Please cite as:

Ferreira Dias, João. (2026). “Opening the Political Pipeline: Transparency and Civic Access to Party Lists as an Antidote to Populist Distrust.” Policy Papers. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). January 15, 2026. https://doi.org/10.55271/pop0006

Abstract

The erosion of trust in liberal democracy – and the dynamic, described by Yascha Mounk, of a growing separation between democracy and liberalism – should be understood in a context of hyper-surveillance, that is, hyper-vigilance and intensified scrutiny. The massification of education and the acceleration and fragmentation of the media environment (online news and social media) have made a persistent social and experiential gap between voters and elected officials increasingly difficult to sustain politically—one that previously drew much of its legitimacy from the formal act of voting and from longer electoral cycles. In this setting, the demand for illiberal solutions emerges plausibly from disenchantment with politics, driven by three factors: (i) civic participation reduced to electoral moments; (ii) thin representative linkages that weaken proximity and blur accountability; and (iii) the perception that political parties function as closed recruitment machines, with internal circuits of elite reproduction and low permeability to merit and to extra-partisan social experience. When integrity failures and scandals compound these conditions, a narrative of moralization and “purification” intensifies and broadens populist repertoires, both in bottom-up variants on the radical left and in broad-based variants on the radical right—directed upward against elites and, at times, downward against minorities and immigrants. The paper’s point of departure is that citizens tolerate delegation when liberal democracy is perceived as functional and fair, particularly in the delivery of the welfare state and in the integrity of fiscal governance. Within a European framework, the paper proposes measures to increase transparency in list formation and open political recruitment (including regulated civic pathways into party lists) as a way to reduce the credibility of populist antagonism and strengthen democratic resilience.

Introduction

Politics and policy – as two sides of the same coin – have become, in the last few decades, increasingly under hyper-surveillance, due to the growth of traditional media and the proliferation of social media. Historically, the media have functioned as the “fourth estate” (after government, parliament, and courts), a long-standing and pervasive concept that translates the social, political, and economic impact of media in modern societies, and that is widely associated with social democratization and political accountability (Schultz, 1998).

But while “citizen journalism” was a foundational idea that dwells in the concept of expanding the role of the citizen as a “watchdog” (Bennett & Serrin, 2005), weblogs and social media became a structural reconfiguration of the information ecosystem. Early blogging ecosystems were often framed as expanding voice and scrutiny beyond traditional gatekeepers, sometimes complementing or contesting mainstream agendas and lowering barriers to agenda-setting (Sánchez-Villar, 2019). However, social media further accelerated the cycle of attention and reward structures around fast, affective engagement, transforming complex ideas into memes, as argued by Yascha Mounk (2023) concerning post-modern theories and their translation into an “identity synthesis.”

The shift from broadcast to participatory media means surveillance is no longer top-down (state over citizens) but multi-directional: citizens monitor elites, and elites monitor public sentiment via data analytics. The hyper-visibility of political life redefines legitimacy and accountability. But social media proved the limits of this participatory media to work as watchdogs as a functional substitute for deliberative scrutiny, promoting slacktivism, a low-cost and symbolic participation (Christensen, 2011), and producing a set of high-cost externalities, including echo chambers, bubbles, misinformation, and hate speech. Importantly, the empirical literature is mixed on whether low-cost online actions crowd out offline engagement; the stronger claim is that platform dynamics can reconfigure incentives, attention, and affect in ways that strain deliberation.

As argued by Cass Sunstein (2017), democracy’s sustainability is at stake due to digital dynamics that undermine the basis of a healthy public sphere. Inspired by Habermas, Sunstein argues that the republic requires different types of citizens to interact and debate, with exposure to diverse arguments, while also prevailing on a common ground. However, the algorithm favors echo chambers and epistemic bubbles that reinforce preconceptions and beliefs, thereby undermining democratic dialogue.

This sketch of the informational ecosystem matters because continuous scrutiny changes how citizens interpret political distance. When everyday monitoring highlights missteps, style, and personal conduct—often detached from policy substance—trust can erode and politics can be read through a moral register. In such settings, accountability is simultaneously intensified (everything is visible) and blurred (responsibility is hard to attribute), creating a demand for clarity that representative institutions rarely satisfy.

This political purity has a strong link to theological backgrounds, since the tension between purity and danger is foundational in Judeo-Christian cultures (Douglas, 1966). Applied to political contexts, the grammar of purity is related to political messianism (Ferreira Dias, 2022) and populist-demagogic leaders (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018) who claim to represent the true voice of ‘the pure people’ (v.g., Ziller & Schübel, 2015; Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2017). In practical terms, “purification” narratives convert institutional distrust into a moral diagnosis (“the system is rotten”) and a moral remedy (“clean it up”), which expands the repertoire of anti-establishment mobilisation.

All this context of “algorithmcracy” (Amado, 2024) puts stress on the democratic system, vulnerable to a range of factors such as economic crisis, political radicalization, and international affairs. Yet the key point for this paper is not that digital dynamics “cause” democratic erosion on their own, but that they magnify the political costs of long-standing representational frictions, especially the gap between who elects and who is elected.

Additionally, democracy is experiencing a singular crisis due to the emergence of illiberal responses, producing a split between democracy and liberalism, as argued by Yascha Mounk (2018). According to the author, since the 2008 economic crisis, native-born citizens have been experiencing a combination of emotional reactions to political, social, and demographic changes. First, a lack of hope among youth generations when comparing their welfare to that of their parents at the same age. Second, intense demographic changes – due to migration and refugee inflows and politicised migration debates – are producing emotional responses both in the US and Europe, with a return to nativist claims (Marchi & Zúquete, 2024; Betz, 2017; Marchi & Bruno, 2016; Guia, 2016) and racial working-class ressentiment (Begum et al., 2021; Carnes & Lupu, 2021; Mondon & Winter, 2020a, 2020b; Morgan & Lee, 2018). Third, a rapid progressive consensus in western societies – the so-called “woke culture,” i.e., and “identity-centred progressive agenda” – placed significant challenges, including strong claims about normative change, in terms of language, literature, and art revision based on (i) personal character of the artist/author versus the creation itself, (ii) current morality seen as the ultimate and correct moral. This led to the re-awakening of immaterial culture wars, with a tension between a cultural left and the cultural backlash of the radical right (Ferreira Dias, 2025; Fukuyama, 2018; Hunter, 1991, 1996).

These pressures converge on a structural vulnerability of representative democracy: the gap between who elects and who is elected. Under hyper-surveillance, that gap becomes easier to see and harder to legitimate—especially when (i) civic participation is largely episodic and confined to elections, (ii) representative linkages remain thin, and accountability is perceived as diffuse, and (iii) party recruitment is experienced as opaque or endogamous, privileging internal pipelines over merit and extra-partisan social experience. When integrity failures and scandals are added to this mix, the resulting moral register (“clean-up” and “purification”) increases the plausibility of populist antagonism and demand for illiberal shortcuts. The remainder of the paper, therefore, develops the political recruitment loop as a mechanism linking hyper-surveillance to democratic disenchantment, and proposes a phased, auditable policy toolbox: minimum transparency standards and civic access pathways into party lists, within a European framework, using Portugal as an illustrative case.

The Problem in Europe: Hyper-Surveillance Meets a Representation Gap

Representative democracy has always rested on a tension: citizens govern themselves only indirectly, by selecting others to make decisions in their name (Pitkin, 1967; Urbinati, 2006). This is a consequence of a long-term political process, related to the transition from absolutist monarchy to democracy (Manin, 1997). While the idea that power lies with the people was essential to desacralize the right to rule, the notion that representation seems to be the most effective way to fulfil the will of the majority leads to discomfort, since the will of the people is only indirectly and highly mediated (Manin, 1997; Przeworski, 2018). In stable periods, that tension is often politically manageable because the legitimacy of delegation is anchored in a simple ritual – elections – and in an expectation that institutions will remain broadly functional and fair between electoral moments (Manin, 1997). In other terms, we may say that people accept the rules of democracy – i.e., being set apart from decisions – if they are gaining from it. It is the economy of political satisfaction (Easton, 1965; Scharpf, 1999).

On the other hand, it leads to a recent, however intense, debate: how representation is limiting representativeness, and how representativeness is a political limitation to parties’ independence (Pitkin, 1967; Urbinati, 2006). In more practical terms, demographic changes are demanding affirmative and corrective actions – like quotas – for Parliament to reflect social diversity (Dahlerup, 2006; Krook, 2009; Phillips, 1995). However, while those affirmative actions are producing results, many social movements are claiming that political actors should act like the citizens rather than being independent (Dovi, 2007; Mansbridge, 2003). For instance, it means that it is not enough to have black people in the parliament, government, and other places, but they should act like activist movements expect them to do (Mansbridge, 1999; Phillips, 1995). This is also applied to other visible traits of politicians, despite the racial aspect making this more evident (Young, 2000).

What Changed: Mass Education and the Acceleration of the Information Ecosystem

First, the massification of education increases the baseline capacity to evaluate political claims and the expectation that power must justify itself continuously. Even when information is imperfect, higher educational attainment broadens the social demand for reasons, transparency, and competence. In practical terms, citizens are more likely to notice inconsistency (between rhetoric and action), opportunism (between promises and constraints), and privilege (between ordinary life and elite trajectories).

Second, a more educated public is also very critical of politicians’ abilities, often being cynical towards what seems to be political careers, especially when they start from a young age and involve limited experience of the real world (Bovens & Wille, 2017; Mair, 2013; Przeworski, 2018). In countries where political parties maintain organized youth wings, it is more likely for citizens to see them as “factories of politicians”, i.e., early entry points that socialize and recruit future candidates, producing greater resentment about the gap between electors and the elected (Jalali et al., 2024; Norris & Lovenduski, 1995).

Third, the media environment shifted from periodic broadcast scrutiny to continuous participatory visibility. Traditional media long operated as a “fourth estate,” associated with accountability and the monitoring of power (Schultz, 1998). But the contemporary cycle is faster and more affective: social media ecosystems reward speed, novelty, and emotional resonance, often compressing complex issues into symbolic conflict. In Mounk’s account of contemporary identity politics, the public arena becomes particularly prone to moralized framings and simplified oppositions, an environment in which political legitimacy is judged not only by outcomes but by conduct, language, and symbolic alignment (Mounk, 2023).

European Symptoms: Low Trust, Party Dislike, and Perceptions of Closure

The European symptom profile is consistent: political parties attract among the lowest levels of trust, and citizens frequently describe politics in terms of closed careers and self-serving elites (Mair, 2013; Przeworski, 2018). In the EU-wide Standard Eurobarometer 101 (Spring 2024), only 22% of respondents “tend to trust” political parties (EU27), while large majorities report distrust (European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication, 2024). Even where trust in other institutions fluctuates, parties remain a focal point for scepticism because they control access to representation: they filter who appears on ballots, how political careers progress, and how internal accountability operates (Hazan & Rahat, 2010; Norris & Lovenduski, 1995).

Perceptions of closure are reinforced where party careers are seen as starting early and progressing through organized youth wings and internal staff roles. While parties tend to see it as a symptom of democracy, citizenship, and generational renovation, public opinion goes on the opposite side, being suspicious of a “jobs for the boys” factory.

Evidence from Portugal suggests an “iceberg-shaped” recruitment ladder: youth wings may be visible as entry points, yet their representation compresses sharply at the decisive stages of candidate selection and electable list placement, with informal bargaining between youth organizations and party leadership shaping outcomes (Jalali et al., 2024). In this sense, anti-establishment narratives are not only moral reactions to individual politicians but institutional reactions to party-controlled filters, what Przeworski (2018) summarizes as the perception that elections reproduce “establishment,” “elites,” or even a political “caste.”

This feeds perceptions aligned with the “cartelization” diagnosis in party scholarship: parties may remain indispensable to democratic coordination while becoming less socially rooted and less permeable to external talent, particularly where public funding and state-linked resources reduce reliance on membership and local embeddedness (Katz & Mair, 1995, 2009; Mair, 2013). Whether or not one adopts the cartel thesis in full, it captures a critical policy-relevant intuition: if citizens experience parties as closed recruitment machines, distrust becomes a rational inference rather than mere cynicism (Hazan & Rahat, 2010; Norris & Lovenduski, 1995).

Finally, the moral register of politics – particularly intense in digital environments –amplifies how integrity failures are interpreted. Scandals do not merely signal individual misconduct; they can erode institutional trust and confirm a broader narrative of closure (“they protect their own”), especially where gatekeeping is opaque (Bowler & Karp, 2004). In that sense, hyper-surveillance often functions less as a neutral accountability tool and more as a lens that magnifies the reputational costs of distance, opacity, and perceived self-reproduction.

A useful contrast is provided by single-member constituency systems such as the United Kingdom. Comparative work on electoral incentives suggests that systems encouraging personal vote-seeking strengthen incentives for constituency-oriented behaviour (Carey & Shugart, 1995), and UK evidence indicates that MPs’ constituency communication and service respond to re-election incentives (Auel & Umit, 2018; Cain et al., 1984; Norton & Wood, 1993). However, stronger constituency linkage does not remove party gatekeeping: candidate selection remains an intra-party process, and perceptions of closure can persist when recruitment is opaque or centrally controlled (Hazan & Rahat, 2010; Norris & Lovenduski, 1995). The implication for European reform debates is therefore precise: improving accountability “at the front end” (representative–constituent linkage) helps, but tackling disenchantment requires reforming the “back end” of democracy: how parties recruit, select, and promote candidates.

Bridge Conclusion

This paper conceptualises the gap between electors and elected as a recruitment loop rather than merely a communication failure. Citizens watch politics continuously but can intervene meaningfully only episodically; they observe parties as gatekeepers but cannot see inside the gatekeeping process. Under these conditions, accountability becomes diffuse and trust costly. Portugal illustrates this dynamic in microcosm: party youth wings function as visible entry points but are seldom translated into real candidate diversity (Jalali et al., 2024). The challenge is therefore to open recruitment without undermining parties’ capacity to coordinate democracy, to make delegation intelligible again. The following section proposes a pragmatic policy toolbox for doing so, balancing transparency, civic access, and organizational integrity (Hazan & Rahat, 2010; Katz & Mair, 1995; Mair, 2013).

Policy Toolbox: Opening without Breaking Parties

The central policy challenge is to widen civic access to representation without undermining parties’ coordinating functions. Parties are not merely electoral vehicles; they aggregate preferences, recruit candidates, structure parliamentary majorities, and make responsibility legible in government (Mair, 2013). Yet when parties are experienced as closed recruitment machines, distrust becomes a rational inference rather than a purely moral reaction, especially under hyper-surveillance, where citizens can observe political life continuously but cannot observe how candidacies are actually made (Hazan & Rahat, 2010; Norris & Lovenduski, 1995). The toolbox proposed here follows a simple logic: make recruitment intelligible (transparency), make entry plausible (civic pathways), and make integrity credible (anti-capture safeguards). These reforms are designed to be phased, auditable, and compatible with freedom of association and party autonomy, principles emphasized in European standards on party regulation (OSCE/ODIHR & Venice Commission, 2020).

First Tool

A first tool is a minimum transparency standard for candidate selection. The aim is not to impose a single “best method” of selection, but to require that parties publish the basic architecture of their recruitment decisions in advance: who decides, by what criteria, on what calendar, and with what right of appeal or review. The OSCE/ODIHR and Venice Commission guidelines underline that party regulation should protect pluralism while encouraging democratic internal functioning and clarity of rules (OSCE/ODIHR & Venice Commission, 2020). Translating this into a practical standard means requiring parties to publish written procedures for list formation (including eligibility, stages, and decision bodies) and to report aggregated outcomes after selection (e.g., number of applicants, share coming from outside internal party roles, and basic diversity indicators, reported in non-identifying form). This aligns with the OECD’s emphasis on openness and inclusiveness as trust-relevant “values” drivers: citizens judge not only outcomes, but also whether processes are fair, transparent, and intelligible (OECD, 2017). Crucially, transparency here is not punitive; it is a low-cost infrastructural reform that reduces the informational asymmetry that makes gatekeeping look arbitrary.

Second Tool

A second tool is to create civic access pathways into party lists, designed to reduce the perception that politics is an insiders’ career ladder. Research on recruitment repeatedly shows that who reaches office depends on filters that operate well before election day, such as party selectors, eligibility rules, and informal networks (Norris & Lovenduski, 1995). The policy aim, therefore, is to add a structured “external entry” channel alongside internal recruitment, without delegitimizing internal party work.

One workable design is a phased system of “civic slots” on party lists, limited in share, clearly defined in eligibility, and tied to an open call. Selection can combine a rule-based screening stage (including blind review where feasible for qualifications and experience), and a plural evaluation panel that includes party representatives plus external members with credibility (e.g., retired judges, academics, civil society leaders). This design reflects the core insight of candidate selection studies: openness alone does not guarantee fairness; the rules of selection and the identity of selectors shape capture risks and public legitimacy (Hazan & Rahat, 2010). To address the predictable objection that “amateurs cannot govern,” parties can attach a standardized training and mentoring track for civic entrants, which preserves competence while changing the optics and reality of permeability.

Third Tool

A third tool is a set of anti-endogamy and integrity safeguards that reduce the probability that openness becomes performative or captured. Here, European integrity standards provide a clear anchor: GRECO’s Fourth Evaluation Round explicitly focuses on corruption prevention for members of parliament, including ethical principles, conflicts of interest, restrictions on certain activities, asset and interest declarations, and enforcement mechanisms (Council of Europe, GRECO, n.d.).

Yet, the toolbox does not require reinventing ethics regulation; it requires connecting recruitment openness to integrity credibility. Practically, parties adopting civic pathways should commit to (i) basic conflict-of-interest declarations for candidates, (ii) simple anti-nepotism rules and disclosure obligations for close family ties in politically relevant appointments, and (iii) clear restrictions on incompatible roles where these create perceptions of insider privilege.

Because parties differ legally across European systems, the policy point is not uniform legal transplantation but a minimum package of auditable commitments that makes “purification” rhetoric less plausible by making integrity rules visible and enforceable.

Fourth Tool

A fourth tool is incentives and certification. One reason reforms fail is that voluntary openness is individually costly for a party, especially if competitors remain closed. A practical solution is a transparency certification: an independent audit against a checklist aligned with the minimum transparency standard, civic access design, and integrity safeguards. This can begin as voluntary and reputational, then become scalable if legislatures choose to connect it to permissible incentives (for example, earmarked public funding for training civic entrants, or additional reporting support), always within the constraints recommended in European party-regulation guidance (OSCE/ODIHR & Venice Commission, 2020). The OECD’s trust framework is relevant here: where citizens perceive institutions as open and aligned with public-interest values, trust becomes easier to rebuild; where processes remain opaque, even good outcomes are discounted (OECD, 2017).

Fifth Tool

A fifth, optional tool is participatory selection mechanisms that do not substitute for parties but complement them. Partial primaries or citizen panels (mini-publics) can be used not to choose entire lists, but to evaluate candidates’ competence and integrity claims in a structured, evidence-based setting. The point is to convert hyper-surveillance into functional accountability: create moments where citizens engage substantively with candidate profiles rather than through algorithmic fragments. Because participatory selection can intensify factionalism or media spectacle, it should be deployed cautiously and only with anti-capture rules and clear scope limits (Hazan & Rahat, 2010).

In sum, taken together, these tools aim to change the political economy of distrust by shifting recruitment from an opaque internal practice to a partially visible civic interface. This is particularly relevant in contexts where youth wings function as visible pipelines, yet the decisive stages of list placement remain compressed and informally negotiated, reinforcing the perception that internal circuits dominate political mobility (Jalali et al., 2024). The toolbox is therefore designed to “open without breaking”: to preserve party coordination while lowering the symbolic and practical distance between electors and elected.

Policy Recommendations, Implementation Roadmap, and Metrics

Recommendations

Recommendation 1 — Adopt a European minimum transparency standard for candidate selection. Parties should publish, ex ante, a written procedure for list formation (eligibility criteria; stages and calendar; decision body; complaint/review channel) and, ex post, an aggregated report on the selection process (e.g., number of applicants; number shortlisted; basic non-identifying diversity indicators; and the share of candidates coming from outside internal party roles). This does not impose a single selection model; it makes gatekeeping legible and therefore contestable on procedural grounds (Hazan & Rahat, 2010; OSCE/ODIHR & Venice Commission, 2020). The expected impact is to reduce informational asymmetry and weaken the plausibility of “closed casta” narratives under hyper-surveillance (European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication, 2024; Mair, 2013).

Recommendation 2 — Implement phased civic access pathways (“civic slots”) into party lists. Parties should reserve a limited and gradually expandable share of list positions for candidates recruited through an open call, with eligibility rules that allow genuine external entry (Norris & Lovenduski, 1995). Selection should be rule-based and staged: a first screening phase can be partly blinded where feasible (qualifications, experience), followed by a plural evaluation panel combining party and external members with high credibility. This targets the core driver of disenchantment identified in recruitment research: citizens can vote, but they cannot realistically enter the pipeline (Hazan & Rahat, 2010; Norris & Lovenduski, 1995).

Recommendation 3 — Add anti-endogamy and integrity safeguards that make openness credible. Where recruitment opens, the system must also signal credible integrity boundaries: baseline conflict-of-interest declarations for candidates; simple anti-nepotism disclosure rules; and enforceable incompatibility rules where accumulation of roles creates perceptions of insider privilege. These measures align with European anti-corruption frameworks that emphasize conflicts of interest, codes of conduct, and enforceability for MPs (Council of Europe, GRECO, n.d.). The expected impact is to prevent openness from being dismissed as symbolic and to reduce “purification” dynamics that thrive on scandal amplification.

Recommendation 4 — Create a transparency certification (voluntary first, scalable later). An independent audit against a short checklist (procedural transparency; civic pathway design; basic integrity disclosures) can generate reputational incentives while limiting the collective-action problem where no party wants to “disarm” unilaterally. This is a policy instrument, not a European legal requirement; it is justified by the governance literature on rebuilding trust through competence and values (OECD, 2017).

Recommendation 5 — Publish annual aggregated metrics to track whether pipelines are actually opening. Parties (or an independent public body) should report a small set of comparable indicators annually (see below). This shifts debate from moral accusation to measurable change and allows phased reforms to be evaluated and adjusted (OSCE/ODIHR & Venice Commission, 2020).

Implementation Roadmap (0–48 months)

In months 0–12, implement the minimum transparency standard (Recommendation 1) and launch a pilot civic pathway with a small number of civic slots (Recommendation 2), accompanied by a basic integrity package (Recommendation 3). In parallel, start the voluntary certification scheme (Recommendation 4) and define the common reporting template (Recommendation 5).

In months 12–24, expand civic slots modestly (conditional on applicant volume and audit results), institutionalize the plural panel model, and introduce routine disclosure checks (lightweight, standardized, and auditable).

In months 24–48, consolidate reforms: embed transparency and reporting as stable practice, commission an independent evaluation, and recalibrate thresholds (slot share, screening rules, disclosure scope) based on observed capture risks and legitimacy gains.

Portugal can remain an illustrative benchmark rather than a dedicated section: recent evidence on the translation from youth recruitment to electable list placement shows why “pipeline visibility” does not automatically equal “pipeline openness,” and why reforms must target the decisive stages of selection (Jalali et al., 2024).

Metrics & Evaluation (minimal set)

A compact metrics package should track: (1) the share of elected officials with substantial professional experience outside party/political roles (aggregated); (2) average tenure and rotation rates in elected office; (3) number of applicants per civic slot and selection rates; (4) compliance scores on the transparency checklist (party-level, annually); and (5) time-series trends in trust in parties (national and EU benchmarks, including Eurobarometer) (European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication, 2024).

Conclusion

Hyper-surveillance did not create Europe’s representation gap, but it has raised the political cost of long-standing features of representative government: mediated will-formation, professionalized political careers, and party gatekeeping. When citizens can monitor politics continuously yet cannot observe – or access – the recruitment process, accountability becomes diffuse and trust becomes costly. The policy aim is therefore not moral “purification,” but infrastructural repair: opening the political pipeline while preserving parties’ coordinating capacity. A minimum transparency standard, civic access pathways, and credible integrity safeguards together can transform hyper-vigilance into functional accountability, reducing the plausibility of populist antagonism and strengthening democratic resilience (Hazan & Rahat, 2010; Mair, 2013; OSCE/ODIHR & Venice Commission, 2020).

References

Amado, M. A. N. (2024). Algoritmocracia: Utopia, Distopia e Ucronia. Editora Dialética.

Auel, K., & Umit, R. (2018). Explaining MPs’ communication to their constituents: Evidence from the UK House of Commons. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20(3), 731–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148118762280

Begum, N., Mondon, A., & Winter, A. (2021). Between the ‘left behind’and ‘the people’: Racism, populism and the construction of the ‘white working class’ in the context of Brexit. In Routledge handbook of critical studies in whiteness (pp. 220-231). Routledge.

Bennett, W. L., & Serrin, W. (2005). The watchdog role. In G. Overholser & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.), The institutions of American democracy: The press (pp. 169–188). Oxford University Press.

Betz, H. G. (2017). Nativism across time and space. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 335-353.

Bovens, M. A. P., & Wille, A. (2017). Diploma democracy: The rise of political meritocracy. Oxford University Press.

Bowler, S., & Karp, J. A. (2004). Politicians, scandals, and trust in government. Political Behavior, 26(3), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POBE.0000043456.87303.3a

Cain, B. E., Ferejohn, J. A., & Fiorina, M. P. (1984). The constituency service basis of the personal vote for U.S. representatives and British members of parliament. American Political Science Review, 78(1), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961252

Carey, J. M., & Shugart, M. S. (1995). Incentives to cultivate a personal vote: A rank ordering of electoral formulas. Electoral Studies, 14(4), 417–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-3794(94)00035-2

Carnes, N., & Lupu, N. (2021). The white working class and the 2016 election. Perspectives on Politics, 19(1), 55-72.

Christensen, H. S. (2011, February 7). Political activities on the Internet: Slacktivism or political participation by other means? First Monday, 16(2). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3336

Council of Europe, Group of States against Corruption (GRECO). (n.d.). Fourth Evaluation Round: Corruption prevention in respect of members of parliament, judges and prosecutors. https://www.coe.int/en/web/greco/evaluations/round-4

Dahlerup, D. (Ed.). (2006). Women, quotas and politics. Routledge.

Douglas, M. (1966). Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. Routledge.

Dovi, S. (2007). The good representative. Blackwell Publishing.

Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life. John Wiley & Sons.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication. (2024, May 23). Standard Eurobarometer 101 – Spring 2024.

Ferreira Dias, J. (2022). Political messianism in Portugal, the case of andré ventura. Slovenská politologická revue, 22(1), 79-107.

Ferreira Dias, J. (2025) Guerras Culturais: os ódios que nos incendiam e como vencê-los. Lisboa: Guerra e Paz.

Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identity: Contemporary identity politics and the struggle for recognition. Profile Books.

GUIA, Aitana, The concept of nativism and anti-immigrant sentiments in Europe, EUI MWP, 2016/20 – https://hdl.handle.net/1814/43429

Hazan, R. Y., & Rahat, G. (2010). Democracy within parties: Candidate selection methods and their political consequences. Oxford University Press.

Hunter, J. D. (1991). Culture wars: The struggle to control the family, art, education, law, and politics in America. New York: Basic Books.

Hunter, J. D. (1996). Reflections on the culture wars hypothesis. In J. L. Nolan Jr. (Ed.), The American culture wars (pp. 37-58). University Press of Virginia.

Jalali, C., Silva, P., & Costa, E. (2024). Youth with clipped wings: Bridging the gap from youth recruitment to representation in candidate lists. Electoral Studies, 88, 102767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102767

Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (1995). Changing models of party organization and party democracy: The emergence of the cartel party. Party Politics, 1(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068895001001001

Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (2009). The cartel party thesis: A restatement. Perspectives on Politics, 7(4), 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592709991782

Krook, M. L. (2009). Quotas for women in politics: Gender and candidate selection reform worldwide. Oxford University Press.

Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies die: What history tells us about our future. Crown.

Mair, P. (2013). Ruling the void: The hollowing of Western democracy. Verso.

Manin, B. (1997). The principles of representative government. Cambridge University Press.

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should Blacks represent Blacks and women represent women? A contingent “yes”. The Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657.

Mansbridge, J. (2003). Rethinking representation. American Political Science Review, 97(4), 515–528.

Marchi, R., & Bruno, G. (2016). A extrema-direita europeia perante a crise dos refugiados. Relações Internacionais, (50), 39-56.

Marchi, R., & Zúquete, J. P. (2024). Far right populism in Portugal. Análise Social, 59(2 (251), 2-19.

Mondon, A., & Winter, A. (2020a). Whiteness, populism and the racialisation of the working class in the United Kingdom and the United States. In Whiteness and nationalism (pp. 10-28). Routledge.

Mondon, A., & Winter, A. (2020b). Reactionary democracy: How racism and the populist far right became mainstream. Verso Books.

Morgan, S. L., & Lee, J. (2018). Trump voters and the white working class. Sociological Science, 5, 234-245.

Mounk, Y. (2018). The people vs. democracy: Why our freedom is in danger and how to save it. Harvard University Press.

Mounk, Y. (2023). The identity trap: A story of ideas and power in our time. Penguin Group.

Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Norris, P., & Lovenduski, J. (1995). Political recruitment: Gender, race and class in the British Parliament. Cambridge University Press.

Norton, P., & Wood, D. M. (1993). Back from Westminster: British members of parliament and their constituents. University Press of Kentucky.

OECD. (2017). Trust and public policy: How better governance can help rebuild public trust. OECD Publishing.

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), & European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission). (2020). Guidelines on political party regulation (2nd ed.). Council of Europe. https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2020)032-e

Phillips, A. (1995). The politics of presence. Clarendon Press.

Pitkin, H. F. (1967). The concept of representation. University of California Press.

Przeworski, A. (2018). Why bother with elections? Polity Press.

Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and democratic? Oxford University Press.

Schultz, J. (1998). Reviving the fourth estate: Democracy, accountability and the media. Cambridge University Press.

Sunstein, C. R. (2017). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton University Press.

Urbinati, N. (2006). Representative democracy: Principles and genealogy. University of Chicago Press.

Young, I. M. (2000). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford University Press.

Ziller, C., & Schübel, T. (2015). “The pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”? Political corruption, political trust and the success of radical right parties in Europe. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 25(3), 368-386.

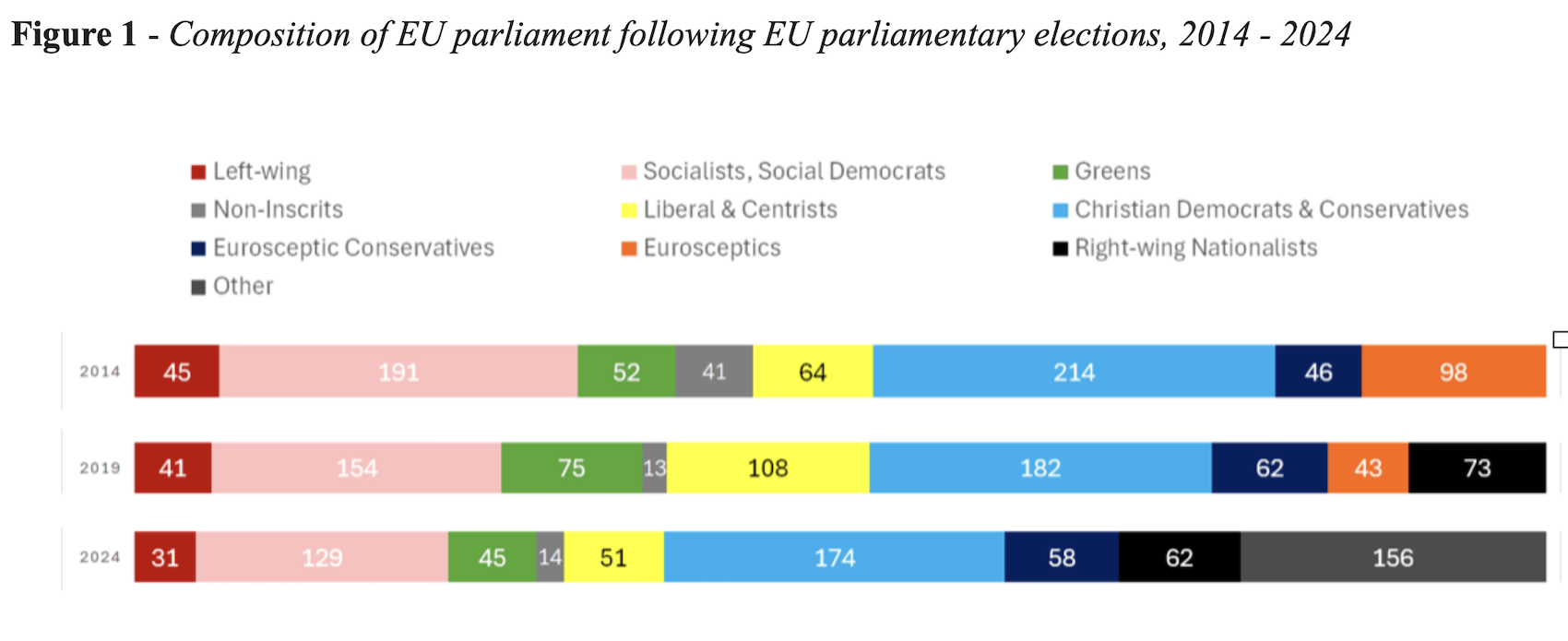

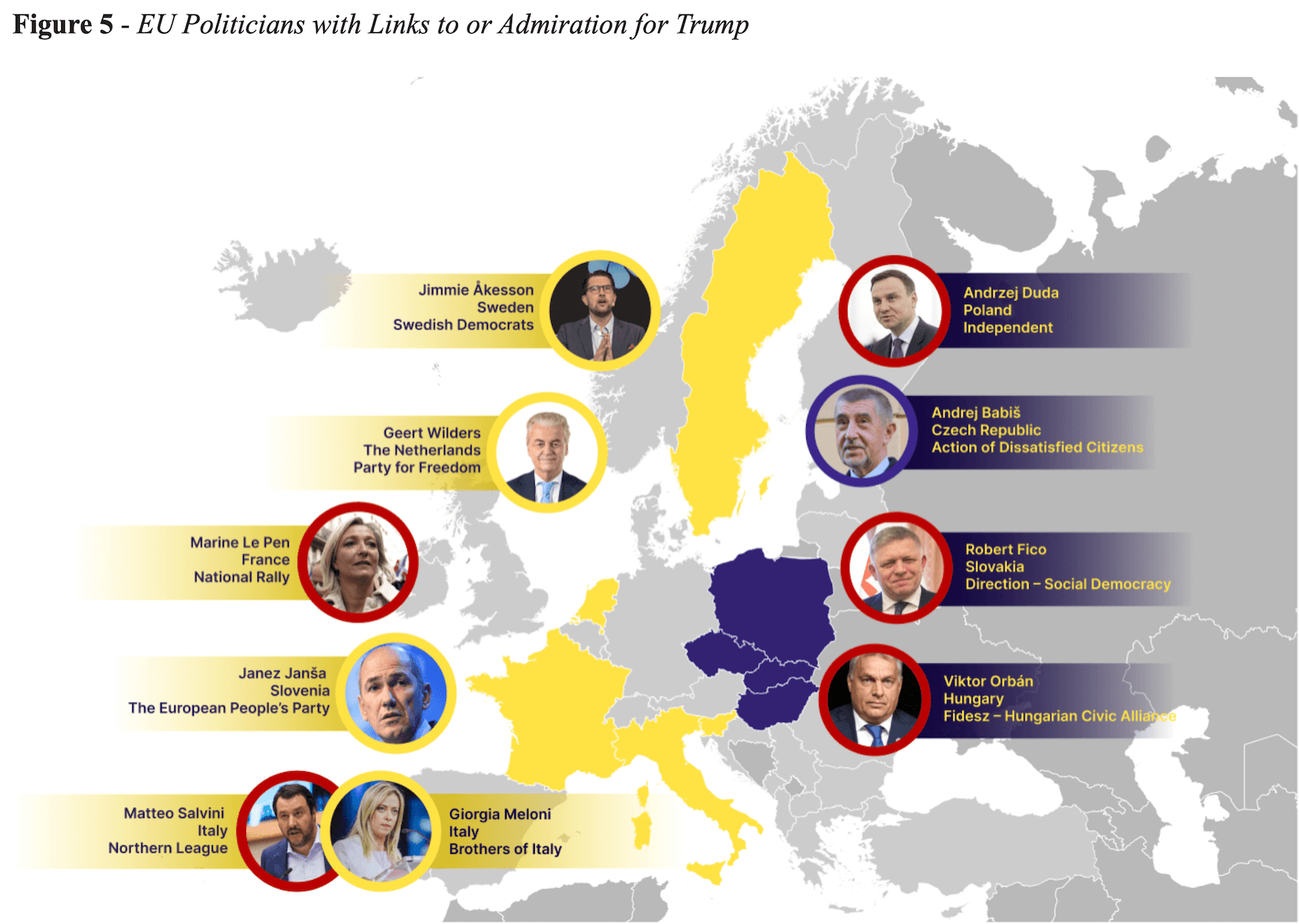

Europe has also faced difficulties controlling the increasing numbers of its migrant population. According to the International Organization for Migration (McAuliffe & Oucho, 2024), there are approximately 87 million migrants living in Europe. In the context of migration crises, which often disproportionately impact EU member states, balancing European cohesion has fragmented the Union. Additionally, in recent years, Western politics has witnessed a trend of a right-wing shift (see Figure 1) and increased support for populist leaders, which exacerbates this fragmentation (Europe Elects, 2024; Europe Politique, 2024).

Europe has also faced difficulties controlling the increasing numbers of its migrant population. According to the International Organization for Migration (McAuliffe & Oucho, 2024), there are approximately 87 million migrants living in Europe. In the context of migration crises, which often disproportionately impact EU member states, balancing European cohesion has fragmented the Union. Additionally, in recent years, Western politics has witnessed a trend of a right-wing shift (see Figure 1) and increased support for populist leaders, which exacerbates this fragmentation (Europe Elects, 2024; Europe Politique, 2024).