Please cite as:

Arzheimer, Kai. (2024). “Germany’s 2024 EP Elections: The Populist Challenge to the Progressive Coalition.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0071

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON GERMANY

Abstract

The 2024 European parliamentary election in Germany marked a significant shift in the political landscape, with devastating results for the governing coalition of the Social Democrats (SPD), the Greens, and the Liberal Democrats (FDP). Chancellor Scholz’s SPD and the Greens experienced substantial losses, while the opposition Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) saw a modest increase in their vote share. The most notable gains were made by the populist radical-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the newly formed left-wing populist Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), a breakaway from the Left (Die Linke), highlighting a growing demand for populist politics in Germany. The Left itself suffered heavy losses. Despite internal scandals and controversies that contributed to a considerable drop in support in pre-election polls, the AfD leveraged anti-immigration sentiments and economic concerns to gain substantial support. The BSW capitalized on left–authoritarian positions, emphasizing welfare and anti-immigration policies. Both parties also criticized Germany’s support for Ukraine and styled themselves as agents of ‘peace.’ The election results underscored the unpopularity of the ‘progressive coalition’ in Germany and reflected the impact of high inflation, energy security concerns and contentious climate policies on voter behaviour. Voter turnout was the highest since 1979, indicating heightened political engagement. Like in previous elections, populist parties were much more successful in the post-communist eastern states. While its impact on the European level is limited, the election sent shock waves through Germany, suggesting a shift in future policy directions, particularly concerning the green transformation and relations with Russia.

Keywords: Alternative for Germany (AfD); Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW); Germany; Russia; Ukraine; east–west differences

By Kai Arzheimer* (Institute for Political Science, University of Mainz)

Introduction and background

The result of the 2024 European parliamentary election in Germany was devastating for the governing three-party coalition of the Social Democrats (SPD), the Greens, and the Liberal Democrats (FDP). Chancellor Scholz’s SPD lost 2 percentage points compared to the 2019 EP election, polling just 13.9%, the worst result for the party in any national election since the Second World War. The Greens, which had done exceedingly well in the 2019 ‘green wave’, lost nearly half their votes and fell back to 11.9%. The Liberals lost only 0.2 percentage points, but their result of 5.2% put them precariously close to the electoral threshold that applies in national elections (although not in European ones).

Conversely, the main opposition Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) polled a combined 30%, a modest 1.1-percentage-point improvement on their 2019 result. While the result ensures they are the strongest party, it is low given both historical standards (they won 44.5% just 20 years ago) and the abysmal approval ratings of the government parties.

The combined vote share of these mainstream parties was just 61%. At least as far as perceptions were concerned, the big winner in these elections was the populist radical-right ‘Alternative for Germany’ (AfD, 15.9%), followed by the new left-wing populist ‘Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance’ (BSW, 6.2%). An additional 17% of the vote went to smaller parties, including the arguably populist ‘Left’ (2.7%), the arguably right-wing populist ‘Free Voters’ (FW, 2.7%), and ‘The Party’ (1.9%), a satirical outfit.

These results were almost perfectly in line with pre-election polls. The so-called ‘progressive coalition’ and its policies have been deeply unpopular almost from the get-go (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, n.d.), and the radical-right AfD has been the main beneficiary of this discontent. More specifically, after the initial rally-round-the-flag effect following Russia’s renewed attack on Ukraine in February 2022, the government’s popularity began to decline due to high inflation and worries about (energy) security.

In 2023, things went from bad to worse for the government and have not improved since. The coalition had planned to re-purpose unused special credit lines enacted during the pandemic to fund their programs for a green transformation of Germany’s economy. The intention was to reconcile the Greens’ ambitious plans for climate protection with the SPD’s interest in expanding welfare and the FDP’s insistence on not declaring a ‘budgetary emergency’ for 2024. While such a declaration would have allowed the government to suspend the constitutional ‘debt brake’, abusing the older credit allowances to notionally comply with the deficit rules was a dubious move at best. Following a complaint by the Christian Democrats, Germany’s Constitutional Court declared the federal budget unconstitutional and void, throwing the coalition in disarray just six months before the election (Kinkartz, 2023). With no money left to paper over them, the fundamental conflicts within the coalition were laid bare.

Early in 2023, the Christian Democrats, alongside much of the media, had also launched a campaign against a government flagship policy aimed at reducing Germany’s CO2 emissions by accelerating the phasing out of older oil and natural gas heating systems. Subsequently, all of the opposition parties and much of the media framed this policy as ideological and removed from the lives of ordinary people, making heat pumps a part of the culture wars and forcing the government to water down its proposals.

As previous Christian Democrat-led governments had signed up to the relevant European and international rules and agreements and had enshrined in German law the very climate targets the policy was designed to meet, this was arguably a populist (in a broader sense) move by the main opposition, one that was happily supported by smaller opposition parties and even by some FDP MPs. Both mainstream and populist opposition parties also sided with large-scale farmers’ protests against some cuts to agrarian subsidies that eventually forced another government U-turn (Arzheimer, 2024).

Finally, Germany accepted more than a million Ukrainian refugees after Russia’s 2022 invasion. While this caused few large-scale problems, an ongoing and very public conflict over funding between the federal government, the state governments and the municipalities, as well as the Christian Democrats’ constant push for harsher rules and stricter enforcement, helped to bring the issue of immigration back onto the agenda in 2023, after its salience had been low for several years (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen n.d.). The Israel–Hamas war played only a minor role in the campaign, but a knife attack by an Afghan man on an anti-Islam activist that left a police officer dead just days before the election triggered a fresh debate about immigration, Islamism and the longstanding policy against deportations to Afghanistan (Deutsche Welle, 2024c).

Against this background, the result of the European elections was hardly surprising. Nonetheless, it sent shock waves through the German polity that still reverberate.

The supply side: populist parties in the ascendancy

Alternative for Germany

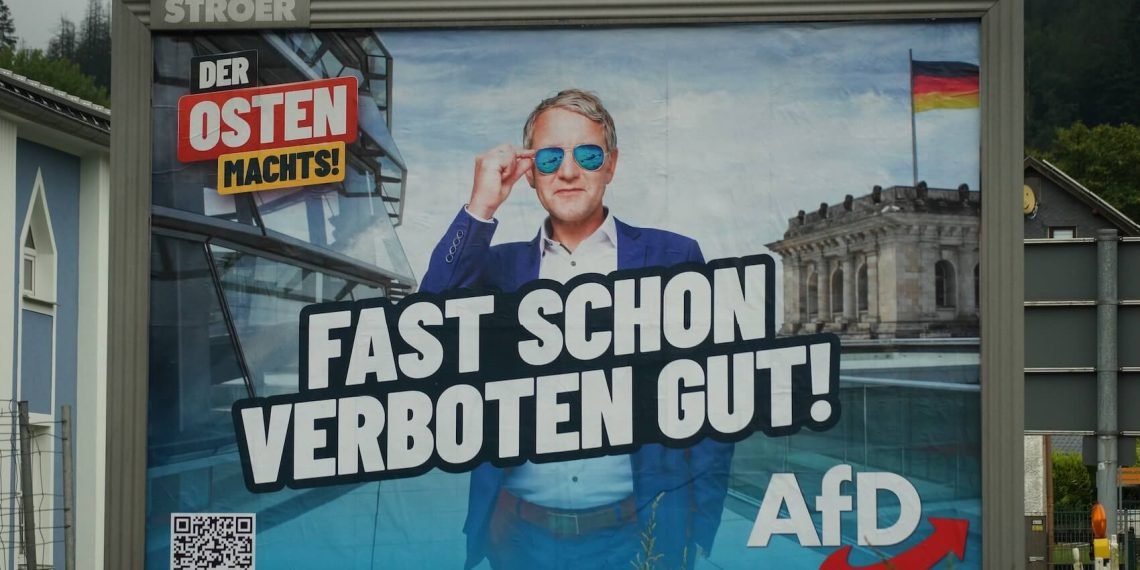

The AfD was founded in 2013 as a right-of-centre, soft-Eurosceptic outfit that presented an ‘alternative’ to the bailout policies that followed the 2010–2011 Eurozone crisis (Arzheimer 2015). It quickly transformed into a characteristic radical-right populist party that attracted the prototypical electorate (Arzheimer & Berning, 2019). While many radical-right parties are striving to soften their public image, the most radical faction has dominated the AfD since 2017 (Pytlas & Biehler, 2023), and the AfD embraces openly extremist actors both within and outside the party (Arzheimer, 2019). As a consequence, the party as a whole is under surveillance by the domestic intelligence agency, and its youth wing, as well as several state branches, have already been classified as right-wing extremist. Like many other far-right parties in Europe, the AfD also has a longstanding association with Russia and has repeatedly voiced sympathy for Putin and his regime. Although the party toned down its statements immediately after the February 2022 invasion, it has since highlighted the economic consequences of the war and the sanctions for Germany and re-invented itself as a party of ‘peace’ (Arzheimer, 2023), even adopting the classic dove symbol in some of its publicity materials.

In the run-up to the 2024 European elections, the party floated the idea of including a call for the dissolution of the European Union in its manifesto, dropping this idea from the final version after a public backlash. However, the selection of candidates was strongly influenced by the most radical elements within the party. The top spot of the list went to Maximilian Krah, a sitting MEP with well-documented connections to German right-wing extremists, Russia and particularly China. Krah’s membership in the Identity and Democracy (ID) group had previously been suspended over allegations of fraud (Dahm, 2023). Petr Bystron, the second on the list, was a sitting MP in Germany’s Bundestag, known both for his extreme views, his fondness of conspiracy myths, and his support for Putin’s Russia. Asked why he would give up his seat in the Bundestag to become an MEP, he said he needed to get to ‘the source of the poison’ (Fiedler, 2023).

In January 2024, the AfD’s campaign got in trouble even before its official start. Investigative journalists reported on a meeting between representatives of the AfD, members of the extremist ‘Identitarian movement’, and potential donors. At the meeting, the participants had discussed plans for a ‘remigration’ – a euphemism for the expulsion of millions of immigrant-origin Germans. This story triggered a large-scale countermobilization, with hundreds of thousands of Germans taking to the streets to protest the AfD (Deutsche Welle, 2024a). These events contributed to a relative decline of AfD support in the polls, which had risen to an unprecedented 22% in December 2023 but dropped to around 17% over the next six weeks or so. It also negatively affected the relationship between the AfD and Marine Le Pen, who dominates the ID group in the European Parliament.

But his was just the beginning of the campaign’s woes. Two months before the election, a Czech newspaper published audio files that strongly suggested that Bystron had received at least 20,000 euros from the Russian propaganda portal ‘Voice of Europe’. As Bystron was a German MP at the time and vote buying is illegal in Germany, he quickly became the object of a full criminal investigation, which is still ongoing. Just a couple of days later, Krah’s parliamentary offices were searched by the police, and one of his aides was arrested as an alleged Chinese spy. While Krah himself has not been charged so far, a preliminary probe into allegations that he sold his vote to China and Russia is still underway (Deutsche Welle, 2024b).

Things came to a head in mid-May when Krah played down the atrocities committed by the Waffen SS in countries occupied by Nazi Germany in an interview with an Italian journalist. In response, the whole AfD delegation in the EP was excluded from the ID group (Reuters, 2024). Krah resigned his seat on the AfD’s national executive and was formally barred from speaking on the stump by the leadership, leading to the paradoxical situation that the campaign rolled on without the two top candidates.

As much of the AfD’s activities are social media-centric anyway, it probably did not matter too much. The AfD continued to push their core issues – first and foremost immigration, but also the economic impact of the war on Germany, climate denialism and hard Euroscepticism – without too much regard for their invisible candidates.

The Left and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance

The Left party is the product of a merger between the (primarily eastern) PDS, itself the successor of the GDR’s former state party, and the WASG, a mostly western group that broke away from the SPD over welfare reforms enacted in the early 2000s (Hough, Koß & Olsen, 2007). It is considered far left and populist (Rooduijn et al., 2023), although many in the party take a rather pragmatic approach to politics, especially at the local and regional levels.

Sahra Wagenknecht was arguably the party’s most prominent, controversial and charismatic politician. She started out as an orthodox communist in the early 1990s, a position that left her isolated within a decidedly post-communist party even after she changed her views. She gladly embraced the role of the outsider. As a gifted and very telegenic public speaker, she has been one of the most frequently invited guests on political talk shows for decades, although she stands for minority positions within a minor party.

During the so-called immigration crisis of 2015–2016, Wagenknecht became a (moderate) immigration sceptic. In 2018, she helped launch a leftist network that brought together tens of thousands of supporters but collapsed when she abandoned it the following year instead of turning it into a personal party, as many had expected. Wagenknecht was also critical of the anti-COVID measures and began cultivating a sizeable audience on social media during the pandemic (MDR, 2024).

In 2021, Wagenknecht published a book that was widely seen as the manifesto of an upcoming political project. In it, she accused her party of pandering to a ‘lifestyle left’ while ignoring the concerns of true working-class voters: welfare and immigration.

The Left’s reaction to Russia’s attack then provided the final straw. The 2011 basic program stresses the party’s links to the peace movement, highlights its ‘internationalist’ credentials and calls for the dissolution of NATO and a ‘common security architecture’ that would include Russia. However, the sheer scale of human suffering in Ukraine has led many in the Left to reconsider these positions. The Left’s manifesto for the European elections reflects this ambiguity. On the one hand, the document is highly critical of the US and NATO and even claims that the eastern enlargement of NATO has ‘contributed to the crisis’ (Die Linke n.d., 65). On the other, it highlights Ukraine’s right to self-defence, condemns the attack as a war crime, and demands that Russia withdraw its troops from Ukrainian territory (without specifying whether that includes Crimea). Wagenknecht, however, took a more clearly pro-Russian stance. She routinely claims that the US and the collective West are blocking a peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine for reasons of their own.

In September 2023, Wagenknecht and her supporters in the Left’s parliamentary registered the ‘Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance — Reason and Justice’ (BSW), which legally became a political party on 8 January 2024. Ten of the Left’s 38 MPs in the Bundestag eventually joined the new group. Amongst state-level MPs and the rank-and-file, the rate of defections was much lower.

This new party created much interest amongst political observers even before it was formally founded because it was assumed that it would cater to the so-far neglected demand for left–authoritarian (i.e., pro-welfare but anti-immigrant) politics in Germany (Wagner, Wurthmann, & Thomeczek, 2023). The EP election manifesto published in April 2024 (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, 2024) offers precisely that, dressed up in a populist fashion. The preamble blames politicians and EU elites for broken promises and ignoring the problems of ordinary citizens. The BSW wants to shrink the bureaucracy and, more importantly, the scope of the European Union by shifting back competencies to the member states.

At the same time and somewhat contradictory, they want the EU to enact higher minimum wages, higher corporate tax rates, stricter rules against money laundering, and limits on financial transactions. The BSW also demands new policies that would allegedly strengthen Europe’s industrial base through a ‘reasonable’ approach to climate protection and securing access to cheap energy and raw materials. This policy is framed as a precondition for expanding welfare. The BSW also rejects future enlargements and wants to curb not just illegal migration but also the recruitment of qualified workers from outside the EU. Instead, the party wants to reduce the ‘push factors’ for immigration by creating more equitable conditions globally. While the rejection of Islam is more muted than in the AfD’s statements, and while the AfD in turn keeps their most radical demands out of their manifesto, this is quite similar to the policies that the AfD offers.

However, the highest degree of overlap with the AfD can be seen in the BSW’s approach to Russia’s war on Ukraine. The sanctions, which are mentioned 14 times in a manifesto of 20 pages, are painted as harmful for Germany while having no effect on Russia itself. For the BSW, the attack on Ukraine is a ‘proxy war’ between the US and Russia (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, 2024: 14) that was ‘started on a military level by Russia’ but ‘could have been prevented and stopped by the West’ (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, 2024: 17). The only (alleged) violations of international law that the manifesto addresses are the Western interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria (Ibid.). The BSW even adopts an idea that the AfD previously launched in parliament (AfD Fraktion im Bundestag, 2023: 3) – making support for Ukraine conditional on Kyiv’s willingness to enter negotiations with Russia – albeit with a twist. It would incentivize Russia by offering to stop all military aid for Ukraine immediately should Russia agree to negotiate.

Demand for populism in Germany

Taken together, the AfD (15.9%), Left (2.7%), and BSW (6.2%) achieved a significant (nearly 25%) share of the vote. Moreover, at 64.8%, turnout was the highest since the EP’s first direct election in 1979, which suggests a high degree of interest and political involvement. Put differently, there is considerable demand for populist politics in Germany, even if the level is still lower than in France or Italy.

In line with second-order-election theory (Reif and Schmitt 1980), domestic actors and attitudes (the unpopularity of the federal government in particular) dominated the campaign. In a post-election poll (see ZDF Heute, 2024), just 10% of the AfD’s voters, 38% of the BSW’s voters, but a massive 85% of the Left’s remaining voters said that ‘Europe’ was more important for their decision than ‘Germany’. This poll result suggests that AfD voters are (even) more inward-looking and fundamentally Eurosceptic than the BSW’s. The average across all parties was 47%.

However, the issues at stake (immigration, Russia’s war against Ukraine, social and economic transformations) are international by nature and were often presented within a European frame of reference by the parties. Moreover, the AfD’s ouster from the ID group, as well the overtures of the (German) president of the commission towards Giorgia Meloni and her European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group, helped to make this one of the most Europeanized EP elections ever.

Nonetheless, support for all three populist parties showed a striking geographical pattern that is very specific to German politics: they are much more successful in the eastern states (i.e., the territory of the former German Democratic Republic). Outside some university towns and the Berlin/Potsdam region, the AfD became the strongest party in all eastern districts and states, with state-wide results varying between 27.5% in Brandenburg and 31.8% in Saxony. In their heartlands in rural Saxony, they won up to 40% of the vote. Conversely, their best results in the western states were 14.7% in Baden-Württemberg and 15.7% in Saarland. There is no western district where they won more than 21%.

These lopsided results are hardly surprising: the multi-faceted legacy of the GDR, the shock and aftermath of the transformation in the 1990s and specific patterns of outmigration have led to a situation where individual levels of populism, nativism and place resentment — the feeling that one’s locale does not get the recognition and resources it deserves — are substantively higher in the eastern states than in the west even decades after unification (Arzheimer and Bernemann 2024). It is, however, important to note that AfD has made considerable inroads in the west of Germany, particularly in regions and even neighbourhoods that could be described as ‘left behind.’

The AfD also drew more support from men (19%) than women (12%), a gender gap that has been stable since 2014, whereas gender differences for the Left and BSW were within the margin of error. For a decade, the AfD was a party of middle-aged voters that struggled to mobilize the very young and the elderly. The latter is still true, but for the first time, AfD support amongst the under-30s is now (just) above average. The Left remains somewhat more popular (6%) in this group than with older voters, while BSW support hardly varies with age.

In socio-structural terms, workers (25%) and voters with medium levels of education (23%) had the highest propensity to vote for the AfD. For the Left and the BSW, there are no clear patterns, but one must bear in mind that in national polls, relatively few of their voters are sampled. Exit polls also suggest that 29% of the BSW’s voters had previously voted for the SPD and another 24% for the Left, while less than 10% were former AfD voters (Palzer, 2024). However, such transition analyses are fraught with methodological problems.

Across all respondents, the AfD remains deeply unpopular, with an average rating of –2.9 on a scale running from –5 to +5. The average values for the Left and BSW are –1.7 and –1.2, respectively. For comparison, the Greens, which have a smaller voter base than the AfD and are the least popular government party, receive a rating of –0.9. This suggests a considerable level of polarization between populist (and particularly radical-right) voters on the one hand and the voters of non-populist parties on the other.

Discussion and perspectives

Both the AfD and the BSW are nationalist parties, and the BSW, in particular, saw the EP election chiefly as an opportunity to gain media attention and access to public funds in preparation for the upcoming state elections. The AfD is still not welcome in the renamed ID (now Patriots for Europe, PfE) group and was forced to team up with a motley crew of fringe MEPs to reach the requisite number for forming a ‘Europe of Sovereign Nations’ group that gives them access to proper funding. BSW has not managed even that, and their MEPs are now sitting as Non-attached (NA). Nonetheless, both the AfD and the BSW will likely vote against any policies related to the green transformation or support for Ukraine and will push for ‘negotiations’ with – and closer economic ties to – Russia.

At least in the short term, however, their most significant impact will be on German politics. If they end up as the strongest or second-strongest party in one or more of the eastern states that go to the polls in autumn, that will have dramatic consequences not just for the Länder in question but for Germany’s system of decentralized and consensual policymaking, which could leave the country in uncharted waters.

(*) Kai Arzheimer is Professor of German Politics and Political Sociology at the University of Mainz. He works in the field of political behaviour, broadly defined and is particularly interested in far-right parties and their voters.

References

AfD Fraktion im Bundestag (2023). ‘BT Drucksache 20/5551’. Der Deutsche Bundestag. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/055/2005551.pdf

Arzheimer, Kai (2015). ‘The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?’ West European Politics 38: 535–56, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230

——— (2019). ‘Don’t Mention the War! How Populist Right-Wing Radicalism Became (Almost) Normal in Germany’. Journal of Common Market Studies 57 (S1): 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12920

——— (2023). ‘To Russia with Love? German Populist Actors’ Positions Vis-a-Vis the Kremlin’. In The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe, edited by Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina, 156–67. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0020

——— (2024). ‘The Far-Right Is Piggybacking on the German Farmers’. Euobserver, 11 January, https://euobserver.com/eu-political/arc8e852f9

Arzheimer, Kai and Theresa Bernemann (2024). ‘“Place” Does Matter for Populist Radical Right Sentiment, but How? Evidence from Germany’. European Political Science Review 16 (2): 167–86. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000279

Arzheimer, Kai and Carl Berning (2019). ‘How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017’. Electoral Studies 60: online first. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (2024). ‘Programm Für Die Europwahl 2024’. https://bsw-vg.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/BSW_Europawahlprogramm_2024.pdf

Dahm, Julia (2023). ‘German Far-Right Led into European Elections by Anti-EU Hardliner’. Euractiv, 31 July 2023. https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/german-far-right-led-into-european-elections-by-anti-eu-hardliner/

Deutsche Welle (2024a, 3 February). ‘Germany: Tens of Thousands in Berlin Protest Far Right’. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-tens-of-thousands-in-berlin-protest-far-right/a-68164252

——— (2024b, 16 May). ‘Germany: Money-Laundering Probe into Far-Right AfD Lawmaker’. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-money-laundering-probe-into-far-right-afd-lawmaker/a-69094119

——— (2024c, 4 June). ‘Mannheim Knife Attack: Authorities Suspect Islamist Motive’. https://www.dw.com/en/mannheim-knife-attack-authorities-suspect-islamist-motive/a-69259747

Die Linke (n.d.) ‘Zeit Für Gerechtigkeit. Zeit Für Haltung. Zeit Für Frieden’. Accessed 21 June 2024. https://www.die-linke.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Europawahlprogramm.pdf

Fiedler, Maria (2023). ‘Extrem, Rechts Und Bald in Brüssel: Wen Die AfD Ins Europaparlament Schicken Will’. Tagesspiegel, 29 July, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/extrem-rechts-und-bald-in-brussel-wen-die-afd-ins-europaparlament-schicken-will-10233988.html

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen (n.d.) ‘Politik II: Langzeitentwicklung Wichtiger Trends Aus Dem Politbarometer Zu Politischen Themen’. Accessed 2 July 2024. https://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Umfragen/Politbarometer/Langzeitentwicklung_-_Themen_im_Ueberblick/Politik_II/

Hough, Dan, Michael Koß, and Jonathan Olsen (2007). The Left Party in Contemporary German Politics. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kinkartz, Sabine (2023). ‘What Is Germany’s Debt Brake?’ Deutsche Welle, 23 November. https://www.dw.com/en/what-is-germanys-debt-brake/a-67587332

MDR (2024, 13 June). Sahra Wagenknecht: from outsider to left-wing icon and party founder, MDR, https://www.mdr.de/nachrichten/deutschland/politik/sahra-wagenknecht-partei-bsw-biografie-100.html

Palzer, Kerstin (2024). ‘Aus dem Stand auf 6,2 Prozent’ Tagesschau, 10 June 2024, https://www.tagesschau.de/europawahl/bsw-linkspartei-100.html

Pytlas, Bartek, and Jan Biehler (2023). ‘The AfD Within the AfD: Radical Right Intra-Party Competition and Ideational Change’. Government and Opposition, online first. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2023.13

Reif, Karlheinz, and Hermann Schmitt (1980). ‘Nine National Second-Order Elections: A Systematic Framework for the Analysis of European Elections Results’. European Journal of Political Research 8: 3–44.

Reuters (2024, 23 May). ‘European Parliament’s Far-Right Group Expels Germany’s AfD After SS Remark’. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/far-right-european-parliament-group-expels-germanys-afd-after-ss-remark-2024-05-23/

Rooduijn, Matthijs, et. al. (2023). ‘The PopuList 3.0’. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2EWKQ

Wagner, Sarah, L. Constantin Wurthmann, and Jan Philipp Thomeczek (2023). ‘Bridging Left and Right? How Sahra Wagenknecht Could Change the German Party Landscape’. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 64: 621–36.

ZDF Heute (2024, 10 June). ‘Europawahl 2024’. https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/

thema/europawahl-142.html