In this timely and incisive interview, Professor Philippe Marlière (UCL) discusses Marine Le Pen’s conviction, the limits of far-right populism, and the resilience of democratic institutions in France. While Le Pen’s narrative frames her disqualification as a “denial of democracy,” Professor Marlière warns against buying into this rhetoric. “Politicians are not above the law,” he asserts, adding, “The far right has no free pass to establish a dictatorship in France.” A must-read on the legal, political, and symbolic stakes of France’s 2027 presidential race.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

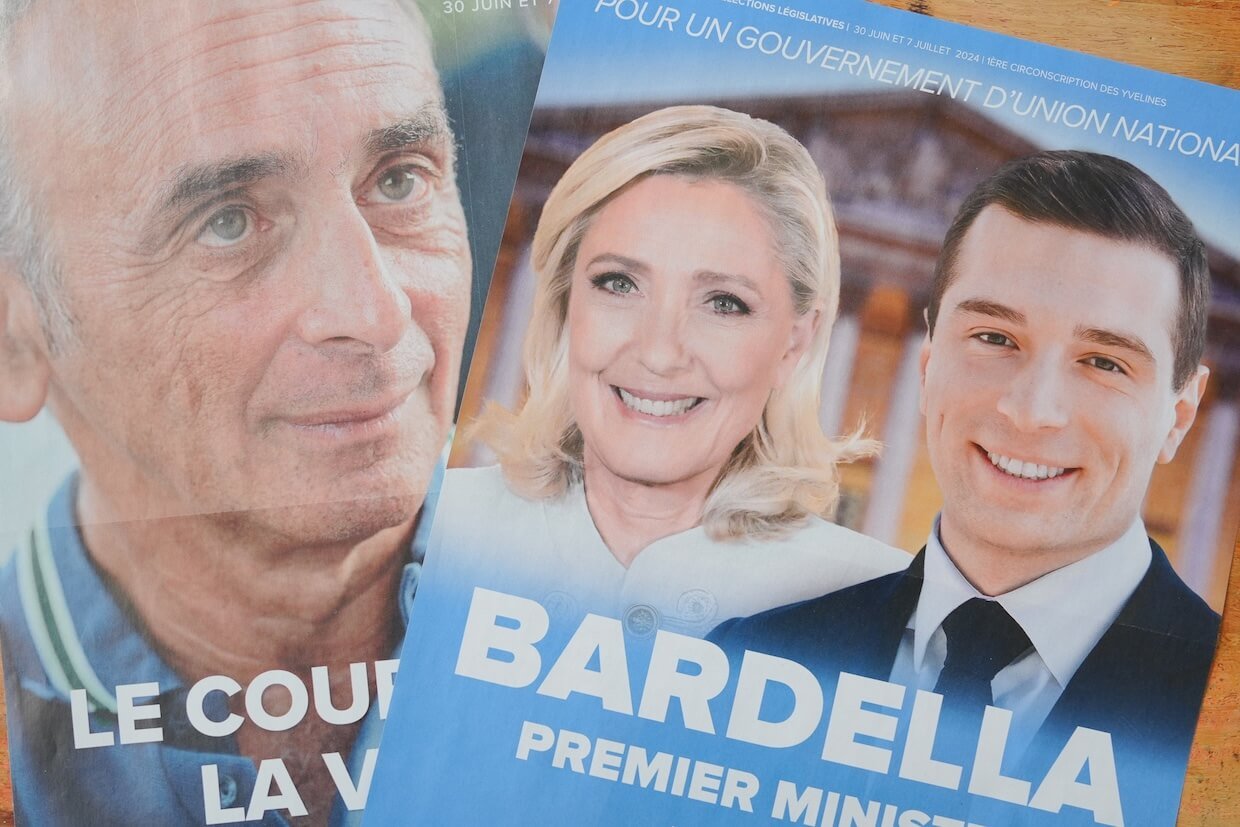

In a wide-ranging interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Philippe Marlière of University College London offers a trenchant analysis of Marine Le Pen’s conviction, the broader rise of the far right in France and Europe, and the fragile boundaries between democratic politics and authoritarian temptation. Known for his work on French and European politics, Professor Marlière opens the conversation by sharply distinguishing between fascism and the far-right populism embodied by Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN). “I would describe Marine Le Pen’s National Rally as a far-right party,” he says, stressing that although it is “reactionary” and “nativist,” it is “not fascist” in the classical sense, since it operates within existing democratic institutions.

The interview takes on greater urgency in the wake of Le Pen’s conviction on corruption charges and her disqualification from running in the 2027 presidential election. According to Professor Marlière, the ruling represents a “major blow” not only to Le Pen personally—who was widely seen as a leading contender—but to the party’s claim of moral superiority over the political establishment. “The conviction is so clear-cut,” he notes, “and her defense so weak,” that overturning the verdict on appeal seems unlikely.

At the heart of the conversation is the far right’s delicate balancing act between anti-establishment rhetoric and the imperative to appear legitimate within democratic norms. Marlière cautions that while Le Pen and her allies may frame the ruling as “a denial of democracy,” they have not dared to attack the judiciary wholesale, because “if she does, she risks being seen as undermining French justice and being pushed back to the political fringe.”

This fragility, he argues, reveals the limits of populist authoritarianism in France. “In a democracy, when you are a politician, you must respect the decisions of the judiciary,” he insists, citing Montesquieu’s separation of powers. And that is why, he concludes, “the far right has no free pass to establish a dictatorship in France.” Voters may be willing to punish the mainstream, but they are not prepared to dismantle liberal democratic institutions in the process.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Philippe Marlière with some edits.

RN Is Nativist, Reactionary, Far-Right—But Not Fascist

Professor Marliere, thank you so very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: You’ve distinguished between authoritarianism and fascism in recent analyses. Given Le Pen’s ideological evolution and her party’s increasing parliamentary power, where would you situate her movement today?

Professor Philippe Marlière: Well, I would describe Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (RN) as a far-right party. If you want to place it on the left-right axis, as political scientists typically do, it clearly falls on the far-right. That’s also how many people in France perceive it today. Le Pen herself resists the "far-right" label, as it implies being on the fringe or extreme end of the political spectrum. However, that is how pollsters and the media commonly categorize the party. So yes, it is far-right.

It’s not fascist. I don’t think the National Rally can be described as a fascist party. Fascism is something quite specific. You can find fascism today in some countries and in some parties, but I don’t think the National Rally is fascist. I would call it nativist. The main concern of the National Rally is the support, through policies, of the indigenous population—the French—as they describe it, as opposed to non-French people or migrants. So: nativist.

Probably reactionary. Much of the National Rally’s policy and ideology seems aimed at returning to a past—often an idealized or even mythical version of the past—that France, in reality, never fully experienced. A past, of course, with fewer migrants and fewer foreigners. In that sense, it is reactionary.

The party used to advocate policies that were decidedly illiberal. For a long time, it supported the death penalty, opposed abortion, and stood against LGBTQ rights. It has evolved on these issues, and that’s likely something we’ll discuss further. In sum: reactionary, nativist, far-right—that’s how I would describe it.

Fascism, as I’ve said, is different. It involves the attempt to establish a totalitarian regime. It can promote racial politics and undermine or directly challenge the rule of law. I don’t believe the National Rally is currently inclined to do that—although, of course, once in power, they might attempt to.

That said, within the current political context, the National Rally appears to be a party that, if elected, would operate within the main institutions of France and Europe. It would likely cooperate with European partners within the European Union. For all these reasons, it is a far-right party, but not a fascist one.

A Major Blow to the RN’s Anti-Establishment Credibility

How do you assess the political implications of Marine Le Pen’s conviction and subsequent disqualification from running for office in 2027? Given the National Rally’s efforts to portray itself as a respectable, anti-corruption alternative to the political establishment, to what extent does this judicial outcome represent a decisive rupture in the party’s quest for power—and could it destabilize its electoral momentum ahead of a crucial presidential race?

Professor Philippe Marlière: Le Pen’s conviction—alongside that of up to 20 party members, mostly elected representatives in the European Parliament—is undoubtedly a major blow. It’s especially significant for Le Pen herself. She might not be able to run in 2027. As far as I’m concerned, I don’t think the decision will be overturned on appeal. She likely won’t be a candidate, so someone else will have to step in.

For now, she’s fighting to clear her name, but the conviction is so clear-cut, the corruption charges so substantial, and both her defense and the party’s defense so weak, in my view, that overturning the verdict will be extremely difficult.

This is a serious setback for Le Pen, particularly because she was seen as having a strong chance of winning the 2027 presidential election. It now seems increasingly unlikely that she will be able to run.

But more broadly, it’s also a significant blow for the party. As you mentioned, it has increasingly been seen as a normalized political force—no longer on the extreme fringe, but rather as a party whose ideas, members, and officials have gradually gained a degree of legitimacy. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it fully belongs to the political mainstream—not yet, not entirely—but to some extent, it is certainly no longer the early National Front of Jean-Marie Le Pen, the party that once frightened a large portion of the public.

So it’s a major blow for the party because part of its appeal lay in being increasingly perceived as no longer extreme by a majority of voters—or at least by a solid base of 37 to 40% of the electorate—while simultaneously remaining highly critical of the system; that is, the other mainstream parties, which it portrayed as corrupt and part of a de facto coalition responsible for poor governance in France and for the French people.

So, of course, being convicted and found guilty of corruption is a major blow, especially since much of Le Pen’s rhetoric has focused on attacking other parties—branding them as corrupt, accusing them of collusion, and portraying them as operating within a deeply flawed system. Now, that very charge is being applied to her.

There is evidence, and according to the first opinion polls, many people now view the National Rally as a corrupt party—or at least believe that the initial conviction handed down by the judges last week was justified.

Politicians Are Not Above the Law

In a democracy, how should we balance judicial independence with the political fallout when a leading presidential contender like Marine Le Pen is barred from running due to financial crimes? Do you see this ruling as reinforcing or undermining public trust in French institutions? Moreover, is there a risk that—even if legally justified—it will fuel far-right conspiratorial narratives about ‘elites’ silencing dissent? How should mainstream parties navigate this moment without inadvertently legitimizing those populist frames?

Professor Philippe Marlière: As you would expect, Le Pen’s defense—and the party’s defense—was to claim that this is a denial of democracy, that the conviction was politically motivated, that the judges are politicized, and that the goal is to bar her from running because she would likely win. That’s what she said at a large rally last Sunday at Place Vauban in Paris. She made these claims, and throughout the week, Le Pen and her supporters have continued to repeat them. Of course, that is their narrative. But that doesn’t mean the narrative is true. In my view, it should be taken with a large pinch of salt and critically examined.

Let’s start with the heart of the matter. What is that? It’s the conviction of Le Pen and her supporters. She is guilty—guilty of a serious act of corruption. Several million euros of public funds were diverted to fake jobs. So we begin with that fact: she is guilty.

However, I believe that, with the support of some media outlets in France—not all, but some—the discussion has shifted away from Le Pen’s conviction and guilt toward a debate about politicized judges and an alleged denial of democracy. I remain very skeptical, if not outright critical, of Le Pen’s narrative, because it seems to me that the judges simply did their job: they applied the law.

By the way, who passed the law—the one that led to Le Pen’s conviction and its immediate effect? It was the lawmakers themselves. A bill was passed in Parliament in 2016. So it was people like Le Pen who voted for that law. They wanted to be extremely harsh on individuals convicted of acts of corruption.

That’s why I think it would be useful to bring the debate back to the heart of the matter: Le Pen’s conviction. She was found guilty of a serious act of corruption. And secondly, the judges simply did their job. To claim that they politicized the process is incorrect—they applied the law.

This also demonstrates something important: politicians are not above the law. They are treated like ordinary citizens—and rightly so. Why should a politician—even someone intending to run for the presidency, with a real chance of winning—be exempt from the law if condemned by French justice?

That’s the real issue. That’s what we should all be reflecting on, instead of defaulting to claims like “the judges are politicized,” and so on. In my view, that is the real question.

Undermining Justice Would Push Le Pen Back to the Political Fringe

Marine Le Pen has characterized her conviction and political ban as a ‘denial of democracy,’ echoing a broader far-right populist tactic of depicting institutions as tools of political repression. In the light of your critique of ‘political nudges’ like the ‘Islamo-gauchisme’ narrative, do you see a danger that the far right will now instrumentalize this legal verdict to delegitimize the French judiciary and fuel deeper mistrust in liberal democratic institutions?

Professor Philippe Marlière: I think it will be difficult to do that. They have probably already tried—particularly Le Pen. If you heard her speak last Sunday in Paris, when she addressed a rally of supporters, she was, of course, very harsh in her response to the judgment. She said, “Of course I’m innocent, this is a denial of democracy,” and so on. She also claimed that the judges who made the decision were politicized.

But she didn’t, so to speak, issue a broader criticism of the French judiciary. She didn’t say, for example, that the entire justice system is corrupt. She avoided that, because doing so would amount to directly challenging the French judicial system as a whole—and that would be quite serious.

It would indeed be highly problematic for a leading contender for the highest office in French politics to undermine the judiciary through such criticism. In a democracy, when you are a politician, you must respect the decisions of the judiciary. Failing to do so means interfering with justice—and that is a very serious matter.

The French political philosopher Montesquieu, in the 18th century, wrote about the separation of powers—executive, legislative, and judiciary—and he said that no power, executive or legislative, should be in a position to interfere with or encroach upon the power of the judiciary. If you do that, it’s no longer a democracy; it’s a tyranny. So justice must remain independent.

That’s why Le Pen will be very careful before launching a broader attack on the justice system. So far, she hasn’t done that. Some of her supporters have likely been less cautious, but she herself has been careful not to place blame on the judiciary as a whole. Instead, she has focused on specific individuals—the judges who issued the ruling—claiming, for instance, that the presiding judge was a leftist.

But this is a difficult line for Le Pen to walk. She cannot push too far in that direction. If she does, she risks being seen as undermining French justice and, as a consequence, being pushed back to the political fringe. Her opponents will say, “Look, you’re clearly not part of the mainstream. If you were ever elected, you would interfere with the justice system.” And that, of course, would be very serious.

Le Pen Must Defend Herself Without Undermining the Rule of Law

Given your work on the ‘dé–diabolisation’ or "de–demonization" of the Rassemblement National and the normalization of the far right in France, do you think Marine Le Pen’s conviction and political ban will disrupt this process—or could it paradoxically bolster her image as a political martyr and reinforce the RN’s anti-establishment appeal? Does this verdict pose a serious challenge to the RN’s attempt to position itself as a credible party of governance, or might it instead deepen its populist narrative of being targeted by a hostile elite?

Professor Philippe Marlière: Again, this is a difficult situation for Le Pen to handle, because she will, of course, try to defend herself. She has already filed an appeal, and I believe it will proceed very quickly—much faster than it would for ordinary citizens. Normally, an appeal takes two to three years, but in this case, it is scheduled for next year, which is unusually swift.

Why next year? Because it allows time for a decision to be made before the presidential election. This gives Le Pen one last chance to run—if she is cleared on appeal. In that sense, it also serves as further evidence that the judges, or the French justice system more broadly, are not conspiring against her. On the contrary, the legal process is offering her another opportunity to stand as a candidate.

So it’s a very difficult situation, because they have to be extremely moderate in their criticism of the justice system; otherwise, they risk being seen as a party that challenges the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary. They simply can’t afford to do that. Someone like Donald Trump may be doing so in the US and getting away with it for now—but in France, where Trump is, by the way, quite unpopular, that approach would not be well received.

So the room for maneuver for Le Pen and her party is quite limited. She can say, “I’m innocent, I’m going to appeal, the judges who made the decision were unfair,” but they cannot go much further than that. They cannot openly criticize the judicial system as a whole.

That’s why I think, in terms of image—since that’s your question—if we look at the initial opinion polls, of course, these will need to be confirmed over time. But according to the polls, people don’t seem to have changed their minds. The party remains quite high in the rankings, and Jordan Bardella appears to have, roughly speaking, the same level of support as Le Pen.

There are two distinct points here. First, it’s clear that the National Rally is currently the leading party in French politics. That was evident in the last two elections—the 2024 European election and the general election—where the party came out ahead of all others.

That’s one thing. The other is the judicial decision. And I think, overall, the opinion polls show that the French public believes the decision was fair. That’s why Le Pen can’t make too much noise about it. It’s seen as a fair judgment. French voters appear to believe that no one should be above the law—including national politicians. If they’ve done something wrong, they should be punished like anyone else would be in similar circumstances.

A Far-Right International Is Emerging—But It Won’t Help Le Pen

In the light of the vocal support Marine Le Pen has received from international right-wing figures like Donald Trump and Elon Musk, to what extent does this signal the emergence of a transnational populist narrative centered on judicial persecution or ‘lawfare’? Are we witnessing a growing global solidarity among populist leaders who frame legal accountability as political victimization by elite institutions and the consolidation of a transnational illiberal alliance?

Professor Philippe Marlière: Well, very likely. The initial signs suggest that there is a kind of de facto reactionary or far-right international that has rallied in support of Le Pen. I think all the major figures—key leaders of that movement in Europe—came out: Orbán in Hungary, Salvini in Italy, Trump, J.D. Vance, Bolsonaro. Many of them made public statements. Even Trump tweeted.

He probably doesn’t know Le Pen very well—perhaps not at all—but someone likely mentioned the case to him, so he tweeted in her support. Of course, he did so because these kinds of far-right leaders seek to undermine the rule of law in liberal democracies. They challenge judicial decisions whenever those decisions go against them, and that’s precisely what Trump has been doing in the US. So, this was more of an opportunity for them to do just that, rather than a genuine expression of support for Le Pen herself.

But yes, there is a de facto far-right international. And every time a decision appears to deprive far-right politicians of power—or simply goes against them—they tend to rally in support of that politician, as they did in this case.

What does that mean, concretely? I think this kind of reaction doesn’t clearly indicate what the future holds, one way or another. It remains very uncertain. When I refer to a far-right international, it shouldn’t be compared to something like the Socialist International, where organized parties met regularly and committed to shared policies. It’s not that structured. It’s more at the level of national leaders or heads of state issuing statements, especially via social media.

So yes, she received that support. But what does it mean for Le Pen in France? I don’t think it means much. As I mentioned, Trump is deeply unpopular in France—on both the left and the right. Almost no one likes him. So I don’t believe receiving support from those far-right figures will benefit Le Pen. I think she has to be very careful. Le Pen wants to be seen as more mainstream, so if she appears to be in cahoots with, or too close to, highly controversial politicians abroad, I don’t think it will help her.

Far Right Is Rising—But Too Divided to Replace Le Pen Easily

From the French perspective, does Le Pen’s downfall create space for a new figure on the European far-right, or is her symbolic centrality too embedded in the populist narrative across Europe to be easily replaced?

Professor Philippe Marlière: This highlights the central challenge facing the far-right in Europe. The far-right has been steadily growing—making electoral gains, winning elections, and even holding power in several countries. To start with Europe: they were in power in Poland; they remain in power in Hungary and Italy—a major EU country—and Le Pen and her party are performing very well in France. The AfD in Germany has also been doing well. So there is a clear, steady rise of the far-right, marked by significant gains in the most recent European elections.

That’s one of the reasons why the far-right is no longer seriously considering leaving the EU if it were to come into power. They’ve realized they can fight from within and attempt to redirect the EU’s political course.

So that’s good news for the far-right. However, does this translate into greater coordination or cohesion among far-right parties and governments in Europe? Not necessarily. For example, there are at least two parliamentary groups in the EU that include far-right parties. They were unable to form a single group, which, of course, weakens their influence because their efforts are divided across multiple blocs.

It’s also well known that far-right leaders do not necessarily get along well; they do not necessarily work together. For instance, Marine Le Pen is close to Salvini and La Lega but doesn’t get along well with the Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni—which is strange, because Giorgia Meloni has a legacy that is more similar to Le Pen’s. They both come from far-right parties initially. Of course, they’ve evolved somewhat and are now a little bit different. But whereas La Lega initially wasn’t a far-right party when it was created in the 1990s, it became a far-right party. So it’s very strange, and I can’t necessarily explain the logic of these de facto alliances between far-right leaders and parties.

I think it often comes down to their positions on policy, but it’s also about whether the leaders get along personally. I believe it’s more the latter. And that, in itself, is telling. Political scientists often say that the left has trouble uniting—and if you look at the French left right now, that’s clearly the case. They can’t come together.

But it seems the far right also struggles to unite, for similar reasons: ideological differences and personal rivalries. So this is where things stand at the moment. The far right has become more successful recently, but it remains divided. It is not a unified movement. Instead, it’s a collection of far-right parties spread across various parliamentary groups in the European Parliament—groups that don’t necessarily cooperate well or work together effectively.

Bardella Isn’t a Le Pen—But He May Be Even More Radical

Jordan Bardella, Le Pen’s protégé, is poised to become her replacement. Based on your analysis of generational shifts within the European far right, do you see Bardella as a mere avatar of Le Penism by remaining dependent on the Le Pen name, or does he represent a potentially more radical or technocratic trajectory?

Professor Philippe Marlière: There are differences between Le Pen and Bardella. First of all, he’s not a Le Pen. If Bardella runs in 2027, it will be the first time since Jean-Marie Le Pen launched the National Front in 1972 that no Le Pen is running for the FN/RN party. That’s the first difference.

There’s also a generational difference. Le Pen is 56, and Bardella’s youth could be appealing—particularly to younger voters—by presenting a new, youthful face of leadership. But of course, there’s a downside: he is politically untested and very inexperienced. He’s not known as a strong debater or a skilled orator. Reaching that level in politics takes time—it requires years of experience. Le Pen has improved over the years, and with Bardella, it would be a very different proposition.

There are also political differences. I think Le Pen has been—and still appears to be—more supportive of the de-demonization strategy. Unlike her father, she hasn’t attempted to shift the party to the center—the National Rally remains firmly on the far right—but she has worked to make some of its flagship policies on immigration, Islam, and the interpretation of French laïcité more acceptable to a broader segment of voters.

To make them more acceptable to other parties as well, because de-demonization works both ways. It involves you, as a far-right party, refraining from using aggressive rhetoric or making racist statements—things that generally do not resonate well with the electorate. But it also involves your opponents shifting to the right and adopting some of your policies, particularly on issues like immigration.

So there are differences, as Bardella appears to be somewhat more radical on those issues. His economic policies also differ; he’s more like Jean-Marie Le Pen of the 1980s and 1990s—more neoliberal, more supportive of laissez-faire economics than Marine Le Pen. So, you might think these are merely cosmetic differences.

And who knows what will happen if we assume that Le Pen won’t run? Bardella seems to be in a good position—he holds a strong position as the party leader. But who knows? Something might change. Other candidates might try to enter the race, and there could even be a primary election within the party.

Think, for instance, of Marion Maréchal, the niece of Marine Le Pen. She left the party a few years ago to join Éric Zemmour, but now she seems to have taken a step back from him as well. She attended the rally on Sunday in Paris in support of Le Pen. Who knows? She’s very popular among party voters. She’s a Le Pen, even though she no longer uses the name—she’s Marion Maréchal-Le Pen—and for that reason, her presence could be significant. She’s also a better orator than Bardella.

So, who knows what might happen? Bardella appears to be the front-runner to replace Le Pen, but we might be in for a surprise.

Le Pen’s Legal Struggles Will Have a Limited Impact on Europe’s Far-Right Strategy

And lastly, Professor Marlière, what ripple effects might Le Pen’s conviction and framing as a martyr have on sister far-right movements in Europe, especially in states like Italy, Hungary, and Germany? Could it embolden them or shift their strategies? Do you think this case and its framing could be used by other European populists to delegitimize legal institutions, especially in countries where the rule of law is already under strain?

Professor Philippe Marlière: I might be a little optimistic on this, but I don’t think it will have a significant impact on the political situations in other countries. Of course, some will use Le Pen’s case to talk about so-called politicized judges, to claim a denial of democracy, to argue that the “true patriots”—as they describe themselves—are being sanctioned by their opponents, that they can’t speak the truth to the people, that they are restricted and constrained. You know, all the usual arguments.

I think they might refer to the Le Pen case in national debates to make those points. But I’m optimistic in the sense that each national context is different. And besides, the pace of politics today is very fast. In a few months, who will still be talking about Le Pen’s conviction?

There will be the appeal, so in a year or so, it may come back onto the agenda. But if the appeal is upheld, I think people will move on—there will be a replacement, another candidate, probably Bardella—and Le Pen will be quickly forgotten.

That’s one thing. The other reason I’m optimistic is that, as I said earlier, Le Pen has to be very careful about criticizing the judges and the justice system—not to be seen as undermining the rule of law—because that would be an extreme move. It would place her in a very radical position, one that most of the electorate, particularly conservative voters who are not far-right, would likely reject.

These are the voters who, in the second round of a presidential election, might be tempted to vote for Le Pen or someone from the National Rally against, for instance, a left-wing candidate—if one were to make it to the runoff. This electorate is conservative, right-wing, but not far-right. The National Rally needs to keep them on board and continue appealing to them. If they can’t—if they lose that electorate—they will never get elected. That’s why they have to be extremely cautious. And I think the situation is the same across most European countries—Italy, probably—with one exception: Hungary.

Hungary has been governed by Orbán for a long time, and many people say that while elections still take place, they are not very fair. It’s a highly authoritarian regime—illiberal. So, probably with the exception of Hungary, where the opposition is now quite weak due to all the laws passed by Orbán’s government, I think in other countries there are still counterpowers—opposition parties, trade unions, the media, and most importantly, the public—the electorate.

It’s not because the electorate is putting the National Rally ahead in France that they want an authoritarian regime. It’s a very complex reality to grasp. I think supporting the far right in France today means, above all, rejecting the other parties—both left and right. People believe those parties were once in power and failed. They tried Macron, and they believe he failed too. So it’s more about the idea: let’s try the only party that has never governed—the National Rally.

But that doesn’t mean voters want an authoritarian regime, or a government that will curb public freedoms or take extreme measures. That’s why Le Pen can’t see herself as the new Trump. I don’t think being a Trump figure would go down well in France. Then again, you might say, in the US, who could have predicted what happened there?

You see, that’s why I’m optimistic. But of course, things can sometimes go wrong very quickly. Still, that’s my view. I think that for Le Pen and the party to be successful and ultimately win an election, they will have to stick to their strategy of de-demonization—which means no longer being seen as an extreme or threatening party—so that enough people will be willing to vote for them.

Of course, they will maintain their policies—against immigration, against Islam, and against a number of other things—but they do so because they believe there is probably a majority of people who could support those positions. Just enough. That’s their strategy. It doesn’t mean they have a free pass to establish a dictatorship in France.