Virtual Programme: September 4, 2025 – April 16, 2026 via Zoom

Between 2012 and 2024, one-fifth of the world’s democracies disappeared. During this period, “us vs. them” rhetoric and divisive politics have significantly eroded social cohesion. Yet in some instances, democracy has shown remarkable resilience. A key factor in both the rise and decline of liberal democracies is the use—and misuse—of the concept of “the people.” This idea can either unify civil society or deepen social divisions by setting “the people” against “the others.” This dichotomy lies at the heart of populism studies. However, the conditions under which “the people” become a force for democratization or a tool for majoritarian oppression require deeper, comparative, and interdisciplinary analysis. Understanding this dynamic is crucial, as it has profound implications for the future of democracy worldwide. This programme aims to foster a broad and interdisciplinary dialogue on the challenges of democratic backsliding and the pathways to resilience, with a focus on the transatlantic space and global Europe. It aims to bring together scholars from the humanities, arts, social sciences, and policy research to explore these critical issues.

Organiser

European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS)

Partners

The Humanities Division, Oxford University

Rothermere American Institute

Oxford Network of Peace Studies (OxPeace)

European Studies Centre, St Antony’s College, Oxford University

Oxford Democracy Network

Special thanks to Phil Taylor, Pádraig O’Connor, Freya Johnston, Heidi Hart, David J. Sanders, Clare Woodford, Anthony Gardner, Liz Carmichael, Harry Bregazzi, Hugo Bonin, Benjamin Gladstone, Doris Suchet, Jenny Davies, Justine Shepperson, Daniel Rowe, Katy Long, Julie Adams, Réka Koleszar, Stella Schade, Louise Lok Yi Horner, Jacinta Evans, Contestation of the Liberal Script (SCRIPTS), Network for Constitutional Economics and Social Philosophy (NOUS), and Centre for Applied Philosophy, Politics and Ethics (CAPPE).

Session 1

The Rise of Populist Authoritarianism around the World

Date/Time: Thursday, September 4, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Oscar Mazzoleni (Professor, Political Science, University of Lausanne; Editor-in-Chief, Populism & Politics).

Introduction

David J. Sanders (Regius Professor of Political Science, University of Essex, Emeritus).

Speakers

“The Rise of Populist Authoritarianism in India and the US: Do Family Dynasties and Big Businesses Really Control Democracy?” by Dinesh Sharma, Shoshana Baraschi-Ehrlich, Britt Romagna, Ms. Ayako Kiyota (Fordham University, NYC), Amartya Sharma (Student, George Washington University, D.C.)

“Out-groups and Elite Cues: How Populists shape Public Opinion,” by Michael Makara (Associate Professor of Comparative Politics and International Relations, University of Central Missouri) and Gregory W. Streich (Professor of Political Science and Chair of the School of Social Sciences and Languages, University of Central Missouri).

“From Economic to Political Catastrophe: Four Case Studies in Populism,” by Akis Kalaitzidis, (Professor of Political Science, Department of Government, Law, and International Studies, University of Central Missouri).

“Populism, Clientelism, and the Greek State under Papandreou,” by Elizabeth Kosmetatou (Professor of History, University of Illinois Springfield) and Akis Kalaitzidis (Professor of Political Science, Department of Government, Law, and International Studies, University of Central Missouri).

Discussant

João Ferreira Dias (Researcher at the International Studies Centre of ISCTE, in the Research Group Institutions, Governance and International Relations).

Session 2

The ‘Nation’ or just an ‘Accidental Society’: Identity, Polarization, Rule of Law and Human Rights in 1989-2025 Poland

Date/Time: Thursday, September 18, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Speakers

“Varieties of Polish Patriotism: Experience of “Solidarity” 1980-1989 in Context of History and Anthropology of Ideas,” by

Joanna Kurczewska (Professor in the humanities, Head of the Sociology and Anthropology of Culture Team at the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences).

“

Single Text, Clashing Meanings: Political Polarization, Constitutional Axiology and the Polish Constitutional Quagmire,” by

Kamil Jonski (Economist, PhD in law at the University of Lodz).

“Protection of Human Rights and Its Implications for Women’s and Minority Rights,” by

Malgorzata Fuszara (Professor of humanities in the field of sociology, Institute of Applied Social Sciences (IASS), University of Warsaw).

“Who Speaks for Whom: The Issue of Representation in the Struggle for the Rule of Law,” by Jacek Kurczewski (Professor of humanities in the field of Sociology, Lecturer at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology of Customs and Law at the University of Warsaw).

Discussants

Magdalena Solska (Assistant Professor, Department of European Studies and Slavic Studies, University of Fribourg).

Barry Sullivan (Professor, Institute For Racial Justice, Loyola University Chicago School of Law).

Krzysztof Motyka (Professor, Institute of Sociological Sciences, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin)

Session 3

Populism, Freedom of Religion and Illiberal Regimes

Date/Time: Thursday, October 2, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Marietta D.C. van der Tol (PhD, Landecker Lecturer, Faculty of Divinity, University of Cambridge; Senior Postdoctoral Researcher, Trinity College)

Speakers

“Religious Freedom as Hungaricum Hungarian iIliberalism and the Political Instrumentalization of Religious Freedom,” by Marc Loustau (PhD., Independent Scholar).

“Religious or Secular Freedom? On Pragmatic Politicization of Religion in Post-socialist Slovakia,” by Juraj Buzalka (Associate Professor of Social Anthropology, Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences at Comenius University).

“Illiberal Theocracy in Texas? The Incorporation of Evangelical Christian Theology into State Law,” by Rev. Dr. Colin Bossen (First Unitarian Universalist of Houston and Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford).

Discussants

Simon P. Watmough (Freelance academic researcher and editor and serves as a non-resident research fellow at ECPS).

Erkan Toguslu (PhD, Researcher at the Institute for Media Studies at KU Leuven, Belgium).

Session 4

Performing the People: Populism, Nativism, and the Politics of Belonging

Date/Time: Thursday, October 16, 2025 – 15:00-17:15 (CET)

Chair

Oscar Mazzoleni (Professor, Political Science, University of Lausanne).

Speakers

“We, the People: Rethinking Governance Through Bottom-Up Approaches,” by Samuel Ngozi Agu (Ph.D., Dean of the MJC Echeruo Faculty of Humanities at Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria).

“Uses and Meanings of ‘the People’ in Service of Populism in Brazil,” by Eleonora Mesquita Ceia (Professor at the National Faculty of Law of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brazil).

“The Idea of ‘People’ Within the Domain of Authoritarian Populism in India,” by Shiveshwar Kundu (Jangipur College, University of Kalyani).

“We, the People: The Populist Subversion of a Universal Ideal,” by Mouli Bentman, Mike Dahan (Sapir College, Israel).

Discussants

Abdelaaziz Elbakkali (Associate Professor of Media and Cultural Anthropology, SMBA University, Fes; Post-Doc Fulbright visiting scholar at Arizona State University).

Azize Sargin (Director for External Affairs, ECPS).

Session 5

Constructing the People: Populist Narratives, National Identity, and Democratic Tensions

Date/Time: Thursday, October 30, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Heidi Hart (PhD, Arts Researcher and Practitioner based in Utah, US and Scandinavia).

Speakers

“The Romanian and Hungarian People in Populist Leaders’ Narratives between 2010-2020,” by Gheorghe Andrei (PhD Student, University of Bucharest and Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris).

“The Application of the Concepts of ‘People’ and ‘Nation’ in Recent Political Developments in Germany: Theoretical Sensitivities and Their Implications for Democracy,” by Yazdan Keikhosrou Doulatyari (Researcher at the Institute of Sociology, Technische Universität Dresden).

“Ripping off the People: Populism of the Fiscally Tight-fist,” by Amir Ali (Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi).

Discussants

Hannah Geddes (PhD Candidate, University of St. Andrews).

Amedeo Varriela (PhD, University of East London).

Session 6

Populism and the Crisis of Representation: Reimagining Democracy in Theory and Practice

Date/Time: Thursday, November 13, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Ilhan Kaya (PhD, Visiting Professor at Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada; Former Professor at Yıldız Technical University in Turkey).

Speakers

“De-Exceptionalizing Democracy: Rethinking Established and Emerging Democracies in an Age of Liberal Backsliding,” by Jonathan Madison (Governance Fellow at the R Street Institute).

“Mobilizing for Disruption: A Sociological Interpretation of the Role of Populism in the Crisis of Democracy,” by João Mauro Gomes Vieira de Carvalho (Member of the Research Committee of Sociological Theory at the International Sociological Association (ISA) and a researcher at LabPol/Unesp and the GEP Critical Theory: Technology, Culture, and Education).

“Daniel Barbu’s and Peter Mair’s Theoretical Perspectives on Post-politics and Post-democracy,” by Andreea Zamfira (Associate Professor with the Department of Political Science, University of Bucharest).

Discussants

Amedeo Varriela (PhD, University of East London).

Amir Ali (PhD, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi).

Session 7

Rethinking Representation in an Age of Populism

Date/Time: Thursday, November 27, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Christopher N. Magno (Associate Professor, Department of Justice Studies and Human Services, Gannon University).

Speakers

“Beyond Fairness: Meritocracy, the Limits of Representation, and the Politics of Populism,” by Elif Başak Ürdem (PhD candidate in political science at Loughborough University).

“Memetic Communication and Populist Discourse: Decoding the Visual Language of Political Polarization,” by Gabriel Bayarri Toscano (Assistant Professor, Department of Audiovisual Communication, Rey Juan Carlos University).

“Paradigms of ‘Popular Sovereignty’: Populism as Part of the Transformative History of the Concept,” by Maria Giorgia Caraceni (PhD Candidate in the History of Political Thought, Guglielmo Marconi University of Rome; Researcher at the Institute of Political Studies San Pio V).

Discussants

Sanne van Oosten (Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Oxford).

Thibaut Dauphin (PhD, Research Associate at the Montesquieu Research Institute, University of Bordeaux).

Session 8

Fractured Democracies: Rhetoric, Repression, and the Populist Turn

Date/Time: Thursday, December 11, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Azize Sargin (Ph.D., Director for External Affairs, ECPS).

Speakers

Charismatic Populism, Suffering, and Saturnalia,” by Paul Joosse (Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Hong Kong).

“The Evolution of the Rhetoric of the “Alternative for Germany”: A Comparative Analysis of the Election Campaigns for the European Parliament in 2019 and 2024,” by Artem Turenko (PhD Candidate, Political Science at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow).

Discussants

Helena Rovamo (Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Eastern Finland).

Jonathan Madison (Governance Fellow at the R Street Institute).

Session 9

Populism, Crime, and the Politics of Exclusion

Date/Time: Thursday, January 8, 2026 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Helen L. Murphey (Post Doctoral Scholar at the Mershon Center for International Security Studies at The Ohio State University).

Speakers

“From Crime Shows to Power: The Rise of Criminal Populism,” by Christopher N. Magno (Associate Professor in the Department of Justice Studies and Human Services at Gannon University).

“The Legitimization Process of the FPÖ’s and the NR’s Migration Policies,” by Russell Foster (Senior Lecturer in British and International Politics at King’s College London, School of Politics & Economics, Department of European & International Studies).

“Anti-Party to Mass Party? Lessons from the Radical Right’s Party Building Model,” by Saga Oskarson Kindstrand (PhD candidate, Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics, Sciences Po).

Discussants

Hannah Geddes (PhD Candidate, University of St. Andrews).

Vlad Surdea-Hernea (Postdoctoral researcher at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna).

Session 10

Resisting the Decline: Democratic Resilience in Authoritarian Times

Date/Time: Thursday, January 22, 2026 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Amedeo Varriela (PhD, University of East London).

Speakers

“Resilience in Market Democracy,” by Peter Rogers (Senior lecturer in Sociology at Macquarie University).

“The Contradictory Challenges of Training Local Elected Officials for the Future of Democracy,” by Pierre Camus (Postdoctoral Fellow, Nantes University).

“The Rise of Women-Led Radical Democracy in Rojava: Global Democratic Decline and Civil Society Resilience Amidst Middle Eastern Authoritarianism,” by Soheila Shahriari (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, (EHESS)).

“Feminist Diaspora Activism from Poland and Turkey: Resisting Authoritarianism, Anti-Gender Politics, and Reimagining Transnational Solidarity in Exile,” by Ecem Nazlı Üçok (PhD Candidate at the Institute of Sociological Studies, Charles University).

Discussants

Gwenaëlle Bauvois (Ph.D., a sociologist based at the University of Helsinki).

Gabriel Bayarri Toscano (Assistant Professor, Department of Audiovisual Communication, Rey Juan Carlos University).

Session 11

Inclusion or Illusion? Narratives of Belonging, Trust, and Democracy in a Polarized Era

Date/Time: Thursday, February 5, 2026 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Andreea Zamfira (Associate Professor with the Department of Political Science, University of Bucharest).

Speakers

“When Identity Politics and Social Justice Procedures Contribute to Populism,” by Saeid Yarmohammadi (University of Montreal).

“Why Do We Trust The DMV? Exploring the Drivers of Institutional Trust in Public-facing Government Agencies,”by Ariel Lam Chan (PhD student in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University).

“Active Citizenship, Democracy and Inclusive Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nexus, Challenges and Prospects for a Sustainable Development,” by Dr Dieudonne Mbarga (Independent Researcher).

“Silenced Voices in a Democratic Dawn: How the Iranian Constitutional Revolutionaries (1905–1906) Weaponized “the People” Against Minorities,” by Ali Ragheb (PhD., University of Tehran).

Discussants

Jennifer Fitzgerald (Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado).

Russell Foster (Senior Lecturer in British and International Politics at King’s College London, School of Politics & Economics, Department of European & International Studies).

Session 12

Decolonizing Democracy: Governance, Identity, and Resistance in the Global South

Date/Time: Thursday, February 19, 2026 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Moderator

Neo Sithole (PhD candidate at the University of Szeged in Hungary).

Speakers

“Africa at the Test of Populism: Identity Mobilisations, Crises of Political Alternation, and the Trial of Democracy,” by Yves Valéry Obame (The University of Bertoua, Global Studies Institute & Geneva Africa Lab) and Salomon Essaga Eteme (The University of Ngaoundéré, Laboratoire camerounais d’études et de recherches sur les sociétés contemporaines (Ceresc)).

“Decolonial Environmentalism and Democracy: A Comparative Study of Resource Governance in Nigeria and the United Kingdom,” by Oludele Mayowa Solaja (Faculty member in the Department of Sociology at Olabisi Onabanjo University) and Mr. Busayo Olakitan Badmos (Postgraduate student in the Department of Sociology at Olabisi Onabanjo University).

“Viral but Powerless? Digital Activism, Political Resistance, and the Struggle for Governance Reform in Kenya, by Dr. Asenath Mwithigah (United States International University-Africa).

Discussants

Dr. Gabriel Cyril Nguijol (Researcher at the National Institute of Cartography (NIC), and lecturer at the Cameroonian Institute of Diplomatic and Strategic Studies (ICEDIS)).

Dr. Edouard Epiphane Yogo (Executive Director and Principal Researcher at the Bureau of Strategic Studies — BESTRAT, Yaoundé, Cameroon).

Session 13

Constructing and Deconstructing the People in Theory and Praxis

Date/Time: Thursday, March 5, 2026 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Leila Aliyeva (Associate of REES, Oxford School for Global and Area Studies (OSGA)).

Speakers

“Reimagining Populism: Ethnic Dynamics and the Construction of ‘the People’ in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” by Jasmin Hasanović (Assistant Professor and researcher at the Department for Political Science at the University of Sarajevo – Faculty of Political Science).

“The Two Peoples: Why Deliberating and Voting don’t Belong Together,” by Théophile Pénigaud (postdoctoral researcher at the ISPS, Yale University).

“Institutionalizing the Assembled People,” by Sixtine Van Outryve (Postdoctoral Researcher, Radboud Universiteit; UCLouvain).

“Re-imagining Diplomatic Representation as a Pillar of Democracy,” by Nieves Fernanda Cancela Sánchez (Global Advocacy Officer at UNPO, the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization).

Discussants

Christopher N. Magno (Associate Professor in the Department of Justice Studies and Human Services at Gannon University).

(TBC)

Session 14

From Bots to Ballots: AI, Populism, and the Future of Democratic Participation

Date/Time: Thursday, March 19, 2026 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Brian Ball (Associate Professor, Northeastern University London & University of Oxford,Faculty of Philosophy).

Speakers

“Conceptions of Democracy and Artificial Intelligence in Administration and Government: Who Wants an Algorithm to Govern Us?” by Joan Font (Research Professor, Institute of Advanced Social Studies (IESA-CSIC).

“How Does ChatGPT Shape European Cultural Heritage for the Future of Democracy?” by Alonso Escamilla (PhD Student on Cultural Heritage and Digitalisation, The Catholic University of Ávila in Spain) and Paula Gonzalo (Researcher, University of Salamanca, Spain).

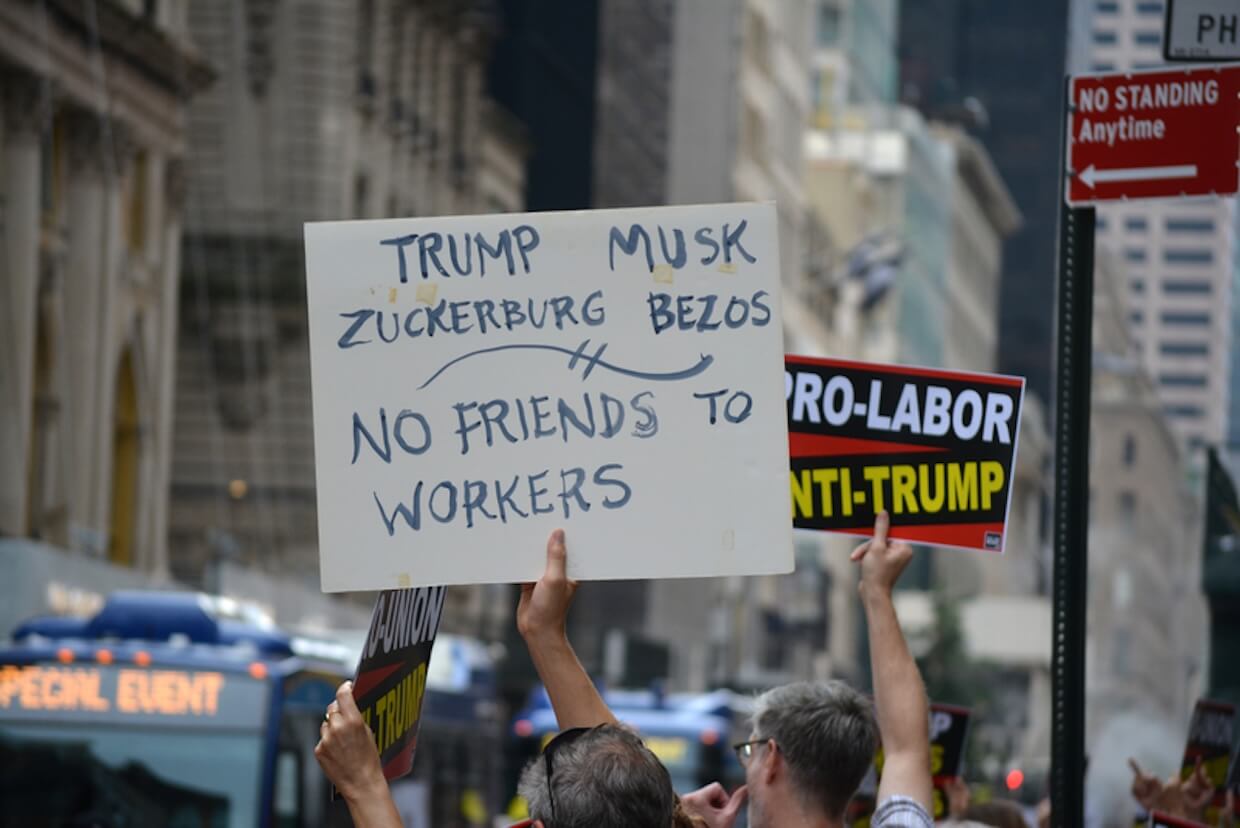

“The New Elite: How Big Tech is Reshaping White Working-Class Consciousness,” by Aly Hill, (PhD candidate, Department of Communication at The University of Utah).

“Bubbles, Clashes and Populism: “The People” in an algorithmically mediated world,” by Amina Vatreš (Teaching Assistant, Department of Communication Studies and Journalism, Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Sarajevo).

Discussants

(TBC)

Session 15

From Populism to Global Power Plays: Leadership, War, and Democracy

Date/Time: Thursday, April 2, 2026 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

(TBC)

Speakers

“Pericles’ Funeral Oration: A Populist Rhetoric for War and Politics,” by Elizabeth Kosmetatou (Professor, History Faculty,University of Illinois, Springfield).

“Can Democracy (or Anything Else) Rescue Civilization While the Rules Keep Changing?” by Robert R. Traill (PhD in Cybernetics/Psychology at Brunel).

“The Politics of Manipulated Resonance: Personalised Leadership in Populism,” by Lorenzo Viviani (Professor, Political Sociology, Department of Political Science, University of Pisa, Italy).

“The Exclusionary Identity of ‘The People’ in Radical Right Populism,” by Cristiano Gianolla (Researcher, Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra; Lisete S. M. Mónico (Associate Professor, Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, the University of Coimbra) and Manuel João Cruz (Post-doctoral researcher, Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra).

Discussants

(TBC)

Session 16

Voices of Democracy: Art, Law, and Leadership in the Era of Polarization

Date/Time: Thursday, April 16, 2026 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

(TBC)

Speakers

“Cultivating Democracy through Art: Laibach’s Contribution in Analyzing Nationalisms and Feelings of Ethnic Belonginess,” by Mitja Stefancic (Independent Researcher, Civil Servant, Italy).

“The Hidden Agenda of Bollywood: The Rise of Hindutva Narratives in Indian Cinema,” by Devapriya Raajev (MA candidate, Sociology, South Asian University, New Delhi).

“’ I Miss My Name’: Why Black American Election Workers Like Ruby Freeman Turn to Defamation Law to Defend Democracy,” by Ciara Torres-Spelliscy (Brennan Center Fellow and Professor of Law at Stetson University).

“State Institutions in Divided Societies: Religious Policy and Societal Dissatisfaction in the Israeli Military,” by Niva Golan-Nadir (Postdoctoral Fellow at Reichman University) and Michael Freedman (Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Political Science and International Relations, Hebrew University of Jerusalem).

Discussants

(TBC)

Biographies & Abstracts

Session 1

The Rise of Populist Authoritarianism around the World

Date/Time: Thursday, September 4, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Oscar Mazzoleni is a professor in political science and political sociology at the University of Lausanne where he leads the Research Observatory for regional research. He is currently the principal investigator the international project “Populism and Conspiracy” funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Austrian Science Fund. He is co-director of the international research laboratory ‘Parties, political representatives, and sustainable development, at the University of Lausanne in collaboration with Laval University.

His works have been published in several peer-reviewed journals as European Politics and Society, Government and Opposition, Political Studies, Party Politics, Swiss Political Science Review, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, Territory, Politics, Governance, Comparative European Politics, Contemporary Italian Politics, Socio-economic Review, Regional and Federal Studies, Journal of Borderlands studies, Revue française de Science politique, and Populism amongst others. He has published 45 books in 4 languages (English, Italian, French and German). His latest volumes include “The People and the Nation. Populism and Ethno-Territorial Politics in Europe (ed. with R. Heinisch and E. Massetti Routledge 2019), “Political Populism. Handbook of Concepts, Questions and Strategies of Research” (ed. with R. Heinisch and C.Holtz-Bacha, Nomos, 2021); “Sovereignism and Populism : Citizens, Voters and Parties in Western European Democracies” (ed. with L. Basile, Routledge 2022); “National Populism and Borders: The Politicisation of Cross-border Mobilisations in Europe” (Elgar 2023); “Populism and Key Concepts in Social and Political Theories” (ed with. C. De la Torre, Brill, 2023), and “Territory and Democratic Politics. A Critical Introduction” (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2024).

He was the principal investigator of many research projects, including four funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. He has pursued an interdisciplinary educational path, earning a degree in sociology and anthropology, as well as a PhD in contemporary history, from the universities of Lausanne and Turin. He was a visiting professor and research fellow at the Universities of Columbia, Laval, Geneva, Groningen, Torino, Sorbonne-Panthéon- Paris, Science-Po-Paris, Valencia, Salzburg, European University Institute of Florence, Cornell University, and La Tuscia. His interests are devoted on political parties, populism, nationalism, regionalism, and Swiss politics in comparative perspective.

Introduction

David J. Sanders is a professor emeritus of political science at the University of Essex. Professor Sanders is an internationally renowned expert on British politics and was appointed the UK’s first Regius Professor of Political Science. Professor Sanders has been a key figure in the achievements of Essex’s Department of Government, which has topped the UK politics rankings for the quality of its research in every national research assessment in the last 25 years.

After studying at Essex as a postgraduate student, Professor Sanders started teaching politics at the University in 1975. He is author of numerous influential books and articles on UK politics, including Lawmaking and Cooperation in International Politics, 1986 and Losing an Empire, Finding a Role, 1990. He co-authored Political Choice in Britain, 2004, Performance Politics and the British Voter, 2009, Affluence, Austerity and Electoral Change in Britain, 2013 and The Political Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Britain, 2013.

He also co-edited the top UK political science journal, the British Journal of Political Science, between 1990 and 2008.

Professor Sanders is a Fellow of the British Academy and received a Special Recognition Award from the Political Studies Association in 2012 for his commitment to outstanding research, which has shaped public understanding of politics. From 2000 to 2012, he was a Principal Investigator for the British Election Study, which is conducted at every General Election to study electoral behaviour and how elections contribute to the operation of our democracy. This prestigious study was based at Essex from 1974 to 1983 and from 2000 to 2012.

Paper 1: The Rise of Populist Authoritarianism in India and the US: Do Family Dynasties and Big Businesses Really Control Democracy?

Abstract: Both India and the US seem to be in the grip of a populist movement that seems to share power with political dynasties and big business. How is this possible in a democracy? We examine this question by comparing families and dynasties in both countries — Kennedy vs Gandhi, currently out of power; Trump vs Modi, now in power. Both nations claim to be vibrant democracies, where populist nationalists have swept into power. Historically, India has been led by charismatic members of one dynastic family, namely the Gandhis; while the US definitely has political families (such as the Adams, Bushs, Rockerfellers, Clintons and now Trumps) it has not been dominated by one or two family dynasties in the way Asian democracies have been after colonialism ended.

Similarly, businesses have played a major role in politics of India and the US, but the business takeover of democratic institutions has had a bigger hand in the US politics than in India until recently; India was a quasi-socialist country till the 1990s. Both polities seem to be moving closer to big business, playing a major role in shaping policy and trade. Thus, we ask the question: are democracies at this populist moment in global politics controlled by the patricians (robber barons, big-tech, oligarchs) – big business and political dynasties? Our methodological approach is psycho-historical and biographical, while staying abreast of demographic data.

We compare the Kennedys vs. the Gandhis; and Trump vs Modi. The Gandhi family has dominated Indian politics for half of its modern history since gaining independence from British rule in 1947; while at least one member of the Kennedy family has been in power for at least the past fifty years in local or federal office, they’ve never held power in the way the Gandhi family did in India. Here we compare women leaders in both family histories, Indira Gandhi vs Kennedy female leaders. In comparing Trump vs. Modi we see a clear difference between two societies; Modi is not a billionaire, unlike Trump, rather a tea-seller from very humble origins. Yet, their populist governments have given power sharing arrangements to the big-business and big-tech oligarchs. When we compare the narrative of these two leaders we see a strong nationalistic streak that mobilizes populism in favor of nativism and an anti-globalist agenda. The key question is are these societies converging or diverging? On the question of authoritarianism and populism they are converging, as India rises as an economic power and the US tries to remain a global democratic power, even though their local cultural politics are remarkably different.

Dinesh Sharma,Ph.D., is a social scientist with a Doctorate from Harvard University in human development and psychology. He is currently Director and Chief Research Officer at SteamWorksStudio in Central-Southern Jersey (an edu-tech venture), consultant at Fordham Institute for Research Service and Teaching (FIRST), and contributing faculty at Walden University. He was associate research professor at the Institute for Global Cultural Studies, Binghamton University, SUNY; a senior fellow at the Institute for International and Cross-Cultural Research in New York City; and a columnist for Asia Times Online, Al Jazeera English and the Global Intelligence among other syndicated publications. His biography, titled “Barack Obama in Hawaii and Indonesia: The Making of a Global President,” was rated a Top 10 Book of Black History for 2012 by the American Library Association. His next book, “The Global Obama” has been widely reviewed and received the Honorable Mention on the Top 10 Black History Books for 2014. His book on Hillary Clinton examined the rise of women politicians before the “Me Too” movement, “The Global Hillary: Women’s Political Leadership in Cultural Context” (Routledge, 2016) and was favorably reviewed.

Shoshana Baraschi-Ehrlich, is a graduate student from New York City, currently studying at Fordham’s Graduate School of Education. Her academic interests focus on the psychological impacts of early-life trauma and the integration of mindfulness techniques in clinical settings to support emotional, cognitive, and physical integration. She is also engaged in research exploring the relationship between trauma and democracy. Shoshana is passionate about bridging psychological theory with real-world practice and plans to pursue a career in clinical psychology.

Paper 2: Out-groups and Elite Cues: How Populists Shape Public Opinion

Abstract: Populist leaders claim they are the true representative of “the people” against corrupt elites and various out-groups (very often immigrants) who are thought to threaten the well-being of the nation. If this is so, the leader is simply reflecting the will of the people as they ascend to power and carry out their agenda. From this view, the populist leader answers the call of the people and uses power to protect and restore the country by targeting the elites and out-groups that threaten it. However, populist leaders do not just reflect the will of the people, they actively cultivate public support for their political agenda. From this view, populist leaders deploy their rhetorical powers to persuade, and even manipulate, the people, by tapping into anxieties that build public support for the populist leader’s agenda. Moreover, the power of populist leaders to focus the attention of voters on the threats to their well-being enables them to tap into in-group fears of various socio-demographically different out-groups. Indeed, truly gifted populist orators can manufacture fear and anxiety by targeting specific out-groups as the “cause” of the economic, social, or political problems that, in their view, threaten the nation.

In this paper, we examine results from a nationally representative survey conducted in the U.S. in October of 2024 to measure the ability of U.S. President Donald Trump to influence public opinion. We examine his ability to increase or decrease public support for a range of policies, specifically refugees and trade. Our survey allows us to compare how respondents view refugees depending on whether those refugees are from Ukraine or from Gaza, and how respondents view trade from Europe or from China. Moreover, our survey allows us to assess whether public opinion is more readily shaped by the cues provided by political leaders (what we call “follow-the-leader” effects) or by the social attributes of the “out-group” (what we call “social attributes” effects), both of which are important components of populist rhetorical appeals.

Michael Makara is an Associate Professor of Comparative Politics and International Relations. He received his Ph.D. and M.A. in Political Science from the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University, and his B.A. from Virginia Tech. Professor Makara’s research focuses on politics in authoritarian regimes and civil-military relations, with a regional focus on the Middle East. His research appears in Democracy and Security, Defense and Security Analysis, and the Journal of the Middle East and Africa. At UCM he teaches a variety of courses related to comparative politics and politics of the Middle East. Every year, he leads a study abroad program to Jordan and Israel that aims to challenge students’ perceptions of the region. He recently published an article in the Journal of Political Science Education (with Kinsey Canon) that explores the impact of this program on the extent to which students adhere to common stereotypes of the Middle East. Dr. Makara also sits on the Board of Directors for the International Relations Council (IRC) of Kansas City and is the director the Mideast meets Midwest project to expand opportunities for university students to pursue Middle Eastern Studies.University of Central Missouri & Dr. Gregory W. Streich, University of Central Missouri.

Gregory W. Streich is Professor of Political Science and Chair of the School of Social Sciences and Languages. He has published on a range of topics, including democratic theory, social capital, justice, and American Exceptionalism. Most notably, he has authored or co-edited three books: Justice Beyond “Just Us”: Dilemmas of Time, Place, and Difference in American Politics, U.S. Foreign Policy: A Documentary and Reference Guide, and Urban Social Capital: Civil Society and City Life. Additionally, he has won several awards for his teaching and research, including the Distinguished Faculty Award from the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Paper 3: From Economic to Political Catastrophe: Four Case Studies in Populism

Abstract: This paper is meant to be a comparative study between four international crises: the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, Argentina’s 2001, the US’s Great Recession of 2008, and Greece’s Great Depression of 2010. It has been argued by economists, historians, and political scientists that economic crises produce populist movements in the countries that experience them (Kindleberger, 2005; Ferguson, 2012; Hartleb, 2012). Kindleberger argues that all economic crises are a product of a “bubble” or a “mania” and as such the corrective response is an economic crisis in the country that experiences such market inflation. As an economist, however, he says nothing of the impact of the crisis on the politics of the country or the responses to said crisis.

Generally speaking, populism has been at the forefront of countries with great inequalities in places like Latin America or India or in countries under severe socio-economic stress such as Weimar Germany. Yet the European Union may be in a recession but it could hardly be justification for the multitude of populist (anti-EU, anti-globalization, xenophobic, and racist) movements that have sprung up even in countries with solid economies such as Finland, Denmark, and UK. It is thus important to analyze the types of responses to these crises and the types of populism, if any, each country experiences as a result of a given crisis, accounting for its severity and the administrative and decision-making capacity of the state apparatus.

The association of economic crisis and populism seems to hold true in modern times in many areas of the world. In Thailand after the catastrophic collapse of the Thai Baht in 1997, in Argentina in 2001, and in the US after 2010, one can debate whether the bursting of the dot com bubble constitutes a crisis, but mostly after the collapse of the real estate market bubble of 2008 and more recently in Greece in 2010. Yet, in all those countries the experience with populism is different and the pressure created by the economic condition on the ground leads to different outcomes in the politics of those countries. In Thailand, the reaction to post-crisis populism was a coup, in Argentina was an extended period of “Kirchnerismo” , in the US the rise of what Hofstadter the “Paranoid Style in American Politics”, as well as the more traditional non-party political movements hat put enormous pressure on the traditional party structure pushing liberal democracy to the brink, while in Greece populism which is more associated with European populist tradition as experienced in most pre-and post-WWII countries created a hybrid nationalist-leftist populism more akin to early twentieth century European Corporatism. This research intends to highlight the political processes, Institutions, and leaders who have influenced the course of politics and argue that in all four cases, the best predictor for post-crisis behavior is the national political culture.

Akis Kalaitzidis is a professor of political science at the Department of Government, Law, and International Studies, University of Central Missouri. He received his B.A. from the University of Tennessee-Knoxville in Economics and Political Science, and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Temple University in Philadelphia in Political Science. He joined the UCM faculty in 2004. He teaches a variety of classes, including American Government, The European Union, World Politics, International Organizations, and American Foreign Policy. He was Rotary Peace Fellow at the Rotary Peace Center Chulalongkorn University’s Program in Conflict Resolution and has been the director of the Missouri Ghana program (2011) and Missouri Greece program (2015). He is the author of Europe‘s Greece: A Giant in the Making, published by Palgrave McMillan (2010) and co-edited with Dr. Streich US Foreign Policy: A Documentary and Reference Guide (Greenwood 2012) among others. His work appears in a variety of journals, book reviews/contributions, and conference publications.

Paper 4: Populism, Clientelism, and the Greek State under Papandreou

Abstract: This paper explores the role of populism and clientelism in shaping the Greek state under the leadership of Andreas Papandreou, one of Greece’s most influential political figures. Papandreou served as Prime Minister from 1981 to 1989 and again from 1993 to 1996. His tenure coincided with a period of profound political and economic transformation following the restoration of democracy in 1975. His governance combined populist rhetoric with clientelist practices, crafting a distinctive political strategy that left a lasting impact on Greek politics. At the core of Papandreou’s political success was his ability to mobilize popular support through populist appeals, emphasizing social justice, nationalism, anti-Americanism, and the welfare state. He positioned himself as a champion of the common people, presenting the Socialist Party as the defender of workers’ rights and national sovereignty, even as he reversed course on many of his programmatic policies.

Papandreou’s populism resonated deeply with the large segment of the Greek population that right-wing establishments had marginalized following the Greek Civil War (1946-1949) and the collapse of the military junta (1967-1974). As these disenfranchised groups leaned politically to the left, Papandreou shifted his stance from the center to the left, incorporating a more left-wing faction within his party. His message of social and economic justice empowered these communities, offering them a sense of inclusion and challenging the longstanding dominance of conservative elites. In parallel with his populist narrative, Papandreou employed clientelism as a tool for political stability. The distribution of state resources and public sector jobs—particularly after Greece acceded to the EEC and the influx of investment funds—was often based on loyalty rather than merit. This system of patronage not only secured votes but also fostered a political culture of dependence on the state for material rewards.

This study explores the interaction between populism and clientelism in shaping the Greek state. It investigates Papandreou’s policies’ influence on Greece’s political culture, governance frameworks, and public administration and their enduring effects on the nation’s journey within the European Union. The analysis ultimately provides a critical evaluation of how populist rhetoric and clientelist strategies reinforced democratic institutions in Greece and altered state-society dynamics during the late 20th century.

Elizabet Kosmetatou is a Professor of History at the University of Illinois Springfield.

Session 2

The ‘Nation’ or just an ‘Accidental Society’: Identity, Polarization, Rule of Law and Human Rights in 1989-2025 Poland

Date/Time: Thursday, September 18, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Abstract: In principle, the Polish transition to democracy initiated in 1981 was understood as liberation from Soviet colonialism, Communist totalitarian state ideology at the national level and “the resurrection of rights” (Kurczewski, 1993) at the individual level.

In practice, it quickly became controversial how the “will” of the nation should be determined and whose rights should be resurrected. The problem was nicely captured by a Christian member of the Polish Parliament, voicing objection to the abortion referendum on the grounds that such fundamental and morally-loaded issues could not be decided by “the accidental society” (in other words, the voting public).

Two decades later, opening debate that will be called “the four hours of anti-philosophy of law” (Safjan, 2015) the honorary speaker of Polish Parliament proclaimed that “law shall serve us. Law that does not serve the nation is lawlessness”. “Poland’s constitutional breakdown” (Sadurski, 2019) dutifully followed, beginning with “war” with the Constitutional Tribunal and ordinary courts.

Panellists will discuss:

-the concept of nation – civil and national} underpinning “Solidarity’s” resistance to the communist rule, and its evolutions after the 1989 breakthrough (Joanna Kurczewska),

-the shifting patterns of the political polarization and its impact on key liberal-democratic institutions like Parliamentary law-making process, Presidency and the Constitutional Court (Kamil Jonski),

-the sociological dimensions of the “rule of law” including the democratic transition, post-2015 backsliding and post-2023 restoration in context of doctrine of separation of powers (Jacek Kurczewski),

-the implications for the protection of human rights, with particular emphasize on woman’s rights (including access to the abortion) and minorities rights (Malgorzata Fuszara).

Varieties of Polish Patriotism: Experience of “Solidarity” 1980-1989 in Context of History and Anthropology of Ideas

Joanna Kurczewska is a full professor in the humanities and head of the Sociology and Anthropology of Culture Team at the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Graduated University of Warsaw, Ph.D. at the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences (The Problem of the Nation in Polish Sociology at the Turn of the 19th and 20th Centuries. A Comparative Analysis of Selected Concepts), habilitated doctor (Technocrats and the Social World – Analysis of Technocratic Ideas).

In 1981, co-operated with the Centre for Social and Professional Work at the National Commission of NSZZ “Solidarity” Trade Union as co-chair of the Union History Group.

A corresponding member of the Second Faculty of History and Philosophy of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences (since 2011) and vice-president, formerly president of the Commission on Civilization Threats of the above Academy, a member of the Warsaw Scientific Society (since 2009), In 2007, she was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta. Selected publications: National Identities vis-a-vis Democracy and Catholicism – The Polish Case after 1989 (2005), Researcher vis-a-vis the Local Community (2008), Squeezing Brussels Sprouts? On the Europeanization of Local Communities in the Borderlands (2009).

Single Text, Clashing Meanings: Political Polarization, Constitutional Axiology and the Polish Constitutional Quagmire

Kamil Joński is an economist who graduated from SGH Warsaw School of Economics with a Ph.D. in law at the University of Lodz (Constitutional Tribunal and the Political Conflict – Law & Economics Perspective). He is an assistant at the Collegium of Socio-Economics, SGH Warsaw School of Economics. He works at several research projects financed by Polish National Science Centre, at Cracow University of Economics, SGH Warsaw School of Economics and Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan. Jónski worked on Regulatory Impact Assessments (RIA) in Polish Ministry of Justice (2012-2016) and on economic analysis of judicial system in MoJ’s supervised Institute of Justice (2016-2017). Since 2017, he is employed at Polish Supreme Administrative Court.

Selected papers: Return to Power: The Illiberal Playbook from Hungary, Poland and the United States (2024), Legislative inflation in Poland: bird’s eye view on three decades after the the1989 breakthrough (2024), Evidence-Based policymaking during the COVID-19 Crisis: Regulatory Impact Assessments and the Polish COVID-19 Restrictions (2023), Assessments of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal performance: effects of the survey administration method (2023). Co-author of the 2022 report summarizing European Network of Councils for the Judiciary (ENCJ) survey of European judges about their independence.

Protection of Human Rights and Its Implications for Women’s and Minority Rights

Małgorzata Fuszara is full professor of humanities in the field of sociology, Institute of Applied Social Sciences (IASS) University of Warsaw, habilitated doctor in the Sociology of Law, Ph.D. in law. Served two terms as Director of the IASS, joint founder of Poland’s first Gender Studies Program at IASS, head of its Sociology and Anthropology of Custom and Law Chair. In 2014-2015 Plenipotentiary of Polish Government for Equal Treatment. President of Council of Women’s Congress Association, Chairwoman of the Women’s Council under the Mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta. Authored, co-authored and edited numerous publications in Polish, English, French and German, among others: Polish Disputes and Courts (2004), Women in politics (2007), New men? Changing models of masculinity in contemporary Poland (2008), Cooperation or conflict? The State, the Union and Women (2008), Women, elections, politics (2013), Disputes and their resolution (2017), Mass Aid in Mass Escape. Polish Society and War Migration from Ukraine (2022).

Who Speaks for Whom: The Issue of Representation in the Struggle for the Rule of Law

Jacek Kurczewski is full professor of humanities in the field of sociology, Lecturer at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology of Customs and Law at the University of Warsaw. Editor-in-chief of Societas/Communitas. Specializing in the sociology and anthropology of law and customs, continuator of the Leon Petrażycki’s Polish school of sociology, a student of Adam Podgórecki. Former Academic Director of the Oñati International Institute for the Sociology of Law. Member of Warsaw Academic Society.

In 1980–1992 an advisor on Rule of Law to the “Solidarity” Trade Union, member of Lech Wałęsa’s Citizens Committee, participant of the Round Table negotiations of 1989 (sub-table for freedom of association). Judge of the Tribunal of the State (1989-1991). Member of Parliament and Deputy Speaker of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland of the first term (1991–1993). Coauthor of the draft laws: limiting censorship (1981), the law on counteracting drug addiction (1987), the law on assemblies (1990) and the Civil Service Code (2003). In 2007 awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta. Member of the Program Councils of the Polish public TV broadcaster and pollster CBOS Foundation. Author of The Resurrection of Rights in Poland (1993) and numerous research papers.

Chair

Mavis Maclean is a Senior Research Fellow of St Hilda’s College and a Research Associate at Department of Social Policy and Intervention. She has carried out Socio Legal research in Oxford since 1974, and was a founding director of OXFLAP in 2001. She has acted as the Academic Adviser to the Lord Chancellor’s Department, and served as a panel member on the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry between 1998 and 2001, a major public inquiry into the National Health Service. Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire

Discussants

Dr. Magdalena Solska is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Fribourg. She currently directs the research project “Political opposition in post-communist democracies and authoritarianisms,” funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PRIMA Grant) in the period of 2023-2027. Her research focuses on political systems after communism and specifically on forms, strategies and institutionalization of opposition in selected countries in Central and Eastern Europe.

Professor Barry Sullivan is the Raymond and Mary Simon Chair in Constitutional Law and the George Anastaplo Professor of Constitutional Law and History. Before joining the Loyola faculty, Professor Sullivan had a varied career in the private practice of law, government legal practice, the teaching of law and public policy, and university administration. Professor Sullivan was Dean of the School of Law at Washington and Lee University from 1994 to 1999 and Vice-President of the University in 1998-99. He was also a long-time litigation partner at Jenner & Block (1981-94, 2001-09), where he focused on appellate practice.

Professor Krzysztof Motyka is a legal philosopher and sociologist of law, Chair of Human Rights and Social Work (earlier: Sociology of Law and Morality) at John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin. Fulbright senior scholar in the Center for the Study of Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley (1994/1995), visiting researcher at the George Washington University, Washington, D.C. (July-October 2015). Member of the Minister of Foreign Affairs’ Advisory Board on Human Rights (2001 -2002) and of the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (2007-2012). Editor of “KUL Research Bulletin,” organizer of annual “Human Rights Days Conference.”

Session 3

Populism, Freedom of Religion and Illiberal Regimes

Date/Time: Thursday, October 2, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Marietta D.C. van der Tol is Landecker Lecturer at the Faculty of Divinity, Affiliated Lecturer in Politics and International Studies, and Senior Postdoctoral Researcher at Trinity College, Cambridge.

She studied law and history at Utrecht University (LLM, MA) and the history of Christianity at Yale (MAR) before completing her PhD at Cambridge (2020) on Politics of Religious Diversity, examining tolerance and visibility of religion in constitutional law and politics in France, Germany, and the Netherlands.

She has held research and teaching positions at Oxford (Blavatnik School of Government, St Peter’s, Lincoln College) and Cambridge (Leverhulme Early Career Fellow, 2024–25).

Her current projects include leading interdisciplinary networks on religion, nationalism, and democracy, and co-directing research on Protestant political thought. She has co-edited special issues in Religion, State & Society and The Journal of the Bible and its Reception and convenes the annual Political Theologies conference series.

Discussants

Simon P. Watmough (PhD) is a freelance academic researcher and editor and serves as a non-resident research fellow in the research program on authoritarianism at ECPS. He was awarded his Ph.D. from the European University Institute in April 2017 with a dissertation titled “Democracy in the Shadow of the Deep State: Guardian Hybrid Regimes in Turkey and Thailand.” Dr. Watmough’s research interests sit at the intersection of global and comparative politics and include varieties of post-authoritarian states, the political sociology of the state, the role of the military in regime change, and the foreign policy of post-authoritarian states in the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Erkan Toguslu (PhD) is a researcher at the Institute for Media Studies at KU Leuven, Belgium. He received his M.A. and Ph.D. in sociology from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris. His research focuses on transnational Muslim networks in Europe, the emergence of Islamic intellectuals, interfaith dialogue, the debate on public-private Islam, and the nexus of religion and radicalization.

ErkanToguslu is co-editor of Journal of Populism Studies (JPS) and the editor of Everyday Life Practices of Muslims in Europe (Leuven University Press); Europe’s New Multicultural Identities (Leuven University Press and co-edited with J. Leman and I. M. Sezgin); and Modern Islamic Thinking and Islamic Activism (Leuven University Press and co-edited with J. Leman). His recent publications on violent extremism and Muslim extremism include: “Caliphate, hijrah, and martyrdom as a performative narrative in ISIS’ Dabiq magazine,” Politics, Religion and Ideology, 20 (1), 94-120; and “Capitalizing on the Koran to fuel online violent radicalization: A taxonomy of Koranic references in ISIS’s Dabiq,” Telematics and Informatics, 35 (2), 491-503 (co-authored).

Paper 1: Religious Freedom as Hungaricum Hungarian Illiberalism and the Political Instrumentalization of Religious Freedom

Abstract: In 2025, the Hungarian government announced it was creating a “Religious Freedom” caucus in the European Parliament. Domestically, Hungary has claimed a special relationship to the value of religious freedom since at least 2020, when the Hungarian parliament voted to enshrine religious freedom as an intangible value of Hungarian heritage (Hungarikum). On the one hand, the rising prominence of this discourse of religious freedom was precipitated by immediate political concerns as the Hungarian government has tried to distract attention from negative judgements at the European Court of Human Rights. On the other, this paper will go beyond journalistic accounts of political strategizing in order to sketch an outline of the emerging illberal political institutionalization of religious freedom. I will focus on the network of Hungarian institutional political actors that enact this discourse at the European and domestic levels, and detail the forms of publicly acceptable religious practice enabled by these institutions.

Marc Loustau is a cultural anthropologist and journalist reporting on religion and nationalism in Eastern Europe. Based in Budapest, Hungary, he is fluent in English and Hungarian and proficient in Romanian. His reported features and commentary have appeared in major U.S. and European newspapers and magazines. Drawing on his academic research, he provides smart and surprising fact-based commentary on contemporary events. He has delivered invited lectures at universities across Europe and North America and has presented at numerous international conferences. His book Hungarian Catholic Intellectuals in Romania: Reforming Apostles examines how contemporary Hungarian Catholic intellectuals are forging an ethical concept of nationhood.

Paper 2: Religious or Secular Freedom? On Pragmatic Politicization of Religion in Post-socialist Slovakia

Abstract: Since 1989, elements of radical Christian activism in Slovakia that have been frequently characterized as representing the ‘culture of life’ have been challenging the regime of post-socialist liberal constitutionalism represented by the European status quo. This challenge has primarily consisted of accusations that the latter suppresses newly acquired religious freedoms. The most significant counterpart of this radicalism – secular progressivism – has been arguing against expanding ecclesiastical privileges in the sphere of financing, education, and culture. Traditional social-confessional divisions in Slovak society have weakened, reshaping the discussion away from political freedom for all and toward a debate about who is suffering more oppression. In this conflict, the most profitable have been political entrepreneurs, especially current Prime Minister Robert Fico, who utilizes “culture war” discourse in his populist mobilizations.

Juraj Buzalka is Associate Professor of Social Anthropology at Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia, where he has taught since 2006. His research focuses on the anthropology of political movements, exploring intersections of nationalism, populism, religion, and politics, particularly in Eastern and Central Europe. He is also interested in the politics of memory and the cultural dimensions of wine and food movements. Since 2013, he has been based at the Institute of Social Anthropology within the Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences.

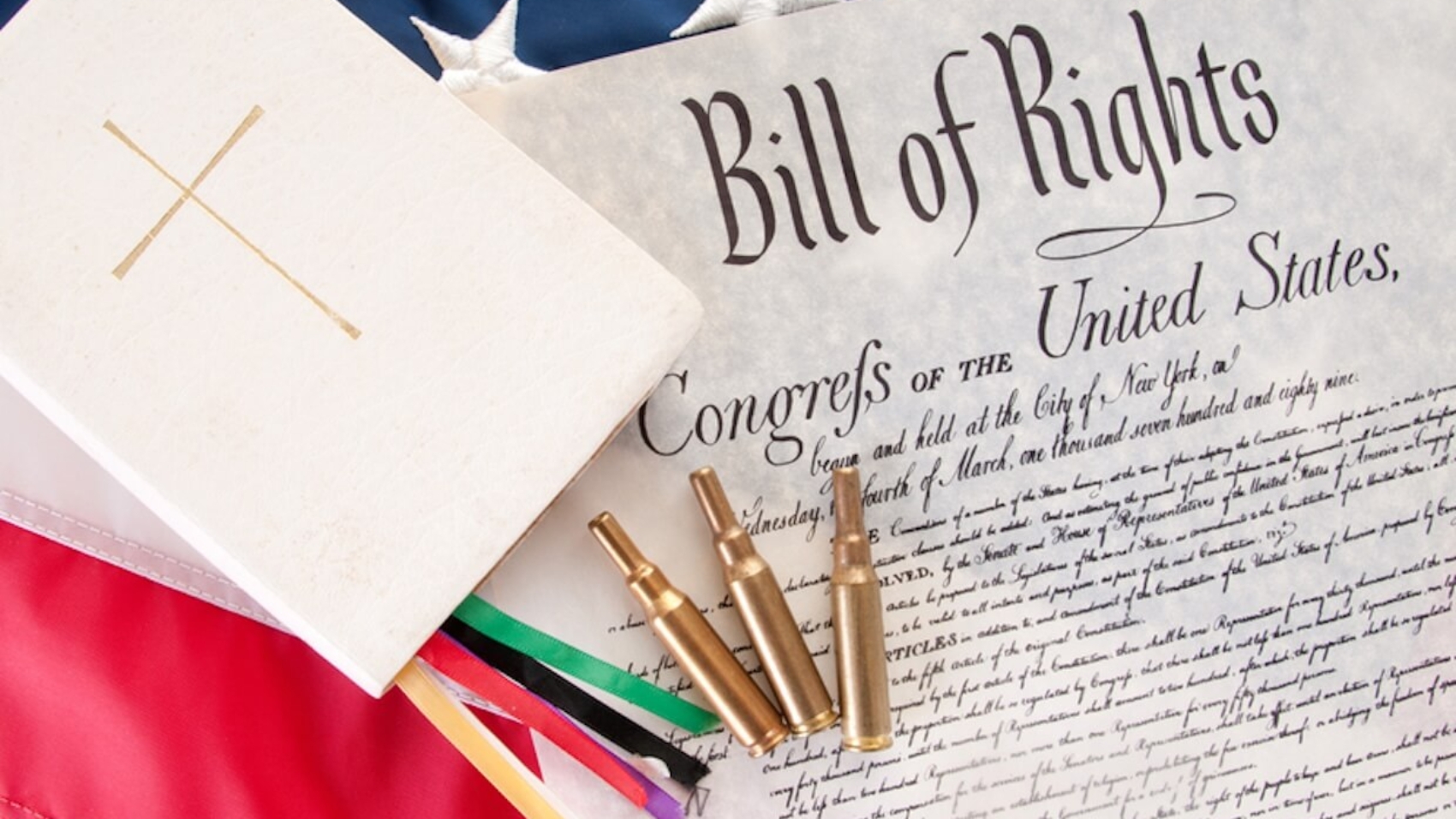

Paper 3: Illiberal Theocracy in Texas? The Incorporation of Evangelical Christian Theology into State Law

Abstract: This year, Texas marks three consecutive decades of governance by the Republican Party. In that time, the party has built up what can be described as a theocratic illiberal regime. The theological positions of many of the state’s evangelical Christians have been incorporated into state law, often under the guise of religious freedom. In his paper, our third panelist, the Rev. Dr. Colin Bossen, himself a Texas-based clergyman, will reflect how the rhetoric of religious freedom has been used to further the construction of an illiberal state within the United States federal system, eroded supposed the separation of church and state, and undermined freedom of religion itself.

Rev. Dr. Colin Bossen, First Unitarian Universalist of Houston and Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford. He earned a Ph.D. in American Studies and an A.M. in History from Harvard University. A graduate of Meadville-Lombard Theological School, he was ordained by the Unitarian Universalist Church of Long Beach in 2007. Since 2018, he has served the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Houston. Before moving to Texas, he served congregations in California, Massachusetts, and Ohio. He has held non-residential fellowships at Rice University and Princeton University. A scholar and social justice activist he has helped organize multiple labor unions—including acting as one of the founders of the Harvard Graduate Student Union. He currently has three books under contract. The first is on contemporary Unitarian Universalist theology (Brill). The second collects his 2019 Minns lectures on American Populism and Unitarian Universalism (Palgrave Macmillan). And the third is focused on the political theologies of populism (Wayne State University Press).

Session 4

Performing the People: Populism, Nativism, and the Politics of Belonging

Date/Time: Thursday, October 16, 2025 – 15:00-17:30 (CET)

Chair

Oscar Mazzoleni is a professor of political science and political sociology at the University of Lausanne, where he leads the Research Observatory for Regional Research. He is currently the principal investigator of the international project “Populism and Conspiracy” funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Austrian Science Fund. He is co-director of the international research laboratory ‘Parties, political representatives, and sustainable development, at the University of Lausanne in collaboration with Laval University.

Discussants

Abdelaaziz El Bakkali is an associate professor of Media and Cultural Anthropology at SMBA University in Fes, Morocco, and a Post-Doc Fulbright visiting scholar at Arizona State University in the US (2024/25), a PhD Joint-Sup at SIU, Illinois (2009/10), and a US Dept of State Fulbright Visiting P4T at UD Delaware (2007/2008). He obtained his PhD (2014) in media and communication from MVU, Rabat. His works focus on cultural studies and anthropology, primarily in the areas of media, gender, and religious studies. He has edited some books in these related research areas. Aziz has also written many articles in these related fields. El Bakkali has conducted other educational research, having taught English for over 24 years. He has published numerous articles in this field, which are featured on Publons, Google Scholar, SSRN, and other highly indexed works.

Azize Sargin is an independent researcher and consultant on external relations for non-governmental organisations. She holds a doctorate in International Relations, with a focus on Migration Studies, from the Brussels School of International Studies at the University of Kent. Her research interest covers migrant belonging and integration, diversity and cities, and transnationalism. Azize had a 15-year professional career as a diplomat in the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where she held various positions and was posted to different countries, including Romania, the United States, and Belgium. During her last posting, she served as the political counsellor at the Permanent Delegation of Turkey to the EU.

Paper 1: We, the People: Rethinking Governance Through Bottom-Up Approaches

Abstract: Democracy is often celebrated as a governance system that ensures citizen participation and accountability. However, in practice, centralized power structures often alienate the people and limit genuine participation, leading to political exclusion, inefficiency, and social unrest. This paper advocates for bottom-up approaches to governance as essential for realizing inclusive democracy and sustainable development. Using Nigeria as a case study, it highlights the limitations of top-down governance, as seen in widespread corruption, economic disparities, and rising public discontent. The study explores key strategies for enhancing participatory governance, including decentralization, civic education, community-based development, digital democracy, and legislative reforms. By shifting decision-making closer to the grassroots, these approaches empower citizens, enhance transparency, and promote equitable resource distribution. Empirical evidence from global case studies, such as participatory budgeting in Brazil and decentralized governance in Uganda, supports the argument that bottom-up models lead to improved governance outcomes. It further demonstrates the interdependence of participatory governance and sustainable development, as nations that prioritize inclusivity experience greater political stability, economic growth, and social cohesion. The persistent challenges in Nigeria – ranging from separatist movements to youth-led protests like #EndSARS – underscore the urgent need for governance reforms that integrate local voices into policymaking. Ultimately, this paper advocates for a fundamental shift in governance – one that places the power of decision-making in the hands of the people. By adopting citizen-driven governance, nations can close the gap between leaders and the governed, ensuring greater accountability, inclusivity, and democratic integrity.

Samuel Ngozi Agu is a distinguished academic and the Dean of the MJC Echeruo Faculty of Humanities at Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria. With a Doctor of Philosophy in Social and Political Philosophy from the University of Port Harcourt, he is also an Inaugural Lecture Laureate, recognized for his impactful scholarship. He holds a postgraduate certificate in Mediation and Democratic Dialogue from the Central European University, Budapest, and a Professional Certificate in Mediation and Democratic Dialogue from the Benjamin Cardozo and Hamline Universities’ Schools of Law, in collaboration with the American Bar Association. With over 16 peer-reviewed journal articles, 15 contributions to university research books, seven authored books, and two co-authored books, Professor Agu’s work spans critical areas in social and political philosophy, with a focus on democracy, good governance, logic, critical thinking and youth entrepreneurship. He has presented his research at numerous national and international conferences, reflecting his commitment to advancing thought leadership in his fields. Professor Agu had served as Director of the Business Resource Centre (Entrepreneurship) and Director of the University Examination Centre at Abia State University. His leadership and academic endeavors continue to shape both the intellectual and administrative landscape of the institution.

Paper 2: Uses and Meanings of ‘The People’ in Service of Populism in Brazil

Abstract: The implementation of populism is not homogenous among South American countries so populism in this particular region has many variations. Yet, they are similarly determined by episodes of political and social transition – for instance, the crisis of traditional political elites and the appearance of new political actors – along with variables of economic force or instability. Brazil serves as a good example. From the classical populism of Getúlio Vargas in the decade of 1930s until the far-right authoritarian populism of Jair Bolsonaro, all populist experiences in Brazil are linked to important changes in society.

Brazil has experienced several particular populist leaders: some with marked populist features than others; some exposing a reactionary antagonism while others a mitigated one. This empirical variation produced different uses and meanings of “the people” in service of populism in order to try to secure political support and gain elections. But is this variation observed in the rhetoric of the same populist leader over time? Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a democratic and liberal populist leader, is in his third presidential term (2003-2006; 2007-2010; 2023-). He faced three presidential campaigns forged by the particular contexts and crises of each period. The goal of the paper is to identify and explain the uses and meanings of “the people” by Lula in his three political moments. Do they vary according to social demands and the political context of each period, or does the content of the idea of “the people” remain unchanged because it is used by the same populist leader?

As to the methods, the qualitative approach is adopted based on bibliographic and documentary research, including online news materials, official campaign speeches and political programmes. This empirical research aims to contribute to the debate on the concept of ‘people’ as a discursive construction, drawing on the work of Ernesto Laclau. Moreover, the paper argues that the Lula case offers complexity that challenges the view within populism studies that populism is committed to opposing liberal democracies.

Eleonora Mesquita Ceia is a Doctor of Law at the Faculty of Law and Economics, Saarland University, Saarbrücken, Germany. Professor of State Theory at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brazil. Professor in the Postgraduate Program in Contemporary Legal Theories at UFRJ. Currently her research focuses on transitional justice, constitutionalism, democracy, and populism. Her most recently published article was ‘Populism and Constitutionalism in Brazil: An Enduring or Transitional Relationship in Time?’ in Populism and Time: temporalities of a Disruptive Politics edited by Andy Knott.

Paper 3: The idea of ‘People’ within the domain of Authoritarian Populism in India

Abstract: Democracy is considered to be as motherhood and apple pie of any political system (Adam Swift,2014). Till a few years ago, this assumption was challenged mainly by Islamic countries, who were predominantly of the opinion that the West was imposing a liberal democratic set-up on their countries through coercion. Interestingly, during the second decade of the 21st century, the critique of democracy emerged not externally but from the internal system of the democratic political framework.

The socio-political context of this internal critique is Populism of specific variety. It was the origin of a process of disaffection and disgust with liberal institutions, manifested in the increasing level of abstention and apathy (Chantal Mouffe, 2018). From the triumph of liberal democracy to its failure and its insufficient response toward the aspirations of the public, it created an apolitical social sphere. This vacuum was filled up by populist forces in India in 2014.

This upsurge of Hindu Nationalism is a variant of populism based on the emotional appeal to the psychological dimension of Indian society. Along with the failure of the liberal elites, the subalternisation of the political culture has created fertile ground for this variant of populism to develop (Ashutosh Varshney, 2022). Just like all other variants, Hindu Nationalism is essentially anti-institutionalist and restructuring the logic of liberal institutions is one of its objectives (Ajay Gudavarthy,2019). One of the specificities of this populism in India is its organic emergence from the Unconscious domain of Indian society (Ashis Nandy, 2020). Gradually, it acquires authoritarian tendencies of unique character, which we haven’t witnessed till now.

It is in this context this paper will try to delve on the four sets of questions. Firstly, How the political mobilisation of Hindutva is based on politics of emotion? Secondly, in what ways Populist politics within the framework of Hindu Nationalism is unique (authoritarian) in its form and content? Thirdly, can we think of any ‘alternative’ of Populism within the context of India in particular and the world in general? Lastly, theoretically, what would be the sphere of the revolutionary subject (the idea of people) within the space of re-imagined progressive politics (alternative) that this paper intends to think through?

Shiveshwar Kundu is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Kalyani, West Bengal. His academic interests encompass political philosophy, Indian politics, and psychoanalysis. Kundu has contributed opinion pieces and scholarly articles to publications such as Forward Press, Newslaundry, and The Telegraph India, where he addresses issues related to democracy, caste, and ideological movements in India.

Paper 4: We, the People: The Populist Subversion of a Universal Ideal

Abstract: This paper examines the populist redefinition of We, the People and its implications for liberal democracy. Historically an inclusive foundation for democratic citizenship, the phrase has been appropriated by populist movements to delineate a “true people” in opposition to perceived outsiders. Rather than viewing this shift as mere rhetorical manipulation, the paper argues that it reflects a deeper crisis within the liberal-democratic tradition itself. The erosion of a shared conception of citizenship and the common good—exacerbated by identity-driven politics and post-liberal critiques—has facilitated this populist reinterpretation. While populist leaders exploit these fractures, their rise is symptomatic of broader ideological shifts in liberalism, which increasingly prioritizes particular identities over universal democratic ideals. Engaging with contemporary political theory and populism studies, this paper advocates for reclaiming We, the People as a genuinely inclusive democratic principle, emphasizing equality, pluralism, and civic participation as essential to the resilience of liberal democracy.

Mouli Bentman is a researcher and lecturer at Sapir Academic College, specializing in political philosophy and democracy studies. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a DEA from the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) in Paris. His research explores the philosophical foundations of democracy, the relationship between political authority and legitimacy, and the intersection of classical and contemporary political thought. Dr. Bentman’s academic work engages with fundamental questions in political philosophy, including the nature of sovereignty, the evolution of democratic governance, and the role of political myths in shaping collective identities. His scholarship examines both historical and contemporary theories of democracy, with a particular focus on Political Imagination. At Sapir Academic College, he teaches courses on political theory, democratic institutions, and the philosophical underpinnings of modern politics, emphasizing critical engagement with canonical and contemporary texts.

Michael Dahan received his PhD in political science from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2001. Currently his research focuses on two primary areas – the impact of technology on democracy as well as big data, algorithmic regimes and political participation. He provides grounded analysis on a regular basis in both areas and advises on policy issues in his areas of expertise. He is a regular contributor to the media on issues related to technology and politics. Dr. Dahan has extensive first-hand experience in the security and development fields in both policy and practice. At present he lectures on the political and social aspects of hacking and cyber warfare, politics and technology and political populism. He is a senior lecturer in the departments of Public Policy and Public Administration, and Communication Studies, Sapir College, Israel. He has also taught at the Hebrew University, Ben Gurion University, Bar Ilan University, and the University of Cincinnati.

Session 5

Constructing the People: Populist Narratives, National Identity, and Democratic Tensions

Date/Time: Thursday, October 30, 2025 – 15:00-17:00 (CET)

Chair

Dr. Heidi Hart is an arts researcher and practitioner based in Utah, US and Scandinavia. She holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College and a Ph.D. in German Studies from Duke University. She is a Pushcart Prize-winning poet who has also received an ACLS-Mellon Fellowship and local funding for a 2019 conference on the Anthropocene. She completed a postdoc at Utah State University and is a regular guest instructor at Linnaeus University in Sweden.

Dr. Hart has a dual research focus, on political music during and after the Nazi period, and on sound in environmental media today. Her publications include two recent monographs, Hanns Eisler’s Art Songs and Music and the Environment in Dystopian Narrative. She also does curatorial work and coordinates the Ecopoetic Salon, an international platform for artists and researchers in the environmental humanities. She is currently working with the 68 Art Institute in Copenhagen to develop a project on climate grief and new imaginaries for the future.

Discussants

Hannah Geddes is a PhD candidate at the University of St Andrews; her research explores how UK policies surrounding support for asylum seekers are understood, reshaped, and delivered at the local level, against the background of outsourcing and high levels of politicisation. She previously completed an MSc in Refugee and Forced Migration Studies at the University of Oxford and a BSc in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. Hannah has experience working in public sector auditing, and in NGO community organisations which support displaced people in Greece and the UK.

Dr. Amedeo Varriale earned his Ph.D. from the University of East London in March 2024. His research interests focus on contemporary populism and nationalism. During his academic career, Dr. Varriale contributed as a research assistant to the development of a significant textbook project on the global resurgence of nationalism, titled“The New Nationalism in America and Beyond,” co-authored by Robert Schertzer and Eric Taylor Woods. He has written for ECPS before but has also been published by other academic outlets ranging from the Journal of Dialogue Studies to UEL’s Crossing Conceptual Boundaries. Currently, he is also an “affiliated researcher” for the Centre for the Study of Global Nationalisms (CSGN).

Paper 1: The Romanian and Hungarian People in Populist Leaders Narratives between 2010-2020

Abstract: The paper will analyze the construction of the Romanian and Hungarian people in the speeches of the political leaders of the ruling parties in the two countries between 2010-2020. Considering the centrality of the concept of the people for populist theory, the main question of the paper is how it was constructed and what resources were used in this construction. The hypothesis suggested is that the political leaders used narratives about the past which reflect a historical clash between two visions about how the Romanian and Hungarian people to be built. In order to test the hypothesis will be used the qualitative analysis in a deductive approach. The analysis will try to unravel the narratives and expose the characteristics attributed to the Romanian and Hungarian people. The speeches will be selected considering the significance of the moment when were delivered, like national commemorative or celebration days as well as during electoral campaigns or related to important events.

Gheorghe Andrei is a PhD Student at University of Bucharest and Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales Paris. His research interests include comparative analysis, social studies, local development, and case studies. He has authored a publication titled Discursive Strategies of a Populist Leader in 2020 Romanian Legislative Elections: The Rhetoric and Political Style of George Simion, which examines the rhetorical approaches of populist leaders in Romania.

Paper 2: The Application of the Concepts of ‘People’ and ‘Nation’ in Recent Political Developments in Germany: Theoretical Sensitivities and Their Implications for Democracy