Please cite as:

Lipiński, Artur. (2024). “Dashed Hopes and the Success of the Populist Right: The Case of the 2024 European Elections in Poland.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0079

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON POLAND

Abtstract

The European Parliament elections of 9 June 2024 were the next stage in the electoral marathon started by parliamentary elections in 2023 and local elections earlier in 2024 and ended with a good result for the populist Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) and the radical-right Confederation of Freedom and Independence (Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość), confirming the relevance of right-wing populist parties in Poland. The combined electoral outcome of both PiS (36.16%) and Confederation (12.08%) is only slightly below 50%. The hopes of all those who treated the 2023 parliamentary elections in Poland as a victory over populism, paving the way for more victories, were thus dashed. The report aims to highlight the political and social context that led to these results and offer arguments supporting the classification of PiS and Confederation as populist communicators. The subsequent sections analyse the political communication strategies employed by both parties, emphasizing the intricacies of their discursive articulations concerning national and European themes. Lastly, the report explores the correlation between the political agendas of PiS and Confederation and the thematic preferences of their electorate, offering a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play.

Keywords: Law and Justice; Confederation; populism; EP elections; right wing

By Artur Lipiński* (Department of Political Science and Journalism, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland)

The European Parliament elections on 9 June 9 2024, the next stage in the electoral marathon started by last year’s parliamentary elections and this year’s local elections, ended with a good result for the populist Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) and the radical-right Confederation of Freedom and Independence (Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość) usually referred to simply as Confederation (Konfederacja). The hopes of all those who treated the 2023 parliamentary elections as a victory over populism, paving the way for more victories, were thus dashed. Although Prime Minister Donald Tusk and the ruling Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, PO) framed this election as a contest between his coalition and all parties – including PiS – over the fate of the EU, PiS was still able to secure 36.16% of the vote despite low turnout in the countryside, where voters disproportionately favour PiS.

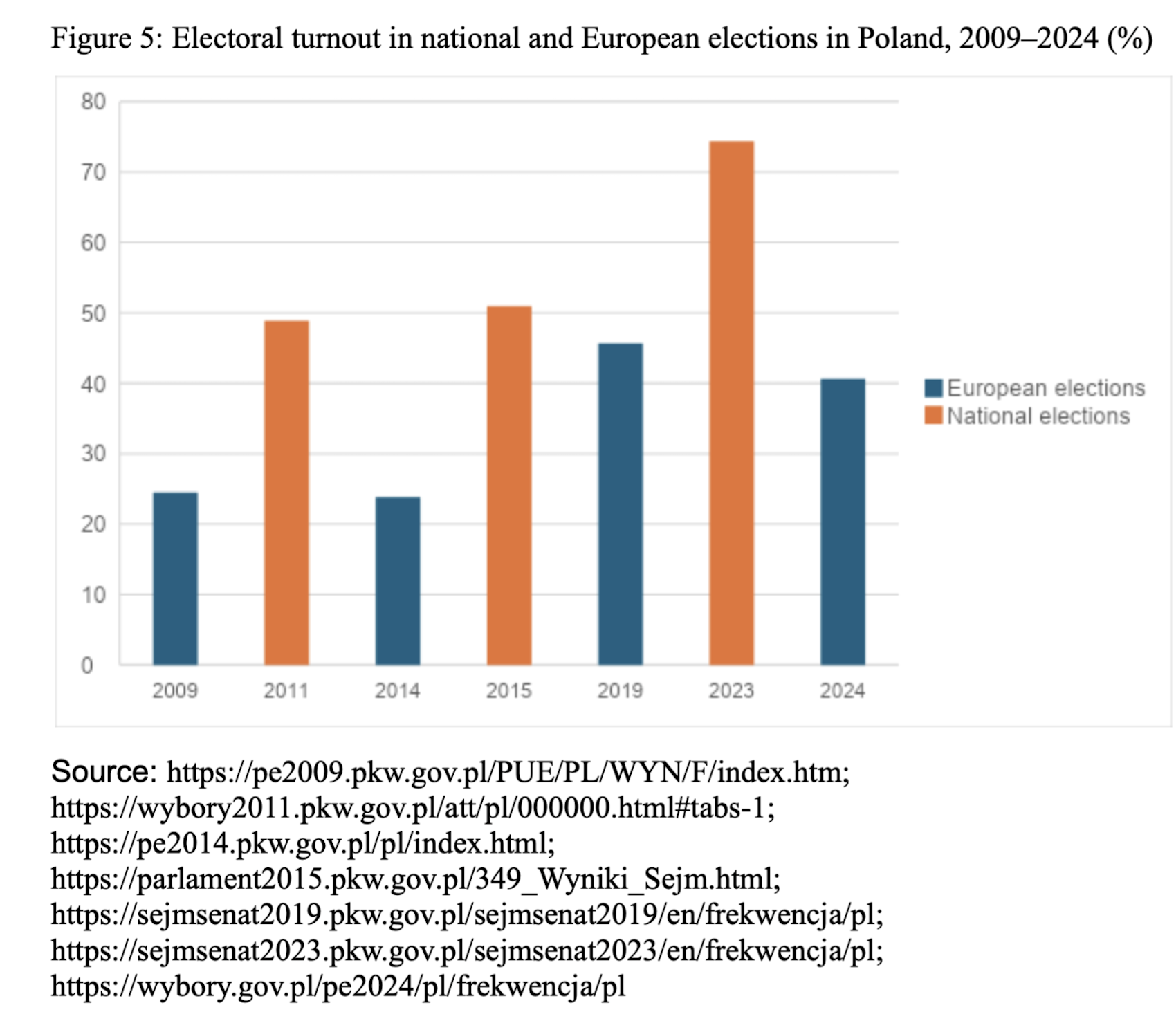

The elections also confirmed several findings by researchers that consider the EP elections to be ‘second-order’ elections. First, these elections are assumed to be less salient for voters as they do not influence national government formation. In fact, in Poland, the high turnout from the 2023 elections, mainly due to young people coming out to vote, led to the success of the liberal opposition at the time, was not repeated and mainly a hardcore electorate went to the polls. Second, the assumption that these elections favour parties of the radical right was confirmed, as they provide a credible and adequate context for articulating Eurosceptic and nationalist views. In the case of Poland, this meant the relative success of the radical-right Confederation, which has made explicit criticism of the European Union its hallmark. Third, there is the question of whether national themes predominate over pan-European ones in elections for the European Parliament. The assumption is that EP elections tend to reflect conflicts and rivalries within the domestic political arena rather than issues dealt with by the European Parliament. However, as this report details, it was not necessarily so in the 2024 EP elections in Poland, as national and European issues were articulated together, contributing to the larger discourse on Europe, its institutions, values and policies.

The main populist actors and their results

The results of the 2024 EP elections confirmed the relevance of right-wing populist parties in Poland. The combined electoral result of both PiS (36.16%) and the Confederation (12.08%) is only slightly below 50%. Out of these two, PiS constitutes a ‘quintessentially populist’ party (Stanley, 2023), not only with respect to its discourse but also in promoting and subsequently implementing policy solutions. If one adopts the widely shared view that populism is a kind of discursive logic that pits the people against immoral and corrupted elites, then PiS definitely has a populist character. PiS constructs a moralized dichotomy by positioning the traditional Christian nation against the ‘post-communist’ or ‘liberal’ elites (Bill, 2022). A significant element of PiS’s agenda includes anti-migration themes, which have contributed to the politicization and discursive shift in the public sphere since the so-called ‘migration crisis’ of 2015. This shift has led to the normalization of racist discourse and the securitization of migration issues (Krzyżanowska & Krzyżanowski 2018; Krzyżanowski 2020).

At the level of political action, populism combines colonization of the state with mass clientelism and discriminatory legalism (Müller 2016). Accordingly, after taking power in 2015, PiS immediately started dismantling institutional checks and balances, including the Constitutional Tribunal and Supreme Court and transformed the public broadcaster into the government’s mouthpiece (Sadurski, 2019). At the economic level, the party promoted generous social transfers, which not only allowed it to garner the support of beneficiaries but also to accuse political opponents of neglecting the people’s interests.

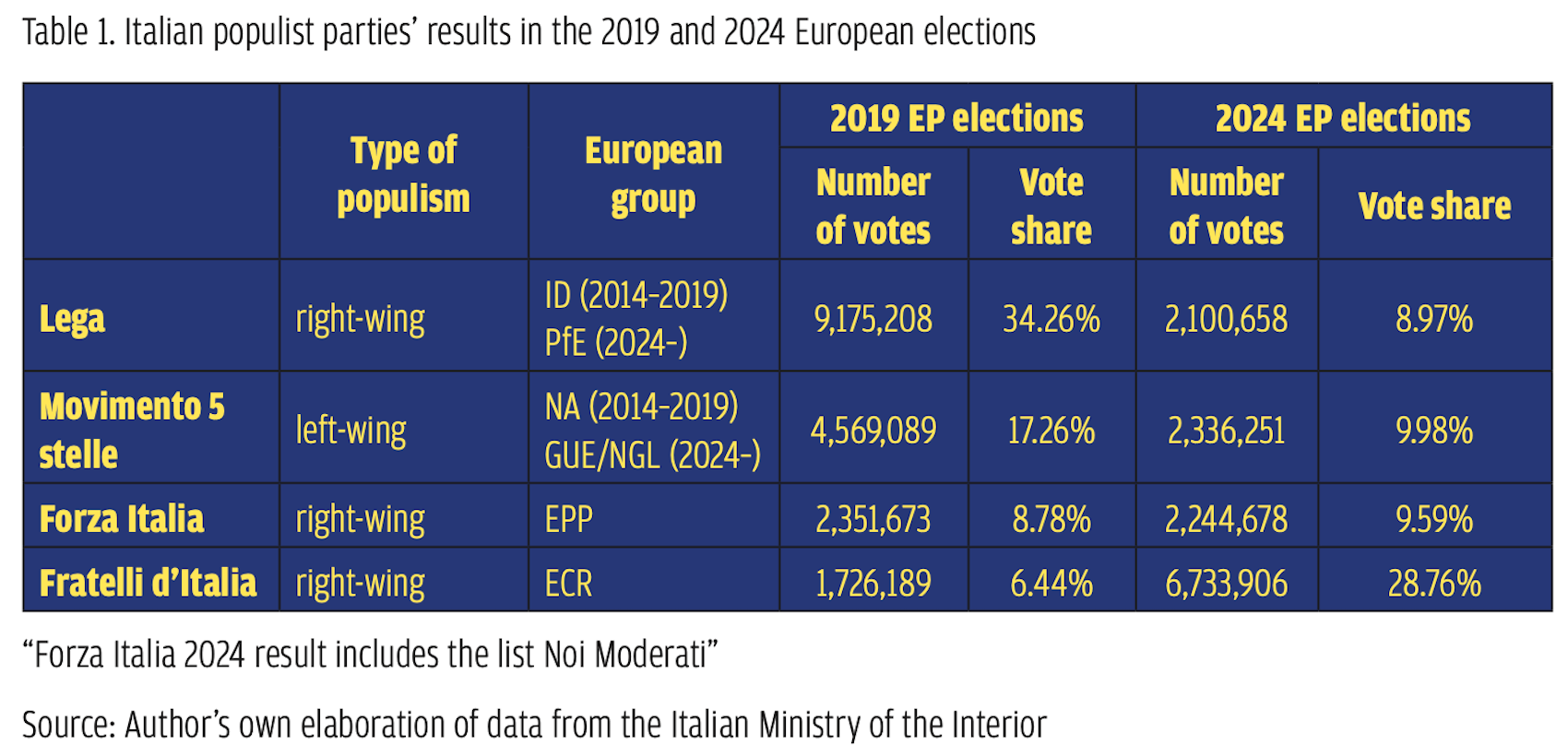

Such a populist formula allowed PiS to win a number of elections. In 2015, the party gained 37.5% of the votes, translating into 235 seats in the 460-member parliament, enabling the party to form a majority government that introduced all the changes it promised during the campaign. The expensive social transfers made after 2015 and further financial promises, as well as the rhetoric of threats targeted against LGBTQ+ people, secured PiS very good electoral results in the European Parliamentary elections in 2019, namely 45.4% of votes and 27 seats in the EP. The parliamentary elections held the same year brought PiS another victory; the party secured 43.6% of the votes and took 235 seats. It was exceptional not only in terms of the vote share, the highest for any political actor after 1989, but also in terms of the reelection for the second term with the overall majority (Szczerbiak, 2023). The ruling of the Constitutional Tribunal, an institution widely perceived as fully controlled by PiS, to introduce further restrictions into already harsh abortion law coupled with the series of financial and legal irregularities of PiS’s politicians systematically revealed by the media as well as the growing inflation contributed to the visible drop in public opinion polls. Although in the next parliamentary elections held on October 2023, PiS obtained 35.4% of the votes, it did not translate into the majority of the votes in the Sejm (the lower chamber of parliament), and the party was not able to form a government.

The second of the relevant right-wing actors is Confederation. Its classification poses decisively more challenges. Although The PopuList (Rooduijn et al. 2019) classifies the grouping as far right and Stanley (2023) adds that it is of libertarian rather than populist orientation, two caveats should be made here. Formally, the Confederation is a coalition of several parties that represent diverse views and target different segments of the population. New Hope, led by Sławomir Mentzen, is a libertarian party with a strong focus on economic issues, advocating for tax system simplification, tax cuts and neoliberal economic freedoms. Confederation also includes the National Movement, led by Krzysztof Bosak and the Confederation of the Polish Crown, founded by Grzegorz Braun. These groups combine (ethno)nationalism with moral and cultural conservatism, Euroscepticism, antisemitism and anti-Ukrainian sentiments. At least the latter two promote a nationalistic vision that merges anti-establishment rhetoric with the demonization of various groups. Additionally, as strategically calculating organizations, these political groupings adapt their communication strategies to the evolving political landscape and emerging challenges (Van Kessel & Castelein, 2016).

Since 2019, Confederation has slowly and consistently moderated its agenda, foregrounded free market aspects of its identity and economic discourse, dropped its antidemocratic messages and backgrounded or removed its most controversial figures. One crucial step was replacing the controversial leader Janusz Korwin-Mikke with Mentzen, a 35-year-old businessman and lawyer, and changing the name of one of the coalition parties ‘KORWiN’ to New Hope. Moreover, broadening the palette of the party communication with populist themes combined with populist performative strategies (like ‘beer with Mentzen’, a series of events organized across Poland when one of the leaders takes the stage with a mug of beer and talks about his political views emulating relaxed convention of stand up comedy genre) plus the skilful usage of the social media (with his 40 million views and 700,000 followers, Mentzen was the most popular Polish politician on Tik Tok) allowed the party to cross electoral threshold and to slowly build its popularity, particularly, among youngest cohorts of the electorate.

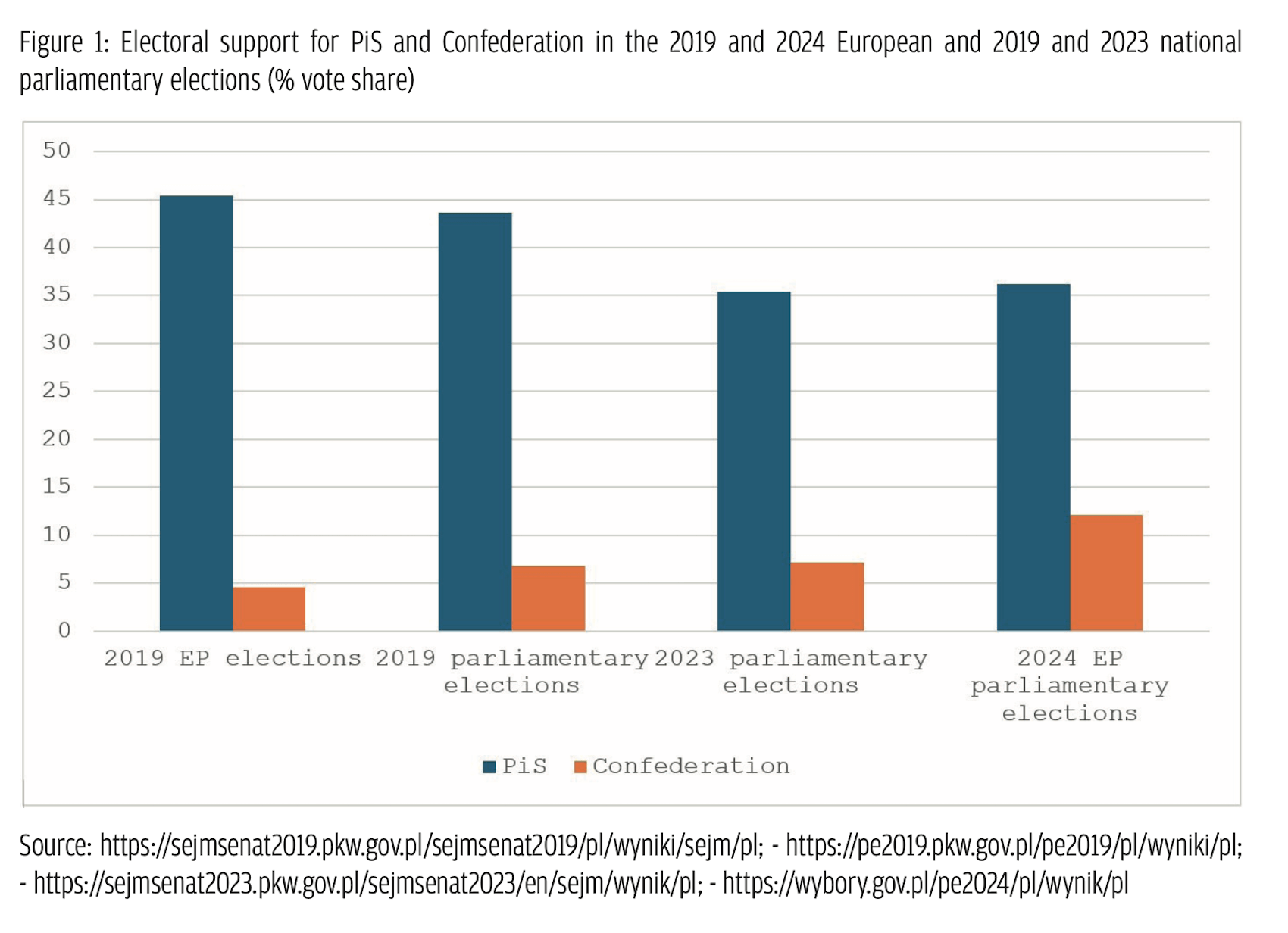

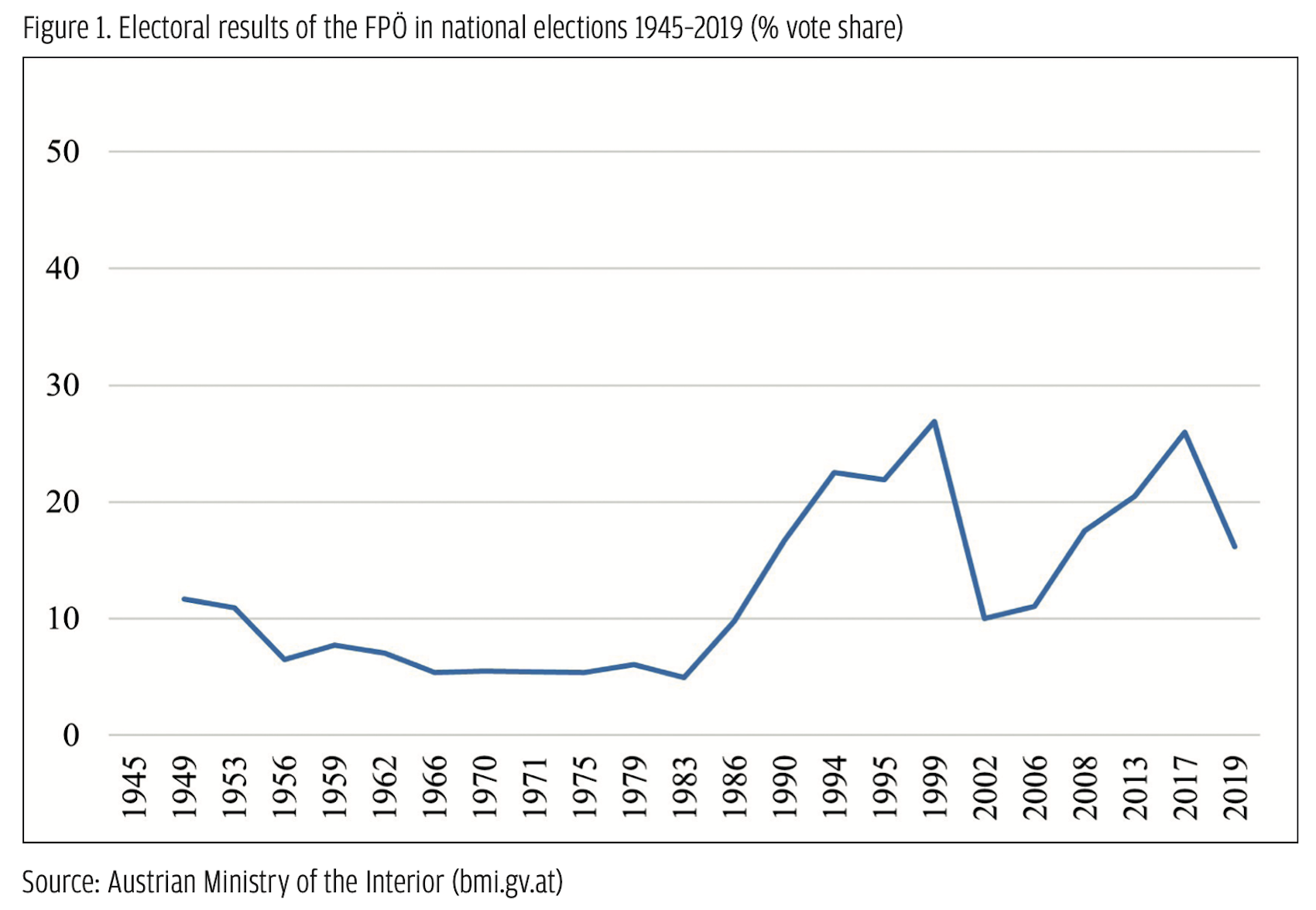

Confederation’s initial attempts to win public support through radical and controversial messages underpinned by antisemitism (Mentzen’s so-called Five Points: ‘we don’t want Jews, homosexuals, abortion, taxes and the EU’) did not bring the party satisfactory results in the 2019 EP elections. The grouping fell below the electoral threshold, receiving only 4.6% of the votes (see Figure 1 below). That led to significant moderation in the October 2019 parliamentary elections and 2020 presidential elections, with communication that emphasized the economic agenda and radical background content, which enabled Confederation to get 6.8% of the vote and win 11 seats in the 460-member Sejm. In the middle of 2022 the party experienced a slump in public support due to its implicit anti-Ukrainian agenda, manifested in references to the dramatic and sensitive aspects of Polish–Ukrainian history (the Volhynian massacre, in particular) and emphasis on the differences in the two states’ national interests. Confederation also chided the PiS government for its overly generous aid for Ukraine. This stance – alongside the extreme polarization between PiS and PO that left no space for smaller actors and the (social) media activity of critical journalists that exposed the radically conservative and exclusionary programmatic assumptions of Confederation – may have influenced the lower-than-expected double-digit result in the 2023 parliamentary elections, which ultimately saw Confederation take 7.2% of the vote (see Figure 1 below).

Confederation nearly doubled its support in the subsequent 2024 European Parliament elections. This increase was attributed not only to the ‘second-order’ nature of the elections, which in many countries bolsters the radical right, but also to the favourable opportunity structure created by various contextual events related to European and domestic affairs in Poland.

Campaign communication, populism and 2024 European Parliamentary election

The international and domestic context

At the international level, a few key issues have been heavily politicized and used as campaign themes by PiS and Confederation. First is the European Green Deal, introduced in 2019, which aims to achieve climate neutrality in the EU by 2050. This policy package is ripe for political exploitation due to its likely uneven impacts on the budgets of households, businesses, industries, regions and member states. Secondly, the European climate and energy agenda might be easily represented as led by the European elites against the sovereign decision of the member states. Additionally, being the result of very complex decision-making based on even more complex scientific expertise makes it even more vulnerable to political exploitation and populist argumentation.

Another important issue which affected the Polish public debate was the European Council’s approval in May 2024 of the EU Pact for Migration. The most controversial aspect of that was the so-called ‘solidarity mechanism’, which Poland’s populist right framed as a false choice between accepting an unspecified number of immigrants or paying €20,000 per immigrant. This framing ignored the option of negotiating alternative forms of support.

The backlash was further fuelled by the tense situation at the Polish–Belarusian border, where Belarusian President Alexandr Lukashenko’s regime transported foreigners from Africa and Asia to the border and forced them to cross. Both attempted and actual illegal crossings were met with a harsh and legally questionable response from the previous PiS government, a policy continued by the PO-led government after October 2023. This response included pushbacks, the introduction of the state of emergency, but also the idea of building the 187-kilometre-long physical wall and the electronic barrier equipped with cameras and motion detectors. These measures were justified by a strong anti-Muslim and orientalist discourse, introduced and normalized by PiS during the 2015’ migration crisis’, which reduced refugees to stereotypes of illegal Muslim migrants intent on imposing their values or posing a terrorist threat.

The outbreak of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 and the resulting influx of refugees, of which approximately 1.5 million have stayed in Poland, constitutes another dimension of context for the campaign communication (Duszczyk, Górny, Kaczmarczyk & Kubisiak, 2023). First, the populist right-wing government expressed a welcoming attitude towards Ukrainian refugees, granting them temporary protection, including access to the Polish healthcare system, schools and the job market, which stands in stark contrast with the Islamophobic and anti-migration discourse targeting refugees from the Polish–Belarusian border. Secondly, however, with the lapse of time, sociologists have observed some signs of growing compassion fatigue towards refugees staying in Poland yet in the second half of 2022, which makes the Ukrainian issue extremely vulnerable to politicization by radical populist parties (Sadura & Sierakowski, 2022; Baszczak, Winckiewicz & Zyzik, 2023).

Finally, two events preceded election day and strongly affected the discourse of the opposition. First, Onet, a leading news website, reported on 5 July that at the end of March and early April, three soldiers were detained after firing warning shots around a group of 50 people who were trying to cross the Polish–Belarusian border (Wyrwał & Żemła, 2024). The media information about detention coincided with the death of a Polish soldier on the same border, stabbed through the border fence with a knife attached to a pole and thrust in the direction of the soldiers by an unidentified man from the Belarusian side. The incident was part of a series of attacks and a surge in attempts at illegal crossings by migrants supported and forced by Belarussia and Russia. It created the discursive opportunity for the right-wing opposition, which accused the Tusk government of detaining the Polish soldiers responsible for the protection of the border and creating the freezing effect regarding the use of firearms for self-defence, which allegedly led to the death of the soldier.

The political communication of PiS

PiS was consistent in keeping its ambivalence towards the EU, which was determined by the still strong popular support for EU membership, but on the other hand, it was blackmailed by the Eurosceptical, if not Eurorejectionist, agenda of Confederation. The tone of the campaign was set at the party convention on 27 April 2024, during which Jarosław Kaczyński declared that: “We are Poles, and we have Polish responsibilities. Our red and white team is entering this election, this great undertaking, with full conviction and full determination that we must defend Polish values, Polish interests and the Polish raison d’etat. This means taking up the issues of the Green Deal, the migration pact, the change of treaties, the euro, the protection of the Polish countryside, security and, finally, what is the essence of Polishness – freedom” (Kaczyński 2024).

It clearly reveals the basic premise, lists the key issues of the campaign and informs about the master frame, providing the angle from which each of the listed issues was to be perceived. The contradictory relationship between national and European interests was perceived as a threat to freedom, which in the majority of contexts was understood as a right to absolute, exclusive sovereignty. During the convention inaugurating the campaign, the party presented a declaration containing a series of negative slogans exhibiting its attitude toward the EU: “We will cancel the Green Deal, stop the migration pact, stop the new treaty, defend the zloty, defend the interests of the Polish countryside in the EU, strengthen Poland’s security and armaments, and defend Polish freedom. […] The most important values to us are the welfare of the Fatherland and a better life. We are going to the European Parliament to defend the Polish national interest’” (aja/X, 2024).

At the forefront of the listed issues was the European Green Deal, which the party portrayed in its communication as an ideological project of the EU elites aimed against ordinary citizens. As the party has argued, higher energy and transport prices will raise costs for ordinary Poles as well as for businesses and housing construction. Further, it will have a substantial impact on agriculture: ‘Imposing so many different burdens on agriculture will lead to it first being in a very deep crisis, and in the long run, it will simply disappear’ (Tak dla polskiego rolnictwa, 2024).

The construction of crisis and the politics of fear, discursive mechanisms typical for the populist right, were also employed to represent the Pact on Migration, which was labelled as a ‘Trojan horse introduced to Europe’, a ‘particularly dangerous’ solution, and an ‘ideological project’ that would allow the EU elites to impose any number of migrants or punish Poland with financial penalties. It was further claimed that the Pact on Migration would lead to uncontrolled, massive immigration that would eventually change the demographic structure of Europe, destroy national cultures and adversely affect the security of Poles. As Kaczyński claimed: “Wherever this phenomenon of illegal immigration appears, but also where this immigration has been legal for many years, we are dealing with such zones where basically no law applies, where one is afraid to leave his house even during the day” (PiS, 2024a).

Moreover, campaign communication also contained many warnings regarding European treaty changes, which, if implemented, would lead to the centralization of the EU (conceived as German domination), complete erasure of Polish sovereignty and a threat to the national security and personal freedoms of ordinary people. Occasionally, the communication adopted a hyperbolic tone with the supposed adverse developments represented as part of the large plan of Western states, elites, ideologues, bureaucrats and lobbyists in collaboration with national elites to control weaker states in order to change their culture and exploit their economy: ‘Poland will no longer be a state, but simply an area of inhabitation of Poles. An area of inhabitation of Poles managed from outside’ (PiS, 2024d).

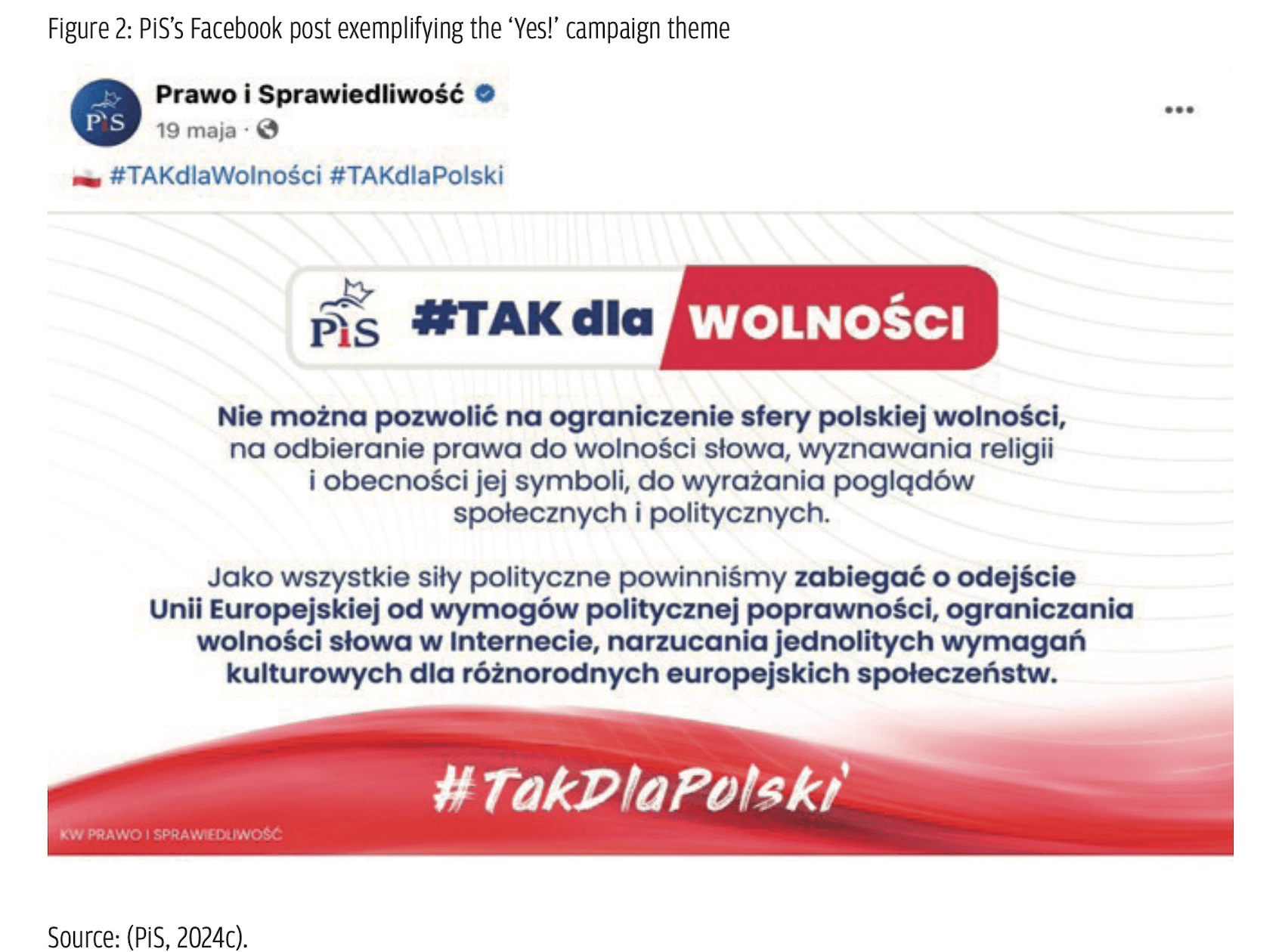

Interestingly, being aware that such communication exposed the party to the accusations of merely negative campaigning and planning to withdraw Poland from the EU, PiS attempted to reframe its message in a positive way. In particular, in the second part of the campaign, it promoted a series of ‘Yes’ slogans, for example: ‘#Yes for Poland!’, ‘#Yes for the Polish countryside’, ‘#Yes for investments’ or ‘‘#Yes for the defence of Polish borders’ (PiS, 2024b).

The party also explicitly declared its attachment to the EU and distanced from the Eurorejectonist slogans by emphasizing its vision of the Europe of Fatherlands as opposed to the populist perception of Europe as the elitist project targeted at the sovereignty and freedoms of ordinary people. Interestingly, although the security issue was an important part of the agenda, the war in Ukraine did not feature prominently in the campaign. In the end, the party used the incidents on the Polish–Belarusian border to articulate this issue together with the anti-migration discourse, legitimize its decision to build a fence and attack Civic Platform for criticizing this idea when it was in opposition.

The political communication of Confederation

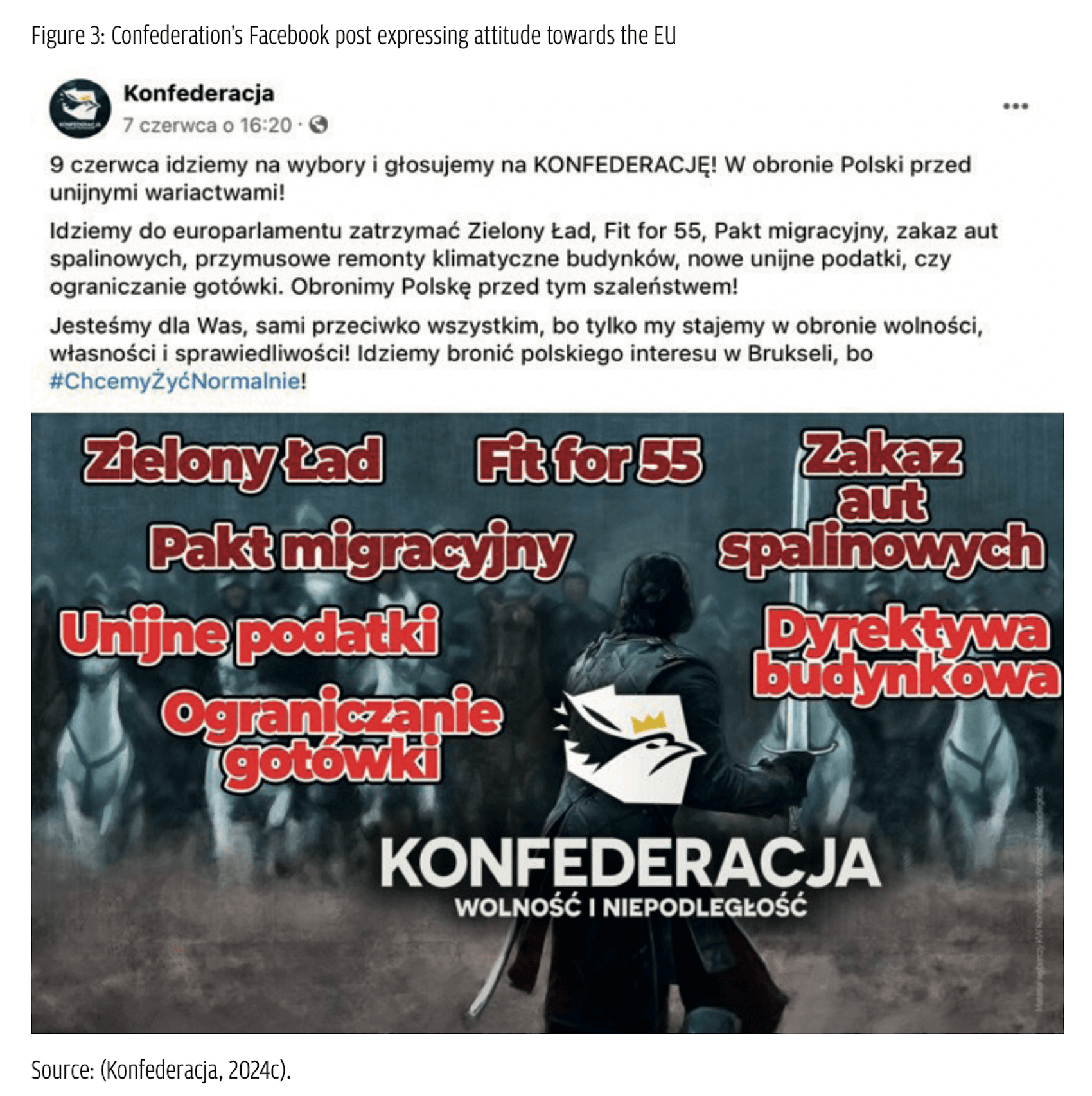

The electoral agenda of Confederation is best captured by the Facebook message posted two days before the elections, which deploys the visual metaphor of war to portray the relationship between the grouping and the EU and its policies (see Figure 3). The list of the issues mentioned in the picture to be fought with includes the European Green Deal, Fit for 55 (the EU’s plan to reduce carbon emissions), the Pact for Migration, banning combustion engine cars, European taxes, restricting the use of cash, and the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive.

The post neatly captures the Eurorejectionist attitude towards the EU, which is represented as a structure inimical to the national interests and the interests of ordinary Poles. Similarly to PiS, the main focus of attention was the European Green Deal, conceived as a prominent example of the madness of the EU elites driven by the socialist inclination to overregulate and the ideology of ‘climatism’. The EU is a bureaucratic structure with the tendency to go beyond its legal treaty limitations and is conceived as detached from normal people. As the grouping claimed, ‘We are going to the Europarliament to stop these absurd and harmful crazies coming from Brussels, because #WeWantToLiveNormally!’ (Konfederacja, 2024a).

The essence of the grouping’s stance is neatly captured by one of its leaders, Krzysztof Bosak: “I don’t know if you’ve noticed the new platitude promoted by the Eurofederalist lobby in Poland: they call the principle of unanimity in the EU by the term ‘liberum veto’ and suggest that it is some kind of systemic gangrene. Thus, they admit that it is the EU and not Poland that is the new state reference point for them. It’s power and decisiveness they care about. What they don’t add is that the more prerogatives in Brussels, the less in Warsaw. This is a zero-sum game. The sovereignty being shifted to Brussels, Strasbourg and Luxembourg is being lost in Poland. Our influence on the vector of the evolution of EU policies oscillates around zero, and the veto is the last hard tool that can influence anything in this organization. Instead of further strengthening the Eurocracy, we need to regain control!” (Konfederacja, 2024b).

Such a vision of European relations underpins the radically anti-establishment discourse of the Confederation, which allows the presentation of all the political elites as traitors of the Polish national interests. Contrary to the PO, which was conceived as representative of the interests of Germany, PiS’s agenda was attacked for its hypocrisy or for stealing programmatic ideas from the Confederation.

The EU environmental policy solutions were attacked for detrimental effects on the development of the economies of EU member states and led to the drastic deterioration of the standards of living for ordinary Poles: “The entire policy of the European Union will lead to the poor becoming even poorer, and the process of weakening nation-states will gain even more momentum! That’s why I’m going to the European Parliament to stop this madness and stand up for the interests of ordinary citizens!” (Zajączkowska, 2024).

Populist strategies were used to articulate other ideological themes. In line with the libertarian currents of the Confederation’s profile, the EU policies were also framed as illegitimate, ideological interference in ordinary people’s lives. According to the Confederation, poor people will be forced, for example, to conduct costly renovations of their houses to fulfil energy standards of the EU’s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive.

Another key issue on the campaign agenda was the rejection of the EU Pact on Migration. Confederation did not shy away from using racist and Islamophobic rhetoric, portraying migrants as a dangerous threat to security, demographics and culture and as a burden on welfare systems. They not only supported strengthening existing borders but also advocated for amending laws to permit more liberal use of firearms against migrants. Although less prominent, they also criticized the so-called ‘privileges’ granted to Ukrainian refugees, portraying them as undeserving. Additionally, Confederation leveraged the incidents at the Polish–Belarusian border to promote its hardline stance on migration.

The resonance of the campaign issues and the electoral support

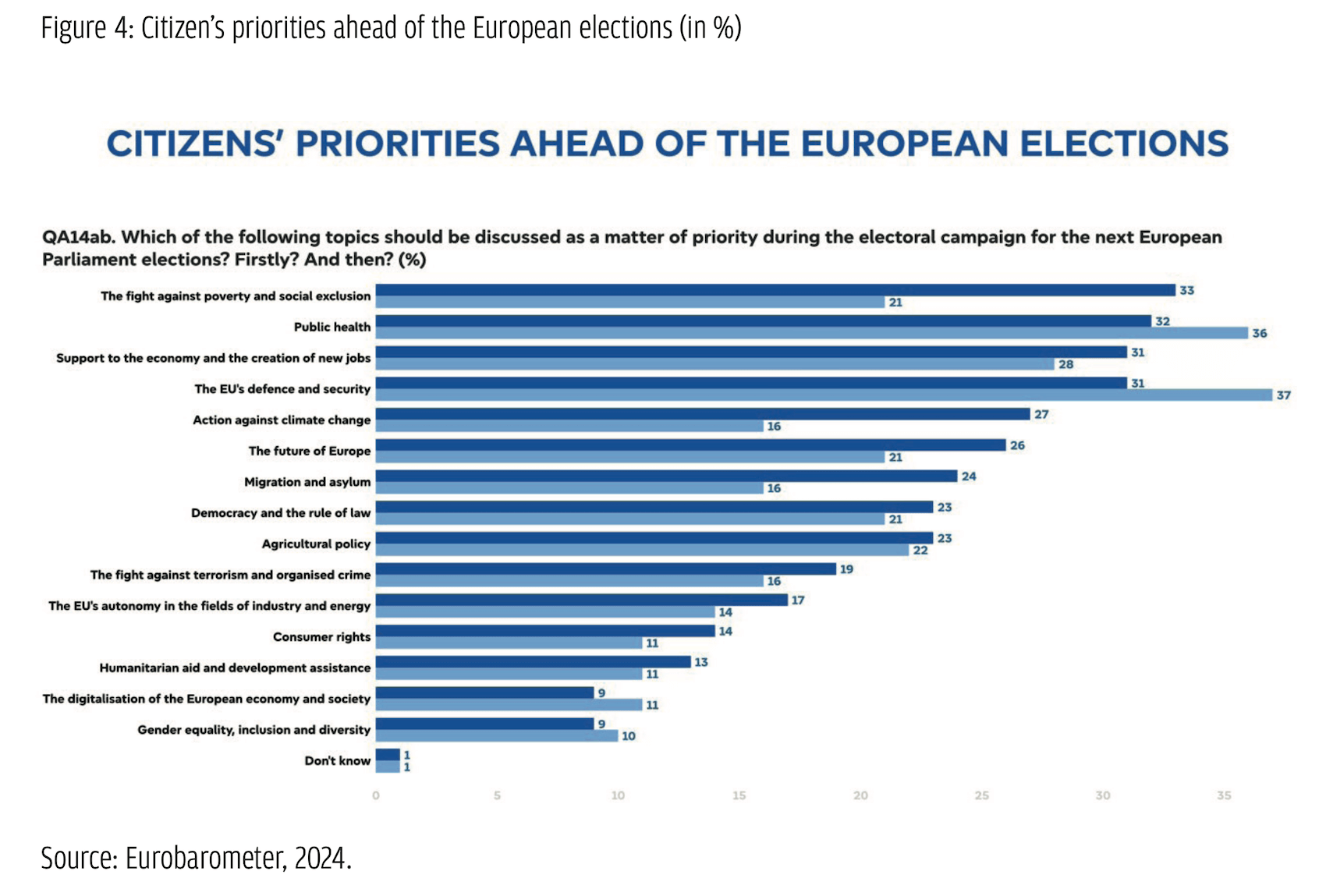

The results of the European Parliament’s Spring 2024 Eurobarometer sheds some light on the list of campaign topics of particular significance to Polish voters. According to the survey, the EU’s defence and security policy and public health ranked highest, 37% and 36%, respectively, among Polish voters. Support for the economy and creating new jobs (28%) and agricultural policy (22%) are of secondary interest. There is also a potential disconnect between the migration issue, one of the most potent topics for the political communication of the right-wing populists, and the interests of the voters. As the survey shows, migration and asylum scored only 16% despite extreme politicization of the issue and extensive media coverage, particularly just before the elections when the incidents on the Polish–Belarusian border took place. The timing of the survey might provide some explanation; in Poland, it took place in February, long before the campaign started. Second, the migration issue was embedded in the larger security narrative, a topic the voters recognized as the most important one. Interestingly, support for the actions against climate policy ranked at 16%, whereas at the EU level, the score was at 27%, which might explain why populist actors paid so much attention to the rejection of the European Green Deal and the Fit for 55 package.

The elections confirmed the structure of support for the right-wing populist electorate. First, PiS confirmed its support in rural areas (46.36% of voters) than in cities (30.67% of voters), among the elderly (only 16.2% of votes of those aged 29 and over and 46.1% of those over 60) and among less educated voters (TVN24, 2024). The Confederation was different, with as many as 30.1% voting for the group in the 18–29 age bracket. The breakdown by gender was also important: 16.5% of male eligible voters and 8.1% of female voters voted for the Confederation (very significantly, in this case, 0.3% more than for the Left). It is also worth noting the high loyalty of the PiS electorate, with only 8% of its 2023 voters supporting other groups. In the case of the Confederation, it was 16% (Katkowski, 2024). Interestingly, Confederation gained the support of the 165,000 PiS supporters (Machowski, 2024). Finally, the electoral turnout was significantly lower than during previous national elections (40.65% to 74.38%) but still relatively high if compared to the elections before 2023.

Conclusions

Although the elections confirmed the strength of polarization and the importance of the PO and PiS divide, with the two largest parties winning a combined 73.22% of the electoral vote, this did not prevent the Confederation from gaining an important third place in the electoral competition. Discursive structures of opportunity related to the dramatic situation in the east resonated with the Confederation’s securitized, anti-immigrant message. Moreover, as the oppositional actor, the grouping has greater credibility in proclaiming radical slogans than PiS, who previously held power.

Second, it appears that both parties will seek to slow down (PiS) or undermine (Confederation) the process of European integration and use the issues of immigration and environmental EU policies as important parts of the Eurosceptic agenda. Yet during the campaign, The Confederation announced that it would seek to establish a special commission in the European Parliament to investigate illegal immigration.

Third, the division on the right side of the political scene and the competition over the conservative electorate is also reflected at the European level as two actors joined different political groups in the European Parliament. Being part of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group, PiS was courted by Viktor Orbán to join his new alliance called Patriots for Europe (PfE). Initially, it seemed a very probable option for PiS if one takes public declarations of its politicians at face value.

Yet at the end of June, former Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki suggested in an interview with Politico that the option of joining Viktor Orbán was 50/50. As he declared, ‘It’s quite obvious that we could be united on a geographical platform and not [an] ideological platform. I’m less and less interested in all those ideological elements of the jigsaw’ (cited in Wax, 2024). Nevertheless, it turned out it was part of the protracted negotiation strategy over the distribution of the posts in the group. Ultimately, the longstanding relations between PiS and Fidesz were not translated into an alliance with the party, which adopts an entirely different stance on Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, the effectiveness of sanctions and the significance and scale of assistance for Ukraine. On 3 July 2024, it was announced that PiS would remain within ECR and renew its alliance with Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia.

The decision of which EP group to join was equally difficult for the Confederation, leading finally to internal divisions within the grouping. Only three out of six of the Confederation MEPs decided to join the Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) group led by the pro-Russian Alternative for Germany (AfD). Stanisław Tyszka, one of the MEPs who joined the group, admitted the differences but also listed commonalities: ‘opposing the EU’s crazy climate policy, the immigration policy that threatens the stability of our countries and Europe, and attempts to build a European superstate’ (Tyszka, 2024). Interestingly, all three politicians come from Sławomir Mentzen’s New Hope, one of the groups that form part of the Confederation alliance. Two other MEPs from the National Movement (Ruch Narodowy) refused to join the group and started negotiations with PfE.

(*) Artur Lipiński is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Journalism, at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland. He has participated in several international and Polish research projects and networks related to the representation of migrants in discourse (MEDIVA) and populist political communication (COST Action). From 2019 to 2022, he was a leader of the Polish team within DEMOS ‘Democratic Efficacy and the Varieties of Populism in Europe’, a collaborative H2020 Research & Innovation project. Currently, he is the leader of the Polish team within the Horizon Europe project MORES ‘Moral emotions. How they unite, how they divide.’ His research interests are focused on political communication and Polish right-wing politics. He has published on the uses of the historical past in political discourse in Poland and populist and right-wing political communication in Problems of Post-Communism, American Behavioral Scientist and the Journal of Contemporary European Studies.

References

Aja/X (2024). Beata Szydło w imieniu kandydatów PiS do PE podpisała przedwyborczą deklarację. “Chcemy żyć i oddychać po polsku w normalnym kraju.” https://wpolityce.pl/polityka/689998-jest-deklaracja-kandydatow-pis-do-pe-podpisala-ja-b-szydlo

Baszczak, Ł., Wincewicz, A., Zyzik, R. (2023). Poles and Ukrainians – the challenges of integrating refugees. Polish Economic Institute, Warsaw.

Bill, S. (2022). Counter-Elite populism and civil society in Poland: PiS’s strategies of elite replacement. East European Politics and Societies And Cultures. 36(1), 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0888325420950800

Konfederacja. (2024a, 3 May). Idziemy do europarlamentu, żeby zatrzymać te absurdalne i szkodliwe wariactwa płynące z Brukseli, bo #ChcemyŻyćNormalnie! [Video attached] Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=644736061171708

Konfederacja. (2024b, 9 May). Krzysztof Bosak: Nie wiem czy zauważyliście nowy frazes lansowany przez nadwiślańskie lobby eurofederalistów: nazywają zasadę jednomyślności w UE terminem „liberum veto”. [Image attached] Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/KONFEDERACJA2019/posts/pfbid02ULP6XKC6M77zoGs53ap4XnpJaNCQLMoPbkSFAF7o7EHoapjGzhm8qmqEoLeAaY2cl

Konfederacja. (2024c, 7 June). 9 czerwca idziemy na wybory i głosujemy na KONFEDERACJĘ! W obronie Polski przed unijnymi wariactwami! Idziemy do europarlamentu zatrzymać Zielony Ład, Fit for 55, Pakt migracyjny. [Image attached] Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/KONFEDERACJA2019/posts/pfbid02rMbNzHBFnrXHh6yibZJDzEagTtcT6XH2MRYPEbyc7GoJQYuhywcfFaewHzZBBYYnl

Duszczyk, M., Górny, A., Kaczmarczyk, P., & Kubisiak, A. (2023). War refugees from Ukraine in Poland–one year after the Russian aggression. Socioeconomic consequences and challenges. Regional Science Policy & Practice. 15(1), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12642

Eurobarometer (2024). EP Spring 2024 Survey: Use your vote–Countdown to the European elections. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3272

Kaczyński, J. (2024). Biało-Czerwoni! Europejska, Programowa Konwencja Prawa i Sprawiedliwości. https://pis.org.pl/aktualnosci/bialo-czerwoni-europejska-programowa-konwencja-prawa-i-sprawiedliwosci

Katkowski, K. (2024). Wyniki wyborów europejskich: gniew wymierzony w państwo. Fundacja Batorego. https://www.batory.org.pl/blog_wpis/wyniki-wyborow-europejskich-gniew-wymierzony-w-panstwo/

Krzyżanowska, N., & Krzyżanowski, M. (2018). ‘Crisis’ and Migration in Poland: Discursive Shifts, Anti-Pluralism and the Politicisation of Exclusion. Sociology 52(3), 612–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518757952

Krzyżanowski, M. (2020). Discursive shifts and the normalisation of racism: imaginaries of immigration, moral panics and the discourse of contemporary right-wing populism. Social Semiotics, 30(4), 503–527. DOI: 10.1080/10350330.2020.1766199

Machowski, Z. (2024). Wybory do PE: zwycięstwo demokratów czy udana kontrofensywa prawicy? Gazeta Wyborcza. https://wyborcza.pl/7,75968,31068665,wybory-do-pe-zwyciestwo-demokratow-czy-udana-kontrofensywa.html

Müller, J.-W. (2016). What is populism? University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

PiS. (2024a, 16 May). Dzisiaj sprawą, którą musimy brać pod uwagę, jest pakt migracyjny. Pakt, który został ostatecznie przyjęty. I to jest sprawa dla nas niezmiernie ważna. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/100044312205441/posts/1010670630420001

PiS. (2024b, 19 May). Lista nr 7 to 7 razy #TAKdlaPolski. [Image attached] Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/pisorgpl/posts/pfbid02HGfRASNPFJy1gmfw8xJpez41EQqaNByV9dqrJH6g4Z16aBveNJBEXDEAi51EcWnLl

PiS. (2024c, 19 May). #TAKdlaWolności #TAKdlaPolski (Image attached] Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/pisorgpl/posts/pfbid02TTVVK3gcvfEmxcFy69xXTo5FAhMiZFKWdYUDKB5ieTwKdL5iDVr7uHR7DjRPaZTNl

PiS. (2024d, 26 May). Te zbliżające się wybory do PE są niesłychanie ważne. Pierwsze półrocze rządów naszych politycznych przeciwników pokazało, że ten proces marszu Polski ku Europie. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/100044312205441/posts/1016762776477453

Rooduijn, M., Pirro A. L.P., Halikiopoulou D., Froio c., Van Kessel S., De Lange S., Mudde C., Taggart, P. (2023). The PopuList 3.0: An Overview of Populist, Far-left and Far-right Parties in Europe. www.popu-list.org. DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/2EWKQ

Sadura, P., Sierakowski, S. (2022). Polacy za Ukrainą, ale przeciw Ukraińcom. Raport z badań socjologicznych. Warszawa.

Sadurski, W. (2019). Poland’s constitutional breakdown. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Stanley B. (2023). Poland. In N. Ringe, L. Renno (Eds.). Populists and the pandemic: how populists around the world responded to COVID-19 (105–116). Routledge.

Szczerbiak, A. (2023). Why did the opposition win the Polish election? https://notesfrompoland.com/2023/10/31/why-did-the-opposition-win-the-polish-election/

Tak dla polskiego rolnictwa (2024). Retrieved 12 June 2024, from https://pis.org.pl/aktualnosci/tak-dla-polskiego-rolnictwa, accessed on 20.06.2024.

TVN24. (2024, 9 June). Wybory do Parlamentu Europejskiego 2024: Jak głosowali najmłodsi, jak najstarsi, jaki wynik Konfederacji? [2024 European Parliament elections: How did the youngest and oldest vote, and what was Confederation’s result?], TVN24, 9 June 2024, https://tvn24.pl/wybory-do-europarlamentu-2024/wybory-do-parlamentu-europejskiego-2024-jak-glosowali-najmlodsi-jak-najstarsi-jaki-wynik-konfederacji-st7955037

Tyszka, S. [@styszka] (2024, 10 July). Przed chwilą powołaliśmy zupełnie nową grupę polityczną w europarlamencie: Europę Suwerennych Narodów [Tweet]. Twitter. https://x.com/styszka/status/1811059236543123916?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1811059236543123916%7Ctwgr%5E362ff4a2b6f6d9632ddeded68943728ed9ca9555%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fnotesfrompoland.com%2F2024%2F07%2F10%2Fsplit-in-polish-far-right-confederation-as-half-its-meps-join-germanys-afd-in-new-eu-grouping%2F

Van Kessel, S. & Castelein, R. (2016). Shifting the blame. Populist politicians’ use ofTwitter as a tool of opposition. Journal of Contemporary European Research. 12(2), 594 –614. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v12i2.709

Wax E. (2024). Poland’s Law and Justice ‘50/50’ about leaving Giorgia Meloni and joining forces with Viktor Orbán, Politico. https://www.politico.eu/article/poland-law-and-justice-mateusz-morawiecki-giorgia-meloni-viktor-orban/

White-Red! European, Programmatic Convention of Law and Justice (2024). Retrieved June 15, 2024, from https://pis.org.pl/aktualnosci/bialo-czerwoni-europejska-programowa-konwencja-prawa-i-sprawiedliwosci, accessed on 20.06.2024.

Wyrwał, M., Żemła, E. (2024). Polscy żołnierze zakuci w kajdanki na granicy z Białorusią. W wojsku wrze. Onet. https://wiadomosci.onet.pl/tylko-w-onecie/polscy-zolnierze-zakuci-w-kajdanki-na-bialoruskiej-granicy-w-wojsku-wrze/kv2w39q

Zajączkowska, Ewa. (2024, May 12). To od Was zależy, czy 9 czerwca wybierzemy do Parlamentu Europejskiego reprezentację, która będzie dbała o polski interes, czy wybierzemy ludzi, którzy za pieniądze od unijnych [Image attached] Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/EwaZajaczkowskacom/posts/pfbid0ikPMMxb2SzsvAhDF6svi97WP4Mp8NPkXsAWxFAiQFVUw53nXmFx9puWmzq7v6GFTl

Within this period, Bulgaria had two short-lived regular governments. A new coalition government was formed in December after the November 2021 elections, under the premiership of Kiril Petkov, uniting the winner of the election PP (25.67%) with three coalition partners—BSP, ITN and the DB alliance. The government survived until June 2022, when it was removed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence initiated by GERB after ITN ended its support for the government and withdrew its members from ministerial posts. The Petkov government had the difficult task of dealing with the war in Ukraine, which erupted in February 2022 and divided public opinion in Bulgaria. With a large pro-Russian population, the war enabled parties like Vazrazhdane to thrive while constraining the government to maintain a delicate balance between the country’s commitment to its Euro-Atlantic partners and pressure from pro-Russian groups. Although Bulgaria enforced EU sanctions on Russia, phased out Russian oil deliveries, and provided military support for Ukraine, there has been continuous opposition from both inside and outside the National Assembly to these actions (Zankina, 2023).

Within this period, Bulgaria had two short-lived regular governments. A new coalition government was formed in December after the November 2021 elections, under the premiership of Kiril Petkov, uniting the winner of the election PP (25.67%) with three coalition partners—BSP, ITN and the DB alliance. The government survived until June 2022, when it was removed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence initiated by GERB after ITN ended its support for the government and withdrew its members from ministerial posts. The Petkov government had the difficult task of dealing with the war in Ukraine, which erupted in February 2022 and divided public opinion in Bulgaria. With a large pro-Russian population, the war enabled parties like Vazrazhdane to thrive while constraining the government to maintain a delicate balance between the country’s commitment to its Euro-Atlantic partners and pressure from pro-Russian groups. Although Bulgaria enforced EU sanctions on Russia, phased out Russian oil deliveries, and provided military support for Ukraine, there has been continuous opposition from both inside and outside the National Assembly to these actions (Zankina, 2023).

More importantly, the two-in-one elections significantly shifted the debate towards domestic issues. Opinion polls indicated corruption (59%), low income (57%), and healthcare (45%) to be the top three issues of voter concern (Alpha Research 2024a), while poverty and equality were singled out as the top priorities the EU should focus on (Trend 2024). Rising prices and increased cost of living (56%) along with the economic situation (53%) were the main motivators for Bulgarian voters – much more so than the EU average of 42% and 41%, respectively (Eurobarometer 2024).

More importantly, the two-in-one elections significantly shifted the debate towards domestic issues. Opinion polls indicated corruption (59%), low income (57%), and healthcare (45%) to be the top three issues of voter concern (Alpha Research 2024a), while poverty and equality were singled out as the top priorities the EU should focus on (Trend 2024). Rising prices and increased cost of living (56%) along with the economic situation (53%) were the main motivators for Bulgarian voters – much more so than the EU average of 42% and 41%, respectively (Eurobarometer 2024).  GERB convincingly won the 2024 European Parliament elections with 23.55% of the votes and five seats. Second came Dvizhenie za Prava i Svobodi (Movement for Rights and Freedoms, DPS) with 14.66% of the votes and three seats, closely followed by the PP–DB alliance, with 14.45% and the same number of seats, and Vazrazhdane (Revival) with 13.98% and also three seats. While pro-EU parties received the majority of the votes in the election, the results of Vazrazhdane and the increase of radical-right MEPs from 2 to 3 are a cause for great concern amidst an overall rise of the populist radical right in the European Parliament.

GERB convincingly won the 2024 European Parliament elections with 23.55% of the votes and five seats. Second came Dvizhenie za Prava i Svobodi (Movement for Rights and Freedoms, DPS) with 14.66% of the votes and three seats, closely followed by the PP–DB alliance, with 14.45% and the same number of seats, and Vazrazhdane (Revival) with 13.98% and also three seats. While pro-EU parties received the majority of the votes in the election, the results of Vazrazhdane and the increase of radical-right MEPs from 2 to 3 are a cause for great concern amidst an overall rise of the populist radical right in the European Parliament.

Among these parties, two are clear cases of populist radical parties based on the PopuList categorization

Among these parties, two are clear cases of populist radical parties based on the PopuList categorization

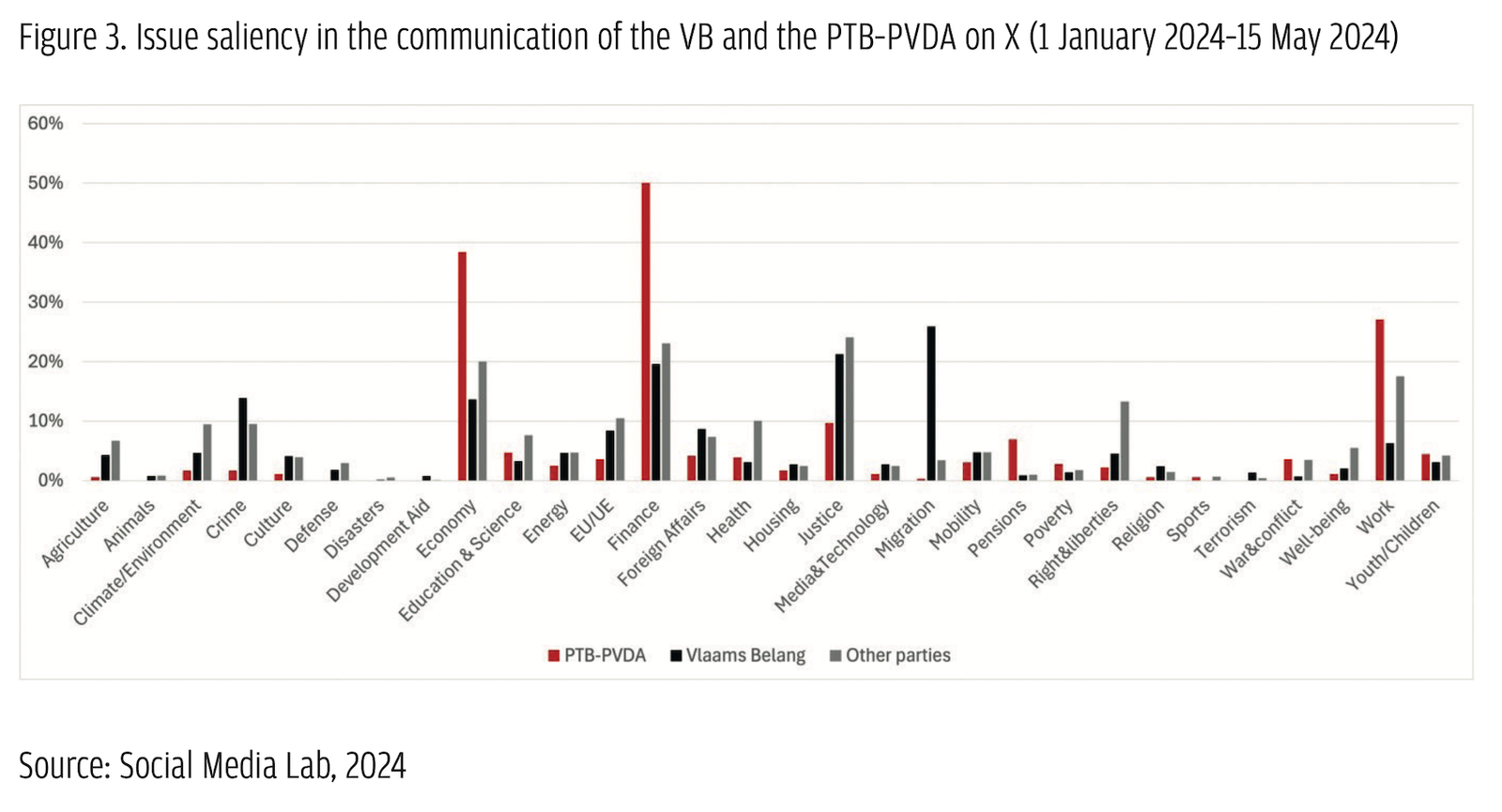

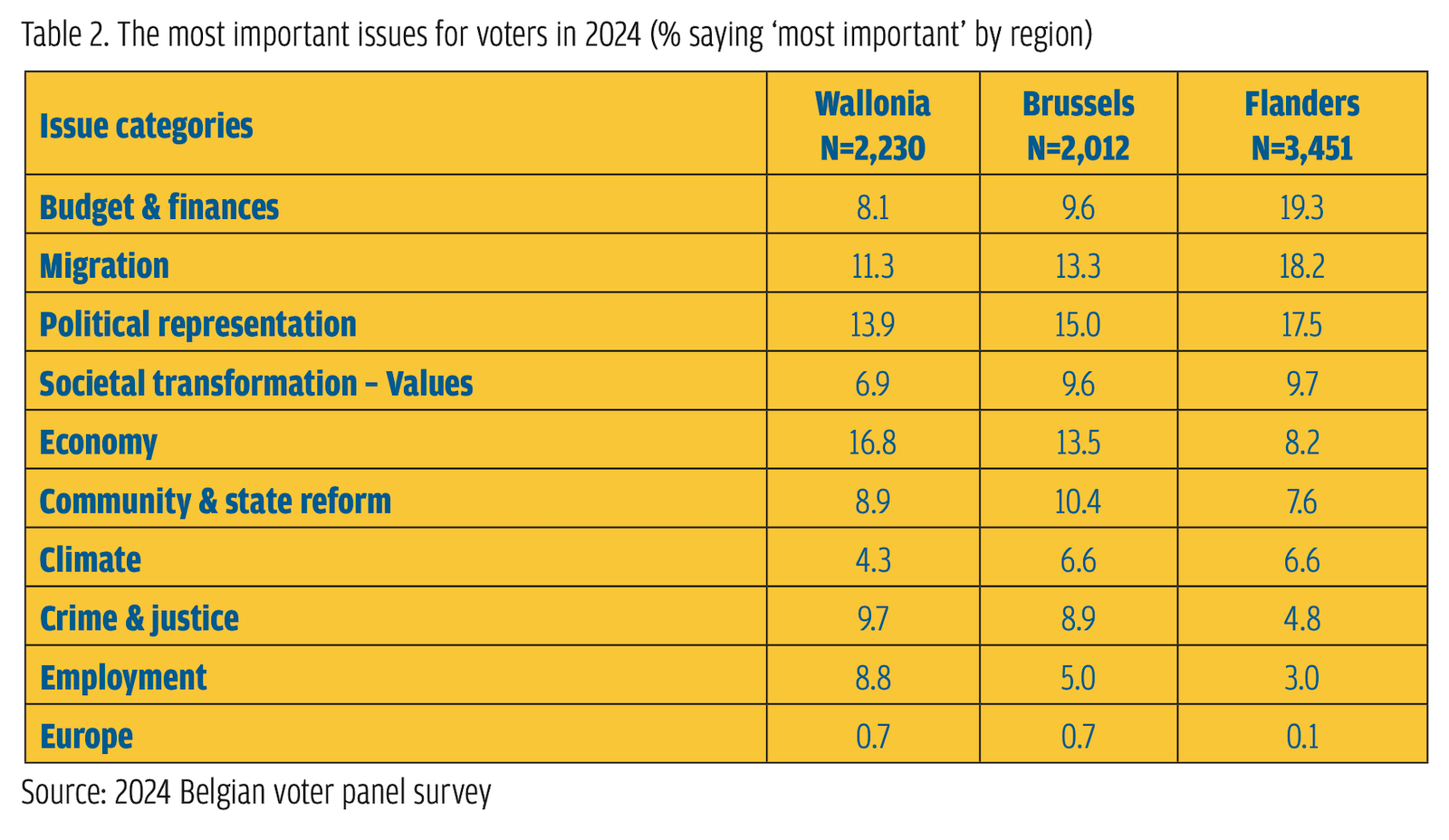

The profile of VB and PTB–PVDA voters in 2019 presented similarities. Data from the 2019 Belgian panel survey (Michel et al., 2024) show that both parties attracted a younger, more male voter group with lower levels of education and a protest component, and displaying lower levels of trust and satisfaction with the government, but also higher levels of anger (Gallina et al., 2020; Jacobs et al., 2024). Populist radical parties thus clearly capitalized on voters seeking an alternative. But they also attracted issue-based voting on their core respective issues (Goovaerts et al., 2020; Walgrave et al., 2020).

The profile of VB and PTB–PVDA voters in 2019 presented similarities. Data from the 2019 Belgian panel survey (Michel et al., 2024) show that both parties attracted a younger, more male voter group with lower levels of education and a protest component, and displaying lower levels of trust and satisfaction with the government, but also higher levels of anger (Gallina et al., 2020; Jacobs et al., 2024). Populist radical parties thus clearly capitalized on voters seeking an alternative. But they also attracted issue-based voting on their core respective issues (Goovaerts et al., 2020; Walgrave et al., 2020). While the content reveals the ideological focus of these parties, the tone of their communication connects to their populist core. Both parties heavily rely on attacks as a mode of communication. Previous studies have shown that personal or programmatic attacks represent 26.5% of the total communication of the VB on X (first party in Belgium) and 25% for the PTB–PVDA (Close et al., 2023).

While the content reveals the ideological focus of these parties, the tone of their communication connects to their populist core. Both parties heavily rely on attacks as a mode of communication. Previous studies have shown that personal or programmatic attacks represent 26.5% of the total communication of the VB on X (first party in Belgium) and 25% for the PTB–PVDA (Close et al., 2023).

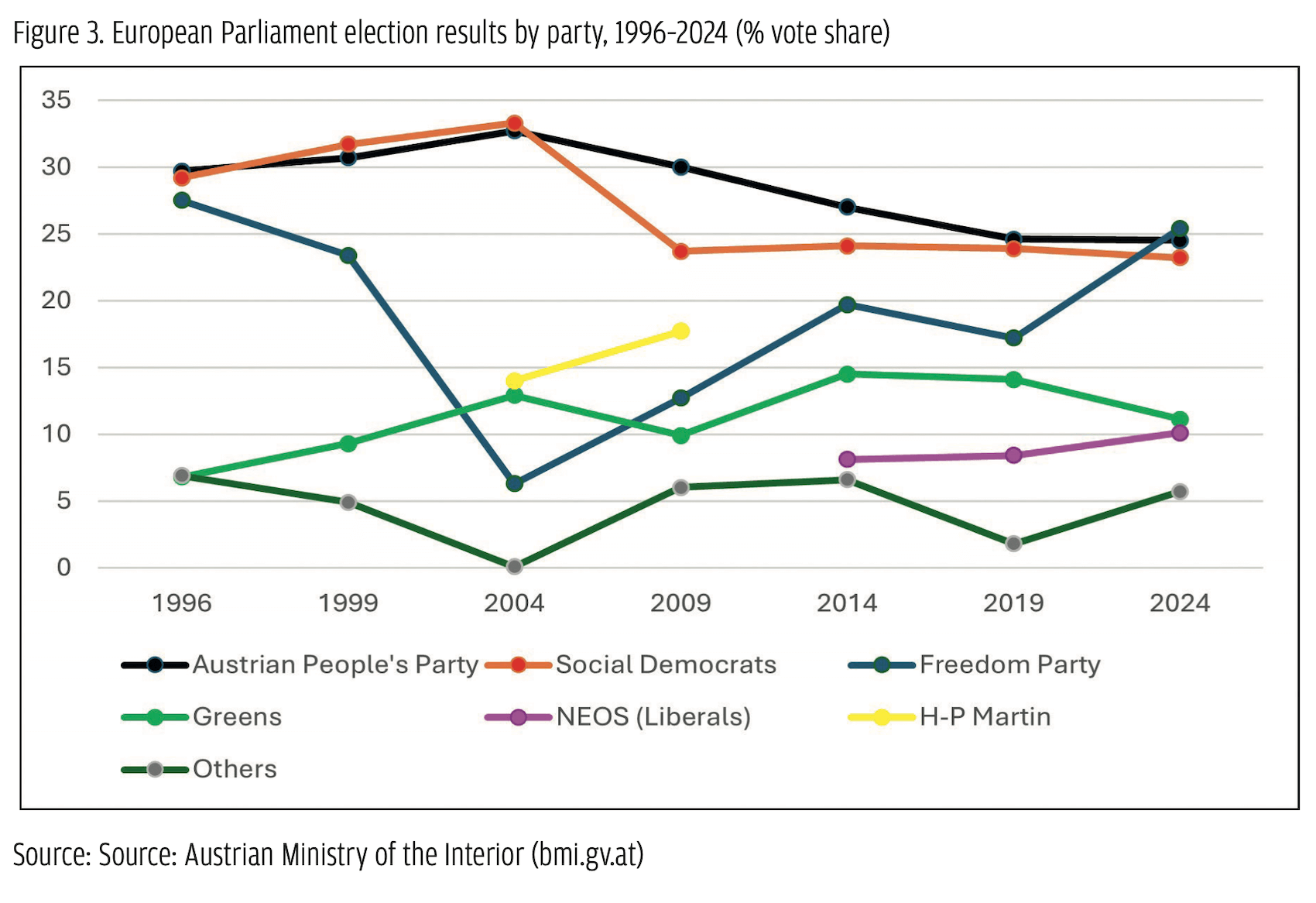

During the 2024 EU elections, the FPÖ was the only populist party represented in the Austrian parliament. The only other party that might be classified as populist that ran in the elections was the Democratic, Neutral, Authentic (DNA) list led by a former physician and anti-vaccine activist, who played an active role in protests directed against the protective measures taken by the Austrian government during the COVID-19 pandemic. This party, however, was founded just months before the elections, received hardly any media- and public attention, and failed to win a seat, taking just 2.7% of the votes. The following report will therefore restrict its focus to the FPÖ.

During the 2024 EU elections, the FPÖ was the only populist party represented in the Austrian parliament. The only other party that might be classified as populist that ran in the elections was the Democratic, Neutral, Authentic (DNA) list led by a former physician and anti-vaccine activist, who played an active role in protests directed against the protective measures taken by the Austrian government during the COVID-19 pandemic. This party, however, was founded just months before the elections, received hardly any media- and public attention, and failed to win a seat, taking just 2.7% of the votes. The following report will therefore restrict its focus to the FPÖ. The demand side of the EU: Critical populism in Austria

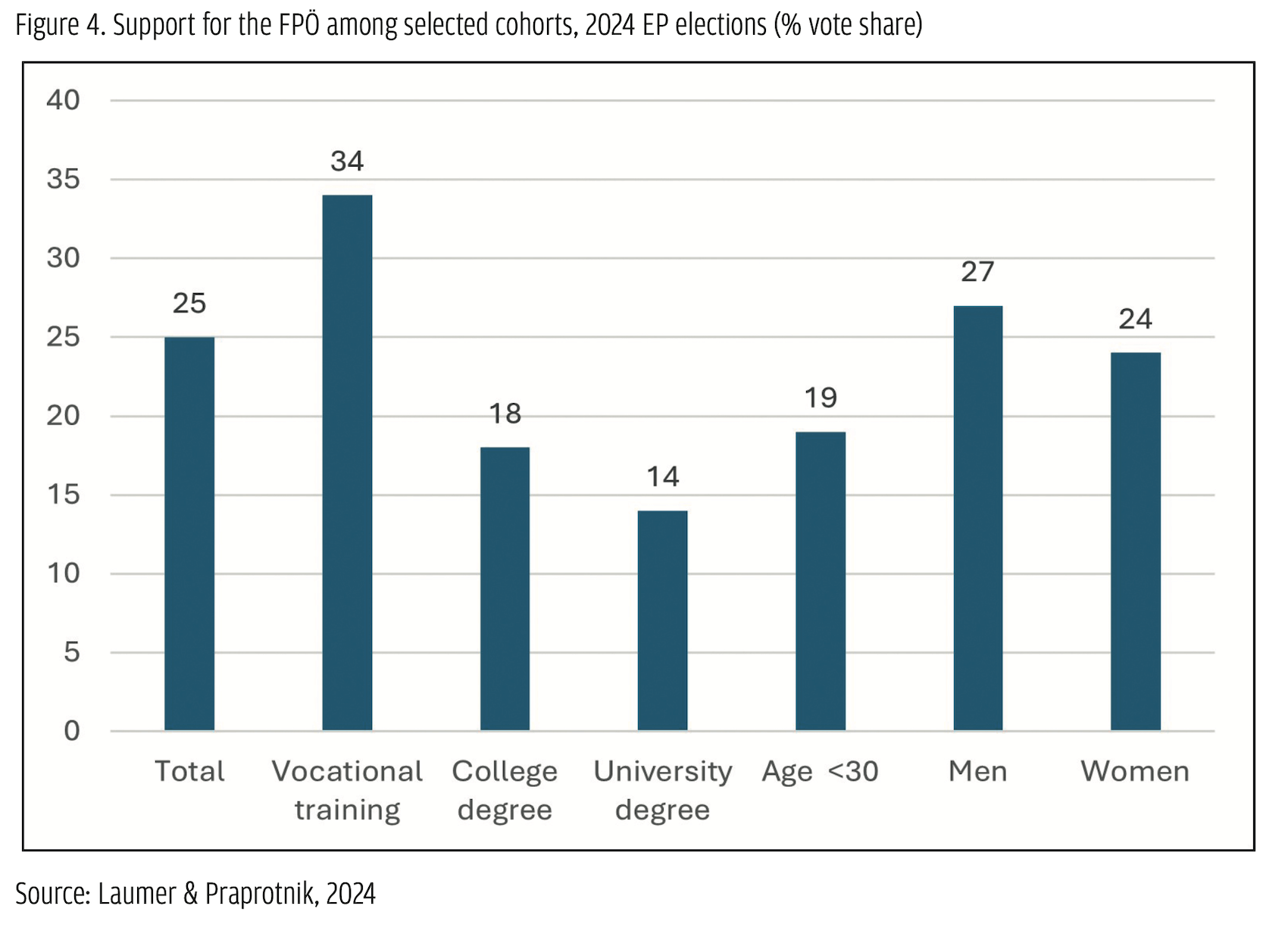

The demand side of the EU: Critical populism in Austria Looking at sociodemographic characteristics (Figure 3), the FPÖ somewhat underperformed amongst voters below the age of 30. Regarding education, it was most successful amongst voters who had completed vocational training and least successful amongst high-school and university graduates. Interestingly, and in line with preceding regional elections (Salzburger Nachrichten, 2024), the once significant gender gap has shrunk considerably compared to the elections in 2019. While back then, 26% of men but only 10% of women voted for the FPÖ, this time it was 27% of men compared to 24% of women. Amongst voters holding at least a college degree, the gap even vanished entirely, with 16% of men and 17% of women opting for the FPÖ (Laumer & Praprotnik, 2024). Amongst others, these changes may be a consequence of the position the party took during the COVID-19 pandemic (especially its critique to discriminate restrictions between vaccinated and non-vaccinated citizens) – which was also found among many (also highly-educated) women (Die Presse, 2021).

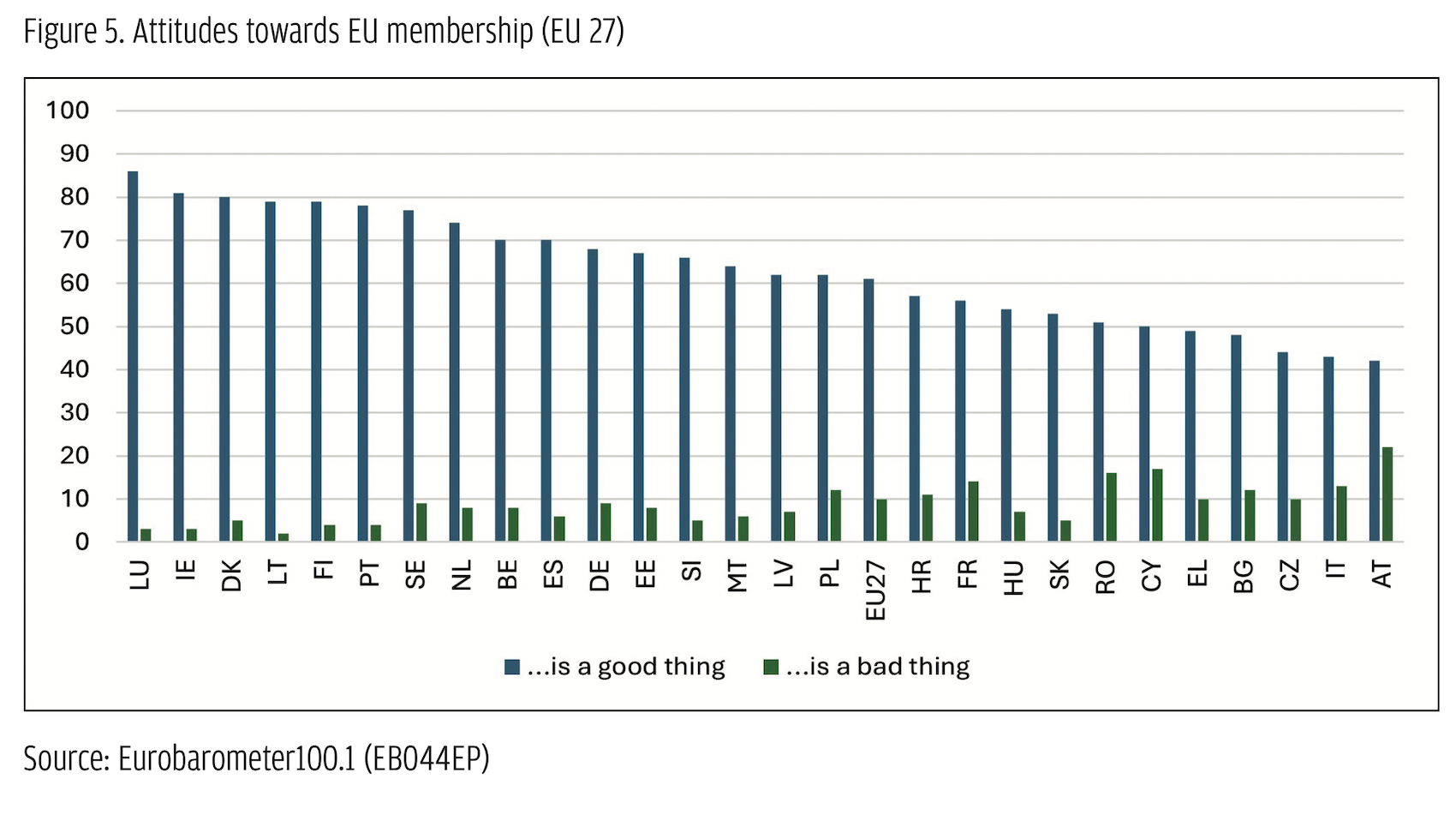

Looking at sociodemographic characteristics (Figure 3), the FPÖ somewhat underperformed amongst voters below the age of 30. Regarding education, it was most successful amongst voters who had completed vocational training and least successful amongst high-school and university graduates. Interestingly, and in line with preceding regional elections (Salzburger Nachrichten, 2024), the once significant gender gap has shrunk considerably compared to the elections in 2019. While back then, 26% of men but only 10% of women voted for the FPÖ, this time it was 27% of men compared to 24% of women. Amongst voters holding at least a college degree, the gap even vanished entirely, with 16% of men and 17% of women opting for the FPÖ (Laumer & Praprotnik, 2024). Amongst others, these changes may be a consequence of the position the party took during the COVID-19 pandemic (especially its critique to discriminate restrictions between vaccinated and non-vaccinated citizens) – which was also found among many (also highly-educated) women (Die Presse, 2021). Looking at voters’ issue preferences shows that, generally, there is quite a significant demand for EU-critical positions within the Austrian electorate. While in the 1994 constitutional referendum on the country’s EU accession, a two-thirds majority voted ‘yes’, approval rates started to drop soon thereafter, and Austrian citizens have ranked amongst the most critical ones across the EU ever since (Fallend, 2008). As Figure 5 shows, in the Eurobarometer from autumn 2023 (European Parliament, 2023), Austria not only recorded the highest share of citizens seeing EU membership as a ‘bad thing’ (22%) but also the lowest share of those seeing it as a ‘good thing’ (42%).

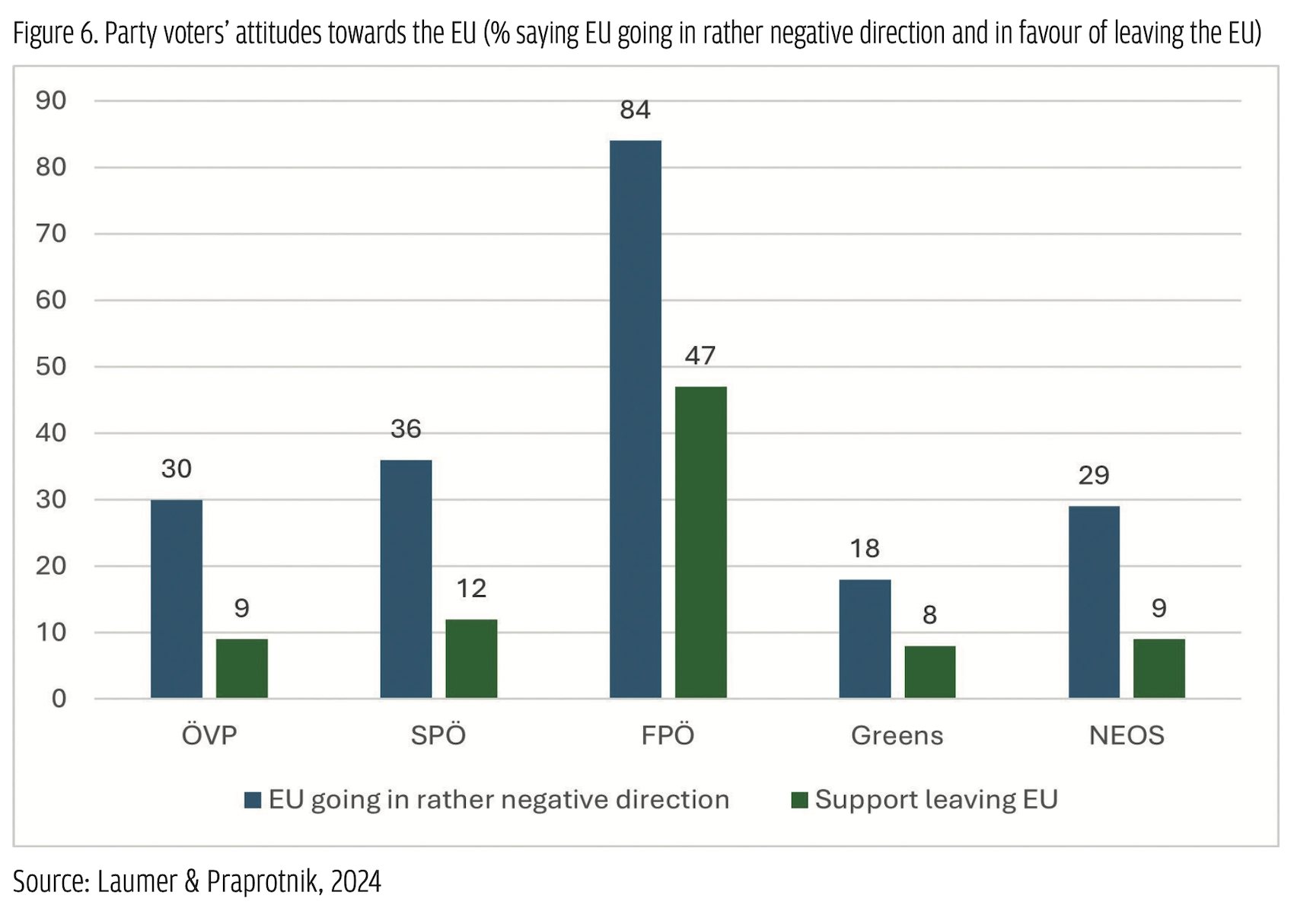

Looking at voters’ issue preferences shows that, generally, there is quite a significant demand for EU-critical positions within the Austrian electorate. While in the 1994 constitutional referendum on the country’s EU accession, a two-thirds majority voted ‘yes’, approval rates started to drop soon thereafter, and Austrian citizens have ranked amongst the most critical ones across the EU ever since (Fallend, 2008). As Figure 5 shows, in the Eurobarometer from autumn 2023 (European Parliament, 2023), Austria not only recorded the highest share of citizens seeing EU membership as a ‘bad thing’ (22%) but also the lowest share of those seeing it as a ‘good thing’ (42%).  The FPÖ was very successful in attracting these groups. According to exit polls, 84% of its voters see the EU taking a rather negative development and 63% would even support Austria leaving the EU (Figure 6).

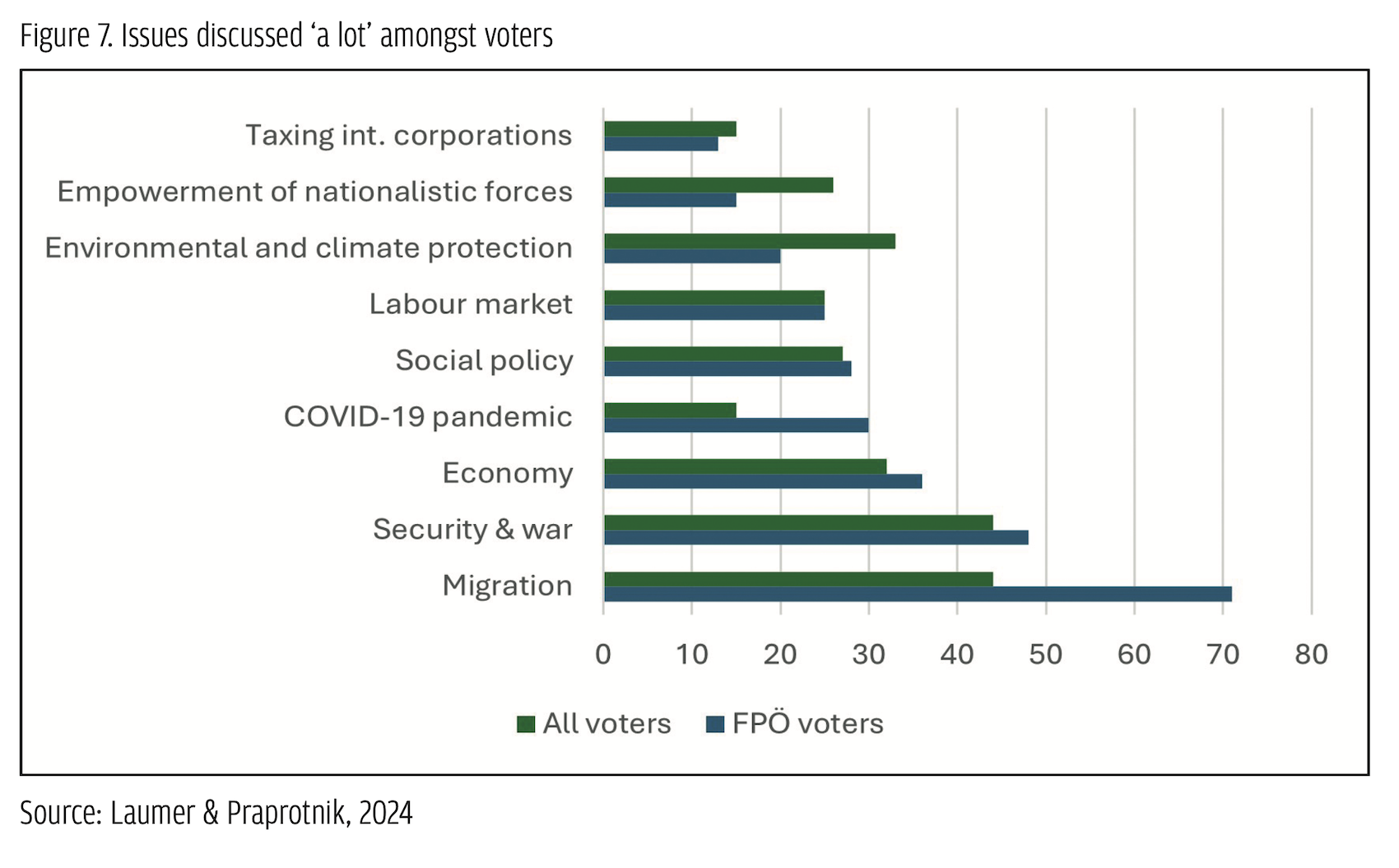

The FPÖ was very successful in attracting these groups. According to exit polls, 84% of its voters see the EU taking a rather negative development and 63% would even support Austria leaving the EU (Figure 6). Overall, however, only 4% stated that EU protest was their main reason to vote for the FPÖ, while 40% pointed to the party’s issue positions more generally. Looking at these issues, again, reveals a considerable overlap with the issues the party pushed in its campaign. Among the issues FPÖ voters discussed ‘a lot’ before the elections, ‘migration’ clearly ranks highest (71%), followed by ‘security and war’ (48%), the ‘economy’ (36%), and the ‘Covid pandemic’ (30%), with ‘environment and climate protection’ clearly lagging behind (20%).

Overall, however, only 4% stated that EU protest was their main reason to vote for the FPÖ, while 40% pointed to the party’s issue positions more generally. Looking at these issues, again, reveals a considerable overlap with the issues the party pushed in its campaign. Among the issues FPÖ voters discussed ‘a lot’ before the elections, ‘migration’ clearly ranks highest (71%), followed by ‘security and war’ (48%), the ‘economy’ (36%), and the ‘Covid pandemic’ (30%), with ‘environment and climate protection’ clearly lagging behind (20%). Public attention for the elections overall was relatively modest. About eight weeks before the elections, less than 50% of the Austrian electorate reported knowing the parties’ lead candidates, and even more stated that they could not assess their work (Die Presse, 2024). To the extent that the election was an issue, however, the FPÖ and its core issues featured quite prominently in the debates. In the three TV debates that featured all lead candidates, migration and the war between Russia and Ukraine were discussed for the longest time (followed by the climate crisis). Given the singularity of its positions, the FPÖ was criticized by all other parties quite harshly in all these debates. This criticism resulted in the FPÖ receiving by far the most attention and also allowed the party to (once again) present itself as the only ‘real’ alternative vis-à-vis a purported Einheitspartei (‘single political party’), composed of the ÖVP, the Social Democrats (SPÖ), the Greens and the Liberals. A similar phenomenon can be observed regarding general news coverage where, for example, the election poster discussed above met with extensive criticism by journalists both nationally and internationally, pushing attention to the FPÖ itself and its political demands even further (Hammerl, 2024).

Public attention for the elections overall was relatively modest. About eight weeks before the elections, less than 50% of the Austrian electorate reported knowing the parties’ lead candidates, and even more stated that they could not assess their work (Die Presse, 2024). To the extent that the election was an issue, however, the FPÖ and its core issues featured quite prominently in the debates. In the three TV debates that featured all lead candidates, migration and the war between Russia and Ukraine were discussed for the longest time (followed by the climate crisis). Given the singularity of its positions, the FPÖ was criticized by all other parties quite harshly in all these debates. This criticism resulted in the FPÖ receiving by far the most attention and also allowed the party to (once again) present itself as the only ‘real’ alternative vis-à-vis a purported Einheitspartei (‘single political party’), composed of the ÖVP, the Social Democrats (SPÖ), the Greens and the Liberals. A similar phenomenon can be observed regarding general news coverage where, for example, the election poster discussed above met with extensive criticism by journalists both nationally and internationally, pushing attention to the FPÖ itself and its political demands even further (Hammerl, 2024).