In an exclusive interview with ECPS, Professor Juan Bautista Lucca of the National University of Rosario (UNR) analyzes Argentina’s shifting political landscape under President Javier Milei. He argues that Milei’s project represents “a radicalized hybrid—ultra-neoliberal in economics but ultra-populist in rhetoric.” For Professor Lucca, Milei has transformed neoliberalism into a moral crusade, “sacralizing the market” while turning politics into “a permanent apocalyptic theater.” He views Milei’s alliance with Donald Trump as part of a broader “geopolitics of Trumpism in the Global South,” where sovereignty is redefined through ideological, not strategic, ties. Following Milei’s sweeping midterm victory—with La Libertad Avanza winning 41% of the vote—Professor Lucca warns that Argentina stands in a Gramscian “interregnum,” facing both consolidation and disillusionment.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In an in-depth interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Juan Bautista Lucca, a leading political scientist at the National University of Rosario (UNR) and Independent Researcher at CONICET, offers a comprehensive analysis of the Javier Milei phenomenon, situating it within Argentina’s longer populist tradition while revealing its radical departures from the past.

Reflecting on Milei’s sweeping midterm victory, Professor Lucca rejects the idea that the results represent a referendum on economic policy. Rather, he sees them as “an expression of the president’s capacity to maintain a narrative of radical rupture and moral regeneration.” For Professor Lucca, Milei’s strength lies not in delivering material results but in sustaining an affective narrative of moral renewal, one that continues to mobilize polarized sectors of society while leaving centrist voters disengaged. “People in the center,” he observes, “are not very motivated to vote… participation was one of the lowest in the last 40 years of democracy in Argentina.”

Professor Lucca identifies a deeper “normalization of populist discourse” in Argentina’s political mainstream, in which neoliberal orthodoxy is now “celebrated as an act of moral courage.” Unlike past neoliberal leaders such as Carlos Menem or Mauricio Macri, who concealed their economic programs, Milei “doesn’t want to hide this economic agenda; he even sacralizes it.” This, Professor Lucca argues, represents the sophistication of neoliberal populism, where austerity and moral regeneration are fused into a coherent political language.

Asked whether Milei’s libertarian project fits within existing typologies, Professor Lucca insists it marks a qualitative rupture: “He is ultra-neoliberal in economics but ultra-populist in rhetoric.” Milei’s “libertarian populism,” he explains, blends market maximalism and anti-establishment radicalism with “messianic performativity.” His leadership, characterized by a “rock-star persona and apocalyptic imagery,” transforms politics into what Professor Lucca calls “a permanent apocalyptic theater,” where representation depends less on programs than on emotional intensity.

From a geopolitical perspective, Professor Lucca sees Milei’s alliance with Donald Trump and symbolic alignment with Israel as evidence of a “geopolitics of Trumpism in the Global South”—a transnational ideological coordination that redefines sovereignty through shared cultural codes rather than strategic alliances. In this worldview, “external financial dependence is reframed as liberation,” an inversion of Argentina’s traditional narratives of autonomy and self-determination.

Looking ahead, Professor Lucca warns that Argentina stands “in an interregnum—what Gramsci called the time when monsters appear.” Whether Milei’s Leviathan endures or gives rise to “a Behemoth from populist Peronism” remains uncertain. Yet, he notes, the greatest danger lies in a growing “third Argentina”—a disenchanted electorate that “simply doesn’t want to participate in politics.”

Milei’s midterm triumph underscores the urgency of Professor Lucca’s diagnosis. With La Libertad Avanza capturing nearly 41% of the vote, securing 13 of 24 Senate seats and 64 of 127 lower-house seats, Argentina’s president has consolidated his grip on power. The landslide—hailed by supporters as a rejection of Peronism and condemned by critics for deepening inequality—marks a pivotal moment in Argentina’s democratic experiment: one where chainsaw economics meets populist spectacle, reshaping both the country’s political grammar and its social contract.

Here is the edited transcript of our interview with Professor Juan Bautista Lucca, slightly revised for clarity and flow.

Milei’s Victory Is Not an Economic Referendum, but a Moral One

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: In light of Javier Milei’s surprising midterm victory, how do you interpret this result as a referendum on two years of libertarian governance amid economic contraction, corruption scandals, and low turnout? What does it reveal about the resilience and transformation of right-wing populism in Argentina?

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: It’s a complex question, so I’ll try to answer as much as I can. First of all, I have to say that it’s not surprising—the number of people who support Milei. But even if I say that, I could also say that this is a kind of referendum for them, or a referendum on concrete economic results. I would say that the result of the last election is more an expression of the president’s capacity to maintain a narrative of radical rupture and moral regeneration.

Even if in the 2023 election he didn’t campaign against Kirchnerism as much, he opposed the idea of la casta. But now, he incorporates the idea of anti-Kirchnerism, and it was very effective in nationalizing the election—turning what was essentially a provincial or local contest into a national one. He was able to make it a national debate. So, it’s not a referendum on economic policy.

I also have to add that the low electoral turnout, in a way, shows that those who went to vote are mostly the highly polarized ones. People in the center, who don’t agree with either side of Argentina’s antinomic populist politics—with Peronism and Kirchnerism on one side, and La Libertad Avanza or Mileism on the other—are not very motivated to vote. People in the center of the ideological spectrum, or those distant from this cleavage, tend to stay home. That’s why participation was so low—one of the lowest in the last 40 years of democracy in Argentina.

Argentina Is Witnessing the Normalization of Neoliberal Populism

To what extent does this electoral outcome signal the normalization of populist discourse within Argentina’s political mainstream—especially when neoliberal prescriptions are wrapped in anti-elitist and moralizing rhetoric?

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: We are facing an unsettling but truly effective normalization. This normalization started more or less three years ago, when the mainstream right accepted that Milei is not just an outsider, and their debate, discourse, and programmatic perspective—or their ideological propositions on policies—were no longer as radicalized as they had been maybe ten years ago. So, the normalization of Milei’s discourse really began three or four years ago.

During the pandemic period, this discursive operation represented the sophistication of neoliberal populism as we knew it in Argentina with Menem or Macri in the past, because they no longer need to hide their economic program. In the past, we could see that Macri and Menem tried to conceal their programmatic preferences. They didn’t openly express the idea that we were in the midst of a new or renewed Washington Consensus. But now, Milei doesn’t want to hide this economic program; they even celebrate it as an act of moral courage, perhaps.

This is important for Argentina’s political imagination, where Washington Consensus prescriptions were always very unpopular but are now gaining more and more popular legitimacy. That’s why we are witnessing the normalization of this radical discourse. We could see it in the last two elections, this year and in 2023, when the idea of controlling debt and the state deficit was celebrated by all participants in the election—even the Peronist candidate, Massa.

Right now, other candidates on the Peronist side have decided to accept the idea of controlling the deficit and reducing not only social policies but also other kinds of spending—the amount of money wasted on unproductive policies, especially at the provincial and subnational levels. Governors have decided to accept Milei’s neoliberal restrictions on spending for policies, infrastructure, and other kinds of initiatives. And when they accept these ideas and policies, they are normalizing the programmatic perspective of our president.

Milei and Trump Share a Cultural, Not Just Political, Alliance

Given the US bailout and Donald Trump’s open political intervention, how do you evaluate this episode as an instance of transnational populist coordination? Does it point to a new geopolitical articulation of Trumpism in the Global South?

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: It’s a complex question. Of course, there is a strong link between Trump’s administration and Milei’s administration, but I also have to note that it is a strong relationship between both individuals, not merely an administrative connection. This shows that Trump is not supporting Milei as a conventional geopolitical ally, since in Latin America there are other countries that are more powerful or geopolitically significant—perhaps nations in the Caribbean or Brazil. The link between Trump and Milei is more about companionship within a global and established movement that shares certain cultural codes, symbolic enemies, and a specific vision of the world—particularly the defense of Western civilization.

We could see this in Milei’s administration when he chose Israel as the first country to visit as president, breaking a long-standing tradition in Argentine administrations since the return of democracy. Traditionally, the first country an Argentine president visited was Brazil. Milei broke with that, and this reflects not only his stance toward Israel but also his affinity with Trump. This is not a geopolitical expression but rather a relationship rooted in cultural codes and a shared worldview.

This effectively points toward geopolitics of Trumpism in the Global South, where national sovereignties are paradoxically redefined through transnational ideological alliances. In this case, the alliance is supported not only by ideological affinities but also by shared cultural representations of how they enact their policies. For example, the recent government shutdown in the Trump administration is more or less the same as what has been experienced since the beginning of the Milei administration with the shutdown of the budget—used as a political strategy.

If we look not only at the link between Trump and Milei’s administrations but also at the policies they are implementing in both countries, they are largely similar. This convergence shows how they choose to express their alliance not only at the geopolitical level but also in domestic politics.

Milei Redefines Dependence as Liberation and Sovereignty as Submission

How might such external dependencies—both financial and ideological—reshape Argentina’s historical narrative of sovereignty and national autonomy, central tropes within both Peronist and anti-Peronist imaginaries?

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: That’s a fantastic question, because it can be answered through the lens of the Milei administration, which is presenting—or perhaps performing—a radical act of resignification. With Trump’s support and the effort to stabilize the financial system, Milei frames external financial dependence as a form of liberation. It’s a contradiction in terms, but it’s highly effective in gaining support from the electorate. He has also reframed integration into the global neoliberal order as an authentic expression of individual sovereignty. It’s a deeply paradoxical move: he presents liberty where there is dependence and defends sovereignty while effectively handing over the keys to the Trump administration on one of Argentina’s most critical issues—the financial question, debt control, and inflation rates.

Milei Doesn’t Defend the Market—He Sacralizes It

In your studies of ideological structures in Argentine and Latin American politics, you have discussed how right-wing projects often recode neoliberal rationality through affective populist idioms. How does Milei’s “anarcho-capitalism” fit within, or rupture, that ideological tradition?

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: We see both continuities and ruptures in the idea that Milei is an anarcho-capitalist. How can we analyze that in relation to your question? It represents continuity because it effectively reintroduces neoliberal rationality through an affective populist medium. Sometimes we saw this in more moderate forms with Menem and Macri. However, the Argentine right has traditionally expressed anti-populism in its discourse while employing populism in its strategy. For example, Macri opposed the populism of Kirchnerism, yet in his strategy, he created a sharp distinction or cleavage between one side and the other—constructing a Manichean narrative that was entirely populist, even if he never admitted to being one.

If we use Pierre Ostiguy’s framework, for instance, Macri’s administration was led by elites at the top, but at the subnational level—in the provinces—it relied heavily on “low culture,” which Ostiguy defines as populist.

In Milei’s case, however, there is a rupture with this tradition because he takes the operation to an unprecedented extreme. He radicalizes it. He doesn’t merely defend the market; he sacralizes it. He doesn’t simply criticize the state, as Macri or Menem did; he demonizes it. He presents a more apocalyptic vision. His anarcho-capitalism functions less as a coherent economic doctrine and more as a political mythology. That’s why he promises redemption through the destruction of the existing order. He often says that we need to “burn Rome once again”—in this case, Argentina.

The idea is to push this populist narrative to its limits, portraying society as living in hell, with him as the only one capable of leading it to paradise. It is framed in a far more apocalyptic and radicalized way than in previous expressions of the right in Argentina, such as those of Menem and Macri.

Milei’s Libertarian Populism Blends Market Maximalism with Messianic Performativity

Can we analytically conceive Milei’s project as a form of neoliberal populism, or does its radical libertarianism, combined with moral anti-statism, constitute a novel ideological hybrid that transcends earlier typologies such as the “New Right” of Menem or Macri?

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: It is, once again, a very complex question, and I think we need more time—or at least we need to see the full picture of Milei’s administration—to provide a more conceptually precise answer. But if I had to give a quick one, I would say that while the neoliberal populism of Menem and Macri sought a certain pragmatic balance between market logic and popular demands, in Milei’s case, he radicalizes both poles simultaneously. He is ultra-neoliberal in economics but ultra-populist in rhetoric.

His libertarianism is not merely technical; he moralizes it. As I mentioned in the previous question, he presents it as a religious issue. This kind of libertarian populism—if I may use that term—is an ideological configuration that combines market maximalism and anti-establishment maximalism with messianic performativity.

It’s like old wine in a new bottle served in a new kind of cup: something broadly familiar but with a completely different flavor. It is presented as a revelation, almost mythological—something that doesn’t fit easily within earlier categories like the New Right or neoliberal populism. It is genuinely new in the sense that Milei adds this messianic, performative, almost religious dimension to the mix of market ideology and anti-establishment maximalism in his politics.

Milei Reverses the Latin American Populist Tradition

Considering your engagement with Torcuato di Tella’s work on national-popular coalitions and Bonapartism, how might Milei’s project be situated within—or against—that lineage of Latin American populisms that sought to reconcile mass incorporation with elite hegemony?

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: The comparison with di Tella is very productive, because di Tella knew the Peronist strategies intimately and how they evolved over time. He was present at every table where Peronism sought to articulate its power, at least during the last democratic period.

The classical national-popular populism that di Tella analyzed aimed to build coalitions under charismatic leadership that mediated between elites and the masses. It was a kind of reinterpretation of Maurice A. Finocchiaro’s idea of leadership. Di Tella saw this leadership in a positive light, while Finocchiaro viewed it as something negative for democracy.

In Milei’s case, however, he inverts this logic. He builds an anti-distributive coalition under charismatic leadership. He takes di Tella’s framework and completely reverses it—turning it upside down, so to speak. Milei not only inverts the logic that di Tella described but also preserves the Bonapartist structure characterized by concentrated power and a direct, plebiscitary relationship with the people. In this context, he relies heavily on new technologies like social media, which played a far greater role in the 2023 election than in this one.

This is partly because we are now in a midterm election where President Milei himself was not a candidate, so each candidate had to express their allegiance to Milei’s narrative through their own social media channels. As a result, the power and potential of social media became fragmented across multiple actors.

To conclude, Milei’s rise represents both an appropriation and a distortion of the traditional Latin American populist model that di Tella described—pushed toward radically opposite ends, the ultimate outcome and final shape of which remain uncertain.

Milei Turns Politics into a Permanent Apocalyptic Theater

The performative excess of Milei’s leadership—his rock-star persona and apocalyptic imagery—has become central to his political grammar. From your theoretical perspective, how does this form of charismatic performativity reconfigure the populist relation between representation, spectacle, and crisis?

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: Milei is an outsider from the political elites in Argentina, but he’s also someone who came from the media, and he realized very quickly that in the era of spectacularized politics, representation is not based on programs but rather on affective intensity. The performativity that Milei embodies is not ornamental—it is constitutive of Milei and Mileism itself.

The insults, the rock aesthetic, the apocalyptic references—even the hair, in a kind of Boris Johnson or The Cure singer (Robert James Smith) way—are not simply part of a communication strategy. They are the cornerstone of his political force. His charismatic performativity produces what we could call a politics of permanent event, and he uses social networks to sustain it every day. He sends more tweets and posts than the time he spends sleeping.

He reconfigures populism away from institutional constraints into a logic of pure messianic events. It is a populism—a permanent apocalyptic theater. And Milei, more than anyone, understood that very quickly and very clearly. That’s why it was so effective during the election period.

Milei’s Leviathan May Soon Face a Behemoth from Populist Peronism

And the last question is: Looking ahead, do you foresee Argentina entering a phase of libertarian-populist consolidation, or are we witnessing the incipient exhaustion of a political model whose moral and economic contradictions may soon reinvigorate a re-articulated Peronism or left-populist alternative?

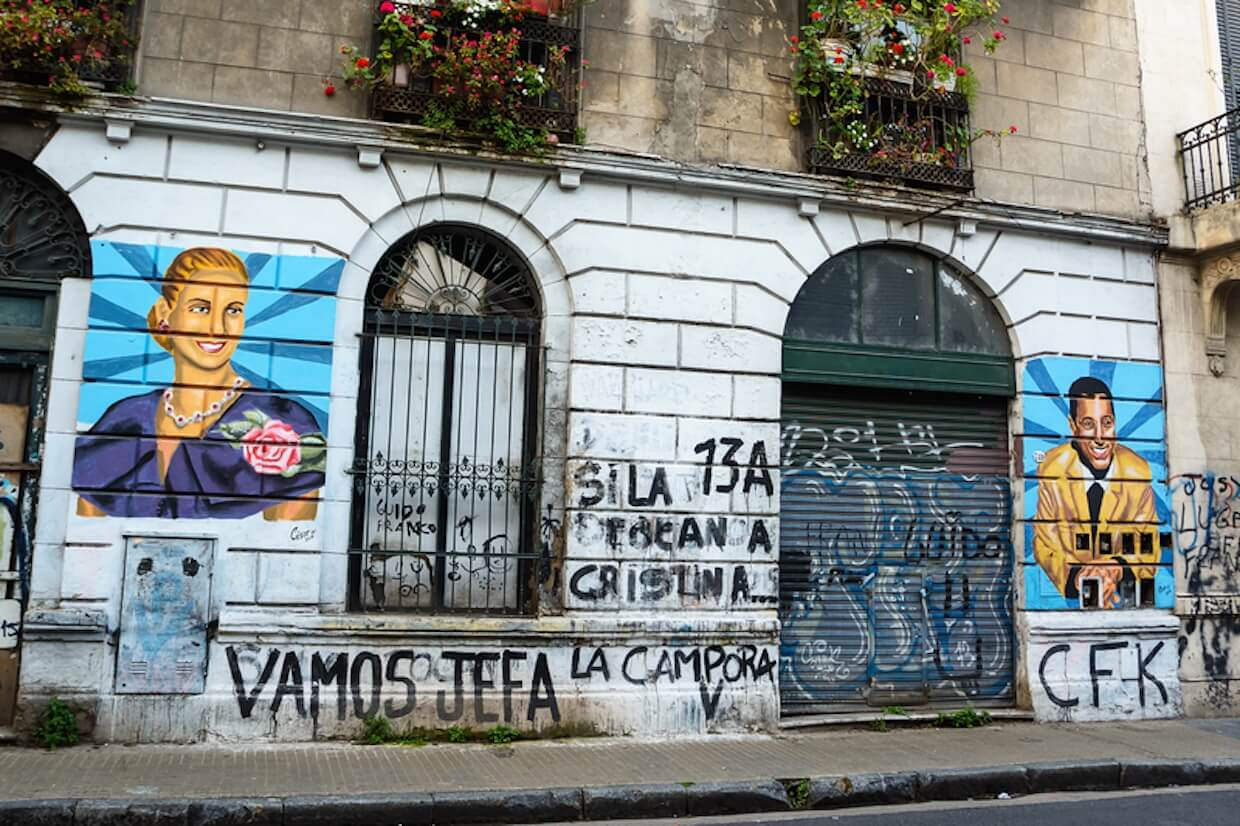

Professor Juan Bautista Lucca: It’s not easy. If I could see the future, I would say that we are in the middle of a transitional period—an interregnum, as Antonio F. Gramsci might say. And, Gramsci said that in these transitional moments, monsters tend to appear, and Milei is one of those monsters. But the question is what will come after—I don’t know. And whether Milei will be the only monster in town, maybe, I don’t know either. I think we are entering a future where this kind of Leviathan that Milei is now creating will be confronted by a Behemoth from populist Peronism. They are trying to reorganize their forces and establish new leaderships in the absence of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

From my perspective, the only critical scenario we could foresee in the near future is if the policies that Milei has presented, expressed, and implemented produce bad results and outcomes. At the moment, there is no antagonistic opposition capable of confronting and defeating Milei. The only one who could defeat Milei is Milei himself. But this is not an unrealistic scenario, because Milei is an outsider. He is not part of la casta, so he must go through a long and complex process of learning—how to debate, how to build consensus, and how to uphold the informal institutions of Argentine political culture. He needs to understand this background and learn to engage with the other elites who have governed Argentina for maybe twenty or more years in every province. The territorial power of governors in Argentina is very strong, so he needs to negotiate and reach consensus with them.

So, I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I don’t anticipate a simple return of traditional Peronism. It’s more likely that we will see the emergence of a new political articulation—perhaps a renewed form of left-wing populism that learns from Milei’s capacity to connect affectively. Because this is key in Argentina right now: polarization is not ideological—it’s affective. People are divided by emotions and feelings that bring them closer to or further from Milei. That’s why, as I said before in your first question, this election expressed a position of fear that is not linked to either pole of this antagonistic populist divide. There is a third Argentina that is not represented in this election. And it is not expressed because these people don’t want to show their hatred or opposition to Milei’s policies—they simply don’t want to participate in politics. This is something completely new in Argentina. Even during the pandemic, when people were angry or opposed to Alberto Fernández’s government and its policies, they still voted for new parties. But now, more than 30% of people don’t want to participate; they don’t want to belong to either pole of Argentina’s polarization. This is a completely new phenomenon that we must interpret and analyze carefully when the time comes.