Please cite as:

Kenes, Bulent & Yilmaz, Ihsan.(2024). “Digital Authoritarianism and Religious Populism in Turkey.”

Populism & Politics (P&P). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). September 14, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0042

Abstract

This article explores the interplay between religious populism, religious justification and the systematic attempts to control cyberspace by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey. Drawing from an array of scholarly sources, media reports, and legislative developments, the study unravels the multifaceted strategies employed by the ruling AKP to monopolize digital media spaces and control the information published, consumed and shared within these spaces. The narrative navigates the evolution of the AKP’s tactics, spotlighting the fusion of religious discourse with state policies to legitimize stringent control mechanisms within the digital sphere. Emphasizing the entwinement of Islamist populism with digital authoritarianism, the article provides evidence of the strategic utilization of religious platforms, figures, and media outlets to reinforce the narrative of digital authoritarianism as a protector of Islamic values and societal morality. Key focal points include the instrumentalization of state-controlled mosques and religious institutions to propagate government narratives on digital media censorship, alongside the co-option of religious leaders to endorse control policies. The article traces the rise of pro-AKP media entities and the coercive tactics used to stifle dissent, culminating in the domination of digital spaces by government-aligned voices. Furthermore, the analysis elucidates recent legislative endeavors aimed at further tightening the government’s grip on social media platforms, exploring the potential implications for free speech and democratic discourse in the digital realm.

Keywords: Digital Authoritarianism, Religious Populism, Media Control, Islamism, Digital Governance, Cyberspace, Fatwas, Sermons

By Bulent Kenes & Ihsan Yilmaz

Introduction

The rise of religious populism and authoritarianism marks Turkey’s political trajectory under Erdoganism, in which the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has transformed the nation’s governance since 2002. The aftermath of Kemalism brought with it a paradoxical quest for modernization within a less-than-democratic framework. The AKP’s ascent heralded a shift, initially portraying pro-democratic sentiments, but is now defined by authoritarian leanings akin to those of the Kemalist regime. This metamorphosis mirrors global trends that have witnessed authoritarian governance seeping into democratic systems.

The distinctiveness of Erdoganism lies in its merging of Islamist populism into Turkey’s political fabric, fostering electoral authoritarianism, neopatrimonialism, and populism. AKP leader and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s centralized authority converges the Turkish state, society, and governmental institutions, perpetuating a widespread sense of uncertainty, fear, and trust in a strong leader that bolsters authoritarianism. The dynamics of religion, state, and identity construction redefine Turkey’s sociopolitical landscape, with governmental activities aimed at constructing a ‘pious generation’ while diminishing voices of dissent (Yabanci, 2019).

The political landscape in Turkey, particularly under the rule of the AKP, has witnessed a discernible shift marked by increasingly stringent measures against various segments of society. This trend notably encompasses a wide spectrum of individuals, including political opposition factions, minority groups, human rights advocates, academics, journalists, and dissenting voices within civil society (Westendarp, 2021; BBC News, 2020; BBC News, 2017a; Homberg et al., 2017).

Statistics paint a stark picture of the government’s crackdown: alarmingly, more than 150 thousand individuals have faced dismissals from their positions, while over 2 million people have become subjects of “terrorism investigations” following a coup attempt in the country in 2016 (Turkish Minute, 2022). Furthermore, approximately 100 thousand arrests have been documented since the onset of these measures in 2016. The widespread erasure of oppositional or critical voices – real or potential – extends beyond the targeting of individuals and encompasses entire institutions. Academic institutions have borne the brunt of this oppressive regime, resulting in the closure of more than 3 thousand educational establishments, and the dismissal of 6 thousand scholars. The media sector has also suffered a significant blow, with 319 journalists arrested and 189 media outlets forcefully shut down, signaling a profound attack on free speech and the press. The legal profession has also faced targeting, witnessing the loss of 4 and a half thousand legal professionals (Turkey Purge 2019).

Moreover, the AKP’s influence has transcended national borders, impacting Turkish citizens living in diasporas around the world. Instances of extradition of members of the Turkish diaspora on charges related to terrorism or alleged connections to security threats have been reported, highlighting the government’s efforts to exert control beyond its territorial boundaries. This phenomenon has led to the perception of the government as possessing “long arms,” capable of reaching, influencing, and punishing individuals even when living outside the country (Edwards, 2018).

The evolution of Turkey’s digital landscape since 2016 reveals a pronounced shift marked by intensified security protocols and offline repressions. A critical assessment conducted by Freedom House, evaluating global internet freedom between 2016 and 2020, highlights a concerning and tangible decline in internet freedom in Turkey, which significantly intensified following the failed coup attempt in 2016. Notably, the classification of internet freedom as being “not free” underscores the severity of limitations imposed during these years (Daily Sabah, 2021a, 2021b; World Bank, 2021).

Pervasive Online Presence of Turkish Citizens

Despite this lack of freedom, statistics highlight the pervasive influence of the internet within Turkish society (World Bank, 2021). A study from the initial quarter of 2021 indicated that over 80 percent of internet users were consistently active online during these three months, highlighting the integral role the internet plays in the lives of citizens (Daily Sabah, 2021). Data reports tracking internet usage of Turkish citizens suggest that in early 2024, internet penetration in Turkey was at its highest level at 86.5 percent (Kemp, 2024). These findings demonstrate a picture of sustained and pervasive digital engagement within the populace.

Social media findings further underscore the influence of internet usage, revealing an average daily duration of 7 hours and 29 minutes per individual (Bianet, 2020). By January 2024, the number of social media users in the country stands at 57.5 million users, or nearly 70 percent of the total population (Kemp, 2024). Social media platforms, including Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, and Twitter, account for this considerable online presence (Bianet 2020).

Crucially for this discussion, this digital landscape has become a vital arena for dissenting voices, particularly as traditional media outlets witness declining audience numbers.

Consequently, the internet has emerged as a potent tool for voices of opposition within Turkey. In response to the increased possibilities for these voices in an increasingly online society, the AKP government has initiated various regulatory and surveillance measures aimed at controlling and monitoring the digital sphere, reflecting efforts to suppress dissenting narratives and oppositional voices (Bellut, 2021). Their efforts at digital governance reflect and intensify the government’s broader strategy of curtailing dissent across various levels of society.

The AKP’s Use of Religion to Legitimize a Digital Authoritarian Agenda

The intertwining of religion and state under the AKP’s governance has legitimized and fortified its digital authoritarianism. For example, a recent trend reveals the government’s adept use of Islamic discourse to rationalize the imposition of censorship and crackdowns on online opposition, portraying control over digital technology as a safeguard for Turkish values and moral rectitude. The strategic operationalization of religious values as a legitimizing force for digital authoritarianism is highly indicative of the AKP government’s efforts at consolidating power and suppressing opposition within the online sphere, profoundly shaping the contours of digital discourse and expression in Turkey.

Central to this strategy is the dissemination of Islamic values through state-managed religious institutions, traditional media, and social media platforms, all serving as conduits for aligning public sentiment with the government’s digital autocratic agenda. The propagation of Islamic tenets has been instrumental in molding public opinion to favor the government’s stringent and increasingly authoritarian approach to digital governance. In an effort to increase legitimacy and garner wider support, religious leaders and organizations have been strategically co-opted to support the government’s digital authoritarian agenda.

The cumulative effect of the integration of religion and digital governance has created a pervasive climate of censorship and self-censorship online. Individuals are discouraged from expressing dissenting views or disseminating information that could be perceived as contradictory to religious principles. This climate of caution and apprehension consequently serves to inhibit free expression and discourse within the digital realm, by not only fortifying the government’s authoritarian stance but also influencing the behavioral patterns of online users, curtailing the free flow of information and divergent opinions.

By adopting an interdisciplinary approach encompassing political science, religious studies, media analysis, and socio-political discourse, the paper aims to provide a comprehensive and empirically informed understanding of how religious justification has been systematically employed to legitimize methods of controlling voices of dissent online and foster a pro-AKP narrative in Turkey’s digital governance landscape.

This analysis will contribute to a deeper comprehension of the complex interplay between religion, politics, and digital authoritarianism in contemporary Turkey. This study will highlight how the ruling AKP fuse religion with the state’s digital agenda. It will also demonstrate their reliance on a network of religious platforms, figures, and media to reinforce the narrative of digital authoritarianism as a means of upholding Islamic values and protecting societal morality. The confluence of religious influence and governmental objectives, it will be argued, serves to shape public opinion and garner support for stringent control measures within the digital realm.

Religious Populism of Erdoganism and the AKP’s Authoritarianism

Since the country’s formation in 1923, Turkey has never been perceived as a highly democratic country from the perspective of Western libertarianism. Its initial phase featured a sort of national reconstruction from the worn-out centuries of the Ottoman Empire, which had faced a humiliating defeat at the hands of the Allied forces in World War One (WWI) towards the Republic. The Young Turks, who later became the Kemalists, set the country on a path of reformation with paradoxical ideas of modernization. While the country moved from a centuries-old monarchy to a parliamentary system, it remained far from democratic (Yilmaz’ 2021a). Between 1923 and 1946, Turkey was ruled by the Kemalist Republican People’s Party (CHP) alone. Even following the commencement of multi-party elections, the Turkish political and institutional landscape continued to be dominated by Kemalists until the AKP rose to power. The only exception was a brief period between 1996 and 1997 when Necmettin Erbakan and his right-wing Milli Gorus’s (National View) inspired Welfare Party (RP) held office (Yildiz, 2003).

The transition from Kemalism to Erdoganism, President Erdogan’s political ideology, was meticulously orchestrated, consolidating the state narrative and silencing opposing voices. The AKP initiated significant constitutional changes, starting with a referendum aimed at removing the Kemalist judiciary from power, and the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials which targeted key Kemalist military figures (Kuru, 2012: 51). Although these trials did not conclusively prove the accused’s ‘anti-state’ intentions, they significantly swayed public opinion against Kemalist control of the judiciary and military.

The 2010 Turkish Constitutional Referendum overwhelmingly favored the AKP, seeking increased control over the judiciary and military (Kalaycioglu, 2011). As a result, the outcome expanded parliamentary and presidential authority over appointments to the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK), enabling the AKP government to install its own appointees. This marked the end of Kemalist dominance in these institutions and paved the way for AKP influence – and an increasingly authoritarian agenda.

The AKP’s authoritarianism is distinguished from Kemalism by its adept blending of Islamist populism into its political discourse and agenda. While Kemalists championed secularism and Turkish nationalism, Erdoganists espouse an iron-fisted Islamist ideology rooted in the legacy of the Ottoman Empire. This has birthed a new form of autocracy known as “Erdoganism” (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018), characterized by four pivotal elements: electoral authoritarianism, neopatrimonialism, populism, and Islamism. (Yilmaz & Turner, 2019; Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018).

The socio-political landscape of Turkey has experienced a rapid decline, from an initially promising image of democratization to an authoritarian posture of governance with the ascent of AKP in 2002. The AKP’s transition from a seemingly pro-democracy to an authoritarian party has come to resemble the Kemalist tradition of violating democratic freedoms and rights (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018). Today, the public presence of the military, arbitrary crackdowns and arrests are now normalized activities of the Turkish state.

Erdogan’s dominant persona has resulted in the centralization of power around his leadership. This was particularly evident following the 2017 Constitutional Referendum, which transitioned the country into a Presidential system. Under this concentration of power, Erdoganism brought about an assimilation of the Turkish nation, state, and its economic, social, and political institutions (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018). By positioning himself as a referent object, Erdogan reinforces his grip on power while redefining the contours of Turkish identity, politics, and, as will be developed in this paper, the relationship between religion and the state (Yilmaz, 2000; Yilmaz, 2008, Yilmaz et al., 2021a; Yilmaz & Erturk 2022, 2021; Yilmaz et al., 2021b).

Co-opting of Religious Authorities and the Diyanet to Support AKP’s Authoritarian Agenda

President Erdogan has solidified the politicoreligious ideology of Erdoganism by fostering a close alliance with Turkey’s official religious authority, the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet). Initially established in 1924 by the Kemalist regime to centralize religious activities and advocate for a ‘secular’ form of Turkish Islam, Diyanet’s role has significantly expanded since the ascent of the AKP and has transformed to accommodate the party’s political Islamist identity.

This relationship is reflected in the increased budget allocation to the religious authority. The Turkish government’s 2023 budget proposal notably elevated Diyanet’s budget by 117 percent (Duvar, 2022). This influenced a substantial increase in funding grants, financial incentives and the heightened prestige of religious leaders and prominent imams. In return, Diyanet extends its loyalty and political support, including aligning with the AKP on digital policy and governance. President Erdogan strategically appoints pro-government religious figures such as Ali Erbas now President of Diyanet, to influential positions. Erbas, recognized for his religious conservatism, has cultivated a close relationship with President Erdogan and endorsed his call for a new Constitution (Martin, 2021).

Erbas’ conspicuous presence in public and political affairs underscores the intimate rapport between him and Erdogan. For instance, during the inauguration of the new Court of Cassation building, attended by President Erdogan, Erbas led a prayer praising its new location (Duvar, 2021). Additionally, Erbas represented President Erdogan at the funeral of Islamic cleric Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a supporter of Erdogan and the Muslim Brotherhood, in 2022 (Nordic Monitor, 2022). The building of ties between members of the government and the religious organization strengthens Diyanet’s role not just as a religious institution but also as a significant political force.

The Erdogan/AKP government has harnessed religious institutions, in particular mosques, to disseminate its positions and policies to the broader public through sermons, religious teachings, and various activities. A content analysis spanning from 2010 to 2021 reveals that Diyanet-run Friday sermons mirror the political stance of the AKP. These sermons were found to support Turkey’s involvement in the Syrian conflict, while vilifying ‘FETOists’—referring to the Gulen movement accused of terrorism. This analysis showcases how Diyanet employs affective religious rhetoric to endorse Erdogan’s decisions, discourage opposition, vilify perceived adversaries, propagate fear and conspiracies, and divert attention from the government’s shortcomings in areas spanning foreign policy, economics, and beyond (Yilmaz & Albayrak, 2022; Rogenhofer & Panievsky, 2020).

The Diyanet, has significantly expanded its media presence since 2010, operating television and radio channels, with an escalating expenditure on publicity. The organization and its leader Erbas also have an active presence and significant following on social media platforms such as YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook (Yilmaz & Albayrak, 2022). This heightened outreach has effectively filled the void created by the purge of groups like the Gulen movement and critical academic voices, both in the digital sphere and beyond (Yilmaz & Albayrak, 2022; Andi et al., 2020; Parkinson et al., 2014).

The close alliance between the Diyanet and the AKP has seen the past two heads of the organization employing faith-based justifications to support Erdogan’s moral campaign against perceived ‘internal’ and ‘external’ adversaries (Andi et al., 2020; Parkinson, et al., 2014). The increasingly stringent control over the digital sphere is justified by Diyanet with Islamic framing and justification. Thus, the emotionally charged narratives instrumentalized by the AKP (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018) have become directly intertwined with the religious directives and stances of the Diyanet (Yilmaz & Albayrak, 2022; Yilmaz et al., 2021a; Rogenhofer & Panievsky, 2020). Diyanet extends its influence not only within Turkish territories but also among the Turkish diaspora, functioning as an advisor for the AKP in diaspora communities. Consequently, through the transnational reach of the religious organization, the AKP’s authoritarian agenda has transcended national borders.

The Diyanet’s Moral Stance Against Social Media

Under the Presidential system, the President of Diyanet, appointed by Erdogan, wields significant influence as the centralized religious authority in Turkey and globally through its network of mosques (Danforth, 2020). Former President of Diyanet, Mehmet Gormez, openly criticized social media, attributing various societal harms to it. In 2016, Diyanet organized a forum titled “Social Media and the Family in the Context of Privacy,” aligning with the government’s calls for social media control. The forum aimed to emphasize traditional family values and discuss the perceived negative impact of social media on privacy and marriage. Gormez advocated for Diyanet to create a social media catechism, reinforcing the ideological harmony between Diyanet and Erdogan’s regime, consolidating authoritarianism both online and offline (Yilmaz & Albayrak, 2022; Yilmaz et al., 2021a; Danforth, 2020).

Diyanet has also actively engaged in efforts to exert stronger control over social media by publishing a booklet titled “Social Media Ethics,” using Islam as a guiding principle for this framework (Duvar, 2021). In the preface he personally authored, top imam Ali Erbas cautioned readers about the omnipotent governance of God extending to social media activities under Islamic law. Additionally, believers were alerted to the perils of “fake news” and urged to create a “world of truth” (Duvar, 2021; Turkish Minute, 2021).

Moreover, Diyanet’s Friday sermons have increasingly addressed themes related to social media, technology, and morality. On January 17, 2020, a sermon titled ‘Technology Addiction and Social Media Ethics’ was circulated by Diyanet, cautioning people about the dangers of the Internet violating the five fundamental values of Islam. It highlighted that the indiscriminate use of technology poses threats to human health, causes financial losses, erodes human dignity through unethical behaviors, undermines human faith with radical ideologies, and impairs cognitive abilities (Diyanet, 2020).

The Role of Islamic Scholars in Legitimizing the AKP Digital Authoritarian Agenda

Within academia, several pro-AKP Islamic scholars have aligned themselves with the government’s digital authoritarian agenda. Figures like Nihat Hatipoglu and Hayrettin Karaman (Kenes, 2018), associated with the AKP, believe that social media spreads misinformation targeting Turkish national interests and could mislead youth. Since 2016, Karaman, who has advised Erdogan on creating a more Islamist – and less tolerant – society has frequently accused social media of being used by “anti-Turkey” groups to spread lies (Yeni Safak, 2013). He highlights the dangers of false information being spread on these platforms, claiming that there’s no room for rebuttal (Yeni Safak, 2021). A poem written by Karaman supports AKP’s stance on social media, advocating for increased control to cultivate a “pious youth” and suppress critical remarks aimed at the AKP (Yeni Safak, 2020).

Nihat Hatipoglu, a prominent pro-AKP Turkish academic and theologian, has utilized his ATV show to issue fatwas, cautioning viewers about the potential sins associated with social media usage. For instance, he warns that engaging with “questionable” individuals on these platforms can lead to false rumors and sin, and accountability will come in the afterlife (Akyol, 2016). His messaging is potent in digital governance because it moves beyond conventional vices like alcohol or adultery and highlights the significance of sins associated with online behaviors and consumption, such as false testimonies and envy.

Furthermore, both Karaman and Hatipoglu are openly critical of “Western” media and social platforms, and advocate for Islamic content. Together, they represent a prevalent viewpoint supporting AKP discourse that emphasizes caution and adherence to Islamic principles while engaging with digital platforms.

Digital Authoritarian Measures Against the LQBTQ+ Community

The intersection of religion, politics, and social media in Turkey has also created a complex landscape where certain communities, particularly LGBTQ+ groups, have faced significant challenges. Religious leaders and government officials have used their platforms to vilify LGBTQ+ activists and communities, contributing to a hostile environment for these individuals (Greenhalgh, 2020).

This hostility has significantly deepened with anti-LQBTQ+ messaging from Turkish leadership. President Erdogan’s agenda has consistently focused on promoting a “pious youth” while openly expressing disapproval of atheists and LGBTQ+ identities as threats to societal and religious values (Gall, 2018). His party has employed rhetoric targeting Western values and certain youth groups, framing them as corruptive influences on Turkey’s future.

Although identifying as LGBTQ+ is not illegal in Turkey, the government has taken steps to restrict LGBTQ+ content and activism online (Woodward, 2019). This included censoring LGBTQ+ content on platforms like TikTok and imposing restrictions on advertising across social media channels to suppress opposition groups (Euronews, 2021).

Moreover, there have been instances of attempts to ban LGBTQ+ content, such as Netflix being prohibited from airing a movie with an LGBTQ+ storyline, and the mobilization of hashtags advocating for bans on LGBTQ+ content such as #LGBTfilmgunleriyasaklansin (#BanLGBTFilmDays); #İstiklalimizeKaraLeke (#StainOnOurIndependence) (Banka, 2020; Sari, 2018). These actions reflect the charged anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment prevalent in certain spheres of Turkish society and the state’s efforts to curtail LGBTQ+ visibility in the media and online discourse.

Government efforts at controlling and silencing LGBTQ+ members have clear repercussions in society. For example, influencing the demonization of LGBTQ+ youth during the Bogazici University protests in 2021 and subsequent limitations on LGBTQ+ content across various platforms (Kucukgocmen, 2021; Woodward, 2019; Euronews, 2021).

AKP’s Digital Network Control, Restrictions, and Bans

The Gezi Park protests in 2013 marked a turning point for the Turkish government’s efforts at controlling the digital landscape. During this period, civil society groups and activists turned to social media to coordinate the protests, prompting the government to denounce Twitter as a significant threat to society. Internet governance subsequently tightened, and internet blackouts were orchestrated by the newly established Telecommunication Technologies Authority (BTK) under government directives. While the government justified these internet restrictions as anti-terrorism measures, their political motives were evident.

The pinnacle of Turkish government internet shutdowns occurred between 2015 and 2017. This was facilitated by Internet Law No. 5651, introduced in 2007, permitting website blocking on multiple grounds, including for terrorism-related content. The broadened definition of “terrorism” that had been enacted by the Erdogan regime was manipulated to silence dissenting voices and serve the interests of the ruling power. Gradually, the scope of a “terrorist” in Turkey expanded to encompass peaceful protesters from events like the Gezi Park protests, anti-government activists labelled as “FETOists,” and students involved in activism during Istanbul’s Bogazici University events in 2021 (Wilks, 2021; Yesil et al., 2017).

Internet Law 5651 thus became a tool to marginalize digital spaces for non-AKP or critical groups, using the power of the TIB (Telecommunication and Information Technology Authority) and imposing additional responsibilities on hosting services and intermediaries. The 2014 amendment to the Law on State Intelligence Services granted the National Intelligence Service (MIT) authority to gather, record, and analyze public and private data, compelling intermediaries to comply with MIT’s requests under the threat of incarceration (Human Rights Watch, 2014).

The eastern regions of Turkey, particularly areas with strong Kurdish resistance, bore the brunt of internet and cellular shutdowns during critical events like the 2015 Suruc suicide bombing and the 2016 Ataturk Airport bombing. These shutdowns were often localized and imposed during high-risk security incidents. The government’s increasingly authoritarian approach leveraged digital anti-terrorism laws to target marginalized groups, particularly the Kurds. It is noteworthy that most shutdowns occurred in the southeast, where political activities are more prevalent. For instance, the 2016 closure of internet and landlines in 11 cities following the arrests of Diyarbakir’s mayor and co-mayor sparked protests and incurred significant economic costs for Turkey (Yackley, 2016).

Although internet shutdowns decreased from six in 2016 to one in 2020, the financial toll remains substantial, reaching $51 million in 2020 (Buchholz, 2021). While the precise role of religious justification and religious organizations in legitimizing comprehensive network governance remains unclear, their collaboration remains crucial to the government. It also plays a significant role in legitimizing various forms of digital governance and actions taken by the government – such as these internet shutdowns – that undermine democratic and digital freedom principles.

Digital Oppression Through the ‘Safe Use of the Internet’ Campaign

The 2011 “Safe Use of the Internet” campaign initiated by the Telecommunication Technologies Authority (BTK) promoted a Turkish-built filter called the ‘family filter.’ However, despite its name, the campaign primarily focused on regulating internet access in public spaces like cafes and libraries, rather than imposing ‘safe’ restrictions within domestic settings. The campaign purported to protect children from accessing non-age-appropriate content by blocking adult websites, both foreign and domestic. Interestingly, this campaign didn’t enforce mandatory installation of the ‘family filter’ at home, seemingly placing the responsibility on parents to supervise their children’s internet use. Discussions about children’s privacy were also notably absent from the campaign despite the stated objective (Hurriyet Daily News, 2014; Brunwasser, 2011).

Over time, concerns have emerged regarding the broader implications of the ‘family filter.’ Many speculate that this initiative, while supposedly aimed at blocking pornographic content, also serves as a tool for the state to censor critical voices within the digital space (Yesil et al., 2017). The criteria for blacklisting websites remain ambiguous, granting significant power to state authorities. By 2017, approximately 1.5 million websites had been blocked, particularly in public areas like cafes. The BTK has concerningly refrained from disclosing the list of websites it restricts (Yesil et al., 2017). The lack of transparency has contributed to concerns about digital oppression and censorship orchestrated by the AKP through the guise of protecting children and youth online.

AKP’s Digital Authoritarianism: Sub-Network, Website and Platform Level

The Internet Law (No. 5651) described above has facilitated the monitoring and blocking of webpages and websites in Turkey. Despite amendments, the law remains problematic due to its arbitrary and vague provisions. Internet governance institutions hold broad discretion in determining acceptable versus unacceptable content. According to Freedom House’s latest report, internet freedoms in Turkey have been increasingly restricted in recent years (Freedom House, 2021).

In 2006, prior to the introduction of the Internet Law, only four websites were blocked in Turkey. However, by 2008, this number had escalated to 1,014, reaching a staggering 27,812 in 2015. Government decisions using this law lack transparency and accountability, as blocking orders, often issued by the BTK, lack clear justifications, leaving website owners with limited recourse for appeal. Suspicion and precautionary measures are sometimes the sole reasons cited for blocking a website.

Following the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, websites related to the Gulen movement, Gezi Protests, corruption allegations, and terrorism charges were blocked or taken down (Ergun, 2018). Government actions also targeted websites advocating opposition, Kurdish rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and pornography. Several news outlets, including Zaman and Today’s Zaman, were shut down in 2016. Websites promoting atheism, such as the Atheism Association, were also blocked under Article 216 of the Turkish Penal Law, which prohibits actions inciting hatred or enmity among people (Hurriyet Daily News, 2015).

Digital Control at the Proxy or Corporation Level

The politicization and framing of the July 2016 events by Erdogan and the AKP as an assault on Turkish sovereignty triggered severe digital restrictions. The disbandment of the TIB over alleged pro-Gulenist ties led to the transfer of its powers to the Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK). Consequently, approximately 150 online and traditional media outlets were completely shut down, resulting in the loss of jobs for 2,700 Turkish journalists (Kocer & Bozdag, 2020). The legal framework governing digital spaces in Turkey has been wielded against opposition and civil society voices while favoring AKP and pro-AKP groups.

Social media intermediaries operating in Turkey have faced various restrictions. According to the Internet Law, they are required to comply with the Turkish government’s requests or face bans. During a period of heightened discontent against the AKP in 2014, the TIB pressured Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook to remove critical content damaging to the ruling party. While Facebook swiftly complied, Twitter and YouTube faced national blockades for several hours before eventually complying with the requests (Yesil et al., 2017). In 2016, Google also adhered to thousands of content removal requests from the Turkish state (Yesil et al., 2017).

The 2019 Transparency Reports from Twitter and Facebook shed light on Turkey’s extensive governmental demands for information and content removals. Twitter was issued with 350 information requests involving 596 accounts, and 6,073 removal requests affecting 8,993 accounts. The report indicated a compliance rate of 5 percent. Turkey was number one on the list for the highest number of legal demands for removals. Meanwhile, Facebook received 2,060 legal requests and 2,537 user information requests, complying with 73 percent of these requests (Freedom House, 2021).

Adding to this overall picture of digital surveillance and control, Turkey has imposed bans on approximately 450,000 domains, 140,000 URLs, and 42,000 tweets (Timuçin, 2021). IFOD announced on August 7, 2024, that by the end of the first quarter of that year, a total of 1,043,312 websites and domain names had been blocked in Turkey, based on 892,951 decisions from 833 different institutions and courts. The organization highlighted that this number could rise as more domain names are identified (IFOD, 2024). Furthermore, in 2017, Wikipedia was banned in Turkey following a ruling from Ankara’s first Criminal Court, linking certain articles to terror organizations. The court mandated edits to the articles before allowing the website to resume being accessible in the country in 2020 (Hurriyet Daily News, 2020; The Guardian, 2017).

The Turkish government’s manipulation of news and entertainment content distribution is a well-documented strategy, implemented through its control over media outlets both locally and internationally. Beyond influencing social media and restricting local websites, additional methods of control are exercised over television, streaming and various over-the-top media services (OTTs). In 2019, the government empowered the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTUK) to issue licenses and make them mandatory to access content streaming in Turkey (Pearce, 2019; Yerlikaya, 2019).

The Turkish government has also employed various financial penalties, including fines and heavy taxes, to curb critical voices and hinder their independent operations. These tactics have forced many critical media outlets out of business, enabling pro-government entities to acquire their assets. For instance, the pro-government Demiroren Group acquired the Dogan Media Group following high taxes imposed by the government. Anadolu Ajansi (AA), enjoying government support, has significantly increased its backing for the AKP government by 545 percent since 2002, with 91.1 percent of its Twitter coverage found to favor the government. The government’s informal means of bolstering pro-government content include shutting down anti-government entities and transferring or selling their outlets or platforms to pro-government supporters, establishing a clientelist relationship between the state and media (Yilmaz & Bashirov, 2018). For example, during the state of emergency in 2016, the Gulen-linked Samanyolu Group, Koza Ipek Group, and Feza Publications were seized and redistributed to President Erdogan’s loyalists (Timucin, 2021; BBC News, 2016; Yackley, 2016).

Digital Authoritarianism at the Network-Node or Individual Level

The Turkish government has intensified its crackdown on individual social media and online activities, particularly following the 2016 coup attempt. The Ministry of Interior, for example, reported investigations on over ten thousand individuals for their online engagements, resulting in legal action against over 3,700 and the arrest of more than 1,600 people. Within a two-month span between January and March 2018, over 6,000 social media accounts were probed, leading to legal consequences for over 2,000 individuals. Freedom House’s 2021 assessment further revealed that between 2013 and 2018, the government initiated over 20,000 legal cases against citizens due to their social media activities (Ergun, 2018).

A climate of self-censorship among Turkish internet users has become entrenched. This is owing to multiple actions and crackdowns taken by the government in recent years. Following the coup attempt, for example, academics and civil society voices were targeted by pro-AKP media outlets that alleged their involvement in “terrorism” (GIT North America, 2016). Journalists have faced a diminished space to express dissenting opinions and face being accused of or charged with terrorism under various legal articles, including Article 314/2, related to association with armed organizations, and Article 147 and Article 5, concerning crimes associated with terrorist intent and groups (Sahinkaya, 2021). The restriction of anti-AKP voices has heavily tilted mainstream conversation in favor of pro-AKP narratives, dominating both online and offline domains.

The Turkish government actively suppresses dissent on social media, resorting to threats and arrests against individuals. In a 2014 incident, a Turkish court ordered Facebook to block pages and individuals engaging with content from Charlie Hebdo, a French magazine that published a cartoon insulting Prophet Muhammad (Johnston, 2015). The Director of Communications of the Presidency warned citizens in May 2020 that even liking or sharing a post deemed unacceptable by the government could lead to trouble. Journalists, scholars, opposition figures, and civil society leaders critical of the government are increasingly vulnerable to prosecution.

The AKP’s influence in the digital public sphere is also notable in its internet trolling and online harassment campaigns, which are aimed at shaping narratives in favor of the party and against the opposition. Critics of the AKP, including journalists, academics, and artists, face a culture of “digital lynching and censorship” perpetrated by an army of party-affiliated trolls (Bulut & Yoruk, 2017). Post-2016, this situation has worsened, subjecting critical voices to intensified cyberbullying and making their persecution more challenging (Shearlaw, 2016). Many of these trolls are graduates of pro-AKP Imam Hatip schools and reportedly receive a payment. Successful trolls likely receive additional benefits from pro-AKP networks, including the TRT and Turkcell (Bulut & Yoruk, 2017). In addition to employing trolls, the AKP also uses automated bots to amplify its presence in the digital space, disproportionately projecting their narrative across platforms (Irak & Ozturk, 2018).

The manipulation of social media platforms across the globe has become a significant concern, and this is particularly the case in Turkey. In 2020, Twitter’s deletion of a substantial number of accounts from China, Russia, and Turkey revealed the extent of propaganda spread by these accounts. Many were focused on supporting President Erdogan, attacking opposition parties, and advocating for undemocratic reforms (Twitter Safety, 2020). The proliferation of fake accounts and bots, and the significant portion of posts originating from these accounts, has skewed the representation of daily Twitter (renamed as X) trends, and consequently affected political discourse.

Disturbingly, instances of online harassment and hate speech targeting individuals based on their political stance or ethnic background have been observed without effective intervention. For instance, Garo Paylan, an HDP deputy with Turkish-Armenian heritage, faced online harassment for his political stance during the Azerbaijan-Armenian skirmish in 2020 (Briar, 2020). Meanwhile, controversial statements, such as Ibrahim Karagul’s suggestion of ‘accidentally’ bombing Armenians, didn’t receive the same scrutiny for hate speech (Barsoumian, 2020).

Conclusion

The merging of religion and the state’s digital authoritarian agenda serves as a potent tool for steering public opinion, validating control mechanisms, and fortifying the government’s authority. It exemplifies how the discourse of upholding Islamic values and societal morality can be strategically harnessed to garner support for stringent digital control measures, influencing public perception and behavior within the digital landscape.

This article identifies numerous ways the AKP and its leader, administer their authority over the digital realm in Turkey. Voices of dissent and opposition are silenced through the enactment of a range of legislative and strategic measures, such as Internet Law No.5651, the “Safe Use of the Internet” campaign, and online trolling and harassment practices that directly target critics of the government. Additionally, the AKP make considerable attempts at controlling the online content its citizenry can or want to access; the discussion highlights the internet lockdowns, blacklisting of websites, and issuing warnings to Turkish citizens of the consequences of engaging with certain (oppositional) content.

The above measures are supported and legitimized by the AKP and Erdogan’s religious discourse, and through its network of pro-AKP religious authorities including the Diyanet, Islamic scholars and preachers. By aligning digital control measures with Islamic values and societal morality, the government can justify its actions as essential for preserving the ethical fabric of society. This moral grounding lends an air of legitimacy and righteousness to measures that might otherwise be viewed as intrusive or oppressive.

The fusion of religious rhetoric with digital governance acts as a deterrent to dissent. The government discourages dissenting voices by associating opposition to these measures with a departure from religious principles, fostering a climate of self-censorship and compliance within the digital sphere.

Religious institutions, particularly Diyanet, are heavily influential in conversations about social media ethics and endorsing greater control over digital spaces, leading to an Islamization of digital spaces. Strict limitations on blasphemy and criticism of Islamic beliefs curtail freedom of expression online.

Ultimately, the combination of information and content control, legal measures, religious influence, and online manipulation creates a challenging scenario for digital governance in Turkey. These various elements work together to shape narratives, control dissent, create a pervasive environment of censorship and self-censorship, and restrict freedoms in the digital realm, impacting the country’s broader socio-political landscape.

References

— (2014). “Turkey: Spy Agency Law Opens Door to Abuse.” Human Rights Watch (HRW). April 29, 2014. https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/04/29/turkey-spy-agency-law-opens-door-abuse (accessed on August 17, 2024).

— (2014). “’Turkey’s new Internet law is the first step toward surveillance society,’ says cyberlaw expert.” Hurriyet Daily News. February. 24, 2014 https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkeys-new-internet-law-is-the-first-step-toward-surveillance-society-says-cyberlaw-expert-62815 (accessed on August 27, 2024).

— (2015). “Turkey Blocks Website of Its First Atheist Association.” Hurriyet Daily News. March 4, 2015. https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-blocks-website-of-its-first-atheist-association-79163 (accessed on August 22, 2024).

— (2016). “Zaman newspaper: Seized Turkish daily ‘now pro-government’.” BBC News. March 6, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35739547 (accessed on August 18, 2024).

— (2017). “Turkey blocks Wikipedia under law designed to protect national security.” The Guardian. April 30, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/29/turkey-blocks-wikipedia-under-law-designed-to-protect-national-security (accessed on August 21, 2024).

— (2017). “Turkey reverses female army officers’ headscarf ban.” BBC News. February 22, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39053064 (accessed on August 18, 2024).

— (2017a). “Turkey arrests 1,000 in raids targeting Gulen suspects.” BBC News. April 26, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39716631 (accessed on August 18, 2024).

— (2019). “Turkey’s post-coup crackdown.” Turkey Purge. https://turkeypurge.com/

— (2020). “Disclosing networks of state-linked information operations we’ve removed.” Twitter Safety. June 12, 2020. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2020/information-operations-june-2020 (accessed on October 21, 2023).

— (2020). “Turkey court jails hundreds for life for 2016 coup plot against Erdogan.” BBC News. November 26, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-55083955 (accessed on August 18, 2024).

— (2020). “Wikipedia ban lifted after top court ruling issued.” Hurriyet Daily News. January 15, 2020.https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/wikipedia-ban-lifted-after-top-court-ruling-issued-150993 (accessed on August 12, 2024).

— (2020). “There are 54 million social media users in Turkey.” Bianet. July 2, 2020. https://m.bianet.org/english/society/226764-there-are-54-million-social-media-users-in-turkey (accessed on August 17, 2024).

— (2020). “Technology Addiction and Social Media Ethics.” Diyanet. January 17, 2020. https://dinhizmetleri.diyanet.gov.tr/Documents/Technology%20Addiction%20and%20Social%20Media%20Ethics.doc

— (2020). “Turkey.” Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkey/freedom-net/2020 (accessed on August 14, 2024).

— (2021). “Individuals using the Internet (% of population).” World Bank Data Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=TR (accessed on August 15, 2024).

— (2021). “Turkey’s top imam calls for social media regulation amid discussions on new gov’t body.” Turkish Minute.September 7, 2021. https://www.turkishminute.com/2021/09/07/rkeys-top-imam-calls-for-social-media-regulation-amid-discussions-on-new-government-body/ (accessed on October 21, 2023).

— (2021). “Turkey: Events of 2020.” Human Rights Watch (HRW). https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/turkey#8e519f (accessed on August 17, 2024).

— (2021). “Turkey bans advertising on Twitter and Pinterest under social media law.” Euronews. January 19, 2021. https://www.euronews.com/2021/01/19/turkey-bans-advertising-on-twitter-and-pinterest-under-social-media-law (accessed on August 14, 2024).

— (2021). “Turkish religious authority recommends Islamic jurisprudence to curb social media in new book.” Duvar.September 7, 2021. https://www.duvarenglish.com/turkish-religious-authority-recommends-islamic-jurisprudence-to-curb-social-media-in-new-book-news-58737 (accessed on August 12, 2024).

— (2021). “Turkish Parliament to create ‘digital map’ of country.” Daily Sabah. May 24, 2021. https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/legislation/turkish-parliament-to-create-digital-map-of-country (accessed on August 23, 2024).

— (2021a). “Turkey to open social media directorate.” Daily Sabah. August 23, 2021. https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/legislation/turkey-to-open-social-media-directorate (accessed on August 23, 2024).

— (2021b). “Rate of internet users in Turkey rises to 82.6%.” Daily Sabah. August 26, 2021. https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/rate-of-internet-users-in-turkey-rises-to-826/news (accessed on August 23, 2024).

— (2022). “More than 2 million terrorism investigations launched in Turkey following failed coup: official data.” Turkish Minute. December 13, 2022. https://www.turkishminute.com/2022/12/13/e-than-2-million-terrorism-investigations-launched-in-turkey-following-failed-coup-official-data/ (accessed on August 29, 2024).

— (2022). “Erdoğan sent his chief imam to the funeral of cleric who endorsed suicide bombings.” Nordic Monitor.October 3, 2022. https://nordicmonitor.com/2022/09/erdogan-sent-his-chief-imam-to-the-funeral-of-cleric-who-endorsed-suicide-bombings/ (accessed on August 7, 2024).

— (2024). “1 Milyondan Fazla Alan Adı Erişime Engelli.” IFOD. August 7, 2024. https://ifade.org.tr/engelliweb/1-milyondan-fazla-alan-adi-erisime-engelli/ (accessed on August 9, 2024).

Akyol, A.R. (2016). “Iranian film about Prophet Muhammad causes stir in Turkey”. Al Monitor. November 15, 2016. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2016/11/turkey-iranian-movie-about-prophet-causes-stir.html#ixzz7BczW8uvz (accessed on August 19, 2024).

Andi, S.S.; Erdem A. & Carkoglu, A. (2020). “Internet and social media use and political knowledge: Evidence from Turkey.” Mediterranean Politics (Frank Cass & Co.). 25(5), 579–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2019.1635816

Banka, N. (2019). “Why Netflix cancelled a Turkish drama after row over an LGBTQ character.” Indian Express. July 22, 2019. https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-why-netflix-cancelled-a-turkish-drama-after-row-over-an-lgbtq-character-6518401/# (accessed on August 11, 2024).

Barsoumian, Nanore. (2020). “Sharp Rise in Hate Speech Threatens Turkey’s Armenians.” Armenian Weekly. October 8, 2020. https://armenianweekly.com/2020/10/08/sharp-rise-in-hate-speech-threatens-turkeys-armenians/ (accessed on August 18, 2024).

Bellut, D. (2021). “Turkish government increases pressure on social media.” DW. September 9, 2021. https://www.dw.com/en/turkish-government-increases-pressure-on-social-media/a-59134848 (accessed on August 13, 2024).

Briar, N. (2020). “Negligent Social Media Platforms Breeding Grounds for Turkish Nationalism, Hate Speech.” The Armenian Weekly. October 29, 2020. 2020https://armenianweekly.com/2020/10/29/negligent-social-media-platforms-breeding-grounds-for-turkish-nationalism-hate-speech/ (accessed on August 23, 2024).

Brunwasser, M. (2011). “Turkish Internet filter to block free access to information.” DW. January 6, 2011. https://www.dw.com/en/turkish-internet-filter-to-block-free-access-to-information/a-15123910 (accessed on August 30, 2024).

Buchholz, K. (2021). “The Cost of Internet Shutdowns.” Statista. January 6, 2021. https://www.statista.com/chart/23864/estimated-cost-of-internet-shutdowns-by-country/ (accessed on August 28, 2024).

Bulut, E. & Yoruk, E. 2017. “Digital Populism: Trolls and Political Polarization of Twitter in Turkey.” International Journal of Communication. 11, 4093–4117.

Conditt, Jessica. (2016). “Turkey shuts off internet service in 11 Kurdish cities.” Engadget. October 27, 2016. https://www.engadget.com/2016-10-27-turkey-internet-shutdown-kurdish-cities.html (accessed on August 22, 2024).

Danforth, N. (2020). “The Outlook for Turkish Democracy: 2023 and Beyond.” Washington Institute for Near East Policy. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/media/632 (accessed on August 12, 2024).

Colborne, Michael & Edwards, Maxim. (2018). “Erdogan’s Long Arm: The Turkish Dissidents Kidnapped from Europe.” Haaretz. August 30, 2018. https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/turkey/.premium-erdogan-s-long-arm-the-turkish-nationals-kidnapped-from-europe-1.6428298 (accessed on August 13, 2024).

Elmas, Tugrulcan. (2023). “Analyzing Activity and Suspension Patterns of Twitter Bots Attacking Turkish Twitter Trends by a Longitudinal Dataset.” ArXiv. April 16, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.07907 (accessed on August 23, 2024).

Ergun, D. (2018). “National Security vs. Online Rights and Freedoms in Turkey: Moving Beyond the Dichotomy.” Centre for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies (EDAM). https://edam.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/TurkeyNational-Security-vs-Online-Rights.pdf

Gall, C. (2018). “Erdogan’s Plan to Raise a ‘Pious Generation’ Divides Parents in Turkey.” The New York Times. June 18, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/18/world/europe/erdogan-turkey-election-religious-schools.html (accessed on August 3, 2024).

GIT North America. (2016). “Pro-AKP Media Figures Continue to Target Academics for Peace.” Jadaliyya. April 27, 2016. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/33208 (accessed on August 23, 2024).

Greenhalgh, Hugo. (2020). “Hundreds of global faith leaders call for ban on LGBT+ conversion therapy.” Reuters.December 16, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/hundreds-of-global-faith-leaders-call-for-ban-on-lgbt-conversion-therapy-idUSKBN28Q00T/ (accessed on August 22, 2024).

Homberg, J.; Said-Moorhouse, L. & Fox, K. (2017). “47,155 arrests: Turkey’s post-coup crackdown by the numbers.” CNN. April 15, 2017. https://edition.cnn.com/2017/04/14/europe/turkey-failed-coup-arrests-detained/index.html (accessed on August 27, 2024).

Irak, D. & Ozturk, A. E. (2018). “Redefinition of State Apparatuses: AKP’s Formal-Informal Networks in the Online Realm.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies. 20(5), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2018.1385935

Johnston, C. (2015). “Facebook Blocks Turkish Page That ‘Insults Prophet Muhammad’.” The Guardian. January 27, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jan/27/facebook-blocks-turkish-page-insults-prophet-muhammad (accessed on August 27, 2024).

Kalaycioglu, E. (2012). “Kulturkampf in Turkey: The Constitutional Referendum of 12 September 2010.” South European Society & Politics. 17(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2011.600555

Karaman, Hayreddin. (2013). “Çoğunluğu kale almamak.” Yeni Safak. November 7, 2013. https://www.yenisafak.com/yazarlar/hayrettin-karaman/cogunlugu-kale-almamak-40566 (accessed on September 1, 2024).

Karaman, Hayreddin. (2020). “İnternet deryası ve pazarı.” Yeni Safak. October 25, 2020. https://www.yenisafak.com/yazarlar/hayrettin-karaman/internet-deryasi-ve-pazari-2056600 (accessed on September 1, 2024).

Karaman, Hayreddin. (2021). “Sosyal medya yalanları.” Yeni Safak. October 10, 2021. https://www.yenisafak.com/yazarlar/hayrettin-karaman/sosyal-medya-yalanlari-2059831 (accessed on September 1, 2024).

Kemp, S. (2024). “Digital 2024: Turkey.” Datareportal. February 23, 2024. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-turkey (accessed on August 18, 2024).

Kenes, Bulent. (2018). “Instrumentalization of Islam: Hayrettin Karaman’s Role in Erdogan’s Despotism.” Politurco.May 30, 2018. https://politurco.com/instrumentalization-of-islam-hayrettin-karamans-role-in-erdogans-despotism.html (accessed on September 1, 2024).

Kocer, S. & Bozdag, C. (2020). “News-Sharing Repertoires on Social Media in the Context of Networked Authoritarianism: The Case of Turkey.” International Journal of Communication. 14: 5292-5310. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/13134

Kuru, A.T. (2012). “The Rise and Fall of Military Tutelage in Turkey: Fears of Islamism, Kurdism, and Communism.” Insight Turkey. 14(2): 37–57.

Kucukgocmen, A. (2021). “Twitter labels Turkish minister’s LGBT post hateful as students protest.” Reuters. February 2, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/turkey-security-bogazici-int-idUSKBN2A21C1 (accessed on August 21, 2024).

Martin, Jose Maria. (2021). “Turkey’s judiciary calls on Ali Erbas to tone it down.” Atalayar. September 10, 2021. https://www.atalayar.com/en/articulo/politics/turkeys-judiciary-calls-ali-erbas-tone-it-down/20210909133027152860.html (accessed on August 19, 2024).

Parkinson, J.; Schechner, S. & Peker, E. (2014). “Turkey’s Erdogan: One of the World’s Most Determined Internet Censors.” The Wall Street Journal. May 2, 2014. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304626304579505912518706936 (accessed on August 12, 2024).

Pearce, J. (2019). “Turkey to introduce new regulations for OTT services.” IBC. August 6, 2019. https://www.ibc.org/trends/turkey-to-introduce-new-regulations-for-ott-services/4239.article (accessed on August 16, 2024).

Rogenhofer, J. M. & Panievsky, A. (2020). “Antidemocratic populism in power: comparing Erdoğan’s Turkey with Modi’s India and Netanyahu’s Israel.” Democratization. 27(8), 1394–1412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1795135

Sahinkaya, E. (2021). “Erdogan Says Media Are ‘Incomparably Free,’ But Turkish Journalists Disagree.” VoA. October 13, 2021. https://www.voanews.com/a/turkey-erdogan-press-freedom/6269435.html (accessed on August 11, 2024).

Shearlaw, M. (2016). “Turkish journalists face abuse and threats online as trolls step up attacks.” The Guardian. November 1, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/01/turkish-journalists-face-abuse-threats-online-trolls-attacks (accessed on August 1, 2024).

Timucin, Fatma. (2021). 8-Bit Iron Fist: Digital Authoritarianism in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes: The Cases of Turkey and Hungary. (Master’s thesis, Sabanci University, Istanbul, Turkey). https://research.sabanciuniv.edu/42417/(accessed on August 21, 2024).

Westendarp, L. (2021). “Turkey orders arrests in latest crackdown on Gülen network.” Politico. October 19, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/turkey-arrest-crackdown-fethullah-gulen-network/ (accessed on August 11, 2024).

Wilks, A. (2021). “Turkey’s student protests: New challenge for Erdogan.” Al Jazeera. February 6, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/2/6/turkeys-student-protests-new-challenge-for-erdogan (accessed on August 15, 2024).

Woodward, A. (2019). “Documents Reveal That TikTok Once Banned LGBTQ, Anti-Government Content in Turkey.” Forbes. October 2, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/annabellewoodward1/2019/10/02/documents-reveal-that-tiktok-once-banned-lgbtq-anti-government-content-in-turkey/?sh=5145d5c81d7e (accessed on August 15, 2024).

Yabanci, B. (2019). Work for the Nation, Obey the State, Praise the Ummah: Turkey’s Government-oriented Youth Organizations in Cultivating a New Nation. Ethnopolitics, 20(4), 467–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2019.1676536

Yackley, J.A. (2016). “Turkey closes media outlets seized from Gulen-linked owner.” Reuters. March 1, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-media-gulen-idUSKCN0W34MLa (accessed on August 15, 2024).

Yerlikaya, T. (2019). “Supervision or Censorship? Turkey’s Regulation on Netflix and Web-Based Broadcasting.” Politics Today. August 29, 2019. https://politicstoday.org/supervision-or-censorship-turkeys-regulation-on-netflix-and-web-based-broadcasting/ (accessed on August 15, 2024).

Yesil, B.; Efe, K.Z. & Khazraee, E. (2017). “Turkey’s Internet Policy After the Coup Attempt: The Emergence of a Distributed Network of Online Suppression and Surveillance.” Internet Policy Observatory. https://repository.upenn.edu/internetpolicyobservatory/22 (accessed on August 25, 2024).

Yildiz, A. (2003). “Politico-Religious Discourse of Political Islam in Turkey: The Parties of National Outlook.” The Muslim World (Hartford). 93(2), 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/1478-1913.00020

Yilmaz, I. (2000). “Changing institutional Turkish-Muslim discourses on modernity, West and dialogue.” Congress of The International Association of Middle East Studies (IAMES). Freie Universitat Berlin, Germany, October 2000.

Yilmaz, I. (2008). “Influence of Pluralism and Electoral Participation on the Transformation of Turkish Islamism,” Journal of Economic and Social Research. 10(2): 43-65.

Yilmaz, I. (2009a). “Predicaments and Prospects in Uzbek Islamism: A Critical Comparison with the Turkish Case.” USAK Yearbook of International Politics and Law, 2: 321-347.

Yilmaz, I. (2009b). “An Islamist Party, Constraints, Opportunities and Transformation to Post-Islamism: The Tajik Case.” Uluslararası Hukuk ve Politika. 5(18), 133–147.

Yilmaz, I. (2009c). “Socio-Economic, Political and Theological Deprivations’ Role in the Radicalization of the British Muslim Youth: The Case of Hizb ut-Tahrir.” European Journal of Economic and Political Sciences 2(1): 89-101.

Yilmaz, I. (2009d). “Was Rumi the Chief Architect of Islamism? A Deconstruction Attempt of the Current (Mis)Use of the Term ‘Islamism’.” European Journal of Economic and Political Studies. 2(2): 71-84.

Yilmaz, I. (2010a). “A Comparative Analysis of Anti-Systemic Political Islam: Hizb ut-Tahrir’s Influence in Different Political Settings (Britain, Turkey, Egypt and Uzbekistan).” In: Michelangelo Guida and Martin Klus (eds) Turkey and The European Union: Challenges and Accession Perspectives. Bruylant, 253-268.

Yilmaz, I. (2016b). “The Experience of the AKP: From the Origins to Present Times.” In: Alessandro Ferrari and James Toronto (eds) Religions and Constitutional Transitions in the Muslim Mediterranean: The Pluralistic Moment. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2016, 162-175.

Yilmaz, I. (2018a). “Islamic Populism and Creating Desirable Citizens in Erdogan’s New Turkey.” Mediterranean Quarterly. 29(4): 52-76. https://doi.org/10.1215/10474552-7345451

Yilmaz, I. & Bashirov, G. (2018). The AKP after 15 years: emergence of Erdoğanism in Turkey. Third World Quarterly. 39(9): 1812–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1447371

Yilmaz, I. (2019c). “Potential Impact of the AKP’s Unofficial Political Islamic Law on the Radicalisation of the Turkish Muslim Youth in the West.” In: Mansouri F., Keskin Z. (eds) Contesting the Theological Foundations of Islamism and Violent Extremism. Middle East Today. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2019, 163-184. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02719-3_9

Yilmaz, I. (2020a). “Islamist Populism in Turkey, Islamist Fatwas and State Transnationalism.” In: Shahram Akbarzadeh (ed) The Routledge Handbook of Political Islam, 2nd Edition. London and New York: Routledge.

Yilmaz, I. (2021a). Creating the Desired Citizens: State, Islam and Ideology in Turkey. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Yilmaz, I. (2021b). “Islamist Populism in Turkey, Islamist Fatwas and State Transnationalism.” In: Shahram Akbarzadeh (ed) The Routledge Handbook of Political Islam, 2nd Edition, 170-187. London and New York: Routledge.

Yilmaz, I. & Albayrak, I. (2022). Populist and Pro-Violence State Religion: The Diyanet’s Construction of Erdoğanist Islam in Turkey. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Yilmaz, I.; Demir, M. & Morieson, N. (2021a). “Religion in Creating Populist Appeal: Islamist Populism and Civilizationism in the Friday Sermons of Turkey’s Diyanet.” Religions. 12: 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050359/

Yilmaz, I.; Shipoli, E. & Demir, M. (2021b). “Authoritarian resilience through securitization: an Islamist populist party’s co-optation of a secularist far-right party.” Democratization. 28(6), 1115–1132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1891412

Yilmaz, I. & Erturk, O. (2022). “Authoritarianism and necropolitical creation of martyr icons by Kemalists and Erdoganists in Turkey.” Turkish Studies. 23(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2021.1943662

Yilmaz, I. & Erturk, O. F. (2021). “Populism, violence and authoritarian stability: necropolitics in Turkey.” Third World Quarterly. 42(7), 1524–1543. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1896965

Yılmaz, Z. & Turner, B. S. (2019). “Turkey’s deepening authoritarianism and the fall of electoral democracy.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 46(5), 691–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2019.1642662

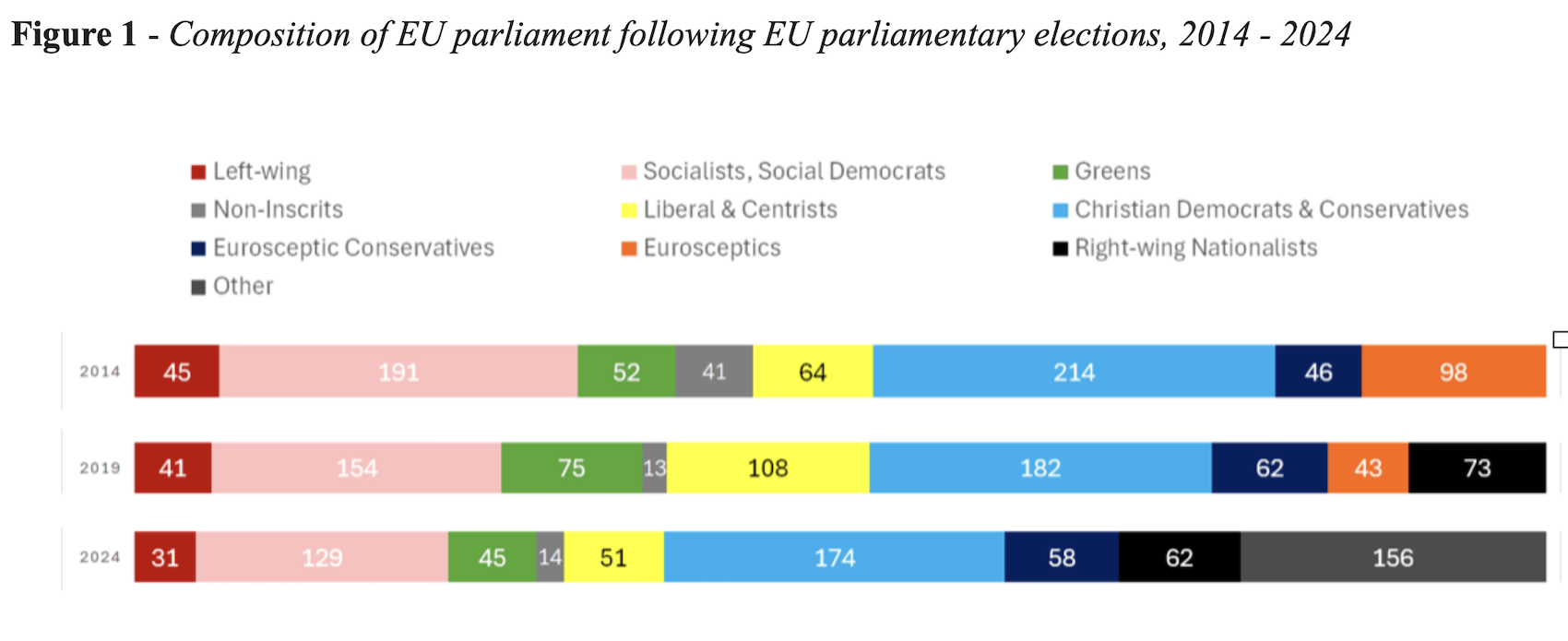

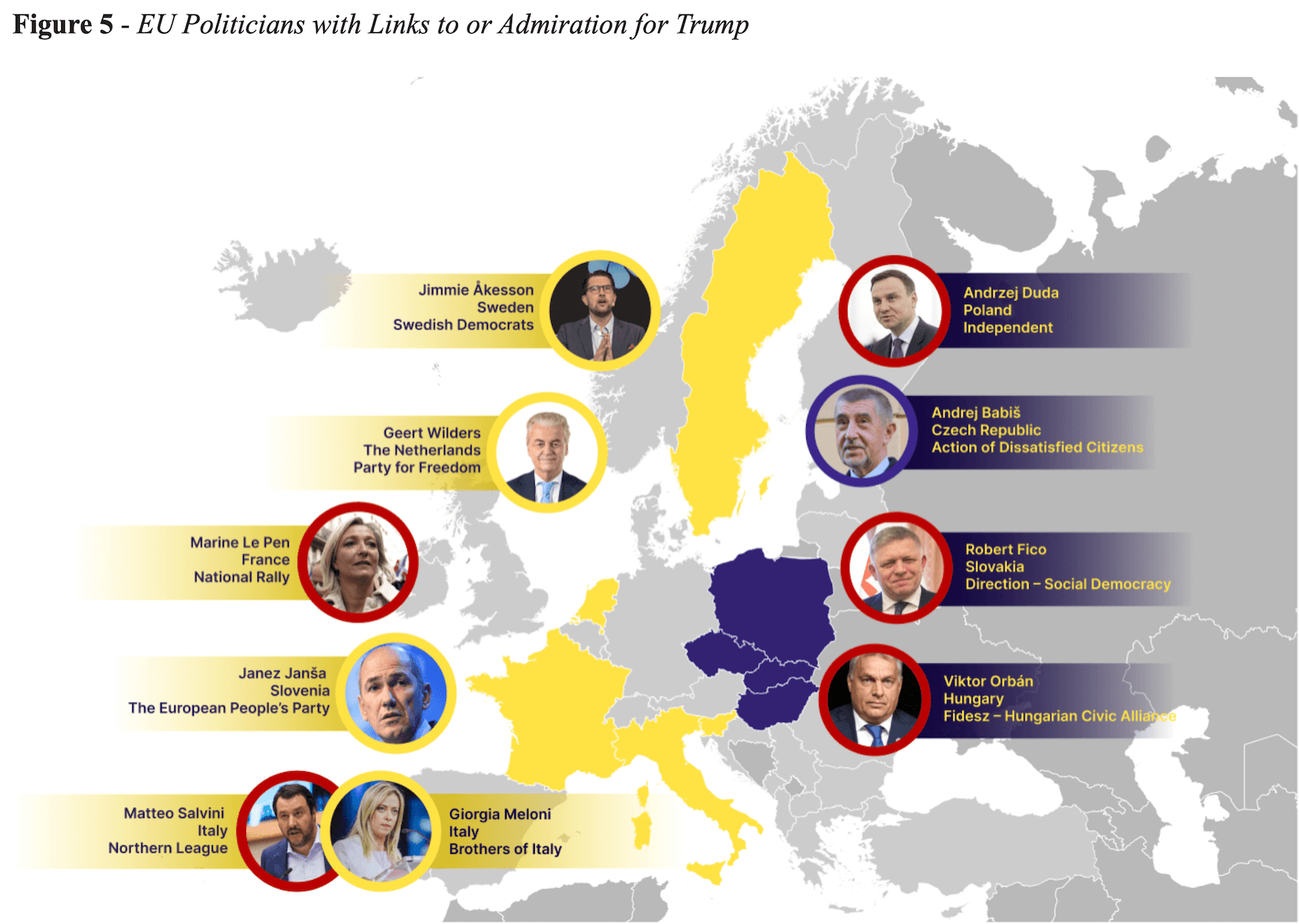

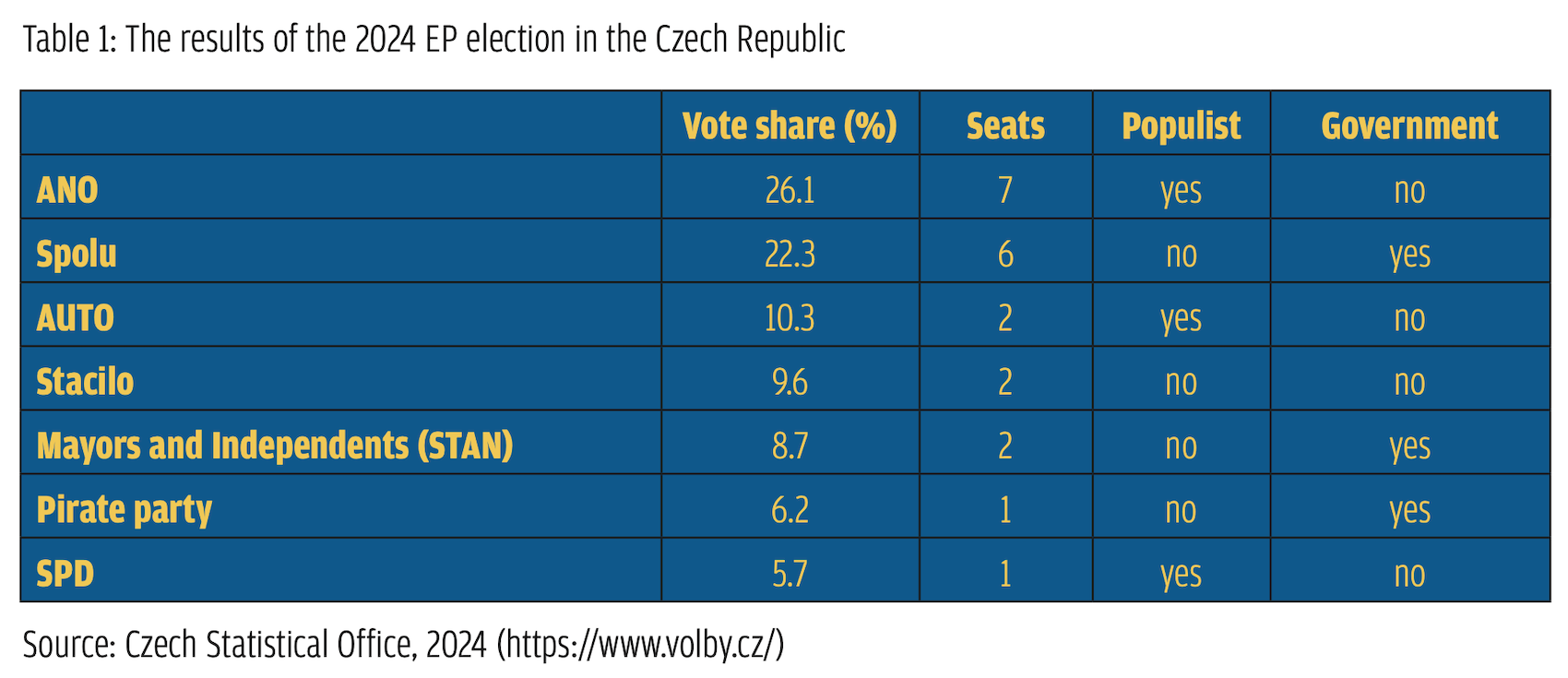

Europe has also faced difficulties controlling the increasing numbers of its migrant population. According to the International Organization for Migration (McAuliffe & Oucho, 2024), there are approximately 87 million migrants living in Europe. In the context of migration crises, which often disproportionately impact EU member states, balancing European cohesion has fragmented the Union. Additionally, in recent years, Western politics has witnessed a trend of a right-wing shift (see Figure 1) and increased support for populist leaders, which exacerbates this fragmentation (Europe Elects, 2024; Europe Politique, 2024).

Europe has also faced difficulties controlling the increasing numbers of its migrant population. According to the International Organization for Migration (McAuliffe & Oucho, 2024), there are approximately 87 million migrants living in Europe. In the context of migration crises, which often disproportionately impact EU member states, balancing European cohesion has fragmented the Union. Additionally, in recent years, Western politics has witnessed a trend of a right-wing shift (see Figure 1) and increased support for populist leaders, which exacerbates this fragmentation (Europe Elects, 2024; Europe Politique, 2024).