In this wide-ranging interview with the ECPS, Dr. Matías Bianchi offers a powerful diagnosis of contemporary illiberalism. Moving beyond regime-centric explanations, Dr. Bianchi argues that today’s defining shift is normative: “illiberal actors no longer need to pretend they are liberal.” He shows how illiberalism now operates through transnational networks embedded within liberal democracies, sustained by funding, coordination, and discourse originating largely in the Global North. Highlighting the erosion of liberal legitimacy, the normalization of illiberal language, and the structural weakening of the nation-state, Dr. Bianchi underscores why democratic institutions struggle to respond—and what is at stake if they fail to adapt.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In an era marked by democratic backsliding, geopolitical fragmentation, and the global diffusion of illiberal norms, understanding the evolving nature of authoritarian and illiberal politics has become an urgent scholarly and policy task. In this in-depth interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Dr. Matías Bianchi, Director of Asuntos del Sur in Buenos Aires and co-author of “The Illiberal International,” offers a compelling diagnosis of contemporary illiberalism—one that departs decisively from regime-centric and state-centric explanations.

At the heart of Dr. Bianchi’s analysis lies a striking observation captured in the interview’s headline: “Illiberal actors no longer need to pretend they are liberal.” For Dr. Bianchi, the defining feature of the current moment is not the novelty of illiberal ideas themselves, but rather a profound normative and cultural shift that has lifted the constraints once requiring authoritarian or illiberal actors to cloak their agendas in liberal rhetoric. As he explains, “What we aim to show is that there is a set of actors working together and collaborating at different levels—geopolitical, institutional, and interpersonal—for whom liberal practices and ideas are no longer the goal.”

This “shedding of pretense,” as Dr. Bianchi describes it, represents a critical marker of the contemporary illiberal turn. Practices that were once “forbidden, punished, or had to be concealed are now openly articulated.” The symbolic need to maintain democratic façades—what Dr. Bianchi recalls through Fidel Castro’s claim that “we are a real democracy”—has eroded. “That veil is no longer necessary,” he argues, signaling a transformation not only in political behavior but also in the boundaries of legitimacy and civility within democratic publics.

Crucially, Dr. Bianchi situates illiberalism not as a discrete regime type but as a networked, relational political formation that increasingly operates within liberal democracies themselves. He emphasizes that many illiberal actors are embedded in ostensibly democratic systems—“in the European Union, the United States, or other contexts”—and that a major novelty of the past decade is that “much of the financing, support, and networking now originates from the US and Europe,” regions once seen as the pillars of the liberal international order.

Throughout the interview, Dr. Bianchi traces how cross-border coordination, transnational funding, and shared discursive strategies—exemplified by platforms such as The Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) or slogans like “Make Europe Great Again”—have accelerated the normalization of illiberalism. These networks thrive amid what he identifies as a deeper crisis of liberalism itself: declining legitimacy, shrinking human rights cooperation, and the inability of liberal institutions to deliver material security, social inclusion, and credible governance in an increasingly unequal and digitally mediated global order.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Dr. Matías Bianchi, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

Illiberal Actors Now Operate Openly Within Liberal Regimes

Dr. Matías Bianchi, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: How do you conceptualize illiberalism in distinction from classical authoritarianism and competitive autocracy? In “The Illiberal International,” illiberalism appears neither reducible to established authoritarian rule nor fully captured by frameworks of competitive authoritarianism or democratic erosion. What core institutional and normative markers define this “illiberal international,” particularly in terms of its relationship to legality, electoralism, and claims to popular sovereignty?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: In our article, we do not engage in a fine-tuned conceptualization of each of the concepts you mentioned. Rather, what we aim to show is that there is a set of actors working together and collaborating at different levels—geopolitical, institutional, and interpersonal—for whom liberal practices and ideas are no longer the goal. Our liberal order, already weakened, is being challenged, and we are not entirely certain about the motivations behind this challenge. Some actors may be seeking greater financial resources, others may wish to control their political space, while others pursue more ideological objectives, such as creating a new order, as in the case of Javier Milei in Argentina. They may have different aims, but what they share is that liberal practices—such as the Woodrow Wilson–style liberal global order—are no longer central.

Traditionally, autocratic or authoritarian frameworks focus primarily on regimes. What we show, however, is that many of these illiberal actors are often operating within liberal regimes—such as those in the European Union, the United States, or other contexts. That is precisely what we seek to demonstrate. A key feature of the current situation is that much of the financing, support, and networking now originates from the US and Europe, which were once the primary sustainers of the liberal global order. This represents a major novelty of the past decade.

As for the practices or markers we observe, one of the most significant is a cultural shift that enables ideas and practices that existed before but are now expressed more openly. In a sense, there has been a shedding of pretense surrounding liberal ideas, allowing actors to operate more freely. This is an important marker. Practices that were once forbidden, punished, or had to be concealed are now openly articulated. Even in Cuba, Fidel Castro used to say, “We are a real democracy.” There was always a veil that needed to be maintained. I believe that this veil is no longer necessary, and that in itself is a telling marker.

Illiberalism Has Gone Transnational

What explains the shift from predominantly domestic processes of democratic backsliding to increasingly coordinated, cross-border illiberal networks? In your article, illiberalism appears less as a discrete regime type than as a relational, networked political formation. How does this reconceptualization challenge state-centric and regime-centric approaches in comparative politics and international relations?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: Many of the things I am going to say are not directly related to the article and are more my own ideas, and not necessarily shared with my co-authors. What we are witnessing is a contested situation. The world order we are living in still includes a liberal order, but it is lacking both legitimacy and power. At the same time, other actors are gaining momentum; they have more financial resources and greater cooperation across many areas, including technology and the military.

This operates at different levels, which is a crucial point. The key dimension here is the network—that these actors are collaborating more than ever before. If you look back a decade or two, these networks were far more limited. The Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), for instance, was something quite restricted. “Make Europe Great Again” was either very limited or did not exist at all. Now, however, these spaces are becoming global. You have CPAC in Latin America, CPAC in Europe, and these platforms are expanding and increasingly sharing resources.

I think this development is related to the loss of pretense—that these ideas no longer need to be hidden. This, in turn, changes the game. There is more funding, while at the same time the liberal camp is lacking resources, lacking investment, and experiencing less cooperation. So, while this dynamic operates at different levels, the networks functioning simultaneously are particularly important.

For example, Tucker Carlson making Milei a global phenomenon, with hundreds of millions of viewers for his interviews, allows people across the United States to become familiar with this phenomenon. All of this network-based collaboration, to me, is absolutely crucial.

Illiberal Power Reveals Itself Through Discourse Before It Acts

Drawing on V-Dem data, the Authoritarian Collaboration Index, and your own empirical research, which indicators most effectively capture the qualitative transformation—not merely the quantitative expansion—of authoritarian cooperation in recent years? Which measures best reveal the growing organizational capacity, coordination, and strategic coherence of illiberal actors at the global level?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: Again, this goes beyond our analysis. I would say, once more, that the key element is the normative shift. There has been a change in what can be said at the level of language. Insults and the demonization of adversaries or other political actors have become more acceptable; at the level of discourse, the line of civility has shifted. This normative change is crucial, and it is followed by action. Language comes first.

When you start making statements such as “women are this,” or when Muslims or immigrants are targeted, you begin naming things, and then actions follow—ICE raids and other measures come afterward. So, the normative shift, in terms of what is allowed without penalties, is essential. In the past, if actions like those taken by Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil or by others had occurred, there would have been phone calls from the White House or Brussels. There would have been at least threats involving investments, financial support, or other consequences.

I am not sure those calls exist anymore. All of these shifts occur, again, at the level of language, which has penetrated civic discourse within societies, but also at the global level, where the normative environment itself has changed. There is a fundamental normative shift at work.

When No One Enforces the Rules, Illiberal Networks Move Faster

Why have authoritarian and illiberal networks become more agile and effective than democratic alliances, despite the latter’s historical institutional advantages? To what extent do procedural neutrality, consensus-based decision-making, and legal formalism within liberal institutions create structural vulnerabilities that illiberal actors exploit?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: That is a very good question. I see liberal practices as a kind of social contract and a global contract. However, they need to be sustained by power. At some point, someone imposed those rules and others complied. I am not sure there is still sufficient power sustaining that liberal order at the international level, or in many cases at the national level. As a result, there is little punishment for violating it. So I am not sure this is primarily a question of institutional design; rather, it is a question of legitimacy. It is also about the fact that these regimes have not been delivering—both within countries and at the level of the global order.

International cooperation on human rights is shrinking. By 2026, it is estimated to be 50 percent lower than it was three years ago. Support for independent journalists, NGOs engaged in strategic human rights litigation, and networks of young leaders seeking to promote democratic practices have declined dramatically. At the same time, other arenas have gained resources and visibility, with social media playing a major role in amplifying influence and reach. That is part of a different discussion, but the bottom line is that there is no longer sufficient power sustaining that contract. So, again, I am not sure this is a question of design; it is more fundamentally about power.

Illiberal Networks Exploit 21st-Century Tools While Democracy Speaks in 20th-Century Language

Your analysis highlights how liberal institutions’ commitment to proceduralism and neutrality can be exploited from within. Is this best understood as an institutional design flaw, a crisis of political will, or a deeper contradiction within liberal constitutionalism itself?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: This partially relates to what I just said: the lack of legitimacy and the lack of power. At the same time, I want to emphasize that the global arena is contested. There is no clear winner. It has always been contested, but there was once a clear predominance of liberal, pro-democracy, and human-rights–oriented international regimes, while alternative models were weaker.

Today, the illiberal camp is growing, and illiberal networks and actors are increasingly effective in using 21st-century tools—misinformation, the manipulation and circulation of information, and the construction of conspiracy theories that support their worldview and preferred version of facts. A particularly important turning point was the pandemic, which exposed how nation-states and the international order lacked sufficient capacity to respond effectively. This moment acted as a major trigger; for instance, it coincides with the period when Milei entered politics.

These actors have been highly effective in exploiting digital communication, narratives, and misinformation, which have proven especially appealing. In particular, they have successfully mobilized people’s disappointment and anger. When populations became frustrated by real-life experiences—lockdowns, unemployment, children being forced into online learning, and the collapse of healthcare systems—these grievances were skillfully leveraged to generate resentment toward democracy and politics more broadly.

They have also been effective in promoting narratives such as “we are outsiders,” “we are going to drain the swamp,” or, as Milei puts it, attacking la casta, the political elite portrayed as the worst. Meanwhile, the democratic camp continues to rely on 20th-century tools—narratives that resonated in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s but are no longer persuasive today.

Why should I pay my taxes if education continues to deteriorate? Why should I contribute to my pension fund if I will receive very little when I retire? We continue to invoke narratives of the social contract, welfare, and liberal rights when lived realities no longer fully align with them, or at least do so far less than before. Illiberal actors have been very effective at exploiting this anger and loss of legitimacy. As we all know, when people are angry, those who manage to tap into that emotion can manipulate their will.

Illiberalism Grows Where the Nation-State Loses the Power to Set Boundaries

To what extent should the rise of the illiberal international be understood as the product of structural transformations in the global political economy—such as shifts in GDP distribution, energy interdependence, and technological capacity—rather than ideological convergence alone?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: This is part of my own research, so I will not bring my co-authors into this. My work is precisely about this issue. I am fully convinced that the crucial challenge lies in the weakening power of the nation-state. As we know, democracy flourished only when there was a strong nation-state—institutions capable of placing boundaries on de facto powers, whether capitalist entrepreneurs seeking to maximize profits, illegal actors, large media conglomerates, or other forms of concentrated power. Democracy functioned more effectively when the state was able to exert some control over these forces.

What we have witnessed is a long-term erosion of this capacity since the 1970s, driven by the deregulation of the financial sector and neoliberal policies that diminished the role of the state. This was followed by a series of crises—from the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the household debt crises of 2008 and 2013 to, most significantly, the COVID-19 pandemic, which marked a profound transformation. Today, inequality is no longer defined by the top 1 percent; rather, it is the top 0.01 percent, whose wealth has grown by a thousand percent over the past decade, while the bottom 50 percent of the world’s population has seen living standards stagnate or even decline.

This also raises the issue of sovereignty—the ability to regulate transnational commerce and transnational information flows. With the rise of social networks, we now face an unprecedented situation: privately owned platforms such as Twitter or X, YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram function as their own media ecosystems, reaching billions of people worldwide. The lack of effective regulation means that these actors determine what is acceptable in public discourse, which voices are amplified, and which are marginalized.

All of these developments point to structural factors affecting sovereignty, the provision of public goods, and civic discourse—three key arenas of stateness. The problem is that nation-state institutions were designed for national boundaries, analog societies, and national markets, whereas today we inhabit digital, globalized societies. The central challenge, then, is how to rebuild political capacity—to recreate forms of stateness capable of regulating de facto powers in the current context.

Illicit Networks Spread as States Lose the Power to Enforce Rules

How central are illicit financial flows, money laundering, and transnational corruption networks to the reproduction of illiberal politics within formally democratic systems? To what extent should these networks be understood not merely as enabling mechanisms but as constitutive pillars of contemporary illiberalism, shaping political competition, institutional capture, and democratic hollowing from within?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: This is part of the same answer. These dynamics have always been present in liberal systems. Money laundering, drug trafficking, and weapons trafficking have long existed. What has changed is our capacity to control them. There is now less power to set and enforce rules.

As a result, these practices have, in a sense, spread. This is something we show in our article. There is no longer a clear “axis of evil” overseeing what were once perceived as isolated authoritarian or illiberal practices. Instead, these dynamics have become far more widespread. We now see even middle powers, such as Turkey or Hungary, exercising influence—for example, Hungary funding the Vox political party in Spain, or Vox supporting Kast in Chile.

This points to a broader diffusion of such practices and, at the same time, to fewer constraints, fewer penalties, and weaker deterrents against this kind of behavior.

When Norms Shift, Language Turns into Action

Events such as The Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) and “Make Europe Great Again” blur boundaries between conventional conservatism and authoritarian narratives. How does this discursive hybridization accelerate the normalization of illiberalism within democratic publics?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: There is a widespread diffusion of these practices that, again, were present before. Many of these ideas existed previously, but now they operate without constraints. The change—the normative shift in these cases—is crucial. It is crucial for redefining the boundaries of civic space and for determining what is considered acceptable or unacceptable in public debate.

These dynamics generate cultural change, and that cultural change is central in these arenas. It allows actions to follow that have meaningful impact. Although we might initially see this as merely a matter of language or narratives—about women, about feminists being labeled as fascists, and similar claims—there are people who act upon these narratives.

One striking example from a couple of months ago in Argentina involved a political activist of Milei who killed all the women in his family and was constantly mobilized by anti-feminist narratives. A similar dynamic can be observed in the United States with ICE and immigration, where many volunteers actively work for ICE.

That is what is changing. These networks, again, existed before, or at least similar networks existed, but they were marginal and could not operate so openly. Now they are visible, awarding prizes and running their own news outlets, and that represents a major change.

The Global Order No Longer Polices Illiberal Behavior

How do authoritarian or illiberal middle powers—such as Turkey, the UAE, Hungary, and Saudi Arabia—operate as brokers or hubs within transnational illiberal networks, and how does their intermediary role complicate binary distinctions between “core” and “peripheral” autocracies in the global authoritarian ecosystem?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: I have already touched on this, but I want to return to the issue of the erosion of the global order. In the past, at least, a middle power selling weapons had to ask for permission. Today, there is a much freer flow of such activities. For example, the Emirates selling weapons to rogue regimes, or Hungary funding Vox, as I mentioned earlier. There is far less control over these actions. As a result, it is no longer just the “axis of evil” that we used to think about 20 years ago. These dynamics are now widespread at different levels, and this reflects a broader shift in the balance of the global order.

Russia Disrupts, China Builds—and Democracy Must Respond Differently

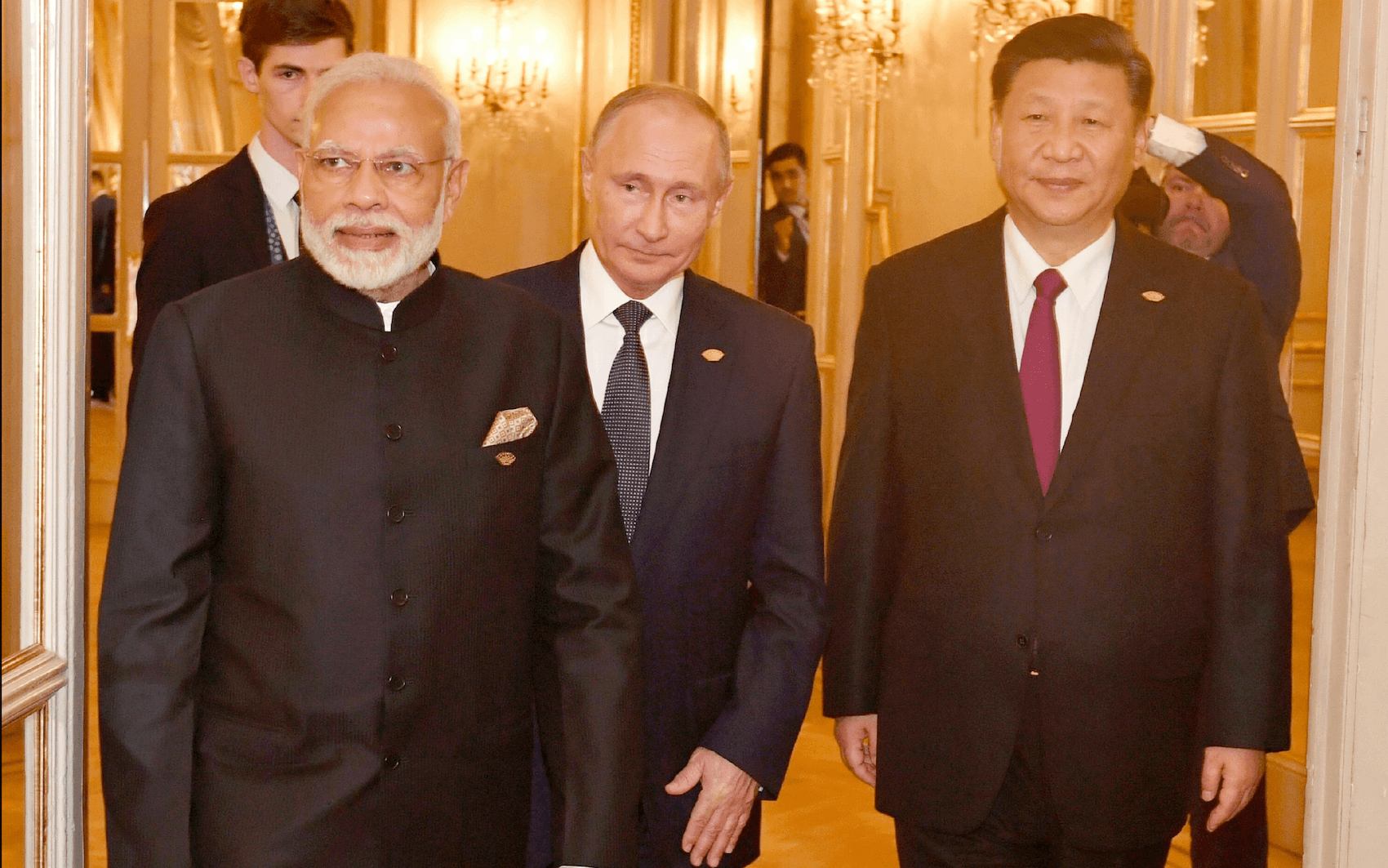

How do Russia and China differ in their modalities of illiberal influence—financial, ideological, technological, and diplomatic—and where do their strategies converge? How should we analytically distinguish Russia’s coercive and disruptive practices from China’s more institutionalized, developmental, and techno-governance–oriented approaches, and what do these differences imply for the design of effective democratic counter-strategies?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: That is a very good question. Russia has less soft power and relies more heavily on hard power, particularly through cyberattacks and arms sales. This calls for a specific set of responses, including stronger cybersecurity measures, better control over weapons distribution, and more effective countermeasures against disinformation.

China, by contrast, is more complex. It is the second-largest economy in the world and the largest foreign investor in roughly half of the world’s countries. Its influence operates largely through development investments, as you noted—building bridges, infrastructure, highways, and nuclear plants. This requires a different kind of response. The problem is that the United States and the European Union have been retracting from development investment. This is not only about recent USAID cuts; it has been happening for a long time. Meanwhile, China has been expanding the Maritime Silk Road through investment and trade, even in countries that are not particularly sympathetic to China’s political ideas, such as Chile under its new government, which nevertheless maintains very strong commercial ties with China.

This form of influence demands a different response—one based on greater investment and more credible policies. During the Pax Americana, the United States and Europe, in their hegemonic roles, often acted “under the table.” We should recall that the US funded many military coups in Latin America in the second half of the twentieth century, and that Europe has had deeply problematic practices in Africa for decades. This duality has always existed; it is not a simple story of good and bad actors. However, as Western actors retract and offer less, these contradictions become more visible and more damaging.

In this context, the risk is that some regimes are openly calling out what they perceive as the hypocrisy of Europe and the United States: “You are not offering as much as they are. They are building schools and infrastructure, and you are not.”As a result, democratic strategies must be different and more complex. It is not only about money; it is also about credibility—being credible in contracts and in international agreements. Credibility itself is central.

Democracy Must Be Made Attractive Again—Across All Levels

Are existing global and regional institutions reformable enough to confront the illiberal international, or do we need entirely new organizational forms?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: Political scientists are trained more to analyze past events than to forecast the future. But I would say that we need to look at the larger picture and think strategically. If we want to restore the strength of a liberal order based on human rights, respect for people, economic development, and a sense of equality and inclusion, we need to rethink how we build the political muscle to sustain it.

As I said before, in my opinion, the major crisis is that the institutional framework we have—the nation-state—lacks power. And it is not simply about going back to the nation-state. We need to restore ideas of stateness, sovereignty, the provision of public goods, and the creation of a civic community. The question is: what institutional frameworks, powers, and financial resources can sustain that? I feel that the nation-state alone is no longer sufficient. So the broader strategic challenge—the forest, not just the trees—is how we rebuild democratic power.

At the same time, we need to think about tactics. We need to make democracy more attractive, not by relying on the narratives of the 1950s and 1960s, but by speaking the language of our time and developing more appealing communication strategies. We need to strengthen networks of people who want to live in democracy, who still believe in it, and who want to defend it.

We need also to work at the geopolitical level, at the level of institutional networks, but also at the community and even individual levels. For example, in schools, we see emerging practices in different countries focused on critical thinking—teaching people to recognize when they are being exposed to misinformation or manipulation strategies, and to take a step back. At the same time, we need to think carefully about how we treat our neighbors, how we speak to our peers, and how we engage with our political opponents. I feel that, tactically, we need to think across these different levels where we can act, while at the same time conceptualizing and building new political power to sustain a rules-based, rights-based society.

Without a More Honest Global Order, Polarization and Conflict Will Deepen

And lastly, Dr. Bianchi, under what conditions could democratic coordination regain momentum, and what do you see as the most plausible best- and worst-case scenarios for liberal democracy over the next decade?

Dr. Matías Bianchi: I think the next decade will be highly contested. I feel that things could go very wrong. We currently have several wars underway, any of which could escalate at any moment. We also face irresponsible global leadership. In Washington, for example, the language toward China shifted four or five years ago; policymakers no longer speak of an adversary but of an enemy. With that mindset, things can indeed go very wrong.

We could face a severe scenario marked by war and increasing societal polarization—developments we have experienced before and that we do not want to return to. At the same time, the desire for order has not disappeared. Clearly, we need to build a better one: a more honest order, one in which the Global South has greater influence and in which power and resources are more equitably distributed.

The United States and Europe still have an opportunity to help shape the rules of this order. However, they need to understand that these rules can no longer be based on hegemonic dominance, or on the United States acting as a hegemon in particular. Instead, the focus must be on designing rules that meaningfully include emerging powers, especially China.

If this does not happen, current trends will continue: China will further distance itself from liberal institutions and expand its own alternatives—such as the BRICS and other trade and financial frameworks. This will only deepen a bifurcated global order. There is much that could be done with greater generosity and a stronger commitment to inclusion, particularly toward the Global South and Asia.