Please cite as:

ECPS Staff. (2025). “ECPS Conference 2025 / Panel 7 — ‘The People’ in Schröndinger’s Box: Democracy Alive and Dead.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). July 9, 2025. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00109

In 2025, democracy occupies a state of superposition—at once vibrant and eroding, plural and polarized, legal and lawless. Panel 7 exposed this paradox with precision: democracy is not a fixed ideal but a shifting terrain, where power is contested through law, ritual, narrative, and strategy. Whether it survives or collapses depends on how it is interpreted, performed, and defended. The Schrödinger’s box is cracked open, but its contents are not predetermined. As Robert Person warned, authoritarian actors exploit democratic vulnerabilities; as Max Steuer and Justin Attard showed, those vulnerabilities also reveal possibilities for renewal. We are not neutral observers—we are agents within the experiment. Democracy’s future hinges on our will to intervene.

Reported by ECPS Staff

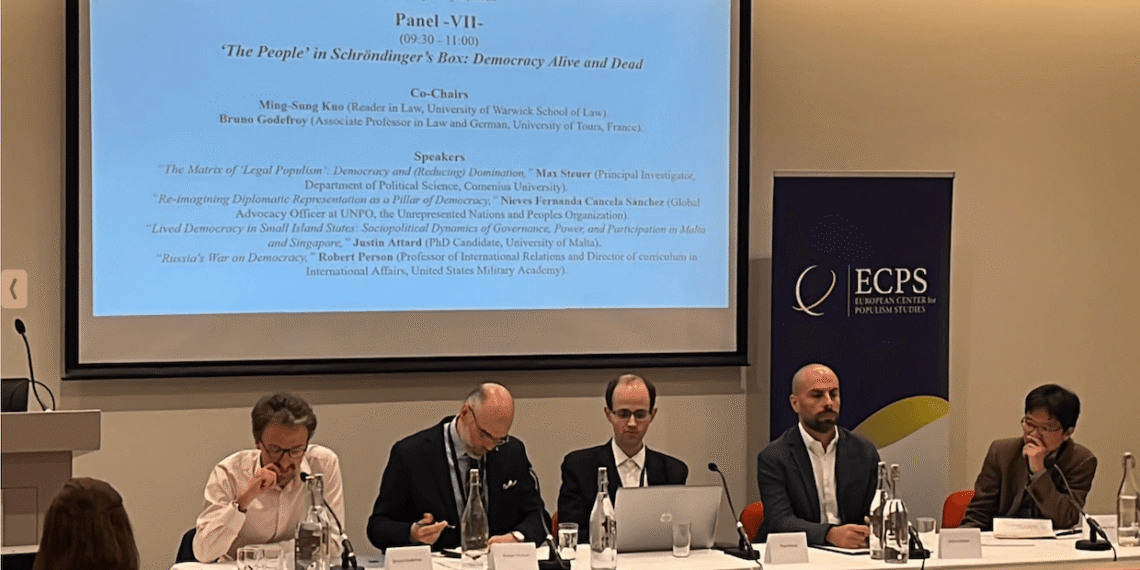

Panel 7 of the ECPS Conference 2025, held at the University of Oxford’s St Cross College, convened under the theme “‘The People’ in Schrödinger’s Box: Democracy Alive and Dead.” As part of the broader conference titled “We, the People” and the Future of Democracy: Interdisciplinary Approaches (July 1–3, 2025), this panel examined the paradoxical condition of democracy in our time—simultaneously enduring and unraveling, vibrant and hollow.

Skillfully co-chaired by Dr. Ming-Sung Kuo (Reader in Law, University of Warwick School of Law) and Dr. Bruno Godefroy (Associate Professor in Law and German, University of Tours, France), the session set out to interrogate how democratic systems today oscillate between vitality and decay, depending on how they are enacted, contested, or undermined. The Schrödinger’s box metaphor provided a conceptual anchor for discussions that unfolded across disciplines, cases, and levels of analysis—from legal theory to ethnographic inquiry to geopolitical grand strategy.

Dr. Max Steuer (Comenius University) opened the session with his presentation “The Matrix of ‘Legal Populism’: Democracy and (Reducing) Domination.” Dr. Steuer introduced a four-quadrant typology for understanding how populism interacts with conceptions of law—either as neutral instruments or aspirational forces—and illustrated its application through empirical material from Slovakia. His matrix illuminated how law may serve either as a shield for pluralism or a tool for authoritarian entrenchment, depending on who wields it and for what purpose.

Next, Justin Attard (University of Malta) presented “Lived Democracy in Small Island States: Sociopolitical Dynamics of Governance, Power, and Participation in Malta and Singapore.” Attard shifted the focus from institutional architecture to embodied democratic practice. In small island states where political proximity is inescapable, democratic participation becomes highly visible, affective, and often entangled in informal networks. Through the metaphor of democracy in superposition, Attard argued that democracy in such settings only becomes real when performed—through gestures, rituals, resistance, or silence.

Finally, Professor Robert Person (United States Military Academy) delivered a geopolitically urgent paper titled “Russia’s War on Democracy.” Positioning democracy itself as a target of Russian grand strategy, Professor Person detailed how asymmetric tactics—from disinformation and cyberwarfare to the cultivation of populist movements—form a central part of the Kremlin’s effort to weaken democratic resilience globally. His presentation reframed the defense of democracy as a strategic imperative in an increasingly contested international order.

Collectively, Panel 7 brought together three distinct yet converging perspectives on democracy’s condition in 2025. Whether examined through the legal system, the intimacy of everyday political life, or the ambitions of autocratic powers, democracy appeared both resilient and vulnerable—very much alive and under threat. As the co-chairs emphasized in their concluding reflections, this session not only invited critical observation but also urged active engagement with the layered realities of democratic life in an age of disruption.

Max Steuer: The Matrix of ‘Legal Populism’: Democracy and (Reducing) Domination

In his thought-provoking presentation, Dr. Max Steuer, Principal Investigator at Comenius University’s Department of Political Science, dissected the uneasy relationship between law and populism, offering a conceptual matrix—tentatively called a typology—for understanding what he terms “legal populism.” Delivered during Panel 7 of the ECPS Conference at Oxford University, Dr. Steuer’s paper draws from both political theory and empirical insights from Slovakia to explore how law can be weaponized or reimagined in democratic and anti-democratic contexts.

From the outset, Dr. Steuer acknowledged the terminological ambiguity surrounding populism, confessing a general reluctance to engage with the term unless conceptually necessary. In this case, however, the invitation to contribute to a volume on "legal populism" compelled him to interrogate the term seriously. Rather than offering a definition, he opted to analyze populism in relation to two contrasting conceptions of law—thereby creating a four-quadrant matrix.

Dr. Steuer’s conceptual framework rests on two axes: (1) law as either a neutral tool (instrumental view) or as inherently justice-seeking (aspirational view), and (2) populism as either a democratizing force (challenging domination) or as inherently anti-pluralist and authoritarian. These contrasting understandings allow for four different permutations of law-populism interaction: (a) legal populism as extralegal resistance, (b) populist legalism as authoritarian entrenchment, (c) strategic litigation in defense of pluralist elites, and (d) pro-social populism using law to redistribute power downward.

To illustrate the matrix, Dr. Steuer turned to the Slovak case—a jurisdiction he argued has been overlooked but is critical to understanding the spread of illiberalism in Central Europe. Slovakia, an EU and NATO member, experienced early post-socialist authoritarian tendencies under Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar in the 1990s, only to witness a re-emergence of populist authoritarianism in the 2020s under Robert Fico. Dr. Steuer noted that this resurgence follows a pattern resembling Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, although it includes earlier signs of institutional manipulation during the pandemic era under an ostensibly anti-corruption administration.

Dr. Steuer then mapped recent Slovak political events onto his matrix. The quadrant where law is seen as neutral and populism as anti-elite aligns with extralegal resistance—where, for instance, whistleblowers disclosed suspicious financial transactions of politicians at great personal legal risk. This quadrant represents rare but significant moments when actors violate the law to expose deeper systemic corruption, reflecting a logic of civil disobedience.

The second, more prevalent quadrant, which Dr. Steuer called “populist illegality” (borrowing yet problematizing the term “autocratic legalism” from Kim Scheppele), involves using legal frameworks to suppress opposition, undermine NGOs, and weaken epistemic communities like courts and universities. This aligns with populism‘s anti-pluralist tendencies and the instrumental use of law to entrench domination—a hallmark of authoritarian populist regimes.

In the third quadrant, where law is seen as justice-seeking and populism is viewed negatively, Dr. Steuer located practices such as strategic litigation and civic suits used to defend pluralist elites—e.g., legal efforts by opposition parties or civil society to counter disinformation or protect institutional integrity. In this scenario, law remains a protective shield for democracy rather than a populist weapon.

The final and most speculative quadrant—“legal populism” in its positive form—imagines using the law to challenge elite domination on behalf of the socially marginalized. This includes legal reforms aimed at redistributing welfare, expanding access to healthcare and education, or regulating oligarchic power. Dr. Steuer noted that this version of legal populism remains largely aspirational in Slovakia, though theoretically plausible.

Dr. Steuer’s framework is deeply informed by republican theory, particularly the notion of domination as unaccountable power. He reflected on the need to further interrogate whether the term “legalism” is appropriate or whether it conflates the normative and instrumental uses of law. He also acknowledged the preliminary nature of his matrix, inviting critique and refinement, especially concerning its applicability beyond Slovakia.

One of the most compelling parts of Dr. Steuer’s talk was his engagement with the paradox of legality in authoritarian regimes. As legal tools are increasingly employed to shield undemocratic practices under the guise of constitutionalism, the line between legality and illegality becomes blurred. Dr. Steuer stressed the importance of resisting the temptation to cede the terrain of legality to authoritarian regimes and instead reimagine law as a space for contesting domination.

He concluded by returning to the notion of oligarchic control—a structural threat he sees as central to Slovakia’s democratic erosion. Dr. Steuer called for further research into how oligarchic power can be challenged not merely through resistance or protest, but through law itself—as a forum for both democratic struggle and anti-domination.

In sum, Dr. Max Steuer’s presentation offered a nuanced, theoretically rich, and empirically grounded typology for analyzing the variegated intersections of populism and law. His “matrix of legal populism” helps illuminate how law can serve as both a vehicle for authoritarian entrenchment and a battleground for democratic renewal, depending on how it is deployed and by whom. By grounding his framework in the Slovak case while inviting broader application, Dr. Steuer made a valuable contribution to the comparative study of legal populism in contemporary democracies under strain.

Justin Attard: Lived Democracy in Small Island States: Sociopolitical Dynamics of Governance, Power, and Participation in Malta and Singapore

In his compelling presentation, Justin Attard, a PhD candidate at the University of Malta, offered a unique ethnographic exploration of democratic practice in small island states, focusing on Malta and Singapore. Attard’s paper advanced an innovative conceptual framework of “lived democracy,” emphasizing the embodied, relational, and performative dimensions of democratic life in compact political environments. Shifting away from conventional, institutional analyses of democracy, Attard invited the audience to reconsider how democracy is experienced, enacted, and felt through everyday behaviors, rituals, and silences—especially in societies where spatial proximity and dense social ties intensify the visibility and affective weight of political engagement.

At the heart of Attard’s argument lies the metaphor of democracy in “superposition,” drawn from Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment. Much like the cat that is simultaneously alive and dead until observed, democracy in small states can exist in both resilient and eroded forms—only collapsing into a defined state through the actions and experiences of citizens. Institutions may exist on paper, but in small island societies, democracy becomes tangible only when individuals participate, comply, resist, or remain silent. In such contexts, the observer is never passive; observation is itself participation, and every political act—no matter how minor—carries disproportionate symbolic and material significance.

To flesh out this theoretical claim, Attard juxtaposed the cases of Malta and Singapore. Both are nominally democratic: they hold elections, maintain constitutions, and adhere to parliamentary governance structures. However, their democratic substance often deviates sharply from their formal architecture. In Malta, democratic life is characterized by deeply entrenched clientelism, where political engagement is transactional and structured by interpersonal networks. Access to services and opportunities is often mediated through personal loyalty rather than merit or civic deliberation. In this sense, populism in Malta manifests through emotionally charged performances, symbolic gestures, and the informal economies of favor and proximity.

In contrast, Singapore presents a model of choreographed civic participation. Participation exists, but it is regulated and largely ritualized. Dissent is not wholly forbidden, but it is subtly discouraged through social expectations and mechanisms of internalized discipline. Public harmony is prioritized over contestation, and state-sponsored performances—such as National Day parades—serve to reinforce a tightly controlled, technocratic nationalism. Populism here is not loud or emotional, but managerial and procedural, embedded in state-led displays of order and unity. The comparison between Malta and Singapore challenges the assumption that populism must always be bombastic or oppositional. In small states, Attard argued, populism can also be quiet, embodied, and compliant.

Attard’s contribution also illuminates how scale alters the experience of democracy. In small island states, political life is hyper-visible and intensely personal. Citizens often know their representatives personally, and acts of political expression—whether a handshake at a rally or a conspicuous absence from a public event—are closely watched and socially consequential. Proximity collapses the boundary between public and private spheres, making political participation inseparable from social identity. These dynamics are especially pronounced in Malta, where kinship and neighborhood ties shape political affiliations, and in Singapore, where civic behavior is calibrated according to highly codified norms of belonging.

The theoretical underpinnings of Attard’s argument draw from Amanda Machin’s work on embodied democracy and Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence. These frameworks suggest that power does not reside solely in institutions or formal mechanisms but also in the internalized behaviors and affective dispositions of citizens. In this view, democracy is not just a philosophical ideal or legal condition—it is a lived, sensory, and relational experience. It is performed in gestures of loyalty, acts of resistance, and even in silence. Thus, democracy’s vitality cannot be measured solely by institutional indicators; it must be evaluated through its enactment in daily life.

Importantly, Attard cautioned against viewing Malta and Singapore as democratic failures. Instead, he argued, they represent variations in how democracy is lived and understood. In both contexts, the form of democracy remains intact, but its substance is negotiated through informal practices that often undermine equality, pluralism, and participatory depth. These states do not defy democratic norms outright; they hollow them out through ritualization, instrumentalization, and emotional detachment.

Attard concluded by emphasizing the analytical potential of studying small island states. Their compactness offers a “high-resolution lens” for observing the micro-dynamics of democracy—making visible the everyday acts that sustain or erode democratic life. While such phenomena might be diffused or abstract in large democracies, in small states, they are immediate, legible, and profoundly consequential. By foregrounding the embodied and relational dimensions of political participation, Attard’s presentation challenged the audience to move beyond binary notions of democracy and authoritarianism, and instead ask: how is democracy lived, and by whom?

In sum, Justin Attard’s presentation was a powerful invitation to reimagine the terrain of democratic inquiry. By centering lived experience, embodied practice, and relational proximity, he offered both a critique of institutional reductionism and a roadmap for future research on political life in small states and beyond.

Robert Person: Russia’s War on Democracy

In his presentation at the ECPS Oxford Conference 2025, Robert Person, Professor of International Relations and Director of Curriculum in International Affairs at the United States Military Academy, delivered a penetrating and strategically grounded analysis titled “Russia’s War on Democracy.” Drawing from his broader scholarly work on Russia’s grand strategy, Professor Person argued that undermining democracy—both domestically and abroad—has not been a peripheral concern for the Kremlin but a core pillar of Russia’s strategic doctrine under Vladimir Putin.

From the outset, Professor Person framed Russia’s multi-decade campaign as a deliberate, multifront war on democratic governance that transcends traditional ideological confrontation. According to Professor Person, Russia’s actions are best understood not as episodic reactions to geopolitical events, but as the orchestrated implementation of a grand strategy—a coordinated and adaptive approach for achieving long-term national objectives with finite resources.

In outlining the core logic of grand strategy, Professor Person defined it as the systematic alignment of national interests, strategic objectives, and the mobilization of resources and instruments of statecraft to shape an international environment conducive to a state’s goals. Russia’s grand strategy, he posited, centers on five key goals: (1) restoring Russia as a global great power, (2) replacing unipolarity with a multipolar order (envisioned as tri-polar with the US, Russia, and China), (3) securing exclusive influence over post-Soviet space, (4) re-establishing a 19th-century-like "Concert of Powers" in which great powers dominate global decision-making, and (5) counterbalancing the United States and its democratic allies, perceived as existential adversaries.

What makes this strategic vision especially paradoxical, Professor Person emphasized, is Russia’s relatively limited economic and military resources compared to its primary rivals. Russia’s GDP, even adjusted for purchasing power parity, lags far behind that of the United States and China. Thus, in contrast to conventional “additive” balancing strategies—such as military build-up or alliance formation—Moscow has adopted what Professor Person described as “asymmetric balancing.” Rather than attempting to match the West’s capabilities, Russia focuses on subtracting from its adversaries’ strategic coherence and political resilience. In this context, democratic vulnerability becomes a strategic opportunity.

Professor Person contended that democracies, by virtue of their pluralistic and open nature, present exploitable fissures. These include contentious political cleavages, ethnic tensions, institutional constraints, and electoral volatility. Russia has adeptly weaponized these vulnerabilities through what Professor Person termed asymmetric methods—a diverse toolkit encompassing disinformation campaigns, propaganda, judicial subversion, cyber-sabotage, financial backing of extremist movements, and the covert engagement of non-state actors, including organized crime and paramilitary groups.

This suite of tactics—deployed under the umbrella of asymmetric balancing—does not require overwhelming material superiority. Rather, it focuses on weakening rival states from within by fomenting instability, eroding public trust in democratic institutions, and fueling political polarization. In Eastern Europe, Russia’s strategy has often revolved around activating Russian-speaking or ethnic Russian minorities as “internal levers” to destabilize democratic consolidation in post-Soviet states. By contrast, in Western democracies such as the United States and EU member states, Russia has gravitated toward supporting far-right populist parties and figures, many of whom espouse anti-EU, anti-NATO, or pro-Kremlin narratives.

In this way, populism becomes a conduit, not only for domestic political discontent, but for external manipulation. Russia’s “war on democracy,” therefore, does not solely involve tanks and troops, but is waged through the subtle distortion of democratic discourse and the strategic exacerbation of democratic weaknesses. Professor Person referred to this terrain as a "populist playground" in which Moscow identifies and exploits social fragmentation for geopolitical gain.

Bringing his analysis into the present, Professor Person cited the United States as a compelling case study. He pointed to recent congressional debates over Ukraine aid, noting how populist rhetoric—particularly from the American right—has contributed to waning bipartisan support for Ukraine’s defense. This trend, he argued, exemplifies the success of Russian strategy in polarizing democratic consensus around foreign policy, thereby obstructing unified responses to Russian aggression. The juxtaposition of halting aid to Ukraine while advancing a domestic tax policy that massively increases US debt, he suggested, reveals the disruptive power of populist narratives in warping strategic priorities.

Throughout his presentation, Professor Person emphasized that Russia’s strategic targeting of democracies is not merely tactical or opportunistic; it is doctrinal. The erosion of democracy abroad enhances Russia’s comparative power and ideological legitimacy at home, where the Kremlin increasingly casts liberal democracy as corrupt, decadent, and destabilizing. Thus, the internal and external dimensions of Russia’s authoritarian consolidation are intimately linked.

In conclusion, Professor Person’s address urged scholars and policymakers to treat democracy not as a passive or self-sustaining system, but as a fragile and embattled political order—one that adversarial powers like Russia are actively seeking to undermine. The presentation served as both diagnosis and warning: while Russia’s material constraints may prevent direct military parity with the West, its strategic sophistication in exploiting the vulnerabilities of democratic societies poses a significant, enduring threat. The defense of democracy, therefore, demands not only military deterrence but a deeper understanding of how information, institutions, and ideology are weaponized in the global contest for influence.

Conclusion

Panel 7 offered a multidimensional and urgent inquiry into the precarious state of democracy in 2025—one caught, much like Schrödinger’s cat, between life and death. Through the lens of legal theory, ethnographic observation, and international strategic analysis, the panel’s three presentations exposed the fragility, complexity, and contested meanings of democratic life across varied contexts.

Dr. Max Steuer’s contribution revealed how law itself can either reinforce domination or serve as an emancipatory tool, depending on how it intersects with populist narratives. His matrix of “legal populism” invites scholars to rethink the role of legality not as an anchor of liberalism per se, but as a battleground where power is contested, justified, and resisted.

Justin Attard’s ethnography turned our attention to the micro-politics of participation in small island states. By theorizing democracy as “lived experience” rather than formal procedure, Attard challenged dominant institutionalist frameworks. His metaphor of democracy in “superposition” deepened our understanding of how democracy becomes real only through social performance, personal proximity, and political embodiment.

Professor Robert Person’s strategic analysis reminded us that democracy is not only internally threatened—it is also under coordinated assault from abroad. His account of Russia’s asymmetric war on democracy underscored how populism can function as a Trojan horse, exploited by hostile powers to divide and destabilize open societies. In a world of shrinking margins for democratic resilience, his call for strategic and institutional vigilance could not be more timely.

Together, the presentations underscored the panel’s central provocation: democracy today is not merely an object of empirical analysis or normative ideal—it is a site of contestation. Its survival, decline, or renewal hinges on how it is interpreted, enacted, defended, and reimagined. Implicit in the panel’s discussions is a call to action: as democrats, our role is not simply to observe the contents of Schrödinger’s box but to actively shape its outcome. Democracy may be simultaneously alive and dead—but it is never inert.

Note: To experience the panel’s dynamic and thought-provoking Q&A session, we encourage you to watch the full video recording above.