Please cite as:

Miklin, Eric. (2024). “The Populist Radical-right Freedom Party in the Austrian 2024 EU elections.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0061

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON AUSTRIA

Abstract

The only competitive populist party running in the 2024 EU elections in Austria, the radical-right Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) relied on well-proven recipes that have made it one of the most successful populist parties in (Western) Europe for the last 30 years. It called for cutting down the EU’s competences to half the size of its institutions and budget and harshly criticized its policies concerning migration, the war in Ukraine, the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. This criticism was combined with a highly alarmist rhetoric that portrayed political opponents as either corrupt, fanatical or insane. While all this met with uniform criticism by other Austrian parties and large parts of the media, this again allowed the party to present itself as the sole party actually fighting for the Austrian interest against a broken system controlled by a single establishment ‘unity party’ (Einheitspartei). Once more, this strategy paid off and the FPÖ landed in the first place for the first time in a nationwide election.

Keywords: Austria; populist radical right; Euroscepticism; anti-establishment positioning; European Parliament

By Eric Miklin*(Department of Political Science, Paris-Lodron University, Salzburg, Austria)

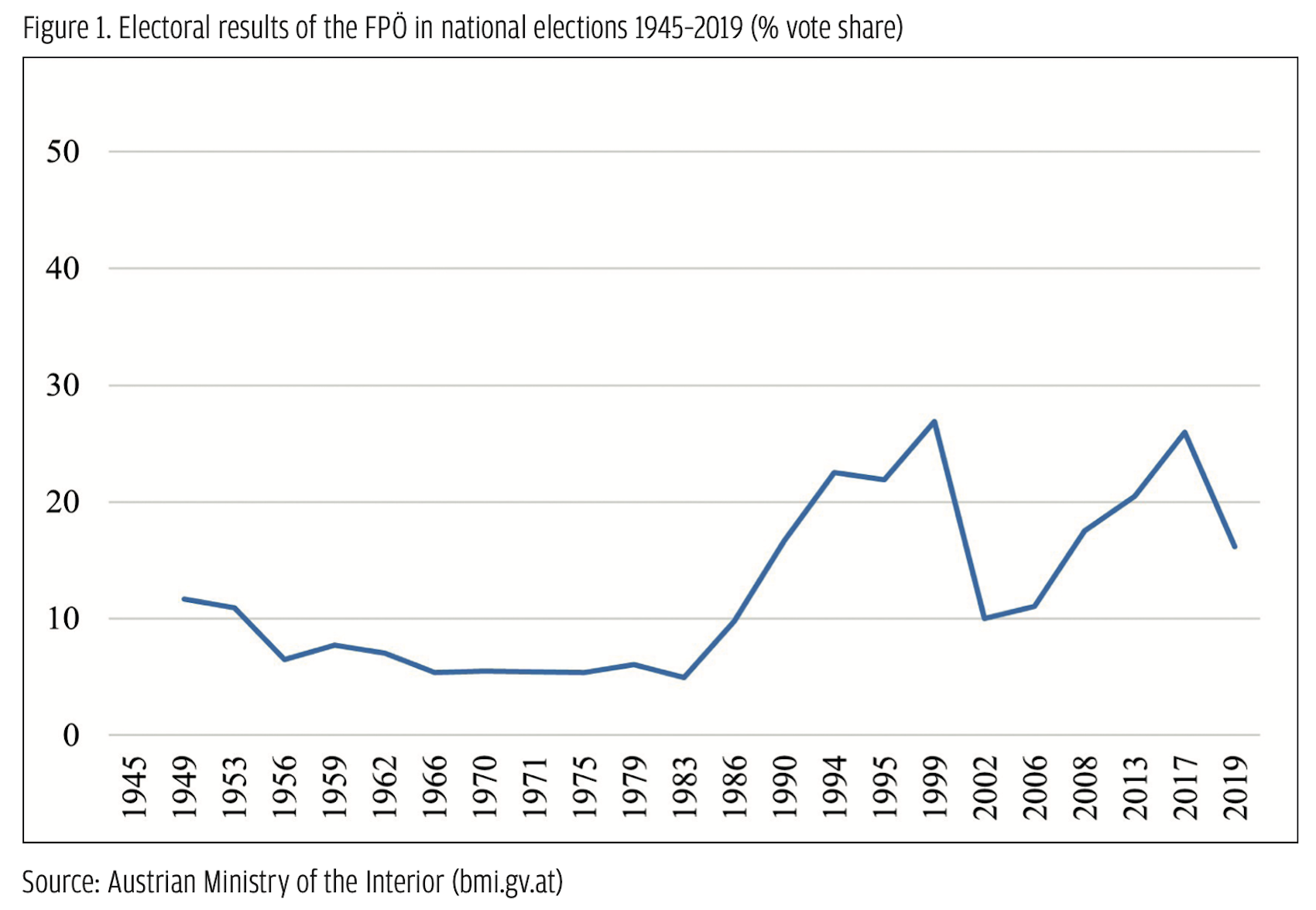

Austrian populism: The radical right Freedom Party

Populism in Austria so far has been confined mainly to parties of the (more or less) radical right. Throughout the years, several of these parties have entered the national and regional parliaments but sooner or later departed the scene. The one exception to this is the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ). Founded in 1956, it did not start as a populist party but descended from both liberal and German nationalist currents of the nineteenth century. While it managed to enter parliament in 1956 and has stayed there ever since it played a rather marginal role in the Austrian party system for the first three decades. However, this changed in 1987, when Jörg Haider was elected as party leader, transforming the FPÖ into one of the first and most successful populist radical-right parties in Europe (Heinisch 2003). Since then, the party has reached up to 27% of the vote in national elections and has not only participated in regional governments regularly but also entered national government three times (2000–2003, 2003–2005, and 2017–2019) through coalitions with the centre-right Austrian Peoples Party (ÖVP).

The party’s success has been based on a strong focus on opposing migration policies, identity politics and authoritarianism, combined with classical elements of populism as a ‘thin ideology’ (Mudde 2017). Hence, the party holds a critical stance towards liberal elements of democracy like representation, the separation of powers, the protection of minorities and basic rights. Politics, thereby, is seen as a Manichean battle between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in which the FPÖ portrays itself as the sole defender of the will of the Austrian people against corrupt (political) elites (Wodak 2005). While the fight against migration clearly has remained its core issue, the party has taken highly critical positions on measures aiming at fighting climate change or towards protective measures taken by the Austrian government during the COVID-19 pandemic (Eberl et al. 2021), among others.

Over the years, the FPÖ has gone through major crises, leading to party splits and significant electoral losses (see Figure 1). The party’s successful ‘stock response’ so far has been its further radicalization in terms of its policies and rhetoric (Heinisch & Hauser 2016), but also in terms of its proponents and their contacts with organizations that have been classified as ‘extreme right’ by the Austrian Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution like the Identitarian movement or selected German nationalist fraternities (Bundesministerium für Inneres 2023). By now, the party has also established a quite dense network with other anti-liberal populist actors like the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the French National Rally (RN), but also Vladimir Putin’s United Russia, with which the FPÖ even signed a formal partnership agreement in 2016 (i.e., after Russia’s illegal annexation of Ukrainian Crimea; Heinisch & Hofmann 2023).

During the 2024 EU elections, the FPÖ was the only populist party represented in the Austrian parliament. The only other party that might be classified as populist that ran in the elections was the Democratic, Neutral, Authentic (DNA) list led by a former physician and anti-vaccine activist, who played an active role in protests directed against the protective measures taken by the Austrian government during the COVID-19 pandemic. This party, however, was founded just months before the elections, received hardly any media- and public attention, and failed to win a seat, taking just 2.7% of the votes. The following report will therefore restrict its focus to the FPÖ.

During the 2024 EU elections, the FPÖ was the only populist party represented in the Austrian parliament. The only other party that might be classified as populist that ran in the elections was the Democratic, Neutral, Authentic (DNA) list led by a former physician and anti-vaccine activist, who played an active role in protests directed against the protective measures taken by the Austrian government during the COVID-19 pandemic. This party, however, was founded just months before the elections, received hardly any media- and public attention, and failed to win a seat, taking just 2.7% of the votes. The following report will therefore restrict its focus to the FPÖ.

The Freedom Party and EU affairs

Due to its German nationalist origins and the resulting denial of an Austrian nation, the FPÖ for decades was quite positive about the country joining the EU as a second-best option given the impossibility of a ‘reunification’ with Germany (Fallend 2008: 2010ff). It was only in 1991 when the party started to take a more critical position – which in the literature has been interpreted less as an ideological repositioning but as driven by electoral considerations of its then-party leader Haider, who in 1988 was still claiming the Austrian nation was an Ideologische Missgeburt or ‘ideological monstrosity’ (Frölich-Steffen 2004). As a result, the right-wing FPÖ, together with the left-wing Green Party, opposed Austria’s EU accession during the campaign for the required constitutional referendum in 1994. However, while the Green Party modified its position soon after the referendum had passed successfully, the FPÖ stuck to its negative position, making itself (for most of the 30 years since then) the only parliamentary party publicly voicing harsh opposition against EU integration.

In line with the FPÖ’s ideological move from German nationalism to Austrian patriotism (Frölich-Steffen 2004), its position became even more critical over time. Until today, the party has never (openly) called for Austria to leave the EU. Still, it hailed the UK’s decision in favour of Brexit and, so far, has never rejected the possibility of a future ‘Öxit’ (Bartlau 2023). Also, the party not only opposes further integration but calls for the renationalization of decision-making powers to unwind purported aberrations evoked by both the Maastricht and the Lisbon Treaties (FPÖ 2017). In its current party manifesto, the FPÖ envisages a ‘Europe of Peoples’, rejecting ‘any artificial synchronisation … through forced multiculturalism, globalization, and mass integration’. In the party’s view, cooperation within the EU must be based on the principles of subsidiarity and federalism and ‘[t]he basic constitutional principles of sovereign member states must have absolute priority over Community law’ (FPÖ 2024a).

The Freedom Party’s 2024 EU campaign

In line with this position, in its 2024 campaign, the FPÖ repeatedly stated that it would not aim for an ‘Öxit’. However, it framed the elections as a ‘referendum’ about Austria’s ‘future’ and as a choice between a ‘centralized state’ on the one hand and ‘sovereignty’ on the other (Kurz, 2024). For this to be achieved, it called for ‘the EU to shed some pounds’ (‘Weg mit dem Speck’) by halving both the size of the EU’s budget and its institutions. As the party’s front runner, Harald Vilimsky, put it: “The smaller the bureaucratic monster in Brussels, the less it is able to intervene in the lives of European citizens with ever more regulations. In contrast to what our opponents claim, we don’t want to destroy anything …. We only want to focus European cooperation on the original idea of the EU, which has long been forgotten: peace, freedom and prosperity” (Freiheitlicher Parlamentsklub 2024).

According to its electoral manifesto (FPÖ 2024b), the number of MEPs should be cut by half since even the US Congress functions with fewer members, and that, in any event, the EP does not count as a real parliament (Vilimsky 2023). Moreover, the idea brought by Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán to abolish direct elections in favour of the pre-1979 system of national MPs representing their member states was seen as ‘definitely worth considering’ by Vilismky (Kurier 2024).

Regarding policies, four topics dominated the party’s campaign: migration, the war in Ukraine, Climate change and, notably, the COVID-19 pandemic. Amongst those four, migration was the most important. The FPÖ rejected the EU’s Pact on Migration and Asylum and generally any mandatory distribution of asylum seekers across the EU. Instead, it called for a ‘Fortress Europe’ based on a ‘Pact on Re-Migration’ that should transform Europe’s human rights framework into a legal system that permits (a) pushbacks at the EU’s internal and external borders, (b) the denial of asylum to refugees stemming from non-European territory and (c) extra-territorial refugee camps, amongst others. While the Israel–Hamas war was scarcely raised as an issue, the party harshly criticized the EU’s activities in the war between Russia and Ukraine. It called for an immediate end to financial and military aid to Ukraine, as well as for the sanctions against Russia to be abolished due to their detrimental effects on the economy. While the EU was criticized for not trying to find a peaceful solution faithfully, the support for its policies by the Austrian government was criticized as a breach of the country’s constitutional obligation of neutrality.

Regarding environmental policy, the FPÖ demanded a stop to the European Green Deal, the EU Nature Restoration Law, and the scheduled ban on combustion engines. Concerning COVID-19, the party called for a ruthless elucidation of the EU’s allegedly questionable role during the pandemic. Amongst others, it demanded the disclosure of text messages sent between Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and the CEO of Pfizer, the pharmaceutical company from which the EU obtained its vaccinations (Vilimsky, 2024a). More generally, the EU’s COVID-19 policies were criticized for unjustified restrictions on individual freedoms and for having been abused to turn the EU into a Schuldenunion or ‘debt union’ (FPÖ 2024b).

The frames used by the FPÖ when pushing these claims were located mainly on the cultural dimension when it comes to questions of migration and the EU’s future development (see above). Arguments regarding global warming and the war in Ukraine were framed mainly in economic terms. The party called for Klimapolitik mit Augenmaß, namely, climate policies with a ‘sense of proportion’ regarding their economic effect. At the same time, the sanctions against Russia were criticized for hurting Austria and the EU more economically than they hurt Russia.

Generally, however, the party’s campaign was based less on arguments than on evoking negative emotions by using highly alarmist language combined with rhetoric that portrayed its political opponents on the national level – the ÖVP, the Social Democrats (SPÖ), the Greens and the Liberals – as all being part of an Einheitspartei or ‘single political party’ (Vilimsky 2024b), and EU-level actors as either corrupt, fanatical or insane. For example, on an election poster entitled ‘Stop the EU-lunacy’, a dystopic photo montage showed Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Commission President von der Leyen allegedly kissing each other intimately, surrounded by scenes entitled ‘eco-communism’, ‘COVID-19 chaos’, ‘warmongering’ and ‘asylum-crisis’ (Figure 2).

The demand side of the EU: Critical populism in Austria

The demand side of the EU: Critical populism in Austria

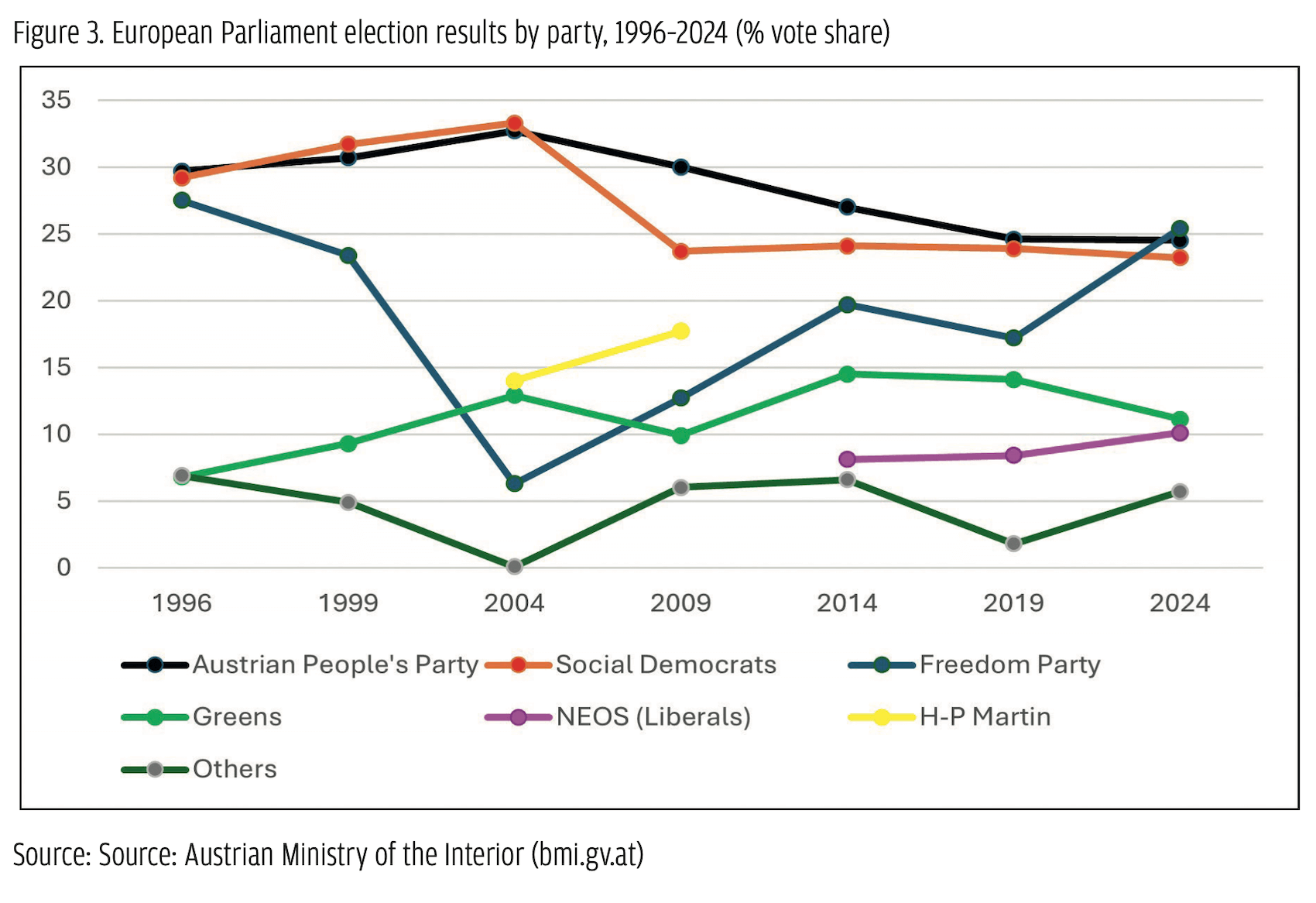

The FPÖ’s mix of issues and its communicative strategy turned out to be successful (Figure 3). First, it increased its vote share significantly compared to 2019 (it should be noted, however, that the party was hit by a huge scandal – the so-called Ibiza affair – that led to the step-down of the FPÖ’s then-party leader and Austria’s deputy chancellor, Heinz-Christian Strache and the collapse of the then ÖVP–FPÖ governing coalition just eight days before the election). Second, and more importantly, for the first time ever, the FPÖ managed to end up in first place in a nationwide election. According to exit polls, the party won votes mainly from the ÖVP (about 221.000 out of the 891.000 votes for the FPÖ) but also from about 100,000 voters who, perhaps demotivated by the Ibiza affair, did not vote in 2019 (Laumer & Praprotnik 2024). Despite the win, electoral analyses in the media interpreted the result as slightly disappointing for the party, as many polls leading up to the election had predicted an even larger victory and a greater margin over the runner-up, the ÖVP.

There are three possible explanations for this. First, the turnout rates of FPÖ supporters at EU elections have traditionally been lower than in other national elections. Second, FPÖ voters, on average, had decided who they would vote for earlier than supporters of other parties, which might have led to biased polling results. Third, the second ‘populist’ party running for election, DNA, in many regards, focused on similar issues and hence provided an alternative to protest voters who otherwise might have opted for the FPÖ.

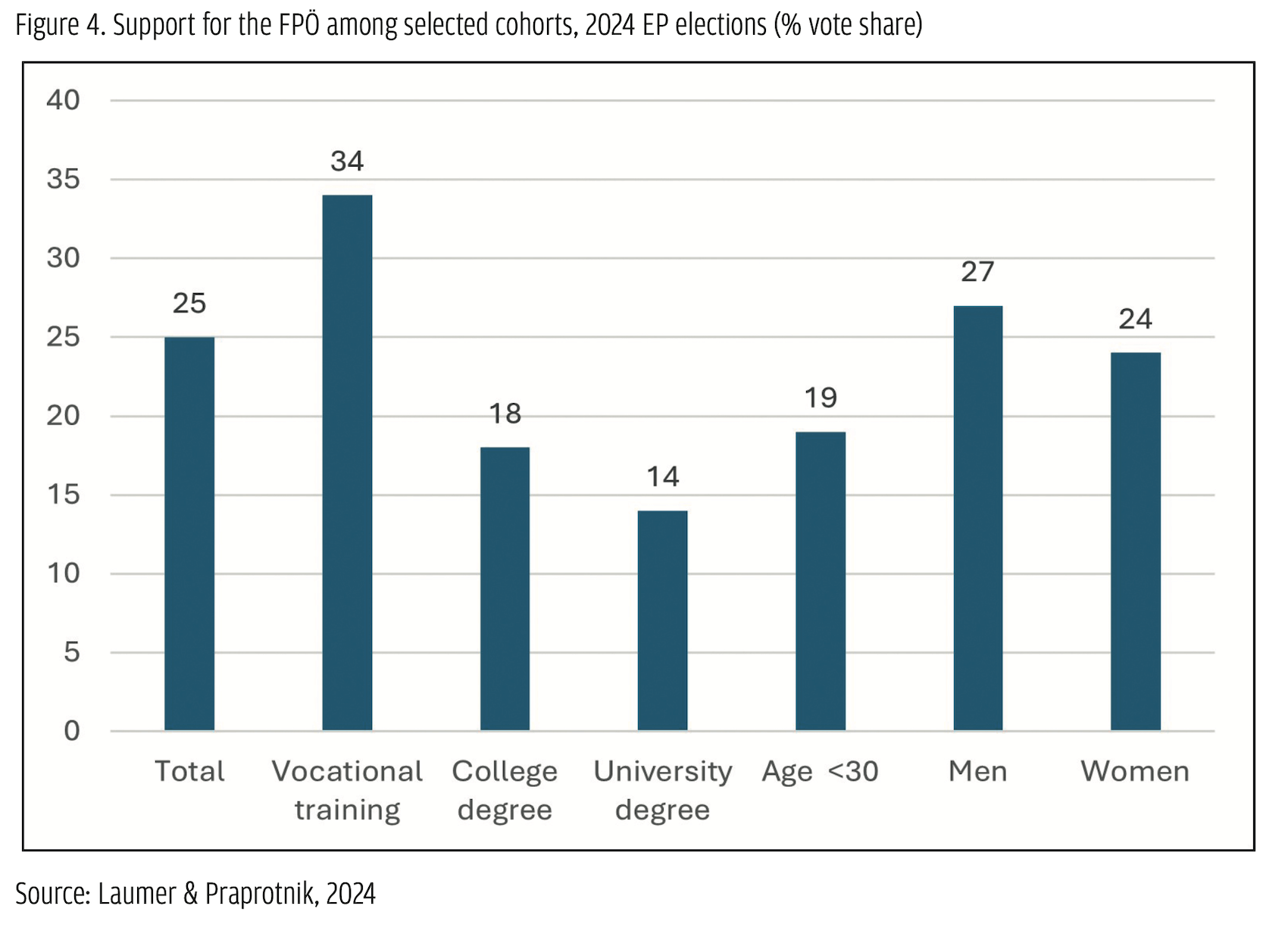

Looking at sociodemographic characteristics (Figure 3), the FPÖ somewhat underperformed amongst voters below the age of 30. Regarding education, it was most successful amongst voters who had completed vocational training and least successful amongst high-school and university graduates. Interestingly, and in line with preceding regional elections (Salzburger Nachrichten, 2024), the once significant gender gap has shrunk considerably compared to the elections in 2019. While back then, 26% of men but only 10% of women voted for the FPÖ, this time it was 27% of men compared to 24% of women. Amongst voters holding at least a college degree, the gap even vanished entirely, with 16% of men and 17% of women opting for the FPÖ (Laumer & Praprotnik, 2024). Amongst others, these changes may be a consequence of the position the party took during the COVID-19 pandemic (especially its critique to discriminate restrictions between vaccinated and non-vaccinated citizens) – which was also found among many (also highly-educated) women (Die Presse, 2021).

Looking at sociodemographic characteristics (Figure 3), the FPÖ somewhat underperformed amongst voters below the age of 30. Regarding education, it was most successful amongst voters who had completed vocational training and least successful amongst high-school and university graduates. Interestingly, and in line with preceding regional elections (Salzburger Nachrichten, 2024), the once significant gender gap has shrunk considerably compared to the elections in 2019. While back then, 26% of men but only 10% of women voted for the FPÖ, this time it was 27% of men compared to 24% of women. Amongst voters holding at least a college degree, the gap even vanished entirely, with 16% of men and 17% of women opting for the FPÖ (Laumer & Praprotnik, 2024). Amongst others, these changes may be a consequence of the position the party took during the COVID-19 pandemic (especially its critique to discriminate restrictions between vaccinated and non-vaccinated citizens) – which was also found among many (also highly-educated) women (Die Presse, 2021).

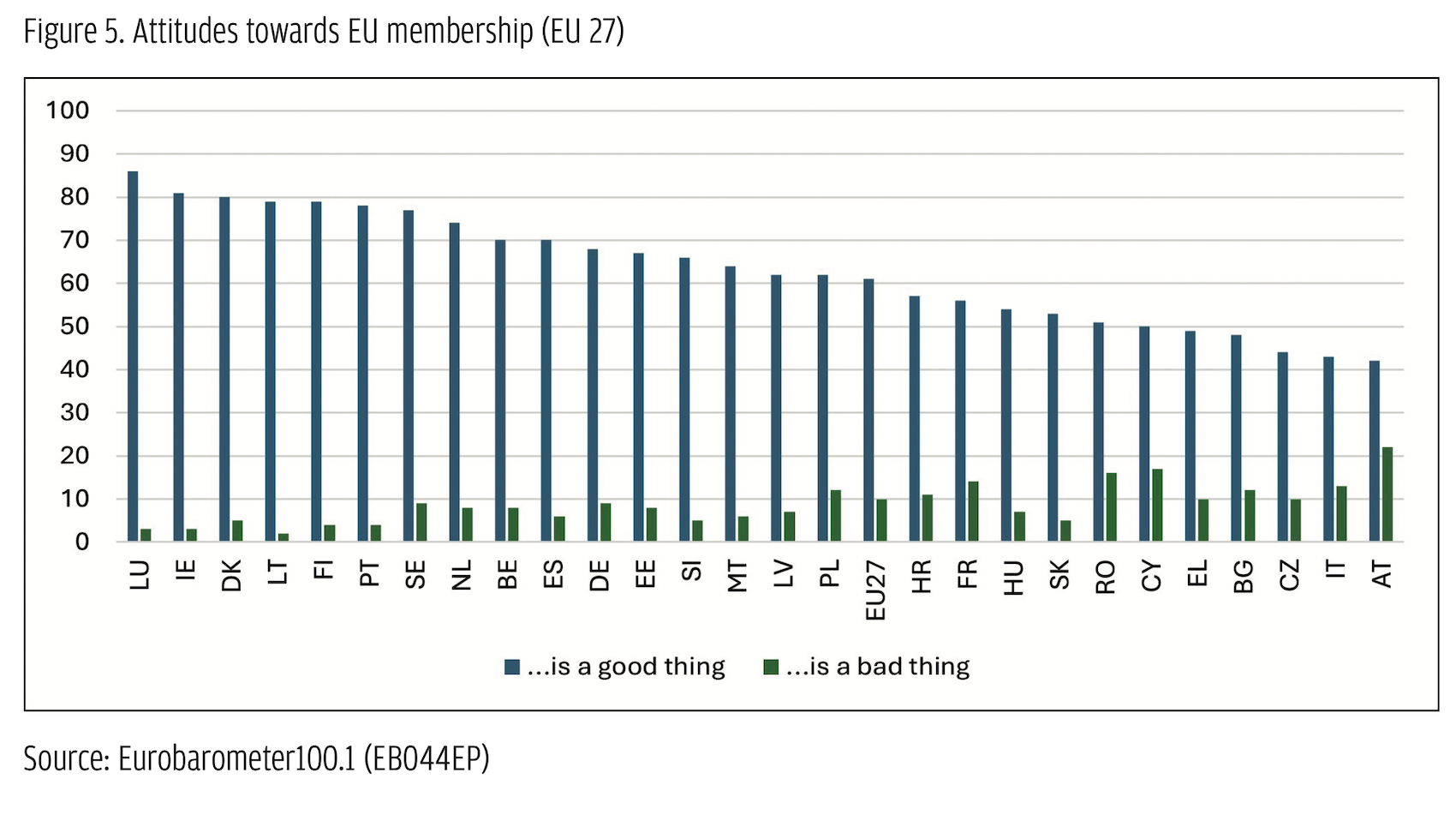

Looking at voters’ issue preferences shows that, generally, there is quite a significant demand for EU-critical positions within the Austrian electorate. While in the 1994 constitutional referendum on the country’s EU accession, a two-thirds majority voted ‘yes’, approval rates started to drop soon thereafter, and Austrian citizens have ranked amongst the most critical ones across the EU ever since (Fallend, 2008). As Figure 5 shows, in the Eurobarometer from autumn 2023 (European Parliament, 2023), Austria not only recorded the highest share of citizens seeing EU membership as a ‘bad thing’ (22%) but also the lowest share of those seeing it as a ‘good thing’ (42%).

Looking at voters’ issue preferences shows that, generally, there is quite a significant demand for EU-critical positions within the Austrian electorate. While in the 1994 constitutional referendum on the country’s EU accession, a two-thirds majority voted ‘yes’, approval rates started to drop soon thereafter, and Austrian citizens have ranked amongst the most critical ones across the EU ever since (Fallend, 2008). As Figure 5 shows, in the Eurobarometer from autumn 2023 (European Parliament, 2023), Austria not only recorded the highest share of citizens seeing EU membership as a ‘bad thing’ (22%) but also the lowest share of those seeing it as a ‘good thing’ (42%).

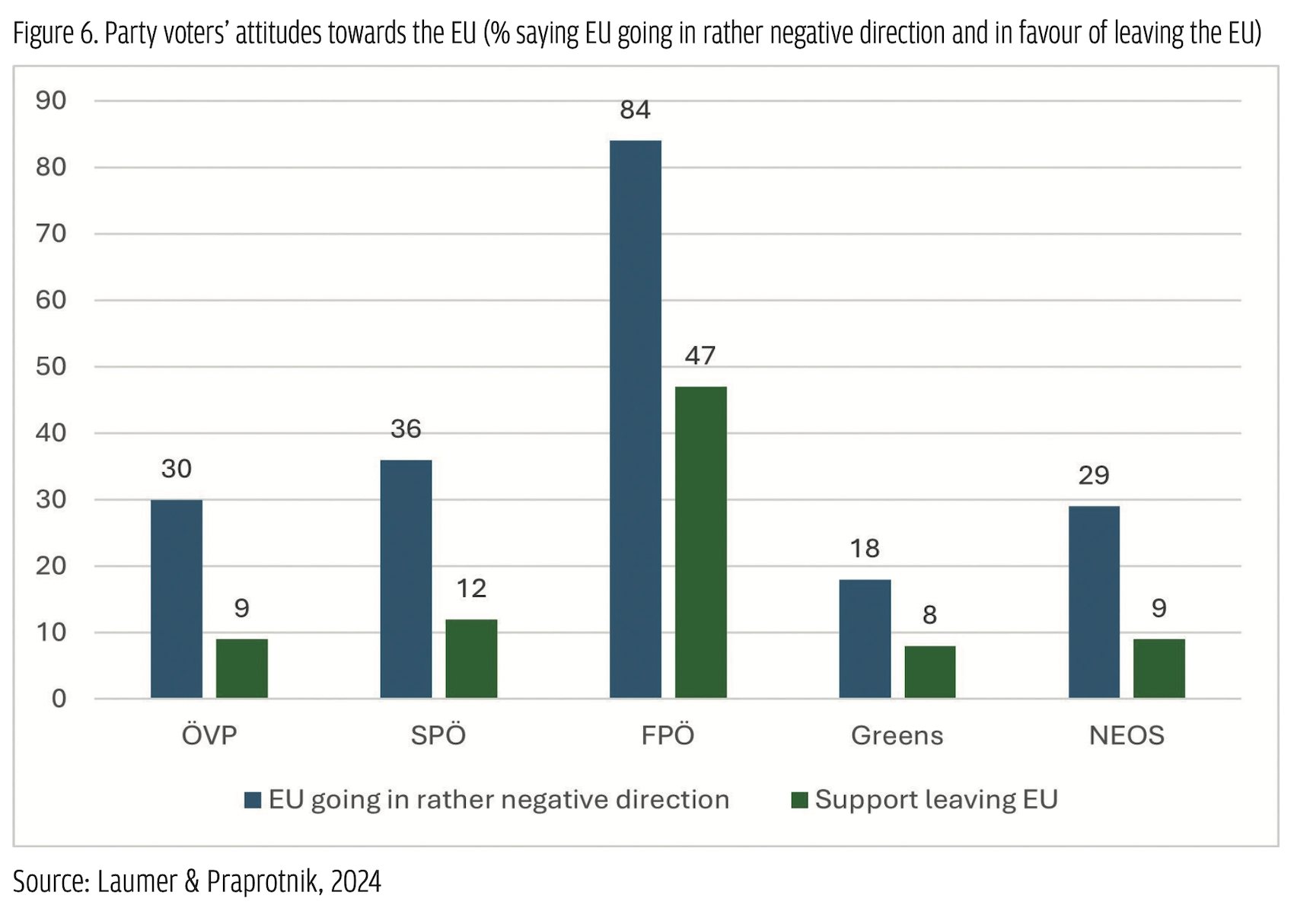

The FPÖ was very successful in attracting these groups. According to exit polls, 84% of its voters see the EU taking a rather negative development and 63% would even support Austria leaving the EU (Figure 6).

The FPÖ was very successful in attracting these groups. According to exit polls, 84% of its voters see the EU taking a rather negative development and 63% would even support Austria leaving the EU (Figure 6).

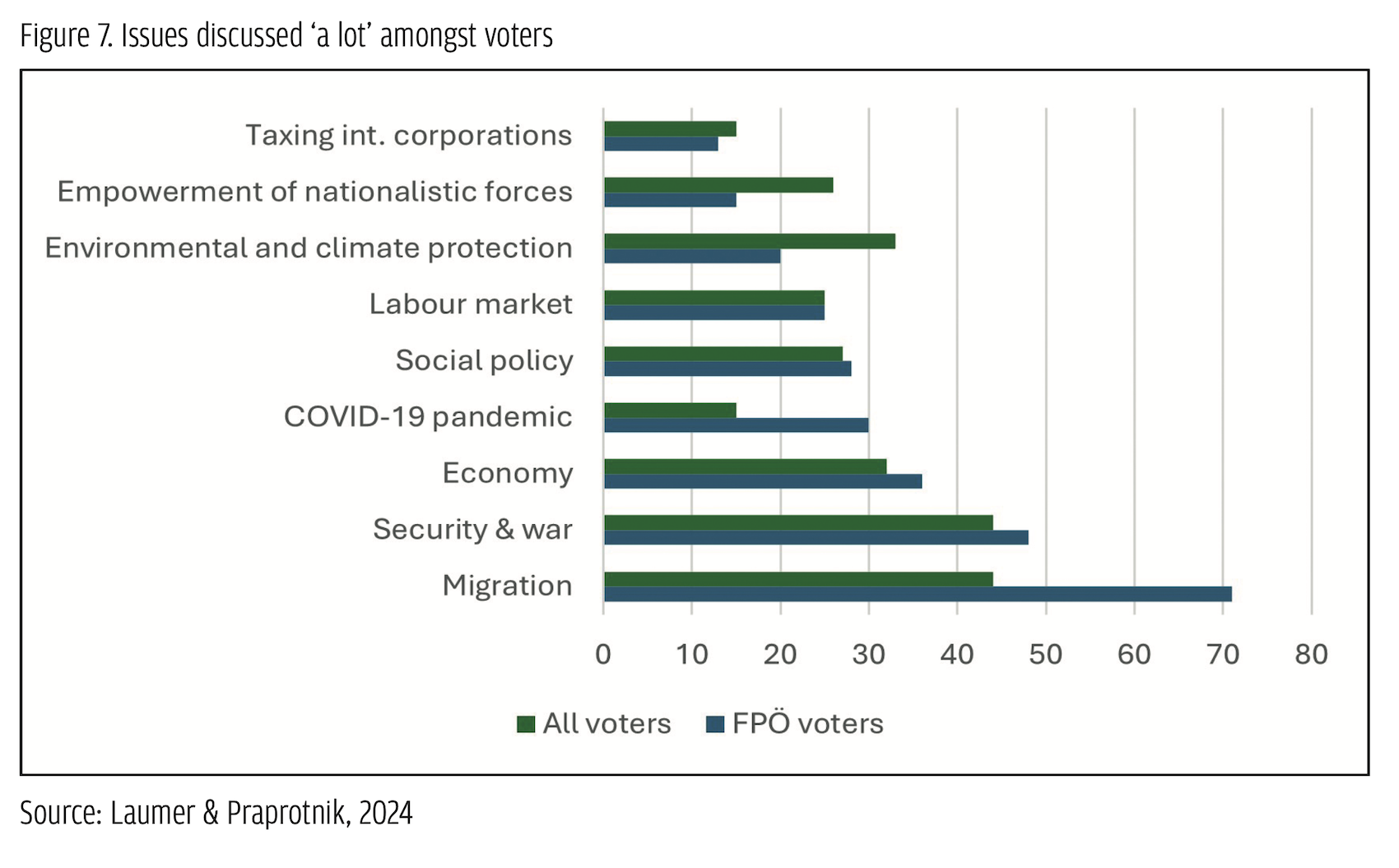

Overall, however, only 4% stated that EU protest was their main reason to vote for the FPÖ, while 40% pointed to the party’s issue positions more generally. Looking at these issues, again, reveals a considerable overlap with the issues the party pushed in its campaign. Among the issues FPÖ voters discussed ‘a lot’ before the elections, ‘migration’ clearly ranks highest (71%), followed by ‘security and war’ (48%), the ‘economy’ (36%), and the ‘Covid pandemic’ (30%), with ‘environment and climate protection’ clearly lagging behind (20%).

Overall, however, only 4% stated that EU protest was their main reason to vote for the FPÖ, while 40% pointed to the party’s issue positions more generally. Looking at these issues, again, reveals a considerable overlap with the issues the party pushed in its campaign. Among the issues FPÖ voters discussed ‘a lot’ before the elections, ‘migration’ clearly ranks highest (71%), followed by ‘security and war’ (48%), the ‘economy’ (36%), and the ‘Covid pandemic’ (30%), with ‘environment and climate protection’ clearly lagging behind (20%).

Public attention for the elections overall was relatively modest. About eight weeks before the elections, less than 50% of the Austrian electorate reported knowing the parties’ lead candidates, and even more stated that they could not assess their work (Die Presse, 2024). To the extent that the election was an issue, however, the FPÖ and its core issues featured quite prominently in the debates. In the three TV debates that featured all lead candidates, migration and the war between Russia and Ukraine were discussed for the longest time (followed by the climate crisis). Given the singularity of its positions, the FPÖ was criticized by all other parties quite harshly in all these debates. This criticism resulted in the FPÖ receiving by far the most attention and also allowed the party to (once again) present itself as the only ‘real’ alternative vis-à-vis a purported Einheitspartei (‘single political party’), composed of the ÖVP, the Social Democrats (SPÖ), the Greens and the Liberals. A similar phenomenon can be observed regarding general news coverage where, for example, the election poster discussed above met with extensive criticism by journalists both nationally and internationally, pushing attention to the FPÖ itself and its political demands even further (Hammerl, 2024).

Public attention for the elections overall was relatively modest. About eight weeks before the elections, less than 50% of the Austrian electorate reported knowing the parties’ lead candidates, and even more stated that they could not assess their work (Die Presse, 2024). To the extent that the election was an issue, however, the FPÖ and its core issues featured quite prominently in the debates. In the three TV debates that featured all lead candidates, migration and the war between Russia and Ukraine were discussed for the longest time (followed by the climate crisis). Given the singularity of its positions, the FPÖ was criticized by all other parties quite harshly in all these debates. This criticism resulted in the FPÖ receiving by far the most attention and also allowed the party to (once again) present itself as the only ‘real’ alternative vis-à-vis a purported Einheitspartei (‘single political party’), composed of the ÖVP, the Social Democrats (SPÖ), the Greens and the Liberals. A similar phenomenon can be observed regarding general news coverage where, for example, the election poster discussed above met with extensive criticism by journalists both nationally and internationally, pushing attention to the FPÖ itself and its political demands even further (Hammerl, 2024).

Discussion and perspective

Summing up, the populist radical-right Freedom Party’s run for the 2024 EP elections relied on well-proven recipes, which the party has been applying highly successfully throughout the last 30 years. In terms of issues, it focused on culturally framed topics like EU critique and calls against migration, which it combined with other issues that have been highly salient amongst the Austrian electorate and on which the party took a position that was taken by no other (established) Austrian party like an alleged ‘neutral’ position in the Ukrainian war (which de facto would result in strengthening the Russian side), and a highly critical position towards EU-measures to combat the climate crisis. Rhetorically, the party strongly relied on a Manichean frame, portraying its national opponents and EU-level actors/institutions as corrupt elites or members of the de facto Einheitspartei. This strategy seemingly paid off, as the FPÖ landed in the first place for the first time in a nationwide election.

Due to this success, there is little reason to expect the FPÖ to significantly change its strategy or the policies it prioritizes in the coming legislative period. Issues like migration, climate change or even the war in Ukraine are unlikely to vanish soon. And given that EU decisions constitutionally rely on broad centrist compromises, it suggests that whatever policies EU institutions manage to agree on, they will always provide ample room for criticism from a populist, radical-right point of view.

Concerning politics, it will be interesting to see how cooperation with other populist parties will proceed and develop in the coming term. Notably, the FPÖ was one of only two parties of the Identity and Democracy (ID) group that voted against the exclusion of the AfD due to statements of the latter’s lead candidate suggesting sympathy for former members of the national-socialist SS just before the elections. After the elections, the FPÖ left ID and, together with Hungary’s Fidesz (which left the European People’s Party in 2021) and the Czech ANO (formerly of Renew Europe), founded Patriots for Europe (PfE), which most of the other former ID members have subsequently joined. However, negotiations with the AfD to join the group failed, leading to the foundation of another new group – Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN).

It remains to be seen how the FPÖ will position itself in possible future disputes between and within these groups like, for example, when it comes to their position concerning the Russia–Ukraine War, where some parties (like the FPÖ) hold close ties with Russia, while others see Russia as a security threat to their own country. Overall, however, it seems that politics at the EU level play a subordinate role for the party at large. Owing also to its nationalist agenda, the party probably does not see the main purpose of EU-level politics as shaping policies in Brussels but rather leveraging them to increase electoral support at home.

(*) Eric Miklin is Associate Professor of Austrian Politics in Comparative European Perspective in the Department of Political Science at the Paris-Lodron University of Salzburg, Austria. His research and publications focus on democracy, party politics and parliamentarism with a special focus on the interplay between the national and the European level. E-mail: eric.miklin@plus.ac.at

References

Bundesministerium für Inneres (2023) Verfassungsschutzbericht 2023.https://www.dsn.gv.at/501/files/VSB/180_2024_VSB_2023_V20240517_BF.pdf

Bartlau, C. (2018, 2 February) Freiheitliche Partei Europas: Wie hätt’ ma’s denn gern? Zeit Online. https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2018-02/freiheitliche-partei-oesterreichs-regierung-opposition-identitaet/komplettansicht

Die Presse (2021, 8 August) Impfung: Frauen sind skeptischer. Die Presse https://www.diepresse.com/6018633/impfung-frauen-sind-skeptischer

Die Presse (2024, 22 April) Nicht einmal die Hälfte der Österreicher kennt die EU-Spitzenkandidaten. Die Presse https://www.diepresse.com/18391193/nicht-einmal-die-haelfte-der-oesterreicher-kennt-die-eu-spitzenkandidaten

Eberl, J. M., Huber, R. A., & Greussing, E. (2021) From populism to the ‘plandemic’: Why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31(sup1), 272–284.

European Parliament (2023) Eurobarometer Data Annex, Parlameter 2023. Directorate General for Communication (Public Opinion Monitoring Unit). file:///C:/Users/miklin/Downloads/EP_Autumn_2023_EB044EP_Results_Annex_en.pdf

Frölich-Steffen, S. (2004). Die Identitätspolitik der FPÖ: Vom Deutschnationalismus zum Österreich-Patriotismus. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 33(3), 281–295.

FPÖ (2017) Österreicher verdienen Fairness. Freiheitliches Wahlprogramm zur Nationalratswahl 2017. (Brochure). https://www.fpoe.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Wahlprogramm_8_9_low.pdf

FPÖ (2024a, 10 July) Party Program of the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ).https://www.fpoe.at/parteiprogramm/parteiprogramm-englisch/

FPÖ (2024b) Vorhang auf für UNSER Österreich. Frei. Sicher. Neutral. [Brochure]. https://www.fpoe.at/fileadmin/user_upload/www.fpoe.at/Websites/EU-Wahl_2024/Wahlprogramm/Wahlprogramm_20x20_Web.pdf

Fallend, F. (2008). Euroscepticism in Austrian political parties: ideologically rooted or strategically motivated? In: P. Taggart, P., & A. Szczerbiak (eds) Opposing Europe? The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism. Vol. I: Case Studies and Country Surveys. Szczerbiak, Oxford University Press, 201–220.

Freiheitlicher Parlamentsklub (2024, 10 May) FPÖ – Vilimsky zu EU-Wahlkampfauftakt: ‚Wir wollen die Nummer eins werden!‘ [Press release], https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20240510_OTS0109/fpoe-vilimsky-zu-eu-wahlkampfauftakt-wir-wollen-die-nummer-eins-werden

Hammerl, M. (2024, 7 June) Wie die Kandidaten im EU-Wahlkampf performt haben. Kurier. https://kurier.at/politik/inland/eu-wahl-kandidaten-analyse-schieder-lopatka-vilimsky-schilling-brandstaetter-performance/402910168

Heinisch, R. (2003) Success in opposition–failure in government: explaining the performance of right-wing populist parties in public office. West European Politics, 26(3), 91–130.

Heinisch, R. & Hauser, K. (2016) The Mainstreaming of the Austrian Freedom Party: The More Things Change…. In: Tjitske Akkerman, Sarah de Lange, Matthijs Rooduijn (eds) Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream? Routledge, 46–62.

Heinisch, R. & Hofmann, D. (2023) The Case of the Austrian Radical Right and Russia During the War in Ukraine. In: Gilles Ivaldi. G & Zankina, E. (eds) The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-wing Populism in Europe. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), 33–46.

Kurier (2024, 12 February) FPÖ: Orban-Vorstoß gegen EU-Direktwahl ‚überlegenswert‘ Kurier. https://kurier.at/politik/inland/fpoe-orban-vorstoss-gegen-eu-direktwahl-ueberlegenswert/402776170

Kurz, H-P (2024, 8 June) Morgen, am 9. Juni geht es um alles. Die #Europawahl2024 ist eine Volksabstimmung über unsere Zukunft. Wir wollen keinen EU-Zentralstaat, sondern unsere #Souveränität zurück. [Post]. X. https://x.com/hpkurz_fpoe/status/1799471451373785220/photo/1

Laumer, D & Praprotnik, K (2024) Europawahl 2024. Wählerstromanalyse und Wahlbefragung. Institut für Strategieanalysen GmbH & FORESIGHT Research Hofinger GmbH. https://www.foresight.at/fileadmin/user_upload/wahlen/2024_FORESIGHT-ISAWahlbefragung_EUW24-Grafiken.pdf

Mudde, C. (2017) Populism. An Ideational Approach. In: Rovira Kaltwasser, C., Taggart, P., Ochoa Respejo, P. & Ostiguy, P. (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Oxford University Press, 27–47

Obermaier, F. & Obermayer, B. (2019) Die Ibiza-Affäre. Innenansichten eines Skandals, Kiepenheuer & Witsch.

Salzburger Nachrichten (2024, 5 March) Gender Gap: Frauen wählen tendenziell links.

Salzburger Nachrichten. https://www.sn.at/politik/innenpolitik/gender-gap-frauen-154507360.

Vilimsky, H. (2023, 17 July) Mit seinen aktuell 705 Abgeordneten ist das Europaparlament schon heute das drittgrößte Parlament der Welt. …. [Post]. X. https://x.com/vilimsky/status/1680822701370294272

Vilimsky, H. (2024a, 24 May) Ein belgisches Gericht hat jetzt die Ermittlungen zu ‚Pfizergate‘, der umstrittenen EU-Impfstoffbeschaffung, auf Dezember verschoben … [Post]. X. https://x.com/vilimsky/status/1794002389063938116

Vilimsky, H. (2024b, 9 June) Liebe Freunde, warum es SO WICHTIG ist, am Sonntag die FPÖ zu wählen… [Post]. X. https://x.com/vilimsky/status/1799639530573647977

Wodak, R. (2005). Populist discourses: the Austrian case. In: Rydgren, J. (ed.) Movements of exclusion: Radical right-wing populism in the Western world. Nova Publishers, 121–145.