This commentary examines the tension between authoritarian populism and innovation-driven growth, drawing on the insights of Nobel laureates Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt. Their research highlights that sustainable prosperity relies on creative destruction, institutional openness, and freedom of inquiry. In contrast, authoritarian populism undermines these conditions by eroding pluralism, legal stability, and academic autonomy. Using comparative cases such as China, Turkey, Hungary, and Poland, Professor Ibrahim Ozturk shows how populist regimes politicize innovation systems, stifling long-term productivity. The essay concludes that innovation is not merely economic—it is institutional, cultural, and democratic. Without inclusive institutions and free knowledge systems, technological progress becomes extractive rather than transformative.

This commentary explores the fundamental tension between authoritarian populism and innovation-driven economic growth, drawing on the work of Nobel laureates Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt. These scholars emphasize the critical role of knowledge, institutions, and creative destruction in fostering sustainable growth. In contrast, authoritarian populism undermines these pillars by eroding institutional openness, pluralism, and policy stability. Combining their contributions with insights from economists like Acemoglu and North, this commentary underlines that technological progress without institutional freedom becomes extractive rather than transformative. Innovation, therefore, is not solely an economic process—it is profoundly institutional, cultural, and democratic.

Innovation Ecosystems and the Foundations of Long-Term Growth

The awarding of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics to Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt comes at a pivotal moment, as authoritarian populism gains ground globally, including in liberal democracies like the United States and across Europe. This recognition is more than an academic endorsement; it serves as a warning against the populist trajectory—and as a call to reaffirm the institutional foundations necessary for long-term, inclusive prosperity. Together, these laureates have transformed our understanding of how innovation drives growth and why it depends critically on inclusive, resilient institutions.

Joel Mokyr provides a historical and cultural framework, arguing that technological advancement arises not simply from material conditions, but from epistemic institutions—universities, protections for dissent, and a culture of inquiry that supports the creation and diffusion of knowledge. Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, meanwhile, formalized the process of innovation-led growth through their endogenous growth model, rooted in creative destruction. Their work illustrates how growth is generated when new technologies and firms continuously disrupt the old, enabled by competition, R&D investment, and enabling public policy. Their combined message is clear: Sustainable innovation cannot thrive without freedom of inquiry, legal stability, institutional independence, and competitive markets. When these are eroded, growth not only slows—it may become directionally regressive, channeling resources toward control rather than creativity.

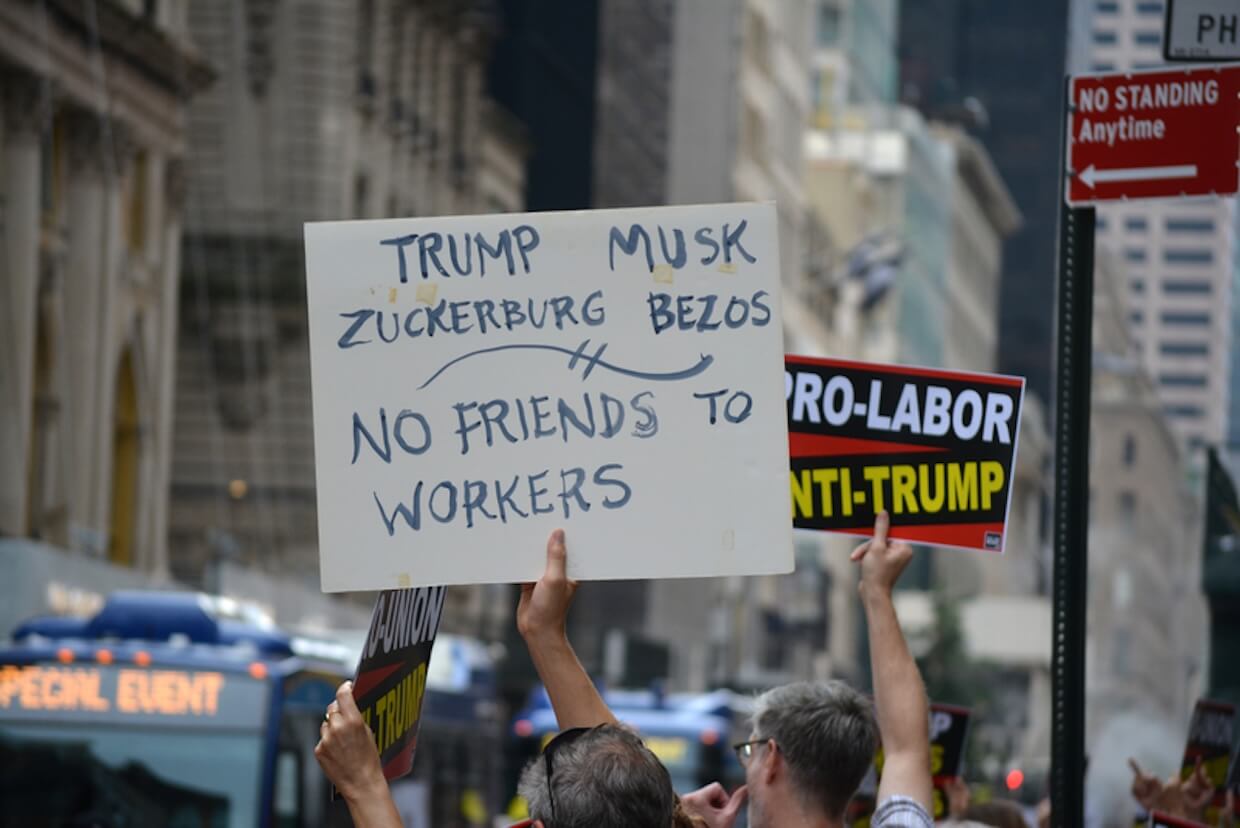

Authoritarian Populism and the Threat to Innovation Institutions

While the Nobel laureates underscore the importance of institutional infrastructure for innovation, the global rise of authoritarian populism presents a sharp countercurrent. Populism’s consolidation of executive power, erosion of checks and balances, and hostility toward expertise and dissent undermine the very systems that make innovation possible. This raises two fundamental questions: i) What can we learn from the intellectual legacy behind the 2025 Nobel Prize in an era of resurgent populism? ii) If our primary concern is sustainable and inclusive economic prosperity, what paths do the populist versus institutionalist frameworks each offer?

The answers lie in the institutional costs of populism. Populist regimes, as Rodrik (2019) explains, often emerge from economic discontent and cultural anxiety—but they typically respond by concentrating authority and limiting contestation. This instinct directly conflicts with the unpredictability and disruption inherent in innovation.

How Populism Damages the Mechanisms of Creative Destruction

Creative destruction, the engine of Aghion and Howitt’s growth model, is inherently destabilizing. It disrupts incumbents, transforms labor markets, and threatens established power structures—dynamics that populist regimes seek to resist. Though some argue that authoritarian populists could theoretically design innovation-friendly policies, empirical reality suggests otherwise. Populist leaders prioritize short-term visibility and control over long-term, uncertain processes like R&D. Consequently, megaprojects and state-industrial policies replace long-term innovation strategies. As Portuese (2021) notes, populists may even weaponize antitrust policy, using it to punish disloyal firms and protect politically connected monopolies—thereby cultivating a climate of fear and rent-seeking, not innovation. The erosion of judicial independence, university autonomy, and press freedom disables the feedback mechanisms essential for adaptive learning. As institutions hollow out, clientelist redistribution replaces competitive funding. Brezis and Young (2023) demonstrate how innovation systems under populist rule become politicized and inefficient, redirecting resources away from discovery and toward loyalty.

Empirical Evidence: Populism’s Innovation Deficit

Numerous case studies support this idea: China, despite its strong state capacity, faces innovation stagnation at the frontier due to censorship, limited peer review, and politically driven science (To, 2022). While China has made significant advances in frontier technologies—ranging from electric vehicles and green energy to artificial intelligence and quantum computing—this progress exists alongside growing structural barriers. Recent reports by the Financial Times (2024) and the World Bank (2023) highlight a widening gap between technological investment and productivity results, indicating that innovation has become increasingly state-led but not more efficient.

The politicization of science limited academic independence, and the expanding influence of party committees within universities and tech companies has hindered the creativity and openness necessary for frontier innovation. Although China has surpassed the United States and the EU in patent volume and some industrial technologies, its overall total factor productivity growth has slowed sharply since the late 2010s, meaning that technological accumulation is not leading to widespread productivity gains. As Foreign Policy (2025) analysis points out, China’s innovation model now risks “technological involution,” where large R&D spending only reproduces existing ideas rather than creating breakthroughs; in short, centralized control can mobilize resources on a large scale but also limits the institutional diversity and critical inquiry that are essential for true creative disruption.

The situation in Turkey, Poland, and Hungary, which exhibits highly strong populist authoritarian hybrid governance mechanisms, shows a similar trend. Turkey’s shift toward authoritarianism after 2011 reversed earlier gains in R&D and scientific output as scientific governance became politicized (Apaydin, 2025). In Hungary and Poland, Ágh (2019) finds that populist leaders systematically undermined institutional independence, leading to stagnation in innovation indices despite EU integration.

While Turkey’s R&D investment and publication output grew rapidly during the 2000s, the post-2011 erosion of academic autonomy—and particularly the post-2016 state-of-emergency decrees—triggered a systemic collapse in institutional freedom and international collaboration. Studies by the Freedom House (2023) and V-Dem Institute (2024) show Turkey’s academic freedom score falling to the bottom decile globally, coinciding with an 18–25% drop in publication activity and widespread self-censorship across universities. The World Bank (2023) further notes that this institutional degradation has curtailed the country’s innovation potential, as politicization redirected R&D spending from independent inquiry toward regime-aligned projects.

In Hungary, the Orbán government’s transformation of public universities into quasi-private “foundations” after 2020—where board members are appointed by the ruling Fidesz party—has drawn strong criticism from the European Commission (2022) and led to suspension of EU research funds under the Erasmus+ and Horizon Europe programs. According to the European Innovation Scoreboard (2024), Hungary remains a “Moderate Innovator,” showing stagnation or decline in scientific co-publications and R&D intensity.

Poland exhibits a similar trajectory: rule-of-law backsliding and politicization of the judiciary under the Law and Justice (PiS) government have weakened legal predictability and university independence. The Freedom House (2023) report documents a marked decline in judicial independence and civil liberties, while the European Innovation Scoreboard categorizes Poland as an “Emerging Innovator,” lagging behind EU averages in R&D expenditure and innovation outputs.

Collectively, these cases demonstrate that while state-led development under populist or illiberal regimes may yield short-term industrial gains, it ultimately erodes the very institutional foundations—autonomy, rule of law, and international openness—upon which decentralized, pluralistic, and experimental innovation systems depend.

Institutional Resilience and the Direction of Innovation

As Acemoglu and Johnson (2023) argue, innovation is not inherently progressive or welfare-enhancing. Its social impact depends on who funds it, controls it, and decides where it is applied. Under authoritarian populism, technological advancement often serves repression—surveillance, military tools, propaganda—rather than social welfare. By contrast, democratic and pluralistic systems encourage innovation aligned with public interest. Independent media, civil society, and open debate create a feedback-rich environment that improves allocative efficiency and mitigates risks.

Importantly, innovation ecosystems are not simply clusters of firms and labs—they are institutional configurations that support curiosity, tolerate failure, and reward experimentation. Where expression is free, laws are predictable, and academia is autonomous, breakthrough innovation thrives. Conversely, populist regimes undermine all three. Furthermore, their nationalist isolationism curtails international collaboration, peer review, and talent mobility—all of which are essential for frontier innovation, especially in an era of global challenges like climate change and pandemics.

Conclusion: Innovation Requires Democracy, Market, and Competition

The message from the 2025 Nobel Prize is unambiguous: Innovation is not merely an economic outcome—it is a political and institutional achievement. Prosperity does not arise from investment alone, but from the freedom to thought, challenge, and experiment. Where institutions collapse, innovation recedes. Where pluralism flourishes, discovery thrives.

Authoritarian populism, by closing civic space and concentrating power, not only compromises democratic legitimacy—it dismantles the very foundations of long-term economic growth. As Acemoglu and Johnson warn, without inclusive institutions, innovation becomes a tool of control—not of emancipation. Thus, the future of progress lies not only in laboratories or startups, but also in constitutions, courts, and universities. Any society that seeks prosperity through innovation must first protect these spaces.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2023). “Power and progress: Our thousand-year struggle over technology and prosperity.” Public Affairs. https://www.publicaffairsbooks.com/titles/daron-acemoglu/power-and-progress/9781541702093/

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). “A model of growth through creative destruction.” Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351. https://doi.org/10.2307/2951599

Ágh, A. (2019). Declining democracy in East-Central Europe: The divergence of Poland and Hungary. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788972157

Apaydin, F. (2025). “Repression and growth in the periphery of Europe.” Competition & Change, 29(2), 150–175. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/cch

Brezis, E. S., & Young, D. (2023). “Authoritarian populism and innovation.” Innovation and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2023.2205303

European Commission. (2022, December 22). Commission decides to request suspension of payments under Hungary cohesion programmes. https://commission.europa.eu/news/commission-decides-request-suspension-payments-under-hungary-cohesion-programmes-2022-12-22_en

European Commission. (2024). European innovation scoreboard 2024. https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/statistics/performance-indicators/european-innovation-scoreboard_en

Financial Times. (2024, May 15). “China’s innovation paradox.” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/b44458cc-03fd-46a1-b003-b7a097419e66

Foreign Policy. (2025, October 10). “China’s tech push and the risk of stagnation.” Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/10/10/china-tech-ai-innovation-economy-stagnation/

Freedom House. (2023). Freedom in the World 2023: Turkey. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2023/turkey

Freedom House. (2023). Freedom in the World 2023: Poland. https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/freedom-world/2023

Mokyr, J. (2002). The gifts of Athena: Historical origins of the knowledge economy. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691094830/the-gifts-of-athena

Nelson, R. R. (2017). “National innovation systems and institutional change.” Industrial and Corporate Change, 26(3), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtx015

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808678

Portuese, A. (2021). “Populism and the economics of antitrust”. In: M. Cavallaro & B. Moffitt (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of populism (pp. 845–866). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80894-0_39

Rodrik, D. (2019). Why does populism thrive? CEPR Policy Insight No. 100. https://cepr.org/publications/policy-insight/why-does-populism-thrive

Romer, P. M. (1990). “Endogenous technological change.” Journal of Political Economy, 98(5 Pt 2), S71–S102. https://doi.org/10.1086/261725

To, Y. (2022). Contested development in China: Authoritarian state and industrial policy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003206521

V-Dem Institute. (2024). Academic freedom index dataset v6. University of Gothenburg. https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/?country=223&indicator=acad_free

World Bank. (2023). China economic update: December 2023. World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/publication/china-economic-update-december-2023

World Bank. (2023). Turkey knowledge economy assessment. World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/turkey/publication/knowledge-economy-assessment