In a compelling interview with the ECPS, renowned historian Professor Michael Kazin explores the rise of right-wing populism as a “morbid symptom” of today’s political transition. Drawing on Antonio Gramsci’s theory of interregnum, Kazin analyzes Donald Trump’s presidency, highlighting its profound impact on American and global politics. From galvanizing his MAGA base by aligning economic grievances with cultural conservatism to forging ties with far-right leaders abroad, Trump’s leadership reflects the challenges of this transitional era. Kazin also envisions the potential for a progressive populism rooted in economic justice to counterbalance these dynamics.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

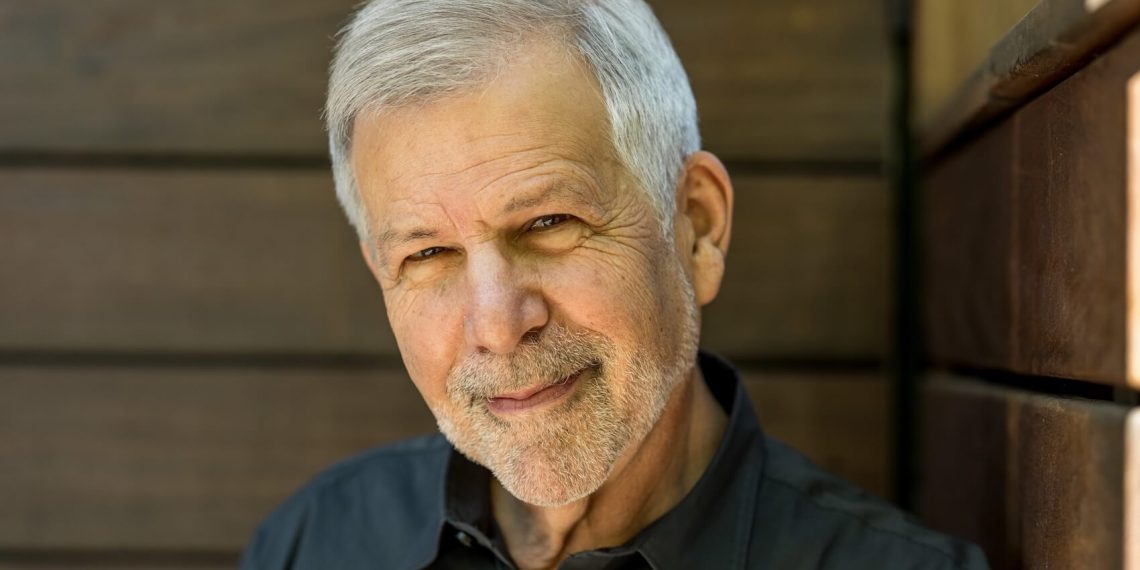

Renowned historian and scholar of American politics and social movements, Professor Michael Kazin of Georgetown University, offers a thought-provoking analysis of right-wing populism in the context of Donald Trump’s presidency in a comprehensive interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). Framing contemporary politics as an "interregnum"—a period of transition—Professor Kazin draws on Antonio Gramsci’s observation that such times often produce "morbid symptoms," which he associates with the global rise of right-wing populism. He explores how Trump’s leadership embodies this phenomenon, highlighting its implications for both domestic and international politics.

In the interview, Professor Kazin delves into Trump’s unique ability to sustain a populist movement despite his focus on personal popularity over policy. He discusses how Trump has galvanized his base by aligning economic grievances with cultural conservatism, creating a potent political force that continues to shape American political discourse. Professor Kazin critiques Trump’s approach to governance, describing his first administration as “wretched,” marked by policy ignorance and self-serving actions. However, he acknowledges that Trump’s movement, particularly the MAGA base, has no parallel within the Democratic Party, providing him with a solid foundation of unwavering support.

Professor Kazin also examines the potential global ripple effects of Trump’s second term, noting his alignment with leaders like Viktor Orbán and the admiration he garners from right-wing populist movements in Europe. While Trump’s “America First” stance complicates the formation of international alliances, Professor Kazin suggests that his presidency could embolden far-right leaders worldwide. However, he tempers this with cautious optimism, emphasizing the resilience of American democratic institutions and the structural limits of Trump’s power.

Finally, Professor Kazin explores the broader dynamics of populism, contrasting left- and right-wing variants. He argues that left-wing populism, rooted in economic justice and social democracy, offers a constructive path forward. As global demands for equitable governance grow, Professor Kazin envisions the potential for a revival of progressive populism that challenges elite power while addressing urgent issues like economic inequality and climate change.

The interview with Professor Kazin offers a nuanced perspective on Trump’s presidency, the resilience of democratic institutions, and the evolving role of populism in shaping both domestic and global politics.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Michael Kazin with some edits.

Populism in America: Bridging or Deepening Divides?

Professor Kazin, thank you so much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question. In your book titled The Populist Persuasion, you discuss how populist rhetoric has evolved in the U.S. What role does populism play in bridging or deepening the divide between cultural and economic grievances today?

Professor Michael Kazin: As you know, populism is both a language and, some would argue, a governing philosophy. I focus on it as a language in American history, with ramifications for populism in other countries, of course. Historically, I think there has been a distinction in the United States—which is really all I can speak about with authority—between left-wing populism and right-wing populism.

Left-wing populism tends to focus on an economic elite—the 1% versus the 99%, the robber barons, the plutocrats, the monopolists. Many terms have been used to critique those with significant wealth and economic power. Left-wing populists aim to unite a large majority, regardless of gender, race, or national origin.

In contrast, right-wing populists in the US—and to some degree in Europe—view “the people” as a broad middle segment of the population, primarily native-born individuals. According to right-wing populists, this group is being exploited and oppressed by two forces: a small elite at the top (both economic and cultural, and sometimes perceived as controlling the state, such as the European Union in Europe or the federal government in the US) and a small but growing group at the bottom, often composed of non-white and immigrant populations.

Historically, this group at the bottom has included Latinos, Asian Americans, and African Americans. More recently, undocumented or illegal immigrants have been the focus. Right-wing populists argue that these groups are used by the elite to drive down wages and erode the cherished culture of the native-born middle class.

Generally, this is how left-wing and right-wing populists operate in the US, with similar analogs in Europe.

Currently, in American politics, left-wing populists—such as Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and other progressives within and outside the Democratic Party—are striving to emphasize the tradition of left-wing populism. However, they face challenges because Democrats and progressives also prioritize cultural issues, such as more lenient immigration policies, transgender rights, and racial equality. This creates some tension with economic left-wing populists, who prefer to focus narrowly on issues like corporate greed, wealth inequality, and combating the power of the very rich, including figures like Donald Trump.

On the right, as most people are aware, Donald Trump exemplifies the continuity of right-wing populism from the 19th century to today. Right-wing populists argue that a “Hollywood elite” or “woke elite” in universities and cultural institutions seeks to impose its values on the hardworking, native-born majority. Additionally, they claim that undocumented immigrants take jobs from native-born Americans, drive down wages, and increase crime in cities.

This is how the two traditions of left-wing and right-wing populism are playing out in contemporary American politics.

Populist Rhetoric and Its Impact on Economic Inequality and Social Justice

How has populist rhetoric shaped the policy priorities of modern political parties in the US, particularly regarding economic inequality and social justice?

Professor Michael Kazin: Social justice is a term that’s hard to define. It’s been used by both the left and the right throughout American history, so I’ll set that aside for the moment. In terms of economic inequality, this has been a longstanding issue in American politics, but it has especially risen to prominence as a major concern for both right-wing and left-wing populists since the Great Recession of 2008–2009. Following the well-publicized but relatively small Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011–2012, progressive Democrats have increasingly focused on this issue. They argue that neoliberalism—which many view as the dominant ideology in American politics and economics since the 1970s, especially after Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980—has exacerbated economic inequality.

Progressive Democrats have supported programs like those championed by Joe Biden, albeit with moderate success, to help unions organize, provide childcare benefits to all American families, and implement other measures aimed at narrowing economic inequality.

On the other hand, conservative populists, including figures like Donald Trump and J.D. Vance, argue that the primary issue with economic inequality lies with corporations that they claim are “too woke” and favor individuals with the “right” cultural politics over ordinary Americans. Some very conservative Republicans have embraced a form of anti-corporate politics.

For example, Josh Hawley, a Senator from Missouri, has supported the Teamsters Union, one of the largest unions in America. Additionally, some right-wing Catholic thinkers have drawn on the Catholic Church’s social justice tradition, referencing papal encyclicals like Rerum Novarum (1891) and others to argue that unions are essential for improving the lives of ordinary people and to criticize practices like excessive rents and interest rates that harm workers and the poor.

This trend has given rise to a form of “Catholic populism,” which uses these religious principles to legitimize arguments against corporate power. An interesting book on this topic, Tyranny, Inc., by a conservative journalist, critiques corporations for engaging in behavior that harms workers, such as union-busting, charging excessive credit card interest, and denying healthcare coverage.

There is, to some extent, agreement between right-wing and left-wing populists in the US on reducing corporate power and supporting private-sector unions. Currently, only 6% of private-sector workers in the US are unionized—a historically low figure.

However, significant disagreements remain between right-wing and left-wing populists, particularly on cultural issues, which are deeply entrenched and difficult to reconcile. For example, debates over abortion—whether it is a fundamental right for women or equivalent to the killing of babies—highlight how cultural arguments are often intractable and resistant to compromise.

In one of your interviews, you argue that ‘if the political and economic elites in our society and others around the world were more effective at living up to their ideals, populist talkers would likely be less popular.’ What do you mean by ‘ideals of political and economic elites?’

Professor Michael Kazin: Perhaps I should have said the ideals of the nation led by these elites to be more accurate. In the United States, especially—and to varying degrees in Europe—the stated ideals include equality, democracy, majority rule, and a government that promotes the common welfare, as referenced in the preamble to the American Constitution. These ideals are echoed in other historical documents, such as the Declaration of the Rights of Man in Europe.

As a social democrat, I would say that if social democracy were practiced more widely and people were guaranteed a decent life in their societies, populism would likely be less popular. For example, in the United States between the late 1940s and the mid-1960s, despite many challenges, it was generally a prosperous time. Unions were very powerful, Social Security was extended to nearly every working American, and the beginnings of health insurance coverage for older and poorer individuals under Medicare and Medicaid were implemented. During that period, populist rhetoric was not particularly influential, and populist movements were relatively subdued. While there were significant social movements, such as the Black freedom movement, they were primarily advocating for the inclusion of an oppressed minority in American life rather than claiming to represent the great majority. Of course, there were radical elements within some movements, but they were not the mainstream.

In my recent book, What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party, I argue that "moral capitalism"—a phrase I borrow from a fellow historian—was the governing promise of the Democratic Party during these years. Democrats were the majority party, and most Americans, including working-class citizens, believed that things were improving. When people believe their lives are getting better, populist leaders and movements struggle to gain traction.

Trump’s Leadership Defined by Self-Interest and Controversy

In one of your articles, you characterize Donald Trump’s first administration as ‘one of the most wretched president and administration in living memory.” What factors have contributed to your defining of Trump’s administration as the most wretched?

Professor Michael Kazin: Well, of course, "wretched" is a loaded, emotional term, and here I’m speaking from my own preferences. There’s no scholarly objectivity possible in this context. I could also talk about why he won again last November, but first, let me focus on the question.

As a leader, I think Trump is someone primarily interested in his own popularity and not particularly interested in policy. He wants to be the center of attention at all times and is committed to no ideal or policy unless it benefits him personally. He’s also unwilling to take risks, particularly when it comes to policy decisions, which I believe was evident during his first term and will likely remain true during his second term—though, of course, we’ll have to wait and see.

His personal behavior also contributes to this characterization. He has been credibly accused of actions that would be considered rape in many nations, though he wasn’t convicted of rape but rather of defaming someone who accused him. His statements about immigrants and what he referred to as “shithole countries,” among other things, reflect his character. As an individual, I find him to be a rather wretched person—someone I wouldn’t want to associate with or have anyone I know associate with.

That said, his administration itself was more cautious than I expected, in part because he leads a party that still includes more traditional, cautious members. Many corporate executives and traditional Republicans influenced his policies. For instance, his Cabinet included several conventional Republican figures, and the Speaker of the House for much of his term was Paul Ryan, a Reaganite libertarian Republican focused on cutting the size of government rather than pursuing anti-immigrant crusades.

The major accomplishment of his administration aligned with a long-standing conservative Republican agenda: cutting taxes, especially for wealthier Americans, though all Americans received some form of tax cut. This is something Ronald Reagan might also have done.

In that sense, while his administration had the potential to be wretched, it was less so than I expected. However, Trump’s statements and actions on immigration were deeply problematic. His attempt to build a wall across the southern border wasted significant funds and was ultimately easy to evade. This demonstrated not only ignorance about policy but also a lack of genuine concern for it.

Unlike other American presidents, as the leader of the most powerful state in the world, Trump showed very little interest in the actual workings of the state unless they directly benefited him personally. In that sense, I would still describe him as a wretched leader.

You argue that ‘like most adherents of left egalitarian politics, I believe the only path to such a future (the more egalitarian and climate-friendly society) lies in adopting a populist program about jobs, income, health care, and other material necessities, while making a transition to a sustainable economy? What exactly do you mean by ‘populist programs?’

Professor Michael Kazin: Well, by that, I mean majoritarian—programs that genuinely benefit the majority of people. When governments are popular, that’s typically what they do. So, in this sense, being “popular” and being “populist” can overlap, though they are not always synonymous.

As I mentioned before, I believe an honest social democracy, or what I would call “moral capitalism” in the US, is the best approach. Such programs would include housing allowances, universal health care that is well-administered and provides good working conditions for healthcare workers, unions to protect the majority of people against workplace abuse, and, critically, a vigorous transition to a sustainable economy—because without that, the entire world is in trouble.

Now, using the term “populist” might seem to betray my own definition of populism, which in American history refers primarily to a discourse or rhetoric. But I don’t subscribe to the simplistic view of “populism bad, liberalism good.” As I argue in my book, The Populist Persuasion, populism can be a way for ordinary people—and movements aiming to represent them—to highlight the gap between a society’s stated ideals and the actual performance of its elites, whether cultural, political, or economic.

Populism can play a very positive role by pointing out these shortcomings and harking back to a society’s ideals, including those rooted in religion, like charity and comfort for the afflicted. It doesn’t necessarily demand, as socialism often does, a completely different kind of society—although socialists can also adopt populist rhetoric. Instead, it appeals to the ideals of the existing society, challenging elites to live up to them.

This is why I think populism has an important role in producing a decent society. Unlike some critics, like Jan-Werner Müller, who argue that populism always fuels movements that lead to authoritarian leaders, I believe populism doesn’t have to serve that role. While it certainly has done so in some parts of Europe, where we see leaders with authoritarian tendencies in and out of office, I think left-wing populism can play a vital and constructive role.

Trump’s Second Term: The Future of Populist Politics in the US and Beyond

How do you explain Donald Trump’s victory for a second term, given his open and aggressive endorsement of populist policies both in the US and globally? Additionally, how might his administration reshape the populist narrative domestically, particularly in aligning economic grievances with cultural conservatism?

Professor Michael Kazin: That’s an important question, obviously, and one we won’t really be able to answer until he’s been several years into his term. Let me address the first part of your question.

Again, you’ve probably read, and your viewers have likely heard and read, many analyses of why Trump won. The most important reason he won—and this is usually why anyone unseats an incumbent party in this country, and probably in others as well—is that most Americans believed the performance of the Biden administration, or the Biden-Harris administration, wasn’t good. This perception was based on several factors, including inflation, a more open immigration policy than most Americans preferred, and, I think, Biden himself, who is a very poor communicator.

Biden used to be a mediocre communicator when he was younger, but in the last couple of years, he became very bad at selling his own programs. Some of those programs, I believe, could have been quite popular if Americans had known more about them, but they didn’t.

This was an election that was actually rather close. For instance, if 232,000 voters in three key states—Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania—had voted differently, with slightly more in Pennsylvania than the other two states, Harris would have been elected, even though she would have won fewer popular votes than Trump. As everyone watching this knows, we don’t have a national popular vote in this country. We have state-by-state elections that determine the presidency.

Trump, on the other hand, is a charismatic figure. While he doesn’t have the majority of Americans on his side, a significant portion—perhaps 30%—strongly supports him. He has a movement, the MAGA movement, which the Democrats don’t have anything comparable to. Even though the Democrats had more people on the ground to get voters to the polls, Trump had more solid support.

As a result, he won somewhat more votes than he did in 2016—about 2 million more popular votes. However, Harris won 10 or 11 million fewer votes than Biden had in 2020. Trump’s victory was largely due to many Democrats deciding not to vote. They were disenchanted enough with the Biden-Harris administration’s performance but not sufficiently motivated by Trump to come out and vote against him.

Now, regarding what Trump will do in terms of reshaping the populist narrative—let me remind myself of the second part of your question here…

How much his administration reshapes the populist narrative domestically.

Professor Michael Kazin: Well, again, it depends on how well he performs, right? This is a question of contingency—how he navigates his role as president during the second term. Trump is a much better politician than he is a policymaker, so he will certainly try to maintain support from both the more traditional Republicans and the cultural populists within his coalition.

On the traditional side, he will aim to keep corporate Republicans on board—those who favor lower taxes, less regulation, and smaller government in general. Simultaneously, he’ll also work to retain the cultural populists who want to drastically cut immigration, both legal and illegal, and who oppose transgender rights and certain aspects of gay and lesbian rights.

Trump will likely attempt to strengthen US manufacturing, pushing for more products to be made domestically. However, this will be challenging given that final manufacturing in the US relies heavily on parts sourced from around the globe. Reducing this dependency and producing those parts domestically, which are currently made more cheaply elsewhere, will be difficult. Nevertheless, he will likely focus on this rhetorically.

As always, much will depend on the state of the economy, the presence or absence of scandals within his administration, and the outcome of the midterm elections. In 2026, Democrats are well-positioned to potentially take back the House of Representatives. If that happens, anything Trump aims to achieve would have to be done through executive actions. While some of these actions may be popular, others might not resonate as well with the public.

Additionally, the 2028 presidential campaign will overshadow the final years of Trump’s term. In fact, the campaign will likely begin even before the 2026 midterm results are fully processed. This means Trump might have only two effective years to accomplish his goals, including efforts to satisfy both the traditional and cultural populists in his coalition.

Trump’s Return: Shaking but Not Breaking American Democracy

How concerned are you about the second Trump administration in terms of the resilience of American democratic institutions? There are those pundits who argue that American democracy will not survive another Trump term.

Professor Michael Kazin: Here I part ways with some others on the left. I don’t think that American democratic institutions are in serious trouble. I believe they will be shaken—and are already being shaken—by Trump’s reelection and his return to power next month.

First of all, Congress is still fairly evenly divided between the two parties, even though Republicans are in charge. Many large states, such as New York, California, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Illinois, are governed by Democrats, and most of these states have Democratic majorities in their legislatures as well. These state governments can act and bring cases to court to challenge some of Trump’s policies.

Civil society in the United States remains relatively strong. There are significant non-governmental organizations, like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which will likely file lawsuits against some of Trump’s actions—particularly those related to immigration. For example, if he tries to deport children born in the US to immigrant parents (who are American citizens by birthright), the ACLU and others will step in.

Even though the grassroots left is somewhat dormant and exhausted since the election, there are still key groups on the left, including unions like the American Federation of Teachers and the United Auto Workers. These organizations were supportive of Kamala Harris and will mobilize opposition against Trump’s administration.

As always, Trump’s ability to act depends on how popular he remains. If his popularity holds, he will have more freedom to pursue his agenda. However, the court system remains a check on his power. While the Supreme Court leans conservative, with three justices appointed by Trump during his first term, other courts are more balanced, with progressives or liberal judges presiding over lower courts.

I anticipate chaos and turmoil, but that doesn’t necessarily mean democratic institutions are in existential danger.

One area of concern is Trump’s apparent eagerness to sue media organizations he disagrees with. For instance, he already sued ABC News over a comment made by anchor George Stephanopoulos, and ABC settled for several million dollars. He might pursue similar legal actions against other media outlets, particularly legacy institutions like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and major networks. While this could intimidate some of these institutions, he won’t be able to silence the Internet or prevent people from organizing protests.

The military, which served as a check on him during his first term—particularly during the protests of 2020—will likely play a similar role this time. He won’t be able to call on the military to suppress peaceful demonstrations, even if he expresses the desire to do so.

I wouldn’t call myself optimistic, but I am hopeful. Also, as I mentioned earlier, he only has four years in this term and likely only two effective years to implement policies. So, I’m not as fearful as some others I know.

Implications for Global Populism and Far-Right Alliances

And lastly, Professor Kazin, right-wing populism continues to rise across Europe despite the liberal European Union’s success story. How do you think populist parties and movements will be influenced globally after Trump begins his second term? Could his presidency embolden far-right leaders abroad and foster new alliances among far-right populist governments?

Professor Michael Kazin: Well, that’s certainly a possibility. As you know, he’s been very close to Viktor Orbán. Orbán has been invited to National Conservative Conferences, and there was even one held in Budapest, which I believe was the first time an American conservative organization hosted its conference overseas. Clearly, right-wing populist leaders, including those of parties like the Rassemblement National (RN) in France, are likely very pleased with Trump’s reelection. This is probably true for right-wing populist parties and movements across the continent.

At the same time, if you emphasize “America First” and express suspicion toward European institutions such as the EU or NATO, it becomes very difficult to form any kind of operationally powerful alliance between Trump and his counterparts in Europe.

Structurally and historically, I believe we’re in what could be described as an interregnum—a period of transition. My friend Gary Gerstle, in his excellent recent book, describes the end of the neoliberal order, which has concluded in many ways and in some places entirely. As the Italian Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci famously said, during such an interregnum, "many morbid symptoms appear." From my perspective, right-wing populism is one such morbid symptom.

However, as demands grow for the state to provide a decent living for a majority of its citizens—and as governments actually fulfill those demands—I think there could be a revival of left-wing populism or social democracy, even if it’s not labeled as such. People will demand that the government deliver on its promises to improve living standards for the majority, ideally in collaboration with private capital.

I am somewhat heartened by the fact that Trump is limited to four years. He cannot serve more than that without a constitutional amendment, which is extraordinarily difficult to achieve in this country—far more so than in many others.

Additionally, most Americans who support Trump are not particularly enthusiastic about alliances between the United States and other countries. They prefer the US to remain independent of such alliances, especially if those alliances are perceived to be costly. So, we’ll have to see how this unfolds.