DOWNLOAD ARTICLE

Please cite as:

Mancin, Luca. (2025). “Doing Populism with Words: A Philosophical-Linguistic Clarification of Empty Signifiers’ Role in the Post-Laclauian Approach.” Populism & Politics (P&P). European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). August 04, 2025. https://doi.org/10.55271/pp0050

Abstract

This paper delves into the post-Laclauian approach to populism to offer a deeper theoretical and philosophical-linguistic analysis of empty signifiers within populist discourse. While the ideational approach has dominated recent scholarship by defining populism as a thin-centred ideology grounded in people-centrism, anti-elitism, and the general will, it has also been criticised for treating ‘the people’ as a homogenous monolith. In response, the post-Laclauian framework offers a more dynamic, discursive, and performative understanding of populism. However, this approach has insufficiently addressed the linguistic and pragmatic nature of empty signifiers so far. By examining the philosophical and semiotic foundations of empty signifiers throughout the works of Laclau, Lévi-Strauss, and Barthes, this article clarifies their role in the bi-directional construction of meaning between populist leaders and voters. Additionally, it argues that a clearer understanding of these signifiers is essential to grasp how populist messages resonate and are co-constructed from the demand-side. The paper concludes by outlining future directions for research, drawing especially on focus groups and quantitative text analysis to investigate empty signifiers in populist discourses further.

Keywords: populism; empty signifiers; post-Laclauian approach; performative politics; populist communication

By Luca Mancin

Research Problem and Background

Populism is today one of the most common, if not abused, words in the political realm (Brown & Mondon, 2021; Schwörer, 2021). In 2004, Mudde talked about a “populist Zeitgeist”, and the early 2000s coincided with a resurgence of works on populist empirical cases. Nevertheless, it is from the second decade of the 2000s that populism studies experienced a considerable number of publications (Rooduijn, 2019). The most widely accepted definition of populism is Mudde’s, who defines it as “an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (2004, p. 543).

This definition is central to the ideational approach that considers populism a ‘thin-centred ideology’. This approach highlights the three elements of people-centrism, anti-elitism, and the general will and frames the dichotomy between the people and the elite as moral (Hawkins et al., 2019; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018). However, scholars adopting the post-Laclauian approach have lately questioned the ideational one (Ostiguy et al., 2020). The latter depicts populist ‘the people’ as a homogenous community (Albertazzi & McDonnell, 2008; Betz & Johnson, 2004; Jansen, 2011; March 2017; Stanley, 2008) or a cohesive entity (Jagers & Walgrave, 2007; Taggart, 2000). The ideational approach to populism reveals the flexible and imaginative character of populist ‘the people’, as well as its ad hoc construction and supposed homogeneousness – making it a fictitious uniform group that cannot effectively include the entire citizenship.

This debate, however, is nothing new: from a political-philosophical standpoint, the ontological and political nature of ‘the people’ is an ever-lasting debate. During the French Revolution, the Count of Mirabeau stated that ‘the people’ “necessarily means too much or too little (…). It is a word that lends itself to everything” (Rosanvallon, 2002: 36). Accordingly, Pierre Rosanvallon represents ‘the people’ as a mysterious object whose features are not easily recognisable. While central to politics, ‘the people’ is nothing more than an assumption on which the exercise of popular sovereignty and the entire democratic system relies (Kelsen, 2018). To use Dubiel’s words, ‘the people’ is “like the ‘thing-in-itself’ of political theory” (1986: 80), that, like the Kantian Noumenon, is an imperceptible object per se, independent from human sensations and, therefore, unknowable. Thus, Rosanvallon writes that ‘the people’ is a Janus-faced entity: it is “both power and enigma: as power, it is the source of all legitimacy, as enigma it does not present an easily identifiable face” (2002: 36).

Building on these philosophical premises, the conceptualisation of ‘the people’ as an artificial homogeneity leads, according to Katsambekis (2022), to the homogeneity thesis, which risks producing rigid and aprioristic categorisation of populist actors. Ostiguy et al.’s (2020) post-Laclauian approach seems to overcome this problem by combining Laclau’s discursive approach to populism with the performative one and merging the former’s theoretical nature with the latter’s more empirical-oriented attitude. Indeed, scholars of the ideational approach postulate ‘the people’ as a homogenous socio-political construct in the definition of populism (Mudde, 2004; Taggart, 2004).

However, populist voters present different sociocultural backgrounds and diversified identities – as studies on these parties’ voters demonstrate (Akkerman et al., 2014; Inglehart & Norris, 2016; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, 2018). Treating ‘the people’ as a monolith would produce interpretational mistakes about populist parties and actors’ categorisation. On the contrary, ‘the people’ is multifaceted and protean and is always the product of contingent circumstances (Katsambekis, 2022). To make sense of the inner elements of Katsambekis’ critique of the homogeneity thesis and understand the post-Laclauian approach to populism and its focus on discourse and performativity, it is essential first to provide a brief sketch of the theoretical foundations of Laclau’s approach.

Laclau and Mouffe’s Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985) sets the philosophical-linguistic ‘guidelines’ of their constructivist discourse theory. According to their post-structuralist approach, meanings are not fixed but constantly redefined through social practices and struggles over discursive hegemony. As Torfing explains, “A discourse is a differential ensemble of signifying sequences in which meaning is constantly renegotiated” (1999: 85). A discourse becomes a ‘meaningful whole’ through articulation, connecting various elements into a unified framework. It can happen in two ways, as Laclau explains in On Populist Reason (2007): through a ‘logic of difference’ (i.e., stressing particularity and distancing it from other particularities based on a differential criterium) or through a ‘logic of equivalence’ (i.e., renouncing to a portion of that particularity to emphasise the commonalities those particularities share).

Within these chains of words, ‘nodal points’ construct the identity of a discourse by creating a network of interconnected meanings. Nodal points work as purely formal signifiers – that is, empty, floating, or overflowing signifiers (henceforth, I will refer to them as empty signifiers), words that can mean different things according to different persons (Chandler, 2007). Examples of nodal points are ‘God’, ‘Nation’, or ‘Class’, whose meaning depends on individuals’ opinions and beliefs or the discursive context. In concrete, nodal points retroactively define the identity of empty signifiers by integrating them into a coherent discourse (see Torfing, 1999).

Building on that, the post-Laclauian approach aims to study populism relationally, stressing the role of discourses and performative staging of populist leaders and supporters. Additionally, Ostiguy et al. (2020) question the moralist elements that, according to the ideational approach, would characterise populism (i.e., the anti-elitism and the dichotomy between the pure people and the corrupt elite). Similarly, they refuse the general will as the third distinctive trait of populism because populism “operates somewhere else, as a logic, as a kind of argument, as a rhetoric, or more broadly as a style or way in politics of stating, framing, and performing particular political projects” (2020: 3). Moreover, unlike the ideational one, the post-Laclauian approach provides a comprehensive outlook on populist strategic elements (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, 2017) and does not overlook the relationship between ideological construction and sociocultural dynamics (Stanley, 2008).

However, even though the post-Laclauian approach proposes a solid solution to deal with populism both as a discourse and a set of acts, it does not convincingly delve into the linguistic side of populist discourses and arguments. It does not clarify the linguistic nature and, consequently, the pragmatic role of empty signifiers in Laclau’s theory. While recent research has increasingly acknowledged the centrality of empty signifiers in populist rhetoric and empirically investigated these terms (Baloge & Hubé, 2022; Gruber et al., 2023; Sorensen, 2023; Zanotto et al., 2024; Zienkowski & Breeze, 2019) all these works focus on how leaders employ these signifiers (i.e., the supply side). Moreover, explaining these words’ role in the bi-directional identification process between populist leaders and supporters is under-researched and taken for granted from a philosophical-linguistic standpoint. Indeed, whilst from a performative perspective (Butler, 1988), populism consists of a set of acts and attributes (Canovan, 1984; Moffit, 2016; Ostiguy, 2017), what is missing is clarificatory and theoretical research on empty signifiers to highlight how their nature works in the populist identification process, with particular attention to the demand-side.

Thus, this paper theoretically elaborates on the post-Laclauian approach to populism to deepen the linguistic analysis of empty signifiers within populist communication. This article sets out the theoretical premises necessary to better understand how audiences interpret, negotiate, and co-construct the meanings of empty signifiers in populist discourses. The paper is structured as follows: First, I outline the theoretical foundations of the post-Laclauian approach. Next, I examine the bi-directional relationship between populist leaders and voters. Drawing on insights from pragmatics, I then explore the philosophical-linguistic nature of empty signifiers, referencing the works of Lévi-Strauss and Barthes. Finally, I conclude with suggestions for future research addressing the demand-side reception and co-construction of populist language between leaders and voters.

From Discourse to Pragmatic: What the Post-Laclauian Approach Leaves Unsaid

Ostiguy et al.’s (2020) post-Laclauian framework combines Laclau’s discursive approach with sociocultural and performative ones. By doing so, it stresses the logico-discursive dimension on the one hand and the sociocultural and stylistic dimension on the other.

The discursive approach to populism is traceable to Laclau’s (1977, 1980) early works on the topic and is fully elaborated in On Populist Reason (2007), drawing from Laclau and Mouffe’s (1985) theory. It investigates populism through discursive frameworks to illustrate populist claims and statements by examining the content rather than the form (Panizza & Stravakakis, 2020). According to Laclau (2007), populism represents a political logic entailing a series of unsolved socio-political demands which might link each other in a ‘chain of equivalence’ (relying on the above-mentioned logic of equivalence). Indeed, populism’s preconditions are 1) an inner frontier separating ‘the people’ and the Other, 2) a demands’ chain of equivalence highlighting the emergence of ‘the people’, and 3) the systematisation and unification of these demands through symbols (Laclau, 2007).

The etymological meaning of ‘symbol’ helps to understand Laclau’s idea of populism better: ‘Symbol’ derives from the Ancient Greek symbállo (‘to put together’, ‘to unite’). Communication (from the Latin communicare, ‘to put in common’) has a symbolic and connective nature. As discussed, this aspect is due to nodal points, the central elements of the chain of equivalence that allow understanding of what discourses deal with (Diez, 2001). Nodal points are “privileged discursive points that partially fix meaning within signifying chains”, creating “the identity of a certain discourse by constructing a knot of definite meanings” (Torfing, 1999: 98).

Therefore, nodal points are (and must be) accessible, familiar, and identifiable words or concepts used to mobilise the heterogeneous variety of individuals by acting as a mutual symbol. Recurrent nodal points in political discourses are words such as ‘God’, ‘homeland’, ‘class’, or ‘party’. However, nodal points can also be objects with a symbolic meaning, such as the umbrellas in Hong Kong protests, the yellow vests of the French Gilets Jaunes movement, the rainbow flag both for pacifism and LGBTQIA+ Community support, Javier Milei’s chainsaw, Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again (MAGA) red hat, or the Guy Fawkes mask from the movie V for Vendetta (McTeigue & the Wachowskis, 2005). All these words and icons are used to mobilise different socioeconomic and political demands around them and combine different needs in a homogenous political struggle. However, at the same time, they also manage to convey wider and various meanings through a simple name or image.

Accordingly, Torfing explains, “the conception of nodal points reveals the secret of metaphors: their capacity to unify a certain discourse by partially fixing identity of its moments” [1] (1999: 99). Again, the etymology of ‘metaphor’ is crucial to grasp the nature of populist communication: ‘Metaphor’ stems from the Ancient Greek metaphéro (i.e., ‘to carry’, ‘to transfer’). In metaphors, the meaning is transferred from one realm to another, as in the statement, “Smart as a whip”. Thus, metaphors also consist of the linguistic capacity to produce an image of reality that is much more ductile than reality itself (Martinengo, 2016) since it forces to analogise a speech element (‘smart’) with an element that is inconsistent with the speech context (‘whip’).

Concerning populist communication, the most recurrent nodal point is ‘the people’ (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, 2017; Katsambekis, 2022). In this article, I will use ‘the people’ as the main example, but the same reasoning can be made for other populist nodal points (e.g., ‘homeland’, ‘nation’, ‘sovereignty’, ‘freedom’, ‘family’, ‘gender’, or ‘justice’). ‘The people’ is used by populist leaders as an immediately recognisable word around which they build their party’s narrative. “The signifier ‘the people’ operates here as a nodal point, a point of reference around which other peripheral and often politically antithetical signifiers and ideas can be articulated” through a dynamic process (Panizza & Stavrakakis, 2020, p. 25). Thus, populism polarises society into two factions: “a dichotomic division between unfulfilled social demands, on the one hand, and an unresponsive power, on the other” (Laclau, 2007, p. 86). These unanswered and unapproached citizens’ claims produce a chain of dissent, which needs to be amalgamated around some similarities (i.e., the chain of equivalence) and polarise against an external enemy (the Other, usually the government).

However, the construction of ‘the people’, Laclau (2007) says, does not happen in a vacuum but relies on a set of performative repertoires, strengthening a broad sense of the group’s unity and cohesion (Moffitt, 2016). Accordingly, Canovan considers populism “a matter of style” (1984, p. 314) and, besides verbal and metaphorical elements (messages, us-versus-them rhetoric, and body language), also focuses on non-written communicative aspects (implications, allusions, irony, and gestures) and aesthetics (staging, symbolism, clothes, and slang). All these elements have primarily in common the appeal to ‘the people’ and seek to mobilise voters, polarise the debate in a dichotomic manner, and create a relationship between the leader and the electorate (Aalberg et al., 2016; Kazin, 2017; Knight, 1998). Generally, despite differences in the content’s framing of populist communicative style, these categorisations share the populist leaders’ attempt to forge a new identity among voters by calling into being the category of ‘the people’ through rhetorical techniques (Moffitt & Tormey, 2014).

Ostiguy (2017) works specifically on this bi-directional approach to populism by illustrating the sociocultural dimension of its support and reception. Populist success is not exclusively due to a top-down relation, in which a charismatic leader mobilises and bewitches the masses; it also consists of a bottom-up dynamic through which the voters identify themselves with the leader. While focusing on populist performance and praxis as the stylistic approach does, the novelty of the sociocultural outlook is the assumption of a political high-low axis. According to Ostiguy, the high consists of well-mannered, elegant, rationalist, and acculturate politicians who speak a cold policy and legislative language and are distant from the citizenry. By contrast, the low refers to politicians who use a language full of slang, folksy expressions, metaphors and vulgar gestures, wear comfortable and casual clothes, and present themselves as ordinary individuals like the members of their electorate.

‘The people’ image and identity result from a bi-directional and synthetical operation between leaders and voters. On the one hand, the leader advances instances in the name of a certain ‘the people’; on the other hand, those voters who are expected to embody such entity can accept, modify, or reject these instances (Ostiguy & Moffit, 2020). In other words, the identity of ‘the people’ is not imposed from the top by the leader but stems from a twofold elaboration involving voters participating in their collective identity formation. This combination of discursive, sociocultural, and stylistic approaches has the benefit of anchoring Laclau’s theory to concrete populist dynamics by giving ‘the people’ a political agency and clarifying how and why the identification process between leaders and voters works (Ostiguy & Moffit, 2020).

Then, voters have an active role in dealing with the leaders’ construction of ‘the people’, which entails a bi-directional relationship and produces a two-way echo discourse (Panizza, 2017). Still, to be effective, the two poles of the continuum (the leader and the voters) must develop a sense of belonging and construct a ‘we-ness’ by emphasising negative differences with the out-group (‘them’) and positive similarities within the in-group (‘us’). Given the mix of different subgroups constituting ‘the people’, populist leaders attempt to forge a cohesive image of it by appealing to its vague and general nature. Hence, according to the post-Laclauian approach, populism is a way of ‘doing politics’ that a) generates an us-versus-them dynamic and b) actively constructs identities through affective investments and symbolism (Herkman, 2017; Palonen, 2018).

This process is quite evident from Butler’s (1988) visual, performative perspective since specific manners, gestures, clothes, or settings (Canovan,1984; Moffit, 2016; Ostiguy, 2017) work as identity-making acts and performances. Butler explains that a repetition of acts institutes the identity because performing a specific set of attributes constitutes the identity that those attributes say to express. However, despite these advances, the post-Laclauian framework still lacks a clear account of how language itself – beyond symbols and performances – operates in populist discourse. There are several studies on populism with a pragmatic approach, but they always adopt a visual performative outlook (Casullo, 2020; Ekström et al., 2018; Kissas, 2020; Palonen, 2019; Volk, 2020).

The post-Laclauian still does not examine how specific terms become effective political signifiers through meaning-generation and listener inference processes. This gap calls for investigating empty signifiers in populist rhetoric, particularly from the demand-side perspective. Hence, in the next section, I intend to do so by looking at the branch of the philosophy of language known as pragmatics, which investigates, beyond a statement’s literal meaning, the meaning related to what a speaker intends to say.

Pragmatics and Implicit Language: A Cooperative Activity

Pragmatics deals with the relationship between speakers and linguistic signs and what individuals aim to do with language as a social and communication tool (Bianchi, 2003). Individuals speak not only to describe the world’s facts; language also entails a series of practical implications (Morris, 1938). For instance, if I state, “It is raining”, I am describing a natural phenomenon, but I might also suggest to my friend to take an umbrella. Therefore, pragmatics focuses on analysing the implicit meaning of a message and a speaker’s intention and always requires an understanding of context (i.e., interlocutors’ identities and shared knowledge, linguistic co-text, and spatiotemporal coordinates).

Pragmatics mainly deals with ambiguity, deixis, and figurative language, which entail using implicit language. Indeed, in all these cases, the speaker does not convey all the information, and the statement’s meaning is not entirely clear. Consequently, the interlocutor must ‘interpret’ that by relying on the context. However, implicit language is essential; otherwise, our language would be too wordy and cumbersome, and every communication would be too time-consuming. For example, if I tell my friend, “Go downstairs and close the door, please”, I am implicitly informing her that there is an open-door downstairs (something that she probably already knows from the context, and I do not need to repeat).

The British philosopher Herbert Paul Grice (1975) explained the mechanisms of implicit language through the theory of implicature. The theory relies on the Principle of Cooperation, a series of four maxims that reflect the expectations each of us has when participating in a conversation. These maxims are of quantity, quality, relation, and manner and require the speakers, during communication, to be informative, truthful, relevant, and clear, respectively. This principle implies that all participants contribute to communication according to the discourse’s purposes and orientation.

Hence, every utterance has two meanings: the expression’s (i.e., the literal meaning) and the speaker’s (i.e., the speaker’s intention, which implies an interpretative process). The speaker’s meaning, as said, is often implicit, and Grice (1975) calls it implicature – which can be conversational or conventional. For instance, I ask my friends, “Are you coming to the stadium?” and they answer, “We are working”. Their answer is not literal but implies they cannot go to the stadium because of their work. I must draw the implicature based on my knowledge of the world (i.e., when individuals are working, they cannot do something else). Besides the value of the linguistic economy and the chance to have interpersonal communication, implicit language also plays a pivotal role in persuasion. Indeed, implicit statements convey messages that bypass epistemic vigilance and critical thinking more easily than explicit ones (Lombardi Vallauri, 2019).

Consequently, implicit language is used as an in-group identity marker in political communication by emphasising dichotomic rhetoric (Cominetti et al., 2023; Sbisà, 2007). Simple examples are proposed by Lombardi Vallauri (2019), analysing Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia 2006 electoral campaign. On some of his electoral posters were the following statements: “Do we stop major works projects? No, thank you” and “Illegal immigrants at will? No, thank you”. These declarations announce an adverse scenario – no public investments and more illegal immigrants – and Forza Italia simply positions against them. However, these claims also suggest – and citizens elaborate that from them – Berlusconi’s adversaries will pursue those measures if they win. Another strategy to exploit implicit language for political purposes consists of using common names such as ‘migrants’ or ‘homosexual’ to convey cliches, as these words generate stereotyped and oversimplified images in the listeners’ minds (Lakoff, 1987; Levinson, 2000; Putnam, 1975). After all, since implicit language rests on close and necessary cooperation between interlocutors, one speaker may use ambiguous terms to persuade the other. Therefore, common names strategically exploit their vagueness as they are accepted more readily and subjected to lower critical scrutiny.

Something similar happens with imprecise and non-specified statements that may refer to several entities or objects. It is particularly evident with terms known as deictic expressions (e.g., ‘here’, ‘now’, ‘this’, or ‘that’) or for placeholder words(e.g., ‘democracy’, ‘freedom’, or ‘justice’) that change meaning according to context and listeners (Ophir, 2018). As said, all deictic expressions have a concrete reference only within a context, and it is appropriate to make semantic use of it to grasp their meaning (Bianchi, 2003). When dealing with intentional deixis used for descriptions or demonstrations, they (can) create ambiguity. To fully grasp the meaning, one always needs an indication from the speaker unless the interlocutor shares prior knowledge gained from the context (e.g., I say “That” and point to it with my finger if we have not talked about the said object yet).

Advertisements use the same mechanism: consider the claim “Paradise Island Hotel: experience the best in Acapulco” from Lombardi Vallauri (2019). ‘Experience the best’ will have several meanings or mental connotations depending on individuals’ experiences, tastes, and beliefs. Due to its vagueness, the statement allows everyone to interpret and react to that personally. As a result, the same message leads to several, and potentially opposite, outcomes. It happens the same with the two examples from Forza Italia given above. ‘Major works projects’ and ‘At will’ are vague and imprecise because they are deliberately unspecified so that voters can ascribe to these expressions whichever meaning they want to and fill them depending on their opinions, beliefs, and experiences.

The parallels between implicature, strategic vagueness, and political placeholders lead us back to the concept of the empty signifier. In populist discourse, these signifiers are effective precisely because their meaning is open to personal inferences and interpretations, allowing each listener to make their own associations. Empty signifiers are thus not mere rhetorical tools but real pragmatic acts of co-construction of meaning. Now, populism is known for its wide use of strategic vagueness (Mény et al., 2002) since it recurs to several placeholders, such as ‘God’, ‘homeland’, ‘class’, or ‘party’, as Laclau (2007) explains. Ambiguity is unavoidable if not even necessary for populism: “The language of a populist discourse – whether of Left or Right – is always going to be imprecise and fluctuating […] because it tries to operate performatively within a social reality which is to a large extent heterogeneous and fluctuating” (p. 118). Therefore, populist communication can achieve the same goals of statements like “Paradise Island Hotel: experience the best in Acapulco” or “Illegal immigrants at will? No, thank you” (Lombardi Vallauri, 2019). Voters interpret populist leaders’ (deliberately vague) words as they want and always find a way to identify with them (if needed).

However, the more the identification with a nodal point is extended, the more the precision of this identity is impoverished because it is too generic and vague. A concrete example from language is deictic expressions like ‘here’, ‘now’, ‘this’, or ‘that’: they can indicate everything, but the precision of their ‘identification’ of a specific object decreases. Consequently, in populist discourses, the nodal point is often an empty signifier (Laclau, 2007), as it must be flexible and ambiguous enough to encompass different meanings to unify various questions and construct a collective identity. Empty signifiers are malleable and adaptable to various sociocultural, political, and economic situations. They are defined as signifiers “with a vague, highly variable, unspecifiable, or non-existent signified. Such signifiers mean different things to different people: they may stand for many or even any signifieds; they may mean whatever their interpreters want them to mean” (Chandler, 2007: 78).

In pragmatics, implicit language requires the listener’s proactive participation in the speaker’s words to grasp the meaning. Similarly, I argue that empty signifiers require the recipients to fill the void with their own, often implicit, meaning for their role as linguistic glue to work. This aspect is precisely what the post-Laclauian approach has taken for granted, even though it adequately explains the bi-directional linkage between the leader and the supporters from a communicative standpoint. This work is the same cooperative one that the speaker and listener establish when the former does not convey all the information, and the latter must ‘interpret’ the message based on the context. As seen, however, context consists of linguistic and extralinguistic elements. Therefore, to fully understand the mutual construction of identity between leaders and voters, it is worth analysing not only the visual and performative aspects of populism but also its linguistic core. In what follows, I examine how empty signifiers function pragmatically and what their nature reveals about the dynamics of populist identification from a voter-centred perspective.

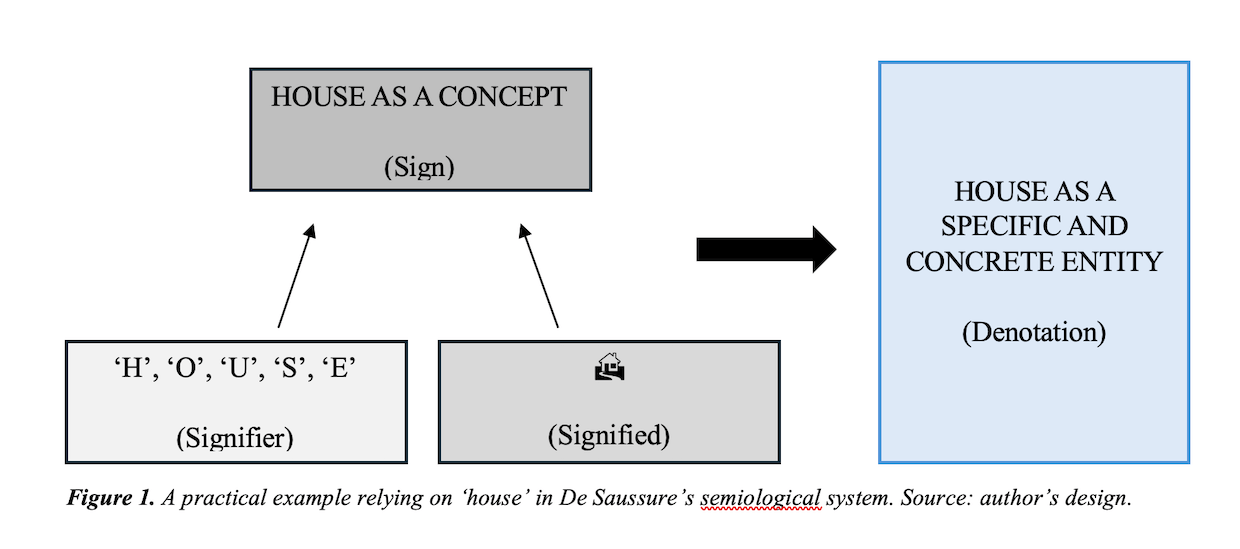

Empty Signifiers: A Philosophical-Linguistic Detour

It is worth starting from de Saussure’s (2011) work to understand empty signifiers’ linguistic nature. The Saussurean structural linguistic theory first entails the distinction between language and speech. Language (or langue) is the social element of linguistic dynamics and relies on structures, codes, and social rules linked to a specific community (Bernstein, 1964). Language also composes the conditions of possibility of the speeches (or paroles), which instead represent the individual, creative, and singular aspects of speaking and writing expressing personal thoughts and feelings. Thus, the language is not a scheme which allows speakers to label objects and things with their names. Conversely, each linguistic sign is the product of a combination of a signified (i.e., the mental concept: the abstract image we have of a specific object) and its signifier (i.e., the acoustic image: the reaction produced by the physical existence of the object in the form of written or spoken word) (see Figure 1).

In de Saussure’s system, the sign ‘house’ (a conventional and arbitrary word) unifies an acoustic image (the signifier: the letters composing ‘house’) with a specific mental concept (the signified: the mental and personal image of ‘house’) (Chandler, 2007; Torfing, 1999). Thus, the signified and the signifier are mutually tied: they are inseparable, but their relationship is arbitrary. Indeed, speakers can express the same meaning through different signifiers – both in translations and via periphrasis or synonyms. For de Saussure, this arbitrariness is an unmotivated and unnecessary behaviour where the chimaera of empty signifiers thrives (Chandler, 2007). For this reason, the scheme in Figure 1 does not apply to empty signifiers, as the research of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes shows.

In the Introduction to the Work of Marcell Mauss (1987), Lévi-Strauss describes the words ‘man’ and ‘hau’ as empty signifiers. Mana and hau must be considered as words that per se do not mean anything concrete and specific, but that can be used for everything, such as, in English, the already mentioned deictic expressions ‘the thing’, ‘that’, or ‘something’. Lévi-Strauss’ research stems from the symbolic dimension of language, according to which symbols are more concrete than the objects they depict. This happens because, as shown, a symbol conveys a broader abstract meaning than the object that materially composes it. In these cases, de Saussure’s (2011) framework is subverted, and the signifier precedes and determines the signified; namely, the acoustic image produces the mental concept. Thus, mana and hau are “the subjective reflection of the need to supply an unperceived totality” (Lévi-Strauss, 1987: 58).

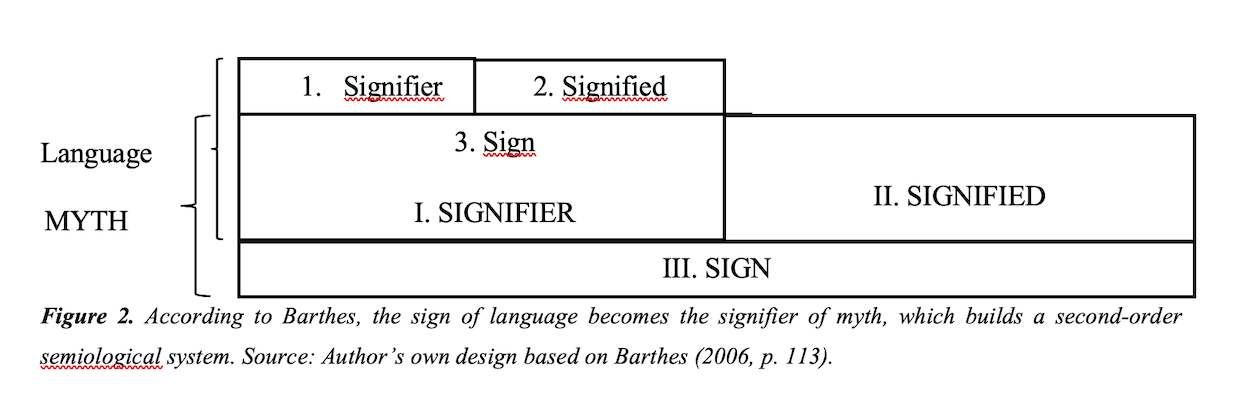

According to Barthes’ Myth Today (2006), mythical constructions are discourses relying on a peculiar semiological system. In Barthes’ works, ‘myths’ are all those narratives that offer an extra level of reading than the literal one – so propaganda or advertising, for example, also fall into this category. In myths, the relationship between the signifier, the signified, and the sign is still present; however, contrary to de Saussure’s (2011) idea that the sign is the mediation between the signified and signifier, Barthes considers myths as a “second order semiological system” (p. 128). Accordingly, the sign in the first order becomes a signifier in the second one (see Figure 2). Then, it is crucial to distinguish between denotation and connotation. Denotation is a sign’s direct and ‘literal’ meaning, while connotation is a personal association of images or meanings (based on sociocultural background, emotions, or beliefs) to the sign (Chandler, 2007). To put it in Fiske’s words, “Denotation is what is photographed; connotation is how it is photographed” (1990: 86). Thus, Barthes (2006) states that the first semiological order coincides with denotation, while the second is the connotation level. Therefore, in Barthes, connotation and mythical dimensions overlap.

Consider the example of a white dove: the denotation is the bird per se, while its connotation is the symbol of peace accompanying the image of a white dove in the popular imagination. The sign/signifier has two faces: one whole, the meaning in the linguistic order, and the other empty on the mythical level. This double semiological system is particularly evident in advertising and propaganda, as a famous example by Barthes (2006) also shows. One day, he says, on the cover of the Paris Match, there was a black soldier with a French military uniform – and this is the linguistic sign of the first order. The mythical second order signifier conveys messages about the great French Empire, where everyone – regardless of ethnicity and background – is treated equally, and there is no such thing as oppressing colonialism.

Hence, myth is “a double system” (Barthes, 2006: 121), led more by a communicative intention than by its literal meaning. “The signifier of myth presents itself in an ambiguous way: it is at the same time meaning and form, full on one side and empty on the other” (Barthes, 2006: 116). This emptiness and vagueness are what Lévi-Strauss (1987) highlights in mana and hau and in their attempt to represent totality. However, in mythical speeches, the aim is different and concerns a distortion and a deformation. Accordingly, Barthes states: “If I focus on the mythical signifier as on an inextricable whole made of meaning and form, I receive an ambiguous signification: I respond to the constituting mechanism of myth, to its own dynamics” (Barthes, 2006: 127).

Populist recurrent terms such as ‘the people’, ‘homeland’, ‘family’, or ‘gender’ function as empty signifiers not only because they are strategically vague but because they activate deeply embedded connotative associations shaped by personal, cultural, and emotional experiences. Much like Lévi-Strauss’s (1987) mana or Barthes’ (2006) mythic signs, their linguistic power lies not in literal reference but in their capacity to unify heterogenous meanings into a single affective node. Therefore, understanding populism requires us to investigate not only what is said but also how audiences interpret and acknowledge it.

Beyond the Signifier: Toward a Voter-centred Linguistic Turn in Populism Studies

Building on the previous sections, two core insights emerge: the fluidity and resignification of populist empty signifiers and the co-creation of their meaning in a dialogic process between leaders and audiences. As discussed, empty signifiers are not simply vague labels or stylistic choices, but they work as sites of meaning negotiation, anchored in context, speaker intention, and listeners’ interpretation. Then, it is clear why Ostiguy and Moffit maintain that “discursive acts do not ‘stand alone’ (…) but must also resonate with the lived experiences and social encounters experienced in daily life” (2020:53). On the one hand, empty signifiers unite populist discourse, and their effectiveness lies in strategic ambiguity, allowing them to serve as affective, symbolic vessels for various political demands (Mény et al., 2002). On the other hand, populism relies on a top-down relation (i.e., the leader charming the voters) but also a bottom-up dynamic (i.e., the voters’ identification with the leader) (Ostiguy, 2017).

While political leaders deliberately use vague words, their acceptance and resonance depend on the voters. It implies that meaning is co-created through a dialogic process where leaders and followers play an active role. Thus, voters are not to be considered passive recipients of political messages; instead, they interpret, accept, reject, or modify the meanings proposed by leaders. This dialogic nature occurs in visual and verbal symbols mentioned above that serve as nodal points in contemporary populism: Javier Milei’s chainsaw, the Guy Fawkes mask, the yellow vest, or Trump’s MAGA hat. Some symbols are imposed from above and circulate vertically, while others rise from spontaneous protest and are retrospectively adopted by leaders. Their power stems from symbolic condensation in both cases: they unify diverse grievances through emotionally charged, easily recognisable forms.

Dealing with a timely example, MAGA simultaneously operates as a visual icon (e.g., Trump’s red hat), a political brand, and what de Saussure has termed an acoustic image – a signifier that produces a concept in the listener’s mind. For some voters, MAGA may convey images of national pride or economic resurgence; for others, it might entail nativism or cultural exclusion. As shown in the previous sections, the MAGA’s success lies precisely in its malleability: its ability to function as a symbol filled with various – and sometimes contradictory – meanings.

This growing interest in populist discourse has led to a wave of empirical studies investigating how leaders articulate empty signifiers across various contexts. Scholars like Katsambekis (2022), Sorensen (2023), and Gruber et al. (2023) have shown how terms such as ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ are strategically filled with different content by left- and right-wing populist parties. On their side, Baloge and Hubé (2022) highlight how Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Marine Le Pen deploy ‘the people’ with different connotations – pluralist and civic on one side, ethnic and exclusionary on the other. Similarly, Zanotto et al. (2024) apply a computational-linguistic approach to track how Italian populist parties shift the emotional charge and thematic associations of empty signifiers over time. These studies converge on a key insight: the meaning of empty signifiers is contextual, dynamic, and politically constructed.

Nevertheless, while these contributions are valuable, they all focus on the supply side. They analyse what political actors say, how they frame key terms, and how symbols are deployed in speeches or campaigns. What remains underdeveloped is the interpretive labour of audiences: how voters understand, fill, resist, or reshape these empty signifiers. This lack is especially remarkable, given how central the idea of identification is in both Laclauian and post-Laclauian theory. If, as Laclau (2007) argues, populism succeeds by unifying disparate demands into a chain of equivalence, then understanding how audiences interpret those demands is just as crucial as understanding how leaders articulate them. Some studies investigate voters and citizens, but they rely on pre-defined categories of populist content or leader’s traits rather than allowing audiences to define their interpretations of populist signifiers (Akkerman et al., 2014; Milner, 2021; Rooduijn, 2018; Spruyt et al., 2016; Voogd & Dassonneville, 2020). In these works, voters are typically profiled – demographically, psychologically, economically, or attitudinally – but not investigated as ‘meaning-makers’. As a result, the co-constructive nature of populist discourse remains methodologically underexplored. A partial exception to this common practice is the work by Şahin et al. (2021), which explores how targeted groups interpret and respond to populist discourse and empty signifiers.

To address this gap, I think it is necessary to conduct more research on populism in political psychology. This approach can only be helpful because it is poorly employed within populism studies, as Rovira Kaltwasser (2021) claims. More specifically, I believe qualitative research may help develop new studies on the fluidity and resignification of populist empty signifiers and the co-creation of their meaning from a voter-centred perspective. For instance, throughout focus groups (Kitzinger, 1994; Morgan, 1997) it would be possible to understand how voters from different parties react or interpret various empty signifiers and how these interpretations influence their political choices and vary among parties’ bases. Just as performative acts are a constant ‘confirmation’ of a said identity (Fischer-Lichte, 2008), the co-interpretation of empty signifiers’ meanings and consequences should be seen as a reiterated choice to adhere to and support a particular party. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how voters perceive empty signifiers, how they react to them, and which emotional reactions these words trigger. If scholars do not explore this second and fundamental side of the bi-directional linkage between leaders and voters, the risk is treating populism as a solipsistic practice without fully grasping its dynamics.

The theoretical basis for this turn is grounded in pragmatics and semiotics, as discussed in previous sections. Just as the meaning of a deictic expression like ‘here’ or ‘now’ depends on context, a term like ‘the people’ depends on who is saying it, when, and to whom. Nevertheless, this approach has potential limitations when applying these philosophical-linguistic elements to empirical research. I showed that empty signifiers rest on a post-structuralist and semiotic theory whose concepts are not operationalizable into clear-cut indicators or variables. Moreover, empty signifiers are highly context-sensitive and relational, a characteristic that makes it difficult to detect and measure them in empirical data through qualitative methodologies. Consequently, any empirical application of this framework must proceed cautiously and, as Zienkowski and Breeze (2019: 4) emphasise, focus on in situ analyses (i.e., carefully considering each country’s cultural, socioeconomic, and political context). Therefore, any investigation relying on focus groups while offering valuable insights must account for the instability and fluidity of empty signifiers.

However, recent advances in computational discourse analysis and machine learning may allow researchers to overcome these limitations and complement a focus-group approach by mapping patterns of ambiguity and resonance. For instance, using word embedding models like word2vec or BERT may detect signifiers with high semantic variance by tracking how key populist empty signifiers – e.g., ‘the people’, ‘family’, ‘class’, ‘gender’, or ‘nation’ – shift in meaning across ideological contexts or over time (see Mostfavi et al., 2024; Stöhr, 2024). On its side, topic modelling (see Choi, 2025) can uncover themes around empty signifiers to detect which topics are mainly associated with them. If these terms are ‘empty’, they should show high semantic drift over time, polysemy across ideological clusters, and ambiguity in co-occurring contexts – all of which can be empirically measured. However, these tools are not sufficient on their own: computational models identify patterns, not meanings; they can suggest that ‘the people’ or ‘gender’ is used differently by left and right populists, but they cannot explain why or how these differences matter for identification and political behaviour. That task still belongs to interpretive, qualitative inquiry. Still, machine learning can help track their contextual fluctuations and audience-specific interpretations at scale, especially when integrated with qualitative data from focus groups.

A mixed-methods approach is therefore essential: focus groups can reveal the interpretive logic through which individuals assign meaning to ambiguous political terms, while computational models can then scale up those insights, showing whether the patterns observed in small groups hold across broader populations and media environments. This combination respects the contextual, relational nature of populist language while expanding the empirical reach of discourse analysis. It also opens new possibilities for comparative work. For instance, new research might investigate how empty signifiers travel across national, ideological, or linguistic boundaries. New studies could also explore how they mutate or stabilise in times of crisis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, populism studies would theoretically and methodologically benefit from incorporating the voter’s interpretive role into the study of populist discourse. Additionally, this approach would allow populism scholars to avoid the trap of reductionism (i.e., treating populism as a fixed set of traits, ideologies, or leader personalities) by focusing instead on the flexibility, affective power, and communicative negotiation that sustain it. As the philosopher John Langshaw Austin (2009) reminds us, we do things with words. In populism, words do things: they mobilise, exclude, and unify. Doing populism with words means engaging in a collaborative linguistic process that constantly shapes and reshapes collective identities and political allegiances – as long as one investigates both poles of demand and supply.

References

Aalberg, T.; Esser, F.; Reinemann, C.; Stromback, J., & De Vreese, C. (Eds.). (2016). Populist Political Communication in Europe. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315623016

Akkerman, A.; Mudde, C. & Zaslove, A. (2014). “How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters.” Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1324-1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

Albertazzi, D. & McDonnell, D. (Eds.). (2008). Twenty-First Century Populism. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230592100

Austin, J. L. (2009). How to do things with words: The William James lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Harvard University Press.

Barthes, R. (2006). Mythologies. Hill and Wang.

Baloge, M., & Hubé, N. (2022). “How populist are populist parties in France? Understanding parties’ strategies within a systemic approach.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 9(1): 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2021.2016455

Bernstein, B. (1964). “Elaborated and Restricted Codes: Their Social Origins and Some Consequences.” American Anthropologist, 66(6), 55–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/668161

Betz, H. & Johnson, C. (2004). “Against the current-stemming the tide: The nostalgic ideology of the contemporary radical populist right.” Journal of Political Ideologies, 9(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356931042000263546

Bianchi, C. (2003). Pragmatica del linguaggio [Pragmatics of language] (1st ed). GLF editori Laterza.

Brown, K., & Mondon, A. (2021). “Populism, the media, and the mainstreaming of the far right: The Guardian ’s coverage of populism as a case study.” Politics, 41(3), 279–295.

Butler, J. (1988). “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519–531. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893

Canovan, M. (1984). “‘People’, Politicians and Populism.” Government and Opposition, 19(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.1984.tb01048.x

Casullo, M. E. (2020). “Populism as Synecdochal Representation. Understanding the Transgressive Bodily Performance of South American Presidents.” In: P., Ostiguy, F., Panizza, B., Moffitt (Eds.), Populism in Global Perspective (pp. 75-94). Routledge.

Chandler, D. (2007). Semiotics: The basics (2nd ed). Routledge.

Choi, J. (2025). “Evolving populist rhetoric: how public approval shapes its employment.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2025.2491400

Cominetti, F.; Cimmino, D.; Coppola, C.; Mannaioli, G. & Masia, V. (2023). “Manipulative impact of implicit communication: A comparative analysis of French, Italian and German political speeches.” Linguistik Online, 120(2), 41–64. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.120.9716

De Cleen, B. & Stavrakakis, Y. (2017). “Distinctions and Articulations: A Discourse Theoretical Framework for the Study of Populism and Nationalism.” Javnost – The Public, 24(4), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083

Diez, T. (2001). “Europe as a Discursive Battleground: Discourse Analysis and European Integration Studies.” Cooperation and Conflict, 36(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/00108360121962245

Dubiel, H. (1986). “The Specter of Populism.” Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 31, 79–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41035375

Ekström, M.; Patrona, M. & Thornborrow, J. (2018). “Right-wing populism and the dynamics of style: a discourse-analytic perspective on mediated political performances.” Palgrave Communications, 4(83), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0132-6

Fischer-Lichte, E. (2008). “Explaining concepts. Performativity and performance.” In: E. Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance: A new aesthetics (pp. 24–29). Routledge.

Fiske, J. (1990). Introduction to communication studies (2nd ed). Routledge.

Grice, H. P. (1975). “Logic and Conversation.” In: P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (Eds.), Speech Acts (pp. 41–58). BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004368811_003

Gruber, M.; Isetti, G.; Ghirardello, L. & Walder, M. (2023). “Populism in Times of a Pandemic: A Cross-Country Critical Discourse Analysis of Right-Wing and Left-Wing Populist Parties in Europe.” Populism, 6(2), 147-171. https://doi.org/10.1163/25888072-bja10049

Hawkins, K. A.; Carlin, R. E.; Littvay, L. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (Eds.). (2019). The ideational approach to populism: Concept, theory, and analysis. Routledge.

Herkman, J. (2017). “Articulations of populism: The Nordic case.” Cultural Studies, 31(4), 470–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2016.1232421

Inglehart, R. & Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2818659

Jagers, J. & Walgrave, S. (2007). “Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium.” European Journal of Political Research, 46(3), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

Jansen, R. S. (2011). “Populist Mobilization: A New Theoretical Approach to Populism.” Sociological Theory, 29(2), 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2011.01388.x

Katsambekis, G. (2022). “Constructing ‘the people’ of populism: A critique of the ideational approach from a discursive perspective.” Journal of Political Ideologies, 27(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2020.1844372

Kazin, M. (2017). The populist persuasion: An American history. Cornell University Press.

Kelsen, H. (2018). Due saggi sulla democrazia in difficoltà: (1920-1925) [Two essays on democracy in trouble: (1920-1925)]. Aragno.

Kissas, A. (2020). “Performative and ideological populism: The case of charismatic leaders on Twitter.” Discourse & Society, 31(3), 268-284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926519889127

Kitzinger, J. (1994), “The methodology of Focus Groups: the importance of interaction between research participants.” Sociology of Health & Illness, 16, 103-121.

Knight, A. (1998). “Populism and Neo-Populism in Latin America, Especially Mexico.” Journal of Latin American Stuies, 30(2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/158525

Laclau, E. (2007). On populist reason. Verso.

Laclau, E. (1977). “Towards a theory of populism.” In: E. Laclau (Ed.), Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory. New Left Books.

Laclau, E. (1980). “Populist Rupture and Discourse.” Screen Education, 34(Spring), 87–93.

Laclau, E. & Mouffe, C. (1985). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics. Verso.

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, Fire and Dangerous Things. The University of Chicago Press.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1987). Introduction to the work of Marcel Mauss. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Levinson, S. (2000). Presumptive Meanings: The Theory of Generalized Implicatures. MIT Press.

Lombardi Vallauri, E. (2019). La lingua disonesta: Contenuti impliciti e strategie di persuasione [Dishonest language: Implicit content and strategies of persuasion]. Il Mulino.

March, L. (2017). “Left and right populism compared: The British case.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(2), 282–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117701753

Martinengo, A. (2016). Filosofie della metafora [Philosophies of metaphor] (1st ed). Guerini scientifica.

McTeigue, J. & The Wachowskis (2005). V for Vendetta [Film]. Silver Pictures, Virtual Studios, Studio Babelsberg, Vertigo DC Comics, Anarchos Productions, Inc.

Meléndez, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2019). “Political identities: The missing link in the study of populism.” Party Politics, 25(4), 520-533. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817741287

Mény, Y.; Surel, Y.; Tame, C. & De Sousa, L. (Eds.). (2002). Democracies and the populist challenge. Palgrave.

Milner, H. V. (2021). “Voting for Populism in Europe: Globalization, Technological Change, and the Extreme Right.” Comparative Political Studies, 54(13), 2286-2320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414021997175

Moffitt, B. (2016). The global rise of populism: Performance, political style, and representation. Stanford University Press.

Moffitt, B. & Tormey, S. (2014). “Rethinking Populism: Politics, Mediatisation and Political Style.” Political Studies, 62(2), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12032

Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Sage.

Morris, C. W. (1938). “Foundations of the theory of signs.” In: Otto Neurath et al. (Eds.). International encyclopedia of unified science, Vol. I, No.2, (pp. 1-59). The University of Chicago Press.

Mostafavi, M.; Porter, M.D. & Robinson, D.T. (2024). “Contextual Embeddings in Sociological Research: Expanding the Analysis of Sentiment and Social Dynamics.” Sociological Methodology, 55, 25-58.

Mudde, C. (2004). “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Mudde, C. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). “Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda.” Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1667–1693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018789490

Ophir, A. (2018). “Concept.” In: J.M. Bernstein, A. Ophir, & A.L. Stoler (Eds.), Political concepts: A critical lexicon (pp. 59-86). Fordham University Press.

Ostiguy, P. (2017). “Populism: A Socio-Cultural Approach.” In: C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. O. Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism (pp.73-97). Oxford University Press.

Ostiguy, P.; Panizza, F. & Moffitt, B. (Eds.) (2020). Populism in Global Perspective. Routledge.

Ostiguy, P. & Moffit, B. (2020). “Who Would Identify with an “Empty Signifier”? The Relational, Performative Approach to Populism.” In: P. Ostiguy, F. Panizza, & B. Moffitt (Eds.), Populism in Global Perspective. A Performative and Discursive Approach (pp. 47-72). Routledge.

Palonen, E. (2018). “Performing the nation: The Janus-faced populist foundations of illiberalism in Hungary.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 26(3), 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2018.1498776

Palonen, E. (2019). “Rhetorical-Performative Analysis of the Urban Symbolic Landscape: Populism in Action.” In: T., Marttila (Ed), Discourse, Culture and Organization. Postdisciplinary Studies in Discourse (pp. 179-198). Palgrave Macmillan.

Panizza, F. (2017). “Populism and Identification.” In: C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. O. Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism (pp. 516-539). Oxford University Press.

Panizza, F. & Stavrakakis, Y. (2020). “Populism, Hegemony, and the Political Construction of “The People. A Discursive Approach.” In: P., Ostiguy, F., Panizza, B., Moffitt (Eds.), Populism in Global Perspective (pp. 21-46). Routledge.

Putnam, H. (1975). Mind, Language, Reality. Cambridge University Press.

Rosanvallon, P. (2002). Le peuple introuvable: Histoire de la représentation démocratique en France [The Untraceable People: A History of Democratic Representation in France]. Gallimard.

Rooduijn M. (2018). “What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties.” European Political Science Review, 10(3), 351-368. doi:10.1017/S1755773917000145

Rooduijn, M. (2019). “State of the field: How to study populism and adjacent topics? A plea for both more and less focus.” European Journal of Political Research, 58(1), 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12314

Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2021). “Bringing political psychology into the study of populism.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 376(1822), 20200148. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0148

Şahin, O.; Vegetti, F.; Korkut, U.; Bobba, G.; Mancosu, M.; Seddone, A.; Stępińska, A.; Bennett, S., Lipiński, A.; Sotiropoulos, D.; Tsatsanis, M.; Mitsikostas, A.; Árendás, Z.; Messing, V.; Hubé, N. & Baloge, M. (2021). “Citizens’ reactions to populism in Europe: how do target groups respond to the populist challenge?” Democratic Efficacy and the Varieties of Populism in Europe – Working Paper, 1-23.

Saussure, F. de (2011). Course in general linguistics. Columbia University Press.

Sbisà, M. (2007). Detto non detto: Le forme della comunicazione implicita [Unspoken: The forms of implicit communication]. Laterza.

Schwörer, J. (2021). The Growth of Populism in the Political Mainstream. The Contagion Effect of Populist Messages on Mainstream Parties’ Communication. Springer.

Sorensen, L. (2023). “Populist disruption and the fourth age of political communication.” European Journal of Communication, 39(1), 71-85. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231231184702

Spruyt, B.; Keppens, G. & Van Droogenbroeck, F. (2016). “Who Supports Populism and What Attracts People to It?” Political Research Quarterly, 69(2), 335-346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912916639138

Stanley, B. (2008). “The thin ideology of populism.” Journal of Political Ideologies, 13(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569310701822289

Stöhr, F. (2024). “Advancing language models through domain knowledge integration: a comprehensive approach to training, evaluation, and optimization of social scientific neural word embeddings.” Journal of Computational Social Science, 7, 1753–1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-024-00286-3

Taggart, P. A. (2000). Populism. Open University Press.

Taggart, P. (2004). “Populism and representative politics in contemporary Europe.” Journal of Political Ideologies, 9(3), 269–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356931042000263528

Torfing, J. (1999). New theories of discourse: Laclau, Mouffe, and Z̆iz̆ek. Blackwell Publishers.

Van Hauwaert, S. M. & Van Kessel, S. (2018). “Beyond protest and discontent: A cross‐national analysis of the effect of populist attitudes and issue positions on populist party support.” European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 68–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12216

Volk, S. (2020). “‘Wir sind das Volk!’ Representative Claim-Making and Populist Style in the PEGIDA Movement’s Discourse.” German Politics, 29(4), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2020.1742325

Voogd R. & Dassonneville, R. (2020). “Are the Supporters of Populist Parties Loyal Voters? Dissatisfaction and Stable Voting for Populist Parties.” Government and Opposition, 55(3), 349-370. doi:10.1017/gov.2018.24

Zanotto, S.E.; Frassinelli, D. & Butt, M. (2024). “Language Complexity in Populist Rhetoric.” ACM Cyber-Physical System Security Workshop.

Zienkowski, J., & Breeze, R. (2019). Imagining the Peoples of Europe. Populist discourses across the political spectrum. John Benjamins Publishing Company

[1] Emphasis added.