In exploring the socio-political dynamics behind white Evangelicals’ support for Donald Trump and right-wing populism in the United States, Professor Marcia Pally of New York University identifies what she calls a “double loss” experienced by this group. She explains that white Evangelicals face both economic and societal losses—challenges shared by many Americans—which are further intensified by their distinct struggles as a religious community. This “double loss,” Pally argues, is coupled with a “double suspicion” of government and “outsiders”: a widespread American distrust of centralized authority, minorities, and new immigrants, paired with a doctrinal suspicion rooted of priestly and other authorities in Evangelical religious beliefs.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In a thought-provoking interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Marcia Pally of New York University delves into the socio-political dynamics driving the support of white Evangelicals for Donald Trump and right-wing populism in the United States. Highlighting what she describes as a “double loss” experienced by this demographic, Professor Pally explains how both economic and societal losses—shared by many Americans—are compounded by the unique religious challenges facing white Evangelicals. This sense of loss, she argues, is accompanied by a “double suspicion” of government and of “outsiders” (minorities and new immigrants): a general American wariness of centralized authority, alongside a doctrinal distrust of priestly and other authorities and of “outsiders’ rooted in Evangelical religious teachings.

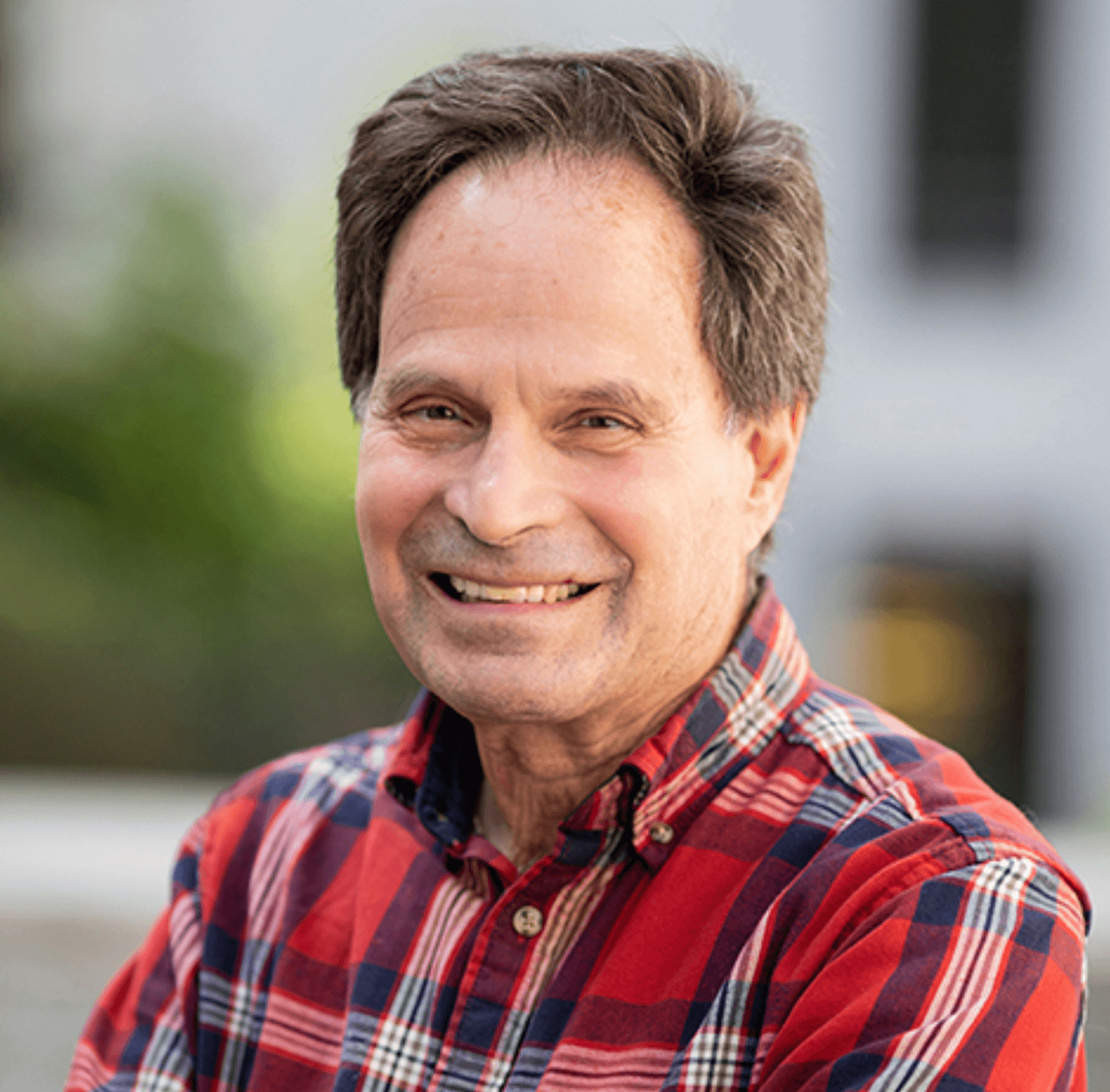

Professor Pally, an expert in theology and political culture, teaches at New York University and was awarded the Mercator Professorship in the Theology Faculty at Humboldt University, where she is an annual guest professor. She has authored several influential books, including White Evangelicals and Right-wing Populism: How Did We Get Here?; From This Broken Hill I Sing To You: God, Sex, and Politics in the Work of Leonard Cohen; and Commonwealth and Covenant: Economics, Politics, and Theologies of Relationality. Her work focuses on the intersection of religion, politics and society, making her a leading voice in understanding the socio-cultural underpinnings of right-wing populism in the US.

Throughout the interview, Professor Pally unpacks the role of white Evangelicals in American right-wing populism, tracing their political engagement to a deep-seated suspicion of government and of “outsiders” and to a perceived erosion of cultural influence. She elaborates on the phenomenon of “Christian nationalism,” a relatively recent term describing a political movement that uses particular readings of Christianity to justify nationalist goals. However, she notes, Christian nationalism is not truly a form of Christianity but rather a form of nationalism that taps into the anger that arises from significant socio-economic losses and cultural marginalization.

Professor Pally also addresses how Trump’s rhetoric and policies—particularly on immigration and national identity—resonate with white Evangelicals, drawing on long-standing cultural anxieties about “outsiders” and threats to community. Finally, she explores the global implications of Trump’s potential re-election, predicting that right-wing populist movements around the world would likely adapt his strategies and rhetoric to their own contexts.

In this wide-ranging conversation, Professor Pally provides a nuanced understanding of the political and cultural forces shaping the white Evangelical electorate and their continued support for Donald Trump’s populist rhetoric in the United States.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Marcia Pally with some edits.

Populism as a Response to Duress: Loss, Threat, Fear or Anxiety about Change

What key differences do you observe between left- and right-wing populisms in the US, in particular the role of Evangelicals in American right populism, and how do these movements draw differently from America’s religio-cultural history? Could you elaborate on the American religio-political background from which populist beliefs emerge, and explain how this historical and cultural trajectory influenced Trump’s election in 2016?

Professor Marcia Pally: That’s a series of very complex questions. Let me take them step by step. You asked about the differences between left-wing and right-wing populism. Let me begin by saying that, following prominent research, I’ve developed a minimal core definition of populism. Then we can talk about left, right, strong and weak variants. The core definition of populism is that it’s a response to duress: loss, threat, fear of loss or anxiety about changes in economic situations, ways of life, technology, demographics, gender roles, etc.

When these losses or fears accumulate, people naturally shift their focus outward. They move away from their usual preoccupations—family, friends, schools, teams—and focus instead on identifying a “them” who is perceived to be causing harm to “us.” This shift to an “us versus them” mentality is a normal human response. It’s not specific to Europe, America or any particular ideology—it’s a species-wide reaction to perceived threats.

The third prong in this response to duress is identifying “them.” Populist movements—especially right-wing ones—seek to identify those they see as causing the harm. This identification usually draws from culturally familiar “others,” which can differ from culture to culture or even subculture to subculture. For instance, in the US, we don’t hear much about the Roma people because they play a negligible role in American history. But in other parts of the world, the Roma people have been historically singled out as a “them” responsible for certain fears or harms.

The “them” in the “us versus them” dynamic draws from historical and cultural ideas about society–who is “in” and who is “out”– as well as beliefs about the proper role and size of government.

To sum up, we can define populism as driven by duress, leading to an “us versus them” binary, where the “them” is identified based on long-standing cultural and historical factors. The key difference between left-wing and right-wing populism lies in who the “thems” are. Right-wing populism traditionally identifies the “them” as outsiders—new immigrants, religious and racial minorities and sometimes a corrupt government.

Left-wing populism, on the other hand, doesn’t usually target the government, as the left often views democratic governments as representatives of the people and legitimate agents of governance. Instead, left-wing populism tends to focus on economic exploitation, rather than identity politics, and identifies “them” as those responsible for economic inequality rather than as racial, ethnic or religious minorities. So, one key difference is that the right is more suspicious of government, while the left sees it as a potential agent of positive change.

I should also note that populism is not a static concept; it exists on a continuum. On one end, you have softer forms of populism, which align more closely with the normal agonistic aspects of democratic processes. For example, Bernie Sanders or Martin Luther King Jr. could be considered proponents of “soft” populism, which stays within the realm of democratic debate.

As you move along the continuum, populism can grow stronger, characterized by a much sharper “us versus them” binary and a diminished tolerance for ambiguity. In softer populism, someone can be an ally on one issue and an opponent on another. For instance, a corporation might support climate change action but oppose raising the minimum wage, and soft populism would recognize this complexity as part of politics.

In stronger populism, however, the “us versus them” division becomes much more rigid, often framing the struggle as a battle between good and evil, with existential stakes. This can lead to more extreme and uncompromising solutions.

The second part of your question, about cultural history and its impact, was quite broad. Could you narrow it down so I can address it more specifically?

The Problems People Face Are Often Real and Justified

Can you elaborate on the role of Evangelicals in American right-wing populism?

Professor Marcia Pally: Sure. I’m going to break this down by distinguishing between white Evangelicals and Evangelicals of color, because their histories in the US are very different. Evangelicals of color have a rich and vibrant history that really deserves its own study. Since my research focuses on white Evangelicals, I’ll focus on them here.

White Evangelicals—and their ancestors—have been coming to the US since the 17th century. They’ve contributed to and participated in the development of the country and contributed to three of the most foundational aspects of American political culture.

First, there’s covenantal political theory, which views the governed as a covenanted community. In this theory, sovereignty rests with the people, not the king or a ruler. If the leader—what we might now call the President or Prime Minister—violates the covenant with the governed, it is seen as legitimate to remove them. This is a productive heritage, and the ancestors of today’s Evangelicals played a significant role in introducing this idea to the United States.

Second, they contributed to republicanism—with a small “r”—which comes from Aristotelian thought. It emphasizes that citizens run the polis or state. This idea also centers around community engagement and governance, with sovereignty rooted in the people themselves.

Third, Evangelicals played a role in shaping liberalism, which, while less focused on the community aspect, emphasizes individual opportunity. However, like the other two traditions, liberalism maintains a strong suspicion of any government or ruler that abuses power. This suspicion runs through all three aspects: A leader who violates the covenant with the people; a tyrant who attempts to take control of the republic; and a ruler who tries to constrain individual freedoms.

Evangelicals, like other immigrants, contributed to all three of these foundational elements of American political culture. Additionally, two other important factors shaped their current position on the right wing of American politics.

First, their doctrinal belief that all governments are flawed and imperfect—none embody the Kingdom of God—leads them to be wary of authority. Each person, they believe, must determine how to live a moral life and foster a moral society, reinforcing their suspicion of centralized authority.

The Evangelicals we’re discussing are Protestants, heirs of the Protestant Reformation, which emphasized the individual conscience in developing a moral life and society. They are skeptical of priestly authority and instead trust the individual’s conscience. This, again, amplifies their wariness of government. This may foster the fear that the government could violate their covenant, their republic, their liberal rights and their doctrinal obligation to uphold the moral life. This suspicion also extends to outsiders who might interfere with their way of life.

This skepticism can be positive: a healthy distrust of government can guard against authoritarianism, bolster democracy and promote individual opportunity. Their strong sense of community has been a key factor in local development and community engagement. This commitment to community and localism is part of a long tradition in the US, especially within Evangelical circles.

However, under duress, things change. The usual focus on community and democratic localism can shift outward, leading to suspicion and fear of outsiders. Under pressure, the commitment to community may flip into an “us vs. them” mentality, where outsiders are perceived as threats to the community. Similarly, a healthy suspicion of autocratic government can morph into a blanket distrust of all government. Under stress, people tend to look for a “them” to blame for their problems, and nuanced thinking can give way to simplistic explanations.

Under these conditions, a suspicion of autocracy turns into a general suspicion of government, except when government is used to constrain outsiders. This shift makes it difficult for society to function effectively—if government is distrusted and outsiders are seen as threats, collaboration and compromise are stifled. If the government itself is seen as inherently suspect and if outsiders—who often bring talent, innovation, and entrepreneurialism—are also viewed with suspicion, a final tragedy emerges. This shift in perception, from community cohesion to distrust of outsiders and from a healthy skepticism of tyrants to a blanket suspicion of all government, leads to a loss of nuance in understanding the original sources of duress.

In today’s interconnected global economy, with its complex networks of transportation, communication and technology, problems such as economic hardship or changes in ways of life often have multiple, intertwined causes. This complexity can be overwhelming, leaving individuals feeling powerless to address the issues. In this context, the “us vs. them” mentality offers a simple explanation by blaming an identifiable group for the strain.

However, this appealing simplification can prevent people from recognizing the more intricate, systemic causes behind the challenges they face. In my research, I have found that the problems people experience are often very real and justified—people are generally aware when they are being impacted. The tragedy is that, if they can’t properly identify the true causes of their struggles, they may misdirect their frustration and fail to address the root issues.

Nothing Trump Said Is New in the American Cultural or Political Context

We know that it is not only Trump but other Republicans as well addressed economic and way-of-life duress but what made Trump’s policies so effective and ‘persuasive’ in garnering the votes? In what ways does the evangelical sense of cultural and political marginalization influence their embrace of Trump’s rhetoric and policies on immigration and national identity?

Professor Marcia Pally: This is a complex question but let me address it step by step.

First, it’s crucial to recognize that nothing Donald Trump said was new in the American cultural or political context. His identification of the “deep swamp,” the insider elite in Washington and the so-called elite media or “fake news,” is not new. It’s an expression of the long-standing suspicion of government in the US. As I’ve mentioned, this suspicion has a healthy, democratic side but can also morph into a general distrust of government. Trump was able to tap into this long-standing element of American political culture.

Similarly, regarding outsiders—whether new immigrants, religious minorities like Muslims or occasionally even anti-Semitic themes—Trump was able to activate these entrenched cultural anxieties. When you ask why he was so effective, it’s because he tapped into sentiments that had existed for a long time. In the 2015–2016 campaign, he experimented with different slogans to see what resonated, and when he received applause for certain themes, he kept using them.

When a political message touches on a long-standing concern—one that feels familiar or “right” to people—it’s likely to gain traction. Trump successfully tapped into both anti-government and anti-outsider sentiments and he continued to use those themes because they worked. But it’s important to emphasize that these ideas were not new.

For example, “America First” was not Trump’s invention. Woodrow Wilson used the phrase in 1916 in his efforts to keep the US out of World War I. Senator William Borah from Idaho also used it to argue against US involvement in the League of Nations after the war.

Similarly, “Drain the Swamp” was not Trump’s creation either—it was a campaign promise used by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s.

Now, for the second part of your question regarding evangelicals, could you clarify what specifically you’d like me to follow up on?

In what ways does the evangelical sense of cultural and political marginalization influence their embrace of Trump’s rhetoric and policies on immigration and national identity?

Professor Marcia Pally: Thank you for that. Let’s return to our core definition: duress and the “us vs. them” shift through culturally familiar themes.

The pressures that white Evangelicals face are real and legitimate concerns. White Evangelicals experience the same duress many Americans do. There has been a loss of purchasing power since the 1980s, a decline in unionization and the disappearance of jobs for which Americans had been trained, alongside insufficient training for new jobs emerging from new technologies. Health care, housing, education, day care, senior care are all expensive for middle- and working class- Americans. Rapid technological advancements and changes in gender roles have also contributed to the sense that life today is harsher and more difficult than it was for their parents or grandparents.

There’s a growing sentiment that life has become less fair. People work hard, yet they lose their jobs or find themselves underemployed and communities are devastated when factories close or, more significantly, when technological changes increase productivity, reducing the need for workers. These are legitimate, very real hardships and neither political party did much to address them—until the Obama and Biden administrations, which took several productive steps, though not enough.

In addition to these economic hardships, Americans face “way of life” losses. By this, I mean the sense that one’s standingas respectable, middle-class individuals is being eroded or undermined. They feel powerless to change this, as policies are made by distant decision-makers who seem out of reach and unaccountable. These complaints are quite real.

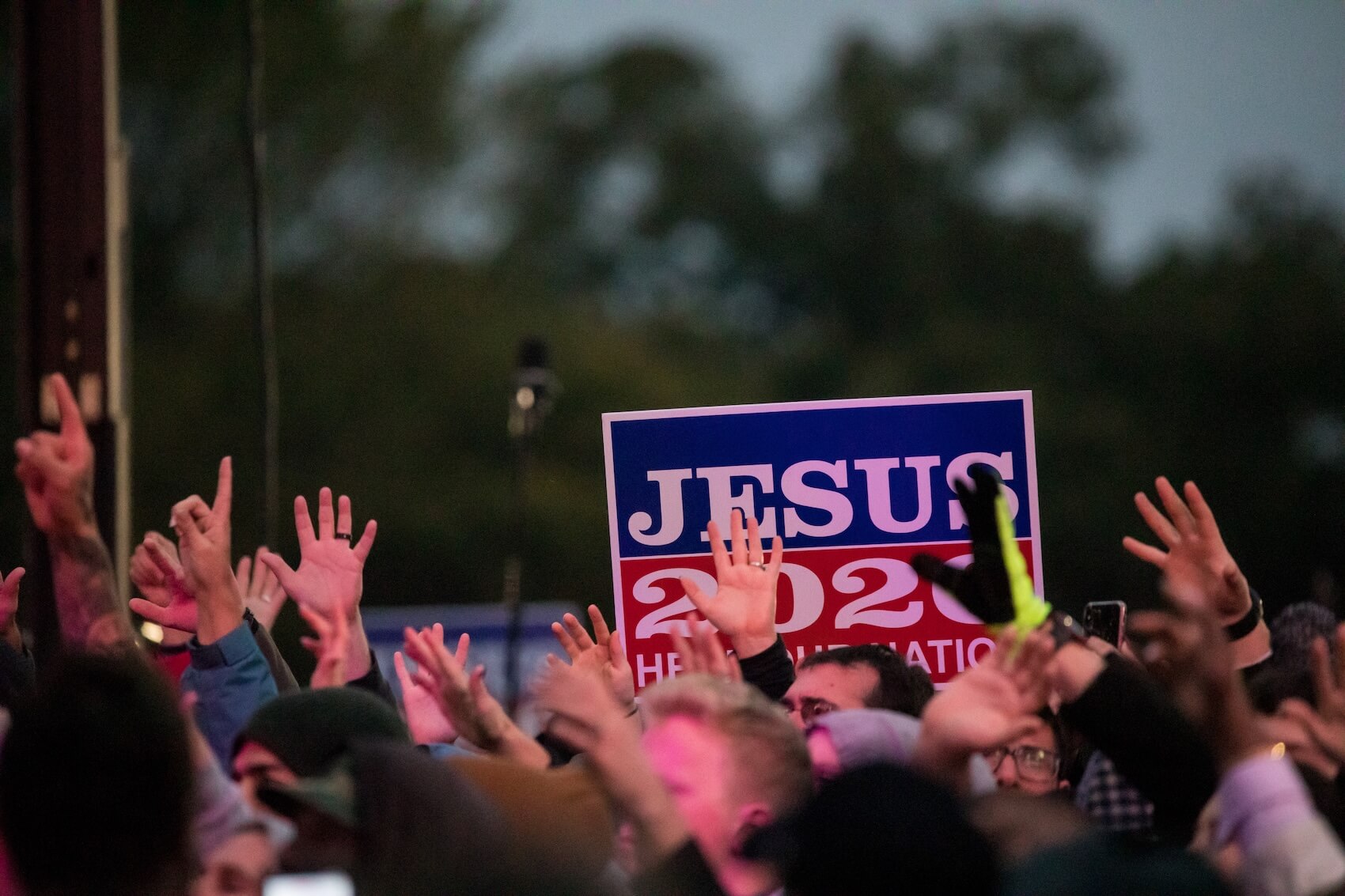

On top of that, white Evangelicals have suffered a demographic loss. In 2004, they made up about 23–25% of the population; today, they are roughly 13%. They are the most aged of all religious groups in America, with an average age of around 56, and there is a growing fear of losing cultural influence in the US.

White Evangelicals once held more “soft power,” or cultural sway, in American life. As society has become more secular, urbanized and socially progressive, they’ve seen a decline in their influence. These demographic and cultural losses are felt as real and painful, compounding the economic and social changes that many in the middle and working classes are experiencing.

In summary, Evangelicals face a “double loss”: the economic and societal losses many Americans endure and the unique losses faced by their religious group. This double loss is paired with a “double suspicion” of government and “outsiders”—both the general American wariness of centralized authority and “others” (minorities, new immigrants) and the religious, doctrinal suspicion of priestly and other authorities.

This combination of double loss and double suspicion, particularly under duress, creates a volatile situation. When people are under pressure, they look for a “them” to blame and they turn to familiar explanations for their very real difficulties—ones that are culturally familiar, understandable, and resonate with their lived experiences.

You underline that in late 2019, the influential, mainstream evangelical publication, Christianity Today, ran an editorial calling for Trump’s removal from office. Yet in the 2016 presidential election, 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for Trump. How do you explain this strong bond despite forceful Evangelical reservations?

Professor Marcia Pally: It’s important to remember that Americans, in general, are suspicious of authority and evangelicals are doubly so. While Christianity Today is an influential magazine, an editorial it publishes doesn’t dictate how evangelicals across the country will respond. Evangelicals are likely to make up their own minds, based on their individual assessments of the situation, their personal sense of duress, loss or threat, and their views on the root causes of these challenges.

I’m not at all surprised that a major, influential magazine would criticize Donald Trump and declare him unfit for office, while at the same time, a substantial portion of evangelicals make their own decisions, grounded in their own perspectives and evaluations.

Christian Nationalism Is Not a Form of Christianity, but a Form of Nationalism

Can you elaborate on the concept of “Christian nationalism” and how it has been employed by White Evangelicals to justify their support for Trump and right-wing populism?

Professor Marcia Pally: Christian nationalism is a relatively recent term and it’s an important one, developed by colleagues of mine who have done excellent work. However, I’m not convinced that white evangelicals are actively using Christian nationalism. It might be more accurate to say that Christian nationalism is using white evangelicals. Let me explain.

First of all, Christian nationalism is not a form of Christianity; it is a form of nationalism. The core of it—the noun—is nationalism.

Christian nationalism aims to implement specific political, economic and social policies. It is a political position, not a faith tradition that aligns, for instance, with the teachings in Matthew 25, which calls for caring for “the least of these.” Rather, Christian nationalism is a political ideology that its proponents claim is justified by their particular readings or interpretations of Christianity.

Adherents of Christian nationalism argue that their political stances are rooted in their understanding of Christian doctrine and the Bible. However, it’s crucial to note that many Christians in the US have vastly different interpretations of Christianity. These Christians are working tirelessly to promote other understandings of the faith. This includes 20–25% of white evangelicals, whose voices are often underrepresented in mainstream media. They are actively advocating for alternative interpretations of the Bible and the Christian doctrine.

It’s also important to point out that Christian nationalism is not a uniquely white evangelical invention or “brand.” The movement extends far beyond white evangelicals, encompassing individuals from the broader religious right, including Catholics and mainline Protestants. So, while some white evangelicals may identify with Christian nationalism because they align with its “us vs. them” themes, it is a much broader political movement that goes beyond just one group.

How do you think right-wing populism will be affected globally if Trump gets elected on November 5?

Professor Marcia Pally: Right-wing movements around the world communicate with one another. Of course, this is not unique—left-wing movements, centrist movements, governments and NGOs also communicate globally. This is to be expected.

Given that right-wing populist movements exchange ideas and strategies, closely observing each other’s successes and failures in order to learn from them, if Trump is re-elected in November, I expect right-wing groups and leaders—or those aspiring to leadership on the right—to examine the strategies, rhetoric and promises of Trump’s campaign. They will likely try to adapt and apply these approaches within their own political contexts.