Despite the AfD’s strong performance in Germany’s Sunday elections, securing nearly 21% of the vote and dominating in the East, Professor Jonathan Olsen argues that the party faces a ceiling in its growth. “Opinion polls consistently show that around 80% of Germans do not support the AfD,” he notes, emphasizing its high negative ratings. While the AfD has solidified its base in the East, its influence in the West remains limited, requiring a broader appeal to expand further. Professor Olsen highlights that migration and security remain the party’s key mobilization issues, while economic concerns, though present, rank lower in importance for its voters.

Interview by Selcuk Gultasli

In a comprehensive interview with the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), Professor Jonathan Olsen, Chair of the Department of Social Sciences and Historical Studies at Texas Woman’s University, offered his insights into the Alternative for Germany (AfD)’s recent electoral performance. While the party’s near 21% result in the 2025 German elections signals strong support—particularly in eastern Germany—Professor Olsen argues that its growth potential may be reaching a ceiling. “Opinion polls have consistently shown that around 80% of Germans do not support the party,” he noted. “The AfD has the highest negative ratings of any political party in Germany.”

Despite its success, Professor Olsen highlights that the AfD’s ability to broaden its voter base remains uncertain. “They remain the largest opposition party, securing nearly 21% of the vote and mid-30% in Eastern Germany. But moving forward, the key question will be: How do they expand beyond their current level of support?” He suggests that, while the AfD has solidified its position in the East, its influence in the West remains limited. “They receive about twice as much support in the East as in the West. If I were advising the AfD, I would recommend they focus on broadening their appeal in the West and refining their messaging to attract a wider voter base.”

One of the more striking aspects of the AfD’s campaign was its issue selection. Professor Olsen describes the party as a “populist issue entrepreneur,” effectively capitalizing on migration and domestic security as central themes. “I don’t see that the AfD mobilized any new issues except for the economy and the performance of the Ampel coalition (Ampelkoalition). Migration was by far the most important issue driving their vote, followed closely by domestic security,” he explained. Economic concerns ranked much lower in priority, though Professor Olsen points out that 75% of AfD voters expressed concerns about rising prices and future financial security.

Despite some international attention, Professor Olsen downplays the impact of endorsements from figures like Elon Musk and J.D. Vance on the AfD’s performance. “There was no discernible bump from Musk’s endorsement or from J.D. Vance’s and Trump’s implicit support. So, I think it had zero effect,” he stated.

Looking ahead, the AfD’s position within both Germany and the broader European far right remains complicated. While it seeks alliances with transnational populist movements, many European far-right parties still consider it too extreme. “Even Marine Le Pen’s National Rally and Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy have distanced themselves from the AfD,”Professor Olsen noted. As the party continues to grow in the East while struggling to expand in the West, its long-term trajectory remains a crucial question for German and European politics.

Here is the transcription of the interview with Professor Jonathan Olsen with some edits.

The AfD’s Growth Is Strong, but Its Ceiling May Be in Sight

Professor Olsen, thank you very much for joining our interview series. Let me start right away with the first question: You observed the German elections in Germany. How do you interpret the performance of the AfD in the German elections, in which it almost doubled its vote since the last election in 2021? Did its electoral strategy evolve compared to previous elections?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: I think the AfD’s performance can be considered a strong one. The party is certainly pleased with the outcome. They didn’t exceed some expectations—some thought they might reach 21 or 22%—but they ended up just under 21%, so it can’t be characterized as disappointing. This result may suggest that there is a ceiling for AfD support. They remain the largest opposition party, securing nearly 21% of the vote and reaching the mid-30% range in Eastern Germany. It was a very successful election for them, but moving forward, the key question will be: How do they broaden their voter base? How do they expand beyond their current level of support? Because, in my view, there seems to be a limit to their electoral growth.

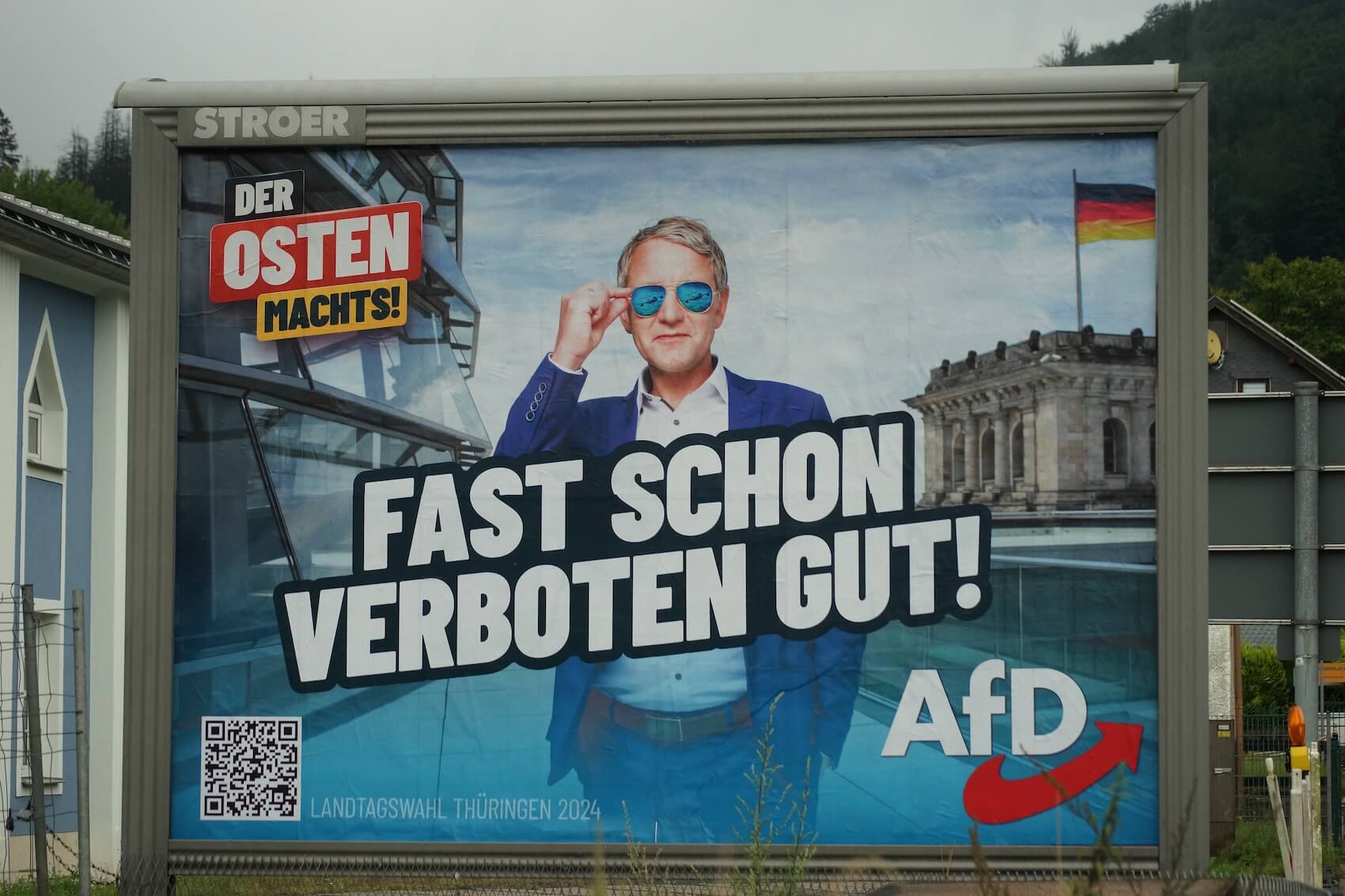

As for your second question—did their electoral strategy evolve compared to previous elections? I wouldn’t say it changed significantly. However, if you examine their campaign posters—I spent a lot of time walking around the city analyzing different posters, and I previously conducted research with my co-author on AfD election posters in 2017 and 2021—there is a noticeable shift. While I haven’t done a systematic study of the 2025 election, a first glance at their campaign materials suggests a much more mainstream presentation. Their advertising appears more conventional, more in line with other parties, and lacks the provocative posters seen in 2017.

The 2025 campaign placed significant emphasis on Alice Weidel as their lead candidate. When I examined their posters, nothing stood out as particularly different from other parties. Their strategy largely capitalized on the issues that were already prominent in public discourse—migration and domestic security—particularly following high-profile attacks involving asylum seekers in various parts of Germany. These events effectively handed the AfD its key campaign themes. Additionally, the CDU’s response to these issues, which in some ways reinforced the AfD’s position, made it even easier for the party to highlight its main message.

Do you think Elon Musk and J.D. Vance’s endorsement of the AfD had any effect on the party’s performance?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: No, I don’t think it had any effect. If you look at the AfD’s polling over the last year or so, it has stayed pretty steady, right around 20%. There was no discernible bump from Musk’s endorsement or from J.D. Vance’s and Trump’s implicit endorsement of the party. So, I think it had zero effect. It did not have any negative effect that I could tell—that is, I don’t think it drove people away from the AfD, but it certainly didn’t drive people to vote for the AfD either.

AfD’s National Expansion Remains Uncertain

The AfD has seen significant support in the elections, particularly in eastern Germany. How do you interpret their latest electoral performance? Does it signal a deepening of their influence or a potential ceiling to their growth?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: Well, to address your last question first, which I partially answered earlier, I see a potential ceiling to the AfD’s growth. Opinion polls have consistently shown that around 80% of Germans do not support the party. The AfD has the highest negative ratings of any political party in Germany.

If you’re looking at people who didn’t vote for the AfD—not always the best way to gauge their future potential—you still have to consider that 80% of Germans did not vote for the AfD in 2025. As part of this election trip, we had a representative from the AfD speak to us, and I asked him what the party could do to broaden its support. He didn’t have much of an answer. It seems the AfD expects political issues to fall into their lap and assumes that the failure of mainstream parties to address key problems will automatically boost their support. But I’m not convinced that’s the case. I don’t see their support growing dramatically unless they take proactive steps to make themselves more appealing to a broader segment of German voters.

Now, in eastern Germany, the situation is different. This is more of a West German problem than an Eastern German one. In Eastern Germany, the AfD is the largest party. If you look at the first vote election results in East and West, it’s predominantly the CDU and CSU in the West, while in the East, it’s primarily the AfD. They secured 35–36% of the vote in Eastern Germany, making them the dominant party there. It reminds me of the vote totals Die Linke was getting 10–15 years ago, but which they no longer achieve.

The AfD has clearly solidified its base in Eastern Germany. Although they perform relatively well in the West, they still lag significantly behind other parties there. They receive about twice as much support in the East as in the West. I believe the average was 34% in the East compared to around 18% in the West. If I were advising the AfD, I would recommend they focus on broadening their appeal in the West and refining their messaging to attract a wider voter base. That’s how I would approach it.

AfD’s Success Driven by Migration and Security, Not New Issues

Your research highlights the AfD as a “populist issue entrepreneur.” What new issues has the party successfully mobilized in this election?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: This was interesting because I don’t see that the AfD mobilized any new issues except for the economy and the performance of the Ampel coalition (Ampelkoalition). If you look at the issues the AfD was running on and that were important to their voters, it was migration and domestic security. After that, it was the performance of the Ampel coalition, specifically regarding the economy and energy.

Whether they have a coherent answer is another question. I don’t think so, and I know that most German voters didn’t find their answers to economic issues particularly convincing. However, that may not matter much to their core voters. For them, the most important thing is that the AfD continues to stress migration and domestic security issues. Whether they can develop their economic message in the future is an important question for broadening their voter base. Finding a coherent and convincing economic platform will be crucial for the AfD if they want to expand their appeal.

I wanted to look at this because there were some interesting exit polls available on Tagesschau. Looking at the issues that were important to voters overall, domestic security was the top issue, tied with economic and social security. After that came migration, followed by economic growth.

For AfD voters specifically, migration was by far the most important issue driving their vote, followed closely by domestic security. Far behind those were concerns about economic growth, rising prices, and other issues. So, it’s clear that for AfD voters, the party’s primary appeal comes from its stance on migration and domestic security, with much of the security debate tied to migration—curbing violence by asylum seekers, for example. Economic issues rank far lower in importance. Right now, this prioritization works for them, but if the AfD wants to broaden its voter base in the future, they will have to develop more convincing economic solutions.

Far-Right Degrowth: A Mix of Nationalism, Eco-Asceticism, and Climate Skepticism

How does the far right’s concept of “degrowth” differ from the left’s vision, and what role does this play in its political messaging?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: So that’s a real shift in gears, moving from the AfD to the broader far right. The AfD, like most populist far-right parties, is more of an anti-environmental party than an environmental one. While they talk about alternative environmental solutions, their primary concern is denying climate change or denying that it is man-made. They advocate for a return to traditional fossil fuels and are strongly opposed to alternative energy sources. There is nothing in the AfD’s program that suggests any real concern for environmental issues.

However, the broader far-right milieu in Germany and elsewhere takes some of these issues more seriously. Unlike the AfD, some far-right groups do not deny climate change or its human causes. They support some use of alternative energies and acknowledge major environmental challenges. The most the AfD does in this regard is to conceptualize a nationalist environmental policy. They frame themselves as the true environmentalists, arguing that only patriots—those who love their homeland—can truly protect the environment. They mention environmental initiatives, but their proposals are quite limited.

This is where degrowth comes in. Unlike the broader far right, the AfD—like almost all other populist far-right parties—does not question economic growth. Degrowth is a concern primarily for other far-right groups and circles that take environmental issues more seriously. That being said, this remains a relatively small segment of the far right.

Their conception of degrowth aligns with what Bernhard Forchtner and I called “eco-asceticism.” This vision promotes self-renunciation, self-control, and a reduction in consumption. In this regard, it is not entirely different from the left’s vision of degrowth. However, where they diverge is in their views on global capitalism. The left firmly identifies global capitalism as the main driver of environmentally destructive economic growth, whereas the far right is more ambiguous. They are certainly against globalism, but not necessarily against all forms of economic growth.

Another key difference is that some segments of the far right that discuss degrowth also tie it to an ethno-nationalist vision of the nation and a concept of ethnocultural purity. You don’t find this element in the left’s vision of degrowth.

AfD Remains an Outlier but Gains Leverage in German Politics

In your view, has the AfD managed to fully integrate into the German political system, or does it remain an outlier? How has the response of mainstream parties impacted its trajectory?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: Well, it still remains an outlier because no other party is willing to form a coalition with it. The AfD is trying to bide its time—returning to a point I made earlier, the AfD’s strategy at this stage seems to be to wait it out. That is, they are not going to do much differently from what they have done before. They are not actively trying to increase their vote share; instead, they are counting on the decline of mainstream party support, which would eventually leave conservatives with no other option than to form a coalition with the AfD. That appears to be their strategy. So, the AfD is definitely still an outlier in the political system. However, its growing vote totals are making it harder for other parties to form coalitions—both at the national and state levels—and to completely ignore the issues it is raising.

How has the response of mainstream parties impacted the AfD? Well, a couple of weeks before the election, Friedrich Merz tried to push through a non-binding resolution on limiting migration in a particular way, and he had to rely on AfD support to get it passed. He didn’t want to; he had expected other parties to support it, but it turned out to be a miscalculation on his part. Many observers saw that as providing a certain degree of legitimation to the AfD and the far right. People have been discussing the Brandmauer—the firewall against the AfD—as if it is not completely down, but at least damaged.

I think the response of mainstream parties is going to be really important for the AfD’s trajectory in the future. If they can continue to marginalize the AfD—treating it as a non-legitimate party—while at the same time addressing the concerns that matter to AfD voters and a broader segment of the German electorate, then they have a chance of decreasing the AfD’s vote share.

In other words, I believe the next four years will be crucial—assuming the coalition lasts its full term. Whatever government forms next, most likely a CDU/CSU and SPD coalition, it will be essential to address key issues in a way that satisfies German voters. If they succeed, I think we will see a decline in the AfD’s vote totals. If they fail—especially if the new coalition resembles the Ampelkoalition in its inability to resolve basic concerns—then the AfD will likely continue to receive 20% or more of the vote.

AfD Support Driven More by Perceived Decline Than Economic Hardship

Many analysts highlight economic anxieties and globalization backlash as drivers of AfD support. How much of their success do you attribute to economic factors versus cultural or identity-based appeals? To what extent did dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of recent crises, such as the economy or migration, contribute to AfD’s support in Sunday’s elections?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: I’ll answer that last question first, and it contributed a lot to the AfD’s support. Migration, as we’ve discussed, was by far the biggest issue. The economy also played a role, even though it ranked lower on AfD voters’ list of concerns. That doesn’t mean it was unimportant. Certainly, the Ampel coalition’s perceived incompetence and inability to get things done had a significant effect on the AfD’s vote.

Regarding economic factors versus cultural and identity-based issues, I don’t think you can completely separate the two. If you look at AfD voters objectively, the majority are not economic losers. In terms of income levels and other economic markers, they are not primarily drawn from the unemployed or lower-income groups. Instead, the AfD’s support comes from middle- and higher-income levels. So, it is not necessarily their objective economic situation that is driving AfD voters. However, there is a strong sense of anxiety among AfD voters that they are losing—that they are falling behind compared to other groups.

This reflects a distinction between subjective perceptions and objective markers of economic status. Looking at the available data, Tagesschau exit polling showed that domestic security played a far larger role among AfD voters than among any other party’s electorate, with 33% citing it as a top concern. Migration, as expected, was twice as significant for AfD voters compared to supporters of any other party. Conversely, economic growth was a much lower priority for AfD voters compared to other parties.

One particularly interesting finding is that 75% of AfD voters expressed strong concerns that rising prices would make it difficult for them to pay their bills. Similarly, 74% feared that their standard of living could not be maintained in the future, and 71% were deeply concerned about having enough money in old age. So, while AfD voters clearly have economic anxieties—especially regarding globalization—these concerns are not necessarily grounded in their objective circumstances but rather in their subjective perceptions and fears about economic decline.

AfD Seeks Alliances but Remains ‘Too Extreme’ for Europe’s Far Right

Given the rise of far-right parties across Europe, do you see the AfD aligning more with transnational populist movements, or is its strategy still largely domestically driven?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: I see the AfD trying to align itself more with transnational populist movements. It does seek out international partners, particularly in Europe. However, interestingly enough, the AfD is still viewed as too extreme by many far-right populist parties—certainly by the National Rally in France, which did not want the AfD as part of its group in the European Parliament. It is also seen that way by Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy, as the AfD is considered too far to the right. Some of the party’s controversial statements regarding the Nazis, the Holocaust, and the war have contributed to this perception.

As a result, the AfD currently stands somewhat apart from other far-right populist parties in Europe, even though they share many of the same issues. Migration is a central concern for all far-right populist parties, as is globalization. Anti-EU or at least highly EU-skeptical sentiments are common across these parties, as is the cultivation of nationalism and national identity. However, the AfD remains farther to the right than most.

Domestically, the AfD is primarily focused on appealing to East Germans, where some of its more controversial statements on National Socialism have not appeared to harm its electoral support. However, these same controversies have damaged its relationships with other far-right populist parties in Europe.

AfD’s Environmental Stance: Nationalist Framing or Anti-Green Identity?

Does the AfD’s environmental discourse resonate with voters, or is it more of a symbolic strategy aimed at rebranding the party’s ideological image?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: Whatever pro-environmental discourse the AfD has is not really something that resonates with voters. When you look at the AfD’s messaging, it is primarily focused on anti-environmental positions. It advocates for a return to fossil fuels, opposes alternative energy sources like wind power, rejects subsidies for electric vehicles, and promotes climate change denial or skepticism.

The environmental aspects of the AfD’s messaging are mostly framed within a nationalist perspective. This includes rhetoric about protecting the German environment, preserving the homeland, and safeguarding natural spaces. However, this nationalist environmentalism is minimal and does not seem to attract many voters.

The interesting question moving forward is whether the AfD—or other populist far-right parties—will attempt to moderate their stance on environmental issues, climate change, and related policies. It remains to be seen whether they will consider such a shift too risky, as their anti-environmental message is distinct from that of any other party. If they were to embrace more pro-environmental policies, they might lose their unique positioning in the electoral marketplace.

And lastly, Professor Olsen, how has the AfD framed issues like sustainability and environmental protection? Does their rhetoric on ecology differ from traditional far-right parties, and how do they position themselves against the German Greens?

Professor Jonathan Olsen: Well, there has been some great work looking at the relationship between the AfD and the Greens. I think the Technical University of Dresden has written a couple of pieces on this. I remember one article that essentially discusses the AfD as the “anti-Greens.” They position themselves as such because they take very distinct, opposing positions from the Greens and view them as their biggest enemy—not necessarily in terms of electoral strength, but certainly in terms of policies and ideology. The image of the Greens and the image of the AfD are diametrically opposed, and the AfD very much positions itself in direct opposition to them.

Issues like sustainability and environmental protection are, again, wrapped within a German nationalist framework. Their rhetoric suggests that, of course, they want environmental sustainability and to protect the environment, as it is part of the natural basis of life and the German homeland. The argument follows that those who love their homeland will naturally want to protect its environment.

This framing allows the AfD to present some environmental policies—such as reducing the use of pesticides or other forms of environmental protection—as being in line with their nationalist agenda. However, where they truly differentiate themselves and cast themselves as the “anti-Greens” is in their opposition to climate protection and alternative energies, particularly as part of a broader climate policy.