Please cite as:

ECPS Staff (2026). “ECPS Panel at European Parliament: Populism, Trump, and Changing Transatlantic Relations.” European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS). February 11, 2026. https://doi.org/10.55271/rp00143

The ECPS panel held at the European Parliament on 3 February 2026 marked a critical intervention into debates on the future of transatlantic relations amid the resurgence of right-wing populism in the United States. Convened to launch the report “Populism and the Future of Transatlantic Relations: Challenges and Policy Options,” the event brought together policymakers, scholars, and civil society actors to assess how Donald Trump’s re-election has reshaped Europe’s strategic environment. Discussions highlighted the simultaneous erosion of security cooperation, trade norms, multilateral institutions, and shared democratic values. Rather than treating these developments as temporary disruptions, the panel framed them as structural challenges requiring European agency, strategic autonomy, and democratic resilience. The report positions Europe not as a passive responder, but as a decisive actor capable of shaping a post-assumptive transatlantic order.

Reported by ECPS Staff

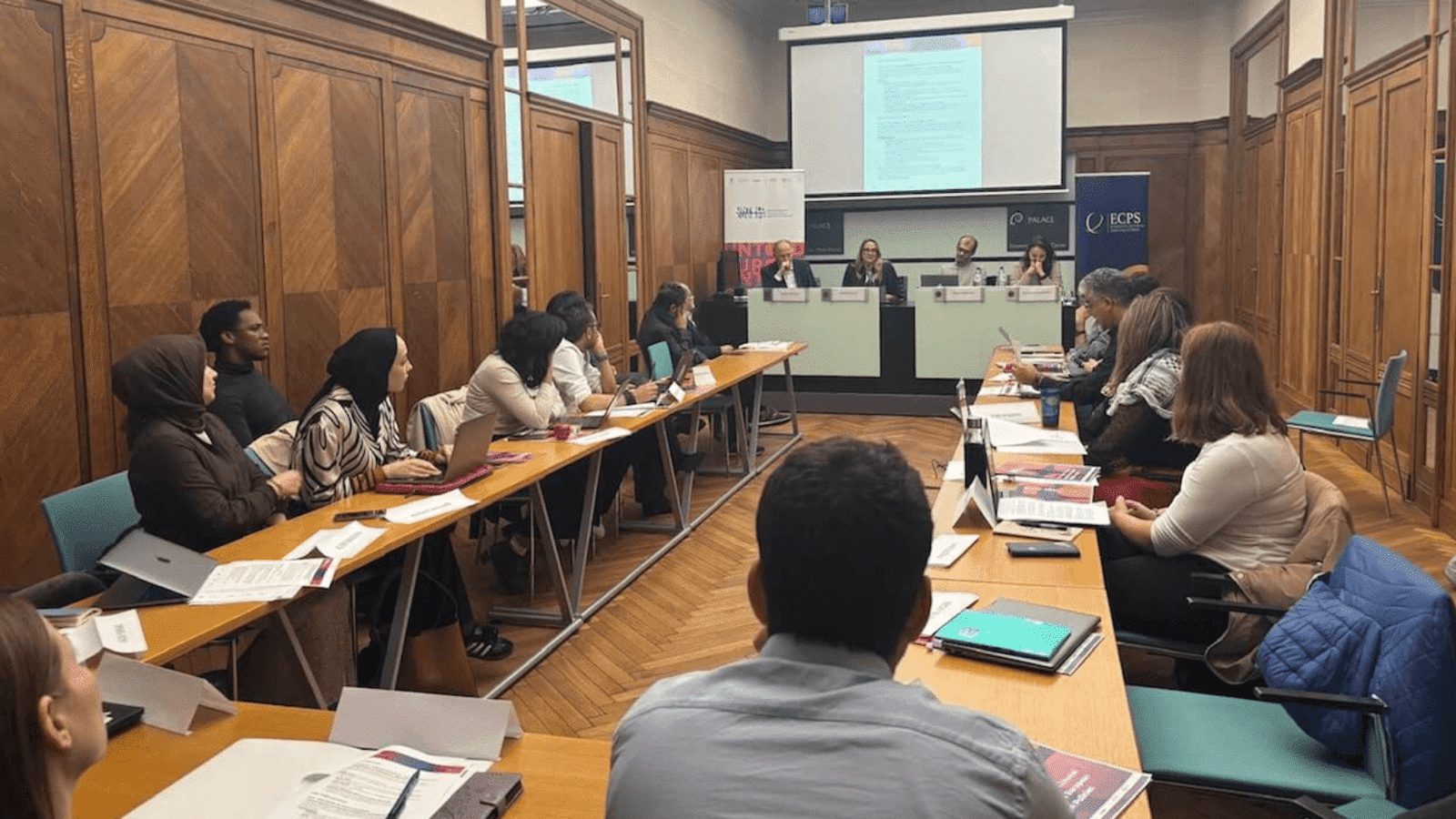

On 3 February 2026, the European Parliament hosted an ECPS panel convened to launch the report Populism and the Future of Transatlantic Relations: Challenges and Policy Options, a timely intervention into the accelerating strain on the post-war Atlantic order. Held in the Spinelli building in Brussels and hosted by MEP Radan Kanev, the event assembled Members of the European Parliament, scholars, policy practitioners, journalists, and civil society observers around a shared concern: the extent to which renewed US right-wing populism—crystallized in Donald Trump’s re-election in 2024—has shifted the premises of Europe’s external environment and, increasingly, its internal political equilibrium.

The discussion proceeded from the report’s core proposition that transatlantic relations cannot be understood only as a matter of diplomacy or foreign policy. Rather, domestic political dynamics—polarization, institutional capture, disinformation, and the reconfiguration of party systems—now shape the external posture of states and alliances. Against this backdrop, the panel examined how pressures on the four foundational pillars of the liberal international order—security cooperation, free trade, international institutions, and shared democratic values—are unfolding simultaneously and interactively. The report, coordinated under the ECPS and produced through a transatlantic academic collaboration involving the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign, UC Berkeley, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and ARENA at the University of Oslo, offers a structured assessment of these developments and outlines policy options aimed at risk reduction and strategic adaptation.

Co-moderated by ECPS Honorary President Irina von Wiese and former MEP Sir Graham Watson, the event opened with reflections that framed the moment as one of geopolitical reordering and democratic vulnerability. Von Wiese situated Europe’s predicament within a wider shift in power relations, while Sir Watson emphasized the immediacy of populist mobilization and the need for democratic coordination beyond Europe. MEP Kanev’s hosting remarks foregrounded the entanglement of European domestic politics with US leadership change and warned of new forms of external meddling in Europe’s internal affairs. Further political interventions by MEP Valérie Hayer (The Chair of the Renew Europe Group) and MEP Brando Benifei (Chair of the EP Delegation for relations with the United States) underscored the ideological nature of Trumpism’s challenge to “liberal Europe,” the necessity of European firmness and credibility, and the growing imperative of strategic autonomy across trade, technology, and security.

The report’s editors—Marianne Riddervold, Guri Rosén, and Jessica Greenberg—then presented the report’s analytical architecture and central findings, before a wide-ranging Q&A tested its implications against questions of narrative, coalition-building, European divisions, and the operationalization of democratic resilience. Collectively, the panel framed the report not as a lament for a weakening alliance, but as a call to clarify Europe’s agency under uncertainty—and to translate unity, leverage, and values into durable policy choices.

Irina von Wiese: Opening Reflections on Populism and a Changing Geopolitical Order

In her opening remarks as co-moderator of the panel, ECPS Honorary President Irina von Wiese set an reflective tone, situating the discussion of populism, Donald Trump, and changing transatlantic relations within both institutional and geopolitical contexts. Von Wiese noted that the report under discussion had been initiated well before its public launch, remarking on the striking extent to which unfolding global developments had amplified its relevance. She suggested that the themes addressed would likely remain salient for the foreseeable future, given the enduring transformations underway in global politics.

Drawing on a personal yet analytically resonant observation from her vantage point in central London, von Wiese referred to the construction of the new Chinese “super embassy” as a symbolic marker of broader geopolitical shifts. This development, she argued, encapsulated the pressures facing Europe as it navigates a rapidly evolving international order characterized by intensifying competition between emerging and established superpowers. Without pre-empting the panel’s substantive debates, she framed Europe’s position as increasingly constrained, compelled to recalibrate its strategic choices amid rival spheres of influence.

Concluding her remarks, von Wiese emphasized the importance of dialogue and multidisciplinary engagement, before inviting MEP Kanev to proceed and introducing Sir Graham Watson, her predecessor as Honorary Chair of ECPS, as a special guest.

Sir Graham Watson: Europe’s Populist Moment and the Imperative of Democratic Unity

In his opening remarks, Sir Graham Watson, founding honorary president of the ECPS, adopted a deliberately concise and candid tone. Sir Watson expressed strong appreciation for the participation of Valerie Heyer and Radan Kanev, emphasizing that their support for the report had been exemplary. He underlined their importance as political actors actively resisting the advance of populism within Europe, describing such engagement as both timely and essential.

He then drew attention to the immediacy of the populist challenge by noting that, at that very moment, a gathering of European populist actors was taking place nearby. Sir Watson warned that these movements were seeking to replicate in Europe the political dynamics associated with Donald Trump in the United States. Countering this trend, he argued, required firm and value-based cooperation with democratic partners committed to the rule of law and structured multilateral engagement, specifically referencing countries such as Canada and South Korea.

Sir Watson further criticized what he described as incoherence in European trade policy, pointing to the inconsistency of rejecting an unfair trade agreement with the United States while subsequently referring the Mercosur agreement to the Court of Justice. He stressed the need for Europe to “de-risk” its relations with populist-led governments, proposing closer engagement with democratic governments in countries such as Brazil and Argentina.

Sir Watson clarified that while these broader issues framed the discussion, the report itself offered a more focused analysis of the populist challenge and concrete guidance for policymakers, which he warmly commended to the audience.

Openning Remarks by MEP Radan Kanev: “The Importance of Re-evaluating Transatlantic Relations in the Current Global Political Climate”

In his opening remarks as host of the event, MEP Radan Kanev emphasized both the timeliness and the political significance of the discussion, expressing sincere appreciation for the opportunity to host what he described as an extremely important initiative. He thanked fellow Members of the European Parliament, including Valerie Hayer and Brando Benifei, for their participation, highlighting their presence as evidence of the cross-party character of the meeting and of a shared concern that transcended partisan boundaries.

Kanev opened substantively by citing the very first premise of the report being launched: that, under current conditions, domestic politics may matter more than foreign policy. He expanded this proposition by arguing that what is at stake is not merely domestic politics in general, but specifically Europe’s internal political dynamics and their growing entanglement with leadership developments in the United States. To illustrate this point, he turned to the political situation in his home country of Bulgaria, describing a striking competition among three prominent political figures—an influential oligarch, a long-standing dominant political leader, and a recently resigned president-turned-political actor—each openly vying for the favor of Donald Trump.

This dynamic, Kanev suggested, had reached an unprecedented point with the decision of Bulgaria’s already resigned pro-European prime minister to sign the so-called “Charter of the Board of Peace,” making Bulgaria—alongside Hungary—the only representatives of the European Union to do so. He underscored the paradox of this situation, noting that one of the signatories belonged to the European People’s Party (EPP) rather than to the political families typically associated with extremist or openly anti-European positions.

Kanev stressed that populism alone did not sufficiently explain the gravity of the current moment. Drawing on his own long political experience, he observed that Bulgaria, like many European countries, had been governed by various forms of populism—left-wing, right-wing, and centrist—for decades. The rise of populist movements, he argued, was therefore not in itself a novel or alarming development, nor an inevitable cause for panic. What Europe was facing, however, was something more profound and more destabilizing than the circulation of populist rhetoric.

To clarify this distinction, Kanev urged the audience to acknowledge several uncomfortable but necessary truths. From a European perspective, he argued, every Republican US president could historically be perceived as a form of right-wing populist, and indeed every American president since Andrew Jackson could be seen as populist to some degree. Moreover, US foreign policy had long been difficult for Europeans to accept, well before the Iraq War of 2003. Yet, Kanev insisted, Donald Trump represented a qualitatively different phenomenon.

This difference, he argued, could not be reduced simply to right-wing populism, domestic authoritarian tendencies, or aggressive rhetoric abroad—traits that many Europeans had, rightly or wrongly, long associated with US leadership. European leaders, Kanev suggested, might have been willing to tolerate Trump’s domestic agenda, despite its damaging effects on American institutions, and even his confrontational, transactional style in transatlantic relations, as evidenced by recent trade and security negotiations.

What fundamentally distinguished the present situation, in Kanev’s view, was the unprecedented level of direct meddling in Europe’s internal political affairs. Historically, while the United States had supported authoritarian or unsavory regimes elsewhere, it had never done so in Europe. On the contrary, US policy had consistently promoted democracy, market economies, free trade, and, crucially, European integration. Kanev emphasized that Bulgaria’s own accession to the European Union had been made possible largely through strong US pressure, a fact well known both in Western Europe and in the Balkans.

This longstanding pattern, he argued, had now been reversed. The current US administration, Kanev maintained, was actively working toward European disunity, seeking to transform Europe into an insecure and fragmented space of competing client projects—an approach previously seen in other regions of the world, but never within Europe or the transatlantic partnership. He cautioned against overemphasizing ideology or values in explaining this shift, suggesting instead that many European leaders aligning themselves with Trumpist positions were motivated less by genuine conservatism or nationalism than by personal authoritarian ambitions or corruption.

Kanev concluded by stressing that the challenges identified in the report—particularly in the areas of security and trade—were not confined to Brussels but affected national and pan-European levels alike, extending even beyond the EU to partners such as Norway, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Addressing Europe’s right-wing nationalist and conservative movements directly, he posed a series of rhetorical questions to underline the contradictions inherent in their current alignments. He argued that the emerging political cleavage in Europe would no longer be defined by traditional ideological labels, but by a stark choice between accepting Europe as a chaotic sphere of multiple foreign influences or defending European solidarity as a matter of fundamental security and prosperity.

MEP Valérie Hayer: “Reflections on the Implications of Renewed US Populism for European Policies, Democratic Values, and Foreign Relations”

In her address, Valérie Hayer, Chair of the Renew Europe Group in the European Parliament, situated the discussion of renewed US populism within a broader transatlantic and democratic framework. Opening with expressions of gratitude to the organizers and contributors to the report, she emphasized both the importance and urgency of the initiative. She extended particular thanks to Radan Kanev for the invitation, noting that her remarks were shaped by her recent visit to Bulgaria, where she had met with civil society actors, journalists, advocates of judicial independence, and public authorities.

Drawing on this experience, Hayer pointed to the role of entrenched oligarchic power in undermining the rule of law, arguing that such dynamics posed threats comparable to, or even exceeding, those posed by the current US administration within its own institutional context. This observation served as an entry point into her central argument: that attacks on democracy are intensifying globally, including in the United States, long regarded as a bastion of freedom. The return of populism to the center of American power, she stressed, constituted not merely a domestic political development but a transatlantic shockwave with direct implications for European policies, democratic resilience, and Europe’s global position.

Hayer framed her intervention around three interrelated questions: what US populism means for Europe, how it operates, and how Europeans must respond. She argued that understanding these implications required conceptual clarity about Trumpism itself. While Donald Trump’s initial election in 2016 had often been interpreted in Europe as an anomaly driven by protest voting and institutional fatigue, his return to power in 2024 decisively shattered this assumption. Rather than an accident, it represented confirmation that Trumpism had evolved into a consolidated and ideologically coherent movement exercising near-total control over the Republican Party. Populism in the United States, she argued, had proven structural and resilient, capable of returning even after electoral defeat.

Trumpism Does Not Oppose Europe Per Se; It Opposes Liberal Europe

A central clarification in Hayer’s analysis concerned the object of Trumpism’s hostility. The Trumpist movement, she contended, is not directed against Europe as a civilization or geographical entity, but against liberals, moderates, pluralists, and defenders of democratic norms wherever they are found. In this sense, Trumpism does not oppose Europe per se; it opposes liberal Europe. This distinction explained why Trump and his allies often appeared ideologically closer to European far-right parties than to large segments of their own domestic electorate. Hayer noted that Trumpism displayed greater affinity with parties such as Germany’s AfD or France’s National Rally than with US Democrats or moderate Republicans, a pattern reflected in Trump’s hostility toward liberal European leaders and his praise for illiberal ones.

This ideological divide, she argued, was starkly exposed by the events of January 6, 2021. The assault on the US Capitol was not simply a security failure but a test of democratic allegiance. Those who unequivocally condemned it affirmed their commitment to liberal democracy, while those who minimized or justified it revealed a different set of priorities. Trump’s subsequent return to power sent a powerful signal to populist actors worldwide: violations of democratic norms could be politically survivable. This message, Hayer warned, emboldened illiberal movements in Europe as much as in the United States.

She further argued that the first norm eroded by Trumpism was truth itself. Trump’s governance, she observed, was marked by apparent contradictions: claims to uphold law and order while attacking judges and prosecutors; rhetorical support for democratic protesters abroad while repressing dissent at home; denunciations of corruption alongside the rewarding of personal loyalty over legality. These were not inconsistencies, she maintained, but defining features of transactional populism, in which loyalty and expediency outweigh institutions and rules. Such an approach destabilizes alliances by replacing predictability with improvisation and shared values with ad hoc deals.

This logic, Hayer argued, extended directly into foreign policy. Trump’s hostility toward the European Union was not merely economic or strategic, but ideological. The EU embodies regulation, multilateralism, minority protection, climate governance, and judicial independence—precisely the elements Trumpism frames as illegitimate liberal overreach. Consequently, EU laws are portrayed as constraints, European unity as a threat, and even territories such as Greenland as negotiable assets. In this worldview, European leaders are divided not by nationality but by ideology—classified as allies or adversaries depending on their stance toward liberal democracy.

Faced with this reality, Hayer called for a strategic, rather than emotional, European response. Europeans cannot determine US electoral outcomes, she acknowledged, but they retain agency in shaping their own reactions. She cited recent European initiatives—the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, the Digital Services Act, and the Digital Markets Act—as examples of necessary assertions of sovereignty in a hostile global environment. At the same time, she identified a major European failure: complacency following the election of Joe Biden, which led many to assume that Trumpism had been definitively defeated.

This misjudgment, she argued, contributed to delayed investments in European autonomy and resilience, particularly in defense, financial integration, and industrial capacity. She emphasized that the current US administration responds primarily to leverage rather than goodwill. When Europe demonstrated resolve—through trade instruments, deterrence signals, or legal firmness—the tone of engagement shifted. When it hesitated or sought appeasement, pressure intensified. The episode surrounding Greenland illustrated the necessity of firmness, not escalation, but credible dissuasion grounded in clear red lines.

Hayer concluded that European independence is no longer optional. Dependence creates vulnerability, whereas strategic autonomy enables resilience. She stressed that Europe possesses substantial industrial, technological, and economic assets, naming key actors across defense, energy, and technology sectors. Europe’s weakness, she argued, lies not in a lack of resources but in fragmentation, underinvestment, and political hesitation.

The decisive battleground, however, remains internal. While Europe cannot prevent populism in the United States, it can prevent it from governing Europe. Hayer warned against European populist leaders who align themselves ideologically with Trumpism, describing them as conduits rather than defenders of European sovereignty. Trumpism, she concluded, is not an external imposition but a project that survives in Europe only if Europeans legitimize it. The ultimate question, therefore, is not whether populism exists, but whether Europeans allow it to rule them.

MEP Brando Benifei: Taking Europe Seriously in an Era of Populism and Uncertainty

In his address, MEP Brando Benifei, Chair of the European Parliament’s Delegation for Relations with the United States, offered a practitioner-oriented reflection on the state and future of transatlantic relations, grounded in his direct and ongoing engagement with US counterparts. Benifei expressed particular gratitude to Radan Kanev and Valérie Hayer for convening the meeting in cooperation with the ECPS, emphasizing the importance and timeliness of the report being launched. He briefly previewed the report’s analytical framework, noting that it focused on four core pillars currently under strain: security, trade, international institutions, and democratic values. These themes, he suggested, captured the multidimensional nature of the present challenges, which would be explored in greater depth by the report’s authors.

Drawing on his role as chair of the transatlantic delegation, Benifei underlined the value of sustained dialogue with US political actors, highlighting both his frequent visits to the United States and the presence of representatives from American think tanks in the audience. He described the European Parliament as a “House of Democracy” and welcomed the opportunity for open exchange within this institutional setting.

Turning to the substance of the report, Benifei referred to the three scenarios it outlines for the future of transatlantic relations: potential disintegration, functional adaptation, or reorganization on new foundations. Based on his recent experiences with US administration officials, members of Congress, and other stakeholders, he argued that all three scenarios remained plausible in the current complex context. He emphasized, however, a central lesson drawn from these interactions: the European Union must be taken seriously. This requires clarity of position, internal unity, and—crucially—consistency between declarations and actions.

Benifei warned that recent patterns of announcing positions and subsequently retracting or failing to implement them had undermined the EU’s credibility in the eyes of US interlocutors. While he shared the view, often expressed by members of the US Congress, that Europeans should not overreact to daily rhetoric or shifting statements, he stressed that words had, at times, translated into concrete actions requiring firm responses.

In this context, he echoed the importance of European legislative sovereignty, particularly in relation to digital regulation. Referring to the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act, Benifei expressed concern that US counterparts had explicitly urged changes to these laws in formal meetings. He rejected this approach, arguing that Europe must stand firm in defending its regulatory choices.

In concluding, Benifei argued that confronting populism and redefining transatlantic relations requires clarity about Europe’s own political project. Citing remarks by Mario Draghi delivered the previous day, he endorsed the view that the era of the EU as a loose confederation had ended. In a relationship increasingly shaped by political and security considerations, rather than commerce alone, Europe must strengthen its sovereignty and internal organization if it wishes to engage the United States on a more equal footing. The report, he concluded, offers a valuable contribution to understanding both Europe’s current position and the strategic paths ahead.

Professor Marianne Riddervold: The Four Pillars of the Atlantic Order Under Strain

In her presentation as one of the three editors of the ECPS report, Professor Marianne Riddervold, affiliated with ARENA at the University of Oslo, NUPI, and the University of California, Berkeley, introduced the report’s core analytical framework and key findings concerning the evolving state of transatlantic relations under renewed US right-wing populism.

Professor Riddervold grounded the report’s intellectual motivation in an observation made as early as 2018 by John Peterson, who argued that the future of US–European relations and the liberal international order depended less on foreign policy choices than on domestic democratic politics in both Europe and the United States. In light of Donald Trump’s reelection in 2024, she suggested that this assessment had proven prescient. Contemporary news coverage, she noted, is dominated by developments that appear to challenge the very foundations of the transatlantic relationship, including disputes over tariffs, divergent approaches to Ukraine, tensions surrounding international treaties and voting behavior in the United Nations, uncertainty about NATO’s future, and deep disagreements over free speech norms. These tensions have been further exacerbated by Trump’s public threats to annex parts of the territory of NATO allies.

At the same time, Professor Riddervold emphasized that Europe and North America remain more closely interconnected than any other regions of the world, with over eight decades of dense cooperation behind them. The transatlantic relationship, she reminded the audience, has weathered major crises in the past and has at times emerged stronger as a result. Against this backdrop, the report set out to address a series of fundamental questions: how to make sense of current developments; how right-wing populism under Trump is affecting transatlantic relations; whether the present moment represents a qualitatively different rupture; and whether Europe is facing a more serious and long-term breakdown of a relationship long taken for granted.

To answer these questions, the report deliberately steps back from the volatility of the daily news cycle in order to provide a more systematic analysis. Professor Riddervold highlighted that the volume brings together leading experts on transatlantic relations, each drawing on extensive scholarly research to offer concise, focused analyses of how the relationship is changing and what these changes imply for Europe. She then outlined the structure of the report, explaining that it is organized around four foundational pillars that have historically underpinned the post-war transatlantic order: security, trade, international institutions, and liberal democratic values.

This framework draws on the work of G. John Ikenberry, who conceptualized the “Atlantic order” as resting on these four interlinked pillars, established under US leadership after the Second World War. The first pillar is the security alliance system; the second concerns trade and finance; the third encompasses multilateral institutions and rules; and the fourth consists of shared liberal democratic norms. Professor Riddervold further explained that Ikenberry identified two mutually reinforcing bargains underpinning the relationship. The “realist bargain” involved European acceptance of US leadership in exchange for security guarantees and access to US markets, technology, and resources within an open global economy. The “liberal bargain” linked security and economic openness to shared commitments to multilateralism and democratic governance, institutionalized through NATO, the World Trade Organization, and other international bodies. Together, these arrangements placed transatlantic relations at the core of the broader liberal international order.

Professor Riddervold stressed that the transatlantic relationship has never been based solely on strategic or economic interests. It has also functioned as a security community rooted in shared values, often described as part of the Pax Americana. Although US foreign policy has long been criticized for inconsistencies and double standards, she observed that successive administrations and Congresses prior to Trump broadly shared the conviction that democracies possess a unique capacity for cooperation and that European integration served US as well as European interests.

To capture possible trajectories of change, each chapter in the report distinguishes between three future scenarios. The first is outright disintegration or breakdown of transatlantic relations, potentially affecting one or multiple policy areas, driven by domestic political pressures and structural geopolitical shifts. However, Professor Riddervold emphasized that the relationship is also sustained by deep economic, institutional, and cultural bonds that may help stabilize it even under strain. This recognition led the authors to explore two additional scenarios: a second scenario in which the relationship weakens but “muddles through” via functional adaptation in areas of mutual interest, and a third scenario in which the relationship is redefined and potentially revitalized, for example through external shocks such as war or crisis, or through the emergence of a more united and capable Europe seen as a valuable partner by Washington. She also noted the possibility, explored later in the report, of a redefined transatlantic relationship shaped by right-wing populist convergence.

A Deep and Potentially Durable Rift in Transatlantic Relations

Across all four pillars, the report’s overarching conclusion is stark: transatlantic relations are experiencing what it terms a deep and potentially durable rift. Professor Riddervold identified two main reasons for this assessment. First, weakening is occurring simultaneously across security, trade, institutions, and values—a pattern unprecedented in earlier crises. Second, Trump does not perceive a strong transatlantic relationship as valuable, marking a sharp departure from post-war US policy traditions. Even beyond Trump, she argued, US domestic polarization and shifting strategic priorities mean that a return to previous patterns of relations is unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Despite this sobering diagnosis, Professor Riddervold emphasized that the report also identifies sources of cautious optimism. Several authors highlight functional adjustments that may allow cooperation to persist in specific areas, such as trade frameworks or defense-industrial cooperation linked to increased European defense spending. While the relationship may be weaker, such adaptations could gradually lead to a redefined partnership. Crucially, the report stresses that Europe has agency. When united, Europe possesses the capacity of a global power and can decide which values, institutions, and partnerships it seeks to uphold.

Concluding her presentation, Professor Riddervold summarized the report’s findings in the security and defense domain. Across multiple chapters, the authors argue that transatlantic security relations are entering a “post-American” phase, in which Europe can no longer rely on stable US leadership and must assume greater responsibility for its own defense. Whether the relationship muddles through or weakens further, the implication for Europe is the same: it must strengthen its security, defense, and strategic autonomy, reduce dependence on US military enablers, prepare for potential weakening of NATO commitments, and fully exploit its institutional, budgetary, and legal capacities. She concluded by stressing the need for a more unified and firmer European stance toward Washington before passing the floor to her co-editor for the subsequent sections of the report.

Assoc. Prof. Guri Rosén: Trade, Multilateralism, and the Erosion of the Rules-Based Order

In her presentation as one of the three editors of the ECPS report, Guri Rosén, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Oslo and Senior Researcher at ARENA – the Centre for European Studies – focused on the sections of the report addressing trade and international institutions. Building on the analytical framework outlined by her co-editor, she emphasized that transatlantic relations have historically rested on shared commitments to liberal trade principles and to rules-based institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO). A central conclusion emerging from the report’s trade section, she noted, is that the rise of populism has significantly weakened domestic support for trade liberalization, thereby accelerating a shift—particularly under the Trump administration—toward protectionism, unilateral tariff policies, and a transactional approach that challenges the foundations of the global trading system.

Dr. Rosén explained that the trade section of the report examines several interrelated dynamics: the growing tension between globalization and domestic autonomy, the dual shocks posed by China and the United States to the international trading system, the new disruptions following the second Trump administration, and the broader collapse of the WTO’s authority. She then provided a structured overview of the individual chapters.

The first chapter, authored by Eric Jones of the European University Institute, traces the evolution of the international trade system after the Second World War. Jones highlights the enduring tension between the international division of labor and the need for domestic policy autonomy. He revisits the post-war “embedded liberalism” compromise, which enabled global trade while allowing governments to protect welfare states and manage social dislocation. As globalization deepened, however, capital mobility increasingly overshadowed trade, constraining governments’ policy autonomy and generating domestic discontent—conditions that, Jones argues, have fueled contemporary populist movements. Two key insights emerge from this analysis: first, the existence of a “control dilemma,” reflecting the structural conflict between a globally integrated economy and national social protection; and second, the growing contestation of institutions designed to coordinate economic interdependence. While intended to prevent governments from exporting domestic political problems to one another, such institutions increasingly address politically sensitive issues, reinforcing perceptions that critical decisions are being removed from democratic control.

Against this backdrop, Alasdair Young of the Georgia Institute of Technology examines the drastic shift in US trade policy during Trump’s second term. Young argues that the Trump administration views trade as a zero-sum game in which the European Union is portrayed as benefiting unfairly at America’s expense. From this perspective, the existing EU–US trade framework appears highly fragile, a vulnerability underscored by recent disputes such as those surrounding Greenland. Young emphasizes that the Trump administration has repeatedly returned with new demands even after agreements have been reached, undermining trust and predictability. He raises the question of how the EU should respond, concluding that retaliation would likely inflict comparable economic costs on Europe and the United States. This assessment helps explain why the EU has largely pursued a strategy of waiting out the Trump period while focusing on internal reforms.

The third chapter in the trade section, written by Kent Jones of Babson College, analyzes the breakdown of the multilateral trading system. Dr. Rosén noted that Jones characterizes recent developments as a systemic rupture. The Trump administration, he argues, has abandoned core WTO principles, including the most-favored-nation clause, and has invoked national security exceptions to justify measures aimed primarily at reducing trade deficits. By bypassing WTO dispute settlement mechanisms and imposing discriminatory tariffs, the United States has violated the multilateral norms it once championed. This shift from rule-based governance to transactional bargaining forces the EU to negotiate on a sector-by-sector basis rather than relying on treaty-based frameworks.

The final chapter in the trade section, authored by Arlo Poletti of the University of Trieste, examines the political consequences of the “China shock”—the surge of Chinese imports since the early 2000s—on European labor markets and party systems. Poletti argues that this shock has contributed to the rise of far-right populist parties across Europe. As a result, the EU now finds itself constrained between a protectionist United States and an increasingly assertive China, a position made more difficult by Europe’s continued reliance on US security guarantees. Poletti contends that the EU should be prepared to credibly commit to retaliation in response to further US protectionist escalation, while also strengthening relations with other trade partners and fully deploying its expanded economic policy toolkit.

Dr. Rosén acknowledged that there are some differences of emphasis among the authors, but she stressed that their analyses converge on a shared strategic orientation. Taken together, the trade section recommends that the EU build economic strength and resilience while remaining anchored in a rules-based system. This entails prioritizing domestic objectives—growth, employment, and security—through the use of market power and regulatory tools, thereby forming the basis of a more competitive strategic autonomy. At the same time, member states must coordinate more effectively to avoid shifting the costs of globalization onto one another and to prevent a fragmented patchwork of national measures. Diversifying trade and investment ties across regions is also essential to reduce vulnerability to pressure from either the United States or China. Strengthening supply chains, technological capacity, and defense-related industrial bases is presented as integral to this effort, alongside continued engagement to keep the WTO functioning and to update its rules wherever possible.

Managing Multilateral Crisis without Escalation

Turning to the section on international institutions, Dr. Rosén explained that the report analyzes how right-wing populism and the “America First” agenda have disrupted the rules-based international order. While the EU regards multilateralism as central to its identity, the current US administration portrays international institutions as inefficient, elitist, and restrictive of national sovereignty. Mike Smith of the University of Warwick provides a conceptual framework for understanding what he terms a revolutionary assault on established international norms. Smith argues that while the first Trump administration was constrained by limited preparation, Trump’s second term operates with a far more radical and unconstrained agenda. He identifies three strategic options facing the EU: accommodating US demands, standing up to them, or working to build a more resilient form of multilateralism, potentially without US participation.

A further chapter by Edith Drieskens of KU Leuven examines the turbulence confronting the United Nations system. Dr. Rosén noted that a series of US executive orders mandating reviews of international organizations and foreign aid have resulted in severe budget cuts, pushing many UN agencies into survival mode. Organizations such as UNESCO have been singled out for defunding or potential withdrawal, while US support for the Sustainable Development Goals and for diversity and inclusion norms has been curtailed. Drieskens argues that the EU has adopted a cautious posture, refraining from overt criticism of the United States to avoid retaliation in areas such as trade or NATO cooperation.

Climate governance is addressed in a chapter by Daniel Fiorino of American University, who analyzes the consequences of the United States’ second withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement. Fiorino argues that the administration has shifted from mitigation toward an “energy emergency” posture, dismantling regulatory constraints on fossil fuel development. While the most immediate effects are domestic, he suggests that US disengagement risks ceding technological and economic leadership in the green transition to Europe and China. From his perspective, the EU’s most pragmatic strategy is to maintain its Green Deal policies while waiting for potential change in the US political cycle.

The final chapter, by Frode Veggeland, examines the US withdrawal from the World Health Organization in 2025. Veggeland argues that global health governance is experiencing turbulence as funding becomes increasingly fragmented and earmarked. In this context, the EU must deepen cooperation with like-minded partners and assume a more prominent role in global health security, potentially filling the vacuum left by US disengagement through coalition-building as a form of soft power.

Dr. Rosén concluded by emphasizing that, across both trade and international institutions, the report’s authors view multilateral frameworks as core instruments of European power and legitimacy. Rather than waiting passively for renewed US engagement, the EU should combine short-term adaptation with selective pushback and long-term institutional strengthening. This approach, she argued, would allow Europe to protect its agency, defend core norms and interests, and contribute to more resilient international institutions capable of withstanding funding shocks, obstruction, and shifting power balances.

Professor Jessica Greenberg: Moving from Muddling Through to EU Leadership

In her presentation as one of the three editors of the ECPS report, Jessica Greenberg—Professor of Anthropology at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and a political and legal anthropologist specializing in Europe, human rights, social movements, democracy, and law—introduced and synthesized the report’s final section on democratic values. She described the report as both rewarding and collaborative to produce alongside her co-editors and contributing authors. She framed her remarks under the title “Moving from Muddling Through to EU Leadership,” signaling an intention to offer a more forward-looking assessment, even while acknowledging the gravity of the present transatlantic moment.

Professor Greenberg first underscored the methodological distinctiveness of the democratic values section. Unlike the report’s other sections, which are anchored primarily in international relations, political economy, or institutional analysis, this section is heavily shaped by sociological and anthropological approaches to institutions. She observed that democracy and populism are notoriously difficult to define and practice, often triggering a familiar “we know them when we see them” reaction. The aim of the section, she argued, is to move beyond such first-blush recognitions by probing how democracy, liberalism, and rule of law are lived, practiced, and reproduced inside institutions. Populism, in turn, is examined not merely as rhetoric or political style but as a “lifeworld”—an everyday, granular set of perceptions, dispositions, and practices. This emphasis, she explained, is critical for understanding democratic resilience, since democracy and rule of law operate through daily, practice-based dimensions that can be eroded gradually and normalized in subtle ways.

To illustrate the section’s conceptual framing, Professor Greenberg referenced a striking passage by Douglas Holmes, one of the contributors, which characterizes populism as a creative force capable of shaping not only politics but also feelings, thoughts, moods, intimacies, actions, and even perceptions of justice and reality. For Professor Greenberg, this formulation captured the section’s analytical ambition: to understand how populism works from the inside out, at the level where institutions and everyday life intersect.

She then turned to the first two chapters of the section—by Douglas Holmes and Saul Newman—which she described as mapping “populism’s paradoxes.” These chapters, she argued, establish the institutional and cultural terrain on which any effective response to populist capture must be built. Among the key paradoxes is that populist politics often presents itself as anti-elitist, anti-establishment, and anti-institutional, yet simultaneously relies on institutional frameworks at the international and European Union levels and pursues institutional capture domestically. The chapters emphasize that populist actors do not simply confront institutions from the outside; they rework them from within, altering their internal logics and operational “genetic code.” Understanding this reconfiguration, Dr. Greenberg suggested, is indispensable to designing meaningful responses.

A second paradox concerns populism’s relationship to nation and network. Populist politics tends to focus on national frameworks and racialized, homogeneous notions of “the people,” yet it is also increasingly transnational in practice. Populist movements share strategies, repertoires, discourses, and social media memes across borders, producing an internationalized—and in a counterintuitive sense, “cosmopolitan”—populist landscape. A third paradox, as Professor Greenberg presented it, is that populism functions as a critique of liberalism: it directly challenges liberal claims to provide representation, solidarity, care, justice, and inclusive political membership. Recognizing how populism positions itself against liberal institutions is, she argued, central to understanding its appeal and operational power.

Professor Greenberg proceeded to summarize the subsequent chapters, each offering a different window onto the erosion and contestation of democratic values. Reuben Anderson’s chapter, “The Liberal Bargain on Migration: Convergence in Securitizing Borders,” examines how framing migration as a security problem undermines meaningful integration and constrains democratic commitments to pluralism, rule of law, and inclusive governance. Professor Greenberg highlighted Anderson’s analysis of a “two-faced” migration regime on both sides of the Atlantic: migrants are funneled into labor-hungry economies, including through illegalized and exploitable work, while governments simultaneously stage “tough” crackdowns at physical borders and in third countries. The result, Anderson argues, is the expansion of an enforcement industry and a self-reinforcing spiral of securitization, displacing opportunities to address migration rights and labor-market needs in a more transparent and democratic manner.

The following chapter, Robert Benson’s “Illiberal International: The Transatlantic Rights Challenge to Democracy,” develops the theme of transnational far-right mobilization. Professor Greenberg emphasized Benson’s argument that such movements cannot be understood in isolation because they are deeply networked across borders. Think tanks, party foundations, legal advocates, and online platforms form alliances that circulate strategies, legal models, ideological frames, and digital tactics aimed at weakening democratic norms. Professor Greenberg drew attention to Benson’s description of a “transnational ecosystem of distrust” that corrodes confidence in electoral integrity, journalism, and scientific expertise. In her account, the chapter portrays this as intentional, organized, sophisticated, and strategically coordinated—requiring both place-based countermeasures and broader transnational coordination.

The final chapter in the section, by Albena Azmanova, centers on precarity and democratic resilience. Professor Greenberg presented this chapter as demonstrating how inequality, social vulnerability, and the affordability crisis fuel distrust in government and create fertile ground for grievance politics. She suggested that Azmanova’s analysis reinforces a core implication running through the section: robust social welfare policies are not peripheral to democratic stability but central to it. In this view, social policy is a key component of democratic resilience and a substantive counter-politics to populist mobilization.

The Transatlantic Alliance “As We Know It” Is Effectively Over

Having summarized the chapters, Professor Greenberg widened the lens to offer concluding reflections that also drew together threads from the report’s other sections. She argued that the transatlantic alliance “as we know it” is effectively over, citing President Trump’s threats to invade Greenland and the possibility that NATO itself could be destabilized. In her formulation, Trump’s repudiation of multilateral cooperation in trade and security, rejection of rule of law domestically and international law abroad, and nativist political stance collectively undermine the foundational commitments of the post-war alliance. The United States, she argued, has replaced cooperation and liberal trade with zero-sum protectionism and tariffs, while Trump’s disdain for democracy and global legal order finds affinity with populist forces on both sides of the Atlantic.

Yet Professor Greenberg also insisted on a crucial counterpoint: the alliance was never merely a technocratic handshake among bureaucrats. It was a living set of commitments that provided institutional architecture for multilateral cooperation, created pathways to respect sovereignty while binding national interests through shared visions of peace and security, and linked prosperity to democratic participation, human rights, constitutional guarantees, and equality. She invoked the breadth of actors who helped realize these commitments—from local communities and policymakers to human rights advocates and entrepreneurs—turning abstract principles into lived realities.

From this diagnosis, Professor Greenberg drew a stark strategic imperative: as long as Donald Trump remains president, he will continue to destabilize whatever trust remains in the decades-long alliance, and Europe cannot afford to wait, minimize the danger, or adopt a posture of denial. Europe, she argued, must “go it alone,” and it must act immediately. While she acknowledged that calls for a more unified Europe are not new, she argued that far more specificity is needed, and that the report’s four-pillar framework remains a useful guide for action. The EU, she maintained, is well positioned to lead in international cooperation, trade, security, and democratic values—if it consolidates internal integration, strengthens economic and financial coordination, and takes a firmer, more coherent line toward Washington beyond appeasement and passive wait-and-see strategies.

Professor Greenberg emphasized that the EU possesses political and financial leverage and should be prepared to use it. The United States, she argued, needs a unified EU in responding to Russia and China, in both security and trade, which positions Europe to advance strategic autonomy while serving as the most credible partner for strengthened bilateral and plurilateral arrangements. She reiterated themes of the report’s security recommendations: a more coherent long-term European security strategy, a stronger European defense industrial base, and more predictable support and guarantees for Ukraine—combined with careful management of relations with China and other partners. Strength, flexibility, and conviction, she argued, must guide the EU’s posture, enabling it to seize opportunities for cooperation when aligned interests arise—even as the United States becomes less reliable.

At the domestic level, Professor Greenberg echoed the report’s emphasis on prioritizing internal policy goals and using the EU’s market power and regulatory tools to support growth, jobs, and security at home, while avoiding race-to-the-bottom dynamics that reward fragmentation. Such an approach, she argued, would foster unity and build collective solutions to shared challenges—from precarity and public health to climate crisis. She also underscored the importance of sustaining international institutions as central to European power, legitimacy, and interests, with multilateral networks promoting rule-setting, transparency, and democratic procedures.

Finally, Professor Greenberg returned to the normative core of her section: a unified Europe must be defined by reasoned action and a strong ethical foundation. Democracy, pluralism, and rule of law cannot function as afterthoughts or merely procedural commitments. In her assessment, EU approaches to precarity, migration, and climate have at times reflected backsliding or even capitulation to populist pressures. Across the report, she noted, experts emphasize the necessity of confronting inequality, affordability crises, and institutional distrust if Europe is to lead democratically. Values, she concluded, must be made credible through concrete action: rule-of-law commitments, inclusion, human-rights-compliant migration, and renewed commitments to sustainability, health, and well-being across both urban and rural spaces.

In Professor Greenberg’s closing argument, Europe cannot outpace populist “shock and awe” tactics—rapid policy shifts, disregard for legal norms, and conspiratorial narratives designed to overwhelm and demobilize. Instead, Europe must counter destabilization with substance, endurance, clear communication, pragmatic hope, and institutional leadership. She ended on a horizon of conditional optimism: if Europe acts now to uphold the promise of the broken alliance, it can preserve a democratic home to which a future United States might one day return.

Q&A Session

The Q&A session opened with an intervention by Robert Benson, affiliated with the Center for American Progress (CAP), who posed two interrelated questions to the editors and panelists. First, he observed that the discussion had not drawn a clear analytical distinction between left-wing and right-wing populism and asked whether populism could function as an emancipatory political force—or even as a potential antidote to the form of populism associated with the Trump White House. Referencing ongoing debates within the US Democratic Party, Benson framed the issue as a strategic dilemma between more radical or more centrist political pathways.

His second question addressed the apparent contradiction inherent in transnational nationalism. Benson queried how nationalist parties such as Germany’s AfD could simultaneously align with the Trump administration and with counterparts like France’s National Rally, given nationalism’s ostensibly inward-looking logic. He suggested that such alliances might be better understood as instrumental rather than ideological, serving common ends such as profiteering, corruption, and the extraction of political or economic concessions from a fragmented Europe—an interpretation he linked to recent US national security thinking.

Responding first, Jessica Greenberg emphasized that, for the purposes of the report, the key analytical takeaway was not the normative distinction between left- and right-wing populism, but the observable political energy generated by both. She noted that populist movements across the ideological spectrum have mobilized significant loyalty, grassroots participation, and youth engagement, effectively capturing a sense of renewed citizenship and political agency. Greenberg argued that liberal democratic institutions cannot afford to relinquish this mobilizing capacity, stressing that liberalism must inspire hope and engagement rather than operate solely as a reactive force.

The second response came from Riccardo Alcaro, who addressed the question of transnational nationalist convergence. He argued that while alliances between nationalist parties and the Trump administration are inherently unstable, they persist because of a shared understanding of political enemies—primarily internal rather than external. This convergence, he suggested, transforms transatlantic relations from a strategic partnership into a politicized and ideologized framework. In such a configuration, transatlantic ties serve less to advance shared interests than to legitimize domestic political struggles against migrants, liberal institutions, and perceived “globalist” elites, a dynamic with particularly far-reaching implications for Europe.

The second round of the Q&A session was initiated by Kristo Anastasov, who framed his intervention from a geopolitical and historical perspective. Commending the panel for avoiding an exclusively ideological reading of contemporary transatlantic tensions, he argued that the report compellingly invited deeper engagement. Anastasov contrasted the current political landscape in the United States—characterized, in his view, by the existence of “two American nations” and a level of polarization historically associated with civil conflict—with the European situation. Despite the rise of populism and persistent divisions, he maintained that Europe continues to rest on a cross-ideological basis of consensus that prevents systemic rupture, with Hungary standing as a partial exception rather than the rule.

From this perspective, Anastasov suggested that Europe’s strategic task is not to replicate the American experience but to position itself as a stabilizing counterpoint—restoring damaged transatlantic links where possible while simultaneously forging new ones. He cited the European response to the Greenland crisis as illustrative of both strengths and weaknesses in Europe’s approach. On the one hand, Europe demonstrated unity and institutional capacity; on the other, he argued that hesitation—such as the decision not to seize frozen Russian assets held in Belgium—was interpreted by the Trump administration as weakness, prompting renewed rhetorical escalation. By contrast, Anastasov pointed to initiatives such as the Mercosur agreement and negotiations with India as examples of effective demonstrations of European strength, though he lamented that these efforts had been partially undermined by internal institutional delays. He concluded by asserting that appeasement and coexistence are ineffective in dealing with a deal-breaking counterpart, insisting that consistency and credible displays of strength are essential.

Responding, Marianne Riddervold thanked Anastasov for his remarks and for encouraging engagement with the report. She reiterated that the report’s objective was precisely to provide a systematic, conceptually grounded analysis rather than reactive commentary. Riddervold emphasized that all contributing authors converge on the recommendation that Europe must act firmly and collectively. At the same time, she acknowledged the structural dilemma facing Europe: persistent dependencies on the United States, particularly in security and defense, necessitate continued cooperation even as Europe works to reduce those dependencies. She noted that the Trump administration’s tendency to conflate trade and security—such as linking trade negotiations to Ukraine—poses an unprecedented challenge. Nevertheless, she observed that the European Union has demonstrated increasing speed and cohesion in responding to successive crises. While acknowledging delays and internal disagreements, she characterized the EU as an exceptionally flexible system capable of adapting creatively within its legal framework, including through partial or staged implementation of contested agreements.

Guri Rosén added that divergences among the report’s authors reflect real strategic tensions rather than analytical weakness. Some contributors stress the importance of demonstrating strength and leadership, while others argue that a “wait-it-out” strategy minimizes economic and political costs. Rosén argued that the report’s four-pillar framework—security, trade, institutions, and values—reveals the necessity of integrated thinking across policy domains. The central challenge for Europe, she concluded, lies not only in responding to external pressures but also in overcoming internal coordination difficulties. Determining whether to assert strength or exercise restraint ultimately depends on evaluating Europe’s collective interests across all sectors simultaneously, rather than in isolation.

The third round of the Q&A broadened the discussion to questions of strategy, narrative, internal European divisions, and the structural meaning of contemporary populism. Sandra Kaduri opened by asking whether a political tipping point might be emerging in the United States and whether European actors were fully exploiting this moment. Referring to subnational engagement at the most recent COP in Brazil—where over one hundred US governors and officials participated—she suggested that Europe might bypass the Trump administration by engaging more systematically with American actors beyond the federal executive. Kaduri also emphasized the potential of public opinion, polling, and values-based communication, arguing that majorities remain concerned about polarization and receptive to democratic norms, and questioning whether existing opportunities for narrative leadership were being missed.

A related intervention came from Becky Slack, who welcomed the report’s attention to framing and narrative. She posed a practical question regarding implementation: how the report’s recommendations on narrative could be operationalized, and which actors—political, institutional, or societal—would need to serve as partners in translating analytical insights into concrete communicative strategies capable of reducing polarization and strengthening democracy.

Reinhard Heinisch shifted the focus inward, challenging what he perceived as an overly homogeneous portrayal of Europe. He asked the panel to address persistent divisions between Eastern and Western Europe, their interaction with transatlantic relations, and the extent to which the United States might exploit these internal fractures—alongside what Europe could do to mitigate such vulnerabilities.

Offering a reflective comment rather than a direct question, Douglas Holmes introduced a historical and anthropological perspective. Drawing on his long experience interviewing Members of the European Parliament, he cautioned against linear or moralized readings of history. Holmes noted the paradox that the framers of the US Constitution—figures he described provocatively as religious fanatics and populists—produced one of the world’s most liberal political documents. From this, he suggested that the current moment may also contain unexpected possibilities, and he concluded by characterizing Trumpism less as an expression of American strength than of systemic weakness—an interpretation he offered as a potential source of strategic confidence.

Responding on behalf of the panel, MEP Radan Kanev addressed several of the themes raised. He argued that cooperation among European nationalist forces presents a greater challenge for those actors themselves than alignment with American dominance. Illustrating this point, he recounted the Romanian elections, where Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s support for a Romanian far-right candidate backfired, alienating ethnic Hungarian voters and inadvertently strengthening a liberal candidate. Such missteps, Kanev suggested, are likely to recur in attempts to build a coherent “nationalist international.”

At the same time, Kanev warned that history offers many examples of nationalist leaders willingly subordinating themselves to stronger external powers, citing Vichy France as a paradigmatic case. He expressed particular concern about Eastern Europe, where post-communist power structures have normalized dependency, making alignment with distant American power appear safer than genuine sovereignty.

Kanev concluded with a controversial but central argument: building a strong Europe requires distinguishing between nationalist and populist actors based not on ideological sympathy, but on their commitment to an independent Europe. Given the fragmentation of today’s political landscape and the erosion of traditional grand coalitions, he argued that European consensus-building must expand beyond familiar alliances to include Greens and selected conservative forces unwilling to act as external proxies—an inherently difficult but unavoidable task for Europe’s political future

Conclusion

The ECPS panel at the European Parliament underscored a central and sobering conclusion: transatlantic relations are no longer governed by inherited assumptions of stability, convergence, or automatic solidarity. The re-election of Donald Trump has not merely revived earlier tensions but has accelerated a deeper structural shift in which populism, domestic polarization, and transactional power politics increasingly define the terms of engagement. As the discussions repeatedly emphasized, this transformation affects not only external relations between Europe and the United States, but also the internal cohesion, democratic resilience, and strategic self-understanding of the European Union itself.

Across the panel, a clear analytical consensus emerged around three interlinked insights. First, the weakening of transatlantic relations is occurring simultaneously across security, trade, international institutions, and democratic values—an unprecedented convergence of pressures that cannot be addressed through isolated or short-term fixes. Second, Europe retains agency. While it cannot shape US domestic politics, it can determine whether fragmentation, dependency, and narrative passivity define its response, or whether unity, strategic autonomy, and institutional leadership prevail. Third, populism must be understood not only as a political style or ideology, but as a governing logic capable of reshaping institutions from within, eroding norms gradually, and normalizing democratic backsliding unless actively countered.

The report and the panel discussions converge on the necessity of moving beyond reactive “muddling through.” Strengthening European defense capacity, asserting regulatory sovereignty, reinforcing multilateral institutions, and addressing socioeconomic precarity are not parallel agendas but mutually reinforcing dimensions of democratic resilience. Equally, narrative and coalition-building emerged as indispensable tools: Europe’s response must speak not only to elites and institutions, but to publics increasingly vulnerable to polarization, distrust, and grievance politics.

Ultimately, the panel framed the current moment not as the end of transatlantic cooperation, but as the end of its taken-for-granted form. The future relationship—if it is to endure—will depend on a more autonomous, coherent, and values-grounded Europe capable of engaging the United States as a partner when possible, resisting it when necessary, and leading where leadership is absent. The challenge, as the report makes clear, is no longer whether Europe should act, but whether it can act decisively enough, and soon enough, to shape the order emerging around it.