Please cite as:

ECPS Staff. (2025). “ECPS Conference 2025 / Panel 8 — ‘The People’ vs ‘The Elite’: A New Global Order?” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). July 9, 2025. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00108

At the 2025 ECPS Conference in Oxford, Panel 8 offered a rich exploration of populism, elite transformation, and democratic erosion. Co-chaired by Ashley Wright (Oxford) and Azize Sargın (ECPS), the session featured cutting-edge scholarship from Aviezer Tucker, Pınar Dokumacı, Attila Antal, and Murat Aktaş. Presentations spanned elite populism, feminist spatial resistance, transatlantic authoritarianism, and the metapolitics of the French New Right. Discussant Karen Horn (University of Erfurt) offered incisive critiques on intellectual transmission, rationalism, and democratic thresholds. Together, the panel underscored populism’s global diffusion and its capacity to reshape both elites and “the people,” demanding renewed theoretical and civic engagement. Democracy, the panel emphasized, remains a contested space—never static, always in motion.

Reported by ECPS Staff

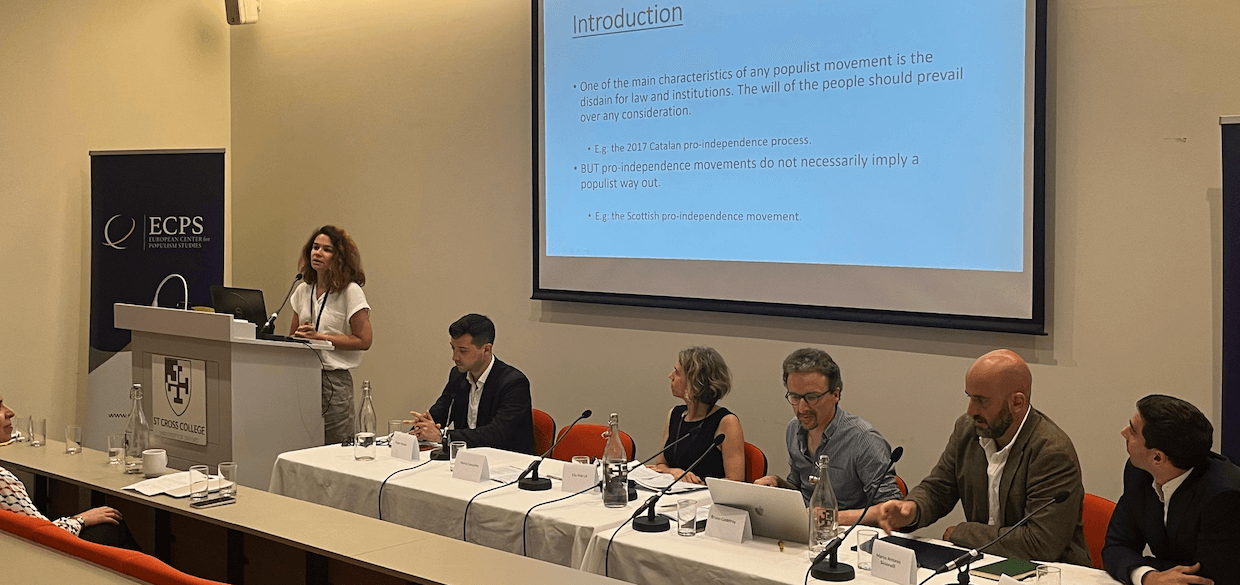

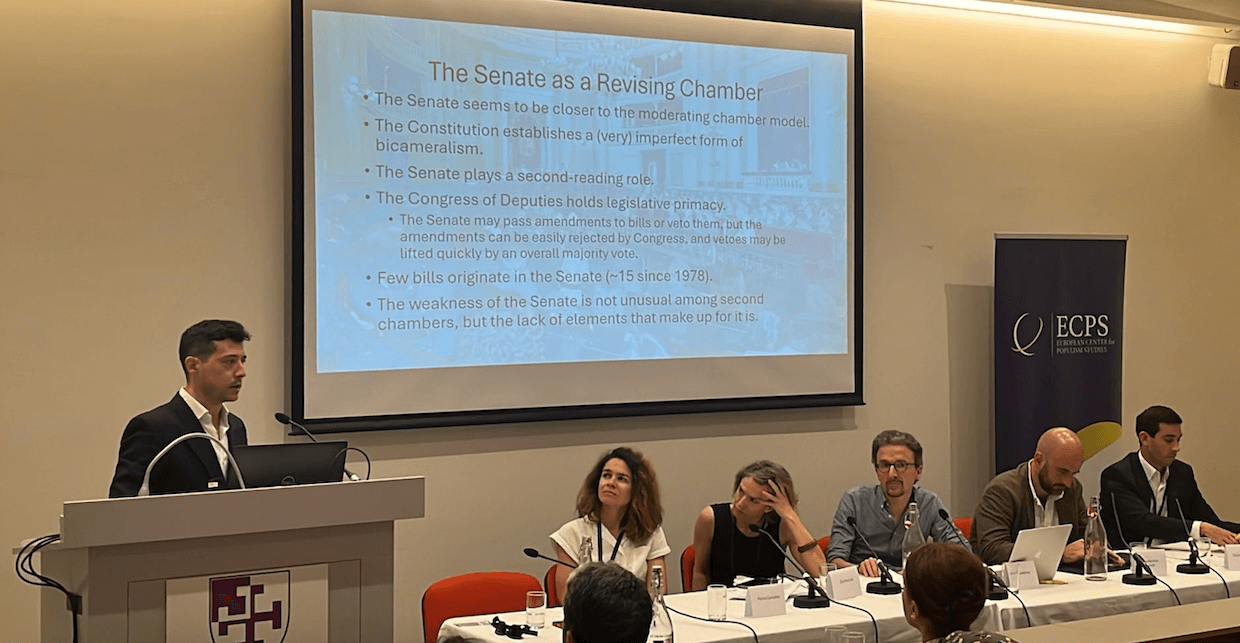

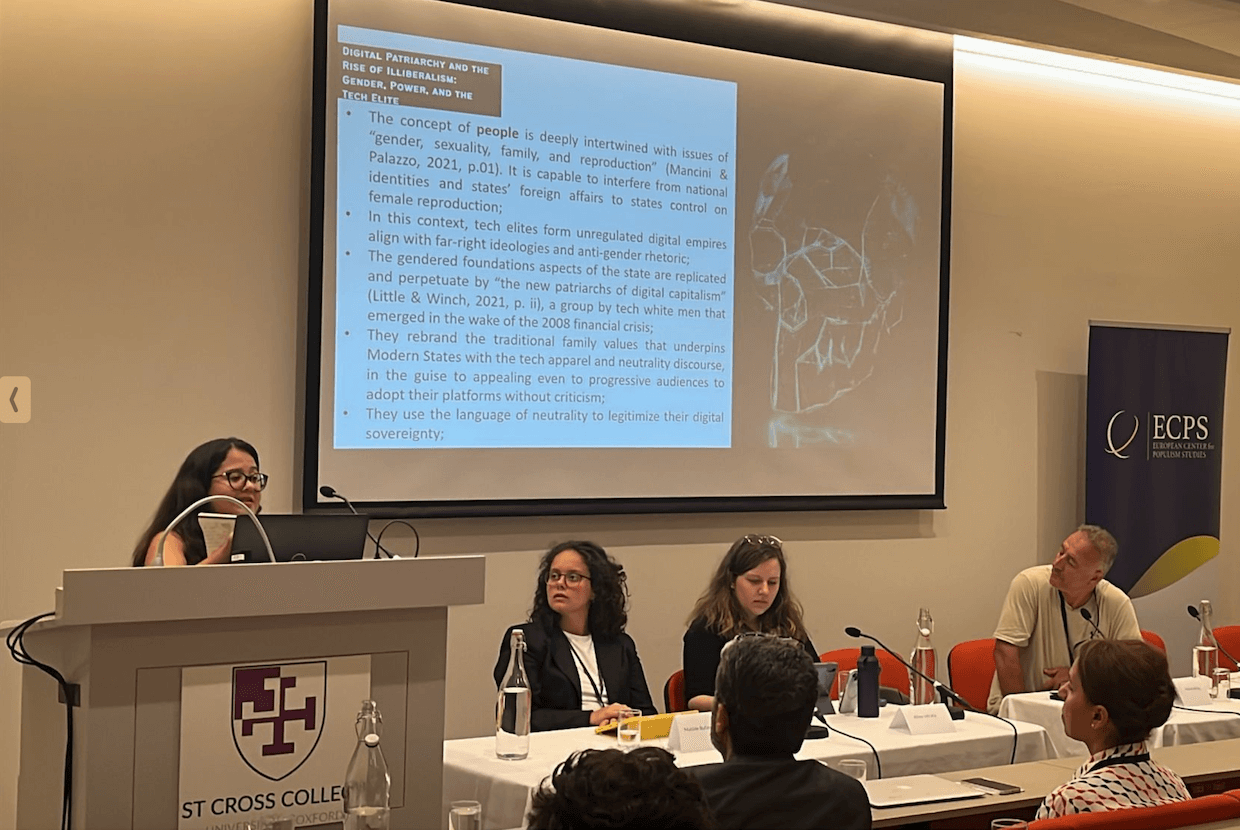

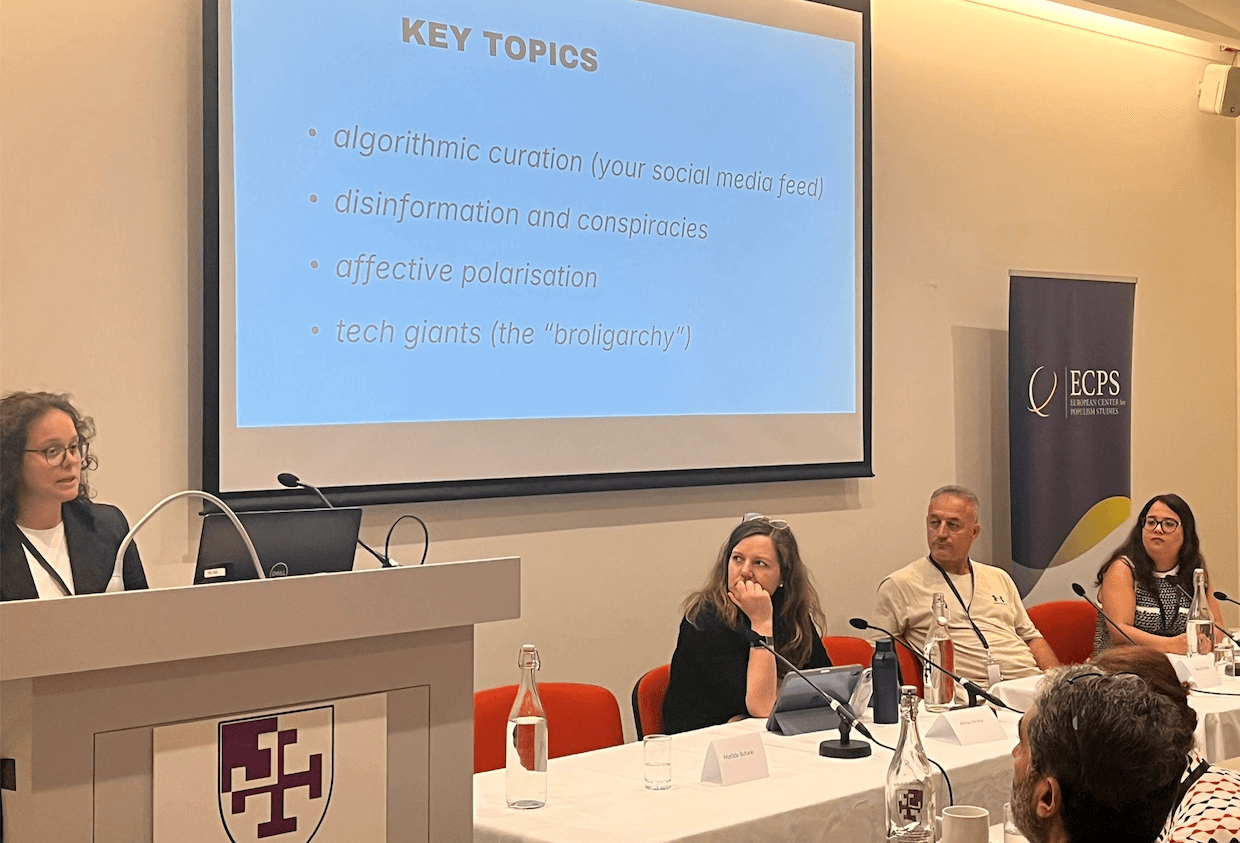

As part of the ECPS International Conference 2025, titled “We, the People” and the Future of Democracy: Interdisciplinary Approaches, held from July 1–3 at St Cross College, University of Oxford, Panel VIII explored the contentious and evolving dynamic between “the people” and “the elite” in global political discourse. The session, titled “The People” vs “The Elite”: A New Global Order?, investigated the ideological and institutional transformations underway as populist movements reframe public authority, challenge established elites, and redefine democratic legitimacy across diverse national contexts.

This panel was co-chaired by Dr. Ashley Wright, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Minerva Global Security Programme, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford, and Dr. Azize Sargın, Director of External Relations at ECPS. Their combined academic and practical expertise provided critical framing and continuity across the session.

The panel featured four intellectually rich presentations. Dr. Aviezer Tucker, Director of the Centre for Philosophy of Historiography and the Historical Sciences (University of Ostrava), opened with “We: The Populist Elites,” offering a provocative take on how contemporary populist leaders paradoxically assume elite roles while railing against elitism. Next, Dr. Pınar Dokumacı (University College Dublin) presented “Reclamations of ‘We, the People’,” reframing civil society in Turkey as a relational and spatial practice of democratic resistance under authoritarian populism.

In a transatlantic frame, Dr. Attila Antal (Eötvös Loránd University) delivered “The Transatlantic Network of Authoritarian Populism,” tracing how Schmittian legal theory and the rise of executive authority underpin political convergence between Trumpism and Orbánism. Closing the session, Professor Murat Aktaş (Muş Alparslan University) introduced their ongoing research in “The French New Right and Its Impact on European Democracies,” unpacking the metapolitical strategies and ideological currents that have shaped the European far-right.

The panel concluded with incisive commentary from Professor Karen Horn (University of Erfurt), who offered thoughtful critiques of transmission mechanisms, intellectual genealogies, and the limits of rationalist paradigms in explaining populist ascendancy.

Together, the session demonstrated how populism’s global diffusion and elite contestation demand renewed theoretical and practical engagement with the future of democratic governance.

Aviezer Tucker: “We: The Populist Elites”

In a characteristically provocative and intellectually agile presentation, Dr. Aviezer Tucker—Director of the Centre for Philosophy of Historiography and the Historical Sciences at the University of Ostrava—challenged the foundational assumptions of contemporary populism scholarship. Speaking during Panel 8 of the ECPS Conference at Oxford, titled “We: The Populist Elites,” Dr. Tucker proposed a contrarian interpretation: that populism is not fundamentally a revolt of “the people” against elites, but a pathology of the elites themselves—a performance of political passions rather than a rational movement for justice or equality.

Dr. Tucker’s opening salvo was clear: the dominant academic consensus, which casts populism as a bottom-up, anti-elite uprising, is analytically flawed. According to Dr. Tucker, this perspective is both too broad and too narrow. It is too broad because resentment against elites is not exclusive to populism—it animates religious reformers, anti-colonialists, and even frustrated HR departments. It is too narrow because the leading figures of modern populist movements are not representatives of the marginalized; they are often extremely wealthy, famous, or already embedded in traditional elite structures. Figures like Trump, Berlusconi, and Orbán are not outsiders—they are elite actors who weaponize public resentment and channel it through affective spectacle.

Instead of viewing populism as an ideology or economic protest, Dr. Tucker reframed it as the rule of political passion, echoing ancient Greek political philosophy and Roman historical precedent. Passion, in his schema, contrasts with interest and reason. Populism, he argued, is fueled by passions that are volatile, self-destructive, and insatiable. In a vivid metaphor, Dr. Tucker likened passions to the emotional chaos of discovering infidelity: a desire to act impulsively (passion), versus a calculated strategy for self-interest (interest), versus a reasoned dialogue on consequences (reason). Where democracy ideally mediates between these levels of response, populism thrives on the first—on raw, unregulated emotionality.

For Dr. Tucker, the true antagonist of populism is not democracy, but technocracy. Technocracy, as the rule of reason and deliberative institutions, represents the control of passions through procedural rationality. Populism, conversely, bypasses this rational architecture. It is not anti-elite per se, but anti-technocratic—waging war on the very mechanisms that enable stability, compromise, and fact-based governance.

Central to Dr. Tucker’s thesis is the insight that populist leaders lack what philosopher Harry Frankfurt called “second-order volitions”—that is, the capacity to willfully regulate their own desires. Populist governance does not structure competing interests or prioritize goals. Instead, it lurches from one outrage to the next, managing public passions not by resolution, but by distraction. Here, Dr. Tucker invoked the “dead cat” strategy: when a leader faces scrutiny or failure, they simply introduce a more sensational narrative—metaphorically placing a dead cat on the table—to hijack the public’s attention.

Crucially, Dr. Tucker argued that truth within populist regimes is emotivist. It corresponds not with reality but with the intensity of passion. The more emotionally charged a claim, the more “authentic” it appears. Hence, the bizarre durability of conspiracies like “Pizzagate,” in which Hillary Clinton was alleged to be running a child trafficking ring out of a pizzeria. These myths resonate not because they are plausible, but because they channel rage into vivid, emotionally satisfying narratives. Dr. Tucker likened these to ancient Roman slanders—emperor-satirizing tales of incest and debauchery—designed not to inform, but to enflame.

Populist storytelling, then, is myth-making: an emotionally driven narrative logic that sacrifices truth for catharsis. Such stories express a collective affect more than a collective will. And in this system, the elite are not immune. Dr. Tucker provocatively claimed that today’s populist elites—whether in Slovakia, the United States, or ancient Athens—are themselves subjects of passion, as self-destructive as the masses they claim to represent.

Drawing from classical history, Dr. Tucker compared modern populists to Athenian figures like Cleon and Cleophon, whom he described as “the Trumps of their time.” These figures, Dr. Tucker noted, embodied the self-defeating tendencies of unrestrained democratic passion. Ancient Athens’ descent into ruin during the Peloponnesian War, he argued, was a case study in populism’s dangers: an emotional, irrational polity tearing itself apart in pursuit of honor and vengeance. For Dr. Tucker, this ancient warning still applies. The Founding Fathers of the United States, aware of Athens’ fate, designed constitutional safeguards to prevent such destruction. But today, we are witnessing a return to those classical dangers—where elite passions destabilize the very democratic systems they inhabit.

Dr. Tucker also turned his critique inward, targeting academic rationalizations of populism. He accused scholars—particularly rational choice theorists—of forcing populist behavior into models of reason and utility that fundamentally misunderstand its nature. Populism is not confused socialism or distorted egalitarianism; it is not an error to be corrected by intellectuals. Rather, it is an elite-led phenomenon, fueled by resentment, vanity, and the deliberate erosion of rational order. The aspiration to explain populism through a technocratic lens, Dr. Tucker argued, only masks the self-destructive tendencies of elite actors who block social mobility and then blame minorities or foreign enemies for the resulting discontent.

In a particularly striking moment, Dr. Tucker insisted, “We are the populist elites.” This “we” was not rhetorical—it was directed at the very academics, policymakers, and educated elites who, through action or inaction, perpetuate the conditions of populism. He called for introspection: Why do we block social mobility? Why do we fear pluralism? Why do we rationalize the irrational? Dr. Tucker concluded with an urgent plea to break this cycle of elite self-destruction—not through more rationalization, but by addressing the structural and psychological drivers of populist passion.

In sum, Dr. Tucker’s presentation offered a deeply original and philosophically grounded theory of populism—not as the voice of the voiceless, but as a destructive performance of elite passions masquerading as popular will. His analysis reinvigorated classical political philosophy to illuminate a profoundly contemporary crisis, urging both intellectual honesty and institutional reform in the face of democracy’s emotive unmaking.

Pınar Dokumacı: Reclamations of ‘We, the People’ — Rethinking Civil Society through Spatial Contestations in Turkey

In her co-authored presentation with Dr. Özlem Aslan, Dr. Pınar Dokumacı, Assistant Professor at the School of Politics and International Relations at University College Dublin, delivered a nuanced and theoretically rich analysis of how civil society in contemporary Turkey is being reimagined through embodied, spatial acts of contestation. Speaking during Panel 8 of the ECPS Conference 2025 at Oxford University, Dr. Dokumacı sought to move beyond institutional and deliberative conceptions of civil society by foregrounding the generative political agency that emerges from public space reclamations. Drawing on three distinct case studies—protests in Istanbul’s Taksim Square, courtroom mobilizations around Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, and the ongoing silent protests at Boğaziçi University—Dr. Dokumacı proposed a re-theorization of civil society as a lived, relational, and care-centered practice.

Framed against the backdrop of Turkey’s slide into authoritarian populism under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) since 2002, the presentation contended that civil society in Turkey has not simply been suppressed or evacuated, but rearticulated through spatial dissent. The AKP, especially under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has transformed its initial majoritarian populist platform into a hegemonic regime that narrows the meaning of “the people” to a singular, conservative, Sunni-nationalist subject. In doing so, it has eroded formal political arenas such as the media, judiciary, and higher education, collapsing the distinction between state and ruling party while marginalizing dissenting voices as traitorous. Yet, rather than yielding to this closure, Turkish citizens have responded by enacting politics outside official channels—through occupation, performance, and co-presence in public spaces.

Dr. Dokumacı introduced the notion of “spatial contestation” as a conceptual anchor for analyzing these dynamics. She drew from theorists like Paul Routledge and Jacques Rancière to argue that public space is not a neutral backdrop for politics but is co-produced through collective action. For Routledge, space is not a container but a process, and for Rancière, politics is the interruption of the sensible order by those who have no recognized part in it. In Turkey, such spatial interventions challenge the state’s attempt to monopolize public legitimacy and rewrite “the people” as a homogenous body. By reclaiming space, participants assert alternative identities and visions of political community.

The first empirical case examined the repeated attempts by feminist, LGBTQI+, and labor groups to reclaim Taksim Square, a historically symbolic site of democratic contestation, especially since the 2013 Gezi Park protests. Despite routine bans, heavy policing, and arrests, demonstrators return to Taksim on key dates such as March 8 (International Women’s Day), May 1 (Labor Day), and during Pride marches. What matters, Dr. Dokumacı emphasized, is not merely the content of the slogans but the manner of collective engagement: protestors coordinate routes via encrypted messaging apps, walk with strangers for safety, and care for each other during and after detainment. These acts of mutual support and bodily co-presence enact a form of “chosen community,” grounded not in fixed identity or institutional membership, but in relational care and democratic commitment. Civil society here is not deliberative in the Habermasian sense, but performative and affective—built through risk, solidarity, and resistance.

The second case centered on the transformation of courtrooms into contested political spaces following Turkey’s 2021 withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention. In protest, hundreds of women from diverse cities such as Mersin, Adana, and Eskişehir traveled to Ankara to attend public hearings, where many were initially barred entry. Refusing to leave, they chanted, pressed against barriers, and asserted their right to visibility and voice within the legal apparatus. The courtroom, typically a site of state authority and procedural rationality, was reappropriated as a space of embodied dissent. Here, care again emerged as central—not as sentimentality but as democratic praxis. Women attended together, protected one another, and jointly confronted an institutional order that sought to render them passive objects of governance. Their protest was less about abstract legal rights than about reasserting agency, collectivity, and civic presence.

The final example focused on the ongoing silent protests at Boğaziçi University, where faculty, students, and alumni have opposed the government’s appointment of a rector without internal consultation since early 2021. Each day at 12:15 PM, faculty members gather in their academic regalia and silently turn their backs to the rector’s office. This silent, disciplined, and highly symbolic act reclaims the university as a moral and intellectual commons. The protest, now in its third year, has become a ritual of care and resistance: legal support is coordinated, persecuted students are assisted, and resources are pooled. As with the other cases, care here is not private or domestic, but associational and political. It sustains protest not through charisma or media spectacle, but through daily, durable acts of support and mutual responsibility.

Across all three examples, Dr. Dokumacı identifies a shared political logic: the reclamation of public space not only as resistance but as world-building. Spatial contestations do not merely oppose authoritarianism; they prefigure alternative civilities—plural, interdependent, and grounded in care. The authors draw extensively on feminist political theory, particularly the work of Iris Marion Young, Carole Pateman, Anne Phillips, and Ella Myers, to argue that mainstream liberal notions of civil society often erase dependency, embodiment, and affect. By contrast, these Turkish cases exemplify what Myers calls “worldly ethics”—a form of care rooted in engagement with the world as it is, rather than ideal abstractions. Inspired by Hannah Arendt’s amor mundi, worldly ethics emphasizes political responsibility as intersubjective, collective, and contingent.

For Dokumacı, the civil society that emerges from these spatial contestations is not an intermediary domain between state and market, nor a rational sphere of disembodied discourse. It is a lived, agonistic terrain forged through vulnerability, presence, and care. Civil society, in this sense, is not something one has, but something one does—together, in the streets, in courtrooms, and on campuses. It is enacted through relational practices that challenge singularity with plurality, repression with expression, and authoritarian isolation with democratic interdependence.

In sum, Dr. Dokumacı’s presentation offered a powerful rethinking of civil society in contexts of authoritarian populism. Rather than mourn the hollowing of institutional politics, she invited scholars to look where politics has migrated—to the margins, to the bodies in motion, to the everyday ethics of solidarity and care. These practices may not deliver immediate policy outcomes, but they perform democracy in its most elemental form: as shared risk, shared presence, and shared commitment to a plural political world.

Attila Antal: The Transatlantic Network of Authoritarian Populism — The Rise of the Executive and Its Dangers to Democracy

At the ECPS Conference 2025 in Oxford, Dr. Attila Antal, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law and Institute of Political Science, Eötvös Loránd University, delivered a compelling and richly contextualized presentation on the growing international convergence between authoritarian populist movements, particularly focusing on Hungary and the United States. His presentation, “The Transatlantic Network of Authoritarian Populism: The Rise of the Executive and Its Dangers to Democracy,” dissected the ideological, institutional, and legal interdependencies that bind contemporary right-wing populisms across the Atlantic, with special emphasis on the centralization of executive power.

Drawing from his broader research project on authoritarian legality and constitutional transformation in Hungary, Dr. Antal argued that what we are witnessing today is not merely a domestic authoritarian drift, but a coherent, transnational strategy to reshape democratic norms. This strategy, he contended, is undergirded by an ideological framework that combines neo-Schmittian legal theory, the “unitary executive” doctrine from the US, and Gramscian tactics of intellectual hegemony. Together, these elements form what Dr. Antal referred to as a transatlantic authoritarian-populist epistemic and institutional network, with Viktor Orbán’s Hungary and Donald Trump’s America serving as its key nodes.

Dr. Antal began by challenging the assumption that nationalism and internationalism are mutually exclusive. On the contrary, he insisted, nationalist populist movements are increasingly coordinated at the international level. While the 20th century saw the internationalization of leftist ideologies—such as communism—what we observe today is the globalization of right-wing populism. This is not an accidental development, Dr. Antal stressed, but one with deep ideological roots in Carl Schmitt’s vision of unchecked executive sovereignty and in American conservative legal theory’s interpretation of presidential power.

At the core of this new populist consensus, Dr. Antal posited, lies the erosion of liberal constitutionalism and the consolidation of executive power. In Hungary, this process has been driven by what he termed neo-Schmittian authoritarian legality: the production of laws that serve autocratic ends while maintaining a veneer of legality. This legalistic authoritarianism, Dr. Antal argued, mimics constitutional form while hollowing out its liberal-democratic content. Echoing Schmitt’s infamous formulation that the sovereign is he who decides on the exception, Orbán’s regime has normalized states of exception—often justified by crises like migration or war—to expand executive discretion.

Dr. Antal connected this legal-political logic to the US context through the lens of the unitary executive theory—a doctrine that gained traction in conservative legal circles following Morrison v. Olson and was championed by figures such as the late Justice Antonin Scalia. The theory holds that all executive power is vested solely in the president, thereby legitimating the subordination of other branches of government, including the judiciary and administrative agencies. While the doctrine itself is rooted in American constitutional debate, Antal illustrated how its ideological logic has been imported into Hungary through what he called a process of ideological translation. For example, Hungary’s insistence on “national constitutional identity” in its disputes with the European Union mirrors American assertions of executive sovereignty and legal exceptionalism.

Beyond legal theory, Dr. Antal explored how this transatlantic populist project is being institutionally embedded. He focused on three dimensions: policy coordination, lobbying infrastructure, and intellectual hegemony.

First, on the level of policy and ideological coordination, Dr. Antal noted the mutual admiration and collaboration between Orbán and Trump. Orbán famously declared, “We were Trump before Trump,” emphasizing Hungary’s pioneering role in the right-wing populist agenda. This relationship has been institutionalized through venues such as CPAC (Conservative Political Action Conference), which Hungary has hosted multiple times. These events serve not only as symbolic affirmations of ideological alignment but also as platforms for policy and strategic exchange.

Second, Dr. Antal examined the lobbying apparatus that has been cultivated by the Orbán regime within the United States. Under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), Hungary now sponsors a sizable and professionally structured lobbying network in Washington, D.C., including institutions such as the Hungarian Foundation, the American-Hungarian Federation, and the Hungary-American Coalition. These organizations operate both formally and informally, leveraging diaspora connections and political patronage to promote Hungary’s illiberal model. According to Dr. Antal, this lobbying machine is financed with Hungarian taxpayer money and has become increasingly adept at penetrating elite conservative circles in the US.

Third, and perhaps most strikingly, Dr. Antal underscored the importance of intellectual infrastructure and ideological production. Drawing from a Gramscian framework, he argued that Orbán’s regime has made significant investments in cultivating a transnational right-wing intellectual class. Institutions like the Center for Fundamental Rights and Mathias Corvinus Collegium serve as think tanks, training centers, and propaganda hubs. These organizations fund visiting fellowships and public events that platform conservative figures such as Rod Dreher, a key intermediary with connections to US political elites, including the Vice President. Through these means, Hungary exports its ideological model while shaping public discourse around nationalism, traditionalism, and executive supremacy.

Dr. Antal’s presentation concluded with a reflection on the global implications of this authoritarian-populist network. The convergence of legal doctrines (neo-Schmittianism and unitary executive theory), institutional tactics (states of emergency and constitutional identity claims), and ideological narratives (the “real people” versus global elites) points to a reconfiguration of the democratic order. These are not isolated developments, Dr. Antal warned, but part of a coordinated backlash against liberal democratic norms across the Atlantic.

He emphasized that this backlash is being operationalized through sophisticated networks of lobbying, intellectual exchange, and institutional mimicry. The danger lies not just in the erosion of checks and balances within individual states, but in the global diffusion of illiberalism. What makes this movement powerful, Dr. Antal suggested, is not its crude authoritarianism but its strategic adaptation of democratic and legal language to authoritarian ends.

In sum, Dr. Antal’s presentation offered a sobering diagnosis of a new authoritarian internationalism—one that harnesses nationalism, exploits legal structures, and instrumentalizes executive power across borders. As liberal democracies grapple with internal vulnerabilities, the transatlantic alliance between Trumpism and Orbánism signals a profound and organized challenge to constitutional democracy itself.

Murat Aktaş: The French New Right and Its Impact on European Democracies

In his thought-provoking presentation titled “The French New Right and Its Impact on European Democracies,”Professor Murat Aktaş of Muş Alparslan University introduced an emerging research project, co-developed with Dr. Russell Foster of King’s College London, which seeks to assess the ideological influence of the French Nouvelle Droite (New Right) on the political strategies of contemporary radical right and populist parties across Europe. Professor Aktaş outlined the genealogy, strategic frameworks, and transnational dissemination of the French New Right’s ideas—especially its metapolitical tactics—and explored how these have subtly but significantly transformed European political landscapes.

Professor Aktaş began by clarifying the conceptual ambiguities surrounding the term “New Right,” noting that it holds divergent meanings in different national contexts. In the Anglo-American and Turkish settings, for instance, the “New Right” typically refers to the economically neoliberal, anti-statist programs of Thatcher, Reagan, or Turgut Özal. By contrast, the French New Right—rooted in the intellectual and cultural strategies of Alain de Benoist and the Groupement de recherche et d’études pour la civilisation européenne (GRECE), established in the late 1960s—eschews economic liberalism and electoral politics in favor of long-term cultural and ideological transformation. Its mission is to reconstruct European identity on exclusionary, ethno-cultural foundations, deploying the tools of cultural hegemony and metapolitics, concepts borrowed and reconfigured from Antonio Gramsci’s Marxist theory.

The French New Right, Professor Aktaş explained, emerged in the wake of World War II and the delegitimization of biological racism and fascist ideology. Intellectuals like de Benoist responded by recasting far-right ideology through the language of cultural difference rather than racial superiority. Rather than promoting direct political action, they advocated reshaping cultural and intellectual life—education, media, and public discourse—through metapolitical means to make society more receptive to far-right values. Their aim was not simply to win elections, but to control the terms of debate about identity, civilization, and sovereignty.

Crucially, Professor Aktaş emphasized that the French New Right has had a disproportionate yet under-examined impact on political parties and movements throughout Europe. From Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS) Party, Hungary’s Fidesz, and Italy’s Brothers of Italy, to older parties like Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ), the ideological DNA of the Nouvelle Droite can be traced in their discourses, strategies, and political architectures. In each case, the metapolitical strategy—prioritizing culture, identity, and symbolic power over policy detail—has been instrumental in transforming radical ideas into political mainstreams.

Through detailed case studies, Professor Aktaş illustrated how this intellectual framework has adapted to national contexts:

In Poland, the PiS government drew on French New Right strategies to reshape legal and political institutions in a nationalist and socially conservative direction. Despite EU membership, PiS reinterpreted national sovereignty through the lens of cultural homogeneity and civilizational defense, positioning itself against “liberal decadence” and immigration, echoing de Benoist’s themes. Jarosław Kaczyński and his allies also maintained a paradoxical alliance with the Catholic Church, despite the French New Right’s historical critique of Christianity as a source of universalism and egalitarianism.

In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz exemplifies the most successful application of Nouvelle Droite strategy. Since 2010, Orbán has systematically restructured Hungary’s constitutional framework, media landscape, and academic institutions. Drawing on metapolitics, Orbán presents his model as an illiberal democracy rooted in national values and historical destiny. Like the French New Right, Orbán opposes globalism, multiculturalism, and American-style liberalism, yet maintains tactical alliances with US conservative elites, including Donald Trump.

In Italy, the Brothers of Italy and associated movements like CasaPound explicitly borrowed French New Right rhetoric and aesthetics. As Professor Aktaş noted, Italian far-right intellectuals translated de Benoist’s works and established journals and publishing houses to popularize his ideas. Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s cultural agenda, which emphasizes tradition, family, and national identity, reflects this intellectual heritage—despite the seeming contradiction between Catholicism’s universalism and the New Right’s pagan or Greco-Roman civilizational narratives.

One of the most striking aspects of Professor Aktaş’s presentation was his discussion of paradoxes within this ideological exportation. The Nouvelle Droite originally rejected Christianity, the American-led international order, and supranational institutions like the EU. Yet in many countries, its ideological offspring have formed strategic alliances with the Church, embraced US conservative figures such as Donald Trump, and pursued Eurosceptic yet integrationist policies when convenient. As Professor Aktaş cleverly observed, the French New Right adapts “like water,” molding itself to local cultural and institutional configurations while retaining its core metapolitical logic.

Professor Aktaş also highlighted how Nouvelle Droite-inspired parties legitimize anti-immigrant policies not through overt racism, but through arguments about cultural incompatibility and the right to difference. Here, again, the focus is less on biological essentialism and more on defending “European civilization” against perceived internal and external threats—a rhetorical move that normalizes exclusion while avoiding overt fascist associations.

In his conclusion, Professor Aktaş argued that the French New Right’s greatest success lies in its ability to provide an intellectual and strategic roadmap for a post-liberal, exclusionary political order. Its legacy is not only visible in the programs of radical right parties, but also in the gradual adoption of its narratives by mainstream conservative and even centrist actors. The presentation thus called for renewed scholarly attention to metapolitical movements and cultural strategies that operate beneath the surface of electoral politics. Rather than focusing solely on populism as style or demagoguery, Professor Aktaş urged participants to understand the slow, structural transformation of liberal democracy facilitated by ideas that were once confined to the margins.

The project, still in its early stages, promises to shed light on the intellectual circulations and ideological infrastructures sustaining Europe’s contemporary populist right. By tracking how the Nouvelle Droite’s doctrines mutate across borders—reconciling paganism with Catholicism, ethnonationalism with transatlanticism, and anti-liberalism with electoral legitimacy— Professor Aktaş opens a critical window into the metapolitical undercurrents shaping 21st-century European democracy.

Assessments by Panel Discussant Karen Horn

Serving as the discussant for the final panel of the ECPS Conference 2025 at St Cross College, Oxford University, Professor Karen Horn offered a nuanced, intellectually generous, and analytically rigorous set of reflections on the four presentations in Panel 8. Her assessment, structured in reverse order of presentation, illuminated both the strengths and tensions in the authors’ arguments, while advancing key meta-level concerns regarding method, conceptual clarity, and the normative stakes of democratic theory in the face of authoritarian populism.

Horn began with Professor Murat Aktaş’s presentation on “The French New Right and Its Impact on European Democracies.”Acknowledging the empirical richness of the paper and Professor Aktaş’s deep familiarity with the ideological legacy of the Nouvelle Droite, Professor Horn lauded the contribution for tracing the diffusion of Alain de Benoist’s ideas across national borders. However, she pressed for greater specificity regarding the mechanisms of transmission: Who are the concrete actors—translators, intellectuals, party strategists—who helped implant French New Right ideology into other political contexts such as Poland, Hungary, and Italy? Do current political elites directly reference de Benoist, or have his ideas simply “seeped” into the broader ideological ether? Professor Horn noted that such questions about the Overton window—how fringe ideas become part of mainstream political discourse—are central to understanding the New Right’s metapolitical success. She further questioned whether the stark national distinctions in intellectual traditions may now be outdated, given the increasingly transnational nature of ideological exchange in Europe.

Transitioning to Dr. Attila Antal’s paper on “The Transatlantic Network of Authoritarian Populism,” Horn praised the ambitious mapping of how Orbánism and Trumpism draw upon a shared neo-Schmittian legal-political framework, particularly in their conceptualization of unrestrained executive power. Still, she raised important questions regarding attribution: Do Viktor Orbán or Donald Trump explicitly cite Carl Schmitt, or are these structural resemblances inferred retrospectively by scholars? Professor Horn warned of the risk of post hoc intellectual genealogy—attributing theoretical lineage where actors themselves may be unaware or disinterested in such foundations. In terms of method, she commended the use of network analysis but cautioned against reifying actors as static nodes. Populist leaders, she noted, often undergo ideological transformations—Orbán himself was once a liberal democrat—and network analysis should remain sensitive to such temporal evolution.

In her response to Dr. Pınar Dokumacı’s feminist-ethnographic presentation on spatial contestations in Turkey, Professor Horn expressed admiration for the paper’s conceptual breadth, including its engagement with civil society as relational care, drawn from feminist political theory. She appreciated the rethinking of public space—not merely as a site of protest, but as an embodied terrain of ethical engagement. However, she flagged a potential straw man in the depiction of traditional political theory as uniformly neoliberal, rationalist, and male-coded. Drawing from her own discipline of economics, Professor Horn reminded the audience that even canonical thinkers like Adam Smith—often caricatured as the father of homo economicus—attended deeply to human sympathy and moral sentiments. In short, while endorsing Dr. Dokumacı’s relational theory of protest, Professor Horn encouraged the authors to moderate their opposition by recognizing existing complexity in mainstream theory.

Professor Horn also challenged the authors to consider a crucial empirical question: When does civil resistance succeed? While spatial contestations may be “transformative” in the consciousness of participants, at what point do they become transformative in institutional or regime terms? Using Belarus as a counter-example—where mass protests were brutally suppressed—she invited reflection on the thresholds of efficacy: when does relational care and presence in public space translate into political change? What conditions make civil protest merely symbolic, and when can it truly destabilize authoritarian regimes?

Finally, Professor Horn addressed the first presentation, which advanced a philosophical reconsideration of populism by shifting from strictly rationalist frames to more passion-inflected understandings of political subjectivity. While appreciating the attempt to move beyond over-rationalized models of political agency, she expressed caution about rejecting rationalism outright. Citing the long history of economic theory’s empirical self-correction—from the ideal of homo economicus to models incorporating altruism, reciprocity, and bounded rationality— Professor Horn argued that reason and passion need not be mutually exclusive. She invoked David Hume’s dictum that reason is the slave of the passions but also referenced Adam Smith’s impartial spectator as a mediating force between reason and emotion. This dialectical tension, she suggested, offers a more fruitful avenue for thinking about populist mobilization than an outright retreat from rationalism.

Toward the end of her remarks, Professor Horn homed in on the most politically urgent dimension of the panel: the self-destructiveness of populist movements. Several papers alluded to the internal contradictions of populist regimes—that their reliance on crisis, polarization, and unchecked executive power ultimately undermines their own legitimacy and governance capacity. Professor Horn asked, provocatively: Does this contain a seed of hope? Will populism collapse under its own weight? And if so, at what cost? Will the institutions of liberal democracy survive the implosion? Her closing note thus combined analytical clarity with a sobering ethical reflection: understanding populism is not only an academic imperative, but a moral one. The challenge, she emphasized, is to grasp the deep cultural and affective appeals of authoritarian populism without surrendering to its logic—and to resist being dragged down in its self-destructive spiral.

In sum, Professor Karen Horn’s discussant intervention served as a masterclass in interdisciplinary engagement. Moving fluidly between political theory, economics, intellectual history, and methodology, she demonstrated the value of critical synthesis across academic domains. Her questions did not aim to dismantle the papers but to strengthen them by pushing for deeper conceptual specificity, empirical grounding, and reflexivity. At a conference devoted to the future of democracy, Professor Horn reminded the audience that democracy’s defense requires not only resistance on the ground but intellectual precision in the realm of ideas.

Conclusion

Panel 8 of the ECPS International Conference 2025, “The People” vs “The Elite”: A New Global Order?, offered a compelling and multifaceted interrogation of how populist and authoritarian currents are reshaping the conceptual boundaries between power and people, passion and reason, resistance and complicity. The panel brought together critical voices from political theory, legal studies, feminist scholarship, and intellectual history.

The presentations revealed a global pattern in which populist leaders, while claiming to represent “the people,” increasingly operate as elite actors who weaponize emotional narratives, co-opt civil institutions, and hollow out democratic norms from within. Whether through the emotivist spectacles of populist elites (Tucker), the embodied spatial politics of feminist resistance (Dokumacı), the transnational architecture of executive overreach (Antal), or the metapolitical ambitions of the French New Right (Aktaş), each contribution exposed how democratic backsliding is no longer a deviation but a structural strategy.

Professor Karen Horn’s incisive commentary amplified these insights by questioning the theoretical assumptions underpinning populist discourse and highlighting the need for conceptual precision, empirical humility, and normative vigilance. Her final provocation—that populism’s self-destructive tendencies may ultimately implode—raised a sobering ethical dilemma: can liberal democracy survive the wreckage?

In sum, Panel 8 demonstrated that the populist challenge is neither local nor ephemeral. It is a sustained ideological project that must be met with intellectual rigor, civic imagination, and transnational solidarity. Democracy, as the panel affirmed, is not a settled order—but a continuous struggle over meaning, power, and the people themselves.

Note: To experience the panel’s dynamic and thought-provoking Q&A session, we encourage you to watch the full video recording above.