Please cite as:

Carls, Paul. (2024). “Right-wing Populism in Luxembourg During the 2024 EP Election.” In: 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism. (eds). Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina. European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS. October 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0078

DOWNLOAD REPORT ON LUXEMBOURG

Abstract

Right-wing populism in Luxembourg is largely confined to the Alternative Democratic Reform Party (Alternativ Demokratesch Reformpartei, ADR). The name is, however, a bit of a misnomer. While ideologically, the ADR maintains national–conservative positions consistent with other European right-wing populist parties, its views are not as extreme. The party retains relatively constant support, consistently gaining around 10% of the vote in national elections; in the 2023 election for the Chamber of Deputies, it gained 9.3%, while in the 2019 European Parliament election, the party gained 10%, just short of enough to obtain a seat. Given the rise in support for right-wing populist parties in other European countries (e.g., the AfD in Germany or the National Rally in France), the ADR was optimistic about its chances of gaining its first-ever seat in the European Parliament, which would require about 12% of the vote total. This contribution will investigate the results of the European Parliament election in Luxembourg, focusing on the ADR. It will discuss any ideological shifts in the party as well as its positioning on a host of issues where one finds a prominent voice for right-wing populist parties in Europe, including NATO, the war in Ukraine, migration, COVID-19 or the functioning of the European Union. The entry will also address the results of the election to determine how strong support for right-wing populism in Luxembourg is. Other relevant aspects of the election (e.g., campaign events, media coverage) will be discussed if they featured prominently in the campaign.

Keywords: ADR; Luxembourgish; European integration; transnational migration; Luxembourg Compromise

By Paul Carls (Independent Researcher, PhD Université de Montréal)

Background

Luxembourg is not a country known for right-wing populism. With a population of 672,000, roughly half of whom hold foreign nationality (STATEC, 2020), it is a small and internationally integrated country that benefits greatly from the trends of globalization that many right-wing populists denounce; the country is highly integrated politically in the European Union, its economy is heavily dependent on international financial and economic integration, and its economy similarly is heavily dependent on an international and transnational worker base, many of whom travel daily to Luxembourg from neighbouring countries (Carls, 2023; de Jonge, 2021; Fetzer, 2011). Luxembourg does, nevertheless, have a party that maintains a right-wing populist profile and that has had electoral success, the Alternative Democratic Reform Party (Alternativ Demokratesch Reformspartei, ADR). The party formed in 1987 as the Aktiounskomitee 5/6 Pensioun fir jiddfereen (Action Committee 5/6ths–Pensions for Everyone) to campaign on the single issue of pension reform and in 1992, changed its name to Aktiounskomitee fir Demokratie a Rentegerechtegkeet (Action Committee for Democracy and Pension Justice). In 1999 the party received its greatest success to date in the national general election with 11.3% of the vote, although pension reforms in 1998 and 2002 made the single issue of pension reform less pressing (Schulze, 2006). The ADR then evolved into a catch-all party, adopting its current name in 2006.

In 2015 it gained prominence in the campaign surrounding a referendum to amend the constitution to allow, among other things, non-Luxembourgish residents to vote in general elections for the Chamber of Deputies, Luxembourg’s national legislative body. The election result showed that between 70% and 80% of the population rejected the proposed constitutional modifications. The ADR was notably the only elected party to oppose the proposed reforms (Carls, 2023). In the 2019 European Parliament (EP) election, the party gained 10%, just short of enough to obtain a seat, while in the most recent general election in 2023, the party received 9.27% of the vote and gained 5 seats in the 60-seat Chamber of Deputies.

Ideologically the party maintains a national–conservative profile with flavours of classical liberalism that seeks a broad appeal, including to the working class. In the 2023 general election, for example, the party criticized ‘gender ideology’ or the push for transgender recognition but also supported legalizing prostitution. The party generally maintains a distrust of big government, whether economically or in terms of individual freedom, consumer rights or bodily autonomy, as was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic (ADR, 2023), but also supports government protection of special working privileges for Luxembourgers, which sees well-paid government jobs going only to those with a high proficiency of Luxembourgish, a position with broad appeal among the electorate (Carls, 2023).

There is no consensus as to whether the ADR is a right-wing populist party, with some saying yes (Blau, 2005; Carls, 2023; Zulianello, 2020) (although these authors generally note that the variety of populism exhibited by the ADR is mild or atypical in comparison with other European cases) and some saying no (Camus, 2017; Poirier, 2012). Such confusion stems from the fact that, due to Luxembourg’s specific socioeconomic situation, a right-wing populist party in the style of the National Rally or the Freedom Party of Austria is likely electorally impossible, leading the ADR to adopt comparatively softer stances on important issues. The ADR is by no means in favour of an exit from the EU, for example, and while it is in many respects critical of both the EU and multiculturalism, such critiques are often modulated by words of praise for the positive benefits the EU and immigration have brought to Luxembourg (Carls, 2023; de Jonge, 2021).

Nevertheless, it shares many of the same positions and preoccupations as other right-wing populist parties in Europe (including migration, Covid policies, free speech, retaining national sovereignty within an EU institutional framework, etc.) and is a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group in the EP, which includes the well-known Law and Justice Party (PiS) from Poland, the Brothers of Italy (led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni), and the Sweden Democrats (Carls, 2023; Lamour & Carls 2022). These facts, coupled with the lack of a suitable alternative, suggest that any exploration of right-wing populism in Luxembourg must focus on the ADR.

Heading into the 2024 EP election, the ADR’s lead candidate was Fernand Kartheiser, a former military officer and diplomat and a member of the Luxembourgish Chamber of Deputies for the ADR since 2009. The party prioritized several issues: the functioning of EU institutions, maintaining the 1966 Luxembourg Compromise or the veto power of countries regarding decisions deemed of vital national interest, migration policies, the preservation of the combustion engine or the opposition to green politics more generally, and concerning the war in Ukraine, a politics of peace in Europe.

ADR positioning during the election: The supply side

Following a minimalist definition according to which populism is ‘an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde, 2017: 29), the ADR’s framing of issues during the 2024 election was broadly populist. Right-wing populism contains a further nationalist dimension (de Cleen, 2017; Mudde, 2007; Rydgren, 2007; 2017; Taguieff, 2015), also present in the ADR’s electoral framing. This additional element leads to a set of exclusions on the vertical axis (people–elite) and the horizontal axis (people–outsiders) that is characteristic of right-wing populist discourse and was visible in the ADR’s advocacy for a ‘Europe of sovereign nations’ (ADR, 2024a: 1).

Much of the ADR’s policy positions and profile as a right-wing populist party in the EP election can be summed up in a passage from their EU electoral program: “The ADR must note with regret that the EU has also fundamentally changed politically in recent years. Obvious violations of the rule of law in the Covid Crisis, the war in Ukraine with sanctions against Russia that drive up energy prices and destroy European competitiveness, the high inflation that is also linked to the monetary policy of the ECB, a militant and harmful green policy in the field of energy and industry, a still massive and unbridled illegal immigration in Europe, accusations of corruption, including against the President of the European Commission, a diffuse and contradictory accession policy, limitations of freedom of expression and institutional threats not only from the EU institutions but also from increased German and French hegemonic efforts are only a few of the many challenges we face. These and many other problems have progressively made it more and more difficult for the European Union to present a facade of unity to the outside world. The European institutions have not caught up with how far they have already moved away from the people” (ADR, 2024a: 17).

This passage encapsulates the vertical and horizontal exclusions typified by right-wing populism and remains consistent with the ADR’s positions in past years. Luxembourgers and other European nations are represented by the idea of the ‘people’. They are opposed vertically by a left-wing dominated and increasingly autocratic EU and horizontally by ‘unbridled illegal immigration’ from the third world.

The vertical exclusions pitting the ‘people’ against elites was the most salient aspect of the campaign positioning and was visible on the following issues, which the ADR emphasized during its campaign. The first is federalism. The ADR fundamentally opposed efforts at EU federalism or a strongly centralized federal EU state that takes competencies away from the member states. The party notably criticized ‘Brussels bureaucrats’ who take power away from ‘the people’ in their nation-states (ADR, 2024a: 1). In line with its opposition to a federal state and support for national sovereignty, the ADR strongly supported the unanimity principle or the veto power of countries in the European Council regarding decisions deemed of vital national interest. Of note is the importance of this principle as it concerns Luxembourg’s financial and taxation systems.

The ADR also condemned Brussels’ attempts to isolate member countries with which it has important conflicts. Such conflicts surround refugee and migration policies, family policies and changes in national legal procedures. They have often involved members of the Visegrad Group, most notably Poland and Hungary. The ADR framed such conflicts as a result of a clash of wills – namely, that of ‘the people’, which democratically elects politicians to enact specific policies, and that of the ‘unelected’ EU (ADR, 2024a: 7).

The ADR strongly supported the principle of free speech and saw it under threat from left-wing activists and EU regulation. It spoke specifically of the Digital Services Act, an EU regulation designed to promote transparency of online services. While such efforts aimed to fight disinformation and defend democracy, the ADR argued that such measures actually demonstrated that the EU was increasingly less tolerant of voters who have the ‘wrong’ opinions or vote for the ‘wrong’ politicians (ADR, 2024a: 7).

The ADR also equated the EU with ‘experts’ who push a radical green–left ideology onto member states in an undemocratic way. The ADR saw such policies as a way to grant ever-greater competencies to the EU, arguing that decisions around environmental regulation should be left to national states (ADR, 2024a: 9). EU policies in this area, the party argued, have led to economic hardship and undermined innovation. The party made a particular point of the EU’s decision to ban the sale of internal combustion engines by 2035, a decision it called ‘extremist’ (ADR, 2024a: 21).

While the ADR strongly condemned the Russian attack on Ukraine (ADR, 2022), the party took a position of peace concerning the war in Ukraine. Recognizing the complexity of the situation and the relevance of Ukraine geopolitically, the party called on the EU not to intensify a conflict that would only serve to destroy Ukraine. It also criticized Brussels for not abiding by the Minsk Accords and reproached the EU for utilizing the conflict to push a federalist agenda, in this case concerning European defence (ADR, 2024a: 4). The party was also somewhat sceptical of Ukraine’s ability to join the EU, noting that it fulfilled none of the Copenhagen criteria and should not be accepted without an exhaustive accession process (ADR, 2024a: 36).

The ADR was critical of continued, uncontrolled migration to Europe from largely third-world or war-torn countries. In this respect, the EU has been leading a failed migration policy since 2015, which has led to a significant loss of trust in the EU and substantial illegal immigration, including economic migrants masquerading as refugees. The ADR called for a humane policy that granted asylum but reduced migratory flows and prevented illegal immigration.

Another point that the ADR made during the campaign was to advocate for the recognition of Luxembourgish as an official EU language. Such recognition was important as it would recognize Luxembourg as a unique country with its own history and culture. As such, the ADR appealed to Luxembourgish national pride.

Despite their criticisms of the EU, the ADR nuanced its positions on many points. The ADR made it clear that it supported the EU. It noted the great advances the EU had given to Europe in terms of peace and prosperity in post-war Europe (ADR, 2024a: 3). The party was thus concerned that so many people had lost their trust in the project and stated that their goal was ‘to stabilize Europe in these times and rebuild it at the same time so that the idea of a European Union remains attractive for the next generations in as many countries as possible’ (ADR, 2024a: 2). On these points, the ADR made a clear distinction between itself and other right-wing populist parties. As Alexandra Schoos, president of the ADR at the time of the EU election, stated in an interview: “The intention of the ADR is certainly not to destroy the European project from within. As Luxembourg, we need Europe and a European Union. The ADR is therefore certainly not on the same line as defended by certain parties which are opposed to the EU” (Schoos, 2024).

The ADR similarly struck a positive tone on the issue of migration (or at least legal migration within EU borders, of which there is a great deal in Luxembourg): ‘The ADR is expressly of the opinion that the legal migration of persons in the internal market can bring many advantages and should continue to be encouraged’ (ADR, 2024a, pp. 3–4). These nuances were also visible in the ADR’s campaign posters, which also served as social media posts. The image in Figure 1 from the party’s Facebook page states, ‘Don’t ban the combustion engine’ Below the image is the ADR’s EU campaign slogan: Fir e staarkt Lëtzebuerg an Europa (‘For a strong Luxembourg in Europe’). This slogan clearly indicated that the ADR saw Luxembourg’s destiny as closely tied to that of the EU.

These nuanced positions are consistent with the brand of right-wing populism the ADR embodies, which offers moderate critiques of the EU, all while distancing itself from the more radical positions taken by other European right-wing populist parties (Carls, 2023).

The ADR performed its message in a variety of ways. Party leaders such as Fernand Kartheiser, Fred Keup, and Alexandra Schoos made media appearances for interviews or debates with other candidates in national print newspapers, on national radio stations such as Radio Television Luxembourg (RTL) or Radio 100.7, and on TV, for example, on RTL’s Kloertext or Table Ronde programs. The party was also active on social media, posting content on Facebook, X, Instagram and TikTok. ADR candidates and party representatives were also present at stands at local street markets and events throughout the country in the weeks and months leading up to the election.

Election results: The demand side

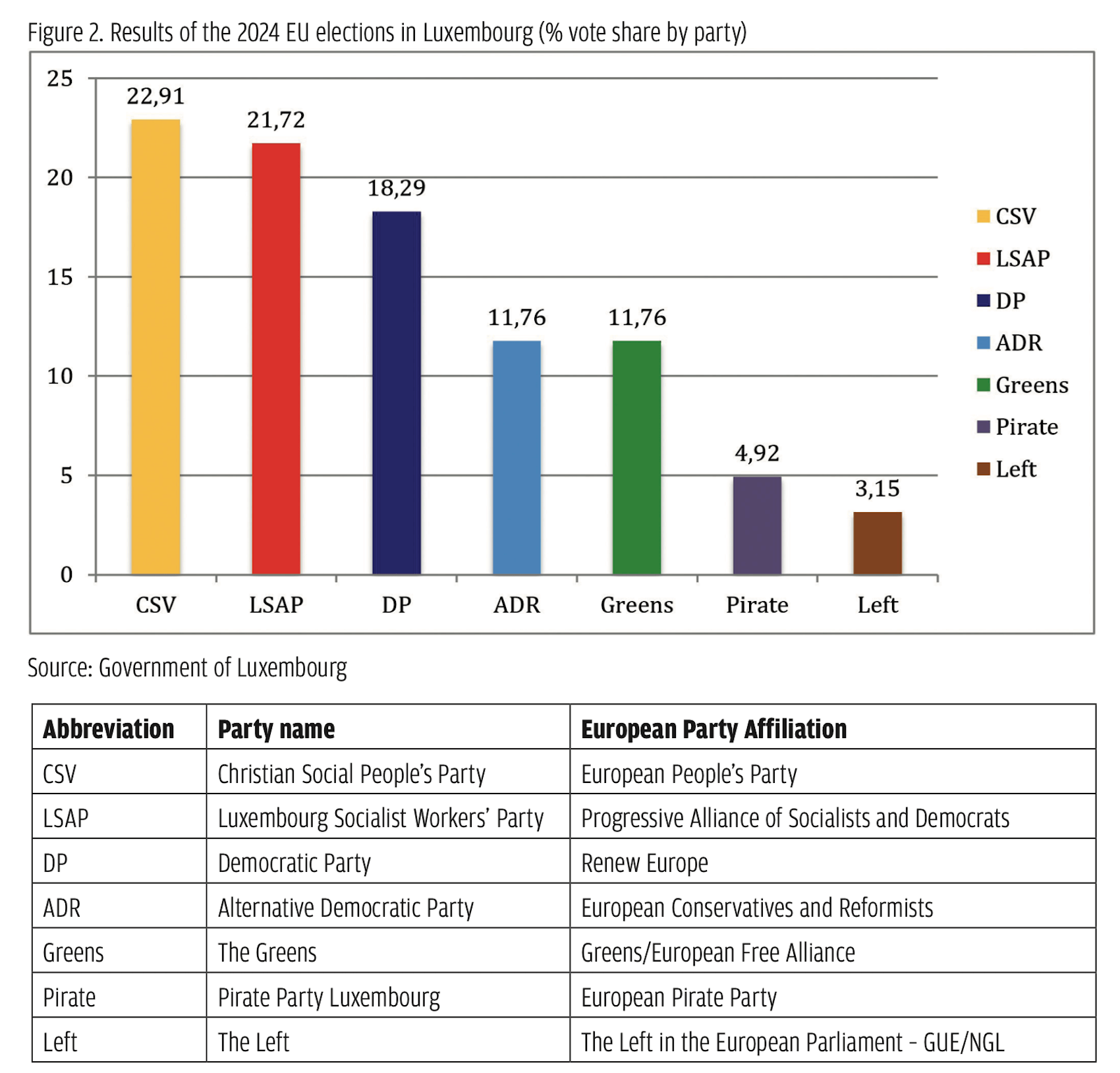

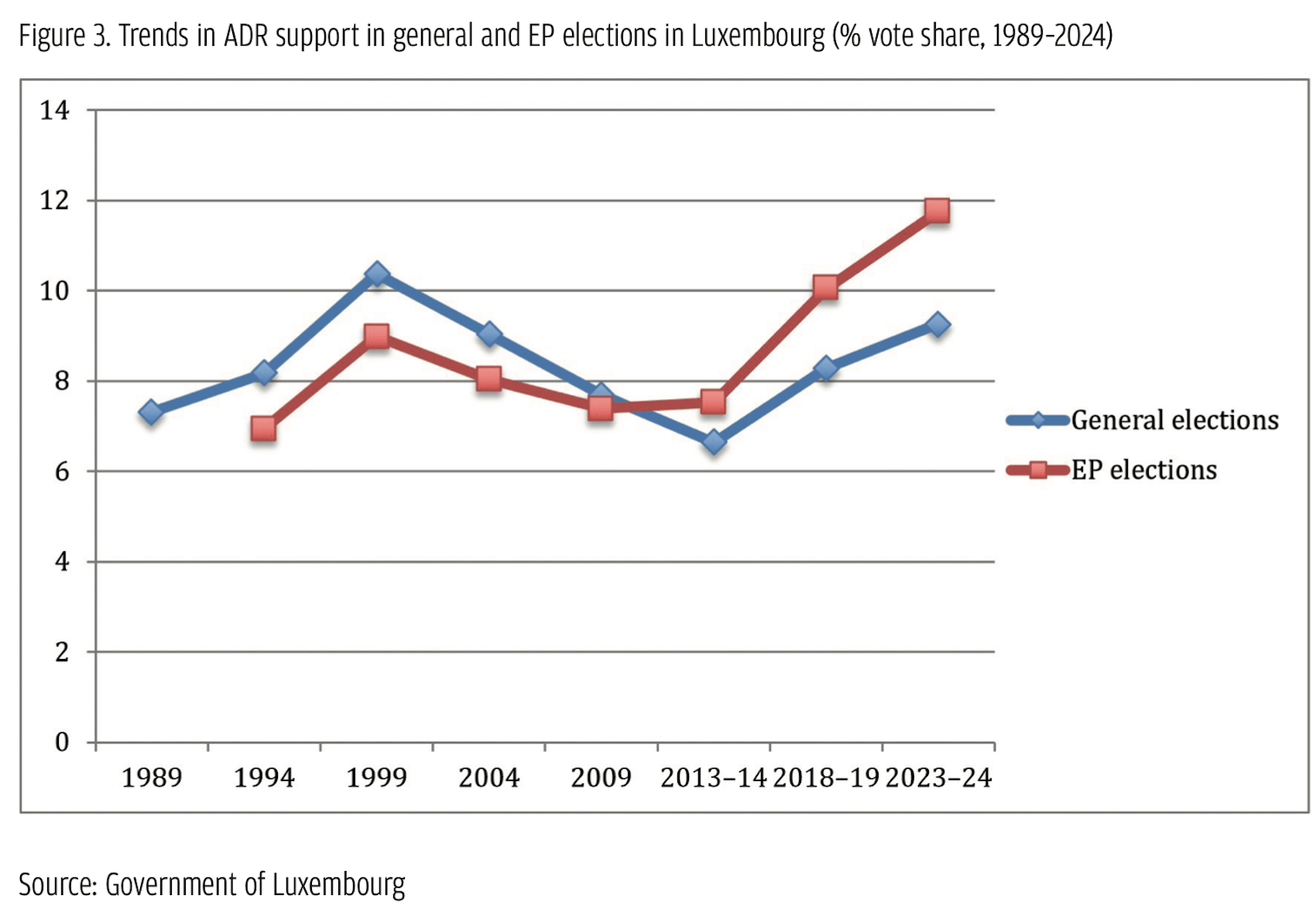

The election results can be found in Figure 2. The Christian Social People’s Party (CSV), a member of the European People’s Party (EPP) group, came in first with 22.91% of the vote and obtained two EP seats. The ADR tied with the Greens at 11.76%, an improvement of 1.72 percentage points over their showing in 2019 and also higher than their performance in the 2023 general election, allowing them to obtain their first-ever EP seat, which was filled by Fernand Kartheiser. All remaining elected parties received one seat in the EP. All the main issues the ADR campaigned on likely contributed to their success, with none standing out. Figure 3 shows the trends in the ADR’s electoral support since its founding and shows that this support has grown only marginally since 1989. While there was talk of a Rechtsruck or strong shift to the right in many European countries, it would be wrong to claim this was the case in Luxembourg. Support for the ADR has remained relatively steady between 8–10% over the decades, and while the 2024 EP election result was the party’s highest showing yet, the party remains a relevant but junior player in Luxembourgish politics. Nevertheless, the result allowed the ADR, for the first time, to be represented at all levels of government in Luxembourg and marked a high point in the party’s history.

The media landscape of Luxembourg is quite distinctive. Print publications receive generous state subsidies to preserve media plurality and many such publications have a direct link to established political parties. The largest and oldest newspaper, the Luxemburger Wort, has connections to the CSV, while the second largest, the Tageblatt, has connections to the Luxembourg Socialist Workers’ Party (LSAP). The country is also very small, leading to a high degree of familiarity between journalists and political actors. As a result, the media landscape generally reflects the moderate views of the country’s political elites (de Jonge, 2021, pp. 159–163). That said, the print mostly reported on the election results in a mostly neutral way, simply noting the results and that it was a historic night for the ADR. Such was the case with the article in the Luxemburger Wort, which also included quotes from many ADR politicians (Javel, 2024). One exception came from the Tageblatt, which noted in their coverage that the ADR was among the ranks of ‘right-wing populists’ (Rechtspopulisten). The article also noted that the ADR would caucus with the ECR, which was led by the ‘post-fascist’ Giorgia Meloni and would likely soon include Hungary’s Fidesz party, whose leader Viktor Orbán was an ‘outspoken friend’ of Vladimir Putin (Kemp, 2024). Apart from such exceptions, print media reporting on the ADR leading up to the election was also mostly neutral.

The situation was similar regarding radio and television leading up to the election, with coverage mostly neutral and the ADR being invited, as with all other parties, to debates, interviews and other events hosted by, for example, RTL, the country’s main radio and television station. Unlike in other countries where there is a Brandmauer (firewall) or cordon sanitaire surrounding right-wing populists, no such impediments to presenting their positions on a general media platform existed for the ADR during the election.

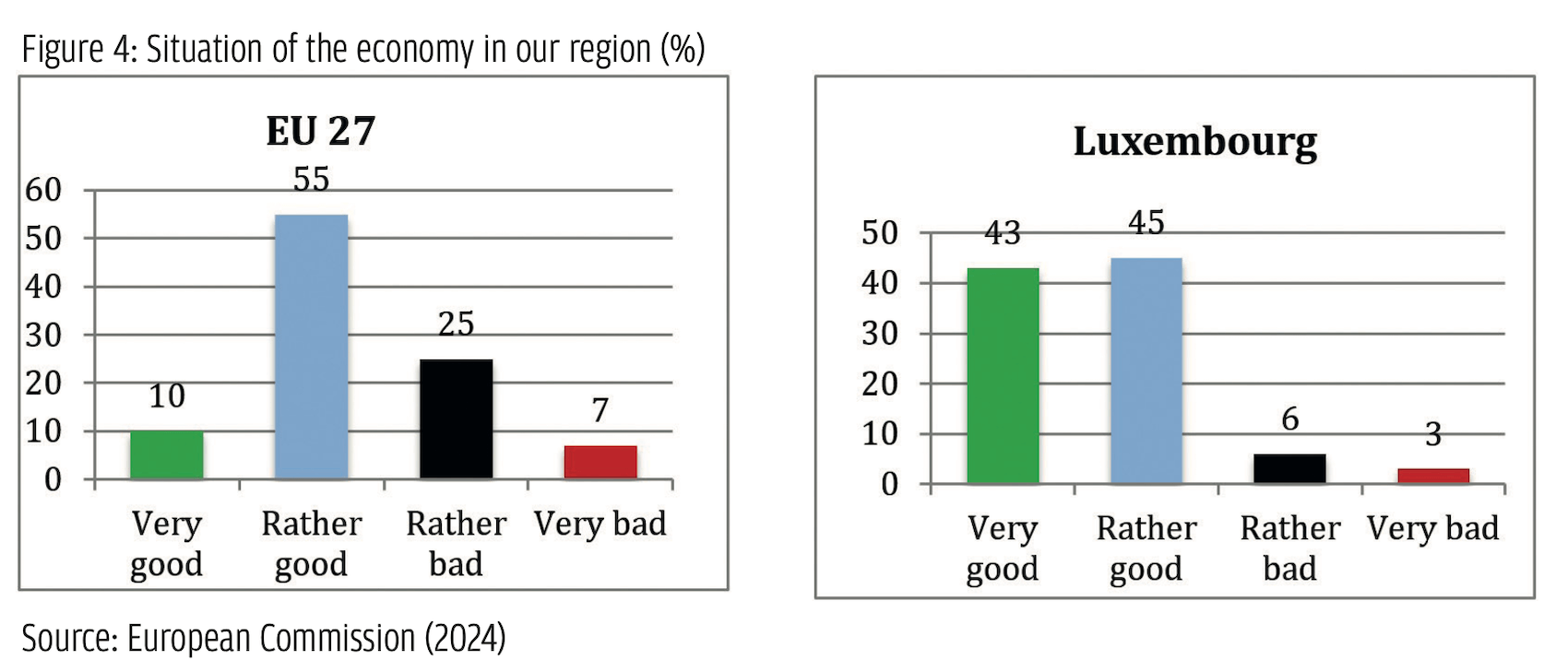

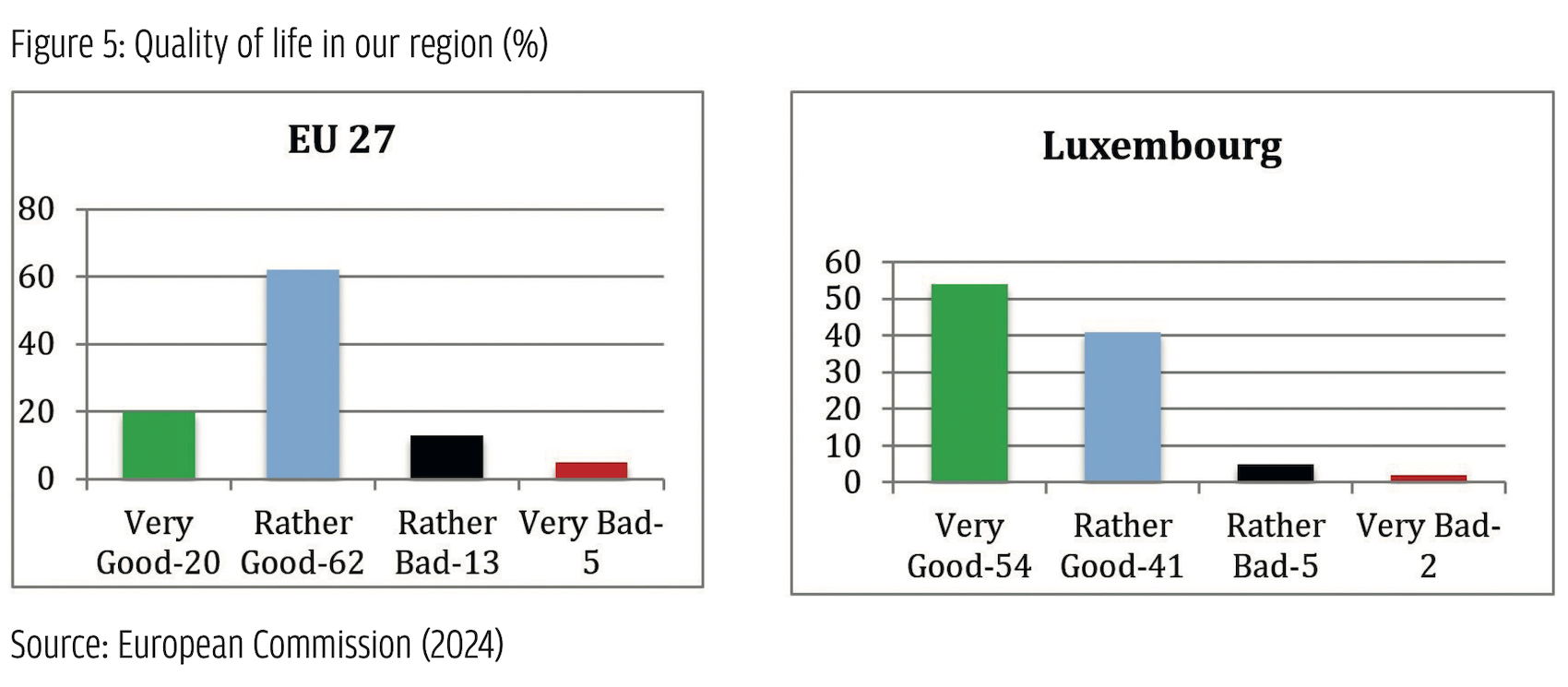

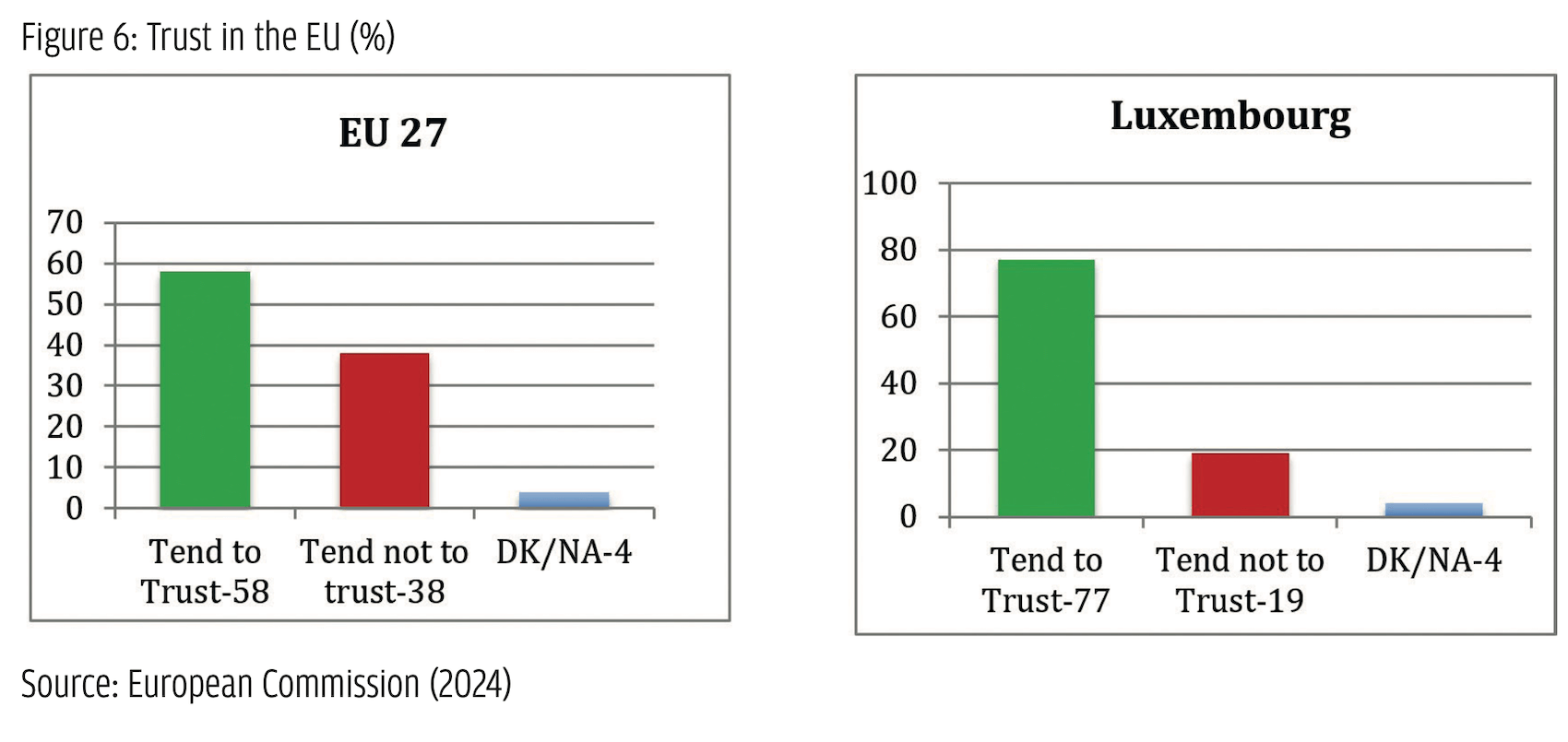

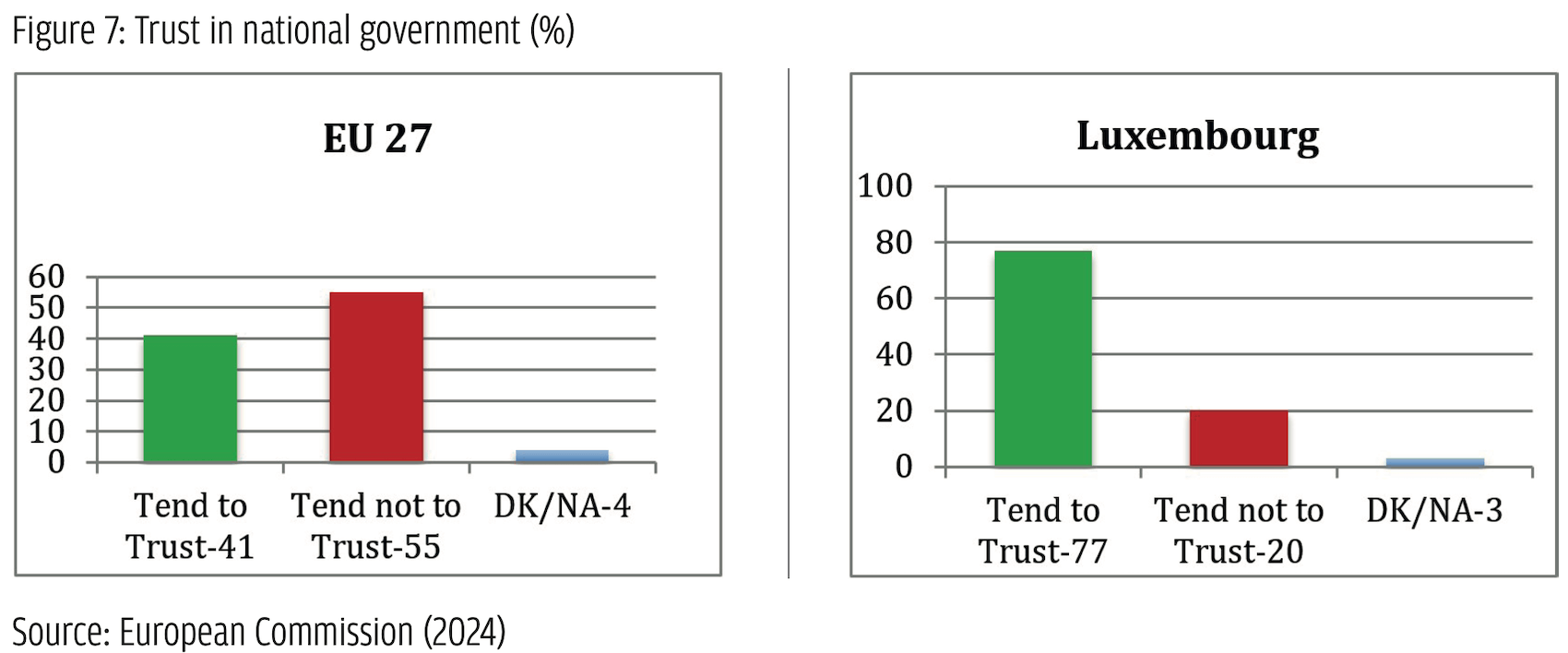

While there exists no exit-poll data with which to analyse the election results, a Eurobarometer report from the winter of 2024 by the European Commission (2024) sheds light on the particularities of Luxembourg that contributed to the success or lack thereof of the ADR. The report looks at Luxembourgers’ views on topics such as the EU and their economic situation, and it shows that compared to the EU average, Luxembourgers were far more satisfied with their economic situation and the EU.

As Figures 4, 5, 6 and 7 demonstrate, those living in Luxembourg felt much better off economically and also had much higher levels of trust in their national government and the EU. These are generally indicators of success for right-wing populist parties and populist parties in general. That Luxembourg had strongly divergent responses compared to the EU 27 indicates the lack of demand for a right-wing populist party that is aggressively anti-EU or anti-immigration. These poll results also show the limited demand for a party like the ADR, which nuanced its criticisms of the EU with praise but also presented itself as an ‘outsider’ to the political establishment.

Discussion and perspectives

An aggressive or radical right-wing populist party seen in other European countries is not electorally viable in Luxembourg, a well-off, highly international and economically interconnected country. As a result, the ADR modulates its discourse to appeal to a population that is largely optimistic about its general economic situation and its place within the EU (see also Carls, 2023). For this reason, it represents a more moderate form of right-wing populism and will likely be among the most moderate and pragmatic members of the ECR group in the EP.

In the EP, the ADR will likely prioritize the core issues it campaigned on: maintaining the right of veto on the European Council, opposition to federalist tendencies in the EU, opposition to the Green New Deal, a politics of peace in the Ukraine war, defending free speech and finding a solution to the migration crisis. In this respect, the ADR will not be much different than most other right-wing populist parties in Europe, especially those within the ECR. What will distinguish the ADR is its advocacy for the Luxembourgish language. Luxembourgish holds a special place in Luxembourgish politics not only as a cultural marker of national identity but also because C1 level (basically native fluency) is a requirement for almost all public sector jobs. These jobs are extremely well paid and ensure many Luxembourgers a good standard of living. Abolishing this requirement would remove Luxembourgers’ special access to this range of jobs (Carls, 2023). Having Luxembourgish recognized as an official European language in the EU would solidify its status in Luxembourg. This issue will likely be a top priority of Fernand Kartheiser.

Ultimately, political parties represent the views of those who support them. In Luxembourg there is little appetite for a right-wing populist party that is aggressively anti-immigration or anti-EU. Quite simply, the country benefits too much from these aspects of European integration. Looking at trends in the EU more widely, Luxembourg seems quite exceptional in this sense. It is therefore difficult to extrapolate any recommendations or generalities from the Luxembourgish case.

(*) Paul Carls holds a PhD in political science from the Université de Montréal and completed a post-doctoral research assistantship at the Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER). He has published on the topics of multiculturalism and right-wing populism in Germany, Luxembourg and France.

References

ADR (2022). Ukrain. https://adr.lu/ukrain/

ADR (2023). ADR-Walprogramm fir d’Chamberwalen, den 8.Oktobe 2023.

ADR (2024a). Fir e staarkt Lëtzebuerg an Europa Walprogramm fir d’Europawalen 2024.

ADR (2024b, 1 June). De Verbrennungsmotor net ofschafen. Facebook https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=874381084714804&set=a.301892138630371

Blau, L. (2005). Histoire de l’extrême-droite au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg au XXe siècle. 2nd edition. Le Phare.

Camus, J. (2017). Extremismusforscher Jean-Yves Camus: ‘Die ADR ist nicht rechtspopulistisch’. Luxembuger Wort. 29 January: https://wort.lu/de/politik/extremismusforscher-jean-yves-camus-die-adr-ist-nichtrechtspopulistisch-588e44c7a5e74263e13a9c53

Carls, P. (2023). Approaching right-wing populism in a context of transnational economic integration: Lessons from Luxembourg. European Politics and Society 24(2): 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2021.1993056

De Cleen, B. (2017). Populism and Nationalism. In C. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism (pp. 342–362), Oxford University Press

De Jonge, L. (2021). The Success and Failure of Right-wing Populist Parties in the Benelux Countries. Routledge

European Commission (2024) Flash Eurobarometer: Public opinion in the EU region, Luxembourg. European Union.

Fetzer, J. (2011). Luxembourg as an Immigration Success Story: The Grand Duchy in Pan-European Perspective. Lexington Books.

Kemp, G. (2024). ‘Glücklose Gewinner, zufriedene Verlierer’, Tageblatt, 10 June: https://www.tageblatt.lu/headlines/gluecklose-gewinner-zufriedene-verlierer/

Javel, F. (2024). ‘ADR sichert sich zum ersten Mal Sitz im EUParlament’, Luxemburger Wort, 9 June: https://www.wort.lu/politik/adr-sichert-sich-zum-ersten-mal-sitz-im-eu-parlament/13746916.html

Lamour, C. and P. Carls (2022). When COVID-19 circulates in right-wing populist discourse: The contribution of a global crisis to European meta-populism at the cross-border regional scale. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, pre-print: https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2022.2051001

Mudde, C. (ed.). (2017b). The Populist Radical Right. Routledge.

Poirier, P. (2012). L’ADR: de la recherche de l’équité à la construction inachevée d’un mouvement conservateur et souverainiste. https://adr.lu/ladr-de-la-recherche-de-lequite-a-la-construction-inachevee-dun-mouvement-conservateur-et-souverainiste/

Rydgren, J. (2007). The Sociology of the Radical Right. Annual Review of Sociology vol. 33: 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752

Schoos, A. (2024) Alexandra Schoos: Notre intention n’est pas de détruire le projet européen. Le Quotidien. 30 May. https://lequotidien.lu/a-la-une/elections-europeennes-alexandra-schoos%E2%80%89-notre-intention-nest-pas-de-detruire-le-projet-europeen/

Schulze, I. (2006). Luxembourg: an electoral system with panache. In E. Immergut, K. Anderson, & I. Schulze (eds.), The Handbook of West European Pension Politics (pp. 804–853). Oxford University Press.

STATEC. (2020). Population Structure. https://statistiques.public.lu/stat/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=12853&IF_Language=eng&MainTheme=2&FldrName=1

Taguieff, P. (2015). La revanche du nationalism: Néopopulistes et xenophobes à l’assaut de l’Europe. Presses Universitaires de Frane.

Zulianello, M. (2020). Varieties of Populist Parties and Party Systems in Europe: From State-of-the-Art to the Application of a Novel Classification Scheme to 66 Parties in 33 Countries. Government and Opposition 55: 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2019.21