquez García et al., 2010), and widespread critical positions among the public disappeared with the more negative consequences of the crisis (Gubbala, 2023). In April 2024, the CIS gathered data on attitudes towards the EU (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 2024a). This report showed that Spaniards acknowledged the importance of the EU (more than 82% of the respondents thought that EU decisions matter a lot or quite a lot for the life of the Spaniards) and considered that EU membership had been more positive than not for salaries, employment opportunities, culture, development of less developed regions, business opportunities, and the relevance of Spain in world affairs (this was not the case only for one item, the price of consumption goods). In fact, large majorities supported strengthening EU common foreign policy, creating a European army, having a common policy of migration and asylum, harmonizing taxes, having a common policy of rights and obligations, and economically contributing to creating a European welfare state (Table 1).

Table 1. Percentage of respondents in favour or against key EU policies and actions

| In favour% | Against% | |

| Strengthen European common foreign policy | 83.3 | 13.4 |

| Creating a European army | 63.5 | 32.7 |

| Having a European common policy of migration and asylum | 78.1 | 19.2 |

| Harmonizing taxes | 62.9 | 29 |

| Having a common policy of rights and obligations | 87.1 | 9.9 |

| Economically contribute to creating a European welfare state | 80.7 | 16.5 |

Source: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (2024a)

Nevertheless, post-2008 outcomes included a comparatively more Eurocritical party system with the emergence of Podemos and especially Vox. While Podemos mostly targeted neoliberal policies at the EU level, Vox included more explicit references against the EU as a supranational organization, which could have attracted voters who oppose the European integration process (Marcos-Marne, 2023). Data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) confirm that both PSOE and PP had a favourable/strongly favourable position towards EU integration, Podemos had an opinion between neutral and somewhat positive, and Vox had a somewhat opposed one. The most critical party in Spain, Vox, still ranks higher in EU support than other parties of the radical-right family, such as the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV), the French Rassemblement National (RN), or the German Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) (Hooghe et al., 2024). The position of the recently created SALF remains unclear because the candidature did not present a structured manifesto for the EP elections. Still, the strongly nationalist and anti-establishment discourse of its leader anticipates a critical discourse towards the EU that might take different forms and intensities.

Considering that both Euroscepticism and populism are often found at the extremes of the ideological spectrum (Hooghe et al., 2002; Rooduijn & Akkerman, 2015), it is no surprise that Podemos and Vox have been more frequently studied regarding populism. According to the ideational approach, populism is found in the intersection between anti-elitism, people-centrism, and a Manichean understanding of politics (Hawkins et al., 2019; Wuttke et al., 2020). Following this definition, Podemos has been said to display a more populist discourse than Vox (Marcos-Marne et al., 2020, 2024), but recent analyses signal a decline in the use of populist ideas by Podemos, which has turned more clearly to radical-left ones (Roch, 2024; Rojas-Andrés et al., 2023). As for Movimiento Sumar (‘Unite Movement’), evidence suggests it does not include populist ideas in its discourse (Thomassen, 2022). Regarding SALF, there is little doubt that anti-elitism, especially against parties of the left, is a fundamental part of its electoral platform, but the use of people-centred ideas is much less clear. At the moment of writing, SALF may be characterized as a far-right protest movement that expresses a demagogic/impugning discourse. It must be acknowledged, however, that there is space for SALF to incorporate populist ideas in a more consistent manner.

Overall, the electoral competition in 2024 Spain seemed better explained by where parties sit in the economic, cultural and centre-periphery axes of competition. This does not mean that populist ideas were irrelevant during the electoral campaign, and it certainly does not preclude populism from again becoming a key component of the political competition in the future. However, it helps to understand that most of the electoral claims, including positioning towards the EU, correlated strongly with left–right positioning in the economic and cultural dimensions. For example, in the Spanish public television debate for the EP elections, Jorge Buxadé (Vox) was the politician who most clearly framed his intervention as an opposition between the interest of Brussels and the Spanish people. Candidates from Podemos and Sumar directed criticisms towards the EU due to its (non)response to the Israel attacks in Palestine but also emphasized the importance of a green and fair Europe that considers the welfare of its peoples. This clearly evidences the relevance of the thick ideology to which populist ideas attach when it comes to EU contestation (Massetti, 2021; Roch, 2020).

The EP 2024 elections: Results, trajectories and electorates

The results of the EP elections in Spain (Table 2) resembled general trends at the European level. A movement towards the right was observed, with the PP being the most-voted force (34% of the valid votes) and parties defending radical-right platforms increasing their vote share (Vox and SALF received together almost 15% of the valid votes). Nevertheless, mainstream forces of the left and right retained most of the MEPs (PP and PSOE secured more than 64.2% of the valid votes and 42 out of Spain’s 62 MEPs). In line with aggregate results, parties integrated into The Left group experienced a decline in electoral support, which can also be attributed to a series of public disputes between Sumar and Podemos.

To put these results into perspective, Vox clearly improved its results from the 2019 EP elections (6.21%), but it lost significant support when compared with the 2023 general elections (12.4%). The emergence and success of SALF are likely to have contributed to this, as according to CIS data, more than 50% of its electorate had supported Vox in the past general elections. Podemos, which together with Izquierda Unida (IU) received 20% of the vote in 2016, only gained two seats in the EP (3.3% of the valid vote). The declining electoral trajectory of Podemos can only be explained by referring to multicausal explanations from punishment to internal divisions, organizational disputes, engagement with institutional power, and the recovery of both macroeconomic indicators and mainstream parties (crucially, PSOE).

Table 2. EP electoral results in Spain

| Party or coalition | European family | Vote share (%) | Seats in the EP |

| Partido Popular (PP) | European People’s Party (EPP) | 34.2 | 22 |

| Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) | Socialists and Democrats (S&D) | 30.2 | 20 |

| Vox | European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) | 9.6 | 6 |

| Ahora Repúblicas | Greens–European Free Alliance (EFA) / The Left | 4.9 | 3 |

| Sumar | Greens–European Free Alliance (EFA) / The Left | 4.6 | 3 |

| Se Acabó La Fiesta (SALF) | Other | 4.6 | 3 |

| Podemos | The Left | 3.3 | 2 |

| Junts-UE | Non-attached (NA) | 2.5 | 1 |

| Coalición por una Europa Solidaria (CEUS) | Renew Europe | 1.6 | 1 |

Source: https://results.elections.europa.eu/es/

To explore the central ideological, attitudinal and sociodemographic differences between voters of different parties, I pay attention to voters of the two mainstream parties of the left and right (PSOE and PP) and the four statewide parties that can be clearly associated with the radical left (Podemos and Sumar) and right (Vox and SALF). This section has used CIS data, particularly the 2024 May barometer (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 2024b) (N= 4,013) and the pre-electoral study conducted for the EP elections (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 2024c) (N=6,434). The study conducted in May 2024 incorporates different questions that are important to understand the profile of voters, but it did not include voters of SALF.

Relevant differences can be seen in the positions of voters on key issues that affect the EU, such as climate change or the war in Ukraine and Palestina (Table 3). Podemos and Sumar voters were by far the most concerned about climate change, followed by PSOE voters. The percentage of voters of PP and Vox that were very concerned about climate change did not reach 20%, and it was the lowest for Vox, reflecting general associations between attitudes towards climate change and left–right ideology (McCright et al., 2016). Vox and Podemos voters were the least concerned about the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These voters perceive the negative consequences of the war to a similar extent as the average population, but they seem less concerned for different reasons. On the one hand, Podemos voters declared higher levels of sympathy towards Russians. On the other hand, Vox voters declared comparatively lower levels of sympathy towards both Russians and Ukrainians.

Accordingly, it could be that more pronounced preferences for one side and indifference towards both contribute to explaining lower levels of concern about the conflict. In any case, this does not speak of a general perception towards international conflict. Podemos voters were also the most concerned about war in the Middle East region. Overall, voters of left-wing forces were clearly more concerned about war in Palestine than Ukraine. This was particularly visible among Podemos voters and can be explained by the association between left-wing ideologies/parties and the Palestinian people in Spain (Musuruana & Hermosa Aguilar, 2022).

Table 3. Percentage of different parties’ voters very concerned about…

| PSOE | PP | Vox | Sumar | Podemos | |

| Climate change | 40.9% | 19.9% | 13.2% | 59.7% | 61.3% |

| Russian invasion of Ukraine | 32% | 26.2% | 15.5% | 26.6% | 13.5% |

| War in the Middle East | 41.6% | 25.6% | 17.9% | 52.3% | 53.3% |

Source: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (2024b).

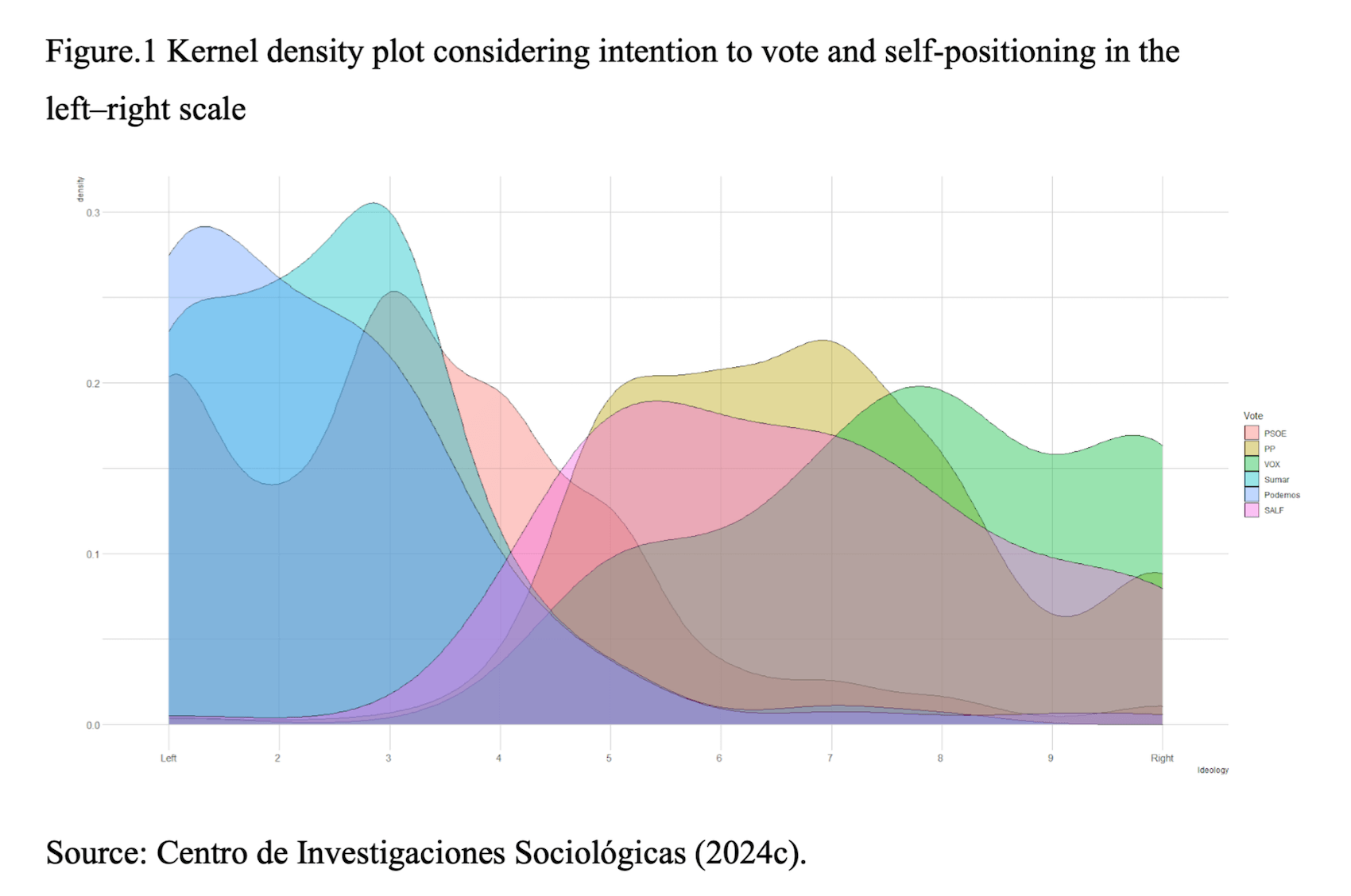

Moving to data from the pre-electoral study, Figure 1 shows relevant information regarding voters’ positioning on the left–right scale. Unsurprisingly, voters of Podemos and Sumar were more clearly positioned to the extreme left of the scale. Voters of PSOE were more often situated to the centre-left of the scale, and PP voters were more to the right. Despite the transfer of votes and some attitudinal similarities between Vox and SALF voters, their ideological profiles seemed quite different. Vox voters self-identified with right and especially radical-right positions, but voters of SALF were more numerous at the centre-right of the ideological scale. This raises important questions about the extent to which the voters widely share the radical-right platform of Pérez or whether his electoral success is partially explained by the dynamics of protest voting that is more easily expressed in the European elections (Hix & Marsh, 2007).

Tables 4–6 below show the aggregated sociodemographic and attitudinal characteristics of the supporters of the most-voted parties. Vox and especially SALF had clearly masculinized electorates (only 21% of SALF voters were women), but the profile of their voters differed regarding catholic identification (more Catholics support Vox), level of studies (SALF gathered more support among people with higher education), economic features (SALF was comparatively more popular among employed people and performed the worst among those with the lowest income), and mean age (SALF voters were the youngest in the sample). Voters of SALF were those who more clearly defined themselves as ‘mostly Spanish’ and showed the lowest levels of identification with Europe. Similarly, voters of Vox also thought of themselves mostly as Spanish but showed a comparatively higher level of dual Spanish–European identity. The more cosmopolitan voters were those of Podemos and Sumar (Table 5). Results in Table 6 suggest that voters of Vox and SALF were also the most critical regarding the benefits of EU membership (PSOE voters were the most satisfied).

Table 4. Sociodemographic features in voters for main parties in the EP elections

| PSOE | PP | Vox | Sumar | SALF | Podemos | |

| Female | 55.9% | 53.1% | 39.4% | 48.1% | 21.3% | 52.2% |

| Catholic | 62.1% | 80.1% | 72.7% | 12.2% | 52.9% | 14.2% |

| Higher studies | 30% | 35.1% | 21.4% | 49.8% | 40.2% | 39.3% |

| Less than €1,100 | 13.4% | 12.5% | 18.2% | 9.8% | 9.2% | 10.6% |

| Employed | 44.2% | 53.2% | 59.4% | 66.8% | 79.6% | 57% |

| Mean age | 55.8 | 55 | 42.9 | 47.5 | 36.9 | 49.2 |

Source: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (2024c).

Table 5. European identity among voters for main parties in the EP elections

| PSOE | PP | Vox | Sumar | SALF | Podemos | |

| Mostly European | 4.7% | 2.5% | 1.5% | 7.4% | 0.5% | 7.3% |

| Mostly Spanish | 18.2% | 31.7% | 56.6% | 8.6% | 64.9% | 11.8% |

| Both European and Spanish | 54.7% | 55.9% | 31.6% | 39.6% | 20.5% | 21.2% |

| Citizen of the world | 21.8% | 9.6% | 9.1% | 43.5% | 13.7% | 54.7% |

Source: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (2024c).

Table 6. Spain mostly benefited from or affected by EU membership

| PSOE | PP | Vox | Sumar | SALF | Podemos | |

| Mostly benefited | 87.8% | 79.2% | 43.5% | 82.5% | 33.3% | 78.3% |

| Mostly affected | 8.8% | 15.9% | 50.8% | 12.5% | 58% | 18.4% |

Source: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (2024c).

Conclusion and implications

The results of the 2024 EP elections in Spain resembled larger trajectories unfolding at the EU level. Mainstream parties of the centre-left and right were still the most supported forces, but radical-right forces grew both in number and votes. These forces are characterized by more Eurosceptic discourses that also resonate more strongly with their voters. While populist ideas are sometimes present in their discourses, it is essentially the anti-elitist component of populism that they use more often, sometimes combined with demagogy (especially visible in SALF). While there is no evidence to support a short-term electoral earthquake in Spain that would push forward radical-right forces, mainstream parties should reflect on the extent to which normalizing and incorporating discourses of the radical right complicates both their electoral performance and the project of the EU.

(*) Hugo Marcos-Marne is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Salamanca and a member of the Democracy Research Unit (DRU) at the same institution. Before joining USAL, he occupied postdoctoral positions at SUPSI-Lugano (Switzerland), the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland), and UNED (Spain). His research focuses on public opinion, electoral behaviour, populism and national identities. His work has been published in Political Behavior, Political Communication, Political Studies, Politics and West European Politics, among other journals. He is also a co-author of a book recently published by Cambridge University Press.

References

Alonso, S., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2015). Spain: No Country for the Populist Radical Right? South European Society and Politics, 20(1), 21–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2014.985448

Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (2024a). Estudio 3452: Opiniones y actitudes ante la Unión Europea [Study 3452: Opinions and attitudes towards the European Union]. CIS, April 2024. https://www.cis.es/es/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&codEstudio=3452

Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (2024b). Estudio 3457: Barómetro de Mayo [Study 3457: May Barometer]. CIS, May 2024. https://www.cis.es/es/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&codEstudio=3457

Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (2024c). Estudio 3458: Preelectoral elecciones al Parlamento Europeo 2024[Study 3458: Preelectoral European Parliament Elections]. CIS, May 2024. https://www.cis.es/es/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&codEstudio=3458

Gubbala, S. (2023). People broadly view the EU favorably, both in member states and elsewhere. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/10/24/people-broadly-view-the-eu-favorably-both-in-member-states-and-elsewhere/

Hawkins, K., Carlin, R., Littvay, L., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2019). The Ideational Approach to Populism. Concept, Theory, and Analysis. Routledge.

Hix, S., & Marsh, M. (2007). Punishment or Protest? Understanding European Parliament Elections. The Journal of Politics, 69(2), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00546.x

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Bakker, R., Jolly, S., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2024). The Russian threat and the consolidation of the West: How populism and EU-skepticism shape party support for Ukraine. European Union Politics, 14651165241237136. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165241237136

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Wilson, C. J. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies, 35(8), 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310

Jones, S. (2024). Spain’s PM Sánchez could quit after far-right attacks on wife and bid to ‘politically kill’ him. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/apr/28/spains-pm-sanchez-could-quit-after-far-right-attacks-on-wife-and-bid-to-politically-kill-him

Kennedy, P., & Cutts, D. (2024). Spain: the 2024 European Parliament elections – more turbulence ahead? LSE blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2024/05/14/spain-the-2024-european-parliament-elections-more-turbulence-ahead/

Llamazares, I., & Gramacho, W. (2007). Eurosceptics among Euroenthusiasts: An analysis of Southern European public opinions. Acta Politica, 42(2–3), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500180

Marcos-Marne, H. (2023). A Broken National Consensus? EU Issue Voting and the Radical Right in Spain BT–The Impact of EU Politicisation on Voting Behaviour in Europe (M. Costa Lobo (ed.); pp. 299–322). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29187-6_12

Marcos-Marne, H., Plaza-Colodro, C., & Hawkins, K. A. (2020). Is populism the third dimension? The quest for political alliances in post-crisis Spain. Electoral Studies, 63, 102112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.102112

Marcos-Marne, H., Plaza-Colodro, C., & O’Flynn, C. (2024). Populism and new radical-right parties: The case of VOX. Politics, 44(3), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957211019587

McCright, A. M., Dunlap, R. E., & Marquart-Pyatt, S. T. (2016). Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Environmental Politics, 25(2), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2015.1090371

Musuruana, C., & Hermosa Aguilar, L. (2022). Apoyo y preocupación hacia el pueblo palestino en Argentina y España. Efectos del nivel de conocimiento sobre el conflicto palestino-israelí. Revista Española de Sociología, 31(2 SE-Artículos), a103. https://doi.org/10.22325/fes/res.2022.103

Parker, J. (2022). Why Spanish Politics is Becoming More Polarised. https://politicalquarterly.org.uk/blog/why-spanish-politics-is-becoming-more-polarised/

Powell, C. (2003). Spanish Membership of the European Union Revisited. South European Society and Politics, 8, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608740808539647

Real-Dato, J., & Sojka, A. (2020). The Rise of (Faulty) Euroscepticism? The Impact of a Decade of Crises in Spain. South European Society and Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2020.1771876

Roch, J. (2024). De-centring Populism: An Empirical Analysis of the Contingent Nature of Populist Discourses. Political Studies, 72(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217221090108

Rodon, T., & Rodríguez, I. (2023). A bitter victory and a sweet defeat: the July 2023 Spanish general election. South European Society and Politics, 28(3), 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2024.2326300

Rojas-Andrés, R., Mazzolini, S., & Custodi, J. (2023). Does left populism short-circuit itself? Podemos in the labyrinths of cultural elitism and radical leftism. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2023.2269375

Rooduijn, M., & Akkerman, T. (2015). Flank attacks: Populism and left–right radicalism in Western Europe. Party Politics, 23(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815596514

Thomassen, L. (2022). After Podemos: Yolanda Díaz’s Post-Populist Project For Spain. https://www.psa.ac.uk/psa/news/after-podemos-yolanda-díaz’s-post-populist-project-spain

Vázquez García, R., Delgado Fernández, S., & Jerez Mir, M. (2010). Spanish political parties and the European Union: Analysis of Euromanifestos (1987–2004). Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11(2), 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705851003764380

Wuttke, A., Schimpf, C., & Schoen, H. (2020). When the Whole Is Greater than the Sum of Its Parts: On the Conceptualization and Measurement of Populist Attitudes and Other Multidimensional Constructs. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 356–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000807