Please cite as:

ECPS Staff. (2025). “ECPS Conference 2025 / Panel 2 — “The People” in the Age of AI and Algorithms.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). July 8, 2025. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00104

Panel II: “‘The People’ in the Age of AI and Algorithms” explored how digital technologies and algorithmic infrastructures are reshaping democratic life. Co-chaired by Dr. Alina Utrata and Professor Murat Aktaş, the session tackled questions of power, exclusion, and political agency in the digital age. Together, their framing set the stage for two timely papers examining how algorithmic filtering, platform capitalism, and gendered data practices increasingly mediate who is counted—and who is excluded—from “the people.” With insight and urgency, the session called for renewed civic, academic, and regulatory engagement with the democratic challenges posed by artificial intelligence and transnational tech governance.

Reported by ECPS Staff

As our technological age accelerates, democracy finds itself in an increasingly precarious position—buffeted not only by illiberal politics but also by opaque digital infrastructures that quietly shape how “the people” see themselves and others. Panel II, titled “The People in the Age of AI and Algorithms,” explored how artificial intelligence, social media, and digital governance are reconfiguring the foundations of democratic life. Far from being neutral tools, these technologies actively structure political subjectivity, reshape the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion, and deepen existing inequalities—often with little accountability.

This timely and incisive session of the ECPS Conference at the University of Oxford, held under the title “‘We, the People’ and the Future of Democracy: Interdisciplinary Approaches” between July 1-3, 2025, was co-chaired by Dr. Alina Utrata, Career Development Research Fellow at the Rothermere American Institute and St John’s College, Oxford University, and Professor Murat Aktaş from the Department of Political Science at Muş Alparslan University, Turkey. Together, they provided complementary perspectives that grounded the panel in both international political theory and real-world geopolitical shifts.

Dr. Alina Utrata opened the session by noting how technology corporations—many based in the United States and particularly in Silicon Valley—play a crucial role in shaping today’s political landscape. Referencing recent headlines such as Jeff Bezos’s wedding, she pointed to the growing entanglement between cloud computing, satellite systems, and global power dynamics. She emphasized the importance of discussing AI in this context, particularly given the intense debates currently taking place in academia and beyond. Her remarks framed the session as an opportunity to critically engage with timely questions about artificial intelligence and digital sovereignty, and she welcomed the speakers’ contributions to what she described as “these thorny questions.”

Professor Murat Aktaş, in his opening remarks, thanked the ECPS team and contributors, describing the panel topic as seemingly narrow but in fact deeply relevant. He observed that humanity is undergoing profound changes and challenges, particularly through digitalization, automation, and artificial intelligence. These developments, he suggested, are reshaping not only our daily lives but also the future of society. By underlining the transformative impact of these technologies, Aktaş stressed the importance of discussing them seriously in this panel.

The panel brought together two compelling papers that tackled these questions from interdisciplinary and intersectional perspectives. Dr. Luana Mathias Souto examined how digital infrastructures exacerbate gender exclusion under the guise of neutrality, while Matilde Bufano explored the political dangers of AI-powered filter bubbles and the rise of the “Broliarchy”—a new digital oligarchy with profound implications for democratic governance.

Together, the co-chairs and presenters animated a rich discussion about how emerging technologies are not only transforming democratic participation but also reshaping the very concept of “the people.”

Dr. Luana Mathias Souto: Navigating Digital Disruptions — The Ambiguous Role of Digital Technologies, State Foundations and Gender Rights

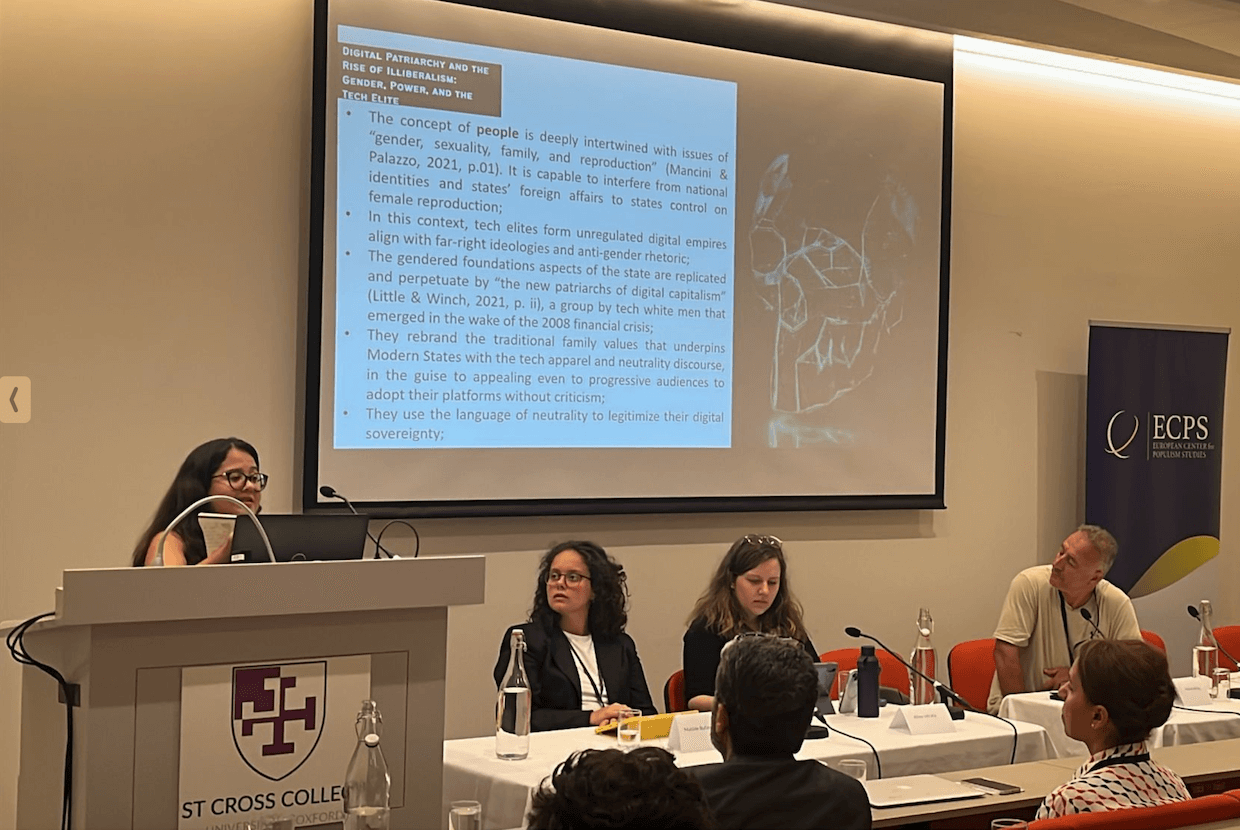

In her compelling presentation, Dr. Luana Mathias Souto, a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the GenTIC Research Group, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, examined how digital technologies—often framed as neutral tools of empowerment—are increasingly functioning as mechanisms for exclusion, surveillance, and patriarchal reinforcement, particularly against women. Her ongoing research critically interrogates how the foundational elements of statehood—sovereignty, territory, and people—are being redefined by the digital age in ways that intersect with illiberal ideologies and gender-based exclusion.

Dr. Souto opened by historicizing the exclusion of women from the category of “the people,” a structural pattern dating back centuries, and argued that this exclusion is not alleviated but rather exacerbated in the digital era. Drawing from feminist critiques and Global South scholarship, she explored how data flows and digital infrastructures decouple sovereignty from territoriality, complicating legal protections for individuals across borders. The concept of “digital sovereignty,” she noted, allows powerful private actors—particularly US-based tech giants—to co-govern people’s lives without accountability or democratic oversight. This dynamic renders traditional state functions increasingly porous and contested, especially in terms of enforcing regulations like the EU’s GDPR against surveillance practices rooted in the US legal and security regime.

Central to Dr. Souto’s argument is the idea that digital fragmentation not only challenges state sovereignty but also disrupts the cohesion of the political subject—the “people.” This fragmentation is manifested in what she called “divisible individuals,” where digital identities are reduced to segmented data profiles, often shaped by discriminatory algorithms. Despite the proclaimed neutrality of data, these systems encode longstanding social biases, particularly around gender. Dr. Souto emphasized how digital infrastructures—designed predominantly by male, white technocrats—perpetuate sexist norms and deepen women’s exclusion from political recognition.

She devoted particular attention to FemTech (female technology), highlighting apps that track menstruation, ovulation, and sexual activity. While marketed as tools of empowerment, Dr. Souto argued these technologies facilitate new forms of surveillance and control over women’s bodies. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade in the US, data from such apps have reportedly been used in criminal investigations against women seeking abortions. Similar practices have emerged in the UK, where antiquated laws are invoked to justify digital searches of women’s phones. Beyond legal threats, FemTech data has also been exploited in employment contexts, where employers potentially use reproductive data to make discriminatory decisions about hiring or promotions.

Dr. Souto linked these practices to broader alliances between tech elites and anti-gender, illiberal movements. By promoting patriarchal values under the guise of neutrality and innovation, tech companies offer a platform for regressive gender ideologies to take root. This fusion of technological governance with far-right agendas—exemplified by calls for “masculine energy” in Silicon Valley—is not incidental but part of a broader effort to rebrand traditional hierarchies within supposedly apolitical spaces.

In conclusion, Dr. Souto called for a fundamental challenge to the presumed neutrality of digital technologies. She argued that reclaiming democratic space requires recognizing how digital infrastructures actively shape who is counted as part of “the people”—and who is excluded. Without such critical engagement, the digital revolution risks reinforcing the very forms of patriarchal and illiberal governance it once promised to transcend.

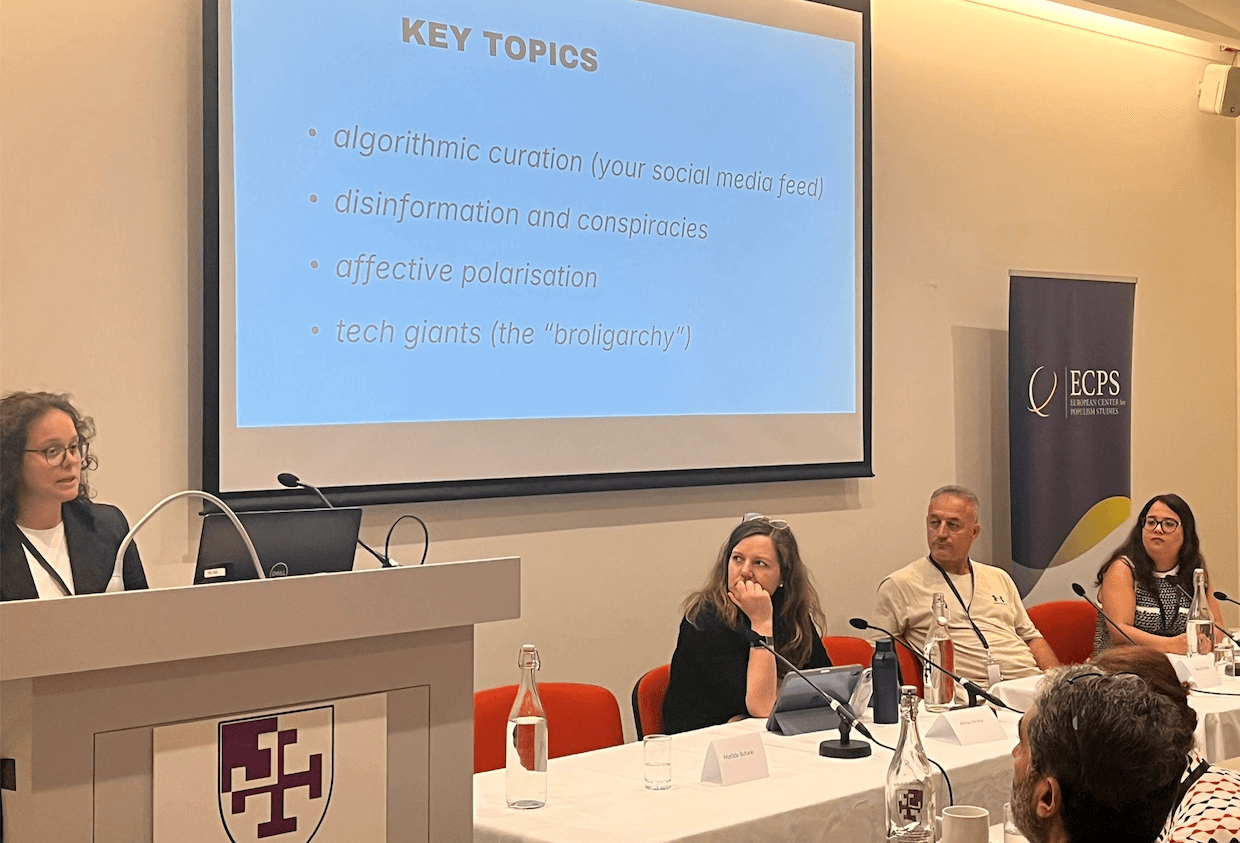

Matilde Bufano: The Role of AI in Shaping the People — Big Tech and the Broliarchy’s Influence on Modern Democracy

In a sobering and richly analytical presentation, Matilde Bufano, MSc in International Security Studies at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies and the University of Trento, examined the deeply intertwined relationship between artificial intelligence (AI), social media infrastructures, and the erosion of democratic norms in the age of Big Tech. Her paper, “The Role of AI in Shaping the People: Big Tech and the Broliarchy’s Influence on Modern Democracy,” offered a timely, practice-oriented reflection on how algorithmic technologies—far from being neutral tools—play a crucial role in shaping public consciousness, manipulating democratic engagement, and amplifying societal polarization. Drawing from her dual background in international law and digital politics, Bufano delivered a cross-disciplinary critique that challenged both policy complacency and academic detachment in the face of AI-driven democratic disruption.

At the heart of Bufano’s analysis lies a powerful assertion: democracy is not only threatened from outside by illiberal regimes or authoritarian populism, but also from within, through the algorithmic architecture of digital platforms that increasingly mediate how citizens engage with one another and with politics. The COVID-19 pandemic, according to Bufano, marked an inflection point. As physical interaction gave way to a digital public sphere, citizens became more dependent than ever on technology for information, identity, and even emotional validation. This shift coincided with an intensification of algorithmic curation, wherein AI systems selectively filter, promote, or suppress information based on user behavior and platform profitability.

Bufano focused on two key mechanisms underpinning this dynamic: algorithmic filtering and algorithmic moderation. Algorithmic filtering sorts through vast quantities of online content using coded preferences—ostensibly for user relevance, but in practice to optimize engagement and advertising revenue. This results in the formation of “filter bubbles,” echo chambers where users are continually exposed to like-minded content, reinforcing existing beliefs and psychological biases. Bufano distinguished between collaborative filtering—which groups users based on shared demographics or behavioral traits—and content-based filtering, which recommends material similar to what a user has previously interacted with. Both reinforce a feedback loop of ideological reinforcement, generating a form of identity-based gratification that discourages critical engagement and cross-cutting dialogue.

Crucially, this personalization is not politically neutral. Bufano demonstrated how algorithmic design often prioritizes sensationalist and polarizing content—particularly disinformation—because of its virality and ability to prolong user attention. Ninety percent of disinformation, she argued, is constructed around out-group hatred. In this context, algorithmically curated media environments deepen societal cleavages, producing a form of affective polarization that goes beyond ideological disagreement and encourages personal animosity and even dehumanization of political opponents. This is especially visible in contexts of crisis, such as during the pandemic, when scapegoating of Asian communities proliferated through local Facebook groups, or in the use of conspiracy theories and “phantom mastermind” narratives to channel social discontent toward imagined enemies.

The political consequences of this trend are severe. Filter bubbles inhibit democratic deliberation and increase susceptibility to manipulation by foreign and domestic actors. Bufano cited examples such as Russian disinformation campaigns in Romania, illustrating how AI-driven social media platforms can serve as conduits for election interference, especially when publics are already fragmented and mistrustful of institutions. These risks are magnified by a dramatic rollback in fact-checking infrastructures—most notably in the United States, where 80% of such systems were dismantled after Trump’s presidency, and mirrored in countries like Spain.

Bufano introduced the concept of the Broliarchy—a portmanteau of “bro” and “oligarchy”—to describe the growing political influence of a narrow cadre of male tech billionaires who control the infrastructure of digital discourse. No longer confined to private enterprise, these actors now exert direct influence on public policy and regulation, blurring the boundary between democratic governance and corporate interest. She illustrated this with the example of Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter (now X), which led to a 50% increase in hate speech within weeks due to weakened content moderation policies. Such developments, Bufano warned, compromise democratic accountability and entrench anti-democratic values under the guise of free expression and innovation.

While Bufano acknowledged the European Union’s recent steps toward regulation—especially the Digital Services Act (DSA), which seeks to promote transparency and safety in content recommendation systems—she emphasized the limitations of regional legislation in a global digital ecosystem. AI remains a “black box,” inaccessible to users and regulators alike. Without global accountability frameworks, national or regional efforts risk being outpaced by platform evolution and cross-border data flows.

In conclusion, Bufano made a dual appeal. First, for institutional and legal reforms capable of subjecting algorithmic systems to democratic oversight, including mandatory transparency in how recommender systems operate. Second, for renewed civic engagement and media literacy among citizens themselves. Democracy, she reminded the audience, cannot be fully outsourced to algorithms or regulators. It requires a culture of critical reflection and active participation—both online and offline. Reclaiming this space from the Broliarchy, she argued, means not only resisting disinformation and polarization, but reimagining democratic communication in ways that are inclusive, pluralistic, and resistant to both technological and ideological capture.

Bufano’s presentation, blending empirical insight with normative urgency, underscored the need for interdisciplinary collaboration in addressing one of the most urgent challenges of our time: how to ensure that digital technologies serve, rather than subvert, the democratic ideal.

Conclusion

Panel II of the ECPS Conference 2025, “The People in the Age of AI and Algorithms,” offered a powerful and urgent exploration of how digital infrastructures are reshaping the foundations of democratic life. As the presenters compellingly demonstrated, artificial intelligence, algorithmic governance, and platform capitalism are not passive tools but active agents that shape political subjectivities, influence public opinion, and determine who is included in or excluded from the category of “the people.” Across both presentations, a clear throughline emerged: digital technologies, while often framed in terms of neutrality and innovation, are in fact deeply embedded in structures of inequality, bias, and elite power.

Dr. Luana Mathias Souto illuminated how digital technologies intersect with patriarchal norms to undermine gender rights and state sovereignty, showing how the global tech ecosystem facilitates new forms of surveillance and control over women. Matilde Bufano, in turn, unpacked the algorithmic logic behind political polarization and democratic backsliding, naming the emergence of the “Broliarchy” as a key actor in this process. Together, their insights revealed a troubling paradox: while democracy should enable broad participation and dissent, the very platforms that now mediate political life often amplify exclusion and entrench concentrated power.

Rather than offering despair, the panel ended on a call to action. Both speakers urged the need for democratic oversight, global regulation, and enhanced digital literacy to reclaim public space and political agency in the algorithmic age. As AI technologies continue to evolve, so too must our frameworks for accountability, inclusion, and democratic resilience.

Note: To experience the panel’s dynamic and thought-provoking Q&A session, we encourage you to watch the full video recording above.