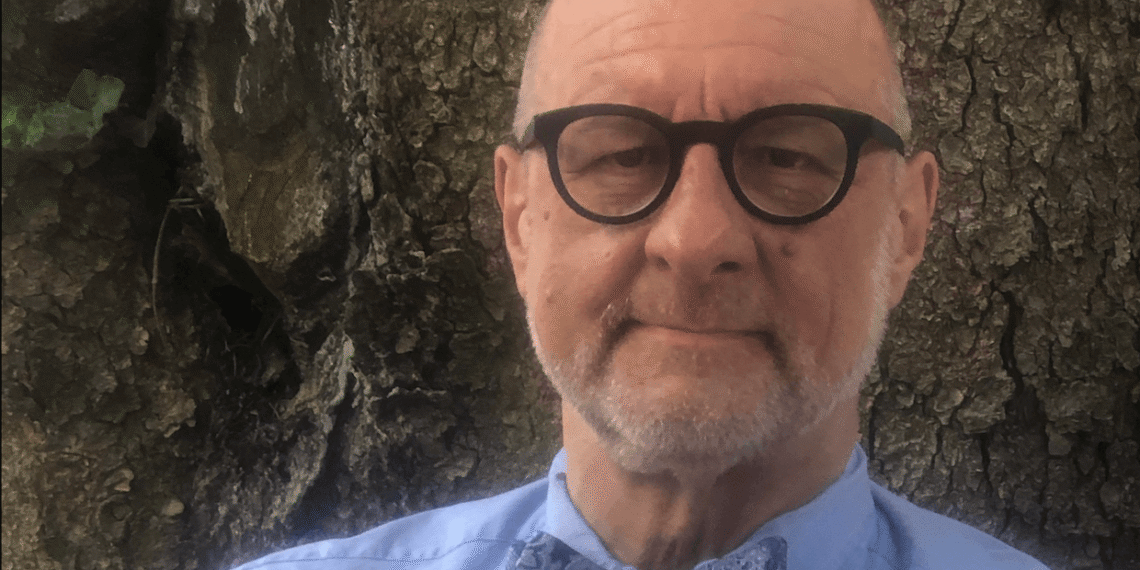

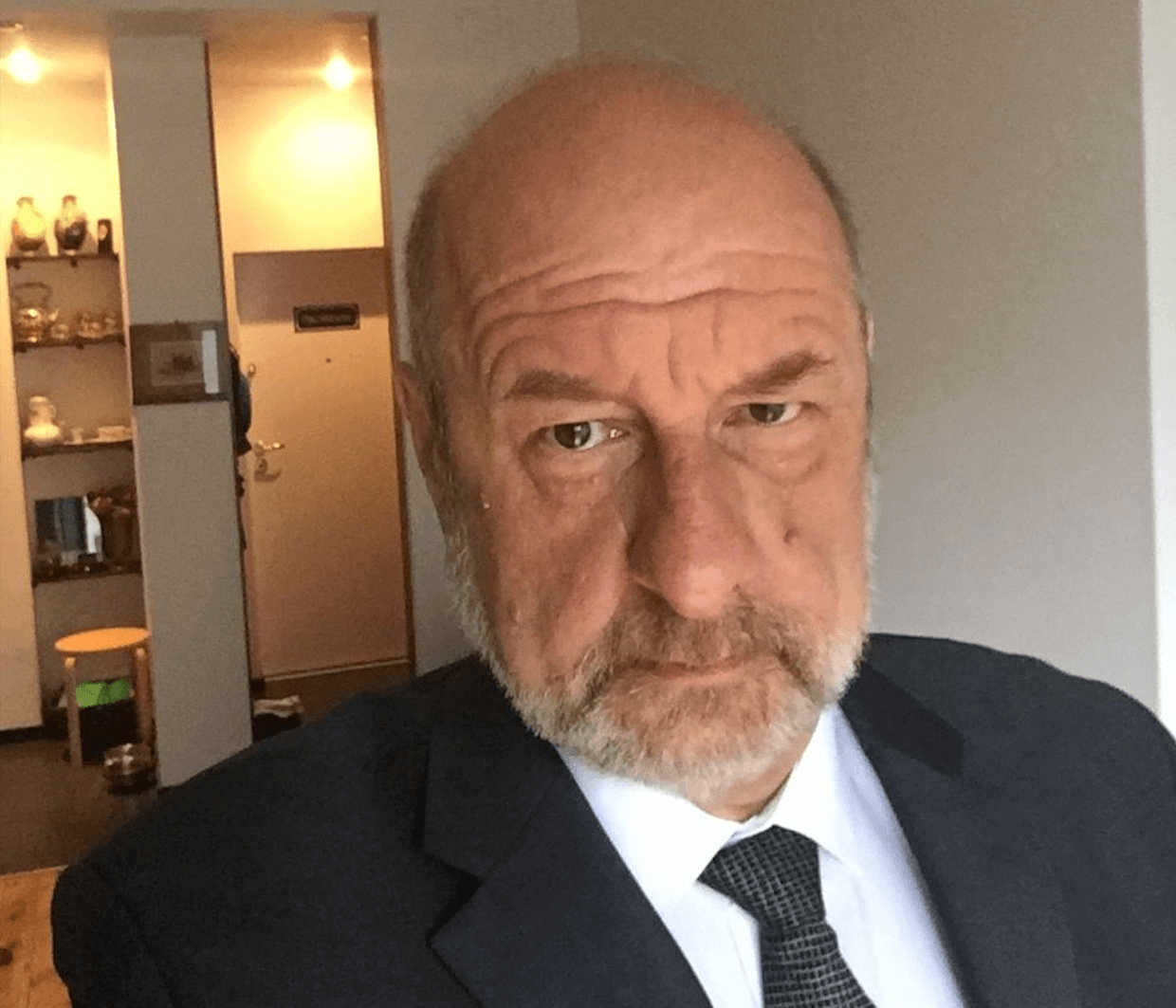

In a compelling interview with ECPS, Professor Jan Kubik challenges one of the most persistent assumptions about Central and Eastern Europe: that right-wing populism is primarily a legacy of communism. Instead, he argues, its roots lie in far older social hierarchies. “Many people say populists are stronger in East-Central Europe because of communism. I think that misses the point. It is much deeper. It is actual feudalism… long before communism,” he explains. Professor Kubik outlines how these deep-seated structures—traditional authority patterns, weak middle classes, and historically delayed modernization—interact with neo-traditionalist narratives deployed by parties like PiS and Fidesz. The result, he warns, is a durable populist ecosystem requiring both organic civic renewal and, potentially, a dramatic institutional reset.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In this wide-ranging and analytically rich conversation, Distinguished Professor Jan Kubik—a leading scholar of political anthropology and Central and Eastern European (CEE) politics—offers a profound rethinking of the foundations of right-wing populism in the region. Drawing on insights from two major European Commission–funded projects, FATIGUE and POPREBEL, Professor Kubik challenges one of the most enduring explanations for the region’s democratic backsliding: the legacy of communism. Instead, he underscores that the roots run far deeper. As he succinctly puts it, “Many people say populists are stronger in East-Central Europe because of communism. I think that misses the point. It is much deeper. It is actual feudalism, in a sense, and the structural composition of these societies… which started forming long before communism.”

The interview traces how this neo-feudal inheritance—characterized by hierarchical authority structures, traditionalist cultural norms, and weakly developed middle classes—interacts with the neo-traditionalist narratives mobilized by contemporary right-wing populists. Professor Kubik describes neo-traditionalism as a deliberate attempt to revive or manufacture tradition, often through cultural engineering, to legitimize a new political–economic order. In this context, parties like Fidesz and PiS sacralize national identity through education, religion, heritage, and memory politics, exploiting societies in which, as he notes, “authority is… male-chauvinistic… and that person simply belongs there… because this is how it is.” These deeply rooted cultural logics, he argues, help explain why symbolic interventions resonate so powerfully in Poland and Hungary, but far less in an urbanized and secularized Czech Republic.

Professor Kubik also provides conceptual clarity on the interdependence of political and economic power in right-wing populist regimes. POPREBEL identifies a “neo-feudal” regime type marked by weak business actors, strong political actors, and legitimation through neo-traditionalist, anti-market narratives. Programs such as Poland’s 500+—which “dramatically reduced childhood poverty”—are not merely economic interventions but cultural–political tools for consolidating authority.

A significant part of the interview concerns the durability of these systems. Professor Kubik warns that entrenched cultural substructures and polarized value systems make right-wing populism unusually resilient. This resilience is reinforced institutionally through the capture of courts, media, and cultural institutions—producing distinct patterns in Poland, Hungary, and Czechia.

Finally, the interview concludes with a discussion of democratic renewal. Professor Kubik’s twin proposal combines “organic, society-wide work”—especially civic education from an early age—with, on the other hand, “a dramatic institutional reset.” While the latter may sound radical, he argues that moments of deep crisis sometimes require systemic reinvention, citing Charles de Gaulle’s 1958 constitutional overhaul as precedent.

Taken together, Professor Kubik’s insights offer a compelling and ambitious reframing of populism in CEE—not as a post-communist aberration, but as a twenty-first-century expression of far older structural legacies.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Jan Kubik, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

Two ‘Neos’ That Define a New Populist Order

Professor Jan Kubik, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: Neo-traditionalism and neo-feudalism feature centrally in your recent work. How do these concepts refine or challenge the dominant ideational and strategic approaches to populism, and to what extent do they constitute a genuinely new regime type in Central and Eastern Europe?

Professor Jan Kubik: First of all, thank you for having me. I’m delighted to be able to share some of our work. As for the question, this project really emerged through a dialogue between our regional expertise and broader theoretical debates. When I began the project, I was directing the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at UCL in London, and when we were writing the grant, we were approaching it explicitly from the perspective of Central and Eastern Europe. At the same time, several of us were already immersed in the literature on populism, so the project developed—perhaps in the best possible way—through a conversation between theory and deep regional knowledge.

From the very beginning, like many others, I was fascinated by the question of what drives these developments: is it culture or economy? A number of major studies suggested that both matter, but that cultural factors seem somewhat more decisive—people often felt their worlds were being disrupted or threatened by modernity. Importantly, it wasn’t only those in dire economic straits; sometimes people who were economically comfortable still felt profoundly unsettled.

So, we were always thinking about how to combine these elements. I come from anthropology, trained in both symbolic and economic approaches, so I’ve always believed we need explanations that are complex—multi-factoral but not overly complicated.

We then began looking closely at tradition as a key resource for right-wing populists and came across the concept of neo-traditionalism. We took this to mean two things: first, the revival of a tradition that had been lost or weakened, and second, the deliberate top-down manufacturing of tradition—less organic than is often assumed, involving a form of cultural engineering.

As the project developed, we brought in a group of economists from Corvinus University in Hungary, and we began studying Hungary as an extreme case of tight interdependence between political and economic actors. This soon led us to literature on neo-feudalism. Suddenly we had two “neos”—a nice symmetry, as it turned out—and then the idea came together.

I’ve always been interested in legitimacy: how systems, including economic ones, are justified through cultural constructs. And we had a kind of eureka moment: neo-feudalism describes a specific arrangement of political and economic power, and neo-traditionalism is what legitimates it—a deliberate revival or construction of national tradition. In Poland, for example, this is deeply intertwined with a particular vision of Catholicism.

Hungary and Poland were especially valuable cases because right-wing populists were fully in power, allowing us to observe what they actually do once governing. The Czech Republic offered a different configuration—populist, but less aggressive and often described as “technocratic populism.”

So, drawing on what I know best, these three countries form a sort of analytical triangle. And that, in brief, is how the project took shape.

Culture Is Built—But Never Free From Material Conditions

Your framework draws on “embedded constructivism” and Weberian cultural–materialist analysis. How does this interpretive tradition alter the way scholars should conceptualize the relationship between populist discourse, historical memory, and everyday meaning-making among citizens?

Professor Jan Kubik: I come from anthropology, and I studied sociology and even some philosophy in Krakow before I left for the United States. I’ve always been a constructivist, but I have continually tried to understand more deeply what is really meant by that. The idea, of course, is that humans create those entities we then take for granted as natural—nations, genders, ethnicity, and all those things, including populism in some sense. And that’s fine, but I always had a kind of residue of materialism. Perhaps my studies of state socialist systems and the political economy of state socialism—which I even taught for a while—made me sensitive to the economic dimension. It is obviously central to human societies.

Weber was also a lasting influence, and he was always stretched, as he put it, between explanation and interpretation, which I found important and evocative. Eventually, I came across—or perhaps coined—the concept of being a “materialist constructivist,” based on reading other scholars. The idea is clearly present, for example, in the work of Michèle Lamont, the Harvard sociologist. When she writes about differences between working-class cultures in the United States and France, she reminds us that while we may be focused on culture, we cannot forget the material base of the situation: different economic systems, different types of capitalism, and so on.

So, I thought, yes, this is exactly what we want to do as well. Our expertise—except for our economic colleagues—is mostly on the cultural side, but we should never lose sight of the economic dimension. This concept is simply another way of bringing those two elements together.

Polarized Subcultures as Engines of Persistence

In your POPREBEL conceptual architecture, you rely on three analytical oppositions (supply/demand, culture/economy, challengers/incumbents). How do these axes interact in explaining the durability—not merely the rise—of right-wing populism in CEE?

Professor Jan Kubik: Here, I am still a bit on thin ice. We are not fully there yet, but it is a great question—thank you for it. I don’t think I have ever articulated it so clearly to myself as you just did. But here are my hunches, based on several years of work—so these ideas may evolve, but for now I would say this: There is much more to be done on the demand side. There are cultures or subcultures in these societies that are conservative, traditional, traditionalist—however you would call them. And the supply side consists of political entrepreneurs, activists, intellectuals, and even some artists who lean conservative and at some point realize: oh, society is not entirely liberal, left, or centrist—there is a huge chunk of people who will listen to us because they already think this way, more or less spontaneously, due to historical circumstances.

So, I would say that this existing demand, these existing subcultures, indicate a certain durability of the phenomenon. Once this process gets going, it may be more difficult to change than we assume. In practice, this means that in Polish society—and to a large degree in American society as well—you have tremendous polarization. What emerges from this culture war is more polarization. We may be stuck with societies polarized not only politically but also culturally, at a deeper level. That is the key factor on the demand side.

Culture and economy I already explained, so I will just add that because the question of legitimation is at stake, cultural mechanisms need to be carefully observed. Whenever right-wing populists come to power—this is empirically clear—they are interested not only in taking over elements of the political system, such as the judiciary, but also in controlling institutions of cultural production: school programs, museums (I have done a lot of work on historical memory and museums), and not only historical museums but all kinds of them. They try to control theater productions, and they move into film production to ensure that more “patriotic” movies are created, and so on.

As for incumbents versus challengers—yes, we need to examine both, but for us, incumbency is crucial because in our region we have the best cases of these political formations holding full political power. We can actually observe what they do once in office. In other places, throughout Western Europe and elsewhere—India may be somewhat similar—you have parties entering coalitions and sometimes mellowing down, as observers say is happening with Meloni: once in government, she tones things down a little. Orban did not tone anything down, nor did Kaczynski. Modi does not tone down much.

Then there is Brazil, a fascinating case, because Bolsonaro never managed to get control over the judicial system—particularly the Supreme Court—which produces an interesting and somewhat scary parallel with the United States, where the court is not at the end of a telephone line from the White House, but is, everyone would agree, much more sympathetic to the president than it was under previous administrations.

Populism as a Product of Long Cultural Trajectories

In “Populism Observed,” you argue that Czech and Polish populisms are “tantalizingly different.” To what extent do these divergences stem from long-term political-cultural trajectories as opposed to variations in political agency, party organization, or media ecosystems?

Professor Jan Kubik: This is my favorite part of the project at the moment, because of my interest in history and the fact that I see myself as a historical institutionalist, so I always want to understand longer trajectories—how different institutions or cultures and subcultures emerged over time. I also have some personal links: my mother was born in Prague, and my great-grandfather was Czech, so I always felt somewhat comfortable between Czech and Polish cultures, and now I have a chance to work on it more systematically.

When you dig into the basic trajectory—and the main interest for us, because we accept, as you said, the ideational definition of populism—the thing of great interest, starting from the Polish side, is the role of religion, in this case Catholicism. But when you cross the mountains to the Czech side, you are in a completely different reality, going back to the 14th and 15th centuries—five centuries of a completely different trajectory in the interaction between religion and other cultural and political factors, mostly because of Hussitism and Jan Hus, a kind of proto–Martin Luther about a century earlier. This sets the whole field of what I call national self-understanding—who are we as Czechs versus who are we as Poles?—on very different trajectories over time.

The story is more complex, but every bit of evidence we look at adds to the picture. I am a believer in falsification—I would be happy to find evidence that contradicts my hypothesis—but almost everything falls into place, one bit after another. A quick example: in the Polish case, Romanticism in the first half of the 19th century is central. Poland is partitioned, disappears from the political map, and everyone agrees that Romanticism is at the center of Polish self-understanding: the heroic imagination, always fighting, always on the barricades, having a mission—messianic or, as one of my professors called it, “missionic”—the idea that we can save Europe from itself. Kaczynski says such things: that true Catholicism exists in Poland, that the West is decadent and has forgotten its true roots in Christianity, and that Poland can rescue Europe from itself. There is nothing like that in the Czech case.

The Czech trajectory leads to, in two words, more moderation and stronger liberalism. So, Babiš, the Czech populist who is back in power again, is much more restrained. He is much more attuned, shrewd in that sense. He is a good politician; he knows he cannot go too far. He cannot go as far as Kaczynski or Orbán and remain credible. I think he understands that will not work. And just two days ago, one of my Czech colleagues sent me a short Czech text—an interview with Orbán, who said something like: Look at the Czechs; they are less crazy than we Hungarians, but they also have doubts about supporting Ukraine. The first part of the sentence shows that Orbán recognizes that these more sober-minded Czechs also share some positions with him, but it comes from a very different cultural background.

Why Czech and Polish Populisms Reshape Institutions Differently

Your analysis highlights the personalistic nature of Czech populism (embodied by Babiš) versus the ideational, party-driven nature of Polish populism (PiS). How do these distinct modalities shape patterns of institutional transformation, particularly in relation to state capacity and judicial independence?

Professor Jan Kubik: I can only say something about correlations—and yes, we keep reminding our students that correlation is not causation. I do not understand the mechanism, honestly, yet. But if you observe that the Polish judiciary is decimated and cannot recover even now, two years after the defeat of PiS, there is no good way of doing that. I follow the debates among scholars of the law, activists, and people who are now in charge of the legal part of the system in the new government. And still the Supreme Court, to some degree—and the Constitutional Tribunal completely—are controlled by PiS appointees. You hit that famous dilemma: should we use undemocratic methods to undo damage to democracy done by undemocratic forces? The idea is that maybe we shouldn’t, because then we behave like them—and so on; this is a well-recognized dilemma. In the Czech case, Babiš never attacked, never tried to take over the courts. He did attack them rhetorically, but he didn’t create anything like the situation that exists in Hungary, where Orbán completely controls them, or in Poland.

So, the one thing that I can say is that now that we have quite a bit of data, one thing I know for sure is that Czechs think about the map of the political, socio-political reality in very personalistic terms. In our analysis, in Poland, Jaroslaw Kaczyński doesn’t come up, even. You have to be a bit of an expert—everybody in Poland knows—but people seem to accept his preferred way of existing in the public domain, which is behind the scenes. So, in the Polish case, it is, as you said, PiS—the Law and Justice Party—that people associate with the center of the system. And then you see this difference in the situation when it comes to, say, the judiciary.

I don’t know what the link is. I just observe that this is how the two systems are different. Maybe the answer is simply that the reformist program of Polish right-wing populists is more ambitious and more comprehensive. The Czech project is more self-constrained. It’s a hypothesis.

Why Polish and Czech Resentments Diverge

How might the conceptual networks emerging from online ethnography and semantic network analysis help explain why anti-elite resentments in Poland crystallize around specific institutions (PiS, the Church, PO), while in Czechia they coalesce around abstract concerns such as manipulation or state incompetence?

Professor Jan Kubik: This analysis is based on about 140 very long interviews in Czechia and in Poland. We use this sort of custom-made method of semantic network analysis, which allows us to create visualizations of networks of concepts, with the intensity of connections marked. This method was developed in collaboration with mathematicians, and it was a great kind of multi-method situation where they were saying, “Look, we know how to do those abstract things, but we need to know the context.” It was really refreshing to hear that from mathematicians: you are the experts on the region; we have to keep going back and forth between the data, your reading of the interviews in the original languages, and our modeling. So, this was great, and that is the product of it.

If I go back to the interviews: in both the Czech and Polish cases, one thing that is very clear is that people’s concerns are, to a large degree, divorced from the heated, polarized political–ideological war that we often observe on the front pages of newspapers—observed by people coming from abroad or even internally by those who study these things. From what we got in our interviews—and here is the very important thing—we didn’t ask, “What do you think about X?” or “What do you think about Kaczyński?” or “What do you think about populism?” Nothing like that. We assumed we would talk about life and see what comes out organically. Eventually, we decided to tighten it a bit, and the slogan organizing the interviews was well-being, which very quickly led people to talk about problems. And I think it’s very useful. We don’t tell them how something is related to populists or not. Then sometimes it pops up—whether populists can help them or not.

But what comes across is this pervasive sense that the state—its institutions, particularly when it comes to healthcare—is very, very poor. The service is very poor. People are very unhappy. And they are unhappy across the board with every political formation in some cases—quite a few of them. They look critically at the previous government, Donald Tusk’s government (which is now back in power). They look critically at PiS’s government. They seem to be very much concentrated, as people have observed from time to time in other studies, on their everyday problems.

I was thinking about what happened in the United States now, with that Democratic wave a week ago or so—particularly Mamdani. He was so effective because he talked to people about everyday problems. Affordability. That was very much what we found in those interviews.

So, at this point, I’m thinking—because this analysis is not closed; the project is still in progress—that there is an interesting disjoint, some kind of discrepancy, between the layer of national political discourse and what is really in people’s heads, what really bothers them. And there are, of course, moments of connection, and there are some influences, but the most striking feature for me is this disconnect between those two layers of culture, however you would call it.

Mapping the Political–Economic Fusion Behind Populist Power

The POPREBEL work suggests that right-wing populist regimes fuse political and economic power in a neo-feudal pattern. How does this pattern differ from classical patronalism in post-communist states, and what empirical indicators best capture it?

Professor Jan Kubik: Let me go into a bit of splitting hairs, because I’m very proud of this. This is not me; this is our colleagues—economists, particularly one, István Kollai, but also others. I was involved, though; those were fascinating discussions.

We started with the basic idea—there is a huge literature on the relationship between the business or economic domain and the political domain. So, we started with the basic logical typology: you have the situation where business is dominant and politicians are subordinate; you have the situation where they are equal; and then you have the situation where it is the other way around. So those are the three possible types.

Then we looked at—and this is what the economists came up with—the second dimension, which you can describe as the form of legitimacy. So again, what returns is this kind of culture–economy combination. And they divide it into three again. There is the kind of secretive private interest—there is no effort to produce any form of legitimacy by whoever is in power. Second, there is the situation where there is justification through invoking market competitiveness, which is a kind of neoliberal solution or developmental state, or something like that. And then the third one is legitimacy through, by and large, neo-traditionalism combined with anti-market—what they called anti-market counter-movement.

And this you see clearly in Poland with Kaczyński, where they increased their distribution dramatically, this famous program, 500 plus for every child and then the second child, which dramatically reduced childhood poverty. So PiS has a serious success on its hands. And of course, Orbán is doing the same thing through other specific methods.

So, if you take those 3 by 3, then you generate nine types, which is maybe a little bit too much, but I don’t want to go through all of them. But here’s where feudalism, neo-feudalism, or as we sometimes call it, feudal capitalism, sits: it is weak business actors and strong political actors—one of those three types of the relationship—and legitimation is through neo-traditionalism and counter- or anti-market movement.

You can imagine that if you look logically at those nine cells, you will have different combinations of those features. Some are purely abstract, logical categories, but some are very much in existence. Just one more example: if you have strong business actors and weak political actors and a secretive tendency toward private interests, this is what is often called crony capitalism.

Why Insecurity—Not Inequality—Fuels Populist Appeals

How do you interpret the interplay between economic insecurity (transition fatigue, inequality, regional dualization) and the moral/cultural appeals mobilized by right-wing populists? To what extent is the economic dimension still under-theorized in populism studies?

Professor Jan Kubik: Yes—this first emerged in our discussions across the whole team, which ranges from economists to people doing theater studies and similar fields. Again, the significance of cultural production came up repeatedly. And also resistance to thriving populists often comes through cultural institutions.

It actually came from the economists first that much of the economic interpretation of the rise of right-wing populism focuses on inequality. They quickly said, early in the project, that we need a concept broader than that. We do not deny the significance of inequality, but insecurity is a broader concept. Insecurity can be generated by malfunctioning political institutions, or the perception that institutions are malfunctioning, or certainly by invoking cultural fears. What is interesting is that economists—not only our economists, but others studying these phenomena—are increasingly taking seriously not just material interests, but also interpretations of the world. The stories about the world matter.

So that’s when the concept of insecurity emerged, and right-wing populism enters with its story of neo-traditionalism. A story many people tell—it’s just that ours uses slightly different words. This is the story that if we go back to our genuine culture, back to our roots, we will make our country great again. We will return to our normal state of being. It was disrupted by liberalism, by modernization, by ideas about gender equality, equality for LGBTQ+ people, the existence of more than two genders—all of this.

You can clearly see the reactions to those developments. The return to “two genders”—the president issuing a document declaring that there are only two genders, against everything we know from anthropology, my own discipline. Many cultures clearly recognized more than two genders. And I don’t even know what to do with that. Because in American universities today, people get fired for saying the president may be wrong on that.

So, yes, bringing back traditions to increase security—that’s the essence. Again, it’s not very original; many have noticed it. But we are trying to show how it works in some detail.

Deep Social Hierarchies—not Communism—Explain Populist Resonance

Your chapters on education, religion, and heritage document a systematic attempt by populists to ‘sacralize’ national identity. What structural conditions allow these symbolic interventions to resonate so deeply, particularly in Poland and Hungary?

Professor Jan Kubik: By structural conditions we mean a certain state of society. I see pretty strong differences between Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. So, let’s put the Czechs aside quickly, because this is the society that is most urbanized and among the most secular in the world, which has a historical explanation. Structurally, this is a society with many people who do not belong to any organized religion and who are situated in the middle range of the class structure. It’s a very middle-class society—by and large. It is a little bit like England. You don’t have those classical East European landscapes of very poor villages, but rather a lot of small towns—little urban spaces—a bit like England, which, of course, has its historical roots.

And then in Poland, you have a very different story. Until World War II, this was a very peasant society, and then you have an enormous change in social structure after the war with the total elimination of the Jews, who were important in the middle range of society, and the movement of the country 300 kilometers or so to the west, and then the influx of many people from the east—more of a peasant society. Long story short, some sociologists use the term peasantism or neo-peasantism, which I take as an anthropologist and sociologist to mean attachment to a specific, rich, but distinct culture based on, for example, a very different notion of authority. That authority is kind of male-chauvinistic; “samodzielny” (autocrat) is usually the man at the center—like in extensive kinship systems—at the top of the local social pyramid. And that person simply belongs there. If you ask people, “Why is this person there?” the answer is, “Because this is how it is. This is how things should be.” So, it is a very different idea than the liberal one. In Weberian terms, it is traditional versus bureaucratic, instrumental, or rational. Liberal democracy is based on transparency, clear criteria. It’s boring, dull, mechanistic—but it is a system that generates much more accountability and transparency. In this traditionalistic system, no, this is not the concern.

And if you describe it like that, it is very close to the populist idea of the volonté générale. Once you recognize what people want, and you are with them—one of them—then that’s it. A few more steps, and we are in paradise.

In Hungary, the way I understand it, it is somewhat similar to Poland, but there are studies showing that during the interwar period, Hungary was strongly leaning fascist. It had a very strong fascist movement—also in Poland, but not as strong. Studies show a very strong tradition in the countryside. Hungary is also very polarized: you have the massive agglomeration of Budapest—very urban culture—and then countryside with a few smaller towns. And that culture is somewhat similar to the Polish culture of traditionalism, traditional forms of authority, traditional gender norms, and so on.

So, that’s the structural precondition. Many people say populists are stronger in East-Central Europe because of communism. I think that misses the point. It is much deeper. It is actual feudalism, in a sense, and the structural composition of these societies, historically, which started forming long before communism. If modernity is defined by the emergence of a middle class and specific upper classes—experts, specialists, bourgeois layers—all of this came to this part of the continent much later than in the West. And that happened much earlier than communism.

Renewal Requires Both Organic Education and Institutional Reset

And lastly, Professor Kubik, in your forthcoming work on countermeasures, you discuss possible remedies for democratic erosion. What forms of democratic renewal—institutional, economic, or cultural—are most promising in reversing neo-feudal and neo-traditionalist tendencies in CEE?

Professor Jan Kubik: The Anatomy of Right-wing Populists was based on the work of 15 doctoral students who we trained in the program. So, this is something we’re proud of—that there’s a younger generation of scholars working through this. That final chapter in the book comes from their work.

But in brief, I think there are two main avenues of reform or re-democratization. One is—and no matter how I approach it, I always end up in the same place—education. But then the question is, what kind of education? Well, civic education, and it needs to be organic. My obsession is that “organic” means really embedded in society, with a lot of people engaged in it, and it has to start early. My wife teaches kids at various levels, and she always tells me that the kids are very attuned to descriptions of social justice, democracy—they have a sense of fairness. There’s fertile ground for teaching the basics of democracy very early on. But that requires a large, massive program.

On the other hand, and at another level, you have to find a way to reform the institutions that have been damaged—maybe as quickly as possible. Poland is a perfect case. I’m trying to write about it now, time permitting. You have the Prime Minister from liberal-conservative center; that’s what PO is under Tusk. It’s a complex coalition which is a problem in itself. On the other hand, this popular right-wing populist formation. They are divided roughly as follows: the Prime Minister is a liberal democrat; the President is a right-wing populist; and the Supreme Court, along with parts of the legal system, remains dominated by right-wing populist appointees. What do you do with that after two years?

It is very difficult to change things through reform using regular democratic methods. The price you pay is a very unhappy society. Particularly women—young women—because women, and rightly so, brought Tusk to power. I mean, not only them, but they were very instrumental. They mobilized against the most draconian abortion law in the EU. And Tusk cannot do much for them, because part of his coalition is a conservative party—anti-radical populist, right-wing populist, but conservative. So, he is stuck; nothing happens. His approval rating is dismal. In some polls, it was 30% or something. It’s even lower than Trump.

And I had this somewhat crazy idea—I even tried to raise it with some people at meetings in Warsaw. It didn’t go very far, because it does sound extreme, but it came out of sheer desperation. What do you do after eight years of right-wing populist rule that has so thoroughly damaged the institutions? You have to restart the system. Begin with a new Constitutional Convention—literally reboot the entire framework. Practically, it doesn’t seem doable, but when I looked for historical precedents, I turned to Charles de Gaulle in 1958, when he shifted France from the Fourth to the Fifth Republic. It was a moment of deep crisis—the Algerian War, multiple political breakdowns—and the parliament was, in his view, ungovernable. He won a referendum decisively and created the system France has today, a strongly presidential republic. He reset the system—if the word “reset” means anything, that was it.

So, my idea is: organic, society-wide work on the one hand, and, on the other, a dramatic institutional reset. But that didn’t happen, and the system simply muddles through.