In a thought-provoking interview with the ECPS, Professor Stephen E. Hanson unpacks how US President Donald Trump exemplifies a growing global trend of patrimonial rule. Professor Hanson argues that Trump governs as if the state was his personal property—distributing power to loyalists, undermining impartial governance, and attacking state institutions. Drawing comparisons to Russia, Hungary, and Brazil, he warns of long-term damage to democratic institutions. Professor Hanson stresses the need for renewed public trust in government and a collective effort to counteract the erosion of modern governance.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In an in-depth interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Stephen E. Hanson, the Lettie Pate Evans Professor in the Department of Government at William & Mary University, offers a compelling analysis of the erosion of modern governance under US President Donald Trump. Drawing on his co-authored works The Global Patrimonial Wave and The Assault on the State, Professor Hanson argues that Trump’s presidency exemplifies a broader 21st-century resurgence of patrimonial rule—a system in which leaders govern as if the state were their personal property.

Professor Hanson underscores that “the key features [of Trump’s governance] are that the ruler governs the entire state as if it were his personal possession, viewing the state as a kind of family business. He distributes parts of the state and its protection to loyalists, cronies, and even family members directly. At the same time, he attacks the impersonal and impartial administration of the state as an obstacle to his arbitrary power.” This, he argues, is a defining characteristic of patrimonialism, a governance style that many assumed had been relegated to history but is now re-emerging in modern democracies.

Through the course of the interview, Professor Hanson details how Trump’s administration actively worked to dismantle bureaucratic institutions, a trend he links to similar developments in Russia, Hungary, Turkey and Brazil. He explains that Trump’s refusal to accept the 2020 election results—mirroring tactics used by patrimonial rulers—posed unprecedented risks to American democracy, undermining public trust in institutions like the electoral system and the judiciary.

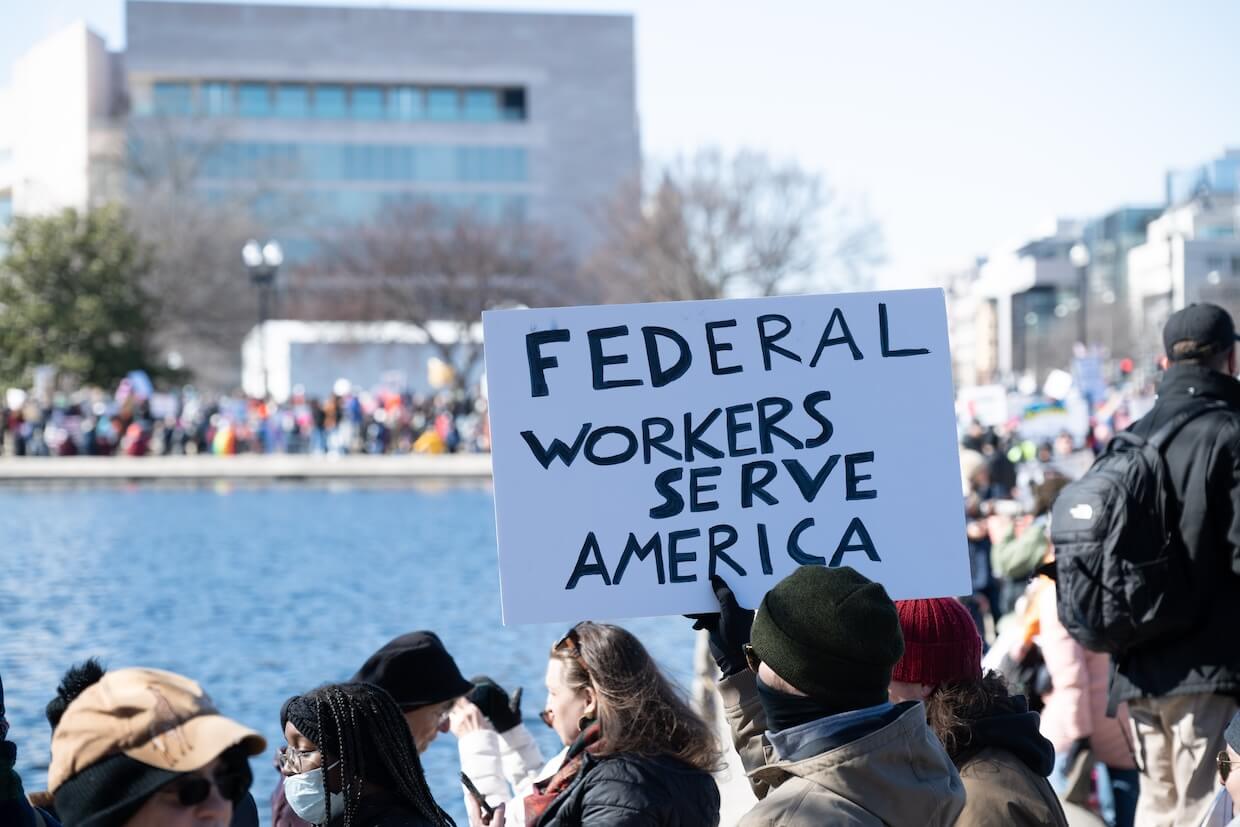

Professor Hanson also addresses the long-term consequences of Trump’s governance, particularly in how it has fueled distrust in expertise and weakened state capacity. He describes how, under Trump, public service was increasingly devalued, discouraging young professionals from pursuing government careers. “At this moment, no one in their right mind would join the federal government—massive layoffs are happening, and every office is being downsized,” he warns, emphasizing that rebuilding state institutions will be a daunting, long-term challenge.

Yet, Professor Hanson remains hopeful, advocating for a reassertion of the state as a force for public good. He stresses the need for new strategies to counteract patrimonialism, urging scholars, policymakers, and civil society to shift the discourse toward defending democratic governance. His insights offer a sobering but essential perspective on the ongoing assault on the modern state—and what can be done to reverse it.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Stephen E. Hanson with some edits.

How Trump’s Governance Undermined the Modern State

Professor Hanson, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: In “Understanding the Global Patrimonial Wave,” you discuss the resurgence of patrimonial rule. How does Trump’s presidency fit into this framework, and what long-term effects might his style of governance have on American democracy?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: Thanks for this question. I want to begin by acknowledging my co-author, Jeffrey Kopstein, who, of course, can’t join us for this interview, but everything we’ve done together is a completely equal collaboration. So I always begin by acknowledging his great work.

We do think, sadly, that our predictions in The Global Patrimonial Wave and The Assault on the State, the book we’ve just published, have unfortunately come true. The Trump administration, in its early weeks, has fulfilled these predictions practically, and we believe that our warning was, unfortunately, quite prescient.

Now, what did we see coming down the road? We argued that this new version of patrimonial rule is really a wave of the entire 21st century and quite unexpected. The old literature on patrimonialism—or neopatrimonialism, as it was often called—assumed it was a relic of traditional society destined to be overthrown by modernity. You might see periods of patrimonial interludes, particularly in the developing world, but nobody had predicted patrimonialism of the 19th-century sort, or even earlier, in countries like the US, Israel, the UK, much of Central and Eastern Europe, and now threatening the world.

So, we’ll discuss more details about the Trump administration in this interview, but the key features are that the ruler governs the entire state as if it were his personal possession, viewing the state as a kind of family business. He distributes parts of the state and its protection to loyalists, cronies, and even family members directly. At the same time, he attacks the impersonal and impartial administration of the state as an obstacle to his arbitrary power.

All of this comes directly from Max Weber, and in a way, we are simply applying Weber’s analysis to these unexpected 21st-century cases.

You highlight how strong bureaucratic institutions played a key role in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. How did the Trump administration’s approach to governance impact the US response to the crisis, and do you see lasting damage to state capacity?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: We discuss this extensively in both the book and the article. What we argue is that patrimonial-style politics is fundamentally ill-suited for handling global pandemics. The first casualty of patrimonialism is the public good because governance is not about serving the public—it’s about fulfilling the private will of the ruler.

As a result, we see poor performances in countries governed by patrimonial rulers. If we compare data statistically, countries like Russia under Putin and the US under Trump performed very poorly. Patrimonial states tend to foster both distrust in the government—which discourages people from getting vaccinated or trusting experts—and the arbitrariness of the ruler himself. Trump’s public appearances, for example, where he seemingly endorsed sunlight as a cure for COVID-19 or suggested injecting bleach in front of his expert advisors, contributed to the excess death toll in the US compared to countries like Canada, which handled the crisis much more effectively.

Now, there are instances where patrimonial-style rulers managed certain aspects of the pandemic well. For example, Operation Warp Speed under Trump led to the rapid development of the vaccine, and Netanyahu’s vaccination campaigns in Israel were quite effective. However, we argue that these successes were not the result of patrimonial rule itself but rather the legacy of state-building efforts that predated these leaders. They were able to deploy existing state capacity, experts, and institutions in response to the crisis. But, of course, if the state is eroded too much over time, those resources will no longer be available in the future.

Rethinking Regimes: Why the Democracy-Autocracy Divide Is Not Adequate

Your work discusses the global trend of leaders undermining bureaucratic institutions. How does Trump’s presidency exemplify this, and what challenges does this pose for future administrations attempting to restore trust in expertise?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: The book is called The Assault on the State, and I think one reason it’s now getting some attention is that the title encapsulates what we expected to happen under Trump. Maybe even we were surprised by the extent of the assault on the state. It’s not just an attack on the so-called "deep state" as a rhetorical device—it’s an actual effort to dismantle the entirety of the US federal government. With DOGE, the agency essentially created out of the blue and directed by Elon Musk in all but name, they are now going into every single state agency in the United States. They have very young people, between the ages of 18 and 25, embedded in agencies, looking at files, personnel issues, and money flows.

While there has been some effort lately to cut that back—largely due to the anger of Trump’s Cabinet ministers—it is still in place. The long-term damage to state capacity is incalculable.

So all of this fits within our framework, but in an extreme form. I’ll add one thing that might actually be a bit surprising—and perhaps even, in a strange way, good for those of us who want to restore the state. This is happening so quickly that the damaging effects will become apparent sooner rather than later. If that happens, maybe public opposition can also be mobilized more quickly.

You argue that traditional democracy/autocracy classifications are insufficient. Given Trump’s attempts to subvert democratic norms, where would you place his presidency within your broader conceptual framework?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: One of the arguments in the book that has actually been a little bit controversial—and difficult to convey to people—is that we really don’t think the democracy-autocracy divide is adequate to understand this phenomenon. It’s ingrained in how we think about political regimes; it’s the standard framework used by political scientists, social scientists, and journalists alike.

When we talk about regime types in political science, people assume it’s a scale measured by V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy), Polity, or Freedom House. In each case, there’s a line ranging from positive—representing the most democratic—to negative—representing the most autocratic.

One reason we failed to recognize the rise of patrimonialism earlier is that it doesn’t fit into this framework. A patrimonial-style ruler can win free and fair elections repeatedly. In some cases, they even thrive in electoral competition. Trump is a great example of this, as is Boris Johnson. These leaders leverage populist tropes, portray machismo, and rail against the so-called "deep state" bureaucracy or, in the case of Europe, anti-EU politicians in Brussels. This rhetoric has a strong popular appeal, allowing them to win elections handily.

When they do, it becomes difficult to argue that they are anti-democratic, given that they just won an election. So, we argue that the axis needs to change. Our analysis must shift to a second dimension: impersonal versus personalized state governance. This concept is rooted in Weberian sociology.

If this is an independent axis, it implies that there are four regime types, not just two. You can have bureaucratically rational democracies—Denmark or Canada come to mind. You can also have personalized democracies, which are patrimonial—this is the US under Trump. Similarly, you can have personalized autocracies, which are quite common, and bureaucratic autocracies, like Singapore or the 19th-century Prussian Rechtsstaat model.

If this two-by-two framework holds, then we need to recognize that patrimonialism can exist within democratic systems without immediately eroding their democratic nature. In cases like the Philippines, voters essentially choose which patrimonial clan will rule—whether it’s Duterte’s or the Marcos family’s—but the patrimonial style remains constant. These hybrid forms of governance challenge our traditional political science classifications, requiring us to rethink how we analyze regime types.

The Legacy of Trump’s Election Denial

Trump’s refusal to accept the 2020 election results mirrors tactics used by patrimonial rulers. How does this compare to other historical or global cases, and what risks does it pose for future US elections?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: Well, connecting to what we just talked about, the January 6th events and Trump’s unwillingness to admit defeat are somewhat unusual in these cases. The reason for that is that, typically, you either have a clear-cut electoral victory—like Orbán in Hungary, where he wins elections that propel him to absolute power, securing a parliamentary supermajority that allows him to amend the constitution over time—or you have leaders who reluctantly step aside without outright denying their defeat. In Orbán’s case, the space for democratic competition clearly erodes, but it happens through legal mechanisms. He doesn’t need to claim the election was fake because, in fact, he won.

There may be some elements of this with Boris Johnson’s departure, where he was reluctant to step down and continued to complain that his downfall was somehow orchestrated by others. However, he never actually claimed he deserved to be the permanent ruler, and, of course, he exited through parliamentary means rather than an election dispute.

In this respect, Trump’s insistence that he never lost the election, that it was all rigged, and that the so-called "deep state" blocked his victory is somewhat unusual in the annals of these regime types. However, it has played a significant role in further undermining trust in US state institutions—particularly in voting systems, ballot counting, and electronic voting machines.

This poses a serious issue going forward. While, as I mentioned earlier, you can have a patrimonial democracy that remains competitive, it does erode the quality of democracy over time. If the public becomes convinced that the ballot box is rigged and that votes are fake, then eventually, supporters can be persuaded that their candidate won even when they actually lost. This, of course, can lead to even worse regime outcomes.

Western Democracy in Crisis

Your research connects US political shifts to broader global patterns. Does Trump’s rise signal a deeper systemic failure in Western democracies, and how can the US counteract these trends moving forward?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: It’s definitely a bad situation. And we should add—Jeff and I are definitely in favor of democracy. Sometimes we get asked this question: "You’re so concerned about the State. Would you rather have a Reichstadt with no democracy than a democracy that’s patrimonial in some ways?" And the answer to that question is that we don’t have to make that choice.

The reality right now is that there’s no Reichstadt or a Singapore-style uncorrupted autocracy on offer. The only options available are populism in a democratic context and patrimonialism in the state context versus the old forms of liberal, rational-legal order, to use Weber’s terminology.

So part of our goal is to reclaim the State as a positive entity. We’ve seen it is bashed for so long from both the left and the right. Libertarians argue that the State is a block to liberty. On the left, critics see the military-industrial complex and the surveillance state as suppressing the people‘s will. Religious nationalists believe the State is too secular and is stamping out religious life—and this isn’t just in the US but also in places like Russia. It’s different religious traditionalisms, but with the same kind of complaint.

The idea that the secular modern state is a good thing, that it helps protect the public welfare, is often missing from our political discourse. When you defend the State, you sound like you’re upholding an old, discredited status quo. But we should recognize that it’s not actually the status quo—that’s the whole problem.

This also connects to another issue. We are definitely in the camp that says neoliberalism has a lot to answer for over the last 30 years. The notion that the State should be reconstructed solely in service of markets, that it should be downsized as much as possible to become more efficient, or that the old welfare state was bloated and ineffective—those arguments, we believe, did significant damage. The financial crises of 2008 and then 2010–11 convinced many that the so-called meritocrats were not meritocratic, that the experts weren’t actually experts, that they didn’t know what they were doing, and that they didn’t care about ordinary people.

So now the task is to clarify that what failed was not the welfare state, nor the old establishment—it was a new group who came in, believing the establishment was inefficient and trying to dismantle the State. In some ways, returning to the State as a source and defender of public goods does not take us back to neoliberalism. It takes us further back—to the idea that the people can own the State, that the State can be democratic, and, ironically, that it can be truly republican in the sense of being a public institution that ordinary citizens own and connect to.

The Breaking of the Bureaucratic State: Can US Institutions Recover?

In ‘The Assault on the State,’ you argue that modern government is under attack. How does Trump’s presidency exemplify this trend, particularly regarding the erosion of democratic institutions and bureaucratic expertise?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: What’s happening in my country right now is painful to watch, especially for those of us closely connected to the production of expertise. I’m a university professor, and many of our students and graduate students go on to work in the federal government.

They do things like work on climate change, secure military bases against flooding, prepare for future pandemics, and test new vaccines. Even before the Trump administration, it was sometimes difficult to convince young people to join public service. Many would say, I can make more money in the private sector, or the public sector is too slow, too bureaucratic. But despite these concerns, we still managed to attract a number of brilliant young people every year who were willing to commit their entire careers to public service.

Now, that pipeline is nearly broken. At this moment, no one in their right mind would join the federal government—massive layoffs are happening, and every office is being downsized. But the bigger issue is long-term: How do you convince people that this won’t happen again? How do you get young professionals to invest years in degrees and early-career government positions when they know that the next administration could just come in and fire everyone again?

The damage is much more severe than just a single administration. The US may be the most extreme case, but we see versions of this pattern in every patrimonial system. Take the Tusk government in Poland—they’re struggling to restore trust in the judiciary and undo the changes made by the PiS party. Rebuilding state institutions is incredibly difficult. The old joke applies here: It’s a lot easier to turn an aquarium into fish soup than it is to turn fish soup back into an aquarium.

The destruction of the State leaves behind a mess that takes years, even decades, to repair. So I think we have to be very realistic about the crisis we face. This won’t be fixed with just one or two elections. Those of us who care about democratic states that provide public goods in the modern world—and I hope that’s a lot of people—will have to start with education, collective action, and actively countering this disastrous assault on institutions that truly matter.

Loyalty Is the Most Important Currency in Trump’s America

Trump frequently positioned himself against the "deep state," portraying government institutions as adversaries. To what extent do you see this rhetoric as a deliberate political strategy versus a genuine ideological stance?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: I don’t think patrimonial rulers are best understood as ideological. That’s the big difference between patrimonialism and fascism—certainly compared to Nazism. Leaders like Hitler and Mussolini had ideologies; they had visions of the future. You could say those visions were crackpot or outright evil, and certainly they were. But their argument was: We know where we’re leading this new empire—it will be racially pure, or it will be a resurrection of Roman virtue. Young people will imbibe this spirit, march in step, and be mobilized.

In contrast, patrimonialism tends to demobilize society. This was true of the old Tsarist style of rule, as well as older monarchies and other non-ideological regimes, which essentially said: Let the ruler take care of the state; it’s his personal possession—gender intended. Ordinary people, the Narod in Russian (the masses), were not supposed to have a direct connection to the state, which is the opposite of fascism and other mobilizational ideologies.

When it comes to Trump himself, there’s clearly no coherent ideology. He has shifted positions on all sorts of issues, but people make the mistake of assuming that means he has no center at all. He does—his center is that he alone can fix it. He sees himself as the anointed leader—now even believing that he is divinely chosen—to govern America’s patrimony.

The consistent theme underlying everything he does is that loyalty is the most important currency. If you’re not perfectly loyal, he will punish you. The deep state, those with expertise in impersonal legal norms, are actually "fakers" who need to be destroyed. And the US itself should be treated as the property of the ruling party, the ruling state, and, ultimately, the ruling household—namely, the Trump family.

We even see echoes of imperial-style patrimonialism here. Historically, patrimonial rulers made claims on territories that were supposedly part of their rightful domain. Putin, for example, asserts that Ukraine is inherently part of Russia. Now, with Trump, we start to see similar rhetoric—claims that Greenland, Canada, or even Panama somehow "belong" to the US. This imperialist mindset, tied to a patrimonial vision of governance, is something to watch closely.

Misinformation Thrives When ‘People Are Not Hearing Both Perspectives in Real Time’

Your studies highlight how distrust in government is often fueled by misinformation. How did Trump’s presidency contribute to this, and what long-term effects do you foresee on public trust in US institutions?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: It really is a big part of the problem—no question. Social media, the internet more generally, the decline of local newspapers, and, again, the decline of trust in the so-called legacy media have made it much more difficult to get a coherent message out. Not everybody would have agreed with it, but at least elites in local politics across each state in the US, in each major city, used to have some common points of reference.

Back in the day, it was impossible to make a completely baseless claim and have it be repeated by media outlets all over the United States. That simply couldn’t have happened because not only did you have professional journalists reporting in each locality, but there was also the Fairness Doctrine—before the Reagan administration eliminated it. Under this rule, if you made one claim, you had to allow equal space for the opposing claim.

These sound like quaint notions now, but we actually need to return to them. Restoring the Fairness Doctrine would go a long way. I don’t know exactly how you would enforce it in today’s environment, but imagine if every podcaster or news show that put out an outrageous claim—say, all the election machines are rigged—had to give equal time immediately after for someone to say, ‘Actually, there’s no evidence for that whatsoever, and the people making this claim have been thoroughly debunked.’ Right now, people are not hearing both perspectives in real time. They are only hearing their point of view, and that clearly makes rebuilding trust difficult.

One last comparative point: If you look at the history of failed democracies, it’s not just social media that causes breakdowns. Weimar Germany famously fell into extreme party polarization, leading to a situation where budgets couldn’t be passed, and the political deadlock ultimately created the conditions for autocracy and Nazism. And all of that happened well before social media or the internet.

So, while misinformation and echo chambers exacerbate these crises today, they are not the only ways societies break down. However, once polarization takes hold, and each side of a divided society finds its own media outlets to reinforce its perspective—while completely distrusting all others—then it becomes incredibly difficult to restore public trust in government institutions.

Putin Is the Starting Point for the 21st-Century Wave of Patrimonialism

You discuss the global assault on modern governance. In what ways did Trump’s administration mirror or influence similar movements in countries like Hungary, Brazil, or the UK under Brexit leadership?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: The question of where it began is part of our book, and we make a claim that people found hard to believe but that we really stand by: it started with Putin.

We argue this partly through chronology. If you look carefully at the evidence before the rise of Putin in 2000 and the decades after, you had populism, of course—as you know better than anyone. There were plenty of populist movements in Europe, and they would rise on the far right or far left. They would sometimes gain parliamentary representation and make coalition-building difficult, but they never formed governments.

They were either systematically excluded from governance by pacts among mainstream parties, or they simply never achieved the electoral success to do so. The one breakthrough before Putin was Berlusconi and Forza Italia, where he briefly became Prime Minister in the 1990s. But his quick loss of power proves the rule—only after 2000, with a very close alliance with Putin, did Berlusconi’s leadership begin to take on more familiar patrimonial features.

So we place a lot of emphasis on Putin’s example. We think this is both emulation and direct support. It’s true that the Putin regime has funded pro-Russian parties worldwide, particularly in Europe. They have also pushed disinformation campaigns that serve the interests of the Russian Federation and its increasingly imperial ambitions.

Take Brexit, for example—the UK Parliamentary Commission concluded that Russia’s role in disinformation mattered in the referendum. Moscow has not been passive in this process. But beyond that, we argue the biggest factor was people simply looking at Putin’s model and realizing: "It never occurred to us before that you could build a 19th-century-style state in the 21st century—but look at what this guy has done."

People thought Russia was finished. To quote a famous 2001 headline, Russia was seen as a laughingstock. International relations realists ignored it. And yet, Putin managed to reassert Russia as a great power, influencing global events—from Syria to US elections. Those who hated the liberal center, mostly on the right, but also some on the left, began saying: "Whatever’s going on in Russia, we need to figure it out. This guy has proven we no longer have to listen to the experts. We can beat the technocrats. We can restore traditional forms of machismo, religious veneration, and hierarchy."

This emulation factor was very direct—for Orbán, for Netanyahu, and many others. These are empirical links, not speculation. People were surprised by our argument at first. But now, with recent events—including Trump’s presidency and the invasion of Ukraine—more people are asking us: "Did you really say Russia was the starting point for this?" Yes. That’s exactly what we said.

Patrimonialism Is Gaining Momentum—How Do We Stop It?

Even after his presidency, Trump’s influence may remain strong in shaping Republican politics. Do you see the attack on modern government as a continuing movement, and how might a second Trump term escalate these trends?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: I’m hoping when you say ‘a second Trump term,’ you mean this one—not the one that would come after. There’s already a lot of talk about amending the Constitution in the United States or reinterpreting it in a way that would allow him to serve beyond this term. This is very reminiscent of discussions in Russia in the 2000s, when Putin had to circumvent the official two-term limit in the Russian Constitution—first by installing his Prime Minister and then by changing the Constitution to allow himself to rule indefinitely.

These kinds of discussions matter for your question because, ultimately, these leaders must first be defeated before we can talk about reversing these trends. As long as they remain in power, the patrimonial style of governance will continue to be a dominant force—as everyone in the world can now see.

This is especially problematic when even China under Xi Jinping, while still a Leninist state with Leninist institutions, is increasingly taking on patrimonial features—with Xi posing as the father of the nation and asserting patrimonial rights to territories around China.

When China, the United States, and Russia—and to some extent Turkey, India, and Brazil—all lean in this direction, it becomes extremely challenging for the Macrons, the Scholzes, and the Starmers of the world. The remaining leaders who support modern democratic institutions are now struggling to figure out how to protect what’s left. So, the immediate problem is simply figuring out how to win in an increasingly lopsided world where patrimonialism is gaining momentum.

The longer-term challenge, which we discussed earlier, is about rebuilding a vision for the future—one that defends a modern, liberal state in the US (though, ironically, you can’t even use the word "liberal" anymore without it being dismissed as leftist radicalism or Marxism).

There is an enormous rhetorical and mobilizational challenge ahead—convincing ordinary citizens to resist these trends by making the case that patrimonialism doesn’t serve their public welfare. It doesn’t create a fair society. It fosters corruption, undermines integrity, and ignores public opinion. All of these principles—fairness, accountability, and good governance—depend on the survival of the modern state. Now is the time to spread that message.

The State Itself Is Under Assault—Democracy Comes Next

And lastly, Professor Hanson, if modern governance is indeed under siege, what steps can be taken—either by policymakers, scholars, or civil society—to rebuild public trust in democratic institutions and counter the assault on the state?

Professor Stephen E. Hanson: We were beginning to speak about this, and it’s the question that we all really have to engage with together.

We end the book by saying that proper diagnosis helps on its own. One of the key steps is simply getting people to understand that it is the state itself that is under assault—and, in the longer term, democracy as well. Because if you don’t have a modern state, you eventually can’t run free and fair elections. You don’t have the impersonal procedures necessary to count votes fairly. Instead, you end up with what you see in Russia—political pressure to produce vote totals that show the leader receiving 90% or 80% of the vote, or some other absurd outcome. And that isn’t democracy. So, we are absolutely not saying that democratic erosion isn’t a problem—it is a serious problem. But it is a longer-term issue. The immediate, short-term problem is the destruction of state capacity—something that is already happening in the US and other places as well.

So, what can we do about it?

- Diagnosis – The first step is recognizing that this is a political issue that must be tackled directly.

- Reviving Public Service – The second is getting people to care about public service as a legitimate and worthwhile career—which is incredibly difficult these days, as I mentioned earlier, given the material concerns of young people. But, at the same time, I see many students at William & Mary every day who genuinely want to do good in the world—who want their lives to be dedicated to service.

And the truth is, there are many people like that around the world—especially in modern democracies—who would agree that if we don’t have the institutional capacity to deal with climate change, the next pandemic, immigration, or any number of existential global threats, then we simply won’t be able to solve them. As a species, we will not succeed.

So, I think another crucial step is getting the rhetoric right. Instead of constantly accusing patrimonial leaders and their supporters of being anti-democratic, which only alienates their voters, we should frame the argument differently. If you tell Trump voters, “Trump is an anti-democrat, and you’re an idiot for supporting him,” they will naturally reject that. They will see it as just another elitist telling them what to think—which only fuels the cycle of resentment. But if you frame the issue as “What’s happening is the destruction of the state’s ability to do good in the world,” you can actually win people over.