Professor Luke March, from the University of Edinburgh, underscores that any surprises or intrigues in the upcoming Russian presidential elections are minor curiosities rather than significant events. He argues that these elections will further consolidate Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian rule, possibly securing up to 80% of the vote. According to March, Putin’s underlying message is clear: his dominance remains unassailable in the foreseeable future; any attempt at opposition will be swiftly quashed. March emphasizes his expectation that this pattern will persist without significant deviation.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

Professor Luke March, holding a Personal Chair of Post-Soviet and Comparative Politics at the School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh, emphasizes that any surprises or intrigues in the upcoming Russian presidential elections are more akin to minor curiosities rather than significant events. He argues that this election will serve as another milestone in the consolidation of Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian rule, potentially securing as much as 80% of the vote.

The presidential election in Russia is scheduled to take place from March 15-17, 2024, marking the eighth such election in the country’s history. The winner is set to be inaugurated on May 7, 2024. In an exclusive interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS) prior to the election, Professor March commented, "Should Putin secure 80% or 85% of the vote, it wouldn’t be unexpected, as it effectively leaves no space for opposition. Once again, these elections are poised to reinforce Putin’s status as a central figure and patron of the elite. The message he seeks to convey is one of unchallengeable authority in the foreseeable future; while individuals may attempt to challenge him, they will inevitably face suppression. I foresee no significant deviation from this established pattern."

By delving into the Kremlin’s tactics in manipulating the opposition, both systemic and non-systemic, Professor March draw attention to the marginalization of dissenting voices, the crackdown on protests, and the co-option of certain figures to maintain control over the political landscape. March addressed the complexities surrounding the conceptualization of Putin’s politics, particularly the existence of a coherent ‘Putinism’ and its ideological syncretism. He highlighted Putin’s employment of paradigmatic pluralism to bridge various ideologies, ultimately fostering a sense of cohesion within his regime.

Assessing the role of populism and nationalism within Putin’s regime, both domestically and internationally, Prof. March discussed how Putin strategically employs populist rhetoric and nationalist sentiments to garner support and suppress dissent, particularly in the context of events like the invasion of Ukraine. However, March acknowledged the vulnerabilities within the Russian political system, such as economic challenges, casualties in warfare, and inflation. Despite these pressures, he noted that current measures are aimed at ensuring that no political entity can capitalize on these grievances, highlighting the Kremlin’s success in maintaining control thus far.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Luke March with some edits.

Putin Tends to Employ Populism in External Contexts

How do you see the complexities surrounding the conceptualization of Putin’s politics, particularly regarding the existence of a coherent ‘Putinism’ and its ideological syncretism? Does populism play a role in Putin’s regime, particularly in light of its presence within Russian politics and state media environment? What are the main weaknesses and challenges encountered when attempting to classify Putin as either an elitist or a populist leader?

Luke March: Putin employs a form of paradigmatic pluralism in an effort to bridge various ideologies, aiming to foster a sense of cohesion within his regime. However, there exists a notable dichotomy between Putin himself and the overarching ideology of Putinism, which has evolved into an increasingly monolithic entity. While Putin embodies certain principles, they are subject to interpretation by the media and various politicians. This inherent flexibility allows for creative interpretation within certain boundaries, as long as the fundamental nature of the state is not challenged.

This approach presents challenges, as the regime embraces a diverse range of ideologies, albeit with a growing coherence around right-wing nationalism. Populism also plays a significant role, utilized more prominently by opposition figures and the media rather than by Putin personally. Furthermore, Putin tends to employ populism more frequently in external contexts rather than domestically.

One fundamental challenge lies in grasping the implicit rules governing Russian politics, which have become increasingly elusive and difficult to research. This difficulty stems from the tight control exerted over politics, particularly by the security services, despite the facade of diverse ideologies. Any discussion of these ideologies must acknowledge the reality of mounting state control.

When analyzing how Putin utilizes specific ideologies, it’s crucial to consider his leadership within a controlled state apparatus, backed by increasingly repressive measures. Despite espousing rhetoric that may seem populist, such as emphasizing the importance of the Russian people and their values, Putin simultaneously employs coded language emphasizing loyalty, respect for national interests and unity around state objectives. This duality underscores a reciprocal relationship where the state serves the people, but the people are also expected to serve the state.

The characterization of Putin’s approach as merely elitist falls short of capturing its full complexity. While there is an elitist aspect, it differs from historical models like the Bolshevik period, where the party claimed a leading role. Instead, Putin’s elitism operates more subtly, emphasizing the state as the unifier of both elite and populace, with obedience to the elite representing obedience to the state. These messages, conveyed through both overt and coded means, allow authorities to maneuver and adapt as needed. Populism, when applied to Putin’s regime, fails to fully encapsulate this nuanced dynamic, as it operates in distinct ways within the Russian context.

Putin Allows Others to Depict Him as a Superman

In terms of leadership style, Putin has usually been described as exhibiting a "bad boy" populist persona. How does this persona align with or diverge from traditional populist leadership styles, and what are its implications for understanding his political strategy? Moreover, how does Putin’s leadership fit into charismatic leadership framework, considering his reliance on incumbency advantages, control of mobilization, and aversion to popular spontaneity?

Luke March: It’s a complex element once again. At first glance, Putin shares numerous commonalities with other infamous figures dubbed "bad boys" or disruptive populist leaders such as Trump, Bolsonaro, and others, particularly those on the right-wing spectrum. His persona revolves around a macho, strongman image—someone who can be crude, cracks sexist jokes, and strongly advocates patriarchal politics and superhuman feats. However, this depiction only partially captures Putin’s actions. In the West, we often focus on these facets, sometimes even finding amusement in them, especially in the UK where our view of leadership differs significantly.

Yet, there’s far more complexity at play. Putin frequently exhibits sober, restrained behavior, akin to a military or business leader, adopting a CEO-like demeanor. While he occasionally indulges in the pomp and ceremony associated with a Tsar-like figure, much of the time he presents himself in a business suit, embodying a less emotive, more calculated style, devoid of the outbursts seen in populist leaders. He can slip into the populist role when necessary, but also assumes a more nuanced persona. It’s crucial to recognize his background as a representative of the security services in the Soviet state. Thus, when he employs macho language and threats, there’s a subtext pointing to his underlying authority and the genuine menace behind his words. Although Putin’s character has evolved over the past couple of decades, the increasing severity of his repressive actions is becoming more apparent.

In terms of charisma, he undeniably exudes a certain charismatic authority, largely rooted in his widespread popularity. Much of this popularity stems from his portrayal as someone above the party system, viewed as essential to the discourse surrounding the creation of the Russian State. However, it’s worth noting that much of this narrative isn’t directly promoted by Putin himself, but rather by individuals acting on his behalf, who assert, "We need Putin, and we can’t envision the Russian State without him." Even the head of the Russian Orthodox Church has referred to him as "a miracle of God." This has fostered a sort of mini personality cult around him, despite his tendency to downplay such notions and present himself in a sober, teetotal, and non-drinker persona. He allows others to depict him as a superman, adding further layers of complexity to his image—partially populist, yet encompassing many other facets as well.

The Space for Ideological and Rhetorical Opposition Has Shrunk

In one of your articles, you discuss the impact of Putin’s intervention in Crimea (and of course intervention in Ukraine now) on the domestic political situation in Russia, particularly regarding the marginalization of non-systemic opposition groups. Could you elaborate on how this crisis has affected the dynamics between the Kremlin and both systemic and non-systemic opposition movements in Russia?

Luke March: In a nutshell, it’s contributed to the crushing of the opposition, erasing any coherent dissenting voices. While individuals remain, they lack the organizational structure to pose a significant challenge. Many prominent figures of the non-systemic opposition have either been forced into exile, imprisoned, or, in tragic cases like Navalny’s, silenced permanently. A significant outcome has been the bolstering of Putin’s popularity. This strategy also succeeded in co-opting Russian nationalist sentiments. Putin has strategically portrayed himself as a nationalist leader, emphasizing his role as a guardian of Russian territories and heritage, positioning himself as a historical figure who is making Russia great again.

He made it exceedingly challenging for people to criticize him, fostering a rally-round-the-flag effect that portrays critics as traitors. This tactic has exacerbated tensions internationally, allowing him to label domestic opposition as traitorous or pro-Western fifth column. Simultaneously, there’s been a conservative shift in Russian politics, with Putin aligning more closely with conservative nationalist ideals. This shift has effectively silenced dissent, bolstered by legal restrictions on opposition that intensified after February 2022, particularly regarding criticism of so-called “military operation.” The space for ideological and rhetorical opposition has shrunk alongside legal avenues, buoying Putin’s popularity while increasing repression. Consequently, genuine opposition voices are scarce, evident in the upcoming elections where systemic opposition refrain from critiquing Putin’s regime.

Putin’s Core Strategy Is Top-Down Control Aimed at Maintaining Authority

In your article "Putin: Populist, Anti-populist, or Pseudo-populist?", you argue that Putin’s ideology subverts populism, using populist ideas and rhetoric in service of the authoritarian state. Also, you argue against characterizing Putin as substantively populist. Could you elaborate on why you do not see Putin as a populist leader, particularly in terms of his approach to people-centrism, anti-elitism, and popular sovereignty?

Luke March: On one hand, those elements are present, and Putin can adopt a populist approach when it suits his purposes. On the other hand, while my previous responses touch upon certain aspects, they only scratch the surface of Putin’s comprehensive rhetoric. Ideologies such as statism and conservatism play equally crucial roles. Putin’s aversion to popular mobilization is deeply ingrained, likely stemming from his background as a security service agent in the GDR during the fall of the Berlin Wall. This suspicion extends beyond just the elite to encompass all forms of mass mobilization.

So where does he incorporate elements of populism? They seem rather disconnected. When he focuses on people’s centrism, it doesn’t necessarily align with anti-elitism. When he does emphasize anti-elitism, it’s often rooted in historical references, such as his rhetoric regarding Ukraine, where he highlights how the Bolsheviks drew up Ukraine against the wishes of the Russian people. However, his critique extends beyond internal elites to include Ukrainian and Western elites. Yet, this critique of Western elites doesn’t seem to be tied to a broader vision of popular sovereignty. So, these elements aren’t interwoven in the fundamental way one might expect from a populist leader. He doesn’t consistently advocate for people’s power everywhere. While he may speak vaguely about fighting for the underdog globally and criticize Western elites, it’s more of a horizontal critique against outsiders rather than a vertical critique advocating for the people against the elite.

That’s also evident in his approach to the situation in Ukraine, where he criticizes what he terms the "coup" but doesn’t advocate for empowering the Ukrainian people in response to the power shift. Instead, he calls for Ukrainians to seek protection from the West by aligning with the Russian people. Thus, his use of populism serves more as an anti-Western critique rather than a genuine appeal to populism. While there may be individuals within the Kremlin who employ a more populist rhetoric, Putin’s core strategy revolves around top-down control and centralization, aimed at maintaining authority rather than empowering the people.

You discuss the concept of "official nationality" in Russia, emphasizing its moderate conservatism and promotion of civic nationalism. How does the Kremlin balance the promotion of this ideology with the need to control more extreme forms of nationalism, particularly those that may challenge its authority? Can you elaborate on how the Kremlin strategically employs nationalism to garner support and suppress dissent, and how effective has this approach been in preserving elite power?

Luke March: It’s a delicate balance that they have often shifted between. When examining the rhetoric coming from the Kremlin, particularly figures like Foreign Minister Lavrov and those surrounding Putin, it has typically been characterized as sober, realist, and rooted in state interests, at least until the past decade. However, over time, this balance has become more porous, especially with the onset of the war in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. The Kremlin has increasingly drawn upon a domestic nationalist consensus. About 15 years ago, Putin may have been more inclined towards a pro-European stance, perhaps critical of the US. However, in the last decade, his rhetoric has shifted significantly towards anti-Western sentiment, coupled with critiques of Western liberalism and so-called "woke politics."

To a certain extent, I believe the official stance on nationality has grown increasingly nationalistic, with Putin aligning himself with some domestic nationalists, such as Alexander Dugin, who were previously viewed as extremists. Their ideologies have now permeated into the mainstream, particularly evident within the media landscape and amidst the ongoing conflict. Many commentators on Russian television espouse overtly nationalistic views, including discussions about the potential obliteration of Ukraine as a nation. Comparatively, Putin’s rhetoric appears more measured, often emphasizing the pursuit of peace deals. However, the Kremlin’s allowance for nationalist voices to dominate the political discourse underscores a shift towards framing official nationality as a clash of civilizations between Russia and the West. While it may still retain some semblance of moderation, this stance has undeniably veered towards extremism over time.

Rather Than Crudely Rigging Elections, Kremlin Prefers to Shape Electorate’s Choices in Advance

In one of your articles, you draw parallels between the dystopian depiction of political control in "The Hunger Games" and the situation in Russia, where opposition parties are manipulated to reinforce the Kremlin’s authority. How do these manipulations manifest in the political landscape, and what strategies does the Kremlin employ to maintain control over opposition activities? Furthermore, what factors could undermine Putin’s support in the long term, and how might the opposition capitalize on the systemic vulnerabilities to challenge Putin’s regime?

Luke March: There exists a complex network of control within the party system, often channeled through figures like Sergei Kiriyenko and the Presidential administration, previously led by Vladislav Surkov. Understanding this network is exceptionally challenging, given its informal nature, relying heavily on circumstantial accounts from Russian political scientists and media sources, which are not as transparent as they once were. The significant caveat in addressing this issue is that ultimately, the full extent of this control remains elusive and uncertain.

However, information occasionally seeps out, as was the case a couple of weeks ago when a consortium of Western media released a report called "Kremlin Leaks." This report detailed the informal methods through which the Kremlin channels funds into propaganda, media, and education spheres, as well as its strategies concerning the opposition. Rather than overtly and crudely rigging elections, the Kremlin prefers to shape the electorate’s choices in advance. This is not to suggest that Putin couldn’t win a free and fair election, but such an election would have a vastly different dynamic. To control the narrative, pressure is exerted on political parties to pre-select candidates aligned with the Kremlin’s interests. A notable example is the case of the Communists in the 2018 election, who fielded a businessman named Pavel Grudinin, garnering 11% of the vote. While not particularly impressive, Grudinin began gaining traction as a national-scale political figure and potential future leader of the Communist Party. However, through various subterfuges, including attacks on his business and family disputes, he was eventually ousted from politics. This illustrates one of the ways in which such manipulation occurs.

As I’ve mentioned, there’s been a significant increase in regulation and restrictions on street protests, especially regarding demonstrations concerning the war. This is one aspect. Additionally, the Kremlin’s message, exemplified by the assassination of Navalny, serves to delineate the boundaries of what can be achieved. Consequently, opposition politicians and protestors who persist must display immense bravery and commitment. Many politicians opt for self-censorship or refrain from challenging fundamental issues altogether. For a considerable duration, no opposition figure of substantial influence has dared to criticize Russian foreign policy in a fundamental manner. For instance, during the original annexation of Crimea, the Russian Parliament approved it with a vote of 449 to 1, with the lone dissenting voice being Ilya Ponomarev, who had to flee into exile in Ukraine. This prevailing trend, facilitated through both formal and informal means, underscores the extreme difficulty faced by the opposition in expressing dissent.

Russia Has Positioned Itself as a ‘Muslim Power’

Referring to one of your surveys, how do Russian policy-making and academic elites conceptualize the idea of ‘radicalization’ within the context of Islam, and what are the key factors they identify as contributing to this phenomenon? How does Russia’s approach to combating radicalization domestically influence its foreign policy towards the Muslim world?

Luke March: The concept of radicalization finds more resonance in Western and UK circles than in Russia, although it has been referenced to some extent. However, over time, the notion of radicalization has often been overshadowed by that of extremism, which has been wielded rather heavy-handedly to suppress alternative or inconvenient viewpoints contrary to the state’s narrative. State policymakers in Russia have typically categorized Islam into what they perceive as traditional, domestic Islam, and the more radical or extremist variant, often associated with foreign influences. This distinction aligns with the broader trend of re-traditionalization and reconservatism in Russian politics, where the state favors a plurality of traditions as long as they are domestically rooted. Consequently, there’s been a concerted effort to support domestic Islamic leaders and restrict foreign engagements, particularly with countries like Saudi Arabia, in efforts to combat what is perceived as Wahhabism.

On another note, regarding the critique of radicalization processes, the Russian discourse on Islam tends to emphasize socioeconomic factors such as poverty and youth unemployment as primary drivers of Islamic radicalization, rather than delving into the political motivations behind the rise of more radical forms of Islam. This stands in contrast to Western perspectives, which often highlight issues of corruption, governance, and centralization, and acknowledge Islam as an ideology of opposition through which disaffected youth express radical dissent against the state. From the official Russian standpoint, such political aspects are often avoided or considered taboo. Instead, their focus lies on addressing poverty, youth unemployment, and implementing policies aimed at bolstering socioeconomic conditions, typically through investment in regions to mitigate vulnerability to radicalization. This approach underscores the significance of socioeconomic improvement as a crucial aspect of addressing the issue.

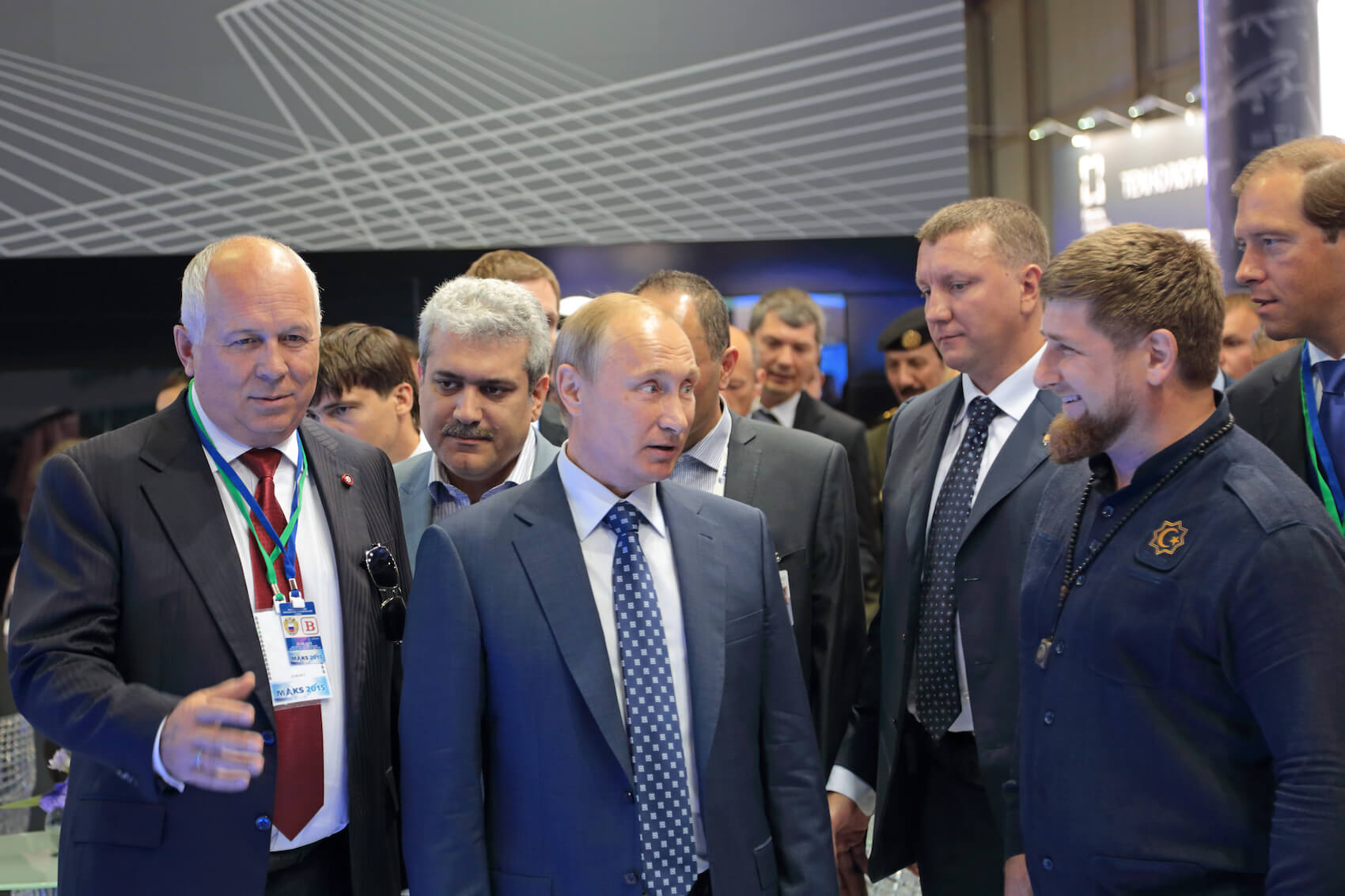

Simultaneously, there are policies of co-option, involving the allocation of funds and support to loyalist supporters. The prime example of this strategy is evident in Chechnya, where Ramzan Kadyrov champions a syncretic form of domestic Islam, albeit one with questionable historical roots. Nevertheless, Kadyrov is perceived as successfully co-opting elements within the region. In terms of foreign policy, Russia has positioned itself as a Muslim power and a friend to the Arab world, particularly after addressing issues in Chechnya and positioning it as a genuine home to Muslims. This shift can also be seen as part of a broader pivot away from Western politics towards a more multipolar approach. As domestic control strengthens, Russia becomes increasingly comfortable presenting itself as a friendly ally to the Arab world.

Russia’s Relations with External Forces Appear More Opportunistic

There’s a widely observed trend of support from Putin’s Russia towards populist, extreme-right-wing parties globally. How do you explain this relationship, and what factors drive Putin to support these parties? Are these connections primarily ideational or opportunistic in nature? Moreover, how has this relationship been influenced by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

Luke March: Overall, Russia’s relations with external forces appear more opportunistic than driven by any consistent ideology. It forms alliances with various groups and individuals for a multitude of reasons, spanning from the radical left to mainstream politicians. Essentially, Russia adapts its messaging to cater to the desires and interests of its audience. However, with the populist right, there’s a discernible ideological component, which has strengthened over time, reflecting Putin’s domestic conservatism. This ideology centers around traditional values, family, church, and robust leadership. In terms of common enemies, the populist right aligns against American hegemony, postmodern liberalism, and views the EU as a supranational actor. This amalgamation of opportunism and ideology is particularly evident in the relationship between Russia and the radical right, where ties are often stronger compared to the radical left. While both may share anti-American and anti-imperialist sentiments, the radical left tends to be more critical of Russia’s domestic model. Conversely, many in the radical right perceive Putin as a symbol of strong, masculine leadership.

The Ukraine war has undoubtedly complicated matters, particularly within Western Europe, making overt support for Russia somewhat taboo. As a result, the stance of the radical right in Europe towards Russia has become geographically divided. For instance, the Finns Party has never been pro-Putin, and now others like the French National Rally have had to reassess their pro-Putin positions, taking a step back and re-evaluating their stance. However, these dynamics are still very much in flux. The war in Ukraine is far from over, and its outcome remains uncertain. This uncertainty means that final alignments are far from settled.

As events unfold, those who have been cautious about openly supporting Putin may gradually shift back towards that position. They may support peace deals while implicitly or explicitly criticizing Western policies such as arming Ukraine and imposing sanctions. Moreover, if Trump secures victory in November, it could significantly bolster the populist right, especially if he follows through on his anti-NATO policies and reduces support for Ukraine. In such a scenario, the radical right may realign towards Russia and begin echoing certain talking points. Overall, these dynamics are still very much in motion and subject to change.

Death of Navalny Sends Message: ‘Imprisonment Is Not the Ultimate Punishment”

What is your interpretation of the recent death of Alexei Navalny in prison, and how does it reflect on the nature of Putin’s regime?

Luke March: There remains a significant amount that we are uncertain about and may never fully understand. The circumstances surrounding Navalny’s death, for instance, remain shrouded in mystery. We cannot definitively determine whether it was orchestrated by someone high up, possibly even Putin himself, or if it resulted from sustained maltreatment during his time in prison, where he faced increasingly harsh conditions endangering his health.

There’s speculation circulating, although its veracity is uncertain, suggesting that Navalny was due for a prisoner exchange, which may have served as a catalyst for his demise. It’s suggested that individuals within the Kremlin deemed such an exchange untenable and thus opted to remove him from the equation. However, these are merely speculative theories, and the truth remains elusive.

However, I believe Navalny’s fate serves as a pivotal indication of the evolving landscape of Russian politics. Just a little over a decade ago, Navalny enjoyed relatively unrestricted freedom to voice his ideas. While he lacked access to state-controlled media, he operated within certain boundaries. Despite occasional arrests or warnings, he even ran in the Moscow mayoral elections in 2013, securing a notable 29% of the vote. At that time, the Kremlin likely perceived him as manageable, perhaps even co-optable, with little cause for concern.

As time progressed, the political climate in Russia grew increasingly restrictive. Navalny was barred from running in the 2018 elections, and he became the target of an assassination attempt, ultimately leading to his imprisonment. This trajectory reflects a trend towards heightened repression and a diminishing tolerance for even limited opposition. While it’s difficult to gauge the extent of Navalny’s potential threat, he never achieved widespread popularity or won a significant election. His influence remained largely potential rather than realized.

By arresting and ultimately leading to Navalny’s death, the Russian government not only displayed its repressive tendencies but also conveyed a message of despair. Navalny, despite his somewhat controversial politics, symbolized a defiance against the Kremlin, a belief that one could stand up to it and even ridicule it without dire consequences. His focus on critical issues like corruption challenged the status quo. However, his demise crushes this sense of hope, suggesting that opposition carries severe consequences. It underscores the message that imprisonment is not the ultimate punishment; there are worse fates awaiting dissenters.

This harsh crackdown also sends a clear message to the West: “We don’t care about your opinions. We disregard Nobel prizes, prominent opposition figures, and any other forms of international recognition."

Some people have suggested that Navalny’s fate indicates Putin’s fear of him. However, I disagree. Putin likely viewed Navalny as an irritant, with those around him perhaps considering him a potential threat if left unchecked. Personally, Putin likely saw Navalny as someone to be crushed without much concern. This illustrates the impunity of power within the Russian political landscape. As seen throughout my earlier responses, a key trend in Russian politics over the past decade and a half has been the increasing dominance of state power and the utilization of state violence.

Elections Serve to Reinforce Putin’s Position

Regarding the upcoming Russian presidential elections next week, do you anticipate any surprises, or do you view it as another milestone in the consolidation of Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian rule?

Luke March: It’s definitely the latter. It seems that any surprises or intrigues in this election are more like minor curiosities rather than significant events. One potential point of interest could be whether the Liberal candidate, Vladislav Davankov, manages to secure second place ahead of the Communists. However, even if this were to happen, it’s likely to represent only a small percentage, perhaps 7, 8, or 9 percent, if even that much. This election appears to be even less competitive than the previous one, which featured three candidates alongside Putin, compared to eight candidates six years ago. None of the candidates seem to advocate for anything particularly substantive. For instance, the Communists have nominated a secondary candidate who also ran 20 years ago and was considered weak even then. Moreover, there are concerns about the fairness of the election process, with indications that it’s pre-rigged. The Kremlin appears to be increasingly relying on Internet and electronic voting methods, which lack proper scrutiny, thereby enabling it to achieve the desired outcome. There’s speculation that Putin could secure as much as 80% of the vote, with purported leaks from within the Kremlin supporting this notion.

If Putin were to secure 80% or 85% of the vote, it wouldn’t come as a surprise, as it leaves virtually no room for opposition. Once again, these elections serve to reinforce Putin’s position as a pivotal figure and patron of the elite. The underlying message he aims to convey is that he is not challengeable in the foreseeable future; while individuals may challenge him, they will inevitably be suppressed. I anticipate no significant deviation from this pattern. Regarding your earlier query about potential weaknesses in the future, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the Russian political system faces vulnerabilities stemming from economic challenges, casualties in warfare, inflation, and other pressures, all of which are unpredictable. However, current measures are aimed at ensuring that no political entity can capitalize on these grievances. Thus far, the Kremlin has been largely successful in this endeavor.