In an in-depth interview with ECPS, Professor Dominika Kasprowicz of Jagiellonian University offers a measured assessment of Poland’s political trajectory following Karol Nawrocki’s narrow presidential victory. While acknowledging the rise of populism and deepening polarization, she maintains that “there is still substantial democratic potential within the system and society.” Professor Kasprowicz highlights the role of affective campaigning, the normalization of populist narratives, and the growing impact of disinformation as structural challenges to liberal democracy. Yet, she points to the resilience of civil society—especially youth and feminist movements—as a critical bulwark against authoritarian drift. “Civic involvement is one of the most important factors behind societal resilience,” she argues, emphasizing the importance of renewed mobilization in the face of rising illiberalism.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In a wide-ranging and analytically rich conversation with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Dominika Kasprowicz—a leading scholar of political communication at the Faculty of Management and Social Communication, Jagiellonian University—offers a nuanced assessment of Poland’s evolving political terrain in the aftermath of Karol Nawrocki’s narrow presidential victory. While acknowledging the rise of populist narratives and affective polarization, she resists the notion that Poland has definitively succumbed to democratic backsliding. “In spite of the many political turbulences along the way,” she states, “I’m convinced there is still substantial democratic potential within the system and society.”

Professor Kasprowicz contends that although Nawrocki’s victory signals a “U-turn” from recent liberal governance, it must be viewed within a broader cycle of disillusionment with the ruling coalition and not solely as an affirmation of authoritarian consolidation. Rather than reading the outcome as a clear-cut shift toward autocracy, she underscores the resilience of democratic institutions and civil society, pointing to the alternation of power as a key indicator: “We saw it happen after the 2023 parliamentary elections, and the recent presidential election also demonstrated this.”

The interview also engages with the civilizational framing and symbolic politics that increasingly shape Polish electoral behavior. Professor Kasprowicz highlights how Nawrocki’s campaign “aligned—both in tone and policy—with figures like Donald Trump and, at times, Viktor Orbán,” tapping into deep-seated cultural cleavages and reframing electoral appeals through affective channels rather than technocratic reasoning. Against this backdrop, she observes that emotions have overtaken policy in shaping political allegiance: “Mr. Nawrocki’s emotionally driven strategy proved more effective… even moderate voters seemed to seek a more assertive, emotionally resonant message.”

Still, Professor Kasprowicz cautions against overlooking structural forces, particularly foreign information manipulation (FIMI), which she describes as “a third actor” in recent Polish elections. Poland, she argues, has become a “testing ground” for new forms of disinformation that remain understudied and underacknowledged politically.

Yet amid the challenges, Professor Kasprowicz finds hope in civil society—particularly youth movements, feminist organizations, and rights-based NGOs. Despite prior government hostility, she emphasizes their enduring relevance: “Engaged, well-trained, highly capable, and deeply connected to European and global networks,” these actors form the backbone of what she terms Poland’s social resilience. Whether this will suffice to resist authoritarian normalization remains uncertain, but one thing is clear: the democratic story in Poland is far from over.

Here is the transcript of our interview with Professor Dominika Kasprowicz, edited lightly for readability.

This Is Not the End of Polish Democracy

Professor Dominika Kasprowicz, thank you so very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: How do you interpret Karol Nawrocki’s narrow presidential victory within the broader trajectory of democratic backsliding in Poland? Does it reflect a recalibration of populist dominance despite the 2023 parliamentary setback for PiS, or does it suggest the consolidation of a hybrid regime model that blends electoral competitiveness with authoritarian resilience?

Professor Dominika Kasprowicz: That’s a very interesting and complex question that has several underpinnings. To answer it, we should start from the very beginning.

As of mid-2025, Poland as a country—and Poles as a society—are in an unprecedented situation and facing unprecedented global circumstances. I believe that the overarching evaluation of both the society and the political system proves that it’s not as bad as is occasionally suggested in the media, particularly across electronic and online outlets.

Let me begin with a brief reminder that for years, especially in terms of economic growth and political developments, Poland has been seen as a frontrunner among the then-new EU Member States. In spite of the many political turbulences along the way, I’m convinced there is still substantial democratic potential within the system and society.

To support this, I would point out that despite the growing cleavage and deepening political polarization, we still observe alternation of power. We saw it happen after the 2023 parliamentary elections, and the recent presidential election also demonstrated this. The course of events suggests that, while the notion of democratic backsliding is certainly a valid concern, at this moment I would not find enough persuasive arguments to fully agree with that interpretation.

Nevertheless, the result of the presidential election—and the victory of Mr. Karol Nawrocki—is clearly a U-turn, following just a few years of a pro-European, more liberal government in power. It was a narrow but decisive win for opposing narratives.

What we often emphasize when commenting on presidential elections in Poland is that, while it’s certainly about the politicians and candidates, it is mostly about the government in power at that time. What I mean is that, to better understand the wider context of this victory—or the lack of victory—it’s crucial to consider the performance or underperformance of the current government.

This growing sense of disillusionment and the slow but steady loss of public support for the coalition government were clearly reflected in the presidential election. Of course, that’s not the only reason for the 2025 electoral outcome, but without including that variable in the analysis, it’s very difficult to fully understand what actually happened.

Civilizational Realignment and Shifting Cleavages Are Redefining Polish Politics

To what extent did Nawrocki’s ideologically coherent messaging and symbolic alignment with figures such as Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán transcend conventional party cleavages and reconfigure voter alignments along deeper cultural or civilizational lines?

Professor Dominika Kasprowicz: It’s an interesting question, because since the early 2000s, what we see in Poland is shifting cleavages and changing trajectories. Until then, it was quite obvious—there was a post-communist versus pro-European sentiment among the electorate. Since the early 2000s, when the formerly aligned center and right-leaning parties became the two main opponents, these cleavages have been changing. This shift is actually happening, and the direction and dynamic are quite interesting.

Over the past 25 years, we’ve seen quite a lot of empirically driven studies and commentary pointing to changing moods and trends within the Polish electorate. Nevertheless, the cleavage I believe is now most salient is the one between traditional and liberal lifestyles, and between more socially oriented or liberal economic worldviews.

What is somewhat surprising—or at least unexpected—is the combination of pro-social yet traditional lifestyle attitudes found on the right or among the populist radical right. In contrast, what is more centrist and liberal in terms of economic views—and pro-European, pro-progressive—belongs to the parties currently governing, including centrist and what remains of the left in Poland.

You asked about civilizational realignment. During the electoral campaign, these were indeed prominent reference points, particularly emphasized by Mr. Nawrocki, who frequently aligned—both in tone and policy—with figures like Donald Trump and, at times, Viktor Orbán. It’s important, however, to analyze these two associations separately. Regarding the US and Donald Trump: beyond personal sympathies, Mr. Nawrocki was, in fact, the only candidate in the campaign to be received—albeit briefly—at the White House. Nevertheless, the meeting did take place.

We must keep in mind Poland’s geopolitical situation—as a country on the so-called eastern flank of the EU and NATO. Despite recent political turbulence in the US, Poland has very limited room for maneuver when it comes to security policy. Poland has long been a close ally of the US. Our NATO membership and the US military presence in this part of Europe have been critically important. I believe both candidates—whether openly or subtly—aligned themselves with the American ally. So, I don’t think anyone here was particularly surprised by Mr. Nawrocki’s open and positive stance toward the US and its president. This broader global security context played a significant role.

When it comes to the Hungarian case and Viktor Orbán, it’s no secret that the former government—as well as the outgoing President Mr. Duda and the Law and Justice Party—maintained friendly relations with Orbán and his party. However, if you look at the actions taken in the European Parliament or the European Commission, the relationship was not always as smooth or friendly as campaign rhetoric might suggest.

Still, the model of strong, charismatic populist leadership remains a point of reference for Mr. Nawrocki—and likely will continue to be. But again, we should take a step back and view the situation from a distance.

Just to remind you: Prime Minister Donald Tusk, later this year, visited Serbia and was actively involved in shaping the priorities of the Polish EU Presidency—including efforts to sustain momentum in the EU enlargement process.

The complex nature of the region, and the growing threat from the East—particularly from Russia—add many shades of grey to the performance of all political leaders, not just the presidential candidates during the June 2025 Polish election.

Emotional Politics Has Overtaken Technocratic Appeals

What structural and discursive limitations inhibited the effectiveness of the liberal-centrist coalition in this electoral cycle? In particular, how might Trzaskowski’s electoral underperformance reflect a broader crisis of technocratic centrism and the limits of rationalist appeals in an emotionally polarized political landscape?

Professor Dominika Kasprowicz: Of course, emotions play a role. This is not only the case in Poland—I believe we are living in an era of emotional politics.

There is a growing body of academic research showing the short- and long-term impact of political messaging, both offline and online, on social attitudes. An interesting aspect of this phenomenon is that a significant part of this process—the persuasive effects on individual and group behavior—often occurs beneath the surface. It is not necessarily a conscious experience for those receiving the message.

We can say that the recent presidential campaign in Poland clearly tapped into pre-existing emotional undercurrents among the electorate. If you examine the main themes of past electoral campaigns in Poland, you’ll notice that none lacked an emotional appeal—often built on imagined threats, mythical enemies, or existing, highly salient cleavages between centrist-liberal voters and those aligned with the traditionalist/populist/radical right.

There is already a strong emotional charge embedded in the political landscape, and Mr. Nawrocki was definitively more effective at triggering those emotions throughout the campaign. By contrast, Mr. Trzaskowski focused on reconciliation. He promised to be a president for all Poles—a unifying figure capable of bridging the deep divisions shaping contemporary Polish society.

So, if you ask whether emotions played a role in the campaign, the answer is unequivocally yes. Mr. Nawrocki’s emotionally driven strategy proved more effective. In times of crisis, war, and growing polarization, even moderate voters seemed to seek a more assertive, emotionally resonant message—which Mr. Trzaskowski’s campaign failed to deliver.

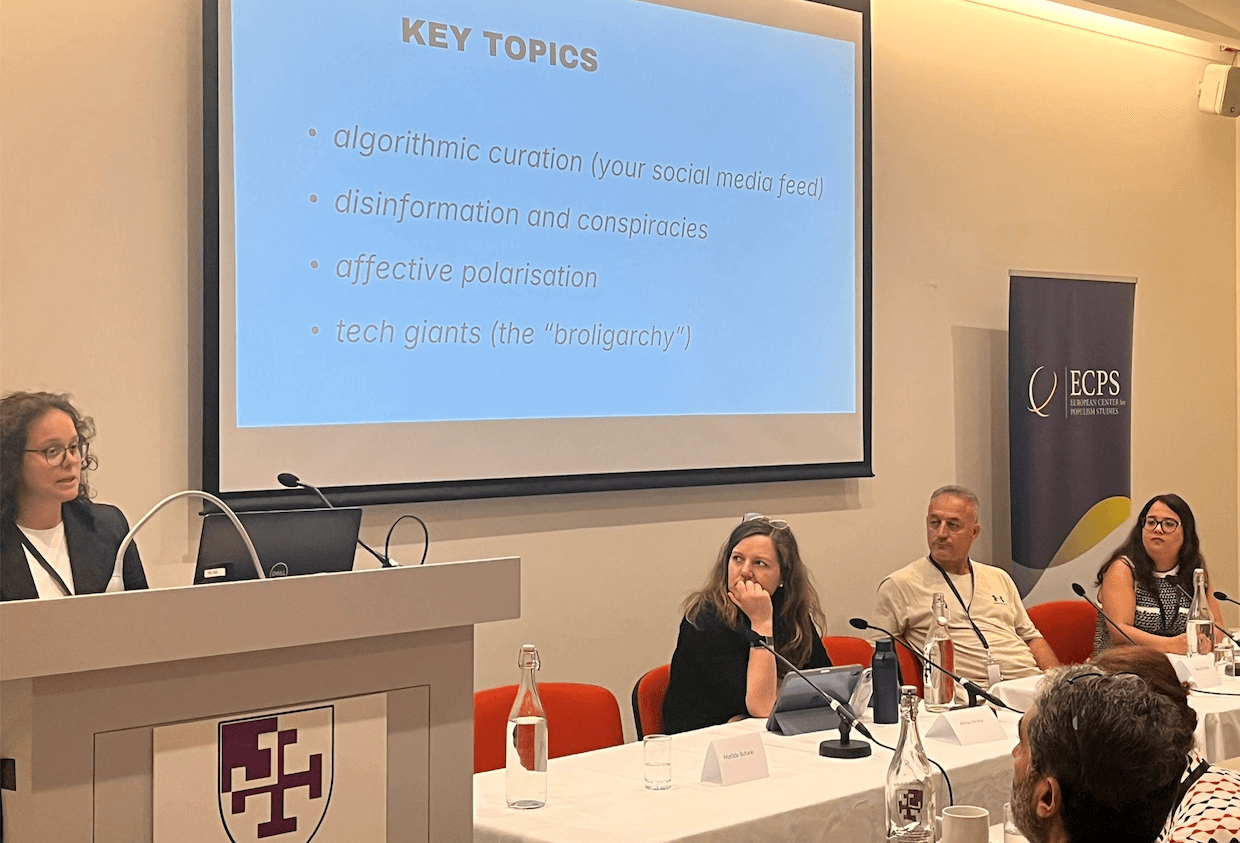

I would also add that there was a significant imbalance between the two candidates in terms of their online presence and social media strategy. Although both were active on popular platforms, it is clear that Mr. Trzaskowski’s team did not prioritize his social media visibility. As we know, social platforms are not only crucial for reaching younger voters but also for shaping narratives, including the spread of false information, disinformation, or misinformation. I believe this was one of the key strategic missteps in Mr. Rafał Trzaskowski’s campaign.

Systemic Constraints Undermine Technocratic Governance

From a political communication perspective, did the 2025 presidential campaign mark a paradigmatic shift from policy-based deliberation to symbolic and affective personalization? If so, how might this transformation affect democratic accountability and voter agency?

Professor Dominika Kasprowicz: Poland is a parliamentary system, which means that while the recent presidential elections—held under a majoritarian formula—are important for several reasons, I would not consider them the most crucial factor in the processes you are asking about.

Nevertheless, considering the prerogatives of the President of the Republic, and the ongoing situation of cohabitation between two opposing sides, this will not contribute to the stabilization of the Polish political system, which has already undergone significant destabilization over the past eight years. By this, I mean the changes that have occurred within the judiciary and media systems, as well as in less visible yet important areas of social and political life, such as education and culture.

If you were to ask what supports or undermines a technocratic model of policymaking, I would point to the systemic obstacles that have been left behind—constraints embedded within the system itself—which continue to prevent its stabilization. By stabilization, I also refer to the difficulty of reversing some of the reforms introduced by the Law and Justice Party during their two terms in power.

Nawrocki’s Campaign Mobilized Memory, Fear, and Identity to Activate a Populist Base

Your work has emphasized the affective potency of populist grievance narratives. How did Nawrocki’s campaign instrumentalize national identity and mnemonic politics to mobilize affective loyalty and consolidate a post-ideological populist base?

Professor Dominika Kasprowicz: Oh, it’s a very interesting question. When you look at the numbers, Poland to this day remains an example of unprecedented success—whether in terms of GDP per capita, quality of life, or the growing quality of infrastructure. Of course, this is a large country with a sizable population, and that doesn’t mean everything is perfect or without problems. Nevertheless, when you consider and compare the situation of the average Polish citizen over the past 20 years—across almost all demographic groups, whether by age, location, or education level—you can observe enormous progress.

Of course, the war in Ukraine, the Russian invasion, and the escalation of conflict have added an additional layer of anxiety, which now influences political attitudes and behaviors. But when you think about the typical populist message and the typical populist voter in Poland today, the external enemy—Russia—is no longer a dividing line. It’s a point of consensus across the political spectrum. Both Nawrocki and Trzaskowski, both Law and Justice and Civic Platform and their coalition partners, agree that Russia poses the greatest threat to Poland. This was also an important element in Nawrocki’s campaign.

Mr. Nawrocki, formerly Director of the Institute of National Remembrance—a public institution responsible for historical archival research and the promotion of Poland’s national narrative—integrated historical memory into his messaging. He strategically appealed to specific resentments and grievances, which, while not shared by the majority of society, still provided fuel for his campaign, depending on the region in which he was speaking. One example is the historical grievance between Poland and Ukraine over the Volhynia massacres during the final years of World War II—mass killings of Polish citizens that remain a sensitive and painful issue. This theme was used to tap into regional resentment. The second element involved anxiety and fear around refugees and illegal migrants—an ongoing and unresolved issue at the Polish-Belarusian border.

As for other grievances, while they may lack strong empirical grounding, they tap into an anti-EU rhetoric aligned with the idea that Poland should maintain as much independence as possible within the EU—prioritizing national interests and resisting pressure, especially from the European Commission.

None of these three elements—historical resentment (e.g., Polish-Ukrainian relations), fear of migrants or refugees, and anti-EU sentiment—are new in Polish politics. They have been present, more or less visibly, for the past 25 years. But they proved effective again, especially when directed at specific segments of Nawrocki’s electorate. I would not say these are overarching or widely shared attitudes across Polish society—on the contrary. Yet they worked for this specific purpose in this specific context.

Disinformation Is Among the Main Actors Shaping Poland’s Political Landscape

Would you argue that the nationalist-populist rhetoric encapsulated in slogans like “Poland First” has become hegemonically embedded in the Polish political imaginary? If so, what counter-hegemonic discursive strategies remain available to liberal-democratic actors?

Professor Dominika Kasprowicz: As I said before, these themes and motifs can be seen as recurring ones. I wouldn’t say that they are of growing importance. What is of growing importance is the changing political environment. And this is an unprecedentedly new framework that we should take into consideration when interpreting the course of political action in Poland.

We haven’t yet touched on a topic that is something of an elephant in the room—disinformation and FIMI (foreign information manipulations), the foreign interference that is present not only in Poland. Nevertheless, Poland should be considered a testing ground for many new strategies of that kind. While we are mostly discussing recent electoral outcomes and the two political figures—Mr. Trzaskowski and Mr. Nawrocki—what is overshadowing not only the Polish elections is, let’s say, a third actor or third agent. And I don’t mean only one country, but rather an important and salient factor behind past and current political developments.

And despite the fact that the long-lasting and very effective impact of disinformation during electoral campaigns has been acknowledged—we have examples and plenty of data coming from Ukraine, but also from other countries such as Georgia, Romania, the Balkan countries, and Slovakia—there is still very little research, and far too little political acknowledgment of the importance of this element.

Civil Society Remains the Backbone of Poland’s Democratic Resilience

And lastly, Professor Kasprowicz, in light of the apparent demobilization among progressive constituencies, what role can civil society—particularly youth movements, feminist groups, and rights-based NGOs—play in resisting authoritarian normalization and restoring democratic engagement?

Professor Dominika Kasprowicz: Let me start with a quick reminder that the parliamentary elections which brought pro-European, more liberal political parties back to power were—putting it simply—won by the youngest voters and by women. This happened with important support from social movements and the NGO sector, which in Poland is large, fairly well institutionalized, and has managed to remain operational despite the previous government’s unfavorable attitude.

It’s not that all NGOs were opposed to the government. Of course, we witnessed the mushrooming of NGOs and mirroring institutions—similar to what we saw earlier in Hungary. But in fact, despite two terms in power, the populist radical right government did not succeed in dismantling the pro-European, liberal-oriented NGO sector, which played a significant role. At the moment, the presence of this segment of society—engaged, well-trained, highly capable, and deeply connected to European and global networks—is of great importance.

On the other hand, when thinking about Polish civil society and the largest NGOs on the ground, they are generally not political. Poles involved in the NGO sector, according to available data, tend to engage more in other forms of activism.

Still, whether political or not, civil involvement—or civic engagement—is one of the most important factors behind societal resilience. And I refer to resilience not only in terms of the political struggle between Law and Justice and the Civic Coalition, but more broadly, as the capacity of society to face global challenges—not just the war in Ukraine and the growing threat from the eastern flank, but also the climate crisis, migration, and other challenges faced by societies worldwide. So, this foundation and interconnectivity of citizens—whether engaged in political or non-political NGOs—is crucial, and it remains intact.

If you ask me whether, in mid-2025, this could serve as a kind of remedy against the rise of populist radical right parties—well, it’s hard to say. As you noted, we are witnessing disillusionment with current policies and growing impatience regarding reforms that were promised but have yet to be delivered. So, it may come down to renewed mobilization—or the search for a political alternative.